Abstract

Gremlin, a cell growth and differentiation factor, promotes the development of diabetic nephropathy in animal models, but whether GREM1 gene variants associate with diabetic nephropathy is unknown. We comprehensively screened the 5` upstream region (including the predicted promoter), all exons, intron-exon boundaries, complete untranslated regions, and the 3` region downstream of the GREM1 gene. We identified 31 unique variants, including 24 with a minor allele frequency exceeding 5%, and 9 haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNPs). We selected one additional variant that we predicted to alter transcription factor binding. We genotyped 709 individuals with type 1 diabetes of whom 267 had nephropathy (cases) and 442 had no evidence of kidney disease (controls). Three individual SNPs significantly associated with nephropathy at the 5% level, and two remained significant after adjustment for multiple testing. Subsequently, we genotyped a replicate population comprising 597 cases and 502 controls: this population supported an association with one of the SNPs (rs1129456; P = 0.0003). Combined analysis, adjusted for recruitment center (n = 8), suggested that the T allele conferred greater odds of nephropathy (OR 1.69; 95% CI 1.36 to 2.11). In summary, the GREM1 variant rs1129456 associates with diabetic nephropathy, perhaps explaining some of the genetic susceptibility to this condition.

There is substantial epidemiologic evidence supporting genetic susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy; however, compelling replication of genetic risk factors in multiple white populations has proved difficult.1 The development of larger carefully phenotyped case-control collections now permits appropriately designed studies to be conducted with improved statistical power.2,3

Gremlin is implicated in several developmental pathways4,5 and has become increasingly recognized as an important contributor to renal disease.6–8 Gremlin influences cell growth and differentiation,9 particularly through bone morphogenic protein and transforming growth factor-β-mediated processes.4,10 We originally reported elevated Gremlin mRNA in mesangial cells subjected to high extracellular glucose11 and cyclic mechanical strain in vitro.10 Increased expression of GREM1 has been observed in animal models of kidney disease,12 including in the renal cortex of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes and nephropathy.10 Gremlin mRNA levels correlate with serum creatinine and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy.13 Gremlin is a major bone morphogenic protein antagonist,14 gremlin expression is increased during the development of diabetic nephropathy,15 and the increased glomerular basement membrane thickening and microalbuminuria associated with diabetic kidney disease are attenuated in diabetic GREM1± mice.16 Increased levels of GREM1 expression have been observed in renal biopsies from patients with diabetic nephropathy,17 chronic allograft nephropathy,18 and GN.19

The GREM1 gene is gremlin 1 homolog, cysteine knot superfamily (Xenopus laevis), previously known as IHG-2, DRM, gremlin, DAND2, PIG2, or CKTSF1B1. We have comprehensively screened the GREM1 gene for genetic variants and investigated common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for association with diabetic nephropathy.

Results

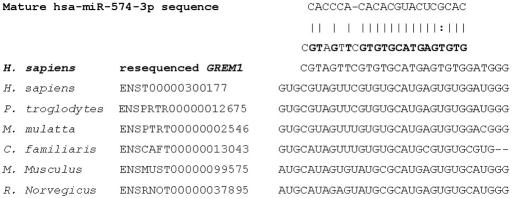

Individuals have been described previously in case-control association studies investigating diabetic nephropathy2; characteristics are presented in Table 1. Resequencing data were submitted to GenBank as (1) DQ100069 Gremlin 1 homolog, cysteine knot superfamily (X. laevis) (GREM1) 5′ upstream, promoter and exon 1, genomic sequence; and (2) DQ100070 Gremlin 1 homolog, cysteine knot superfamily (X. laevis) (GREM1) coding region and 3′ downstream genomic sequence. WAVE (denaturing HPLC) screening and bidirectional resequencing of 9163 bp identified 31 unique variants that were submitted to dbSNP (ss48297764 to ss48297794). Eleven SNPs were novel and 24 were observed with a minor allele frequency (MAF) >5%. The position of each SNP was mapped to the current reference sequence for the genomic contig and mRNA (Table 2). MAFs were established in 48 control individuals from the Young Hearts collection20; the minimum observed MAF was 10.6% (Table 2). Linkage disequilibrium was calculated for the 23 biallelic SNPs with MAF >5% and 12 major haplotypes (with estimated frequency >2%) were identified by snphap, which jointly accounted for 80% of haplotypic variation (Figure 1). Six haplotypes were observed with MAF >5% (Figure 1b). On the basis of this haplotype structure, nine haplotype-tagging SNPs (htSNPs) were identified to comprehensively investigate all common variation in the GREM1 gene; mean r2 between SNPs included in the haplotype was 0.90 (minimum r2 = 0.73).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of genotyped populations

