Abstract

Background/Aims

Midgut formation in Drosophila melanogaster is dependent upon the integrity of a signaling loop in the endoderm which requires the TGFβ-related peptide, Decapentaplegic, and the Hox transcription factor, Labial. Interestingly, although Labial-like homeobox genes are present in mammals, their participation in endoderm morphogenesis is not clearly understood.

Methods

We report the cloning, expression, localization, TGFβ inducibility, and biochemical properties of the mammalian Labial-like homeobox, HoxA1, in exocrine pancreatic cells that are embryologically derived from the gut endoderm.

Results

HoxA1 is expressed in pancreatic cell populations as two alternatively spliced messages, encoding proteins that share their N-terminal domain, but either lack or include the homeobox at the C-terminus. Transcriptional regulatory assays demonstrate that the shared N-terminal domain behaves as a strong transcriptional activator in exocrine pancreatic cells. HoxA1 is an early response gene for TGFβ1 in pancreatic epithelial cell populations and HoxA1 protein co-localizes with TGFβ1 receptors in the embryonic pancreatic epithelium at a time when exocrine pancreatic morphogenesis occurs (days E16 and E17).

Conclusions

These results report a role for HoxA1 in linking TGFβ-mediated signaling to gene expression in pancreatic epithelial cell populations, thus suggesting a high degree of conservation for a TGFβ/labial signaling loop in endoderm-derived cells between Drosophila and mammals.

Key Words: Transactivation, AR4IP, Early response gene, Ductular pancreas, Labial

Introduction

Members of the HOX family of homeodomain-containing transcription factors play a fundamental role in pattern formation and organogenesis during the development of organisms ranging from worms to vertebrates [1,2,3]. In Drosophila melanogaster, the organism in which HOX genes were first identified, the HOM-C complex of HOX genes are expressed along the antero-posterior body axis following the same order as they are arranged in the genome. Although more complex, the organization of orthologous HOX genes in mammals follows a similar pattern: four clusters of mouse HOX genes (HoxA-HoxD) are present on different chromosomes and display a temporal and spatial pattern of expression related to their position within the cluster. The HOX genes that occupy similar positions within each chromosomal cluster, called paralogs, exhibit high structural homology within their DNA-binding motifs with its orthologous gene in D. melanogaster, and suggest these factors perform analogous functions during development.

The role of Labial-related HOX genes during head development represents a clear example of HOX functional conservation throughout evolution. In Drosophila, labial is expressed in the most anterior segments of the fly and is crucial for the formation of head structures [4,5,6]. Similarly, the murine Labial-related gene, HoxA1, is also expressed within distinct anterior regions of the mouse hindbrain and its disruption by homologous recombination results in severe abnormalities in the hindbrain, inner ear, and cranial nerve development [7,8,9,10]. Furthermore, variants in human HoxA1 have recently been associated with the autism-associated disorders Bosley-Salih-Alorainy syndrome and Athabascan brainstem dysgenesis syndrome [11,12,13]. Together, these data indicate that Labial members of homeobox genes are similarly expressed, and share a conserved role in specifying anterior pattern formation in different organisms.

In Drosophila, labial is not just restricted to anterior head structures, but it also represents the only Drosophila HOM-C gene that is expressed in the endoderm [4,6]. Here, it participates in midgut development in response to the TGFβ-like growth factor, Decapentaplegic (Dpp) [14,15,16,17,18]. Interestingly, recent microarray studies suggest that in contrast to Drosophila labial, murine HoxA1 may actually suppress endodermally-derived cell fates and promote ectodermal and mesodermal fates [19,20]. On the other hand, HoxA1 expression is readily detected in early foregut endoderm during mouse embryogenesis [21]. Thus, although the role for the Labial-related HoxA1 factor is somewhat understood in central nervous system structures, its function in endodermal development remains unclear.

The pancreatic epithelium originates from the mammalian gut endoderm, and similarly to the Drosophila gut, members of the TGFβ signaling pathway are known to regulate the differentiation of cells in this tissue [22,23]. Thus, this tissue offers an attractive model for testing whether Hox genes are important for regulating similar events in a mammalian system. Using degenerate PCR for HOX factors, we show in this study that the Labial-related Hox gene, HoxA1, is expressed in the rat pancreas, co-localizes with TGFβ receptors in the developing pancreatic epithelium during late embryogenesis and, similarly to Drosophila labial, HoxA1 expression is upregulated by TGFβ-mediated signaling cascades. Molecular characterization of HoxA1 indicates the presence of two alternatively spliced variants encoding a homeobox-containing and a homeobox-less protein that share a 120 amino acid N-terminal domain. Using a heterologous transcriptional regulatory assay, we find that this shared region functions as a potent transcriptional activation domain in pancreatic epithelial cell lines. Together, these results reveal a role for HoxA1 as a transcription factor in pancreatic epithelial cells and provide a characterization of the transcriptional activating function of this protein. These data also uncover a striking parallel between the regulation of fly and mammalian Labial-like HOX genes by TGFβ-like signaling pathways in endoderm-derived tissue.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of the Rat HoxA1 Full-Length cDNA and PCR Amplification of HoxA1 from Pancreatic Cell Populations

