Abstract

Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) is promoted as a potential HIV prevention measure. We describe trends in uptake of VCT for HIV, and patterns of subsequent behaviour change associated with receiving VCT in a population-based open cohort in Manicaland, Zimbabwe. The relationship between receipt of VCT and subsequent reported behaviour was analysed using generalized linear models with random effects. At the third survey, 8.6% of participants (1,079/12,533), had previously received VCT. Women who received VCT, both those positive and negative, reduced their reported number of new partners. Among those testing positive, this risk reduction was enhanced with time since testing. Among men, no behavioural risk reduction associated with VCT was observed. Significant increases in consistent condom use, with regular or non-regular partners, following VCT, were not observed. This study suggests that, among women, particularly those who are infected, behavioural risk reduction does occur following VCT.

Keywords: HIV, Testing, Counselling, Sexual behaviour, Zimbabwe

Introduction

Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) is promoted as a primary prevention strategy to reduce the heterosexual transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Pre- and post-test counselling sessions are an opportunity to provide information on HIV, correct misconceptions, assist with risk assessment, provide emotional support, encourage disclosure of serostatus to partners, and discuss a risk reduction plan if necessary. To prevent new infections, VCT must motivate individuals to adopt safe sexual behaviour. Modelling studies have demonstrated the particular importance of sustained behaviour change and of reduced risk behaviour among those not infected in determining the population level impact of VCT, since these are the majority at risk [2].

Data from twelve African Demographic and Health Surveys conducted between 2003 and 2005, indicate that a median of only 12% of men and 10% of women had been tested for HIV and received their results [3]. However, provision of VCT in countries with generalized or high-burden epidemics has expanded dramatically in recent years, largely because of increased financial resources to provide treatment [3]. Recent guidance issued by WHO and UNAIDS recommends a routine (“opt-out”) approach to provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling [4]. In Botswana, the policy of routine HIV testing, implemented since 2004 [5], has led to rapid increases in testing uptake, with almost half of adults reporting having tested for HIV in a recent population based study [6].

Scale-up of testing services is closely linked to providing antiretroviral treatment [7]. However, for treatment programmes to be sustainable, reductions in incidence are required [8, 9]. Thus, preventing new infections through the provision of high quality counselling should be another, equally important, aim.

To date, there has been mixed evidence for the efficacy of VCT in promoting safer sexual behaviour in developed and developing countries [10, 11]. A multi-centre randomized controlled trial [12] and a number of observational studies in Africa have indicated moderate behavioural changes following VCT [12–21]. However, the greatest changes observed in these studies were among those testing positive and those in sero-discordant partnerships and little evidence exists for behavioural risk reduction among those found not to be infected [22, 23]. There is also concern as to whether the standard of VCT that can be administered in trials can realistically be provided and maintained routinely. Given the importance of longevity of behaviour change, and the lack of behavioural risk reduction among the majority of those testing (i.e. HIV negative individuals), the evidence for the effectiveness of VCT as a HIV prevention measure is relatively weak.

Longitudinal data on individuals receiving standard VCT, from the Manicaland cohort study, provides an opportunity to assess the association between receiving VCT and behaviour change, outside of an intervention trial of the efficacy of VCT. The aims of this study are to (1) describe the overall trends in uptake of VCT and (2) assess the patterns of behaviour change associated with receiving VCT, including whether they are sustained.

Methods

Participants

The Manicaland HIV/STD Prevention Project is a population-based open cohort study [24, 25]. Participants were recruited from four subsistence farming areas, two small towns, two roadside trading areas, and four forestry, coffee and tea estates in the Manicaland province of Eastern Zimbabwe. A preliminary household census was carried out at each site to identify individuals eligible for the study. The baseline survey was carried out in a phased manner from 1998 to 2000. Second (2001/2003) and third (2003/2005) rounds of the survey were conducted at each site, providing two rounds of follow-up for those retained from baseline and creating an open cohort with newly eligible individuals being recruited at each round. Initially, men aged 17–54 years and women aged 15–44 years were recruited with only one member of each marital union being selected at random to participate. In the third round, the entry criteria were extended to include all men and women aged between 15 and 54 years with both members of a marital union being eligible to participate. The household participation rates were 98, 94 and 96% in the first, second and third surveys, respectively. Individual participation rates were 79, 79 and 83% in the first, second and third surveys, respectively.

