Abstract

Background

Chronic rotator cuff tears are often associated with pain or poor function. In a rat with only a detached supraspinatus tendon, the tendon heals spontaneously which is inconsistent with how tears are believed to heal in humans.

Questions/purposes

We therefore asked whether a combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus detachment in the rat would fail to heal and result in a chronic injury in the supraspinatus tendon.

Methods

We acutely detached the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons in a rat model. At 4, 8, and 16 weeks post-detachment, biomechanical testing, collagen organization, and histological grading were evaluated for the detached supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons and compared to controls.

Results

In the detached supraspinatus tendon, area and percent relaxation were increased at all time points while the modulus and stiffness were similar to those of controls at 4 and 8 weeks. Collagen disorganization increased at late time points while cellularity increased and cells were more rounded in shape. In the detached infraspinatus tendon, area and percent relaxation were also increased at late time points. However, the modulus values initially decreased followed by an increase in both modulus and stiffness at 16 weeks compared to control. In the detached infraspinatus, we also observed a decrease in collagen organization at all time points and increased cellularity and a more rounded cell shape.

Conclusions

Due to the ongoing changes in mechanics, collagen organization and histology in the detached supraspinatus tendon compared to control animals at 16 weeks, this model may be useful for understanding the human chronic tendon tear.

Clinical Relevance

This rat rotator cuff chronic model can be used to test hypotheses regarding injury and repair mechanisms that cannot be addressed in human patients or in cadaveric studies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11999-009-1206-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Rotator cuff tears are a common source of pain and disability. Chronic tendon tears generally involve multiple tendons of the rotator cuff and are considered more difficult to repair than acute tears. They are often associated with inferior surgical outcomes that may be attributed to the altered quality of the tendon post injury [12, 17]. Many clinical studies have attempted to elucidate the relationship between surgical outcome and time post tear (as measured by duration of symptoms) with some studies recommending a short [3], others a long trial [5] of nonoperative treatment before surgery while still others suggest no correlation between duration of symptoms and relief of symptoms with surgery [6]. This is often due to the difficulty in determining the actual length of time the tear was present. Structural and compositional changes associated with chronic tendon tears have been studied in several clinical studies using biopsy specimens of the supraspinatus tendon stump or cadaveric tissue. Previous studies demonstrate an increase in cellularity, vascularity, and disorganized scar tissue at the end of the tendon stump [11, 15, 16]. However, since many of these specimens are taken at time of surgery, tissue biopsies are often restricted to the portion of the tendon removed during surgical repair and the remaining tendon cannot be investigated. Although clinical studies provide valuable information, an animal model would be helpful to evaluate specific hypotheses regarding changes in tendon mechanics and morphology post injury with time as these hypotheses cannot be addressed in human patients, yet require an in vivo system to evaluate changes. We believe this information important for fundamental understanding of disease progress and for the possibility of evaluating potential treatment modalities. We previously suggested the rat as an appropriate animal model for human rotator cuff disease due to the similarity to the human in shoulder bony anatomy and supraspinatus excursion [25].

In another of our studies in the rat we attempted to create a chronic injury with a single supraspinatus detachment without repair [14]. Organizational and mechanical properties were measured over time and overall the properties initially decreased, but by 16 weeks the injury in the detached supraspinatus had recovered. In another study we measured rat ambulation with either a single supraspinatus only detachment or a combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus detachment [22]. By 8 weeks in the supraspinatus only detachment group, most ambulatory parameters had recovered. However, in the combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus detachment group, many ambulatory parameters were still altered from control. This suggests that with respect to larger tendon injuries, glenohumeral kinematics did not recover at the longest time points.

Therefore, we first asked whether a combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus detachment could result in a chronic injury in the supraspinatus tendon based on tissue level properties. We then hypothesized that after a combined two tendon detachment, the detached supraspinatus tendon would have decreased mechanical properties compared to control up to 16 weeks as well as continued degenerative histological changes consistent with a chronic condition. Finally, we hypothesized the detached infraspinatus tendon’s mechanical and histological properties would remain inferior to control at all time points.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and three Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved study. The rat was chosen based on a previous study that evaluated animals according to a 34 item checklist of criteria to determine their appropriateness as an animal model for investigations on the rotator cuff [25]. The rat was the only nonprimate that satisfactorily fulfilled all criteria, with a prominent supraspinatus tendon passing under an enclosed arch. Two previous studies reported the tissue from a 2×2 mm midsubstance tendon defect is inferior to control at 12 weeks in both histologic evaluation and biomechanical properties [7, 27]. This suggests small tendon defects do not heal over time and that when compared to control, tendon injury in the rat model is discriminatory enough to detect substantial differences in biomechanics, collagen organization and histologic evaluation even though the injuries can be small in absolute size. Although the increase in scar formation seen in rats compared to humans can be a complicating factor as seen in the spontaneous healing of the single tendon detachment discussed previously [14], this is true of all animal models including large ones [8, 13, 20]. Therefore, the rat was chosen as an appropriate animal model to evaluate the formation of a chronic tendon injury using a two tendon detachment approach.

