Abstract

Research on protein oxidative damage may give insight into the nature of protein functions and pathological conditions. In this work, the oxidative damage of bovine insulin on Au electrode was investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV). The experimental results show that there are two anodic peaks for the oxidative damage of bovine insulin, which arise from the oxidation of the exposed disulfide bond S—SCYS7A,CYS7B, forming sulfenic acid RSOH (1.20 V, vs. SCE), sulfinic acid RSO2H and sulfonic acid RSO3H (1.35 V, vs. SCE). These in vitro findings not only demonstrate the applicability of CV in simulating/evaluating the oxidative damage of nonredox proteins but also find two promising candidates (two anodic peaks) for measuring insulin.

Keywords: bovine insulin, oxidative damage, evaluation strategy, cyclic voltammetry

Introduction

The diverse physiological functions of proteins are closely related to their integrated structures.1–4 Once oxidative damage occurs in proteins, their corresponding functions reduce or disappear, thereby inducing aging, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other pathological conditions.5–7 The inherent correlations between the aforementioned diseases and protein oxidative damage have been widely confirmed and have aroused wide attention.1,8–10 Investigation into the oxidative damage mechanism of proteins not only benefits to clarify protein functions, but also contributes to disease diagnosis, prevention and treatment.6,10–12

In evaluation technologies for oxidative damage to proteins, electrochemical technology is sensitive, accurate, selective, simple, clean, and nondestructive.13,14 The direct or indirect electron exchange processes between electroactive components and electrode are similar to the oxidative processes of biomolecules in vivo.14 Therefore, the electrochemical mechanism for the oxidation of proteins is suitable for simulating and explaining the oxidative damage of proteins in vitro and in vivo. With the development of electrochemical apparatus and the application of modified electrodes15 and microelectrodes,16 electrochemical technology has obvious advantages in study of protein oxidative damage.

In previous studies, research mainly focused on redox proteins (iron porphyrin proteins, etc.), and little work was related to the side chain oxidation of amino acids in proteins.17–19 Therefore, a thorough investigation on the processes or mechanisms of protein oxidative damage has a great significance. In this article, an important functional protein of bovine insulin was selected as an oxidative target and its oxidation mechanism on Au electrode was evaluated by CV.

Results and Discussion

Cyclic voltammetry analysis

The cyclic voltammograms of phosphate buffer and bovine insulin are shown in Figure 1. Phosphate buffer (Fig. 1, curve A) has a pair of redox peaks, the anodic peak is at 1.16 V and the cathodic peak is at 0.69 V. Phosphate cannot be oxidized at such low potentials and both peaks are corresponding to the redox processes of Au electrode. The anodic peak arises from the formation of AuOx and the cathodic peak corresponds to the reductive process.20,21 Compared with curve A, bovine insulin (Fig. 1, curve B) has an increased anodic peak near 1.20 V, but a stable cathodic peak near 0.70 V. So this anodic peak should not only be attributed to the electrochemical oxidation of Au electrode but also be assigned to the oxidation of insulin. It is clear that the new anodic peak near 1.35 V corresponds to another oxidation process of bovine insulin. Thus bovine insulin has two irreversible oxidation processes on Au electrode.

Figure 1.

Cyclic voltammograms of phosphate buffer, bovine insulin, and cystine. Conditions: curve A 0.05 mol/L phosphate buffer, curve B 0.1 mmol/L bovine insulin, curve C 0.1 mmol/L cystine; initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5 to 1.6 V; scan rate 100 mV/s; pH = 2.5; temperature 20°C. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