Dried blood spots were obtained for anonymous HIV serological testing. This testing was carried out using a highly sensitive and specific antibody dipstick assay [26].

Voluntary Counselling and Testing Services

Participants were offered free HIV counselling and testing at each survey. This service was available at a mobile clinic which was present within the study site at the time the survey was being conducted. Participants receiving VCT from the research programme did so after completing the survey questionnaire. During the baseline and second surveys, VCT clients were asked to return 2 weeks after testing, to receive their results and post-test counselling. At the third survey, rapid testing was introduced and clients received their results and post-test counselling on the same day of testing. Counselling was provided by trained male and female nurse counsellors. For those who participated in the third survey and had previously received VCT, the mean duration of pre- and post-test counselling was 37 and 21 minutes, respectively. Data regarding duration of counselling was not collected in the earlier surveys. VCT services provided by government and non-governmental organizations became increasingly available in the study areas over time.

Measures

Demographic and sexual behaviour data were collected at each survey. An informal confidential system of voting was used to collect behavioural data as a means of reducing social desirability bias [27]. Participants indicated their answer to each question on a colour coded voting strip, which they then placed in a locked “voting” box.

Behaviours which were analysed included the number of times the participant had visited a bar/beer hall in the previous month (which is known to be associated with risky sexual behaviour [28]), whether the participant had a sexual partner in the last month, the number of new partners in the last year, whether the participant had multiple concurrent partnerships (self-defined), and whether the participant reported consistent condom use (condoms used in all acts of intercourse over the most recent 2 weeks period) with regular (partnerships of greater than 1 year’s duration) and non-regular partners.

Data Analyses

All analyses considered the non-virgin population who had an unambiguous anonymous dipstick HIV test result. Participants who reported having been tested for HIV and having received their results were defined as having received VCT. Unfortunately, in the baseline survey, receipt of results was not established.

A binary indicator based on time since last test and collection of results was created which captured whether or not an individual had previous experience of VCT at each round. Reports given by respondents in the second survey were used to identify those who had received VCT previous to the second survey (i.e. at the first survey and between the first and second survey). Reports given by respondents in the third survey were used to identify those who had received VCT previous to the third survey (i.e. at the second survey and between the second and third survey).

Binary indicators were created for each of two time periods since receiving VCT (within the last 2 years and 2–3 years ago). These time-since-testing indicators were included in the models, to investigate how the effect of VCT changed with length of time since testing.

In analyzing the relationship between behaviour and VCT, we are interested in comparing behaviour before and after receiving VCT. Most reported behaviours refer to the month previous to the survey, so only those receiving VCT before that month are defined as having received VCT. However, number of new partners in the last year relates to a longer pre-survey period, so, for this variable only, those who tested over 12 months previously are defined as having received VCT.

Generalized linear models with random-effects [29] were fitted to investigate the reported behaviours in the study, including VCT as a variable in the model. Models adjusting for age (5 year categories), calendar year and marital status were fitted. Variables were dropped from the model one at a time if inclusion did not significantly improve the fit of the model (P < 0.05, likelihood ratio test).

In effect, these models allow us to explore behaviour change over time comparing those who received VCT to those who did not receive VCT, stratified by sex and HIV status. Repeated observations for individuals within the cohort mean that the data are not independent. This clustering of the data is incorporated explicitly in the model equations and the likelihood calculations using an individual-specific term (Gamma distributed for Poisson models, Gaussian distributed for Logistic models). Numeric outcomes were analysed using Poisson generalized linear models and binary outcomes were analysed using Logistic generalized linear models.

For those who tested, HIV status at the time of receiving VCT was used for stratification. In stratifying our analysis according to HIV status, we intended to examine whether those who received a positive test result changed their behaviour more than those with similar initial risks. However, we were also interested in changes in behaviour among those who received VCT and were negative at the time of testing. If we included those who seroconverted subsequent to VCT as positive in this analysis, we would bias our results for those testing negative to only those who remain negative. Therefore, those who seroconverted following VCT were considered as HIV negative in the analysis, as this was their status when they received VCT. Those who did not test and who seroconverted during follow-up were categorized as positive in the analysis. This assumption applied to 228 individuals (174 seroconversions among non-testers between baseline and the second survey and 52 between the second and third surveys). A sensitivity analysis showed that overall findings were unchanged when these individuals were assumed to be negative in the analysis.

