Abstract

Proteins with high-sequence identity but very different folds present a special challenge to sequence-based protein structure prediction methods. In particular, a 56-residue three-helical bundle protein (GA95) and an α/β-fold protein (GB95), which share 95% sequence identity, were targets in the CASP-8 structure prediction contest. With only 12 out of 300 submitted server-CASP8 models for GA95 exhibiting the correct fold, this protein proved particularly challenging despite its small size. Here, we demonstrate that the information contained in NMR chemical shifts can readily be exploited by the CS-Rosetta structure prediction program and yields adequate convergence, even when input chemical shifts are limited to just amide 1HN and 15N or 1HN and 1Hα values.

Keywords: NMR, chemical shift, structure prediction, CS-Rosetta

Introduction

It is well known that protein families whose members share the same tertiary fold frequently have similar amino acid sequences. This correlation underlies many of the computational structure prediction approaches and makes it possible to build good quality structural models for all members in a family even when the structure of only a single member has been determined experimentally. It also provides the rationale for structural genomics, which aims to determine experimentally the high-resolution structure for at least one protein in each family and build structures for the remainder using computational methods.1 Current structure prediction methods can be separated into two classes: (1) comparative homology modeling or threading, which rely on detectable similarity between the modeled sequence and at least one protein of known structure2,3 and (2) de novo methods, which use the amino acid sequence to predict secondary structure and compatible low energy folds.4–8

Despite the requirement for comparative modeling to know the structure of at least one family member, it has proven to be a popular method, which reliably can predict the 3D structure of a protein, often at an accuracy comparable to low resolution experimentally determined structures.9

Nevertheless, different folds for proteins with high-sequence identity (>30%) also have been identified in recent years, and such cases may provide insight into the evolution of the wide array of protein folds found in nature.10 In an effort to enhance our understanding of this evolution of protein folds and fold switching, multiple pairs of proteins with sequence identities of up to 95% but distinctly different folds have been designed and studied experimentally by NMR spectroscopy.11–13 As expected, comparative modeling approaches have difficulties in selecting the correct template from the known three-dimensional structures when their sequences but not their structures converge, making it challenging to build the correct tertiary structure by this approach. For example, extensively mutated versions of the albumin-binding domain (GA) and IgG-binding domain (GB) of protein G, GA95 and GB95, were included in the CASP8 structure prediction contest and, importantly, the coordinates for GA88 and GB88 had not yet been released before the closing deadline for this contest. CASP8, therefore, provides an excellent opportunity to evaluate how challenging structure prediction of GA95 and GB95 is, despite the small size of these proteins. The vast majority of about 300 server-generated CASP8 entries submitted for each of the two proteins, using about 65 different servers, was based on comparative homology modeling (GA95: http://predictioncenter.org/casp8/results.cgi?view=tables&target=T0498-D1&model; GB95: http://predictioncenter.org/casp8/results.cgi?view=tables&target=T0499-D1&model). Whereas entries submitted for GB95 included a large percentage (89%, 266 out of 299) that showed the correct fold, only 12 out of 300 entries for GA95 exhibited the three-helical bundle topology observed experimentally, whereas the majority predicted it to have the mixed α/β fold of GB95. In passing, we note that human refinement and inspection of the predicted models sometimes can impact the outcome. For GA95 and GB95, out of the additional 218 and 220 such generated models 3.7% (eight in total, of which four from the Baker laboratory) and 86.4% (190) predicted the correct fold, respectively.

It has long been known that NMR chemical shifts contain important structural information for proteins. These chemical shifts, which generally are obtained at the early stage of any NMR protein structure study, can guide de novo protein structure prediction methods,14 as recently demonstrated for more than two dozen proteins with sizes of up to 130 amino acids and a variety of different folds.15–18 Notably, the chemical-shift Rosetta structure prediction method (CS-Rosetta) has also been tested in a blind manner for proteins whose experimental structure was not yet available at the time the structures were generated.17 In this work, we demonstrate that CS-Rosetta is able to unambiguously generate high quality structures with correct but distinct folds for a set of proteins with sequence identities of up to 95%. We demonstrate that even a small subset of the potentially available NMR chemical shifts already suffices to guide Rosetta to the correct fold.