Sequences encoding the DNA-binding motif of the labial-like genes HoxA1 and HoxB1 were isolated from rat pancreas cDNA using degenerate PCR primers for the highly conserved homeobox-encoding sequences EKEFHFN and IWFQRRMK [24]. PCR amplification, cloning, sequencing, and DNA analysis were performed as previously described [25]. A rat pancreas cDNA library (λ ZAP II, Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif., USA) was screened using the PCR-amplified HoxA1 cDNA as a probe as previously described [26]. A cDNA clone corresponding to approximately 85% of the coding region and over 1 kb of the 3′ untranslated region was obtained from this screening. The remainder of the HoxA1 coding region was obtained from a rat genomic DNA library (λ Dash II, Stratagene) using a cDNA fragment spanning nt 250 to nt 380 of the rat HoxA1-encoding cDNA as a probe. For the amplification of alternatively spliced forms of rat HoxA1, a forward primer 5′-GTCACTCAGTGACAGATGGA-3′ surrounding the initiation codon, and a reverse primer 5′-CTGGAGAAGACGTCTCTGAA-3′ flanking the intron/exon boundary upstream of the homeobox domain within HoxA1 was used. The PCR amplification reaction was carried out for 30 cycles of 95°C, 1 min; 55°C, 2 min, and 72°C, 3 min, and the resulting cDNAs were cloned and sequenced. Human HoxA1 was amplified from human ductal adenocarcinoma-derived exocrine pancreatic cell lines using the following primers: forward 5′-ATGAACTCCTTCCTGGAATA-3′ and reverse 5′-CGTACTCTCCAACTTTCCC-3′ [27] using the same cycling conditions as above.

Cell Culture: RNA Preparation and Northern Blot Analysis

All cell lines described were obtained from American Type Culture Conditions (ATCC, Rockville, Md., USA) and cultured according to supplier's suggestions. For experiments on the TGFβ-mediated regulation of HoxA1 gene expression in the pancreatic cell line AR4IP, cells were serum-starved for 24 h prior to treatment with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 (Austral Biologicals, San Ramon, Calif., USA) in DMEM containing 1% FBS for different periods of time before RNA extraction. 10 mg/m1 cycloheximide (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo., USA) was applied 30 min prior to and during TGFβ1 treatment for the early response experiments. For TGFβ1 regulation of HoxA1 in embryonic pancreatic cells, pancreata were removed from prenatal day 17 (E17) Sprague-Dawley pups, washed briefly in DMEM containing 1% FBS, and minced on ice using small surgical scissors. Samples were then treated with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 at 37°C for different periods of time before RNA extraction. RNA was extracted and Northern blot analysis was performed as previously described [26]. A full-length HoxA1 cDNA was used as a probe and expression was normalized to the level of GAPDH mRNA or 18S rRNA after blot rehybridization.

Western Blot Analysis and Immunofluorescence

Protein lysates were prepared and western blot analysis was performed as described by Cook et al. [28]. The HoxA1 protein was detected using a polyclonal antibody against a conserved mouse HoxA1 peptide, PISPATPPGSDEKTE, prepared by Berkeley Antibody Co. (Richmond, Calif., USA), and a goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase-labeled secondary antibody (Promega Corp., Madison, Wisc., USA). The characterization of this antibody was performed using a GST-HoxA1 fusion protein assembled by cloning the full-length HoxA1 cDNA in-frame with glutathione-S-transferase (GST) into the vector, pGEX-2T (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J., USA). Bacteria were induced to express GST-HoxA1 with the addition of 2 mM 1PTG for 2 h and the recombinant protein was purified over a GST Sepharose column according to the manufacturer's suggestions (Pharmacia). Specificity of the antibody was tested by pre-adsorbing the antibody with an excess of GST-HoxA1 fusion protein at 37°C for 60 min and pelleting the immune complex at 12,000 g for 30 min. The resulting antisera were used for western blot, indirect immunofluorescence, or immunohistochemistry analyses. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed as previously described [29].

lmmunohistochemistry

The developmental pattern of expression of HoxA1 in rat pancreas was performed by immunohistochemistry methods as previously described [28] on whole-mount paraffin-embedded rat embryos. Immunoperoxidase staining was performed with the polyclonal antibody against the mouse HoxA1 peptide as described above using an avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase detection system with aminoethylcarbazole as a substrate (Zymed, San Francisco, Calif., USA). As a control, the antibody pre-adsorbed with the GST-HoxA1 fusion protein (see above) was used. Antibodies against the TGFβ receptors type I and II (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif., USA) and insulin and α-amylase (Sigma) were used according to the manufacturer's suggestions.

GAL4-Based Transcriptional Regulatory Assay

For the characterization of the transcriptional regulatory activity of HoxA1, deletion constructs were prepared that span from the initiation codon to the homeobox DNA-binding motif. DNA fragments corresponding to amino acids 1–74, 1–122, 101–122, 75–100, 75–122, 1–245, and 123–245 were generated by restriction enzyme digestion or PCR amplification, cloned in-frame with the GAL4 DNA-binding motif present in the effector vector pSG424 (kindly provided by Dr. Zeleznik-Le, University of Chicago), and verified by sequencing. These constructs were co-transfected into PANC-1 cells along with a reporter construct carrying five GAL4-binding sequences upstream of the TK (thymidine kinase) basal promoter driving the expression of the CAT (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) reporter gene. Transfection of pancreatic cells was performed using LipofectAMINE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif., USA). Co-transfection with a plasmid expressing β-galactosidase, pHook-Lac (Invitrogen), was performed to control for transfection efficiency. Relative CAT activity was assayed using an ELISA method as described by Roche (Indianapolis, Ind., USA). In all experiments, CAT activity was determined using the same amount of protein and the values were normalized using β-galactosidase.

