Abstract

ATRX belongs to the family of SWI2/SNF2-like ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling molecular motor proteins. Mutations of the human ATRX gene result in a severe genetic disorder termed X-linked α-thalassemia mental retardation (ATR-X) syndrome. Here we perform biochemical and genetic analyses of the Drosophila melanogaster ortholog of ATRX. The loss of function allele of the Drosophila ATRX/XNP gene is semilethal. Drosophila ATRX is expressed throughout development in two isoforms, p185 and p125. ATRX185 and ATRX125 form distinct multisubunit complexes in fly embryo. The ATRX185 complex comprises p185 and heterochromatin protein HP1a. Consistently, ATRX185 but not ATRX125 is highly concentrated in pericentric beta-heterochromatin of the X chromosome in larval cells. HP1a strongly stimulates biochemical activities of ATRX185 in vitro. Conversely, ATRX185 is required for HP1a deposition in pericentric beta-heterochromatin of the X chromosome. The loss of function allele of the ATRX/XNP gene and mutant allele that does not express p185 are strong suppressors of position effect variegation. These results provide evidence for essential biological functions of Drosophila ATRX in vivo and establish ATRX as a major determinant of pericentric beta-heterochromatin identity.

Keywords: Chromatin/Regulation, Chromatin/Remodeling, Chromatin/Epigenetics, Chromosomes/Centromeres, Chromosomes/Chromatin Structure, Chromosomes/Nucleosome, Gene/Regulation, Genetics/Drosophila

Introduction

Eukaryotic nuclear DNA is compacted into a nucleoprotein complex referred to as chromatin (1). The basic repeating unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, consists of 146 bp of DNA wrapped in 1.7 left-handed superhelical turns around the core histone octamer (2). Different organization levels of chromatin range from 10- and 30-nm filaments in dispersed interphase chromatin to higher order structures in specialized chromosome domains such as telomeres and centromeres to the highly condensed mitotic chromatin fiber. Chromatin is a vastly dynamic entity that varies in structure throughout development and cell cycle progression. Importantly, chromatin is the natural substrate for essential nuclear reactions such as DNA replication recombination, repair, and transcription. The packaging of DNA into various forms of chromatin provides the cell with the means to compact and to store its genetic material and creates an additional level of regulation of the nuclear DNA metabolism.

Unlike transcriptionally active, gene-rich, early replicating euchromatin in metazoan chromosome arms, heterochromatin is usually associated with the repression of genetic activity and other enzymatic processes in the nucleus and shelters specialized regions of chromosomes such as centromeres and telomeres (3, 4). Heterochromatin protein HP1a is the major component and diagnostic marker of heterochromatin. In Drosophila polytene chromosomes, HP1a is normally highly concentrated in and near the chromocenter and also associated with telomeres, the fourth chromosome, and a few euchromatic loci (5). Position effect variegation (PEV)2 is observed when expression of a gene is repressed in a stochastic manner by alteration of its native genomic location, usually by positioning within or near large blocks of heterochromatin. Many gene mutations that are known to suppress PEV affect protein factors that are involved in the establishment and maintenance of heterochromatin (6–8). For instance, one such dominant suppressor gene, Su(var)2-5, encodes Drosophila HP1a. HP1a deposition into chromosomes and the establishment of heterochromatin identity are presumed to be epigenetically regulated in a complicated fashion and depend on core histone and DNA modification enzymes, linker histones, boundary elements, retrotransposon activity, repetitive DNA transcription, and the RNA interference machinery (9–13).

Pericentric heterochromatin in Drosophila has conventionally been distinguished as a “more static” alpha-heterochromatin, which embeds AT-rich satellite DNA and other repetitive sequences of the centromeres and proximal pericentric regions, and a “more dynamic” beta-heterochromatin (14). Whereas alpha-heterochromatin is transcriptionally inert, beta-heterochromatin harbors a large number of genes (with a density comparable with that of euchromatin) and active retrotransposon elements. It also undergoes polytenization due to substantial endoreplication in larval cells. Importantly, most genetic assays for heterochromatic silencing (such as PEV) are directed toward beta-heterochromatin, as insertion sites and breakpoints of variegated alleles map to locations within beta-heterochromatin.

Chromatin remodeling complexes are characterized by the presence of an ATPase subunit from the SNF2-like family of the DEAD/H (SF2) superfamily of DNA-stimulated ATPases (15, 16). For example, the prototype chromatin remodeling factor, yeast SWI/SNF, is a multisubunit complex that contains the ATPase SWI2/SNF2 and 11 other polypeptides (17). The term “remodeling of chromatin” is currently vaguely used to describe a variety of molecular activities that result in regulation of a range of nuclear functions. The older simplistic concept assumes the role of chromatin remodeling as merely a counterbalance to the general repressive nature of chromatin. According to that concept, a variety of chromatin-remodeling factors use ATP hydrolysis solely to facilitate access to DNA for the enzymes of DNA metabolism. Recent evidence suggests that despite biochemical similarities, different chromatin remodeling factors can have radically dissimilar biological functions (18). Remodeling factors themselves can mediate DNA metabolism (e.g. homologous recombination by Rad54 (19)) or have unique functions in chromatin metabolism (e.g. histone deacetylation by Mi2/NURD (20) and nucleosome assembly by ACF, RSF, and CHD1 (21)).

X-linked α-thalassemia mental retardation (ATR-X) syndrome is a rare developmental disorder in males characterized by severe developmental delay, facial dysmorphism, urogenital abnormalities, and α-thalassemia (22, 23). The syndrome is X-linked-recessive and results from mutations of a widely expressed SNF2-like ATPase, ATRX (24). ATRX localizes predominantly to pericentric loci in mammalian cells (25). In addition, ATRX was observed to physically interact with heterochromatin protein HP1, histone methyltransferase EZH2, and a transcriptional cofactor, Daxx (26–28).

ATRX mutations in patients cause diverse abnormalities in gene regulation. For instance, a subset of ATR-X patients exhibit perturbation in α-globin expression (22). Also, the degree of DNA methylation in rDNA arrays of human patients is significantly reduced (29). In mouse knock-out models, ATRX absence is lethal during early embryogenesis (30). In conditional knock-out in the forebrain, a wide-spread apoptosis during differentiation of the cortical neurons is observed (31). Clinical manifestations of the ATR-X syndrome are extremely variable. There is a wide spectrum of severity of handicap phenotypes (22, 32). For instance, related patients may exhibit marked variation in intellectual quotient (33). It is unclear how this phenotypic diversity is established. One possibility is that regulation of gene expression by ATRX is achieved through epigenetic mechanisms. This hypothesis is further supported by the observed role of ATRX in regulation of DNA (and, possibly, histone) modifications.

Despite significant effort, understanding of the molecular basis of ATR-X remains limited. Efforts to understand the biological function of mammalian ATRX have been hampered by the lack of efficient genetic techniques to assay gene activity and chromatin states in vivo. There are also no convenient biochemical sources for purification of the native protein complex. Drosophila protein ATRX/XNP is the fly ortholog of ATRX. The human and fly proteins are functionally related according to phylogenetic analysis, their physical association with HP1 and localization pattern in the nucleus. Recently, ectopic overexpression of Drosophila ATRX was found to induce neuronal apoptosis via JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and dFOXO pathways (34, 35). The function of ATRX/XNP was correlated with that of HP1a by observations of physical interactions of recombinant polypeptides in glutathione S-transferase pulldown experiments and dominant PEV suppression by deficiencies that uncover the ATRX/XNP gene, xnp/atrx (36).