| Characteristic | All-Ireland Collection |

U.K. Collection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |

| Number of individuals | 267 | 442 | 597 | 502 |

| Gender (% male) | 57.3 | 40.0 | 59.3 | 44.2 |

| Age at recruitment (years)a | 48.7 ± 11.6 | 42.2 ± 11.7 | 48.5 ± 10.1 | 44.9 ± 11.2 |

| Age at diagnosis (years)a | 16.7 ± 8.5 | 15.0 ± 8.1 | 14.5 ± 7.6 | 15.6 ± 8.0 |

| Duration of diabetes (years)a | 32.0 ± 9.6 | 27.2 ± 9.3 | 33.9 ± 9.3 | 29.2 ± 9.1 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%)a | 10.6 ± 1.5 | 9.5 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 8.2 ± 1.4 |

aData are mean ± SD.

Table 2.

Reference location for submitted SNPs based on WAVE analysis and SNP confirmationa

| NCBI Unique SNP Identifier | GenBank Accession | NCBI Unique Assay Identifier ss# | Location on Reference Genomic Contig and mRNA | MAFb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs35529564 | DQ100069 | 48297764 | NT_010194.16:g0.3799002delA | Multiallelic |

| rs35285486 | DQ100069 | 48297765 | NT_010194.16:g0.3799426C>T | NA |

| rs3812934 | DQ100069 | 48297766 | NT_010194.16:g0.3799427T>C | 50.0 |

| rs1406389 | DQ100069 | 48297767 | NT_010194.16:g0.3800035A>T | 15.2 |

| rs1919364 | DQ100069 | 48297768 | NT_010194.16:g0.3800131C>G | 45.6 |

| rs35531317 | DQ100069 | 48297769 | NT_010194.16:g0.3800809C>G; NM_013372.5:c.−112C>G | NA |

| rs2293582c | DQ100069 | 48297770 | NT_010194.16:g0.3800969G>A; NM_013372.5:c.−2+50G>A | 24.4 |

| rs3207357c | DQ100069 | 48297771 | NT_010194.16:g0.3801040T>C; NM_013372.5:c.−2+121T>C | 14.4 |

| rs2293581 | DQ100069 | 48297772 | NT_010194.16:g0.3801293G>A; NM_013372.5:c.−2+374G>A | NA |

| rs28617440 | DQ100070 | 48297773 | NT_010194.16:g0.3811436T>C; NM_013372.5:c.−1−2012T>C | NA |

| rs16973303 | DQ100070 | 48297774 | NT_010194.16:g0.3811485T>G; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1963T>G | 30.7 |

| rs7178059 | DQ100070 | 48297775 | NT_010194.16:g0.3811917C>G; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1531C>G | NA |

| rs28433691 | DQ100070 | 48297776 | NT_010194.16:g0.3811947A>G; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1501A>G | 44.6 |

| rs35566180 | DQ100070 | 48297777 | NT_010194.16:g0.3811949delT; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1499delT | 44.8 |

| rs7182522 | DQ100070 | 48297778 | NT_010194.16:g0.3812024C>T; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1424C>T | 13.0 |

| rs34722587 | DQ100070 | 48297779 | NT_010194.16:g0.3812057T>C; NM_013372.5:c.−1−1391T>C | NA |

| rs35943942 | DQ100070 | 48297780 | NT_010194.16:g0.3812612insA; NM_013372.5:c.−1−835insA | 32.6 |

| rs35330276 | DQ100070 | 48297781 | NT_010194.16:g0.3812647G>A; NM_013372.5:c.−1−801G>A | 20.2 |

