INTRODUCTION

Early repolarization (significant elevation of the QRS-ST junction in the inferior or lateral ECG leads), thought previously to be a benign entity, was recently shown1,2 to be more prevalent in patients with a history of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI)3,4,6 is a novel noninvasive imaging modality that generates electroanatomic maps of epicardial activation and repolarization.

CASE

Patient #1

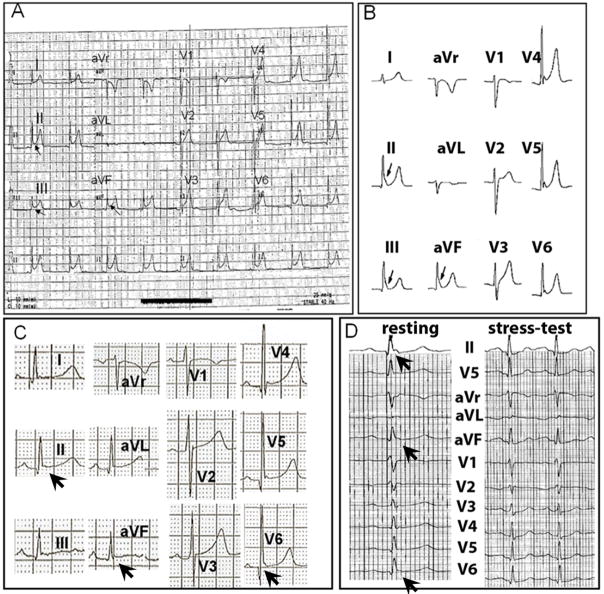

The patient is a 21-year-old Caucasian male whose identical twin brother died two years ago of sudden cardiac arrest. There had been no previous family history of sudden death, syncope, or heart disease prior to the death of the twin. The deceased twin had been in excellent health until he began experiencing palpitations associated with near syncope six months prior to his death. He had a cardiac evaluation, which included an ECG, which showed early repolarization (Figure 1A), and a normal echocardiogram without evidence of structural heart disease. Six months following the cardiac evaluation, the deceased twin expired at age 19 from sudden cardiac death during sleep. An autopsy was normal and revealed no evident heart disease. Figure 1B shows the ECG of the surviving twin with a pattern of early repolarization most prominent in leads II, III and aVF. Myocardial ischemia, structural heart disease and Brugada syndrome were ruled out by exercise testing, MRI and flecainide testing respectively; his condition was diagnosed as early repolarization (ER) abnormality.1 Considering this and the sudden cardiac death of his twin, an ICD was implanted in February 2007.

Figure 1.

Panel A : 12-lead ECG of the deceased twin. Panel B : 12-lead ECG of the surviving twin. Arrows indicate the early repolarization pattern of J-point elevation prominent in leads II, III and aVF of both ECGs. Panel C : 12-lead resting ECG of patient #2. Arrows indicate the early repolarization pattern in leads II, aVF and V6. Panel D: Stress-test ECG of patient #2, showing the resting ECG (left) with the arrows showing the early repolarization pattern (arrows) in leads II, aVF and V6, and the stress-test ECG (right) showing resolution of early repolarization upon exercise.

Patient #2

The patient is a 55-year-old Caucasian male with a prior history of syncope who was found unresponsive along a heavily traveled path in a metropolitan area in September 2006. He received prompt attention from emergency medical personnel who found him pulseless and initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. An automatic external defibrillator was attached revealing ventricular fibrillation (VF) and two shocks (200 J, 360 J) were delivered with restoration of sinus rhythm. As in the case of patient #1, subsequent workup (including ECG, cardiac catheterization, exercise echocardiogram and cardiac MRI) revealed no evidence of ischemia, structural heart disease, Brugada or long QT syndrome. Therefore, the patient’s event was labeled as idiopathic VF and an ICD was implanted prior to discharge. Review of his resting 12-lead ECG (Figure 1C) showed early repolarization in inferior/lateral leads which resolved upon stress test (Figure 1D).

METHODS

ECGI was applied to image the cardiac epicardial activation and repolarization patterns and compare these to previously published data4,5 of normal human cardiac electrophysiology. All study protocols were reviewed and fully approved by Human Research Protection Office at Washington University and informed written consent was obtained from the patients prior to the study. Body-surface ECG potentials, recorded simultaneously from 250 electrodes on the patient torso, were combined with cardiac anatomy from ECG-gated CT to generate noninvasively electroanatomic maps of epicardial activation and repolarization. In addition to sinus beats, two premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) of identical morphologies captured in the recordings in patient #1, and one PVC in patient #2 were also mapped using ECGI.