Results

HoxA1 Is Expressed during Exocrine Pancreatic Development

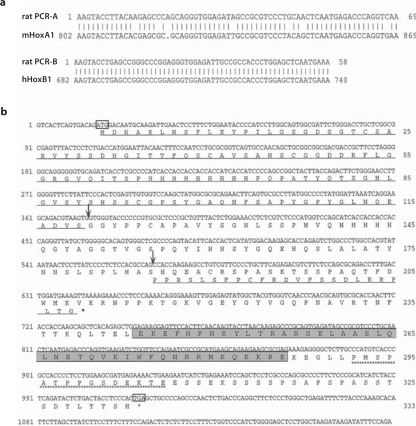

We initially searched for the expression of labial-like genes in rat pancreas using degenerate PCR primers for the highly conserved homeobox domain encoding the sequences EKEFHFN and WFQRRMK [24]. Using this approach, we amplified two different fragments which encode the homeobox motifs for the Labial-like rat HoxA1 and HoxB1 paralogs (fig. 1a). Since HoxB1 is a likely downstream target for HoxA1 [30,31,32], we focused on HoxA1 as a molecular and functional paradigm for this family of mammalian labial-like genes. To confirm the expression of this gene in the rat pancreas, we screened a rat pancreas cDNA library with the PCR-HoxA1 probe and identified a 2.2-kb cDNA clone that spans approximately 85% of the coding region and over 1 kb of the 3′ untranslated region of the rat HoxA1 homolog. The remainder of the rat HoxA1 coding sequence was ascertained from an overlapping DNA clone obtained from a rat genomic library (fig. 1b). Further analysis of the genomic clone indicated that, similar to the murine gene [33], the genomic structure of the rat HoxA1 gene contains an intron upstream of the sequence encoding the homeodomain (fig. 1b) (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Expression of labial-like genes in rat pancreas containing the highly conserved homeobox domain. a A pancreas cDNA library was used as a template in a PCR amplification using degenerate primers for the highly conserved homeobox domain encoding for the sequences EKEFHFN and IWFQRRMK, which resulted in the amplification of two different fragments encoding the homeobox motifs for the Labial-like rat HoxA1 and HoxB1 paralogs. The sequences obtained from the PCR-amplified cDNAs, rat PCR-A and rat PCR-B, were used for FASTA analysis against sequences deposited in the GenBank database using GCG analysis software. Since the homeobox domain of many members of this family is highly conserved, the sequences were compared at the DNA level to make more meaningful comparisons. Note that rat PCR-A compared closely (98%) with the homeobox-encoding domain of the murine HoxA1 and that rat PCR-B was almost identical to the human HoxB1. b Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the rat HoxA1 gene is depicted. The full-length coding sequence of rat HoxA1 was obtained by pancreas cDNA and genomic library screening. Nucleotides are numbered at left, amino acids are numbered at right, and the initiator and termination codons are boxed. The homeobox motif is boxed. Arrows represent the donor and acceptor sites for an alternative splicing event which leads to a frameshift in translation and a premature termination (represented in bold type, see fig. 4). The peptide region used to generate a polyclonal antibody against the homeobox-containing HoxA1 is underlined with asterisks. Overall, rat HoxA1 is 96% similar to the mouse homolog at the DNA level and almost identical (99%) at the protein level as determined using FASTA analysis (GCG, Madison, Wisc., USA).

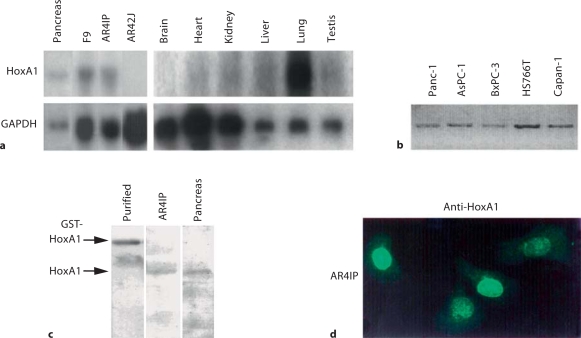

To better define the expression of HoxA1 in pancreatic cell populations, we performed Northern blot analyses from RNA isolated from rat pancreas, rat pancreatic cell lines, and several adult tissues (fig. 2a). HoxA1 was detected in the rat pancreas and the ductular-like exocrine pancreatic cell line AR4IP, but not the acinar-like cell line AR42J. Outside of the pancreas, we detected high levels of HoxA1 expression in lung (fig. 2a). Using RT-PCR, we also detected human HoxA1 from five differentexocrine pancreatic cell lines (fig. 2b). Together, these results demonstrate that HoxA1 is expressed in a broad range of exocrine pancreatic cell populations.

Fig. 2.

Expression of HoxA1 is found in adult rat tissues and exocrine pancreatic cell lines. a Northern blot analysis was performed on total cellular RNA (20 μg) isolated from the poorly differentiated ductular-like rat exocrine pancreatic cell line, AR4IP, and from the adult rat tissues, pancreas, brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, and testis. GAPDH was used to normalize loading. Note that HoxA1 was enriched in the pancreatic cell populations. In addition, high levels of HoxA1 expression were detected in lung. b PCR amplification of HoxA1 from five human ductular-like pancreatic cell lines, PANC-1, AsPC-1, BxPC-3, HS 766T, and Capan-1. Note that HoxA1 was expressed in each of these pancreatic cell lines. c Recombinant GST-HoxA1 was purified from bacteria, and 5 mg of the fusion protein was used as a positive control for a polyclonal HoxA1 antibody derived from a mouse HoxA1 peptide sequence by Western blot analysis. The anti-HoxA1 antibody recognized this purified GST fusion protein at its anticipated MW of 66 kDa. Western blot analysis of homogenates (50 μg) from whole rat pancreas and the exocrine pancreatic cell line AR4IP detects a single polypeptide which has a MW of 47 kDa. Western blot analysis using pre-adsorbed antisera was negative (data not shown). d Indirect immunofluorescence of HoxA1 in AR4IP cells. Cells were plated on coverslips and processed for immunofluorescence using HoxA1 antisera as a primary antibody. Note that HoxA1 localized to the nucleus in the exocrine pancreatic cell line. AR4IP. This localization was not detected in cells stained with pre-immune serum (data not shown).

