Abstract

Most nucleases require a divalent cation as a cofactor, usually Mg2+ or Ca2+, and are inhibited by the chelators EDTA and EGTA. We report the existence of a novel nuclease activity, initially identified in the luminal fluids of the mouse male reproductive tract but subsequently found in other tissues, that requires EGTA chelated to calcium to digest DNA. We refer to this unique enzyme as CEAN (Chelated EGTA Activated Nuclease). Using a fraction of vas deferens luminal fluid, plasmid DNA was degraded in the presence of excess Ca2+ (Ca2+:EGTA = 16) or excess EGTA (Ca2+:EGTA = 0.25), but required the presence of both. Higher levels of EGTA (Ca2+:EGTA = 0.10) prevented activity, suggesting that unchelated EGTA may be a competitive inhibitor. The EGTA-Ca2+ activation of CEAN is reversible as removing EGTA-Ca2+ stops ongoing DNA degradation, but adding EGTA-Ca2+ again reactivates the enzyme. This suggests the possibility that CEAN binds directly to EGTA-Ca2+. CEAN has a greater specificity for the chelator than for the divalent cation. Two other chelators, BAPTA and sodium citrate, do not activate CEAN in the presence of cation, but chelated EDTA does. EGTA chelated to other divalent cations such as Mn2+, Zn2+, and Cu2+ activate CEAN, but not Mg2+. The activity is lost upon boiling suggesting that it is a protein. These data suggest that EGTA and EDTA may not always prevent DNA from nuclease damage.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Sperm DNA, chromatin

Introduction

There are several different types of enzymes in the cell that degrade DNA, collectively referred to here as nucleases. They are involved in a host of functions from DNA repair to apoptosis, and are required for proper cell function (Evans and Aguilera, 2003; Widlak and Garrard, 2005). Most of the nucleases so far identified, with few exceptions, such as prokaryotic exonuclease VII (Larrea et al., 2008), and Dnase2a (Evans and Aguilera, 2003; Oshima and Price, 1973), require divalent cations as cofactors for activity, and are inhibited by EDTA and EGTA, which chelate the cation cofactor. The prototypical enzyme of this group is deoxyribonuclease 1 (Dnase1), originally isolated from the bovine pancreas (Sachs, 1905). Dnase1 is a 32 kd protein that requires Ca2+ and/or Mg2+ for activity, and is completely inhibited by EDTA or EGTA (Napirei et al., 2005). Both Dnase1 and Dnase2a are inhibited by Zn2+ (Laskowski, 1971). It has been proposed that the use of metal cations by certain classes of nucleases is required for substrate specificity. Examples of this are in the forms of sequence and structure recognition of nucleases and polymerases, and also the high fidelity of RNA/DNA polymerases (Yang et al., 2006). In many cation dependant enzymes, the first cation is believed to function in the role of nucleophile formation while the second is needed for transition state stabilization.

We have recently found evidence for an apoptotic-like degradation of DNA in mature mouse spermatozoa (Shaman et al., 2006). Upon incubation of spermatozoa with Mn2+, sperm chromatin is first degraded to 50 kb fragments that can be religated with EDTA, a hallmark of reversible Topo2B cleavage (Li et al., 1999). With further incubation, the sperm DNA is more completely degraded in a typical nuclease digestion pattern that is not reversible (Shaman et al., 2006). In later studies focusing on the nuclease step of this sperm DNA degradation, we demonstrated that the sperm nuclease could be activated by pretreatment with EGTA followed by incubation with Ca2+ (Boaz et al., 2008). In this work, we tested the role of EGTA in activating the sperm nuclease.