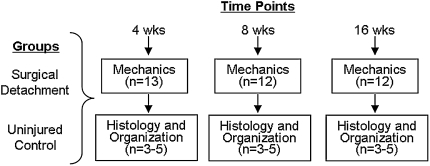

We divided animals into either a surgical group (n = 51) or a time matched control group (n = 52) (Fig. 1). Rats in the surgical group underwent a unilateral surgery to sharply detach the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons from the bony insertion as described below. The remaining uninjured animals were allowed cage activity and served as time-matched controls. At 4, 8, and 16 weeks, we sacrificed the animals and evaluated biomechanical and geometric properties, histological degeneration and collagen organization. Using data from a previous study [14], an a priori power analysis with an error probability of 0.05 and power of 0.8, indicated that a minimum sample size of 11 animals for mechanics and three animals for polarized light collagen organization analysis was necessary.

Fig. 1.

The study design is shown as a graph.

Animals in the surgical group underwent a unilateral combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon detachment similar to that described previously [21]. Briefly, with the arm in external rotation, a 2-cm incision was made over the scapulohumeral joint followed by blunt dissection down to the rotator cuff musculature. The supraspinatus tendon was visualized as it passed under the bony arch comprised of the acromion, coracoid, and clavicle as well as the infraspinatus, posterior to the supraspinatus and with a similar insertion. Suture was passed under the acromion to apply upward traction for further exposure, and the supraspinatus was separated from the other tendons before sharply detaching it at its insertion on the greater tuberosity. A marking suture (5-0 prolene) with long tails was placed at the end of the tendon to facilitate retrieval at the time of dissection. In a similar fashion, the infraspinatus tendon was detached from its bony insertion and marked with suture. Detached tendons were allowed to retract freely creating a gap ~4 mm from their insertion sites. The overlying muscle and skin were closed, and the rats were allowed unrestricted cage activity. Animals were sacrificed at 4 weeks (n = 17), 8 weeks (n = 17), and 16 weeks (n = 17) post detachment. The remaining 52 animals were prescribed cage activity only (no surgery) and were used as time matched controls at 4 weeks (n = 18), 8 weeks (n = 17), and 16 weeks (n = 17).

For biomechanical and geometric analysis at each time point, the detached supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle-tendon units were dissected out using the marking suture to identify the detached tendon insertion sites. At dissection, marking sutures identifying the tendon insertion site on the detached supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons were easily identified. Some scar formation was observed between the detached tendon ends and bony insertion sites but was removed based on the location of the marking sutures. The muscle was removed and the tendons were finely dissected under a microscope. During this fine dissection, gross scar tissue located near the tendon was carefully removed by an experienced investigator in a consistent and blinded fashion. Briefly, the tendon ends were manually gripped and a minimal amount of load was applied manually. Tissue that was visualized to move but not stretch or deform under load was considered non-load bearing tissue and was removed. Any tissue that stretched under load, and therefore bore load, remained.

A total of 12 to 13 animals were used for biomechanical testing. Verhoeff stain lines were then placed along the length of the tendon for optical strain analysis. Tendon cross-sectional area was measured at the location of local strain measurement using a laser-based system [10, 21]. For biomechanical testing, the tendon was gripped using fine grit sandpaper and placed into screw clamps resulting in a gauge length of 7 mm. The specimen was immersed in a 39°C PBS bath, preloaded to 0.01 N, preconditioned for 10 cycles from 0.01 N to 0.05 N at a rate of 1%/s, and held for 300 sec. Immediately following the 300-sec hold, a stress relaxation experiment was performed by elongating the specimen to a strain of 6% at a rate of 50%/sec (3.5 mm/sec) followed by a 600-sec relaxation period. Following the 600-sec relaxation period, a ramp to failure test was applied at a rate of 0.3%/sec (0.021 mm/sec). Using the applied stain lines, local tissue strain was measured optically with a custom program (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA). Elastic properties, such as stiffness and modulus, were calculated using linear regression from the near-linear region of the load-displacement and stress-strain curves, respectively. As measures of viscoelastic properties, peak and equilibrium load were determined from the stress relaxation curve for each specimen and used to calculate percent relaxation.