Results

Survey Participation and Participant Characteristics

The open cohort consisted of 17,874 individuals; 7,559 men (42%) and 10,315 women (58%). The mean length of follow-up time was 4.2 years. At baseline, the median age among men was 29 years, compared to 30 years among women. HIV prevalence was 19.4, 17.9 and 16.5% among men aged 17–54 years in the first, second and third surveys, respectively, and 25.9%, 22.4 and 20.5% among women aged 15–44 years [30]. The socio-demographic characteristics of study participants included in this analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants at each survey

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3,787 (45.8) | 2,771 (42.3) | 4,711 (37.6) |

| Female | 4,486 (54.2) | 3,788 (57.7) | 7,822 (62.4) |

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 1,326 (16.0) | 764 (11.7) | 1,037 (8.3) |

| 20–29 | 3,363 (40.7) | 2,415 (36.8) | 4,808 (38.4) |

| 30–39 | 2,010 (24.3) | 1,647 (25.1) | 3,155 (25.2) |

| 40+ | 1,574 (19.0) | 1,733 (26.4) | 3,533 (28.2) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 2,321 (28.1) | 1,334 (20.3) | 1,833 (14.6) |

| Married | 4,715 (57.0) | 4,227 (64.5) | 8,465 (67.6) |

| Previously married | 1,237 (14.9) | 998 (15.2) | 2,235 (17.8) |

| Education | |||

| None | 306 (3.7) | 127 (1.9) | 9 (0.1) |

| Primary | 3,343 (40.4) | 2,582 (39.4) | 4,779 (38.1) |

| Secondary | 4,474 (54.1) | 3,672 (56.0) | 7,032 (56.1) |

| Higher | 150 (1.8) | 68 (1.0) | 208 (1.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 110 (1.7) | 505 (4.0) |

| Total | 8,273 | 6,559 | 12,533 |

Baseline behavioural data was compared for those who participated in all three surveys and those who were lost to follow-up due to migration, death, refusal or unavailability at the time of the follow-up visit. Those who were lost to follow-up were significantly more risky in terms of beer hall attendance, new partners in the last year, partners in the last month and number of current sexual relationships, without adjusting for age and sex (χ 2 test, P < 0.01 for all comparisons). These individuals also reported more consistent condom use (13% amongst those lost to follow-up vs. 7% amongst those not; χ 2 test statistic 24.5 (1 df), P < 0.01) with regular partners and (48% vs. 33%; χ 2 test statistic 8.1 (1 df), P < 0.01) with non-regular partners.

Overall, there have been declines in reported risk behaviours, among both men and women, during the study period. The mean levels of reported behaviour among men and women at the first survey and by testing status at the third survey are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean levels of reported behaviour at the first survey and by testing status at the third survey, among males and females in the open cohort

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 3 | Round 1 | Round 3 | |||

| Received VCT | Did not receive VCT | Received VCT | Did not receive VCT | |||

| Times visited bar or beer hall in the last month | 5.53 | 1.26 | 1.41 | 0.41 | 0.88 | 1.30 |

| Number of new sexual partners in past year | 1.10 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.31 |

| Number of sexual partners in past month | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| Number of current partners | 1.08 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| Consistent condom use in last 2 weeksa | ||||||

| With regular partner | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| With non-regular partner | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.34 |

aProportion reporting consistent condom use in last 2 weeks

Uptake of Testing and Counselling

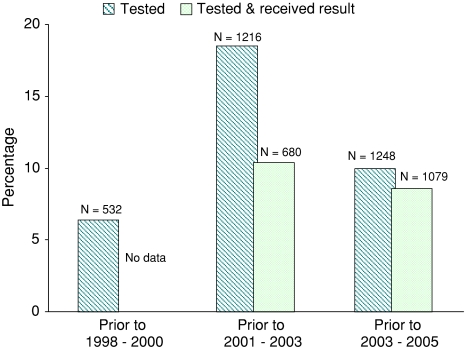

The reported uptake of testing, counselling and collection of results at each survey is shown in Fig. 1. In the second survey, 18% (1,216/6,559) of participants reported having had a previous HIV test. However, of these, only 56% (680/1,216) reported collecting their test results. In the third survey, 10% (1,248/12,533) of participants reported having tested. Of these, 86% (1,079/1,248) received their results. Overall, 8.6% (1,079/12,533) of participants in the third survey were defined as having previously received VCT. Individuals receiving VCT from the research programme at the third survey are not defined as having received VCT for analysis purposes, as they received VCT after completing the survey questionnaire.