Results

Nuclease Activity Requires both EGTA and Ca2+

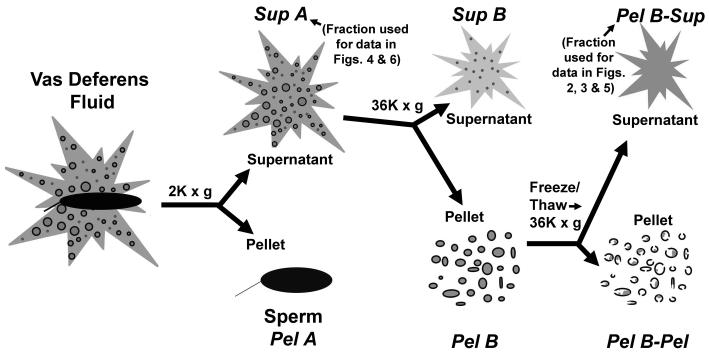

To study the nuclease activity in sperm extracts, we developed a plasmid based assay for DNA degradation (Boaz et al., 2008). A schematic of the isolation of the vas deferens extract used in these studies is shown in Fig 1. The enzymatic activity of the nuclease described below was present in all fractions, but highest in Sup A and Pel B-Sup. Pel B-Pel also contained nuclease activity, but required treatment with the non-ionic detergent to release it (data not shown). This is consistent with our previous report that the sperm nuclease was sequestered in small vesicles in the vas deferens fluid surrounding the spermatozoa (Boaz et al., 2008).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the isolation of the sperm nuclear extract used.

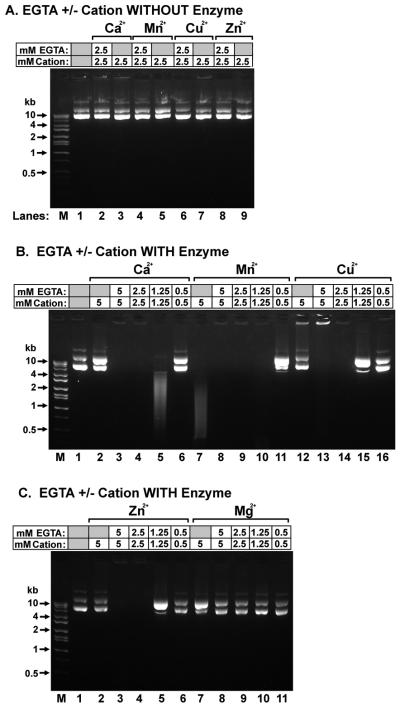

We used a plasmid based assay to determine the role of EGTA in the activation of the nuclease. As a control, we incubated the plasmid with four divalent cations, alone, and with each cation in the presence of EGTA in the absence of tissue extracts. None of these conditions caused DNA degradation (Fig. 2A). We next incubated plasmid DNA with the vas deferens sperm extract (Pel B-Sup) in the presence of varying concentrations of EGTA and divalent cations. We found that Ca2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ or Mg2+, alone, did not activate nuclease activity in the vas deferens extract (Fig. 2B lanes 2 and 12, and Fig. 2C, lanes 2 and 7). Mn+2 alone did activate a nuclease activity in the extract (Fig. 2B, lane 7). We cannot yet establish whether this activity is the same nuclease that requires both EGTA and Ca2+ or a different nuclease in the extract. Therefore, for the rest of the work we used Ca2+ as the divalent cation, which exhibited no activity alone. The nuclease activity that required EGTA and Ca2+ disappeared when the extract was boiled, suggesting the activity depends on a protein.

Figure 2. Nuclease activity requires both EGTA and a divalent cation.

(A) Plasmid DNA was incubated with 2.5 mM Ca2+, Mn2+, Cu2+, or Zn2+, with or without 2.5 mM EGTA, as indicated, without vas deferens extract, for 1 hr at 37°C. (B and C) Plasmid DNA was incubated with vas deferens extract (Pel B Sup) in the presence of varying concentrations of EGTA and divalent cation for 1 hr at 37°C, as indicated. In all figures, grey boxes indicate that EGTA or the cation was not added to the sample. Lane M contains molecular weight markers.

When the plasmid was incubated in the presence of both EGTA and either Ca2+, Zn2+, or Cu2+ the plasmid was digested (Figs. 2B and C). For all combinations, the lowest concentration of chelators and cation was 2.5 mM, although Ca2+ exhibited some activity at 1.25 mM. For these cations, the nuclease activity depended on the presence of both the chelators and the cation. Mg2+, one of the most common cofactors for nucleases, did not activate the nuclease either by itself or in the presence of EGTA (Fig. 2C, lanes 7 – 11). These data indicated that the nuclease activity required the presence of both EGTA and a divalent cation.