Results and Discussion

Sequence convergence while retaining distinct folds

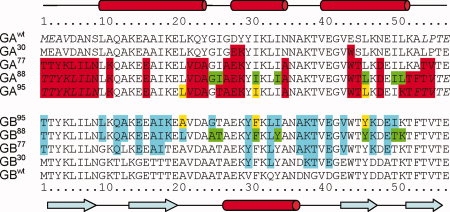

Starting from a pair of 56-residue wild-type proteins, the human serum albumin (HSA)- and IgG-binding domains of streptococcal protein G, GA (referred to as GAwt),19 and GB1 (GBwt),20 previously four pairs of mutated proteins were designed with pairwise sequence identities of 30% (referred to as GA30 and GB30), 77% (GA77, GB77), 88% (GA88, GB88), and 95% (GA95, GB95).11,12 These mutations and the aligned sequences are summarized in Figure 1. To reach the final, 95% identical sequences while retaining the initial starting folds, a total of 26 mutations were made in wild-type GA, resulting in GA95 (with sequence identity of 54% relative to GAwt, Table S1), and 20 substitutions in wild-type GB1 resulted in GB95 (64% identical to GBwt). The four structures for protein pairs GA88/GB88 and GA95/GB95 were solved experimentally by NMR and confirm that the GA/GB groups of proteins retain the same (3α)/(4β + α) folds as their wild-type templates GAwt/GBwt.12,13

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences of GAwt, GBwt, and their variants. The secondary structure of GAwt and GBwt, as identified by DSSP21 for GA88 (PDB entry 2JWS) and GB88 (2JWU), is indicated at the top and bottom of the figure, respectively. Residues that exhibit high-local disorder in the experimental NMR structures (>0.5 Å backbone atom rmsd for the tripeptides centered at this residue) are italicized. Residues that are changed from their wild-type sequences are highlighted in red and cyan for the variants of GAwt and GBwt, respectively. The unique amino acids in the variant pairs of GA95 and GB95, GA88 and GB88 are highlighted in yellow and green, respectively.

Structures obtained by standard Rosetta

Before discussing the results of CS-Rosetta, we first briefly evaluate the performance of standard Rosetta for the case where mutations make the GAwt and GBwt increasingly similar in sequence.

For any short stretch (originally of three- or nine-residue length, but flexible in newer versions of the program) in a given query protein, Rosetta first selects a large collection (ca. 200) of short fragments from its structural database that are most consistent with the local amino acid sequence and the secondary structure profile predicted for the query protein. Assuming that the native state of a protein is at the global free energy minimum, Rosetta uses a Monte Carlo search procedure to pick fragments from its collection to generate compact folds which are subsequently refined to optimize empirical hydrogen bonding terms, packing of hydrophobic sidechains, and a number of other terms to reach an empirical energy as low as possible. By default, three separate programs, Psipred,22 SAM-T99,23 and JUFO,24 are used by standard Rosetta to predict secondary structure (Supporting Information Fig. S1), which guides the standard Rosetta fragment selection process.

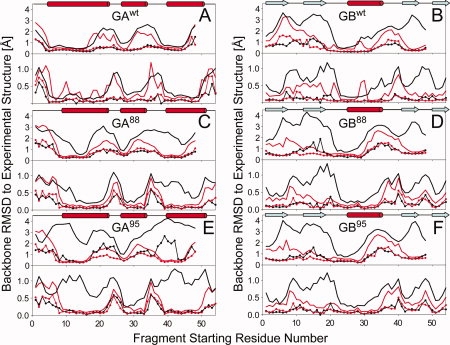

For the wild type GA and GB sequences, secondary structure prediction by all three programs is remarkably accurate, and even when a modest number of mutations are present (GA30 and GB,30 Supporting Information Table S1), predictions remain quite good (Supporting Information Fig. S1). However, when additional mutations are introduced (Fig. 1), the secondary structure predicted for both GA77 and GA88 by the three separate programs no longer shows consensus and also includes erroneous β-strand components. For variants GB77 and GB88, some lengthening of the α-helix in the N-terminal direction and a concomitant shortening of its preceding β-strand is predicted (Supporting Information Fig. S1). As a result, the Rosetta-selected fragments for these mutants exhibit considerably lower average accuracy (Fig. 2; Supporting Information Fig. S2). On the other hand, the “best” Rosetta-selected fragment remains close to that of the actual wild-type structure [Fig. 2(C–F)], even though the fraction of fragments with the correct backbone geometry becomes low. Because of the low likelihood that such a correct fragment is sampled during the Monte Carlo model building procedure, reaching the lowest energy correct fold becomes an inefficient process, and far fewer models converge to the correct fold [Supporting Information Fig. S3(E,G)]. Nevertheless, for variants GA77 and GA88, the lowest energy Rosetta models exhibit the correct fold and fall within ∼2 to 4 Å coordinate rmsd relative to the backbone atoms of the experimental structures [Table I; Supporting Information Fig. S3(E,G)].