Here we have begun to study the function of Drosophila ATRX by methods of protein biochemistry and fly genetics. We discovered that ATRX/XNP forms a stable complex with HP1a and that HP1a can stimulate biochemical activities of ATRX in vitro. Loss-of-function mutations of the fly ATRX gene significantly affect fly viability. xnp/atrx is a strong suppressor of PEV. Furthermore, the mutations of the gene result in reduced deposition of HP1a in pericentric X beta-heterochromatin of larval salivary gland cells. Thus, ATRX plays an important role in heterochromatin function and establishment of its biochemical identity in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Baculovirus Expression Constructs and Recombinant Protein Synthesis and Purification

cDNA fragments that encompass the complete coding sequences of Drosophila ATRX/XNP (EST LD28477) and HP1a (EST LD10408) were cloned into pFastBac1 (Invitrogen) to express untagged ATRX, FLAG-ATRX, ATRX-FLAG, untagged HP1a, and FLAG-HP1a. Specific details of preparation of the constructs are available upon request. Recombinant ATRX polypeptide or its complex with HP1a were expressed in Sf9 cells and purified by FLAG immunoaffinity chromatography as described previously (37).

Antibodies to Drosophila ATRX and Western Blot Analyses

cDNA fragment of Drosophila ATRX corresponding to amino acid residues 1118–1311 (C terminus) was cloned in-frame with a C-terminal His6 tag into pET-29a (Novagen). The antigen was expressed in bacteria and purified in 6 m urea on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen). The antigen was used to immunize rabbits (Rabbit Pocono Laboratory and Farm) and to prepare affinity purification resin by cross-linking to Aminolink Plus Coupling Gel (Pierce). IgG fraction was purified from anti-ATRX antiserum on Bakerbond ABX Plus (Mallinckrodt Baker), and specific antibodies were further purified on the affinity column by low pH elution according to the manufacturer's manual (Pierce). The antibodies were used for Western blots at 1:5000 dilution. For HP1a westerns, C1A9 mouse monoclonal antibodies (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) were used at a 1:2000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used at 1:5000. A chemiluminescent signal of the enzymatic activity of horseradish peroxidase was visualized with Immobilon Western substrate (Millipore) as described by the manufacturer.

For developmental expression analyses, whole-organism lysates were prepared by resuspension of wild-type animals at the appropriate stage in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and boiling. Total protein concentrations were measured by in-gel Coomassie staining of gels. ∼15 μg of total protein per lane was loaded for Western blots.

Purification of the Native Form of ATRX from Drosophila Embryos

The native form of ATRX p185 was purified to homogeneity from embryonic nuclear extracts. Drosophila embryos were collected 0–12 h after egg deposition. The nuclear extract was prepared as previously described (38). The extract (400 g of embryos) was applied to a P11 phosphocellulose (Whatman) column (120 ml) equilibrated in 0.1 m NaCl HEG buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.01% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mm glycerophosphate, 0.5 mm benzamidine). The 0.1 m NaCl wash was followed by a linear gradient from 0.1 to 1 m NaCl in HEG. Fractions from this and later steps were analyzed for the presence of ATRX/XNP by Western blot. The ATRX peak fractions were precipitated with ammonium sulfate (50% saturated) and dialyzed against HEG until the conductivity of sample was equivalent to that of HEG + 0.1 m NaCl. The dialyzed sample was applied to a Source 15Q (GE Healthcare) column (12 ml), and the protein was eluted by a linear gradient from 0.1 to 1 m NaCl in HEG. ATRX-containing fractions were dialyzed against 0.1 m NaCl in HEG and applied to a Source 15S (GE Healthcare) resin (1 ml). The protein was eluted by a linear gradient from 0.1 to 1 m NaCl in HEG. ATRX-containing fractions were applied to a Superose 6 (GE Healthcare) column (125 ml, 1.6 × 62.2 cm) equilibrated with 0.15 m NaCl in HEMG (HEG + 12.5 mm MgCl2).

ATRX immunoaffinity resin was prepared by cross-linking Bakerbond-purified anti-ATRX IgG (see above) to Aminolink Plus Coupling Gel (Pierce). Approximately 2.5 mg of total protein was cross-linked to 1 ml of the resin. The ATRX p185 peak fraction from the size exclusion column (approximate molecular mass of 200 kDa) was applied to the ATRX immunoaffinity column (1 ml) in HEG + 0.1 m NaCl, and after extensive washing (4 × 5 ml) the protein was eluted by 2.5 m glycine-HCl, pH 2.0, and neutralized with Tris base. The proteins in the eluate were resolved on SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver and Coomassie staining, and prominent protein bands were submitted for mass spectrometry sequencing.

Restriction Enzyme Accessibility (REA) Assay

Oligonucleosome (chromatin) templates were reconstituted from native Drosophila core histones by salt dialysis on ∼3-kbp pGIE-0 plasmid (39). Recombinant FLAG-ISWI was prepared as described previously (37). REA assays were carried out as described previously (19). The reactions (total volume, 20 μl) contained the indicated factors and the restriction enzyme HaeIII (15 units, New England Biolabs) in the buffered reaction medium (25 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.5, 10 mm magnesium acetate, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 3 mm ATP, 30 mm phosphocreatine, 2 units/ml creatine phosphokinase). The final concentrations of the components were as follows: chromatin (equivalent to 400 ng of plasmid DNA, 10 nm); ISWI, ATRX p185, 16, 50, and 150 nm, respectively: HP1a, 32, 100, and 300 nm. The reactions were incubated at 27 °C for 1 h. The DNA samples were deproteinized and subjected to electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. The DNA was visualized by staining with ethidium bromide.

ATPase Assay

The ATPase activity of ATRX and ISWI was measured by thin-layer chromatography of [γ-32P]ATP hydrolysis products as described previously (40). The reactions (total volume 25 μl) contained 50 nm chromatin remodeling factors, 0 or 100 nm HP1a, 200 μm total ATP with the phosphocreatine ATP regeneration system in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 0.2 m NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.02% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. Where indicated, the reactions also contained 260 ng of pGIE-0 (5 nm) or equivalent amount of salt-dialyzed chromatin (100 nm nucleosomes). Recombinant HP1a did not have detectable ATPase activity (not shown).