Fig. 1.

Previous uptake of testing and results collection reported by individuals at each survey round (N = 17,874). In earlier study rounds (1998–2000 and 2001–2003) those who reported to have tested may include those who were tested for medical purposes but did not receive their results

VCT and Subsequent Sexual Behaviour

Against a background of considerable declines in risk behaviour, including reductions in casual sex, [25], no significant additional behavioural risk reduction associated with VCT was observed among either HIV positive or negative men (Table 3). Women who received VCT reduced their number of new sexual partners in the last year more than those who did not test (Table 3; Fig. 2). This was true regardless of HIV status, but greater additional reductions were observed among those receiving a positive test result. Women receiving a positive result also reduced their bar attendance in the last month more than those not testing. Men testing positive and women testing negative tended to report more visits to beer halls in the last month. Overall, levels of consistent condom use increased among men and women testing positive; however, these were not significant changes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sexual behaviour change following VCT, from generalized linear regression models predicting each behavioural outcome

| HIV positive | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |||||

| Exp(Coef.) | SE | 95% CI | Exp(Coef.) | SE | 95% CI | |

| Visited bar/beer hall in the last month | 1.26 | 0.09** | (1.10–1.44) | 0.38 | 0.16* | (0.17–0.85) |

| New sexual partner in past yeara | 0.75 | 0.16 | (0.50–1.12) | 0.38 | 0.13** | (0.20–0.73) |

| Sexual partner in past monthb | 1.19 | 0.33 | (0.69–2.05) | 0.92 | 0.19 | (0.61–1.37) |

| Multiple concurrent partnersb | 0.72 | 0.32 | (0.31–1.70) | 0.46 | 0.58 | (0.04–5.35) |

| Consistent condom use in last 2 weeks | ||||||

| With regular partnersb | 1.65 | 0.74 | (0.68–3.98) | 1.89 | 0.76 | (0.86–4.16) |

| With non-regular partnersb | 0.65 | 0.55 | (0.12–3.45) | 2.07 | 2.69 | (0.16–26.42) |

| HIV negative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |||||

| Exp(Coef.) | SE | 95% CI | Exp(Coef.) | SE | 95% CI | |

| Visited bar/beer hall in the last month | 1.02 | 0.04 | (0.94–1.11) | 1.66 | 0.39* | (1.05–2.64) |

| New sexual partner in past yeara | 0.87 | 0.08 | (0.72–1.04) | 0.69 | 0.12* | (0.48–0.97) |

| Sexual partner in past monthb | 0.89 | 0.12 | (0.68–1.17) | 0.91 | 0.10 | (0.73–1.12) |

| Multiple concurrent partnersb | 1.11 | 0.25 | (0.71–1.73) | 0.98 | 0.66 | (0.23–4.26) |

| Consistent condom use in last 2 weeks | ||||||

| With regular partnersb | 0.96 | 0.38 | (0.45–2.08) | 1.39 | 0.38 | (0.81–2.39) |

| With non-regular partnersb | 1.08 | 0.41 | (0.51–2.28) | 0.01 | 0.02 | (0.00–2.80) |

Exponentiated coefficients describe the change in the outcome variable associated with receiving VCT, stratified by sex and HIV status

Results are adjusted for age, calendar year and marital status, see “Methods” for details

Exp(Coef.): Exponentiated coefficient. A value of 1 indicates no change

SE: Standard error

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

aThose who had tested within the year before the survey were categorized as not tested when defining the indicator for having received VCT

bModelled as a binary variable

Fig. 2.

Relative change in the number of new partners in the last year, following VCT. The results in the above figure are based on comparing those who received VCT to those who did not receive VCT. Thus, this figure illustrates the additional reduction in mean number of new partners in the last year associated with receiving VCT. The 0% indicates no change. Results are adjusted for age (5 year categories), calendar year and marital status. The relative change is calculated as: Exp(Coef.) − 1

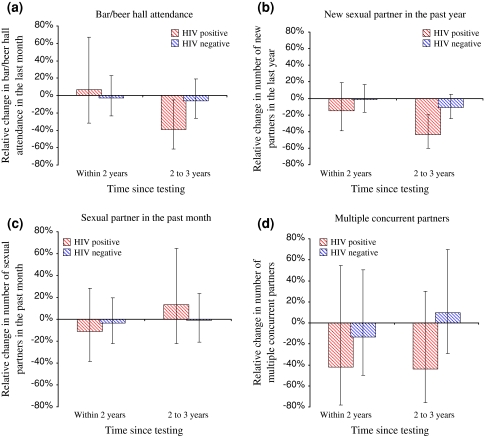

The effect of VCT in reducing risk behaviour increased with greater time (2–3 years) since testing among those testing positive, with respect to new sexual partners in the last year and bar attendance (Fig. 3). No significant trends were observed in the effect of VCT over time with respect to sexual partners in the past month. Reduced levels of concurrency, among those testing positive, were maintained for 2–3 years following testing.