For histological and organizational analysis at each time point, for both the detached supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle-tendon units, 5-μm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Three to five sections per group were evaluated based on section quality. H&E sections were used to assess cellularity and cell shape as well as to measure collagen organization. Cellularity and cell shape analysis was performed in a semiquantitative manner by assigning a rank to each of the observations where 0 indicates normal, 1 indicates mild changes, 2 indicates moderate changes, and 3 indicates marked changes (changes to an increase in cellularity and more rounded, rather than spindle-shaped cells) [26]. Analysis was performed independently by three blinded graders who were provided with previously prepared standard images representing each grading level for each measure to provide consistency (supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR). The interobserver variability reflected by Fleiss kappa values was as follows: supraspinatus cellularity 0.52, supraspinatus cell shape 0.45, infraspinatus cellularity 0.46, and infraspinatus cell shape 0.46 (Cardillo G. (2007) Fleiss’es kappa: compute the Fleiss’es kappa for multiple raters. http://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/15426. Programmed for Matlab).

In addition, we measured tendon collagen organization using a quantitative, polarized light microscopy as described previously [14]. Briefly, digital images of H&E sections were taken under polarized light at 200× magnification and a quantitative, custom written program (Matlab, MathWorks, Natick, MA) was used to determine fiber direction. The circular angular deviation (AD) of the collagen, a measure of the collagen disorganization, was determined using a circular statistics software package (Oriana, RockWare, Golden, CO).

We determined differences in the biomechanical and geometric properties and polarized light collagen organization analysis between injured animals and time-matched controls using one-tailed t-tests. A one-tailed Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used to compare injured animals and time-matched controls for histological grades.

Results

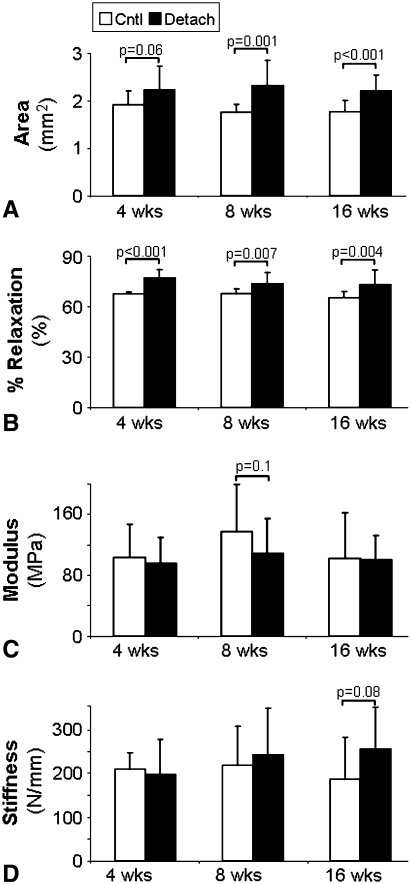

Compared to time-matched controls we observed detrimental changes in the detached supraspinatus tendon properties at both early and late time points. The area was increased by 8 weeks compared to control and remained increased at the 16 week time point (Fig. 2A). Percent relaxation remained increased at all time points (Fig. 2B). The modulus and stiffness of the tendon were similar to those of controls at all time points (Fig. 2C–D).

Fig. 2A–D.

Geometric and biomechanical properties (n = 12–13) of the time-matched controls and detached supraspinatus tendons are shown at each time point (mean and standard deviation). Comparisons are of detached tendons to time matched controls (p < 0.1 shown). Both (A) area and (B) percent relaxation remained increased from time matched controls, even at the 16-week time point. No differences were seen in (C) modulus or (D) stiffness.