Stocks and Drosophila Culture

Flies were grown, and crosses were performed at 25 °C on standard cornmeal/molasses media with dry yeast added to the surface. Unless stated otherwise, the mutations and chromosomes used are described in FlyBase. Stock 39C-5 carries a variegating hsp70-mini-w insertion into 2L subtelomeric repeat (41). The variegating line KV161 (42, 43) contains an insertion of P{SUPor-P} element into the h42-h43 region of the second chromosome heterochromatin. DX1 is a variegating insertion line that contains six tandem copies of P{lacW} at 50C cytogenetic region (second chromosome), with one inverted copy in the array (44).

xnp/atrx Alleles

Deletion alleles were generated by imprecise excision of a P{EP} element (P{EP}xnp[EP635]) inserted in the 5′-untranslated region of the xnp locus. P-element excisions were performed by mating homozygous P{EP}xnp[EP635] females with males carrying the source of transposase, P{Δ2-3}99B. Individual w; P{EP}xnp[EP635]/P{Δ2-3}99B males were then crossed with yw;TM3, Sb/TM6B, Tb females to select for excision events (w−). Individual w− male progeny from the latter cross were back-crossed to yw; TM3, Sb/TM6B, Tb females to establish excision lines. A total of 653 excision lines were analyzed by PCR across the xnp locus, and 5 xnp/atrx imprecise excision alleles were obtained. Sequences of PCR primer pairs are available upon request. The deleted fragments of the xnp locus are as follows: xnp[5], 21,306,126 to 21,308,530; xnp[6], 21,307,736 to 21,308,530; xnp[7], 21,306,955 to 21,308,530; xnp[8], 21,306,938 to 21,308,567; xnp[9], 21,306,897 to 21,308,530 (FlyBase Annotation, Release 5.19).

Viability of xnp/atrx Alleles

The original P{EP}xnp[EP635] insertion was outcrossed in six generations into wild-type w[1118] background. 10 w+ females and 5 w− males were used in each cross. The xnp[5] and xnp[6] deletion alleles were then outcrossed into the w[1118]; EP635 background in six generations. 10 w− females and 5 w+ males were used in each cross. The resulting outcrossed xnp[5]/EP635 and xnp[6]/EP635 alleles were mated inter se, and the progeny (homozygotes versus heterozygotes) were scored by eye color phenotype (Table 1). Comparable results were obtained when xnp alleles were crossed to the Df(3R)Exel6202 deficiency, which uncovers xnp/atrx (not shown).

TABLE 1.

Viability of xnp/atrx alleles

Heterozygotes of P{EP(3)}635 and the indicated alleles of xnp/atrx were crossed inter se, and the adult progeny were scored based on the eye color phenotype. The numbers represent the total numbers of eclosed adults with the indicated eye phenotypes. The expected (Mendelian) numbers based on the total number of progeny are shown in parentheses.

| Parents | Progeny |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| EP635/EP635 | w−/EP635 | w−/w− | |

| +/EP635 | 55 (56) | 115 (113) | 55 (56) |

| xnp[5]/EP635 | 66 (51) | 103 (105) | 10 (51) a |

| xnp[6]/EP635 | 53 (52) | 99 (102) | 51 (52) |

a Statistically significant effect on viability of xnp[5] homozygotes (p = 3 × 10−7). xnp[5] allele is semilethal.

The Effect of xnp/atrx Mutations on PEV

The xnp alleles were tested for their effect on expression of w and y reporter genes in various insertions and chromosome rearrangements. The following stocks were used: w[m4h]; TM3, Sb/TM6B, Tb (PEV in the X chromosome rearrangement); yw[67c23]; KV161; TM3, Sb/TM6B, Tb (PEV in the insertion into pericentric heterochromatin of the second chromosome); w[1118]; 39C-5; sens[Ly]/TM6B, Tb (telomeric position effect), w[1118]; DX1/CyO; sens[Ly]/TM6B, Tb (variegated expression of repeated transgenes). Females homozygous for xnp mutations were crossed to males carrying variegating reporters. In some cases, reciprocal crosses were performed to assay for possible maternal effects. To study the recessive effects of xnp mutations, we crossed xnp/TM6B males carrying the corresponding reporter to xnp homozygous females. We used an internal control in each cross of a mutant to a reporter; to assay for dominant modification of w expression we compared progeny with the mutation and their nonmutant siblings from the same vial. As an external control we used the same crosses with the stock carrying a precise excision of P{EP}xnp[EP635] element. All crosses with any particular reporter were performed simultaneously on the same food using females from the same virgin collections. Flies were collected in 1-day intervals, and progeny of different genotypes were compared directly using side-by-side visual analysis. Parents were transferred to a fresh vial every 2 days to prevent overcrowding. Before the analysis of mutation effects, we estimated the effect of all balancer and dominantly marked chromosomes on all reporters. The TM6, Tb balancer chromosome was not found to substantially affect the silencing of the reporter genes.

Polytene Chromosome Analyses

Antibody staining of polytene chromosomes was performed essentially as described (45). Salivary glands were dissected in PBS, pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100 solution, incubated for 30 s in 3.7% formaldehyde solution (3.7% formaldehyde, 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, pH 7.5). Fixed tissues were then transferred to 3.7% formaldehyde, 50% acetic acid for 2 min 45 s, and the glands were squashed. Slides were frozen in liquid nitrogen and immersed in PBS. After washing 2 times in PBS for 15 min, the slides were incubated with blocking solution (3% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 0.2% Tween 20, and 10% nonfat dry milk in PBS) for 1 h. Primary antibody was diluted in blocking solution and added to the slide. Affinity-purified rabbit anti-ATRX antibody was diluted 1:200, and monoclonal anti-HP1a antibody (C1A9) was used at a 1:4 dilution. Overnight incubation in a humid chamber at 4 °C followed. Slides were rinsed 3 times with PBS and washed for 15 min in solution A (300 mm NaCl, 0.2% (w/v) Tween 20, and 0.2% (w/v) Nonidet P-40 in PBS) and then for 15 min in solution B (400 mm NaCl, 0.2% (w/v) Tween 20, 0.2% (w/v) Nonidet P-40 in PBS). After rinsing 2 times with PBS, the secondary antibody was added. Secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit Alexafluor 488, anti-mouse Alexafluor 594, Invitrogen) were diluted 1:200 in blocking solution containing 2% normal serum and incubated with the slides for 40 min at room temperature. The slides were washed exactly as described for the primary antibody incubation. After staining for 10 min in 0.5 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution in PBS and washing for 10 min in PBS, Vectashield (Vector) was added before a coverslip was mounted to prevent bleaching.

RESULTS

Drosophila ATRX/XNP Is Expressed as Two Polypeptides, p185 and p125

To analyze the expression of Drosophila ATRX in vivo, we raised polyclonal antibodies against the C terminus of ATRX/XNP (amino acid residues 1118–1311). In Western blots of embryonic (0–12 h) nuclear extracts, the antibodies recognize two polypeptide bands of ∼185 and 125 kDa (Fig. 1A). The atrx/xnp gene is expressed as a single unique mRNA, and the two protein isoforms (referred to as ATRX185 and ATRX125) arise as a result of alternative utilization of translation initiation methionine codons, Met-1 and Met-266 (36).