RESULTS

Patient #1

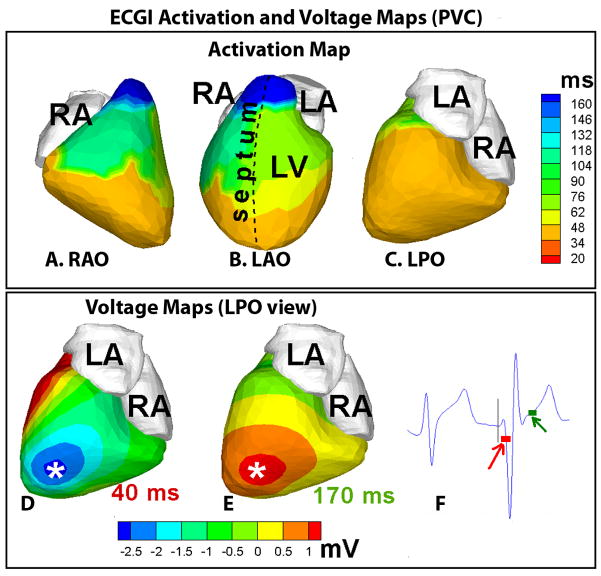

Figure 2, top row (panels A–C) shows the ECGI activation map during a sinus beat in patient #1. Activation initiates from the superior anterior septum (a variant of normal ventricular activation4,5), resulting in early activation (orange to yellow) of anterior RV and LV. There was uniform progression of activation from these early areas, with the posterolateral LV base (light blue, LPO, panel C) and the RV outflow tract (dark blue, RAO view) activating last. There was an area of slightly delayed conduction (by 25 ms) from the base to mid-lateral RV (between regions of yellow-green and light blue, panel A). Conduction delays of such magnitudes (20–25 ms) have been observed in similar anatomic locations in direct mapping studies of conduction in the normal human ventricle by Durrer et al5 (last row, Figure 2). Moreover, areas of early (upper anterior septal aspect below the mitral annulus) and late (posterolateral RV base) activation were also consistent with the observations in the Durrer study5. Figure 2, middle row (panels D–F), shows the ECGI repolarization activation-recovery interval (ARI)4,6 map of the same sinus beat. Regions of abnormally short ARI were observed in mid anterolateral RV (ARI ~140 ms, dark blue, region 1 in RAO and LAO views) and inferior basal RV (ARI ~ 160 ms, light blue, region 3 in LPO view). The previously reported4 value of human ventricular ARI was 235±21 ms (mean ±standard deviation). Even more important to arrhythmogenesis is the observation that very steep localized ARI gradients (107.4 ms/cm in anterolateral RV and 102.2 ms/cm in the inferior basal RV) were present across these areas of abnormally short ARI. ARI gradient is computed as the difference in ARI values between neighboring epicardial nodes divided by the distance between them. The value of ARI gradients in the normal heart computed from previously published data4 ranged from 4.5 ms/cm to 11.3 ms/cm. Representative electrogram from regions with short ARI (1, inset, panel D) showed marked elevation of the QRS-ST junction while electrogram from an adjacent site (2, inset, panel D) did not show any evidence of ER. ECGI ventricular activation isochrones during PVC showed early activation (orange, panels A–C, Figure 3) of a large area of the epicardium including the apex and the inferior wall. ECGI potential maps showed early epicardial breakthrough, indicated by a local potential minimum (asterisk, dark blue, panel D) in the inferior apical area. The potential pattern during the start of repolarization (panel E) mirrored the pattern during early activation with reversed polarity, confirming the origin of PVC in this location.

Figure 2.

Top Row : ECGI activation-map of the patient during a sinus beat in right anterior oblique (RAO, panel A), left anterior oblique (LAO, panel B) and left posterior (LPO, panel C) views. Middle Row: ECGI repolarization activation-recovery interval (ARI) map of the sinus beat in RAO (D), LAO (E) and LPO (F) views. Insets in panel D show epicardial electrograms from adjacent sites marked on the map (1, from the dark blue area with unusually short ARI; 2, from the adjacent area, black line indicating the baseline). RA=right atrium, LA=left atrium, LV=left ventricle. Bottom Row : A map of normal ventricular excitation from the Durrer study5 (direct mapping in isolated human hearts); conduction delay of 20 ms occurred between the area of earliest activation (red) and the more inferior area adjacent to it (green), marked by the arrow-heads. Adapted with permission from reference #5.

Figure 3.

Top row. Panels A–C : ECGI activation map of the premature ventricular complex (PVC). Bottom row. Panels D and E : Left posterior (LPO) views of ECGI epicardial potential maps, 40 ms (D) and 170 ms (E) after onset of QRS. Epicardial breakthrough during early activation, indicated by a local potential minimum, occurs in an inferior apical area (asterisk, dark blue, panel D). This potential minimum is replaced by a potential maximum (asterisk, red, panel E) during early repolarization. Panel F: ECG recording, including the PVC, from a frontal body-surface electrode, close to the precordial lead location V2–V3. The time-origin (indicated by the vertical line) is chosen at the onset of QRS in the PVC beat. The time-points at which epicardial potential maps (in panels D and E) are shown, are indicated by red and green boxes, respectively.