Figure 2.

Quality of Rosetta/CS-Rosetta fragments used as input for deriving GA and GB models, shown as plots of the lowest (lines with dots) and average (bold lines) backbone coordinate rmsd's (N, Cα, and C′) between any given segment in the experimental structure and 200 nine-residue (upper panel)/three-residue (lower panel) fragments, as a function of starting position of the query segment. Results from the standard Rosetta fragment selection method are plotted in black, whereas those selected using the standard MFR method with chemical shifts are displayed in red. (A) GAwt; (B) GBwt; (C) GA88; (D) GB88; (E) GA95; and (F) GB95. Note that for nine-residue fragments, the last residue starting number in the 56-residue protein is 48, whereas for three-residue fragments, the last starting position is 54.

Table I.

Statistics of Predicted Structures for GAwt, GBwt, and Variants GA88/95 and GB88/95

| Rosetta |

CS-Rosettaa |

CS-Rosetta (δ1H only)b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSDbbc | RMSDalld | RMSDbbc | RMSDalld | RMSDbbc | RMSDalld | |

| GAwt | 1.74 | 2.36 | 1.54 | 2.20 | 1.37 | 2.14 |

| GBwt | 0.55 | 1.32 | 0.47e | 1.31 | 1.00 | 1.55 |

| GA88 | 2.36 | 3.26 | 1.62 | 2.54 | 1.81 | 2.66 |

| GB88 | 4.32 | 5.02 | 1.13e | 2.05 | 1.41 | 2.40 |

| GA95 | 8.68 | 9.67 | 1.76 | 2.83 | 2.01 | 3.10 |

| GB95 | 2.44 | 3.68 | 1.45e | 2.32 | 1.50 | 2.44 |

CS-Rosetta results with chemical shifts for backbone and 13Cβ atoms.

CS-Rosetta results with only 1HN and 1Hα chemical shifts.

rmsd (Cα, C′, and N) in units of Angstrom of the lowest-energy model to the experimental NMR structure (PDB entries 2fs1, 1pga, 2jws, 2jwu, 2kdl, and 2kdm for GAwt, GBwt, GA88, GB88, GA95, and GB95, respectively). Disordered residues 1 to 8 and 54 to 56, as identified in GA88 (PDB entry 2jws), are excluded from all GA rmsd calculations.

rmsd (all non-H atoms) of the lowest-energy model to the experimental structure.

Backbone rmsd for CS-Rosetta structures of GBwt, GB88, and GB95 relative to the wild-type X-ray structure (PDB entry 1PGA) equal 0.47, 1.07, and 0.90 Å, respectively.

The low-energy Rosetta models for variants GB77 and GB88 all exhibit GB-like 4β + α folds, but interestingly the lowest energy GB77 Rosetta models show β-strand pairing that differs from the experimental GBwt/GB88 structures [Supporting Information Fig. S3(F)]. The lowest energy Rosetta models of GB88 show the correct β-strand pairing pattern, but deviate by about 4–5 Å from the backbone coordinates of the experimental GB88 structure [Supporting Information Fig. S3(H)].

For GA77/GA88, only SAM-T99 correctly predicts the secondary structure. Nevertheless, Rosetta remains capable of generating approximately correct folds owing to its Monte Carlo selection of “working fragments” from its initial library of fragments. When SAM-T99 secondary structure prediction results were excluded for generating this Rosetta fragment library, no GA77/GA88 models with <4 Å backbone rmsd from the experimental structure were obtained (data not shown).

For GA95, which differs from GA88 by just two additional mutations at residues 25 and 50 (Fig. 1), the output of all three programs switched to that of the GB-like 4β + α secondary structure (Supporting Information Fig. S1) and Rosetta-generated models converge to the typical GB-like 4β + α fold instead of the experimentally observed GA-like 3α fold [Table I; Fig. 2(E); Supporting Information Fig. S3(I)]. For GB95, Rosetta remains effective at generating full-atom models with the correct 4β + α fold and reasonable coordinate accuracy [Table I; Supporting Information Fig. S3(J)].