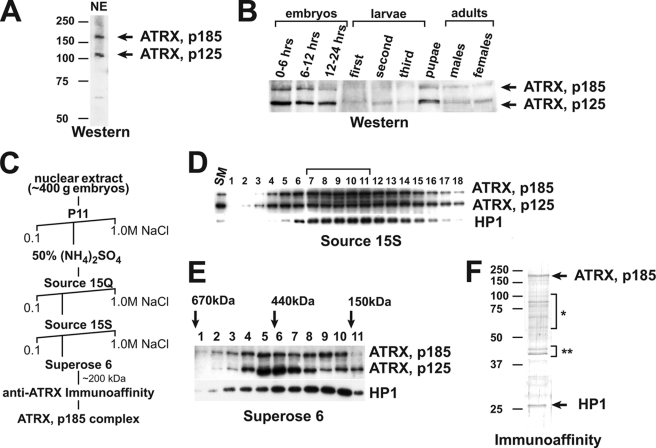

FIGURE 1.

Purification of the native form of ATRX/XNP. A, Western blot analysis of Drosophila nuclear extract (NE) is shown. Antibodies against a C-terminal epitope of Drosophila ATRX recognize two polypeptide bands with apparent molecular masses of 185 and 125 kDa (arrows). B, developmental analysis of ATRX/XNP expression is shown. Whole-animal lysates of various developmental stages of Drosophila were analyzed by a Western blot with anti-ATRX antibodies. Uniformity of the total protein loading was controlled by Coomassie staining of similarly loaded SDS-PAGE gels (not shown). C, shown is a chromatographic scheme for purification of the native form of ATRX185 from Drosophila embryos. D, source 15S chromatography is shown. The peak ATRX (p185 and p125) fractions from the Source 15Q step were applied to the Source 15S column. The column fractions were analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against Drosophila ATRX and HP1a. ATRX/XNP and HP1a co-fractionate with a peak in fractions 7–11 (bracket, of a total of 45 gradient fractions). E, size-exclusion chromatography is shown. The peak fractions from the Source 15S step were applied to the Superose 6 column, and the column fractions were analyzed by Western blot. Approximate molecular masses of the native proteins were estimated based on the peaks of fractionation of molecular mass markers (arrows). ATRX125 fractionates with a peak in fractions 5–7 (estimated molecular mass, ∼500 kDa), whereas p185 fractionates with two approximately equivalently abundant peaks in fractions 5–7 and 8–10 (estimated molecular mass, ∼200 kDa). HP1a co-fractionates with the second peak of p185. F, the native ATRX185 complex comprises ATRX185 and HP1a. The second peak (fraction 9) of ATRX185 from Superose 6 step (∼200 kDa) was applied to the anti-ATRX immunoaffinity column, and the protein was eluted with a low pH buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. The identities of the protein bands were determined by mass spectometry sequencing (arrows and brackets). Brackets: *, proteolysis products of ATRX/XNP; **, yolk proteins.

We analyzed the developmental expression pattern of ATRX/XNP and discovered that both protein isoforms are expressed throughout development, from embryo to adult, although the expression is particularly high in embryos and pupae (Fig. 1B).

ATRX185 and ATRX125 Form at Least Two Distinct Complexes in Drosophila Embryos

To isolate the native form of Drosophila ATRX, we prepared nuclear extracts from embryos 0–12 h after egg deposition and fractionated them by conventional chromatography (Fig. 1C). The fractions were selected based on ATRX/XNP protein abundance in Western blots. ATRX185 and ATRX125 co-fractionated in several chromatographic steps, including phosphocellulose P11 and cation and anion exchange media (Fig. 1D). However, size exclusion chromatography allowed partial resolution of p185 and p125 (Fig. 1E). Whereas both p185 and p125 could be found in complexes of the approximate molecular mass of 500 kDa, a substantial portion of p185 separated in an additional, unique chromatographic peak that fractionated with a predicted molecular mass of ∼200 kDa. Thus, Drosophila ATRX forms at least two distinct complexes in vivo.

The Native Form of Drosophila ATRX/XNP p185 Comprises ATRX185 and HP1a

To purify the native form of ATRX185 to apparent homogeneity, we prepared ATRX immunoaffinity resin by cross-linking purified IgG from ATRX-specific antisera to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose. We then applied the gel filtration fraction 9 (Fig. 1E) from the second peak of ATRX185 (∼200 kDa) to the immunoaffinity column and eluted the bound material with a low pH buffer. The purified complex contained two full-length polypeptides, ATRX185 and heterochromatin protein HP1a (Fig. 1F). To confirm that HP1a is a specific component of the complex, we analyzed earlier chromatographic fractions (Fig. 1C) by Western blotting with antibodies against HP1a and discovered that HP1a precisely co-fractionates with ATRX185 in multiple chromatographic steps (Figs. 1, D and E, and data not shown). Thus, one of the native complexes of ATRX/XNP in Drosophila embryos comprises ATRX185 and HP1a.

Recombinant Drosophila ATRX Purifies in a Stable Complex with HP1a

To purify the complex of ATRX/XNP with HP1a in a recombinant form and to analyze its biochemical properties, we prepared baculoviruses that express full-length ATRX/XNP protein (untagged and N- and C-terminal FLAG-tagged) or HP1a (untagged or N-terminal FLAG-tagged). When C-terminal-tagged ATRX/XNP is expressed in Sf9 cells, both p185 and p125 isoforms are purified by FLAG chromatography. However, only ATRX185 is purified when the polypeptide is tagged on the N terminus (Fig. 2A, left panel). ATRX125 is presumably lost during purification, because it is translated from the internal Met-266 codon and does not include the FLAG tag.

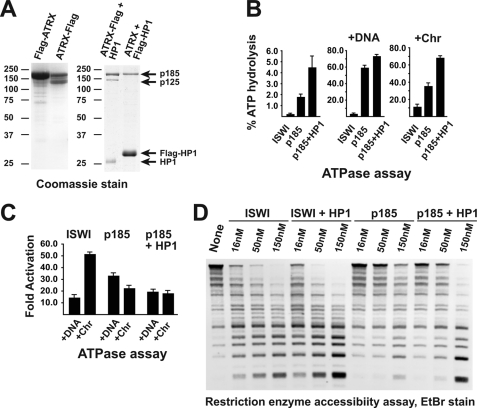

FIGURE 2.

Drosophila ATRX185 physically and functionally interacts with HP1a. A, ATRX185 specifically binds HP1a. N-terminal or C-terminal FLAG-tagged Drosophila ATRX proteins were expressed alone (left panel) or in combination with Drosophila HP1a protein (wild-type or N-terminal FLAG-tagged) in Sf9 cells using baculovirus expression system. The protein complexes were purified by FLAG affinity chromatography. The complex purified through FLAG-HP1a does not contain untagged ATRX125 (right panel, right lane). ATRX185 appears substoichiometric due to more efficient expression of FLAG-HP1a. The positions and sizes (kDa) of molecular mass markers are indicated on the left of the panels. B, ATPase activities of recombinant Drosophila ISWI, ATRX185, and ATRX185·HP1a complex are shown. The indicated proteins (∼1.3 pmol) were analyzed in ATPase reactions in the absence or presence of 260 ng (∼0.13 pmol) of plasmid DNA or equimolar amounts of reconstituted oligonucleosomes (∼2.6 pmol of nucleosomes; Chr). All reactions were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent S.D. C, DNA and nucleosomes stimulate the ATPase activity of ATRX. The indicated proteins were analyzed in ATPase assay reactions in the presence of DNA or oligonucleosomes as in B. D, stimulation of nucleosomal array remodeling activity of Drosophila ATRX by HP1a is shown. Chromatin template (∼0.2 pmol and ∼4 pmol of nucleosomes) was digested with HaeIII in the absence or presence increasing amounts (∼0.3, ∼1, ∼3 pmol) of the indicated remodeling enzymes. Where indicated, double equimolar amounts of HP1a were added to the reactions. Deproteinated DNA fragments were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. Recombinant HP1a alone does not possess appreciable nucleosome remodeling activity (not shown).