| rs11854391 | DQ100070 | 48297782 | NT_010194.16:g0.3813139A>T; NM_013372.5:c.−1−309A>T | 33.7 |

| rs12915554 | DQ100070 | 48297783 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814043C>A; NM_013372.5:c.*40C>A | 30.2 |

| rs33963919 | DQ100070 | 48297784 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814227C>T; NM_013372.5:c.*224C>T | 31.8 |

| rs17816260 | DQ100070 | 48297785 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814242A>C; NM_013372.5:c.*239A>C | 32.6 |

| rs3743105 | DQ100070 | 48297786 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814508T>C; NM_013372.5:c.*505T>C | 31.8 |

| rs3743104 | DQ100070 | 48297787 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814542A>G; NM_013372.5:c.*539A>G | 33.0 |

| rs34498321 | DQ100070 | 48297788 | NT_010194.16:g0.3814993T>G; NM_013372.5:c.*990T>G | NA |

| rs7162202 | DQ100070 | 48297789 | NT_010194.16:g0.3815012T>G; NM_013372.5:c.*1009T>G | 37.5 |

| rs17228641 | DQ100070 | 48297790 | NT_010194.16:g0.3815365G>A; NM_013372.5:c.*1362G>A | 11.7 |

| rs3743103 | DQ100070 | 48297791 | NT_010194.16:g0.3816184C>T; NM_013372.5:c.*2181C>T | 45.0 |

| rs10318c | DQ100070 | 48297792 | NT_010194.16:g0.3816536C>T; NM_013372.5:c.*2533C>T | 19.3 |

| rs1129456 | DQ100070 | 48297793 | NT_010194.16:g0.3817224A>T; NM_013372.5:c.*3221A>T | 10.6 |

| rs7176378 | DQ100070 | 48297794 | NT_010194.16:g0.3817736T>A | 27.4 |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; NA, not applicable.

aThe location of SNPs are provided in relation to the reference assembly of genomic contig (NT_010194) and reference mRNA for Gremlin (NM_013372.5), which was updated on June 28, 2009.

bMAF is based on 96 chromosomes that were resequenced where WAVE suggested a MAF > 5%.

cPutatively functional.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium at the Grem1 locus. (a) Relationship between 23 biallelic SNPs resequenced in 48 control individuals from the Young Hearts collection. Pairwise comparisons where r2 = 0 (no correlation) are highlighted in white through a gray spectrum to black, where r2 = 1 (perfect correlation) for SNPs that are perfect proxies for each other. (b) Major haplotypes identified from snphap.