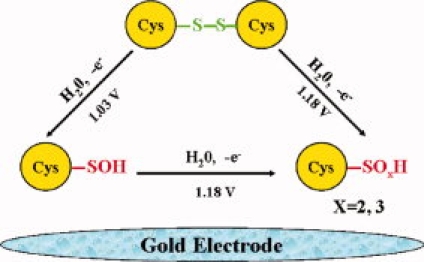

To further investigate the oxidative damage mechanism and determine the damage sites, we scanned all amino acids within insulin under the aforementioned experimental conditions. Specific experimental results (Table I) showed that cystine in bovine insulin was the only potential oxidative site due to its anodic peaks at 1.03 and 1.18 V. The cyclic voltammogram of cystine was also given in Figure 1 curve C. Sample of cystine has a similar cathodic peak to that of phosphate buffer, meaning a stable redox process (a stable anodic peak) for Au electrode. Explanations for the significantly increased anodic peak (near 1.18 V) and the new coming anodic peak (near 1.03 V) are the newly formed products. Under the same conditions, glycine has not been oxidized, which means that carboxyl and amino groups can not be oxidized. Therefore, the oxidative site of cystine is limited to its S—S bond. The oxidation mechanism of cystine has been clarified and it can be oxidized into sulfenic acid in a free manner but hard to be oxidized into sulfinic acid or sulfonic acid.22 So the oxidation of cystine on working electrode can occur by the following mechanisms:

Table I.

Electrochemical Characteristic of Insulin-Containing Amino Acids

| Amino acids (0.1 mmol/l) | Structural groups | Anodic peaks |

|---|---|---|

| Cystine | Sulfur containing amino acids | 1.03 V, 1.18 V |

| Phe, Tyr | Aromatic amino acids | None |

| Gly, Val, Leu, Ile, Glu, Pro, Ala | Aliphatic amino acids | |

| Lys, Arg, Gln, Asn, His | Amide containing amino acids | |

| Ser, Thr | Hydroxyl containing amino acids |

The anodic peak of cystine near 1.18 V is much higher than that of phosphate buffer, suggesting new oxidation product formed; the anodic and cathodic peaks of other amino acids are close to that of phosphate buffer, thus these peaks should be attributed to the redox processes of Au electrode.

Conditions: initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5–1.6 V; scan rate 100 mV/s; pH = 2.50; temperature 20°C.

Scheme 1.

[Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

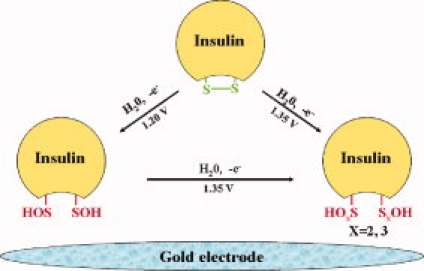

By comparing structures of bovine insulin and cystine, it can be concluded that disulfide bonds (S—S, part of cystine) in insulin are the candidates of oxidative damage sites. At the same time, the oxidative damage processes of insulin and cystine both include two irreversible processes. However, due to steric hindrance, the oxidative damage of cystine can be achieved under lower potentials. Thus the oxidative damage mechanism for insulin is as follow:

Scheme 2.

[Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

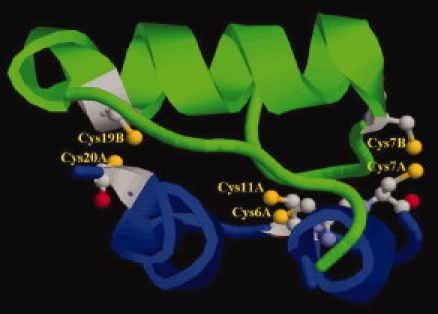

Bovine insulin has three disulfide bonds (S—SCYS7A-CYS7B, S—SCYS6A-CYS11A, and S—SCYS20A-CYS19B), implying three candidates that can be oxidized in electrochemical processes. The structure and the cystine of bovine insulin are shown in Figure 2. But they have different surface areas (Fig. 2), thus the relative degree of oxidative damage is different. By comparing the solvent accesible surface areas (SASA) of these disulfide bonds within insulin using the GETAREA 1.1 software, the oxidation order can be evaluated. The results show in Table II. From Table II, we can see that S—SCYS6A-CYS11A or S—SCYS20A-CYS19B has small solvent accesible surface areas and can not be oxidized. Thus the damage site within insulin is only S—SCYS7A-CYS7B.

Figure 2.