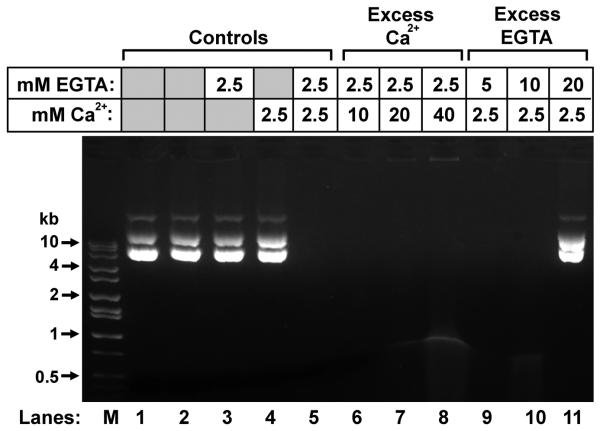

The Nuclease Activity Requires EGTA Chelated to Ca2+

The fact that the nuclease activity required the presence of both EGTA and Ca2+ suggested the possibility that it was the chelated complex that activated the enzyme. Furthermore, because EGTA and Ca2+ alone did not degrade DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 2) but required the presence of the sperm deferens extract (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 - 6), it was probable that both chemicals activated the enzyme. We tested this by incubating the vas deferens Pel B-Sup with varying combinations of EGTA and Ca2+. EGTA chelates Ca2+ in a 1:1 ratio under normal conditions (Miller and Smith, 1984). One possible mechanism by which EGTA might activate the nuclease was that EGTA was removing an inhibitory cation which then allowed Ca2+ to bind to the nuclease. To control for this possibility, we tested the nuclease activity in concentrations of Ca2+ that were up to 16 fold excess of the EGTA (Fig. 3, lanes 6 - 8). Under these conditions, all the EGTA would be expected to be saturated in the chelated form. We found that with excess Ca2+, the enzyme was still active, suggesting that EGTA was not removing an inhibitory cation. We also found that the enzyme was active when the extract was incubated in the presence of excess EGTA (Fig. 3, lanes 9 and 10). Under these conditions, there is no free Ca2+, suggesting that free Ca2+ was not activating the enzyme. The enzyme was inhibited by an 8 fold excess of unchelated EGTA to chelated EGTA (Fig. 3, lane 11) suggesting that when free EGTA is present in high enough concentrations it may compete with chelated EGTA to inhibit nuclease activity.

Figure 3. Nuclease activity requires Ca2+ chelated to EGTA.

Plasmid DNA was incubated with vas deferens extract with varying concentrations of EGTA and Ca2+, as indicated. Lane 1 is a control with no vas deferens extract, and lane 2 is a control with extract (Pel B Sup), but no EGTA or Ca2+. Lanes 3 and 4 contain extract and EGTA or Ca2+, but not both. Lane M contains molecular weight markers. Grey boxes indicate that EGTA or the cation was not added to the sample.

These experiments suggest that the nuclease requires chelated EGTA for activity, and does not require free Ca2+. We therefore term this nuclease CEAN, for Chelated EGTA Activated Nuclease.