When C-terminal FLAG-tagged ATRX/XNP is co-expressed with untagged HP1a, all three polypeptides co-purify by FLAG chromatography. On the other hand, when untagged ATRX/XNP is co-expressed with FLAG-tagged HP1a, HP1a co-purifies only with the p185 isoform (Fig. 2A, right panel). This result is consistent with physical interactions between HP1a and an CXVXL motif in the N terminus of p185 that were previously observed in glutathione S-transferase pulldown experiments (36).

To confirm that recombinant ATRX185 and HP1a form a stable complex, we further purified it by conventional chromatography. ATRX/XNP and HP1a co-fractionate precisely on anion exchange resin (supplemental Fig. 1A). In size-exclusion chromatography, ATRX185 and HP1a co-elute in a protein peak with an approximate molecular mass of 200 kDa (supplemental Fig. 1B), consistent with the elution profile of the native ATRX185·HP1a complex (Fig. 1E). Finally, we co-expressed in baculovirus untagged ATRX/XNP, HP1a, and FLAG-tagged HP1a. Both forms of HP1a and ATRX185 were co-purified by FLAG chromatography. Furthermore, the three polypeptides remained associated with each other when subjected to size-exclusion chromatography (supplemental Fig. 1C). Thus, the stable complex of ATRX185 and HP1a contains at least 2 protomers of HP1a.

HP1a Stimulates Biochemical Activities of ATRX185

We then assayed the biochemical activities of various preparations of recombinant ATRX and ATRX·HP1a complexes. For these experiments we individually expressed and purified ATRX185 and HP1a polypeptides and mixed them (in a ∼1:2 molecular ratio) in assay reactions. In addition, we co-expressed and co-purified complexes of ATRX/XNP and HP1a, and identical results were observed (not shown).

First, we analyzed the ATPase activity of ATRX/XNP. Drosophila ATRX has a very strong basal ATPase activity. In the absence of DNA or nucleosomes, the rate of ATP hydrolysis by ATRX is ∼10-fold higher than that by another SNF2-like ATPase, ISWI (Fig. 2B). This rate is further stimulated (>2-fold) by the addition of HP1a. Interestingly, whereas ATPase activity of ISWI is strongly stimulated by the addition of both DNA and nucleosomes, the ATPase activity of ATRX is responsive to DNA, but no additional stimulation is observed when DNA is replaced by a chromatin template (Fig. 2C). In fact, in the absence of HP1a, ATRX/XNP may be mildly inhibited by the presence of nucleosomes.

The ATPase activity of ATRX185·HP1a complex is stronger than that of the individual ATRX185 polypeptide (Fig. 2B) but is less responsive to activation by DNA (Fig. 2C). It is possible that the recombinant HP1a associates with nucleic acids, which in turn stimulate enzymatic activities of ATRX185. To exclude this possibility, we analyzed HP1a preparations for the presence of contaminating nucleic acids. Recombinant HP1a does not contain detectable amounts of nucleic acids (supplemental Fig. 2A). When ATPase reactions with ATRX185 were supplemented with DNA at about one-thousandth of the typical (as in Fig. 2C) concentrations, we did not observe stimulation of the ATPase activity (supplemental Fig. 2B). Notably, HP1a that contains much less nucleic acids (supplemental Fig. 2A) could stimulate the activity of ATRX185 in the same conditions. Thus, HP1a has an intrinsic ability to interact with and stimulate the ATPase activity of ATRX185 polypeptide.

We then assayed the nucleosome remodeling activity of ATRX/XNP in REA assay. In the absence of HP1a, recombinant Drosophila ATRX does not efficiently remodel nucleosome templates (Fig. 2D). Although ATRX185 has an ATPase activity that is comparable with or higher than that of ISWI (Fig. 2B, right panel), its remodeling activity may be about 10-fold lower (compare ISWI, 16 nm and p185, 150 nm lanes, Fig. 2D). Similar results were observed in buffers of various ionic strengths and pH (not shown). On the other hand, the addition of HP1a to the reaction substantially stimulates the remodeling activity of p185. Although HP1a also somewhat stimulates the remodeling activity of ISWI, it has the most dramatic effect on ATRX/XNP; in the presence of HP1a, the ability of ATRX/XNP to remodel nucleosomes becomes comparable with that of ISWI (compare ISWI+HP1, 150 nm and p185+HP1, 150 nm lanes). Importantly, recombinant HP1a alone does not affect restriction enzyme accessibility of the template (not shown).

Mutations of atrx/xnp Affect Fly Viability

To analyze the function of Drosophila ATRX/XNP in vivo, we generated mutant alleles of xnp/atrx. The gene coding for ATRX/XNP is localized in the right arm of the third chromosome (3R, cytological region 96E1–96E2). We generated deletion alleles by imprecise excision of a P-element inserted in the 5′-end of xnp/atrx (Fig. 3A). Several excision events resulted in deficiencies that deleted various fragments of the 5′-untranslated region and coding regions of the gene as evidenced by PCR analyses of their genomic DNA. All these alleles were viable and fertile. Therefore, we collected embryos from inter se crosses of homozygous mutant parents and examined the expression of ATRX/XNP. All mutant animals expressed truncated versions of the protein (Fig. 3B) at various levels. On the other hand, one allele (xnp[5]) expressed the protein fragment with no functional ATPase domain. Thus, xnp[5] expresses a biochemically inactive ATRX polypeptide and is a loss-of-function allele of the gene. Also, xnp[6] eliminates the first of the two utilized in vivo translation initiation codons and only expresses the ATRX125 isoform of the protein.

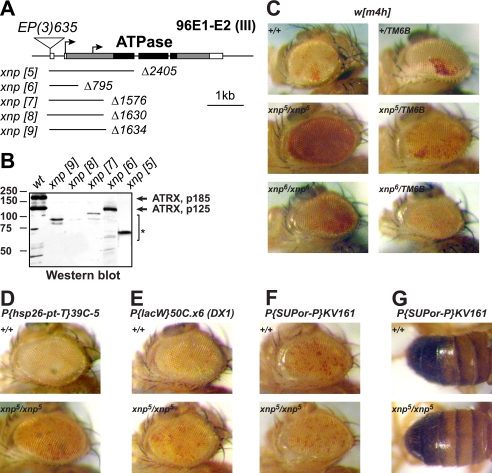

FIGURE 3.