Fig. 3.

The effect of VCT on behaviour in relation to time since testing. The results are based on comparing those who received VCT to those who did not receive VCT. Thus, these figures illustrate the additional change in behaviour associated with receiving VCT. Results are adjusted for age (5 years categories) and sex. a Bar/beer hall attendance. b New sexual partner in the past year. c Sexual partner in the past month. d Multiple concurrent partners

Discussion

As a scale-up in provision of VCT services and access to treatment in sub-Saharan Africa is underway, it is important to monitor the uptake of VCT and its impact on sexual behaviour. In this rural Zimbabwean population, the uptake of VCT services is increasing gradually, but remains low compared with some other countries with generalized HIV epidemics [3]. Promisingly, we found that women receiving VCT reduce the number of sexual partnerships they form. Although the changes were greatest for those testing positive, substantial reductions were also seen for those receiving negative test results. Similar patterns of change were observed for men, but the differences were smaller and not statistically significant. These gender differentials in the effectiveness of VCT for promoting safer sexual behaviour suggest that women may be more receptive to risk reduction counselling than men, in this setting. These risk reductions observed following VCT are particularly encouraging because they are not based on results from a trial of VCT, where services may be implemented more assiduously than they can be done when scaled-up.

Reductions in risk appear to be maintained or even enhanced, only for those testing positive, perhaps due to deteriorating health. However, inconsistencies in reporting of time since receiving VCT suggest recall bias may have affected these results. An informal confidential voting method was used to minimise social desirability bias in reported sexual behaviour following receipt of risk reduction counselling. Furthermore, the counselling provided by the study was intended to be supportive and not didactic. Also, there was no evidence for increases in consistent condom use. The finding that those lost to follow-up tended, in some respects, to be of a higher risk profile than those followed-up over the study period may mean that we underestimated the potential effect of VCT, since high risk individuals have the greatest potential for substantial reductions in risk.

These results confirm previous findings in this population, which used two rounds of data and different statistical methods, where greater reductions in risk behaviours were seen among individuals testing positive—but not among individuals testing negative—than in the general population [19]. However, importantly, concerns over increased risk behaviour among individuals testing negative, were not confirmed in the current study. The differences in findings may reflect changes occurring over time in the context, nature (including quality), profile of testers, and effect of VCT, as well as the differences in the statistical methods used. Unlike in the earlier analysis, account was taken here of the magnitude of change in particular behavioural variables. Furthermore, the current analysis is stratified by HIV infection status, whereas the earlier report was based on separate comparisons between positive and negative individuals who took up VCT and all individuals (i.e. positive and negative individuals combined) who had not received VCT.

Overall, evaluating the evidence for the impact of VCT on sexual behaviour is difficult because studies are diverse with respect to design, outcome measures, statistical analyses and comparison groups, participant characteristics and service provision. Our finding that VCT is more effective for risk reduction among those testing positive is consistent with findings from a multicenter randomized controlled trial [12]. However, this study reports reductions in formation of new partnerships, whereas the outcome of interest in the randomized controlled trial was unprotected intercourse. Nonetheless, our findings are generally consistent with the conclusions of two previous meta-analyses [10, 11]. Our findings are in contrast to those of Matovu et al. [23], who report no difference in number of sexual partners among acceptors and non-acceptors of VCT, and no significant change in risk during follow-up among those who accepted or refused VCT, in Rakai, Uganda. However, almost half of participants (50.9% of VCT acceptors and 41.2% of non-acceptors) had previously received home-based VCT from the Rakai program. Thus, it may not be surprising that no behavioural differences were observed.