Based on the importance of HOX factors during organogenesis of other tissues, we next examined the expression and location of the HoxA1 protein during pancreatic development. For this purpose, we created a polyclonal antibody against a peptide corresponding to amino acid residues 292–306 of the HoxA1 sequence. Western blot analysis of a bacterially expressed GST-HoxA1 fusion protein revealed the detection of a single band of the appropriate molecular weight. Moreover, lysates isolated from adult rat pancreas and AR4IP pancreatic cells demonstrated that this antibody specifically recognizes a single protein with the expected relative mobility of approximately 47 kDa (fig. 2c). Pre-adsorption of this antibody with the GST-HoxA1 fusion protein interfered with the detection of this 47-kDa band, while pre-adsorption with GST alone did not affect its specificity (data not shown). Using the HoxA1 antisera for indirect immunofluorescence, we found that HoxA1 is localized to the nucleus of AR4IP cells (fig. 2d), while such subcellular localization is not detected in AR42J cells or using pre-immune serum alone (data not shown). Together, these results confirmed that the HoxA1 protein is expressed in a subset of pancreatic cell populations, prompting us to investigate the localization of this protein during early pancreatic morphogenesis.

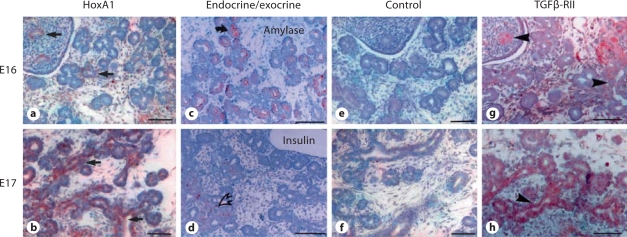

To determine the expression of HoxA1 in the developing pancreas, we immunostained pancreata isolated from embryonic days E16 and E17 using either complete antisera or antisera pre-adsorbed with the GST-HoxA1 fusion protein (fig. 3). Our results demonstrated that HoxA1 is expressed in the developing rat pancreas at both E16 and E17 in cells from the ductular-like structures which are known to give rise to exocrine cell populations (arrows, fig. 3a, b) [34]. Control staining using a marker for differentiated acinar exocrine cells (α-amylase, fig. 3c) and endocrine islet cells (insulin, fig. 3d) confirmed that the HoxA1 staining was positive within the ductular compartment of the gland. Pre-adsorption of the HoxA1 antibody shows no immunostaining, indicating the specificity of our antibody (fig. 3e, f).

Fig. 3.

HoxA1 is expressed in the developing rat pancreas. Immunohistochemistry of developing rat pancreas at embryonic day 16 (E16) (a, c, e, g) or embryonic day 17 (b, d, f, h). Immunolocalization of HoxA1 was performed using HoxA1 antisera (a, b). The exocrine and endocrine portions of the gland were detected using anti-α-amylase and anti-insulin, respectively (c, d), while control staining was performed using the HoxA1 antisera pre-adsorbed with purified GST-HoxA1 fusion protein (e, f). Note that HoxA1 was detected at both E16 and E17 in the ductular-like pancreatic precursor cells (arrows), which give rise to exocrine pancreatic cell populations, and that this immunoreactivity was abolished upon pre-adsorption of the antibody (e, f). Co-localization of the TGFβ receptor type I (data not shown) and II (g, h) showed staining in the exocrine pancreas in a similar distribution as HoxA1. Bars = 100 μm.

Since the Drosophila labial gene is regulated by the TGFβ-related peptide, Dpp, in the gut endoderm, we next tested whether HoxA1 is co-expressed in regions of the pancreas that express the TGFβ receptor. As shown in figure 3g and h, the TGFβ receptor type II was expressed at the same developmental stages and within the same ductular-like structures of the embryonic pancreas as detected for HoxA1. Therefore, HoxA1 is expressed in the developing exocrine pancreas in cells which stains positive for markers of TGFβ signaling.

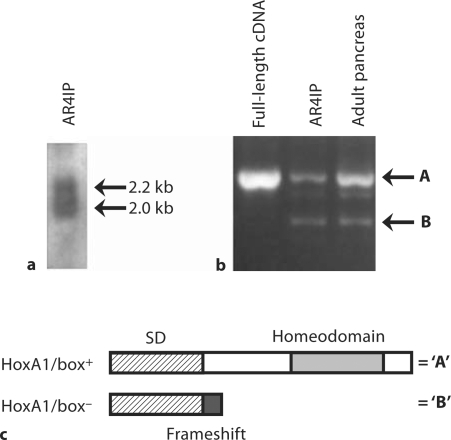

HoxA1 Expression Is Regulated by TGFβ1 in Exocrine Pancreatic Cell Populations

Based on the co-localization of HoxA1 and TGFβ receptors in vivo, we next tested the hypothesis whether, similar to Drosophila labial, HoxA1 functions as a target for TGFβ-mediated signaling cascades in pancreatic cell populations. For this purpose, we used AR4IP pancreatic cells which express detectable amounts of HoxA1 by northern blot analysis. Close analysis of HoxA1 expression in these cells showed the presence of two different transcripts of 2.2 and 2.0 kb (fig. 4a), suggesting that pancreatic epithelial cells express alternatively spliced HoxA1 mRNAs. Indeed, splice variants of the murine HoxA1 gene have been observed in the teratocarcinoma F9 cell line, and these variants are differentially expressed throughout normal embryogenesis [21,33]. We used PCR we tested whether similar spliced forms are expressed in rat AR4IP cells. These studies confirmed the presence of two distinct HoxA1 cDNAs from pancreatic cell populations, and these correspond to the alternatively spliced variants of murine HoxA1 [33] (fig. 4b). Sequence analysis demonstrated that the smaller of the two cDNAs represents an alternatively spliced variant which produces a frameshift in the open reading frame at residue 120, causing a premature termination of the protein, while the largest amplified product is derived from the non-spliced coding sequence (fig. 1b, 4c). Thus, the larger molecular weight PCR product (‘A’) represented a transcript that encodes a protein which contains the HoxA1 homeobox (HoxA1/box+), while the smaller band (‘B’) corresponded to a homeobox-minus (HoxA1/box–) product (fig. 4b, c).

Fig. 4.