Patient # 2

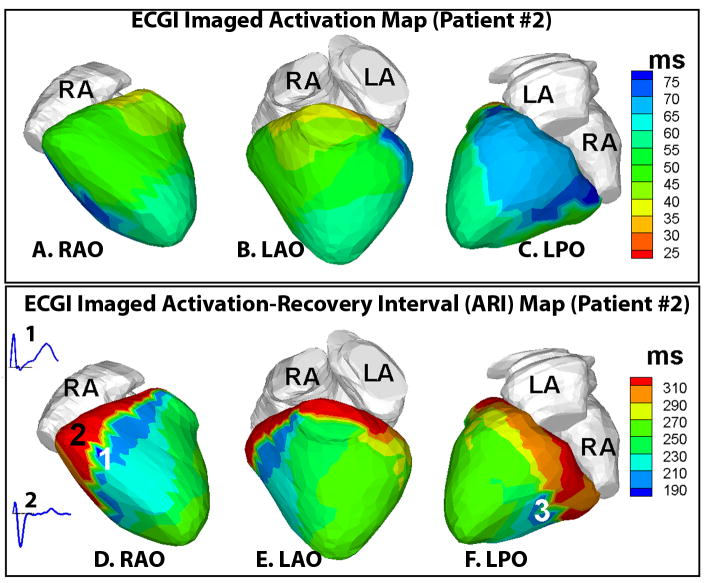

ECGI activation map (Figure 4, panels A–C) in the resting sinus rhythm in patient #2 showed smooth propagation of excitation throughout the ventricular epicardium without significant delays, similar to patient #1. However, the repolarization ARI maps (Figure 4, panels D–F) showed areas of early repolarization (in deep blue, regions 1, panel D, and 3, panel F) with short ARIs (~180–200 ms). Electrograms from these areas in anterior-lateral and posterior-basal RV showed substantial elevation of the QRS-ST segment (inset 1, panel D) while neighboring electrograms (inset 2, panel D) showed flat ST segment. Importantly, abnormally steep localized ARI gradients (261 ms/cm) were observed across these areas of early repolarization. Note that the region of steepest ARI gradient (red to blue, marked 2 and 1 respectively in the ARI map) is in an area of continuous uniform conduction (green in the activation map). The origin of the single PVC in this patient was mapped (by ECGI) to the anterolateral LV base.

Figure 4.

Top row. Panels A–C : ECGI activation map in patient #2 in resting sinus rhythm (A-RAO view, B-LAO view, C-LPO view). Activation initiated from the superior anterior septal aspect (orange, panel B) and propagated smoothly throughout the ventricular epicardium with posterolateral RV and LV base activating late (blue, panel C). Bottom row. Panels D–F : ECGI activation-recovery interval (ARI) maps with areas of early repolarization (short ARI <200 ms, regions 1 and 3 in deep blue, panels D and F respectively). Abnormally large localized ARI gradients (261 ms/cm) are observed across these areas of early repolarization. Inset 1 shows the electrogram from region 1, showing marked elevation of the QRS-ST segment (baseline indicated by the black line). Inset 2 shows the electrogram from neighboring region 2 which has a relatively flat ST segment.

DISCUSSION

The images demonstrate that despite normal ventricular activation, these patients have abnormal repolarization characterized by areas with short ARIs (reflecting short action potentials7). Importantly in the context of arrhythmias is the observation of very steep localized repolarization gradients across these inferior/lateral areas of early repolarization where the electrograms had marked QRS-ST segment elevation. This large local dispersion of repolarization creates steep excitability gradients which provide the substrate for unidirectional block and reentry. The origins of PVC in these patients were remote from the area with high repolarization dispersion. However, if a PVC excitation wavefront were to arrive at the region of steep repolarization gradient at the right time and spatial orientation, unidirectional block and reentrant arrhythmia could be initiated. The ECGI data from both patients support the presence of regions with relatively short action potentials and early repolarization (rather than abnormal late activation) as the mechanism of ER and suggest that abnormally large spatial repolarization gradients may be a cause of proarrhythmia in ER patients. While the findings presented in this case report do not prove that abnormal repolarization is the mechanism of ER, they provide a working hypothesis for systematic studies in larger groups of patients.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Merit Award R37-HL-33343 and Grant R01-HL-49054 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to Y. Rudy. Dr. Rudy is the Fred Saigh Distinguished Professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Y. R. is co-chair of the scientific advisory board and holds equity in CardioInsight Technologies (CIT). CIT does not support any research conducted by Y.R., including that presented here.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, et al. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016–2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haïssaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F, et al. Ventricular fibrillation with prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of KCNJ8/KATP channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;20:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramanathan C, Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ryu K, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2004;10:422–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramanathan C, Jia P, Ghanem R, Ryu K, Rudy Y. Activation and repolarization of the normal human heart under complete physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6309–6314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601533103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durrer D, Van Dam RT, Freud GE, Janse MJ, Meijler FL, Arzbaercher RC. Total excitation of the isolated human heart. Circulation. 1970;41:899–912. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh S, Rhee EK, Avari JN, Woodard PK, Rudy Y. Cardiac memory in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: noninvasive imaging of activation and repolarization before and after catheter ablation. Circulation. 2008;118:907–915. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.781658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haws CW, Lux RL. Correlation between in vivo transmembrane action potential durations and activation-recovery intervals from electrograms: effects of interventions that alter repolarization time. Circulation. 1990;81:281–288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.1.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]