Structure of disulfide bonds in bovine insulin Chain A: Blue; Chain B: Green; Cystines are in the state of ball and stick. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Table II.

SASA of Disulfide Bonds in Bovine Insulin

| Atoms | S—SCYS7A,CYS7B | S—SCYS6A,CYS11A | S—SCYS20A,CYS19B |

|---|---|---|---|

| SASA of Disulfide bonds (Å2) | 37.36 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Oxidation order | S—SCYS7A,CYS7B > S—SCYS6A,CYS11A ≈ S—SCYS20A,CYS19B | ||

The 3-D structural data of bovine insulin gets from Protein Data Bank and its PDB code is 1B18.

The influences of dissolved oxygen, scan rate, pH, and temperature on the oxidative damage processes

Influence of dissolved oxygen

With vacuum deaeration, the anodic peak potentials shift negatively and their currents increase markedly (Table III), meaning dissolved O2 has adverse influence on the oxidation process of insulin. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that dissolved O2 tends to adhere to the electrode and block the oxidation of insulin and Au electrode.23 To get reliable and steady results, all samples should be degassed before the scan.

III.

The Influence of Dissolved Oxygen

| Potentials/mV |

Currents/10−7A |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak a | Peak b | Peak a | Peak b | |

| Without vacuum disposal | 1090 | 1250 | 860 | 1403 |

| With vacuum disposal | 1110 | 1286 | 1110 | 1850 |

| Rate of increase | 1.83% | 2.89% | 24.72% | 31.86% |

Conditions: Bovine insulin 0.1 mmol/L; initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5 to 1.6 V; scan rate 100 mV/s; pH = 2.50; temperature 20°C.

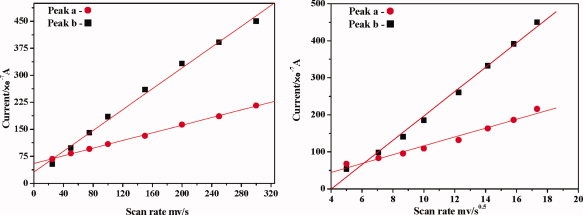

Influence of scan rate

Relations between scan rate and anodic peak currents are in favor of determining the control steps of oxidative damage. The influence of scan rate on bovine insulin anodic peaks is discussed here (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The influence of scan rate. Conditions: Bovine insulin 0.1 mmol/L; initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5 to 1.6 V; pH = 2.5; temperature 20°C. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

The currents of anodic peaks and v1/2 have a linear relationship. For example, the linear regression curve of anodic peak a is ia = −3.47 + 11.96 v1/2 (i: 10−7 A, v: mV/s, R = 0.9873) and that of peak b is ib = −132.5 + 32.93 v1/2 (i: 10−7 A, v: mV/s, R = 0.9965). We also find that there is a linear relationship between peak currents and scan rate. Taking peak a as an example, the linear regression curve is ia = 55.1 + 0.53 v (i: 10−7 A, v: mV/s, R = 0.9995). For peak b, the linear regression curve is ib = 31.12 + 1.45 v (i: 10−7 A, v: mV/s, R = 0.9971). When these processes are controlled by either diffusion or adsorption, all linear regression curves should go through the origin point. In fact, the x-intercepts and y-intercepts of these curves are not zero. So we can conclude that the oxidative damage of bovine insulin is synchronously controlled by diffusion and adsorption.

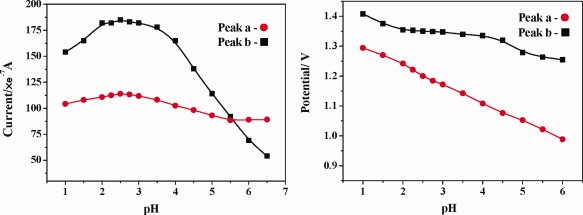

The influence of pH

The influence of pH on anodic peaks is shown in Figure 4. The currents of both anodic peaks are stable between 2 and 3.5 and reach the maximum signals near 2.5. The potentials of both peaks are decreased with a higher pH. But due to the influence of electrode oxidation, peak a has a more pronounced downward trend. So pH 2.5 was chosen as a suitable experimental condition.