Amplification of alternatively spliced forms of HoxA1 from pancreatic populations. a To better determine the size of the HoxA1 transcript, 40 μg of total RNA from AR41P cells were separated further by agarose gel electrophoresis and used for Northern blot analysis. HoxA1 was expressed in these cells as a 2.2-kb and a 2.0-kb transcript. b PCR analysis of alternatively spliced forms of HoxA1 from pancreatic populations. Primers were designed against the rat HoxA1, which flank the intron/exon boundaries within the gene and used in PCR amplification against cDNA derived from the full-length rat HoxA1 cDNA, AR4IP cells, and adult rat pancreas. The upper arrow indicates the expected size product of a full-length homeobox-encoding mRNA, while the lower arrow designates the expected size of an alternatively spliced message previously reported by LaRosa and Gudas [33]. Note that the pancreatic populations, AR41P and adult rat pancreas, express both the full-length rat HoxA1 (A) and an alternatively spliced transcript (B). c Schematic diagram of the alternatively spliced forms of HoxA1. The cDNAs amplified in b were cloned, sequenced and shown to encode a homeobox-containing (HoxA1/box+) (‘A’) and a homeobox-less (HoxA1/box–) (‘B’) protein. This latter product is a result of a frameshift which occurs at the site of splicing, causing a premature termination of the protein sequence (also see fig. 1).

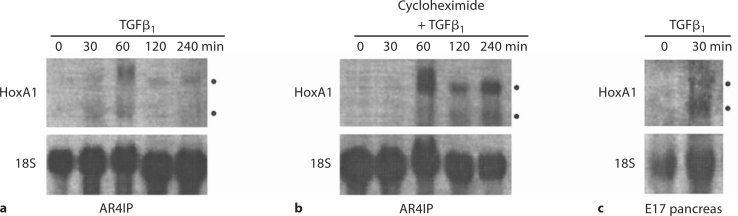

Next, we analyzed the regulation of both HoxA1 transcripts in AR4IP cells treated with or without TGFβ1. The results from this experiment demonstrated that the levels of both HoxA1 mRNAs were upregulated by this growth factor in AR4IP cells as early as 30 min and peaked within 1 h after treatment (fig. 5a). This upregulation was not abolished by the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, indicating that HoxA1 is an early response gene for TGFβ signaling (fig. 5b). In addition, Northern blot analysis on pancreatic cell populations from prenatal day 17 rat embryos treated with TGFβ1 detected an upregulation in the expression of HoxA1 as early as 30 min after TGFβ1 stimulation in embryonic tissue (fig. 5c). These results demonstrated that the HoxA1 gene is a target for TGFβ1-mediated signaling cascade in pancreatic cell populations.

Fig. 5.

Regulation of HoxA1 expression in response to TGFβ1 in pancreatic cell populations. a, b AR4IP cells were treated with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 0, 30, 60, 120, or 240 min in the absence (a) or presence (b) of the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide. RNA was extracted, separated on a 1.5% gel, and used for Northern blot analysis for HoxA1 gene expression. Note that a significant increase in both HoxA1 mRNAs occurred within 1 h of growth factor stimulation. This upregulation was independent of protein synthesis, indicating that HoxA1 is an early response gene for this peptide growth factor in exocrine pancreatic cell populations. c Pancreata were isolated from day 17 prenatal rats, minced, and treated with or without 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 30 min. RNA was extracted and used for Northern blot analysis for HoxA1 gene expression. Note that an increase in both HoxA1 mRNAs occurred within 30 min of growth factor stimulation.

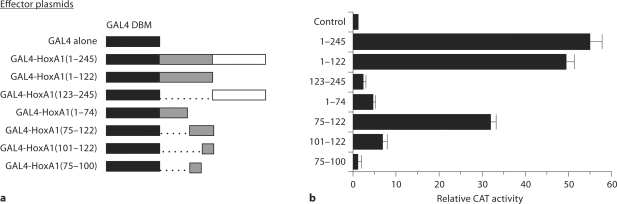

Shared N-Terminus between HoxA1 Isoforms Functions as a Transcriptional Activation Domain

Both isoforms of HoxA1 expressed in pancreas, the HoxA1 homeobox-containing (HoxA1/box+) and homeobox-minus (HoxA1/box–) proteins, are identical within the first 120 amino acids, which wecalled the HoxA1 ‘shared domain’ (SD, fig. 4c). Based on the facts that both forms of HoxA1 are conserved in different species and cell types, and they share the first 120 amino acids of the N-terminal domain outside the DNA-binding motif, we hypothesized that this portion of the molecule may be involved in transcriptional regulation. To test this idea, we took advantage of a commonly used assay for analyzing the function of transcription factor proteins in mammalian cells, the GAL4-based transactivation system [35]. We first tested the ability of the entire N-terminal domain present within the HoxA1-box+ protein (amino acids 1–245) to regulate transcription if fused to the DNA-binding motif of the yeast GAL4 transcription factor. As shown in figure 6a, when this construct was transfected along with a GAL4-responsive CAT reporter plasmid into the highly transfectable exocrine pancreatic cell line, PANC-1, it stimulated transcription 57.0 ± 2.4-fold above that observed using the control GAL4 DNA-binding domain alone (fig. 6b), indicating that the N-terminus of HoxA1 is a strong transcriptional activator. Next, we tested the shared domain (amino acids 1–122) versus the region from amino acids 123–245, present only in the HoxA1/box+ and found that the shared domain activated transcription by 50 ± 2.1-fold above the control value, whereas 123–245 activated transcription only 2.2 ± 0.1-fold over control. To further refine the transactivation domain from within the first 122 amino acids of the Hox sequence, we tested constructs containing amino acids 1–74 and 75–122, and found that the first 74 amino acids, GAL4-HoxA1 (1–74), displayed transactivating properties approximately 10% of the full transactivation ability of the shared domain, stimulating transcription by 4.9 ± 0.5, while GAL4-HoxA1 (75–122) exhibited transactivating properties of over 31.9 ± 1.1, ∼65% of the activity of the 1–122 domain (fig. 6b). Further division of this region, however, showed a significant reduction in activity, with amino acids 101–122 exhibiting 7.0 ± 1.1 activation and amino acids 75–100 showing activity equivalent to the GAL4 DNA-binding motif alone. Together, these functional data demonstrated that HoxA1 is a potent transcriptional activator in exocrine pancreatic cell populations and that the transactivating properties of this protein primarily reside within a 47 amino acid region (amino acids 75–122), which is shared between both alternative spliced variants.