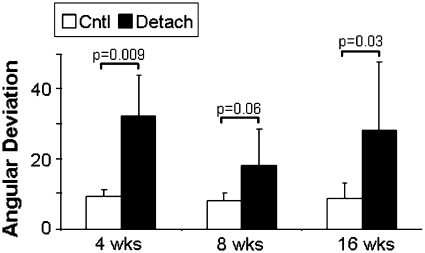

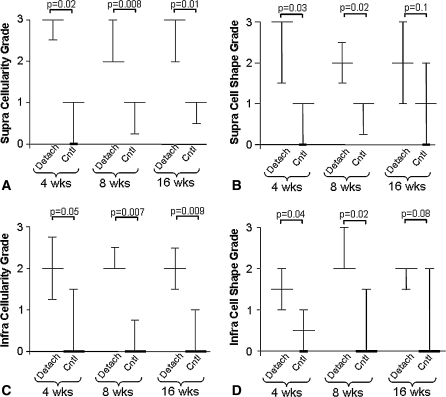

Polarized light analysis of the detached supraspinatus tendon showed an increase in disorganization at 4 and 16 weeks (Fig. 3). Histological grading showed increased cellularity as well as a more rounded cell shape (Fig. 4A–B, Fig. 5A–B). Thus in the detached supraspinatus tendon, some detrimental changes seen at early time points remain at later time points.

Fig. 3.

Collagen angular deviation (n = 3–5) of the time matched controls and detached supraspinatus tendons is shown at each time point (mean and standard deviation). Comparisons are of detached tendons to time matched controls (p < 0.1 shown). Tendon angular deviation remains increased, or decreased organization, even at late time points, suggesting the tendon is not healing.

Fig. 4A–D.

(A) Cellularity and (B) cell shape grades for detached supraspinatus are shown; (C) cellularity and (D) cell shape grades for infraspinatus tendons are shown as median and interquartile range due to the nonparametric nature of the data. Comparisons are of detached tendons to time matched controls. Both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons remain altered from controls.

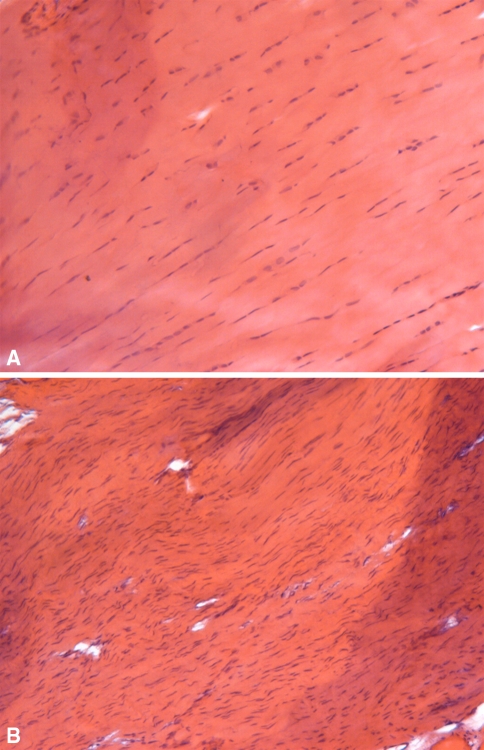

Fig. 5A–B.

Representative supraspinatus H&E samples at 16 weeks (200×) are shown. The 16 week uninjured control (A) shows long, spindle shaped fibroblasts aligned between collagen fibers where the 16 week detached supraspinatus tendon (B) shows increased cellularity, more rounded cells and a random distribution of fibroblasts throughout the ECM.

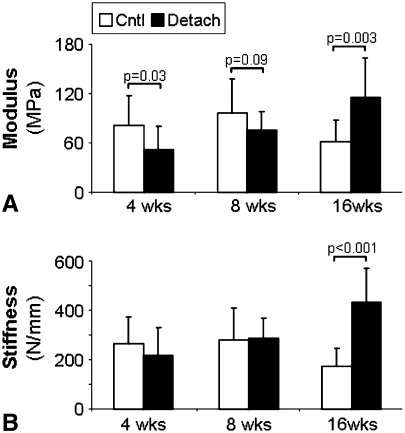

Similar to the findings in the supraspinatus, the area of the detached infraspinatus tendon was increased at 8 and 16 weeks as was the percent relaxation at all time points (Table 1). Properties remained inferior to time matched controls even at 16 weeks, similar to that seen in the detached supraspinatus. However, in the detached infraspinatus tendon, the modulus values initially decreased followed by an increase at 16 weeks as well as an increase in stiffness at 16 weeks (Fig. 6A–B). Organizational and histological analyses showed an increase in collagen disorganization at all time points (Table 1), as well as increased cellularity and a more rounded cell shape (Fig. 4C–D).