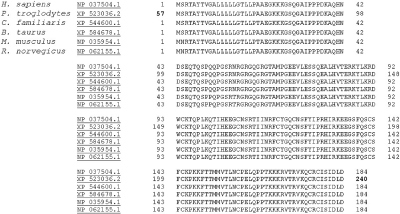

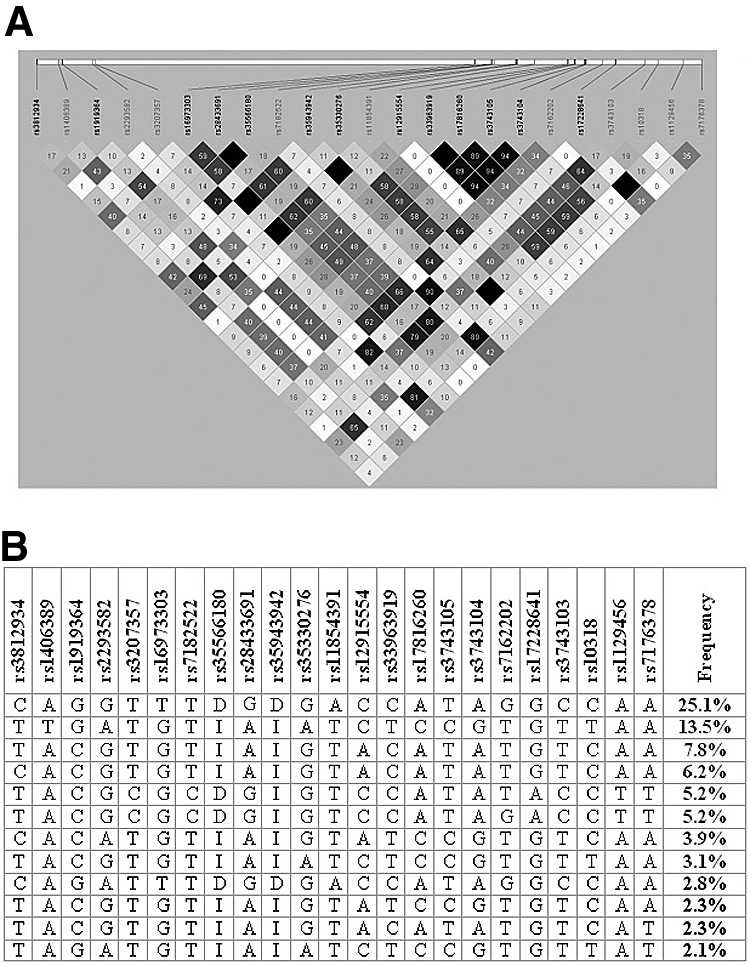

One of the htSNPs (rs2293582) overlapped with promoter prediction PI014696 and was predicted to generate a new binding site V$ETSF/GABP.01. An additional SNP, rs3207357, was selected for further genotyping because it was also associated with promoter prediction PI014696 and may affect transcription factor binding where T > C putatively influences the V$E2FF/E2F.01 site. In silico investigation using UTRScan21 (accessed July 16, 2009) revealed two elements of interest, the K-box and the GY-box. Searching the major database for microRNA information (miRBase)22 (accessed July 6, 2009) highlighted a target site for microRNA 574 (MIR574 gene) at NM_013372.5:c.*141 (Figure 2). No variants were identified in the protein coding region, and comparison of protein sequences in six species reveals 100% conservation for the 184 amino acids that comprise Homo sapiens GREM1 protein (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Interrogation of miRBase highlighted a computationally predicted target site. The sequence of miRNA hsa-miR-574-3p is aligned to our resequenced data for the GREM1 gene with alignment across six species, demonstrating a high degree of conservation at this loci.

Figure 3.

In silico, multiple alignment of protein sequences encoded by the GREM1 gene in six species. The comparison reveals strong conservation across the amino acids comprising the H. sapiens GREM1 protein

In the Irish collection (267 cases and 442 controls) association was observed with three SNPs (rs1129456, rs3207357, rs7182522) and diabetic nephropathy at the 5% level of significance (Table 3). After adjustment for recruitment center and multiple comparisons, statistically significant association remained for two SNPs rs1129456 (P = 0.0005, Pcorrected < 0.005) and the putatively functional rs3207357 (P = 0.006, Pcorrected < 0.05). Genotyping in the U.K. collection (597 cases and 502 controls) supported the original association with rs1129456 (P = 0.0003). Logistic regression analysis of the combined data, with adjustment for any potential confounding effect of collection, was first used to fit a general genotypic model. Relative to the reference AA genotype, this model gave estimates of odds ratio (OR) = 1.47 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.16 to 1.87] for the AT genotype and OR = 2.78 (95% CI 1.24 to 6.12) for the TT genotype. However, further analysis revealed that an additive model provided a better fit to the data [Akaike's information criterion (AIC) = 2252.9] than a recessive model (AIC = 2268.6), a dominant model (AIC = 2255.4), or a genotypic model (AIC 2254.7) with an approximately 70% estimated increase in risk associated with each rs1129456 T allele (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.11). Logistic regression of rs1129456 per T allele with adjustment for any potential confounding effect of collection [recruitment center (n = 8), gender, age, and duration of diabetes] showed the following results: all Ireland, OR = 1.68 (95% CI 1.17 to 2.41); United Kingdom, OR = 1.61 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.18); and heterogeneity test (P = 0.82) combined data set, OR = 1.62, (95% CI 1.29 to 2.04). Over transmission of the T allele (25 versus 16) was observed from parents to 124 affected probands (P = 0.16).