Fig. 6.

A transcriptional activation domain is located within the HoxA1 N-terminal shared domain. a Diagram of the DNA constructs and experimental strategy for determination of the transactivation properties of HoxA1. These distinct effector plasmids were co-transfected into the pancreatic cell line, PANC-1, along with the reporter plasmid carrying five GAL4 recognition sites upstream of the CAT gene. As a control for basal transcriptional activity, the CAT reporter plus the GAL4 DNA-binding motif alone (GAL4 DBM) effector plasmid was used. b Histogram of the CAT activity using the reporter constructs with the various GAL4 DBM-HoxA1 effector plasmids. The GAL4 DNA-binding domain alone (Control) had a basal transcriptional activity of 1.0 ± 0.1, the entire N-terminal 245 amino acids of HoxA1/box+, GAL4-HoxA1(1–245), stimulated transcription 54 ± 2.4-fold over basal activity, the shared domain ‘SD’ between HoxA1/box+ and HoxA1/box–, GAL4-HoxA1 (1–122), activated transcription 48 ± 2.1-fold above the control value, GAL4-HoxA1 (1–74) activated transcription 4.88 ± 0.6, and GAL4-HoxA1 (123–245), the residues unique to HoxA1/box+, activated transcription only 1.9 ± 0.1-fold over control. Note that the GAL4-HoxA1 shared domain (amino acids 1–122) behaved as a transcriptional activator, as effectively as the entire N-terminal region of HoxA1/box+, while the most N-terminal region of the shared domain (1–74), as well as the region unique to HoxA1/box+ (123–245) showed transactivation properties with less than 10% of this value. However, the second portion of the shared domain, GAL4-HoxA1 (75–122), exhibited ∼65% transactivating properties of the entire shared domain. Further division of this region (amino acids 75–100 and 101–122) showed a significant reduction in activity, indicating that the transactivating properties of this protein reside within a 47 amino acid region (amino acids 75–122), which is shared between both alternative spliced variants of this gene product. CAT activity was determined using an ELISA assay (Roche). A plasmid carrying β-galactosidase, pSV-β-galactosidase (Promega) was also co-transfected in order to normalize values to β-galactosidase activity measured using a colorimetric enzyme assay system (Promega). Each experiment was performed independently at least two times in triplicate. Bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Members of the TGFβ family of peptides are important regulators of pancreatic morphogenesis and homeostasis. For instance, these growth factors are critical for maintaining an appropriate balance between the number of exocrine and endocrine cells during pancreatic development through the regulation of both cell proliferation and programmed cell death, and alterations in these normal morphogenetic pathways have been linked to the development of pancreatic cancer [22,23,36]. Consequently, the identification of transcription factor-encoding genes which are expressed in the developing pancreas and are targets for TGFβ peptides in exocrine pancreatic cells, is important for expanding our knowledge of the molecular machinery involved in these signaling pathways and is crucial for a better understanding of the cellular events underlying pancreatic morphogenesis.

In the current study, we demonstrate the developmental expression, TGFβ-inducibility, and transcriptional regulatory properties of the rat Labial-like transcription factor, HoxA1, in pancreatic epithelial cell populations. Analysis of the HoxA1 homeodomain demonstrated that this transcription factor is a member of a protein family for which the Drosophila labial gene product is the structural paradigm. Consistent with the possibility that HoxA1 and Labial are functional orthologs, labial has been shown to be responsible for specifying the formation of anterior structures in the fly, while mouse HoxA1 is expressed in the anterior part of the central nervous system where it plays a crucial role in the formation of rhombomeres and auditory organs during development [8,9,10,37]. Even more relevant to the current study, however, is that labial is the only HOM-C homeobox-encoding gene expressed in the Drosophila endoderm, where it participates in gut morphogenesis in response to the TGFβ-like peptide, Dpp. In light of the fact that both HoxA1 and labial are highly homologous within the DNA-binding motif, are expressed in endoderm-derived cells, and are targets of TGFβ-like pathways, it is tempting to speculate that they may also regulate genes with homologous functions during gut development as well. The identification of genes which are regulated by both of these proteins constitutes a significant undertaking, but will no doubt be beneficial in testing the validity of this hypothesis.

Two previous reports on the characterization of the alternatively spliced variants of the murine HoxA1 gene are conflicting in the primary structure of these mRNAs [33,38]. In the current study, we demonstrate that pancreatic cell populations in vitro and in vivo express two different HoxA1 mRNAs, which migrate as 2.2- and 2.0-kb products, respectively. The sequence analyses reported here are in complete agreement with the study of LaRosa and Gudas [33] which indicates that the murine Hoxa-1 gene encodes proteins with and without a DNA-binding domain. Interestingly, LaRosa and Gudas demonstrated that both Hoxa-1 transcripts are regulated by retinoic acid but with different kinetics in F9 cells: the homeobox-containing HoxA1 transcript was increased as early as 2 h by all-trans-retinoic acid, while the homeodomain-lacking HoxA1 mRNA required approximately 12 h for its upregulation. Here, we show that, in contrast, both HoxA1 transcripts are upregulated by TGFβ1 in epithelial pancreatic cell lines with similar kinetics. We also demonstrate that HoxA1 is an early response gene for TGFβ1, being upregulated by this growth factor even in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. This finding supports the idea that HoxA1 must be activated immediately upon growth factor stimulation in order to regulate downstream gene products. Therefore, together, these results indicate that different morphogenetic stimuli regulate the levels of the HoxA1 mRNAs differently and may reflect underlying functional differences for this transcription factor in mediating the effects of individual signaling pathways.