Table 1.

Area, percent relaxation and collagen angular deviation of the time matched control and detached infraspinatus tendon at all time points (mean ± SD). Comparisons are between detached tendons and time matched controls

| 4 wk control | 4 wk detach | p-value | 8 wk control | 8 wk detach | p-value | 16 wk control | 16 wk detach | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (mm2) | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 0.009 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 |

| %Relax (%) | 71 ± 4 | 74 ± 8 | 0.2 | 65 ± 5 | 75 ± 5 | < 0.001 | 60 ± 3 | 74 ± 4 | < 0.001 |

| Angular deviation | 10.8 ± 3.1 | 36.5 ± 13.1 | 0.01 | 8.6 ± 5.0 | 26.9 ± 10.6 | 0.008 | 5.3 ± 2.8 | 22.7 ± 10.7 | 0.004 |

Fig. 6A–B.

(A) Modulus and (B) stiffness (n = 12–13) of the time-matched controls and detached infraspinatus tendons are shown at each time point (mean and standard deviation). Comparisons are of detached tendons to time matched controls, p < 0.1 shown. Unlike the supraspinatus tendon, the infraspinatus is seen to have increased modulus and stiffness at the 16 week time point suggesting that the tendon is healing.

Discussion

Chronic rotator cuff tears are often associated with poor surgical outcomes such as continued pain and poor function. Clinical studies cannot determine serial changes in tendon mechanics and morphology with time post-injury. An animal model would provide an in vivo system in which hypotheses regarding disease progression and potential treatment modalities could be evaluated. Although there are no data in the literature due to the limitations in obtaining tissue clinically, it is presumed that the degenerated human tendons observed in chronic injuries will not heal and regain mechanical properties. Owing to limitations in obtaining tissue, changes in morphology and tendon mechanics after injury cannot be addressed in human patients and therefore an animal model would be helpful to explore such hypotheses. Detachment of the sheep infraspinatus tendon [8, 13, 20] has been used to investigate tendon properties in an attempt to create a chronic tear condition, however, the tendon modulus increased as early as 6 weeks post-detachment unlike that which is expected in the human condition. This result is similar to the healing seen in the single detached rat supraspinatus tendon discussed previously in which some mechanical properties and collagen disorganization had returned to control values by 4 weeks [14]. Additional models in the sheep infraspinatus [13, 20], canine infraspinatus [24], and rabbit supraspinatus [4, 9, 18, 23] have also been used to investigate rotator cuff muscle degeneration with an acute tendon detachment, but have not examined tendon properties. A chronic model in the rat would contribute to the understanding of chronic tears due to the unique similarities between the human and rat bony anatomy [25] and the ability to conduct larger scale studies in a more practical manner in this model system. We therefore used an established rat model to investigate the use of a combined two tendon detachment to study the biomechanical, geometric, and histological changes in the detached tendons and to assess whether this approach would yield a chronic, degenerative supraspinatus tendon.

Some potential limitations are associated with this study. First, the rat model of surgically detached tendons is not an exact model for the tears that occur in degenerated human tendons. In the clinical setting, chronic tears form slowly over time where in our model an acute detachment is used to create the injury. We would expect the healing response in a degenerated torn tendon to be less robust than in a healthy detached tendon and therefore have even less capacity to heal. Second, we acknowledge that too small of a defect would not lead to an understanding of the healing process in large defects in the human since generally speaking, small defects heal well while larger defects may not. However, the injury used in this study is sufficiently large to provide value in understanding the healing process as evidenced by the poor healing seen even at 16 weeks as reflected by increased area, percent relaxation, tissue disorganization and altered histology. Indeed, the injury made simply did not heal well. Therefore, we presume this defect, although small in absolute size, is a critical size to be used as a model since it did not appear normal at 16 weeks. Third, we observed scar formation between the bony insertion and the supraspinatus tendon end similar to the repair in large and small animal models [13, 14]. This location of scar formation is believed to be inconsistent with the clinical condition where the cuff has a diminished ability to repair itself, even through scar formation, possibly due to the interactions with joint and bursal fluid [17]. However, our data suggest that in this study the tendon is still experiencing decreased loading resulting in a reproducible injury. Fourth, even at the 16-week time point the tendon properties had not stabilized but may not remain altered at even later time points. However, it is important to note that concepts, and not specific time points, can translate between animal and human studies. Fifth, we did not evaluate a sham surgery. However, in a previous study with a rotator cuff injury in the same model we observed no histologic differences between sham and control [25].