Structure generation from chemical shifts using CS-Rosetta

The recently described chemical-shift-based Rosetta (CS-Rosetta) procedure17,25 generates protein structures in much the same way as standard Rosetta but uses the MFR program26 to select its fragments on the basis of chemical shifts observed in the protein of unknown structure. After Rosetta generation of low-energy protein models, based on these starting fragments, agreement between chemical shifts predicted for each of these Rosetta models by the program SPARTA27 and experimental values is used to add a pseudoenergy term to the standard Rosetta energy, which is then used for selecting viable models.

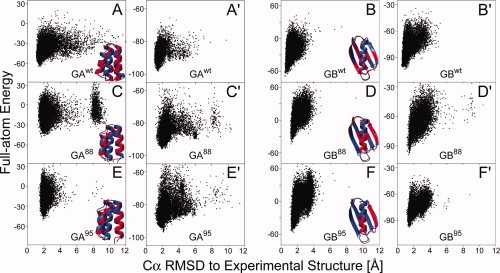

Comparison of the quality of the fragments selected by CS-Rosetta to those of standard Rosetta shows that for GAwt addition of chemical shift information only results in marginally closer matches between the coordinates of the selected fragments and the corresponding segments in the experimental GAwt structure [Fig. 2(A)]. On the other hand, for GBwt [Fig. 2(B)], the fragments selected by CS-Rosetta on average match much closer to the experimental structure, in particular for strands β2 and β4. Consequently, convergence of low energy GBwt structures is much higher for CS-Rosetta than for standard Rosetta, even though in the end both methods yield good accuracy for the lowest energy models [Fig. 3(B); Supporting Information Fig. S3(B)].

Figure 3.

CS-Rosetta structure generation for proteins GAwt, GBwt and variants GA88/95 and GB88/95. (A–F) Plot of Rosetta all-atom energy, rescored by using the input chemical shifts, versus Cα rmsd relative to the experimental structure, for all CS-Rosetta models of proteins GAwt (A), GBwt (B), GA88 (C), GB88 (D), GA95 (E), and GB95 (F). Following the protocol of Shen et al.,17 for all models the residues identified as disordered based on their RCI-derived order parameter (e.g., 1–8 and 52–56 in GA88) are excluded from the calculation of the Cα rmsd and from the Rosetta energy during model selection. Backbone ribbon representation of the lowest-energy CS-Rosetta structure (red) superimposed on the experimental structure (blue) of proteins is shown at the lower right corner of each panel. (A′–F′) Analogous plots of Rosetta all-atom energy, rescored by using the input chemical shifts (δ1Hα and δ1HN only), for the CS-Rosetta models obtained when using only 1H chemical shifts.

For both GA88 and GB88, fragments selected by standard Rosetta greatly decrease in accuracy compared with the wild type proteins, whereas CS-Rosetta fragment quality remains comparable to that obtained for the wild type proteins [Fig. 2(C,D)]. Consequently, CS-Rosetta closely reproduces the experimental structures [Fig. 3(C,D); Table I]. Similarly, for GA95 and GB95, the fragments selected by MFR remain of high quality [Fig. 2(E,F)], ensuring success of the subsequent Rosetta assembly and refinement process [Fig. 3(E,F)].

The backbone atomic coordinates of the lowest energy CS-Rosetta models of GAwt, GA88, and GA95 are within 1.5, 1.6, and 1.8 Å from their respective experimental structures (Table I); the lowest energy CS-Rosetta models of GBwt, GB88, and GB95 fall even closer to their experimental structures (Table I). Remarkably, the backbone coordinates of the CS-Rosetta structures for GBwt, GB88, and GB95 are slightly more similar to one another, and to the experimental X-ray structure of GBwt, than to the corresponding experimental NMR structures (Table I).