A very important observation of this work is the fact that the N-terminal domain, which is shared by both alternatively spliced variants of HoxA1, is able to activate transcription in pancreatic epithelial cells. This constitutes solid biochemical evidence supporting a role for HoxA1 as a transcriptional activator and begins to define the functional properties of the different isoforms of HoxA1. Interestingly, similarly to HoxA1, other homeobox-encoding genes, such as the HoxA9, HoxB7, and HoxB6 [39,40,41,42], also give rise to proteins with and without the homeodomain and share the N-terminal domain. Moreover, in the case of HoxA9, the homeodomain-minus form is able to recruit similar co-activators as the homeodomain-containing form [43], providing further evidence that homeobox-lacking transcription factors may provide an additional mechanism of HOX-mediated transcriptional control. This data underscores the likely importance of discovering the short form of Hox-A1, which lacks the homeodomain, in exocrine pancreatic cells, since it may fuel further investigations on the mechanisms by which these proteins function. Therefore, further functional characterization of homeobox-minus isoforms, such as those described here, should serve as a useful model for determining the role of these homeobox-minus proteins in vivo.

An additional noteworthy finding of this report is that the expression of another labial-like gene, HoxB1, is detected in pancreas by PCR (fig. 1a). Interestingly, HoxA1 has been previously shown to be co-expressed with HoxB1 during hindbrain development in mouse and these genes appear to cooperate with the zinc finger transcription factor Krox-20 to specify the formation of the rhombomeres 4 through 6 of the developing hindbrain [8,9,10,37]. Therefore, the presence of both paralog genes in the pancreas suggests that an analogous loop may also regulate some aspects of pancreatic morphogenesis. Future studies focused on characterizing the potential functional interaction among these gene products in the pancreas should provide further insight into the role of Labial-like proteins as pancreatic transcription factors.

In conclusion, the results here report the first evidence that HoxA1 functions as a TGFβ early response gene in endodermally-derived rat exocrine pancreatic cell populations, and is co-expressed with TGFβ receptors during exocrine pancreatic development. Since the Drosophila gene labial is also regulated by a TGFβ-like peptide, Dpp, in endoderm tissues, our results suggest a conserved participation of labial-like genes in these related signaling cascades across evolution. We have also functionally characterized the transcriptional regulatory activity of HoxA1 and demonstrated that a small N-terminal region behaves as a transcriptional activator in exocrine pancreatic cell populations. Together, these results support a role for HoxA1 as a nuclear link between TGFβ1-mediated pathways and gene expression in endodermally-derived exocrine pancreatic cells.

Acknowledgements

We thank Toni Anderson from Berkeley Antibody Co. (Richmond, Calif., USA) for use of the HoxA1 antibody and Dr. Zeleznik-Le (University of Chicago, Chicago Ill., USA) for providing us with the GAL4 vector pSG424. This work was supported by the Mayo Foundation, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK P30DK084567), NIH DK52913 (R.U.), NIH EY017907 (T.A.C), and NIH GM079428 (B.G).