Mutations of xnp/atrx suppress heterochromatic silencing. A, Drosophila ATRX genomic region and xnp/atrx imprecise excision alleles are shown. ATRX/XNP introns are represented by solid lines, and exons are represented by rectangles. The coding sequence is shaded, and its portion that codes for the ATPase domain is painted black. Arrows indicate alternative translation start methionine codons of the native ATRX/XNP. Solid lines under the gene schematic indicate the extent and breakpoints of the xnp deficiency alleles. Triangle, the insertion site of P{EP}xnp[EP635]; scale bar, 1 kbp. B, shown is Western analysis of xnp/atrx alleles. Wild-type (wt) or homozygous mutant embryos of indicated alleles were used to prepare protein lysates and analyzed on a Western blot with anti-ATRX/XNP antibody. The positions of native Drosophila ATRX polypeptides are indicated by arrows. The molecular masses of markers are shown in kDa on the left of the panel. *, truncated polypeptide products of the gene that are recognized by the C-terminal specific antibody. C–G, shown is the effect of xnp/atrx mutations on variegation of heterochromatin-silenced genes. xnp/atrx suppresses PEV in pericentric X chromatin of the In(1)w[m4h] rearrangement (C). It also suppresses silencing of the transgene insertion 39C-5 in 2L subtelomeric region (D) and tandem array of transgenes DX1 in 2R euchromatin (E). However, it does not suppress PEV in pericentric insertion KV161 on the second chromosome (F and G). Alleles and crosses are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Variegated expression of w (C–F) or y (G) transgenes was assayed.

Genomic deficiency Df(3R)Exel6202 uncovers several dozens of genes in 3R, including xnp/atrx. When xnp heterozygous mutant parents were crossed to heterozygous Df(3R)Exel6202 counterparts, we observed reduced numbers of xnp/Df adult progeny (not shown). The xnp[5] allele had the strongest effect on viability. To further examine how xnp/atrx mutations affect fly viability, we first outcrossed the EP(3)635 P-element insertion into the wild-type (w[1118]) background. We then outcrossed the imprecise excision alleles into w[1118]; EP635 background and determined the viability of homozygotes in inter se crosses of heterozygous mutant parents. We discovered that the loss-of-function mutation of xnp/atrx significantly affects fly viability; the viability of xnp[5] adults in these crosses was 20% that expected. Thus, xnp[5] is semilethal (Table 1). On the other hand, xnp[6] allele exhibits wild-type viability in these crosses. Therefore, although the N terminus of p185 is required for interactions with HP1a, it appears dispensable for the biological functions of ATRX/XNP that control fly viability.

atrx/xnp Suppresses Position Effect Variegation

Because ATRX185 forms a complex with heterochromatin component HP1a in vivo, we decided to test whether ATRX185 affects heterochromatin function in Drosophila, specifically heterochromatin-mediated silencing in PEV. To this end, we combined variegating w[m4h] allele, in which white is brought to close proximity to pericentric heterochromatin by rearrangement of the X chromosome, with xnp/atrx alleles. We discovered that all mutant alleles were strong recessive suppressors of white variegation (Fig. 3C and data not shown). In addition, xnp[5] had a weak dominant effect. This result is in contrast to observations that larger deficiencies that uncover xnp/atrx and adjacent genes are dominant suppressors of variegation (36).

Heterochromatin-mediated silencing is also observed when euchromatic genes are juxtaposed to telomeres or inserted in several copies in tandem repeats (46, 47). We hypothesized that ATRX/XNP may have a general role in transcriptional repression by heterochromatin. Consistently, we found ATRX/XNP to be also required for efficient silencing of telomeric insertions (Fig. 3D) and tandem arrays of transgenes (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, surprisingly, xnp/atrx mutations did not suppress variegation of white or yellow transgenes inserted in pericentric regions of the second or third chromosomes (Figs. 3, F and G, and data not shown).

Drosophila ATRX/XNP Is Enriched in Pericentric Beta-Heterochromatin of the X Chromosome

To further understand the biological function(s) of ATRX/XNP, we decided to study its localization pattern in Drosophila larval salivary gland polytene chromosomes by indirect immunofluorescence. Anti-ATRX/XNP antibodies brightly stain about 200 specific loci in euchromatic arms of the polytene chromosomes. Strikingly, the majority of the immunofluorescence signal is prominently concentrated close to the pericentric heterochromatin (Fig. 4A). Unlike the ectopically overexpressed transgene, which is ubiquitously distributed (36), the native protein is excluded from most euchromatic bands and interbands and does localize close to the chromocenter.

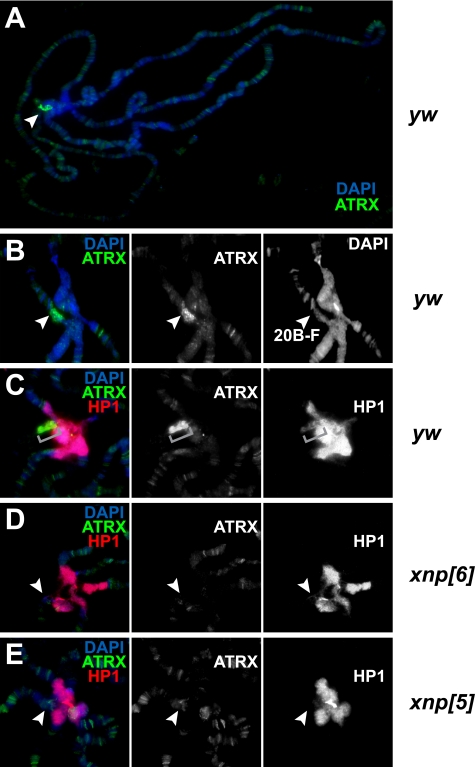

FIGURE 4.

Drosophila ATRX facilitates deposition of HP1a into pericentric beta-heterochromatin of the X chromosome. A, the majority of Drosophila ATRX localizes to a pericentric region of polytene chromosomes. Polytene chromosomes from salivary glands of wild-type (y w) L3 larvae were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue) and anti-XNP/ATRX antibodies (green). Drosophila ATRX localizes to multiple sites in euchromatic arms; however, the major signal is observed in the pericentric region (arrowhead). B, the major locus of ATRX staining in pericentric heterochromatin corresponds to beta-heterochromatin of the proximal X (cytogenetic region 20B-F, arrowheads). Polytene chromosomes were stained as in A. C, pericentric staining of ATRX/XNP co-localizes with weak HP1a staining of beta-heterochromatin. Red, HP1a. Brackets, 20B-F cytogenetic region. D, ATRX185 is specific to the X beta-heterochromatin and is required for HP1a loading in this region. Polytene chromosomes from salivary glands of atrx[6] L3 larvae were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue), anti-HP1a (red), and anti-ATRX/XNP (green) antibodies. In the xnp[6] allele, which does not express p185, ATRX/XNP and HP1a staining is missing in 20B-F region (arrowheads). E, the loss-of function mutation of xnp/atrx results in elimination of HP1a from pericentric beta-heterochromatin of X. Polytene chromosomes from salivary glands of xnp[5] L3 larvae were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue), anti-HP1a (red), and anti-ATRX/XNP (green) antibodies. ATRX and HP1a staining is missing in 20B-F region (arrowheads). Residual ATRX/XNP staining of the truncated protein is apparent in euchromatic regions.