Performance of CS-Rosetta with limited chemical shifts

The earlier evaluation of CS-Rosetta used a very extensive set of NMR chemical shifts, including those of 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′,15N, 1HN, and 1Hα. The close correlation between secondary structure or backbone torsion angles and 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts is well established28–30 and dominates selection of accurate fragments by the MFR program, where amino acid sequence and therefore mutations of the GA and GB proteins have only a minor impact. On the other hand, the structure of small proteins such as GA and GB can be and has been determined by standard 1H-only NMR methods.31,32 The correlation between secondary structure and 1HN and 1Hα chemical shifts is considerably less pronounced than for 13Cα and 13Cβ, and indeed the quality of MFR-selected fragments for GA95 and GB95 when using only these shifts is considerably lower (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Despite this decrease in fragment accuracy, Rosetta is able to generate good converged models for both GA95 and GB95 [Fig. 3(E′,F′); Table I]. Similarly, correct lowest energy models are generated when using only the 1HN and15N chemical shift data as input for the MFR program [Supporting Information Fig. S4(E,F)]. However, 1HN chemical shifts alone are insufficient and their use does not yield converged structures for either GA95 or GB95 (data not shown).

Materials and Methods

Rosetta structure prediction from amino acid sequence

Standard Rosetta predictions33 were performed for wild-type proteins GAwt and GBwt and all their variants. Two hundred fragments were selected from the Rosetta structural database for each overlapped nine-residue and three-residue segment in the query protein. Selection was based on a combined score from (1) a sequence profile–profile similarity score, obtained from comparing the PSI-BLAST sequence profiles for the query sequence and each sequence in the Rosetta database, and (2) a secondary structure similarity score, calculated by comparing the (combined) predicted secondary structure (by the programs Psipred, SAM-T99, and JUFO; Supporting Information Fig. S1) of the query protein with the DSSP-assigned secondary structure21 of each protein in the database. A standard Rosetta Monte Carlo fragment assembly and relaxation procedure33 was then applied to generate 10,000 full-atom models.

CS-Rosetta structure generation from chemical shifts

Nearly complete backbone chemical shift assignments (δ15N, δ13C′, δ13Cα, δ13Cβ, δ1Hα, and δ1HN) were available for GAwt (with BMRB accession code 6945 and a reference structure from PDB entry 2FS1), GBwt (7280 and 1PGA), GA88 (15535 and 2JWS), GB88 (15537 and 2JWU), GA95 (16116 and 2KDL), and GB95 (16117 and 2KDM). Adjustment of the 1H chemical shifts by addition of 0.2 ppm to all values was needed when using 1H chemical shifts only. The need for such a reference adjustment was indicated by the chemical shift checking module of the CS-Rosetta package, and also by the −0.18 ± 0.10 ppm systematic differences between the 1Hα shifts of the unstructured N-terminal residues (2–8) of GA88 and GA95 and random coil values.34 These entries were subsequently updated in the BMRB.

The standard CS-Rosetta protocol17 was used to generate structures for GAwt, GBwt, and its mutants. To ensure that the evaluation was not facilitated by the fact that the structural database contains two GA and GB family members in the Rosetta protein structural database, proteins with significant sequence homology (PSI-BLAST e-score < 0.05, Table S3) were excluded before the fragment search procedure. Note, however, that not excluding these proteins slightly improves the quality of the MFR-selected fragments, for both the wild-type proteins and all of its mutants, including GA95.

All Rosetta/CS-Rosetta structure generations were performed using the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the NIH (http://biowulf.nih.gov) and Rosetta@Home supported by the BOINC project.

Comparative structure prediction with CS23D

The CS23D structure predictions for protein pair GAwt, GBwt and variant pairs GA88/GB88 and GA95/GB95 were performed using the CS23D web server,18 using all available15N, 13C′, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 1Hα, and 1HN chemical shift assignments and with the option “Ignore exact Matching Structures in Calculation.” The 10 lowest energy models returned for each protein by the server were evaluated in our study.

Concluding Remarks

Recently, a hybrid intermediate between standard and CS-Rosetta was introduced25 which proved particularly effective at generating structures for proteins with missing chemical shifts, such as often is encountered for paramagnetic proteins or systems where conformational exchange on the chemical shift time scale causes the absence of signals for residues impacted by such exchange. In the hybrid method, the standard Rosetta procedure is used to select 2000 candidates for each segment; chemical shifts, if available, subsequently narrow this selection down to 200. This approach ensures that for regions that lack chemical shift information, the method still takes advantage of the sophisticated sequence-based fragment selection algorithm of Rosetta. With essentially complete chemical shifts assignments for GA/GB, the hybrid procedure remains nearly as effective as standard Rosetta when using all six types of chemical shifts, despite the fact that it has a much smaller pool (2000 vs. ∼2,000,000) of fragments to pick from, and the majority of this reduced 2000-member set being of the incorrect secondary structure type. On the other hand, when using only 1H chemical shifts as input for this hybrid method, this information is insufficiently discriminating to allow selection of adequate quality fragments from the reduced set and no convergence is obtained for GA95, whereas for GB95 results are comparable to what is obtained with standard Rosetta [Supporting Information Fig. S5(E,F)].