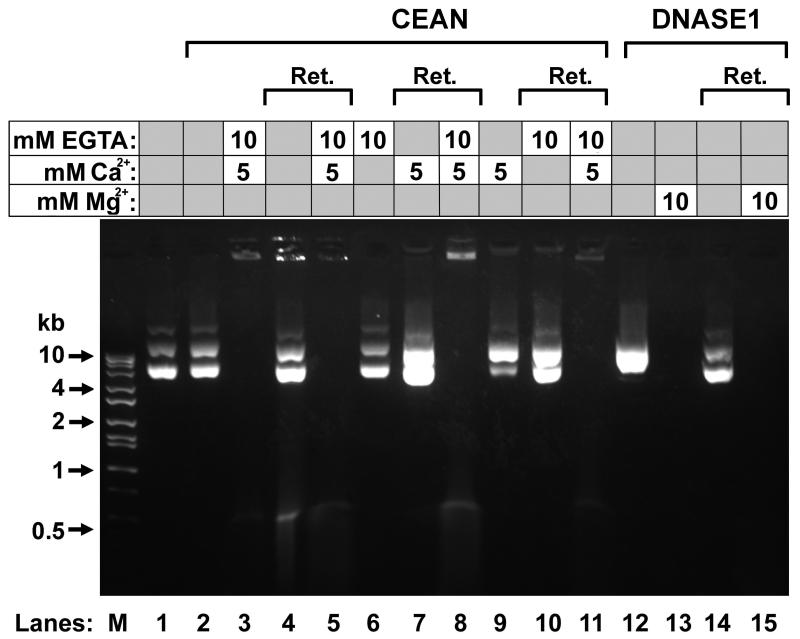

EGTA-Ca2+ Activation of CEAN is Reversible

To further test the role of EGTA in activating CEAN, we next tested whether EGTA-Ca2+ activation of CEAN was reversible. If EGTA-Ca2+ activation of CEAN was irreversible, it might suggest that the chelator initiates a signal pathway that results in enzymatic activation that may include phosphorylation or defined proteolytic degradation. However, if the EGTA-Ca2+ activation was reversible, it would be more likely that the chelator acted as a direct cofactor. To test this, the vas deferens extract Sup B was incubated with EGTA, Ca2+ and plasmid DNA, and then centrifuged in a microtube containing a 10 kd filter to remove the EGTA-Ca2+ from the enzyme. The less pure Sup B fraction was used because the larger total amount of CEAN activity that was present was needed for spin columns. The retentate was then resuspended in buffer without EGTA or Ca2+ and tested for nuclease activity. As shown in Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4, the CEAN digested the DNA before centrifugation but stopped when EGTA-Ca2+ was removed. When EGTA-Ca2+ was added back to the reaction, the nuclease digestion again proceeded (Fig. 4, lane 5). Adding EGTA only or Ca2+ only to the vas deferens extract, and then adding Ca2+ or EGTA, respectively, after centrifugation also failed to activate the nuclease (Fig. 4, lanes 6, 7, 9 and 10), and only when both EGTA and Ca2+, together, were added did the reaction proceed (Fig. 4, lanes 8 and 11). As a control, we performed the same experiment with purified Dnase1 and Mg2+, and demonstrated that removing the Mg2+ from the buffer inhibited the activity, but adding Mg2+ back reactivated the nuclease (Fig. 4, lanes 12-15). These data support the hypothesis that Ca2+ chelated to EGTA binds directly to the CEAN as a cofactor.

Figure 4. Removal of EGTA-Ca2+ from the nuclease reaction by size filtration centriguation.

Lane 1, control with plasmid DNA, only. Lane 2, control with vas deferens extract (Sup B) and plasmid DNA with no EGTA or Ca2+. Lane 3, vas deferens extract incubated with EGTA and Ca2+ and plasmid DNA for 1 hr at 37°C, showing DNA digestion. Lane 4, the extract (Sup B) from lane 3 was centrifuged through a 10 kd filter, and the retentate resuspended in buffer containing additional plasmid DNA, and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Lane 5, EGTA and Ca2+ was added to the suspension in lane 4 and then incubated for an additional 1 hr at 37°C. Lane 6, vas deferens extract (Sup B) incubated with EGTA and plasmid DNA for 1 hr at 37°C, showing DNA digestion. Lane 7, the extract from lane 6 was centrifuged through a 10 kd filter, and the retentate resuspended in buffer containing additional plasmid DNA and Ca2+, and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Lane 8, EGTA was added to the suspension in lane 7 and then incubated for an additional 1 hr at 37°C. Lanes 9 – 11, as for lanes 6 – 8, but with EGTA and Ca2+ reversed. Lane 12, Dnase1 incubated with plasmid DNA for 1 hr at 37°C. Lane 13, Mg2+ added to the suspension in lane 12 and incubated for another hour at 37°C, now showing DNA digestion. Lane 14, the suspension from lane 13 was centrifuged through a 10 kd filter, and the retentate resuspended in buffer containing additional plasmid DNA, and incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Lane 15, Mg2+ was added to the suspension in lane 14 and then incubated for an additional 1 hr at 37°C. Lane M contains molecular weight markers. Grey boxes indicate that EGTA or the cation was not added to the sample.