References

- 1.Manak JR, Scott MP. A class act: conservation of homeodomain protein functions. Dev Suppl. 1994:61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botas J. Control of morphogenesis and differentiation by HOM/HOX genes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappen C, Ruddle FH. Evolution of a regulatory gene family: HOM/HOX genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:931–938. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90016-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diederich RJ, Merrill VK, Pultz MA, Kaufman TC. Isolation, structure, and expression of labial, a homeotic gene of the antennapedia complex involved in Drosophila head development. Genes Dev. 1989;3:399–414. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merrill VK, Diederich RJ, Turner FR, Kaufman TC. A genetic and developmental analysis of mutations in labial, a gene necessary for proper head formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1989;135:376–391. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mlodzik M, Fjose A, Gehring WJ. Molecular structure and spatial expression of a homeobox gene from the labial region of the antennapedia-complex. EMBO J. 1988;7:2569–2578. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lufkin T, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Mark M, Chambon P. Disruption of the Hox-1.6 homeobox gene results in defects in a region corresponding to its rostral domain of expression. Cell. 1991;66:1105–1119. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90034-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter EM, Goddard JM, Chisaka O, Manley NR, Capecchi MR. Loss of Hox-A1 (Hox-1.6) function results in the reorganization of the murine hindbrain. Development. 1993;118:1063–1075. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chisaka O, Musci TS, Capecchi MR. Developmental defects of the ear, cranial nerves and hindbrain resulting from targeted disruption of the mouse homeobox gene Hox-1.6. Nature. 1992;355:516–520. doi: 10.1038/355516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolle P, Lufkin T, Krumlauf R, Mark M, Duboule D, Chambon P. Local alterations of Krox-20 and Hox gene expression in the hindbrain suggest lack of rhombomeres 4 and 5 in homozygote null Hoxa-1 (Hox-1.6) mutant embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7666–7670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosley TM, Alorainy IA, Salih MA, Aldhalaan HM, Abu-Amero KK, Oystreck DT, Tischfield MA, Engle EC, Erickson RP. The clinical spectrum of homozygous HoxA1 mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1235–1240. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosley TM, Salih MA, Alorainy IA, Oystreck DT, Nester M, Abu-Amero KK, Tischfield MA, Engle EC. Clinical characterization of the HoxA1 syndrome BSAS variant. Neurology. 2007;69:1245–1253. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000276947.59704.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tischfield MA, Bosley TM, Salih MA, Alorainy IA, Sener EC, Nester MJ, Oystreck DT, Chan WM, Andrews C, Erickson RP, Engle EC. Homozygous HoxA1 mutations disrupt human brainstem, inner ear, cardiovascular and cognitive development. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1035–1037. doi: 10.1038/ng1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chouinard S, Kaufman TC. Control of expression of the homeotic labial (lab) locus of Drosophila melanogaster: Evidence for both positive and negative autogenous regulation. Development. 1991;113:1267–1280. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reuter R, Panganiban GE, Hoffmann FM, Scott MP. Homeotic genes regulate the spatial expression of putative growth factors in the visceral mesoderm of Drosophila embryos. Development. 1990;110:1031–1040. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Immergluck K, Lawrence PA, Bienz M. Induction across germ layers in Drosophila mediated by a genetic cascade. Cell. 1990;62:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90364-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tremml G, Bienz M. Induction of labial expression in the Drosophila endoderm: response elements for Dpp signalling and for autoregulation. Development. 1992;116:447–456. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panganiban GE, Reuter R, Scott MP, Hoffmann FM. A Drosophila growth factor homolog, decapentaplegic, regulates homeotic gene expression within and across germ layers during midgut morphogenesis. Development. 1990;110:1041–1050. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Ceballos E, Chambon P, Gudas LJ. Differences in gene expression between wild-type and HoxA1 knockout embryonic stem cells after retinoic acid treatment or leukemia inhibitory factor removal. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16484–16498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Ceballos E, Gudas LJ. HoxA1 is required for the retinoic acid-induced differentiation of embryonic stem cells into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2809–2819. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy P, Hill RE. Expression of the mouse labial-like homeobox-containing genes, Hox-2.9 and Hox-1.6, during segmentation of the hindbrain. Development. 1991;111:61–74. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rane SG, Lee JH, Lin HM. Transforming growth factor-β pathway: role in pancreas development and pancreatic disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truty MJ, Urrutia R. Basics of TGF-β and pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2007;7:423–435. doi: 10.1159/000108959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine EM, Schechter N. Homeobox genes are expressed in the retina and brain of adult goldfish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2729–2733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebelein B, Mesa K, Urrutia R. A novel profile of expressed sequence tags for zinc finger encoding genes from the poorly differentiated exocrine pancreatic cell line AR4IP. Cancer Lett. 1996;105:225–231. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook TA, Urrutia R, McNiven MA. Identification of dynamin-2, an isoform ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:644–648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chariot A, Castronovo V. Detection of HoxA1 expression in human breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;222:292–297. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook TA, Mesa KJ, Gebelein BA, Urrutia RA. Upregulation of dynamin II expression during the acquisition of a mature pancreatic acinar cell phenotype. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:1373–1378. doi: 10.1177/44.12.8985129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lomberk G, Bensi D, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Urrutia R. Evidence for the existence of an HP1-mediated subcode within the histone code. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:407–415. doi: 10.1038/ncb1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Kim HJ, Marshall H, Gendron-Maguire M, Lucas DA, Baron A, Gudas LJ, Gridley T, Krumlauf R, Grippo JF. Ectopic Hoxa-1 induces rhombomere transformation in mouse hindbrain. Development. 1994;120:2431–2442. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez CC, Gudas LJ. The truncated HoxA1 protein interacts with HoxA1 and Pbx1 in stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106:427–443. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Studer M, Gavalas A, Marshall H, Ariza-McNaughton L, Rijli FM, Chambon P, Krumlauf R. Genetic interactions between HoxA1 and HoxB1 reveal new roles in regulation of early hindbrain patterning. Development. 1998;125:1025–1036. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaRosa GJ, Gudas LJ. Early retinoic acid-induced F9 teratocarcinoma stem cell gene ERA-1: alternate splicing creates transcripts for a homeobox-containing protein and one lacking the homeobox. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3906–3917. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Githens S, Schexnayder JA, Moses RL, Denning GM, Smith JJ, Frazier ML. Mouse pancreatic acinar/ductular tissue gives rise to epithelial cultures that are morphologically, biochemically, and functionally indistinguishable from interlobular duct cell cultures. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1994;30A:622–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02631262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadowski I. Uses for GAL4 expression in mammalian cells. Genet Eng (NY) 1995;17:119–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellenrieder V, Fernandez Zapico ME, Urrutia R. TGFβ-mediated signaling and transcriptional regulation in pancreatic development and cancer. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2001;17:434–440. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mark M, Lufkin T, Dolle P, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Chambon P. Roles of Hox genes: what we have learnt from gain of function and loss of function mutations in the mouse. C R Acad Sci III. 1993;316:995–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baron A, Featherstone MS, Hill RE, Hall A, Galliot B, Duboule D. Hox-1.6: a mouse homeobox-containing gene member of the Hox-1 complex. EMBO J. 1987;6:2977–2986. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimoto S, Araki K, Chisaka O, Araki M, Takagi K, Yamamura K. Analysis of the murine Hoxa-9 CDNA: an alternatively spliced transcript encodes a truncated protein lacking the homeodomain. Gene. 1998;209:77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin MR, Nguyen-Huu MC. Alternatively spliced Hox-1.7 transcripts encode different protein products. DNA Seq. 1990;1:115–124. doi: 10.3109/10425179009016039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen WF, Detmer K, Simonitch-Eason TA, Lawrence HJ, Largman C. Alternative splicing of the Hox-2.2 homeobox gene in human hematopoietic cells and murine embryonic and adult tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:539–545. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright CV, Cho KW, Fritz A, Burglin TR, De Robertis EM. A Xenopus laevis gene encodes both homeobox-containing and homeobox-less transcripts. EMBO J. 1987;6:4083–4094. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dintilhac A, Bihan R, Guerrier D, Deschamps S, Pellerin I. A conserved non-homeodomain HoxA9 isoform interacting with CBP is co-expressed with the ‘typical’ HoxA9 protein during embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]