After a two tendon detachment, we observed histological changes consistent with tendon degeneration early in the supraspinatus tendon and these persisted when compared to control. Decreased organization, increased cellularity, and rounded cell shape are all consistent with histopathologic human studies of chronic rotator cuff tears [11, 16]. A clinical study examining full-thickness supraspinatus tendon biopsy specimens found rounding of the cell nuclei and increased cellularity as well as marked collagen disorganization [16]. Changes were seen in the macroscopically intact portion of the tendon suggesting degeneration is not just localized to the ruptured tendon end. Another study examined chronic tendon injuries with respect to tear size and showed in small tears increased cellularity and vascularization presumed to be part of an active reparative process [19]. Conversely, decreased cellularity was noted with a massive tear with no evidence of cell proliferation. Although the length of time the tear was present is unknown, it can be inferred that with time there is a reduction in the potential for healing.

After a two tendon detachment, we found increased area and disorganized collagen in the supraspinatus tendon. This suggests inferior tissue is being synthesized and results in a more viscous mechanical response as described by an increase in percent relaxation. These results are consistent with changes seen in tendon and ligament injury [1, 2] and indicate the detached supraspinatus tendon in our model is in fact injured. Another study showed stress-shielding of patellar tendon resulted in increased percent relaxation, cross-sectional area and increased fibroblast numbers [28]. These results are similar to what we found at all time points in the supraspinatus tendon and indicate the tendon is remaining altered in its unloaded state.

We observed scar formation grossly between the infraspinatus bony insertion and tendon end. Other animal models have seen similar scar formation following acute tendon detachments. In the sheep infraspinatus model, even when the tendon end is wrapped with a nonabsorbable material at time of acute detachment, blunt dissection is still required to mobilize the tendon at later time points [8, 13, 20]. In a sheep infraspinatus tendon study, modulus was seen to increase compared to control at 6 and 18 weeks post-detachment [8], similar to that seen in our detached rat infraspinatus tendon at 16 weeks. For this reason, we speculate that adhesions in our model may have resulted in reloading of the infraspinatus and may help provide an explanation for the pattern seen in the infraspinatus biomechanical properties.

We also observed fibrotic scar tissue between the insertion site and tendon end of the supraspinatus. Although both tendons were detached in the same manner, it is possible the adhesions at the supraspinatus were less well-formed than those between the infraspinatus and its insertion site. This may be due to the unique anatomic location of the supraspinatus in that it is surrounded by the other rotator cuff tendons and the bony acromion. These other structures may provide additional locations for adhesions to form, therefore likely altering the natural loading environment of the supraspinatus.

In developing a chronic tendon detachment model, we would expect to find altered properties in a chronically detached tendon, even at relatively long time points, without the improvement that would be characteristic of healing. In our previous one tendon detachment model, properties did improve over time, providing difficulty in longer term chronic studies. However, in our current two tendon detachment model, changes even at long time points in the detached supraspinatus tendon were seen in some biomechanical characteristics as well as histological and organizational properties. In addition, our previous study [22] suggests functional changes persist with time in this model further supporting its validity. Therefore, this model may serve as a useful tool in studying the chronic tear condition for the supraspinatus tendon as well as for evaluations of potential treatment modalities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH/NIAMS (R01 AR051000) and the NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30 AR050950) for funding this study.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (LMD, SMP, LJS) has received funding from the NIH/NIAMS (R01 AR051000) and the NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (P30 AR050950).

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the animal protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Abramowitch SD, Woo SL, Clineff TD, Debski RE. An evaluation of the quasi-linear viscoelastic properties of the healing medial collateral ligament in a goat model. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:329–335. doi: 10.1023/B:ABME.0000017539.85245.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansorge HL, Beredjiklian PK, Soslowsky LJ. CD44 deficiency improves healing tendon mechanics and increases matrix and cytokine expression in a mouse patellar tendon injury model. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1386–1391. doi: 10.1002/jor.20891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartolozzi A, Andreychik D, Ahmad S. Determinants of outcome in the treatment of rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994:90–97. [PubMed]