Enzyme is specific for EGTA/EDTA

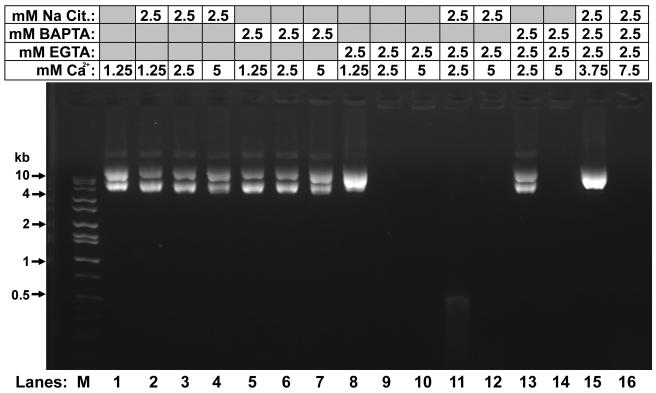

We next tested the specificity of CEAN for the chelator. 1,2-bis-(o-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) is a stronger Ca2+ chelator than EGTA, but has a similar chemical structure to EGTA differing only by the addition of two aromatic rings (Tsien, 1980). Citrate is another Ca2+ chelator with a very different chemical structure to EGTA. We found that neither BAPTA nor citrate were able activate CEAN in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 5, lanes 2-7). BAPTA did not inhibit plasmid digestion by CEAN in the presence of EGTA and Ca2+ (Fig. 5, lane 14). However, the data do suggest that BAPTA does chelate Ca2+ in this experiment and may even compete with EGTA. When 2.5 mM, each, of EGTA, BAPTA and Ca2+ were incubated with vas deferens extract the nuclease was inhibited (Fig. 5, lane 13). In this experiment, we would expect BAPTA to compete with EGTA for chelating Ca2+, thereby decreasing the total level of EGTA-Ca2+ to less than 2.5 mM, the point where CEAN is not activated (Fig. 5, lanes 8 and 9). This conclusion is supported by the restoration of CEAN activity when the Ca2+ concentration in this experiment was increased to 5 mM (Fig. 5, lane 14). In that experiment, both EGTA and BAPTA would be expected to be saturated with Ca2+, providing the 2.5 mM EGTA-Ca2+ required for full activity (Fig. 5, lane 9).

Figure 5. CEAN is specific for EGTA.

Plasmid DNA was incubated with vas deferens extract (Pel B Sup) in the presence of varying concentrations of EGTA, BAPTA, citrate, and Ca2+, as indicated, for 1 hr at 37°C. Lane M contains molecular weight markers. Grey boxes indicate that EGTA or the cation was not added to the sample.

These data suggest that it is not simply the chelation of Ca2+ that activates CEAN, but that the enzyme has some specificity to the chelator, itself, EGTA complexed to Ca2+.

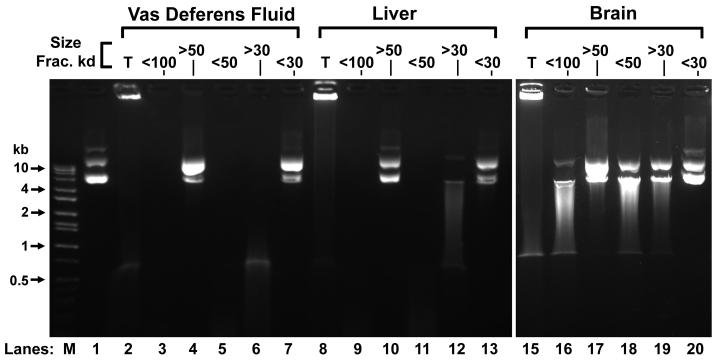

CEAN is Present in Several Other Tissues

The novelty of a nuclease that is activated by Ca2+ chelated to EGTA in the sperm vas deferens fluid prompted us to examine other tissues for the presence of similar activity. We prepared crude extracts from mouse liver and brain, as described in Methods. We then fractionated the vas deferens, liver and brain extracts using spin columns with different size filters, and tested each for CEAN activity. We found that for both the vas deferens and liver extracts, the CEAN nuclease activity was in the <50 kd and >30 kd fractions (Fig. 6, lanes 5, 6, 11 and 12). We found no activity for a CEAN like nuclease in the brain. While this method cannot establish the molecular weight of CEAN, it does suggest that the activities in the two tissues do fractionate the same way in size filtration columns. We also tested several other tissues including heart, intestine, stomach, spleen, and kidney and found that in all these tissues, nuclease activity that required EGTA chelated to Ca2+ was present (data not shown). This suggests that CEAN is not restricted to the male reproductive tract, but may be a more ubiquitous enzyme.

Figure 6. CEAN activity is present in liver, and is a protein between 50 and 30 kd.