Next to the CHESHIRE and CS-Rosetta chemical-shift-based structure prediction methods, an effective complementary approach named CS23D has been introduced, including a server that allows users to submit chemical shifts and a protein sequence.18 CS23D searches its protein structural database for maximum size fragments (20–200 residues) by matching (1) the amino acid sequence, (2) the chemical shift derived secondary structure, and (3) the chemical shift derived torsion angles of the query protein with those of each protein in the database. CS23D is driven mostly by comparative homology modeling whenever sequence homology is found, but in the absence of homology resorts to Rosetta, utilizing the shift-predicted torsion angles to guide the Rosetta fragment selection. CS23D is orders of magnitude faster than de novo methods such as CHESHIRE or CS-Rosetta when homologous proteins are present in the database. As expected, CS23D proved very effective for GAwt and GBwt, and it remains good for GB88 and GB95, generating converged and correct models that agree as well with the experimental structures as the CS-Rosetta models (Supporting Information Fig. S6; Table S2). However, CS23D returned a poorly folded mostly helical model for GA88 and a GB-type fold for GA95, suggesting that the current parameterization of CS23D can steer it in the wrong direction even when chemical shift evidence for secondary structure is quite clear-cut.

Modeling of a protein structure from sequence alone consists of several steps: finding templates from known structures related to the sequence to be modeled; aligning the sequence with the templates; building the model; and evaluating the model.2 The template selection procedure, which may be performed by sequence comparison methods or by sequence-structure threading, is critical to obtain a well-modeled structure.4 For cases such as those evaluated in this study, which concern proteins with high-sequence identity but a very different tertiary structure, the critical structural information is encoded in just a few nonidentities. In such cases, template selection easily is “tricked” by the high similarity of the sequence profile.

Structural information encoded in NMR chemical shifts is often not unique in that for any given set of chemical shifts it is possible to find multiple backbone conformations that are compatible with such shifts. However, chemical shifts dramatically narrow the region of conformational space, and MFR searching of fragments takes advantage of this information by selecting from its protein structure database those fragments most compatible with its chemical shifts without being “tricked” by sequence similarity. This then provides an efficient way to select the unbiased templates and allows successful modeling of the structures for such proteins. It is interesting to note that very little chemical shift information, even just the values of the 1HN and 1Hα nuclei, suffices to guide CS-Rosetta to the correct structure, at least for small systems such as GA and GB. Our results confirm that de novo chemical shift-based structure determination methods, as exemplified by CHESHIRE and CS-Rosetta, are a robust alternative for predicting structures of small proteins.35

To date, out of more than three dozen proteins evaluated, we have not encountered a single case where a converged CS-Rosetta structure of a monomeric protein deviates significantly from its experimentally determined counterpart. Nevertheless, the question remains whether the CS-Rosetta results should be treated as experimental structures or as predicted models. For the time being, we feel that it remains prudent to validate the correctness of such models by checking a small number of easily accessible long-range backbone–backbone NOEs, and/or simply by comparing the predicted and observed small angle X-ray scattering pattern for such proteins. Such SAXS data can readily and rapidly be obtained using a small fraction of the NMR sample, even using low-intensity in-house X-ray equipment.36

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rosetta@home participants and the BOINC project for contributing computing power.