Figure 4.

The influence of pH. Conditions: Bovine insulin 0.1 mmol/L; initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5 to 1.6 V; scan rate 100 mV/s; temperature 20°C. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

These results are due to the structural changes of insulin. When pH is lower than its isoelectric point (5.25–5.35), insulin is positively charged. It is difficult for insulin to migrate to the negatively charged working electrode (positive scan), resulting in the reduction of peak currents. At the same time, with the increase of pH, insulin gradually formed polymers and will hinder the processes of electrochemical oxidation.24

The influence of temperature

Temperature has a complicated influence on the anodic peaks (Fig. 5). When temperature increases from 5 to 45°C, both peaks gradually shift in negative direction and have increased currents. A higher temperature can promote the diffusion of bovine insulin, thus enhancing the oxidative processes on working electrode.14 This result is consistent with the diffusion-controlled oxidative processes occurring at the working electrode. But when the temperature is lower than 5°C, they have obviously increased currents and decreased potentials. The mainspring for the increased currents is the degeneration of bovine insulin, which can increase the contact area of water and disulfide bonds, finally is in favor of the oxidative damage processes.

Figure 5.

The influence of temperature. Conditions: Bovine insulin 0.1 mmol/L; initial potential −0.5 V; scan range −0.5 to 1.6 V; scan rate 100 mV/s; pH = 2.5. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

In summary, cyclic voltammetry was shown to be well suited for simulating and evaluating the oxidative damage processes of bovine insulin. These processes were compared with that of phosphate buffer and cystine and all related amino acids within insulin. The influences of dissolved oxygen, pH, scan rate, temperature were also investigated in detail. Experimental results prove that the disulfide bonds within bovine insulin are the target of electro-oxidation and the oxidative products are sulfenic acid RSOH, sulfinic acid RSO2H, and sulfonic acid RSO3H. But due to steric hindrance, the oxidative damage to insulin requires more stringent conditions than that of cystine (free disulfide). The electrochemical processes are not only controlled by adsorption and diffusion but also obviously affected by dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature. These new findings will give clues for understanding the mechanisms of oxidative damage to bovine insulin and other nonredox proteins.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and apparatus

Asparagine, arginine, bovine insulin, cystine, glycine, glutamic acid, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, praline, phenylalanine, serine, tyrosine, threonine, tryptophan, valine (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co.); H2SO4, H3PO4 (Tianjin Tianda Chemical Reagent Co.); 30% H2O2, Ethanol, (Tianjin Guangcheng Chemical Reagent Co.). All reagents are analytical reagents or biochemical reagents and prepared with ultrapure water. All experiments were carried out on a CHI 802B electrochemistry workstation equipped with a standard tri-electrode system. And it was composed by a CHI101 Au working electrode, a saturated calomel reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode. The phosphate buffers were prepared using a pHs-3C acidity meter (Shanghai Pengshun Scientific Instrument Co.). Samples were degassed in a 2XZ-0.5 vacuum pump and stored in a vacuum desiccator. An electric-heated thermostatic water bath (Jiangsu Jintan Instrument Co.) was used for temperature control.

Pretreatment of Au electrode

To ensure the reproducibility and stability of experimental results, the pretreatment of working electrode is essential. Before each experiment, the Au electrode was polished with a fine sand paper (0.25 mm) and Al2O3 powers (1 μm, 0.3 μm, and 0.05 μm, successively), rinsed with ultrapure water, and dipped into Piranha solution for 10 mins. After rinsing with ultrasonic in ultrapure water and ethanol, the electrode was preserved in ethanol.

Experiment method

Series of phosphate buffers were prepared by adding 0.05 mol Na2HPO4 into 0.05 mol H3PO4. Quantitative insulin was weighed up and added into phosphate buffers. After deoxidized with a vacuum pump, the samples were scanned in a tri-electrode cell. Idiographic experiment conditions (temperature, pH, scan rate, and scan range) are described in Results and Discussion section.