Vas deferens (lanes 2-7, Sup B), liver (lanes 8-13), and brain (lanes 15-20) extracts were fractionated into different size fractions using size filter centrifugation tubes. Lanes 2, 8 and 15, total extracts. Lanes 3, 9, and 16, 100 kd eluents. Lanes 4, 10, and 17, 50 kd retentates. Lanes 5, 11, and 18, 50 kd eluents. Lanes 6, 12, and 19, 30 kd retentates. Lanes 7, 13, and 20, 30 kd eluents. All extracts were incubated with plasmid DNA, 5 mM EGTA and 2.5 mM Ca2+ for 4 hrs at 37°C. Lane M contains molecular weight markers. Grey boxes indicate that EGTA or the cation was not added to the sample.

Discussion

When we first described the existence of a nuclease activity in mouse sperm fluids that could be activated by pretreatment with EGTA and subsequent incubation with Ca2+, we proposed two possible models to explain the role of EGTA in the nuclease activation (Boaz et al., 2008). One possibility was that EGTA initiated an activation reaction, perhaps by releasing a calmodulin like protein from inhibiting the nuclease, which then required Ca2+ as a cofactor. The data presented here suggest that this hypothesis is incorrect for two reasons. First, the activation by EGTA-Ca2+ is reversible, suggesting that activation by EGTA is not the result of a complicated cell signaling pathway. Second, the data clearly suggest that it is the chelated form of EGTA-Ca2+ that activates the nuclease (Fig. 3). This means that it cannot be a sequential reaction in which EGTA has one function, and Ca2+ has another.

The second possible model to explain EGTA activation of CEAN was that EGTA chelated an inhibitory cation and Ca2+ then served as the cofactor of the nuclease. But our data do not support this model, either. Fig. 3, lanes 6 – 8, in particular, indicate that CEAN is activated in a large excess of Ca2+ in the presence of EGTA. Under these conditions, EGTA would be expected to be saturated by Ca2+ and would not be expected to be available for chelation of another cation. Additionally, Zn2+, which is a typical inhibitory cation for many nucleases activates, rather than inhibits, CEAN (Fig. 2C).

Our data support a model in which the nuclease directly binds to the EGTA-Ca2+ complex. We were unable to find another report of a nuclease that is activated by chelated EGTA. The fact that it is also present in the liver, spleen, heart, kidney, stomach and intestine suggests that it is not limited to the male reproductive tract, and may represent a novel class of nuclease not previously described. We propose that the natural cofactor of CEAN is a EGTA like molecule. One candidate is γ-carboxyglutamic acid, a posttranslational amino acid modification that can chelate Ca2+ (Vermeer, 1984). The interaction between matrix Gla protein (MGP) and BMP-4 is facilitated by Ca2+ chelation of γ-carboxyglutamic acid residues on MGP (Yao et al., 2008). It is possible that CEAN is activated by a similar protein-protein interaction.

We are currently attempting to isolate CEAN to test the role of EGTA activation of this nuclease more specifically. This is the first report of a nuclease that is activated by chelated EGTA. It suggests that a novel, previously undefined, class of nuclease exists. Based on our previous report (Boaz et al., 2008), it is possible that CEAN functions in the apoptotic degradation of cell chromatin. While much more work is remains before these findings are definitive, the data clearly demonstrated the existence of a novel nuclease activity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male B6D2F1 (C57BL/6J × DBA/2) mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Raleigh, NC). Mice were fed ad libitum and kept in standard housing in accordance with the guidelines of the Laboratory Animal Services at the University of Hawaii and those prepared by the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Resources National Research Council (DHEF publication no. [NIH] 80-23, revised 1985). The protocol for animal handling and the treatment procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Hawaii.

Preparation of Extracts

For extracts from the vas deferens or epididymus, mice were sacrificed using carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. A schematic diagram for the isolation of the vas deferens extract is shown in Fig. 1. The epididymis and/or vas deferens were excised and fluid from the epididymis and/or vas deferens gently extracted, using tweezers, and diluted to a concentration of approximately 108 spermatozoa/ml in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl buffer (TKB) and kept on ice. Extracted fluid from the epididymis and/or vas deferens was centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 2 minutes at room temperature. This gave rise to a pellet consisting of sperm cells, which was reconstituted in TKB. The resulting supernatant, Sup A, was centrifuged at 36,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4° C giving rise to two subfractions, the supernatant, Sup B, and pellet, Pel B. Sup B was used for the size fractionation experiments for which large amounts of enzyme were required (Figs. 4 and 6). The Pel B, thought to contain vesicles, was reconstituted in TKB, frozen at −80° C, then thawed to disrupt vesicle membranes then centrifuged again at 36,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4° C, giving rise to the supernatant, designated Pel B-Sup, and pellet, designated Pel B-Pel. Pel B-Sup was the fraction with the highest concentration of CEAN activity, and used for experiments that characterized the activity of CEAN (Figs 2, 3 and 5).