Higher resolution imaging of anti-ATRX/XNP-stained polytene chromosomes reveals that the prominent pericentric immunofluorescence signal maps exclusively to the 20B-F region near pericentric X heterochromatin (Fig. 4B). This cytogenetic region represents a distal portion of beta-heterochromatin. The beta-heterochromatic signal of ATRX/XNP overlaps with weak HP1a staining (Fig. 4C). Importantly, very little or no ATRX is observed in the beta-heterochromatic regions of autosomes, consistent with the apparent lack of ATRX/XNP function in silencing of pericentric transgenes on the second and third chromosomes (Figs. 3, D and E).

Because ATRX185 but not ATRX125 forms a native complex with HP1a, we decided to test whether ATRX185 and/or ATRX125 is present in the 20B-F region of polytene chromosomes. To this end, we performed immunofluorescence staining of chromosomes from xnp[6] larvae that do not express ATRX185 (Fig. 3B). Remarkably, ATRX staining in X beta-heterochromatin is missing in xnp[6] animals (Fig. 4D). Thus, the ATRX/XNP signal in beta-heterochromatin of X represents the major localization site of the native ATRX185·HP1a complex in chromatin in vivo.

ATRX185 Is Required for HP1a Incorporation into Pericentric Beta-heterochromatin

When we stained polytene chromosomes of xnp[6] larvae with anti-HP1a antibodies, we discovered that the HP1a signal was missing (or drastically reduced below detection limit) in the 20B-F region. Similarly, the loss of function mutant allele xnp[5] exhibited a defect in HP1a loading in 20B-F (Fig. 4E). The residual euchromatic ATRX/XNP staining in xnp[5] polytene chromosomes is presumably observed due to residual expression of a biochemically inactive truncated ATRX/XNP (Fig. 3B). Thus, ATRX/XNP (and specifically, its ATRX185 isoform) is required for HP1a targeting to pericentric X beta-heterochromatin in vivo.

DISCUSSION

The Native Complexes of Drosophila ATRX

Mammalian and fly ATRX have previously been implicated in the function of heterochromatin, core histone modifications, regulation of DNA methylation, and interactions with heterochromatin protein HP1 (25, 26, 29). However, here we demonstrate for the first time that metazoan ATRX can form a stable complex with HP1a in vivo. Although HP1a is known to physically interact with various partners, including histones, histone and DNA modification enzymes, DNA replication and repair proteins, nuclear structure proteins, and transcription factors (48), to our knowledge this work is the first demonstration that HP1 exists in a stable complex with a nucleosome remodeling factor.

HP1a is known to homodimerize through interactions within its chromoshadow domain (5). Furthermore, at least two HP1a protomers are present in its complex with ATRX185 (supplemental Fig. 1C). Considering the predicted molecular mass of the complex (∼200 kDa) and the large molecular excess of HP1a relative to ATRX/XNP in vivo, it is likely that ATRX185 binds a dimer of HP1a, and this heterotrimer constitutes the predominant native form of ATRX185·HP1a complex.

HP1a apparently plays an important regulatory role in biochemical activities of XNP/ATRX. Interestingly, the basal ATPase activity of ATRX185 is somewhat inhibited in the absence of HP1a. Thus, HP1a may introduce a conformational change to the ATRX185 polypeptide that derepresses its enzymatic activity. HP1a also strongly stimulates the ability of ATRX185 to remodel nucleosomes in REA assay (Fig. 2). In fact, ATRX185 possesses extremely little nucleosome remodeling activity in the absence of HP1a. This strong stimulation cannot be attributed solely to the enhanced ATPase activity of the enzyme. Therefore, HP1a may also promote nucleosome remodeling by other mechanisms. For instance, it may facilitate ATRX tethering to nucleosomes. Alternatively, ATRX may conversely stimulate HP1a interactions with chromatin templates, which will manifest as increased nucleosome remodeling in the REA assay.

Importantly, the smaller isoform of ATRX/XNP (ATRX125) does not physically interact with HP1a and forms an alternative complex(es). In size-exclusion chromatography, recombinant ATRX125 is separated from the ATRX185·HP1a complex into a distinct peak with the molecular mass <150 kDa (supplemental Fig. 1B). This elution profile is unlike that of the native form of ATRX125, which fractionates in a peak with a predicted molecular mass of ∼500 kDa (Fig. 1E). Thus, the native ATRX125 likely forms a multisubunit complex with additional polypeptides that may be involved in regulation of biological functions of ATRX125 in vivo.

Loss-of-function mutation of ATRX/XNP gene is semilethal (Table 1). However, elimination of heterochromatin-specific ATRX185 isoform does not substantially affect fly viability. Therefore, ATRX125 has additional biological functions that do not depend on HP1a and are targeted toward euchromatic loci. For instance, the putative ATRX125 complex may play regulatory roles in transcription of certain euchromatic genes or regulate other chromatin functions.

The Role of ATRX/XNP in Heterochromatin Function and Deposition of HP1a

The xnp/atrx mutations are strong recessive suppressors of pericentric PEV in the X chromosome. They also have an effect on variegation of tandemly repeated transgene arrays and telomeric position effect (Fig. 3). The latter observation suggests that ATRX/XNP may have a function in heterochromatin silencing that is independent of HP1a, as Su(var)2-5 alleles have little or no dominant effect of silencing of the telomeric 39C-5 insertion (46). Alternatively, the dose reduction of HP1a in heterozygous alleles of Su(var)2-5 may have a disproportionally weaker influence on its presence in telomeres, which would not be detected by analyzing PEV. On the other hand, the complete elimination of functional ATRX185·HP1a complex in homozygous xnp/atrx alleles may have a stronger effect on HP1a availability for both telomeric and pericentric silencing. Notably, xnp[5] is a weak dominant suppressor of pericentric PEV. This effect is not due to an antimorphic effect of expression of the truncated form of ATRX/XNP (Fig. 3B), as this truncated product is not localized to the normal pericentric site of Drosophila ATRX (Fig. 4E).

In polytene chromosomes, ATRX185 specifically localizes to pericentric beta-heterochromatin of the X chromosome, where it overlaps with HP1a (Fig. 4). This localization is unlikely to be explained by interactions with HP1a, because ATRX is largely excluded from other loci, where HP1a is abundantly present (e.g. chromocenter). Therefore, additional sequence determinants in the N terminus of ATRX185 (which are absent in ATRX125) are required for ATRX185 targeting toward the 20B-F cytogenetic region. In the future, it will be interesting to define these sequence motifs in the structure of ATRX185.

In a recent report (49) it has been shown that the pericentric focus of D. melanogaster ATRX in polytene chromosomes overlaps with a ∼50-kb satellite block of TAGA repeat. This sequence is not conserved in other Drosophila species, whereas the pericentric localization of ATRX/XNP is. The pericentric ATRX/XNP focus is a major site of replication-independent nucleosome replacement. However, the rapid histone turnover at this site appears to be sequence-dependent and does not require ATRX/XNP. It has also been speculated that the pericentric ATRX/XNP focus contributes to heterochromatic silencing throughout the nucleus, including ectopic loci, such as bwD. We observed that certain variegated transgenes localized to heterochromatic sites outside of the ATRX/XNP focus are not responsive to ATRX (Figs. 3, F and G). Thus, it remains likely that silencing by ATRX does require its physical localization to the cognate loci.