- 4.Bjorkenheim JM. Structure and function of the rabbit’s supraspinatus muscle after resection of its tendon. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60:461–463. doi: 10.3109/17453678909149320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorkenheim JM, Paavolainen P, Ahovuo J, Slatis P. Surgical repair of the rotator cuff and surrounding tissues. Factors influencing the results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:148–153. [PubMed]

- 6.Bokor DJ, Hawkins RJ, Huckell GH, Angelo RL, Schickendantz MS. Results of nonoperative management of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993:103–110. [PubMed]

- 7.Carpenter JE, Thomopoulos S, Flanagan CL, DeBano CM, Soslowsky LJ. Rotator cuff defect healing: a biomechanical and histologic analysis in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:599–605. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman SH, Fealy S, Ehteshami JR, MacGillivray JD, Altchek DW, Warren RF, Turner AS. Chronic rotator cuff injury and repair model in sheep. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2391–2402. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabis J, Kordek P, Bogucki A, Synder M, Kolczynska H. Function of the rabbit supraspinatus muscle after detachment of its tendon from the greater tubercle. Observations up to 6 months. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:570–574. doi: 10.3109/17453679808999257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favata M. Scarless healing in the fetus: Implications and strategies for postnatal tendon repair. 2006. Dissertations available from ProQuest. Paper AAI3246156. Available at: http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3246156.

- 11.Fukuda H, Hamada K, Yamanaka K. Pathology and pathogenesis of bursal-side rotator cuff tears viewed from en bloc histologic sections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990:75–80. [PubMed]

- 12.Gazielly DF, Gleyze P, Montagnon C. Functional and anatomical results after rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994:43–53. [PubMed]

- 13.Gerber C, Meyer DC, Schneeberger AG, Hoppeler H, Rechenberg B. Effect of tendon release and delayed repair on the structure of the muscles of the rotator cuff: an experimental study in sheep. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1973–1982. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B6.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gimbel JA, Kleunen JP, Mehta S, Perry SM, Williams GR, Soslowsky LJ. Supraspinatus tendon organizational and mechanical properties in a chronic rotator cuff tear animal model. J Biomech. 2004;37:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodmurphy CW, Osborn J, Akesson EJ, Johnson S, Stanescu V, Regan WD. An immunocytochemical analysis of torn rotator cuff tendon taken at the time of repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:368–374. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(03)00034-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo UG, Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Rabitti C, Morini S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Histopathology of the supraspinatus tendon in rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:533–538. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsen FA, III, Arntz CT. Rotator Cuff Tendon Failure. In: Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III, editors. The Shoulder. 1. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1990. pp. 647–677. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto F, Uhthoff HK, Trudel G, Loehr JF. Delayed tendon reattachment does not reverse atrophy and fat accumulation of the supraspinatus–an experimental study in rabbits. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:357–363. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews TJ, Hand GC, Rees JL, Athanasou NA, Carr AJ. Pathology of the torn rotator cuff tendon. Reduction in potential for repair as tear size increases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:489–495. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.16845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer DC, Jacob HA, Nyffeler RW, Gerber C. In vivo tendon force measurement of 2-week duration in sheep. J Biomech. 2004;37:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(03)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. After rotator cuff tears, the remaining (intact) tendons are mechanically altered. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. Alterations in function after rotator cuff tears in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubino LJ, Stills HF, Jr, Sprott DC, Crosby LA. Fatty infiltration of the torn rotator cuff worsens over time in a rabbit model. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safran O, Derwin KA, Powell K, Iannotti JP. Changes in rotator cuff muscle volume, fat content, and passive mechanics after chronic detachment in a canine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2662–2670. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, DeBano CM, Banerji I, Moalli MR. Development and use of an animal model for investigations on rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:383–392. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(96)80070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soslowsky LJ, Thomopoulos S, Tun S, Flanagan CL, Keefer CC, Mastaw J, Carpenter JE. Neer Award 1999. Overuse activity injures the supraspinatus tendon in an animal model: a histologic and biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:79–84. doi: 10.1016/S1058-2746(00)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomopoulos S, Soslowsky LJ, Flanagan CL, Tun S, Keefer CC, Mastaw J, Carpenter JE. The effect of fibrin clot on healing rat supraspinatus tendon defects. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:239–247. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.122228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto E, Hayashi K, Yamamoto N. Mechanical properties of collagen fascicles from the rabbit patellar tendon. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:124–131. doi: 10.1115/1.2798033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.