Table 3.

Genotype counts in all-Ireland DNA collection and P values for χ2 tests for trend in Irish and U.K. collections (most significant SNPs shown first)a

| SNP (bp position) | Called Genotypes | All-Ireland DNA Collection |

Ptrend Valueb (corrected) | U.K. DNA Collection |

Ptrend Valueb (one-sided) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases Nmax = 267 Count (%) | Controls Nmax = 442 Count (%) | Cases Nmax = 597 Count (%) | Controls Nmax = 502 Count (%) | ||||

| rs1129456c | AA/AT/TT | 192/66/6 | 363/72/4 | 0.0005 | 448/132/15 | 406/90/5 | 0.0003 |

| (3817224) | (73/25/2) | (83/16/1) | (<0.005) | (75/22/3) | (81/18/1) | ||

| rs3207357 | TT/TC/CC | 200/61/5 | 366/65/6 | 0.006 | 456/126/14 | 387/107/5 | 0.08 |

| (3801040) | (75/23/2) | (84/15/1) | (<0.05) | (77/21/2) | (78/21/1) | ||

| rs7182522 | TT/TC/CC | 199/59/3 | 366/65/6 | 0.02 | |||

| (3812024) | (76/23/1) | (84/15/1) | (0.2) | ||||

| rs3743103 | TT/TC/CC | 71/134/54 | 148/194/81 | 0.08 | |||

| (3816184) | (27/52/21) | (35/46/19) | |||||

| rs11854391 | TT/TA/AA | 117/120/30 | 220/171/50 | 0.23 | |||

| (3813139) | (44/45/11) | (50/39/11) | |||||

| rs1406389 | AA/TA/TT | 160/95/10 | 278/152/9 | 0.25 | |||

| (3800035) | (60/36/4) | (63/35/2) | |||||

| rs7162202 | TT/TG/GG | 124/121/20 | 231/170/39 | 0.37 | |||

| (3815012) | (47/46/7) | (52/39/9) | |||||

| rs7176378 | AA/AT/TT | 144/104/16 | 249/158/27 | 0.52 | |||

| (3817736) | (56/39/6) | (58/36/6) | |||||

| rs10318 | CC/CT/TT | 163/90/9 | 275/146/12 | 0.64 | |||

| (3816536) | (62/34 /3) | (63/34/3) | |||||

| rs2293582 | GG/GA/AA | 180/72/10 | 290/126/15 | 0.76 | |||

| (3800969) | (69/27/4) | (67/29/4) | |||||

aSNP position in genomic base pairs is recorded in parentheses below each unique SNP identifier.

bSignificance values presented after adjusted for recruitment center.

cLogistic regression of rs1129456 per T allele, adjusted for recruitment center. All-Ireland collection: OR = 1.80 (95% CI 1.28 to 2.52); U.K. collection: OR = 1.62 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.16); heterogeneity test P = 0.66, combined data set adjusted for recruitment center (n = 8): OR = 1.69 (95% CI 1.36 to 2.11).

Discussion

Gremlin is a strong biologic candidate gene for involvement in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. More than 9 kb of genomic sequence encompassing the GREM1 gene were screened to identify genetic variants. The mRNA and computationally translated sequence agrees 100% with the GenBank protein NP_037504. All resequencing data were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers DQ100069 (2407 bp) and DQ100070 (6756 bp). Thirty-one SNPs were identified, mapped to the genomic (NT_010194.16) and mRNA (NM_013372.5) reference sequences, and submitted to dbSNP to facilitate further study of the GREM1 gene.