Pericentric beta-heterochromatin is the most widely studied model of silent heterochromatin in vivo in Drosophila. It harbors heterochromatic genes, rRNA genes, repetitive sequences, and retrotransposon insertions, characteristic of “heterochromatin.” The breakpoints of classical chromosome aberrations that exhibit PEV (such as w[m4]) and insertion sites of variegating transgenes are all positioned in beta-heterochromatin. The near elimination of HP1a from pericentric X beta-heterochromatin of xnp/atrx mutant flies reveals an important biochemical activity of ATRX in vivo. It is possible that the ATRX/XNP ATPase is required for efficient ATP-dependent deposition of HP1a into this genomic region. Alternatively, it is possible that most if not all HP1a that is normally associated with this region is present in a complex with ATRX/XNP. In either case, this result validates Drosophila ATRX as a major component and the determinant of pericentric beta-heterochromatin structure and function. The role of ATRX185 in its native complex with HP1a in establishment of beta-heterochromatin identity in the fly X chromosomes is yet another example of variable biochemical functions that SWI2/SNF2-like molecular motors can have in modification of chromatin structure in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Beirit, B. Birshtein, A. Jenny, M.-C. Keogh, A. Lusser, and A. Skoultchi for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions. We thank Y. Studentsov for help with baculovirus techniques. Protein sequencing was performed by the Proteomics Resource Center at Rockefeller University.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM074233 (to D. V. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

- PEV

- position effect variegation

- REA

- restriction enzyme accessibility

- ATRX

- α-thalassemia mental retardation factor

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ATR-X

- α-thalassemia X-linked mental retardation syndrome

- ACF

- ATP-utilizing chromatin assembly and remodeling factor

- RSF

- remodeling and spacing factor

- CHD1

- chromatin-helicase-DNA-binding protein 1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolffe A. P. (1995) Curr. Biol. 5, 452–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger K., Mäder A. W., Richmond R. K., Sargent D. F., Richmond T. J. (1997) Nature 389, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eissenberg J. C., Reuter G. (2009) Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 273, 1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Wit E., van Steensel B. (2009) Chromosoma 118, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fanti L., Pimpinelli S. (2008) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 18, 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallrath L. L. (1998) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 8, 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards E. J., Elgin S. C. (2002) Cell 108, 489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebert A., Lein S., Schotta G., Reuter G. (2006) Chromosome Res. 14, 377–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice J. C., Allis C. D. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 263–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu X., Wontakal S. N., Emelyanov A. V., Morcillo P., Konev A. Y., Fyodorov D. V., Skoultchi A. I. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 452–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yasuhara J. C., Wakimoto B. T. (2008) PLoS Genet. 4, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riddle N. C., Elgin S. C. (2008) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 320, 185–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phalke S., Nickel O., Walluscheck D., Hortig F., Onorati M. C., Reuter G. (2009) Nat. Genet. 41, 696–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miklos G. L., Cotsell J. N. (1990) BioEssays 12, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorbalenya A. W., Koonin E. V. (1993) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 3, 419–429 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisen J. A., Sweder K. S., Hanawalt P. C. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 2715–2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Côté J., Quinn J., Workman J. L., Peterson C. L. (1994) Science 265, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fyodorov D. V., Kadonaga J. T. (2001) Cell 106, 523–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexiadis V., Kadonaga J. T. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 2767–2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., LeRoy G., Seelig H. P., Lane W. S., Reinberg D. (1998) Cell 95, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haushalter K. A., Kadonaga J. T. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 613–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbons R. (2006) Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 1, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbons R. J., Wilkie A. O., Weatherall D. J., Higgs D. R. (1991) J. Med. Genet. 28, 729–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbons R. J., Brueton L., Buckle V. J., Burn J., Clayton-Smith J., Davison B. C., Gardner R. J., Homfray T., Kearney L., Kingston H. M. (1995) Am. J. Med. Genet. 55, 288–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDowell T. L., Gibbons R. J., Sutherland H., O'Rourke D. M., Bickmore W. A., Pombo A., Turley H., Gatter K., Picketts D. J., Buckle V. J., Chapman L., Rhodes D., Higgs D. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13983–13988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lechner M. S., Schultz D. C., Negorev D., Maul G. G., Rauscher F. J., 3rd (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardoso C., Timsit S., Villard L., Khrestchatisky M., Fontès M., Colleaux L. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 679–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue Y., Gibbons R., Yan Z., Yang D., McDowell T. L., Sechi S., Qin J., Zhou S., Higgs D., Wang W. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10635–10640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbons R. J., McDowell T. L., Raman S., O'Rourke D. M., Garrick D., Ayyub H., Higgs D. R. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 368–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrick D., Sharpe J. A., Arkell R., Dobbie L., Smith A. J., Wood W. G., Higgs D. R., Gibbons R. J. (2006) PLoS Genet. 2, e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bérubé N. G., Mangelsdorf M., Jagla M., Vanderluit J., Garrick D., Gibbons R. J., Higgs D. R., Slack R. S., Picketts D. J. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 258–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibbons R. J., Higgs D. R. (2000) Am. J. Med. Genet. 97, 204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerrini R., Shanahan J. L., Carrozzo R., Bonanni P., Higgs D. R., Gibbons R. J. (2000) Ann. Neurol. 47, 117–121 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee N. G., Hong Y. K., Yu S. Y., Han S. Y., Geum D., Cho K. S. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 2625–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong Y. K., Lee N. G., Lee M. J., Park M. S., Choi G., Suh Y. S., Han S. Y., Hwang S., Jeong G., Cho K. S. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 384, 160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bassett A. R., Cooper S. E., Ragab A., Travers A. A. (2008) PLoS One 3, e2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito T., Levenstein M. E., Fyodorov D. V., Kutach A. K., Kobayashi R., Kadonaga J. T. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1529–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamakaka R. T., Kadonaga J. T. (1994) Methods Cell Biol. 44, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pazin M. J., Kamakaka R. T., Kadonaga J. T. (1994) Science 266, 2007–2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fyodorov D. V., Kadonaga J. T. (2002) Nature 418, 897–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallrath L. L., Elgin S. C. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1263–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan C. M., Dobie K. W., Le H. D., Konev A. Y., Karpen G. H. (2002) Genetics 161, 217–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konev A. Y., Yan C. M., Acevedo D., Kennedy C., Ward E., Lim A., Tickoo S., Karpen G. H. (2003) Genetics 165, 2039–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ronsseray S., Boivin A., Anxolabéhère D. (2001) Genetics 159, 1631–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavrov S., Déjardin J., Cavalli G. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 247, 289–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cryderman D. E., Morris E. J., Biessmann H., Elgin S. C., Wallrath L. L. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 3724–3735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorer D. R., Henikoff S. (1994) Cell 77, 993–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lomberk G., Wallrath L., Urrutia R. (2006) Genome Biol. 7, 228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneiderman J. I., Sakai A., Goldstein S., Ahmad K. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14472–14477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]