In Zimbabwe, there have been widespread reductions in risk behaviour over the study period [25]. We observed declines in risk behaviour among individuals who did not test, as well as among those who tested. However, these behavioural trends have been accounted for in these analyses, in order to distinguish behavioural changes associated with receiving VCT from background reductions in risk. It is encouraging that VCT can be effective in reducing risk behaviour in such a context but it is not known whether the level of uptake of VCT or the more extensive reductions in risk behaviour seen amongst individuals who took up VCT would have been the same in the absence of this underlying pattern of behaviour change. Previous studies of VCT services in Zimbabwe have achieved higher levels of uptake than was observed in the current study in contexts such as antenatal clinics [31], workplace VCT programmes [32], and mobile same day testing [33]. The profile of testers and the effect of VCT are likely to differ according to the method of VCT provided and the specific context in which it is offered, so it is uncertain to what extent our results can be generalized beyond the particular study setting [34–36]. Furthermore, the current study was undertaken in the pre-ART era. The expansion of VCT services, provision of treatment, and the switch to provider-initiated VCT will likely have important implications for the demand for VCT and its effect on sexual behaviour. Lack of treatment has almost certainly been a barrier to uptake of VCT in this population, as the majority (83%) of participants at the third survey reported that they would test if cheap treatment was available.

Our data do not capture short-lived changes in behaviours measured over the short-term, such as consistent condom use and concurrency. Thus, if an individual reduced their risk immediately after VCT, but this risk reduction was not maintained until the subsequent study survey, this change would not be identified. Mathematical modelling studies of the population-level impact of VCT have found that a critical determinant of the preventive benefits of VCT is the duration of changes in behaviour [2]. If high risk sexual behaviour is reduced following VCT, but these reductions are not maintained, the epidemiological impact of the intervention will be greatly reduced. Furthermore, slight changes in behaviour among negative individuals can result in substantial impact at the population level as the majority of the population will be uninfected.

VCT arguably represents the best opportunity for encouraging sexual behaviour change, which is essential if the transmission of HIV is to be abated and the provision of treatment is to be sustainable. Provision and uptake of testing is increasing as efforts to find infected individuals to start therapy intensify. But, for VCT to be a successful prevention intervention, it must lead to sustained risk reduction among both infected and uninfected individuals. Thus, the importance of adopting and maintaining reductions in risk behaviour must be emphasized through high-quality counselling.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Chisvo, E. Dauka, M. Kakowa, J. Magwere, P.R. Mason, M. Mlilo, C. Mundandi, P. Mushati, J. Mutsvangwa, Z. Mupambireyi, M. Wambe and C. Zvidzai for assistance with data collection and laboratory diagnostics, and the people of Manicaland for their participation in the research. We thank K. Marsh for helpful comments and discussion. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust; and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.De Cock KM, Marum E, Mbori-Ngacha D. A serostatus-based approach to HIV/AIDS prevention and care in Africa. Lancet. 2003;362(9398):1847–1849. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallett TB, Dube S, Cremin I, Lopman B, Mahomva A, Ncube G, et al. The role of testing and counselling for HIV prevention and care in the era of scaling-up antiretroviral therapy. Epidemics. 2009 (In press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF. Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Progress Report; April 2007.

- 4.UNAIDS, WHO. Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities; May 2007.