No SNPs were observed in protein coding region of GREM1. This is not surprising because there is a high degree of conservation in the 184 amino acids that comprise the human GREM1 protein. Several homologues were identified with 100% conservation noted between amino acids in the human protein compared with chimpanzee, dog, cow, rat, and mouse sequences. In silico evaluation of SNPs revealed two with putative functionality where they overlapped with a computationally predicted promoter. Although individual binding sites predicted in a promoter region are insufficient to indicate transcriptional function, we selected both of these SNPs for further genotyping. It is possible that other elements in the promoter region contribute to the expression of GREM1. Methylation is a key epigenetic feature of DNA that plays an important role in chromosomal integrity and regulation of gene expression. Global DNA hypermethylation from peripheral blood leukocytes of individuals with ESRD has been associated with increased mortality.23 CpG islands are evident for GREM1,24 and GREM1 expression in epithelial cells is lost through methylation in several forms of cancer25 (http://matrix.ugent.be/temp/static/GREM1.html). The investigation of three CpG islands showed hypomethylation of GREM1 before and after induction of chondrogenesis, despite a decrease in expression.26

In silico exploration of the extensive 3′ untranslated region (UTR) suggests several variants that may regulate GREM1. Submitting the 3′ UTR sequence to UTRscan21 identified three matches with two functional elements from patterns defined in the UTRsite collection. Conserved 3′ UTR sequence motifs were observed; the K-box sequence (CTGTGATT) matched once whereas the GY-box (GTCTTCC) matched twice in our resequenced data. Posttranscriptional regulation by these elements is proposed to involve the formation of RNA-RNA duplexes with complementary sequences at the 5′ end of microRNAs.27 Interestingly, the K-box motif was originally identified in Notch pathway target genes encoding basic helix-loop-helix repressors, and the GY-box is common to many of the same Notch pathway target genes.27 Increased expression of Notch pathway genes, concurrently with Gremlin, has been reported for diabetic nephropathy,14 and Notch has been recently suggested as a new therapeutic target for kidney disease.28,29 MicroRNAs are relatively abundant as small RNAs that target transcripts of protein-coding genes and destabilize mRNA or cause translational repression.30 Interrogation of miRBase19 highlighted a computationally predicted target site, conserved across many species, for microRNA 574 at NM_013372.5:c.*141. Possible target sites were also postulated for microRNA 556 (ATCGTGGTTATAGTCAGCTCATT, NM_013372.5:c.*1041) and microRNA 633 (TCATACCTATTAA; NM_013372.5:c.*2527). rs10318 is located within the target sequence for miR633 and rs7162202 resides 31 bp upstream of miR556. rs10318 and rs7162202 were investigated for association with diabetic nephropathy.

GREM1 has been mapped to human chromosome 15q13-q1531 and the sequence position in the current genome build is 15q13.3. MAFs for all common, biallelic SNPs (n = 23) were established based on 96 chromosomes in a general control population. Twelve common haplotypes were identified and the haplotype structure was then used to select nine htSNPs (mean r2 = 0.90) that would survey all common variation. Comparison of our resequenced data with those available in HapMap32 (accessed July 6, 2009) reveals that HapMap is not optimal to investigate GREM1 variants because less than half of resequenced common SNPs in our study are recorded in this resource, and only one is located within the first 12.5 kb. Our results also indicate that the current version of dbSNP would have been of limited utility for linkage disequilibrium mapping because not all common haplotypes could be defined.

Standard quality control measures were good, including genotype distributions for all SNPs in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P > 0.001). Phenotypic and environmental heterogeneity may contribute to individual differences within a resource.33 Covic and colleagues have suggested that, “careful phenotyping requires a large recruitment effort but is necessary to reduce population heterogeneity, a strategy that increases the likelihood of identifying diabetic nephropathy loci”.34 Population heterogeneity was minimized by carefully using comparable phenotypes in both populations, and strict inclusion criteria were used for both collections. To minimize confounding ethnic differences in allele frequencies we selected only third-generation white individuals born in the British Isles for genotyping in this study. No significant genetic heterogeneity was observed in this project; tests for heterogeneity based on genotype data between the original and replicate populations were NS (P = 0.7 adjusted for recruitment center and P = 0.8 considering the maximum potential variables).