References

- 1.Burley SK. An overview of structural genomics. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:932–934. doi: 10.1038/80697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingues FS, Lackner P, Andreeva A, Sippl MJ. Structure-based evaluation of sequence comparison and fold recognition alignment accuracy. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:1003–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker D, Sali A. Protein structure prediction and structural genomics. Science. 2001;294:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1065659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das R, Baker D. Macromolecular modeling with Rosetta. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:363–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.062906.171838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srinivasan R, Fleming PJ, Rose GD. Ab initio protein folding using LINUS. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:48–66. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan R, Rose GD. Ab initio prediction of protein structure using LINUS. Protein Struct Funct Genet. 2002;47:489–495. doi: 10.1002/prot.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozkan SB, Wu GA, Chodera JD, Dill KA. Protein folding by zipping and assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Fiser A, Rost B, Sali A. Reliability of assessment of protein structure prediction methods. Structure. 2002;10:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson AR. A folding space odyssey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2759–2760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander PA, He Y, Chen Y, Orban J, Bryan PN. The design and characterization of two proteins with 88% sequence identity but different structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11963–11968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700922104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Y, Chen YH, Alexander P, Bryan PN, Orban J. NMR structures of two designed proteins with high sequence identity but different fold and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14412–14417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805857105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander PA, He Y, Chen Y, Orban J, Bryan PN. A minimal sequence code for switching protein structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21149–21154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowers PM, Strauss CEM, Baker D. De novo protein structure determination using sparse NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 2000;18:311–318. doi: 10.1023/a:1026744431105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavalli A, Salvatella X, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. Protein structure determination from NMR chemical shifts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9615–9620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong HP, Shen Y, Rose GD. Building native protein conformation from NMR backbone chemical shifts using Monte Carlo fragment assembly. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1515–1521. doi: 10.1110/ps.072988407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen Y, Lange O, Delaglio F, Rossi P, Aramini JM, Liu GH, Eletsky A, Wu YB, Singarapu KK, Lemak A, Ignatchenko A, Arrowsmith CH, Szyperski T, Montelione GT, Baker D, Bax A. Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4685–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wishart DS, Arndt D, Berjanskii M, Tang P, Zhou J, Lin G. CS23D: a web server for rapid protein structure generation using NMR chemical shifts and sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:496–502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He YN, Rozak DA, Sari N, Chen YH, Bryan P, Orban J. Structure, dynamics, and stability variation in bacterial albumin binding modules: implications for species specificity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10102–10109. doi: 10.1021/bi060409m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher T, Alexander P, Bryan P, Gilliland GL. 2 Crystal-structures of the B1 immunoglobulin-binding domain of streptococcal protein-G and comparison with NMR. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4721–4729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karplus K, Karchin R, Barrett C, Tu S, Cline M, Diekhans M, Grate L, Casper J, Hughey R. What is the value added by human intervention in protein structure prediction? Protein Struct Funct Genet Suppl. 2001;5:86–91. doi: 10.1002/prot.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meiler J, Muller M, Zeidler A, Schmaschke F. Generation and evaluation of dimension-reduced amino acid parameter representations by artificial neural networks. J Mol Model. 2001;7:360–369. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y, Vernon R, Baker D, Bax A. De novo protein structure generation from incomplete chemical shift assignments. J Biomol NMR. 2009;43:63–78. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kontaxis G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Molecular fragment replacement approach to protein structure determination by chemical shift and dipolar homology database mining. Meth Enzymol. 2005;394:42–78. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)94003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Y, Bax A. Protein backbone chemical shifts predicted from searching a database for torsion angle and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 2007;38:289–302. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito H. Conformation-dependent 13C chemical shifts—a new means of conformational characterization as obtained by high resolution solid state 13C NMR. Magn Reson Chem. 1986;24:835–852. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spera S, Bax A. Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cβ13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gronenborn AM, Filpula DR, Essig NZ, Achari A, Whitlow M, Wingfield PT, Clore GM. A novel, highly stable fold of the immunoglobulin binding domain of streptococcal protein G. Science. 1991;253:657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1871600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian LY, Derrick JP, Sutcliffe MJ, Yang JC, Roberts GCK. Determination of the solution structures of domain-II and domain-III of protein G from streptococcus by 1H NMR. J Mol Biol. 1992;228:1219–1234. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90328-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohl CA, Strauss CEM, Misura KMS, Baker D. Protein structure prediction using rosetta. Meth Enzymol. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Holm A, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N random coil NMR chemical shifts of the common amino acids. I. Investigations of nearest-neighbor effects. J Biomol NMR. 1995;5:67–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00227471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gryk MR, Hoch JC. Local knowledge helps determine protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4533–4534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801069105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons LM, Grishaev A, Bax A. The periplasmic domain of TolR from haemophilus influenzae forms a dimer with a large hydrophobic groove: NMR solution structure and comparison to SAXS data. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3131–3142. doi: 10.1021/bi702283x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]