References

- 1.Davies MJ. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;17:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naganathan AN, Doshi U, Fung A, Sadqi M, Muoz V. Dynamics, energetics, and structure in protein folding. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8466–8475. doi: 10.1021/bi060643c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prentiss MC, Hardin C, Eastwood MP, Zong C, Wolynes PG. Protein structure prediction: the next generation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:705–716. doi: 10.1021/ct0600058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu RT, Sun F, Zhang LJ, Zong WS, Zhao XZ, Wang L, Wu RL, Hao XP. Evaluation on the toxicity of nanoAg to bovine serum albumin. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:4184–4188. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20313–20316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean RT, Fu S, Stocker R, Davies MJ. Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochem J. 1997;324:1–18. doi: 10.1042/bj3240001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suresh S. Biomechanics and biophysics of cancer cells. Acta biomater. 2007;3:413–438. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller RJ, Halmes NC, Hinson JA, Pumford NR. Immunochemical detection of oxidized proteins. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:430–433. doi: 10.1021/tx00034a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stadtman ER, Berlett BS. Reactive Oxygen-mediated protein oxidation in aging and disease. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:485–494. doi: 10.1021/tx960133r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Requena JR, Levine RL, Stadtman ER. Recent advances in the analysis of oxidized proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donne ID, Scaloni A, Giustarini D, Cavarra E, Tell G, Lungarella G, Colombo R, Rossi R, Milzani A. Proteins as biomakers of oxidative/nitrosative stress in diseases: the contribution of redox proteomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:55–99. doi: 10.1002/mas.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst A, McIlwain S, Schmidt JJ, Aiken JM, Page CD, Li L. Prion disease diagnosis by proteomic profiling. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1030–1036. doi: 10.1021/pr800832s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Privett BJ, Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Electrochemical sensors. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4499–4517. doi: 10.1021/ac8007219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zong WS, Liu RT, Zhao LZ, Tian YM, Yuan D, Gao CZ. Side-chain oxidative damage to cysteine on a glassy carbon electrode. Amino Acids. 2009;37:559–564. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong FA, Hill HAO, Walton NJ. Direct electrochemistry of redox proteins. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:407–413. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tibbon SM, Katz E, Willner I. Chiral Recognition in Mediated Electron Transfer in Redox Proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9925–9926. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng X, Bruckenstein S. Polycrystalline gold electrode redox behavior in an ammoniacal electrolyte Part I. A parallel RRDE, EQCM, XPS and TOF-SIMS study of supporting electrolyte phenomena. J Electroanal Chem. 1999;461:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le'ger C, Bertrand P. Direct electrochemistry of redox enzymes as a tool for mechanistic studies. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2379–2438. doi: 10.1021/cr0680742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendes RK, Ferreira DCM, Carvalhal RF, Peroni LA, Stach-Machadob DR, Kubota LT. Development of an electrochemical immunosensor for phakopsora pachyrhizi detection in the early diagnosis of soybean rust. J Braz Chem Soc. 2009;20:795–801. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih Y, Zen JM, Kumar AS, Chen PY. Flow injection analysis of zinc pyrithione in hair care products on a cobalt phthalocyanine modified screen-printed carbon electrode. Talanta. 2004;62:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giger K, Vanam RP, Seyrek E, Dubin PL. Suppression of insulin aggregation by heparin. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2338–2344. doi: 10.1021/bm8002557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu G, Chance MR. Radiolytic modification of sulfur-containing amino acid residues in model peptides: fundamental studies for protein footprinting. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2437–2449. doi: 10.1021/ac0484629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tkac J, Davis JJ. An optimised electrode pre-treatment for SAM formation on polycrystalline gold. J Electroanal Chem. 2008;621:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryant C, Spencer DB, Miller A, Bakaysa DL, McCune KS, Maple SR, Pekar AH, Brems DN. Acid Stabilization of Insulin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8075–8082. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]