Statistically significant association was observed with three SNPs, two of which (rs1129456 and rs3207357) maintained significance after adjustment for multiple testing. rs1129456 is located in the 3′ UTR, 177 bp upstream of the poly(A) signal. The variants adjacent to rs1129456 were both genotyped as htSNPs; however, allele frequencies were similar in case and control groups for these SNPs. The associated SNP rs1129456 was correlated (81%) with the putatively functional SNP rs3207357; however, there were no statistically significant differences observed between replicate case and control groups for this variant. It is possible that a larger replicate collection would support the original association with rs3207357; however, our data suggest that this is not the primary functional variant associated with diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. It is plausible that rs1129456 is in linkage disequilibrium with more distal regulatory elements for the GREM1 gene. The initial association detected at rs1129456 with the Irish collection was replicated in a U.K. population with similar phenotypic criteria. A similar, significant trend was observed in both collections, and combining data (adjusted for recruitment center, gender, age at recruitment, and duration of diabetes) generated a highly significant test for trend (P = 0.00004) and an approximately 60% estimated increase in risk associated with the rs1129456 T allele (OR = 1.62, 95% CI 1.29 to 2.04). Additionally, we have performed a family-based test of association that is not sensitive to population substructure. Although this family collection was underpowered (n = 124 trios) to identify an association, the results do support our case-control findings and reveal an overtransmission of the risk allele (T allele = 61%).

Genetic variants in the GREM1 gene were recently examined in 39 Mexican-American families with type 2 diabetes in which less than 100 individuals had albuminuria.35 No association was reported with urinary albumin:creatinine ratio; however, a weak association was observed with estimated GFR (SNP14, P = 0.01; SNP16, P = 0.049).35 On the basis of their resequencing data (Dr. Farook Thameem, personal communication), neither of these two variants were observed during our screening phase. Interestingly, these variants are adjacent to the SNP (rs1129456) that we observed to be associated with diabetic nephropathy. It should be noted that the base position of variants reported by Thameem and colleagues35 are different from those observed in our study and validated in dbSNP. To the best of our knowledge, no other group has published results evaluating variants in the GREM1 gene with kidney disease phenotypes.

The GREM1 gene initiates and maintains important activities during development and disease processes. However, GREM1 does not work in isolation and it is possible that screening related genes may provide further meaningful associations with kidney disease. We have examined the proximal genetic region surrounding GREM1, but it is possible that this gene is regulated by the interaction of several more distal control regions.36 For example, genetic variation in the LMBR1 gene directly regulates expression of SHH, which is located approximately 1 Mb distant on chromosome 7q36.37 Adjacent to GREM1 on chromosome 15q13.3 is the FMN1 gene, which is transcribed in the reverse orientation (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview). Several groups have described the tissue-specific co-regulation of GREM1 and FMN1, despite their diverse structure and functions.14,36 GREM1 and FMN1 are expressed in similar patterns during kidney organogenesis and both have important functions during renal development.7,36,38 In addition to FMN1, GREM1 also interacts with SLIT1 and SLIT2 in a glycosylation-dependent manner,39 and GREM1 binds to YWHAH in vivo and in vitro.40

In conclusion, GREM1 is implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, and our research has revealed a novel association between the GREM1 gene and diabetic nephropathy. This genetic association was subsequently replicated in a larger collection of individuals with similar case-control phenotypic criteria. We have determined that the T allele of rs1129456 SNP is a significant risk allele for diabetic nephropathy.

Concise Methods

Participants

Ethical approval was obtained from the appropriate research ethics committees and written informed consent was provided by all participants. Genomic DNA was obtained from white participants who were recruited as part of an all-Ireland case-control collection2 specifically designed to investigate genetic risk factors for diabetic nephropathy. Individuals with overt nephropathy (n = 267) had type 1 diabetes at least 10 years before the onset of proteinuria (>0.5 g/24 h) with hypertension (blood pressure >135/85 mmHg and/or treatment with antihypertensive agents) developing on or after the onset of proteinuria. Individuals in the control group (n = 442) had a long duration of diabetes (>15 years), were not prescribed antihypertensive medication, and demonstrated no evidence of microalbuminuria on repeated testing. Type 1 diabetes was diagnosed where age of onset was <35 years and insulin was required from diagnosis. White individuals recruited to the Warren 3 and the Genetics of Kidneys in Diabetes (GoKinD) U.K. collections (cases, n = 597; controls, n = 502) were used as a replicate population.2 Parents of Warren 3 probands (n = 124) were used to assess transmission of alleles to affected offspring.41 The Warren 3/GoKinD U.K. collections were established as a collaborative resource comprising DNA and clinical information from adults having long-duration type 1 diabetes with or without kidney disease and, where possible, their parents. Briefly, all individuals were third generation born in the United Kingdom with similar recruitment criteria to those described for the Irish study, except that type 1 diabetes was diagnosed <31 years of age. Forty-eight control individuals selected for resequencing have been used previously42 and were obtained from the Young Hearts collection.20