For extracts from the liver and brain, mice were sacrificed as above, and the liver or brain were excised separately. Each were homogenized in 0.5% TX in a homogenizer, centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes, then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants of both were analyzed for activity.

Size fractionation of Extracts

Samples were further fractionated according to size using Vivaspin 500 spin-tubes. Approximately 300 μl of sample was centrifuged through a 100, 50, 30, 10, or 5 kDa filter at 13,000 × g for between 10 to 40 minutes at 4°C. In order to clean the retentates, they were resuspended with approximately 500μl TKB and centrifuged three times until eluent fully removed from retentate. Retentate then resuspended in 300μl TKB.

Nuclease Assay

Plasmids for the nuclease assay were prepared using a CompactPrep Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen, Catalog Number 12743). Midi Kit Plasmid procedure was followed resulting in the harvest of purified plasmid DNA (0.51 μg/μl). Nuclease activity was activated by incubating approximately 3 μl of one of the various sperm, liver or brain preparations described above in a total of 20 μl of TKB with 0.624 μg plasmid DNA supplemented with divalent cations (Mn2+, Ca2+, Zn2+, or Cu2+) and/or EGTA. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes to 2 hours. Cation and EGTA concentrations varied from 2.5 mM to 50 mM in TKB. Evidence of activity was measured by visual detection of digested plasmid DNA separated by electrophoresis on 0.05% ethidium bromide 1% agarose gel.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Dr. Joeseph Jarrett, of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Hawaii at Manoa for helpful discussion on EGTA chelation chemistry. We would also like to than Dr. Geoffry De Iuliis of the ARC Centre of Excellence in Biotechnology & Development at University of Newcastle, for helpful discussions on free radical chemistry.

References

- Boaz SM, Dominguez KM, Shaman JA, Ward WS. Mouse Spermatozoa Contain a Nuclease that Is Activated by Pretreatment with EGTA and Subsequent Calcium Incubation. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1636–1645. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans CJ, Aguilera RJ. DNase II: genes, enzymes and function. Gene. 2003;322:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrea AA, Pedroso IM, Malhotra A, Myers RS. Identification of two conserved aspartic acid residues required for DNA digestion by a novel thermophilic Exonuclease VII in Thermotoga maritima. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5992–6003. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski M. Deoxyribonuclease I. In: Boyer PD, Landy H, Myrback K, editors. The Enzymes. Academic Press; New York: 1971. pp. 289–311. [Google Scholar]

- Li TK, Chen AY, Yu C, Mao Y, Wang H, Liu LF. Activation of topoisomerase II-mediated excision of chromosomal DNA loops during oxidative stress. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1553–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Smith GL. EGTA purity and the buffering of calcium ions in physiological solutions. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:C160–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.1.C160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napirei M, Wulf S, Eulitz D, Mannherz HG, Kloeckl T. Comparative characterization of rat deoxyribonuclease 1 (Dnase1) and murine deoxyribonuclease 1-like 3 (Dnase1l3) Biochem J. 2005;389:355–64. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima RG, Price PA. Alkylation of an essential histidine residue in porcine spleen deoxyribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:7522–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F. Ober die Nuclease. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 1905;46:337–353. [Google Scholar]

- Shaman JA, Prisztoka R, Ward WS. Topoisomerase IIB and an Extracellular Nuclease Interact to Digest Sperm DNA in an Apoptotic-Like Manner. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:741–748. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.055178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: design, synthesis, and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2396–404. doi: 10.1021/bi00552a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer C. The binding of Gla-containing proteins to phospholipids. FEBS Lett. 1984;173:169–72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)81040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widlak P, Garrard WT. Discovery, regulation, and action of the major apoptotic nucleases DFF40/CAD and endonuclease G. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:1078–1087. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Lee JY, Nowotny M. Making and breaking nucleic acids: two-Mg2+-ion catalysis and substrate specificity. Mol Cell. 2006;22:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Shahbazian A, Bostrom KI. Proline and gamma-carboxylated glutamate residues in matrix Gla protein are critical for binding of bone morphogenetic protein-4. Circ Res. 2008;102:1065–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.166124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]