- 5.Steen TW, Seipone K, Gomez Fde L, Anderson MG, Kejelepula M, Keapoletswe K, et al. Two and a half years of routine HIV testing in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(4):484–488. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318030ffa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiser SD, Heisler M, Leiter K, Korte FP, Tlou S, Demonner S, et al. Routine HIV testing in Botswana: a population-based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallett TB, Gregson S, Dube S, Garnett GP. The impact of monitoring HIV patients prior to treatment in resource-poor settings: insights from mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2008;5(3):e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stover J, Bertozzi S, Gutierrez JP, Walker N, Stanecki KA, Greener R, et al. The global impact of scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention programs in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2006;311(5766):1474–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1121176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salomon JA, Hogan DR, Stover J, Stanecki KA, Walker N, Ghys PD, et al. Integrating HIV prevention and treatment: from slogans to impact. PLoS Med. 2005;2(1):e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denison JA, O’Reilly KR, Schmid GP, Kennedy CE, Sweat MD. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Voluntary HIV-1 Counselling and Testing Efficacy Study Group Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9224):103–112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamenga M, Ryder RW, Jingu M, Mbuyi N, Mbu L, Behets F, et al. Evidence of marked sexual behavior change associated with low HIV-1 seroconversion in 149 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: experience at an HIV counselling center in Zaire. AIDS. 1991;5(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson DJ, Rakwar JP, Richardson BA, Mandaliya K, Chohan BH, Bwayo JJ, et al. Decreased incidence of sexually transmitted diseases among trucking company workers in Kenya: results of a behavioural risk-reduction programme. AIDS. 1997;11(7):903–909. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth DL, Stewart KE, Clay OJ, van Der Straten A, Karita E, Allen S. Sexual practices of HIV discordant and concordant couples in Rwanda: effects of a testing and counselling programme for men. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(3):181–188. doi: 10.1258/0956462011916992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, Zulu I, Trask S, Fideli U, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiktor SZ, Abouya L, Angoran H, McFarland J, Sassan-Morokro M, Tossou O, et al. Effect of an HIV counseling and testing program on AIDS-related knowledge and practices in tuberculosis clinics in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(4):445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mola OD, Mercer MA, Asghar RJ, Gimbel-Sherr KH, Gimbel-Sherr S, Micek MA, et al. Condom use after voluntary counselling and testing in central Mozambique. Tropical Med Int Health. 2006;11(2):176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherr L, Lopman B, Kakowa M, Dube S, Chawira G, Nyamukapa C, et al. Voluntary counselling and testing: uptake, impact on sexual behaviour, and HIV incidence in a rural Zimbabwean cohort. AIDS. 2007;21(7):851–860. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32805e8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arthur G, Nduba V, Forsythe S, Mutemi R, Odhiambo J, Gilks C. Behaviour change in clients of health centre-based voluntary HIV counselling and testing services in Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(7):541–546. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen S, Tice J, Van de Perre P, Serufilira A, Hudes E, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. Effect of serotesting with counselling on condom use and seroconversion among HIV discordant couples in Africa. BMJ. 1992;304(6842):1605–1609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6842.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matambo R, Dauya E, Mutswanga J, Makanza E, Chandiwana S, Mason PR, et al. Voluntary counseling and testing by nurse counselors: what is the role of routine repeated testing after a negative result? Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(4):569–571. doi: 10.1086/499954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matovu JK, Gray RH, Makumbi F, Wawer MJ, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, et al. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing acceptance, sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2005;19(5):503–511. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162339.43310.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Mason PR, Zhuwau T, Carael M, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1896–1903. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett TB, Lewis JJ, Mason PR, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311(5761):664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray CS, Mason PR, Smith H, Rogers L, Tobaiwa O, Katzenstein DA. An evaluation of dipstick-dot immunoassay in the detection of antibodies to HIV-1 and 2 in Zimbabwe. Tropical Med Int Health. 1997;2(1):83–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregson S, Mushati P, White PJ, Mlilo M, Mundandi C, Nyamukapa C. Informal confidential voting interview methods and temporal changes in reported sexual risk behaviour for HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(Suppl 2):ii36–ii42. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis JJ, Garnett GP, Mhlanga S, Nyamukapa CA, Donnelly CA, Gregson S. Beer halls as a focus for HIV prevention activities in rural Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Diseases. 2005;32(6):364–369. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154506.84492.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. London: Chapman and Hall; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregson S, Nyamukapa C, Lopman B, Mushati P, Garnett GP, Chandiwana SK, et al. Critique of early models of the demographic impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa based on contemporary empirical data from Zimbabwe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(37):14586–14591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611540104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shetty AK, Mhazo M, Moyo S, von Lieven A, Mateta P, Katzenstein DA, et al. The feasibility of voluntary counselling and HIV testing for pregnant women using community volunteers in Zimbabwe. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(11):755–759. doi: 10.1258/095646205774763090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corbett EL, Dauya E, Matambo R, Cheung YB, Makamure B, Bassett MT, et al. Uptake of workplace HIV counselling and testing: a cluster-randomised trial in Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morin SF, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Charlebois ED, Routh J, Fritz K, Lane T, et al. Removing barriers to knowing HIV status: same-day mobile HIV testing in Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(2):218–224. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000179455.01068.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glick P. Scaling up HIV voluntary counseling and testing in Africa: what can evaluation studies tell us about potential prevention impacts? Eval Rev. 2005;29(4):331–357. doi: 10.1177/0193841X05276437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hallett TB, White PJ, Garnett GP. Appropriate evaluation of HIV prevention interventions: from experiment to full-scale implementation. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(Suppl 1):i55–i60. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alary M, Lowndes CM, Boily MC. Community randomized trials for HIV prevention: the past, a lesson for the future? AIDS. 2003;17(18):2661–2663. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200312050-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]