Screening

Genomic DNA sequence was characterized from H. sapiens chromosome 15 genomic contig NT_010194.16, gi:37540936. Using AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), 9163 bp were amplified and screened for the variants using WAVE (dHPLC) technology (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE) on 15 case and 15 control individuals. Variants were confirmed by bidirectional capillary sequencing of representative samples on an ABI 3730 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems). Allele frequencies were determined by resequencing in 48 individuals from the Young Hearts collection20 for those SNPs where WAVE mutations suggested a MAF > 5%. Resequencing data were submitted to GenBank43 and unique identifiers were obtained for all variants from dbSNP.44

Selection of SNPs and Genotyping

Haplotype distributions were estimated for all SNPs with a MAF > 10% using snphap.45 Haplotype frequencies were then input to Stata release 8 (http://www.stata.com), and the htsearch command in the htSNP2 package was used to select tag SNPs from among all SNPs for which the MAFs exceeded 10% and genotype distributions were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.46 The htsearch command performs an exhaustive search of all subsets of SNPs to identify the subset of tag SNPs that best represents all SNPs according to the r2 criterion. All SNPs with Pcorrected < 0.05 were selected for further genotyping (Table 3). In silico analysis was performed to assess the putative functionality of proximal genomic variants using Transcription Element Search Software (http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/tess), MatInspector Professional (http://genomatrix.de/cgi-bin/matinspector_prof/mat_fam.pl), UTRScan,21 and miRBase.22 SNPs were genotyped in the Irish case-control collection using MassARRAY iPLEX (Sequenom, San Diego, CA), TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and sequencing technologies.

Statistical Analysis

Genotype frequencies were assessed for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 0.001) using a χ2 goodness-of-fit test. The extent of linkage disequilibrium between pairs of SNPs was evaluated using r2 and visualized in Haploview.47 Genotype distributions in cases and controls were compared using the χ2 test for trend adjusted for the recruitment center, with the level of statistical significance set at 5%. Permutation (n = 100,000 simulations) adjustment for multiple testing was performed in Plink.48 Logistic regression was used to analyze the combined data from the Irish and U.K. collections with a term to represent the collection included in the logistic model.49 This approach enabled recessive, dominant, additive, and general genotypic models to be fitted to the data, and AIC was used where the lowest AIC value identified the best-fitting model. Logistic regression of statistically significant, replicated SNPs was considered with adjustment for potential confounding effects [recruitment center (n = 8), gender, age and duration of diabetes]. The threshold for replication was set at P < 0.05 in a one-sided test to detect an effect observed in the same direction as the original result. Where association was supported by the replicate population, the transmission disequilibrium test was used to investigate transmission of alleles from heterozygous parents to an affected offspring (n = 124).50 The size of the Irish diabetic nephropathy case-control collection provided approximately 90% power to detect an OR of 1.75 for the genotyped htSNPs (MAF > 10%) and >80% power to detect the same OR for the nongenotyped SNPs (MAF > 10% and minimum r2 = 0.73).

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Research and Development Office Northern Ireland, the Health Research Board of Ireland, Science Foundation Ireland, and the Northern Ireland Kidney Research Fund. The Warren 3/U.K. GoKinD Study Group was jointly funded by Diabetes UK and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and includes the following individuals: Professor A.P. Maxwell, Dr. A.J. McKnight, Dr. D.A. Savage (Belfast); Dr. J. Walker (Edinburgh); Dr. S. Thomas, Professor G.C. Viberti (London); Professor A.J.M. Boulton (Manchester); Professor S. Marshall (Newcastle); Professor A.G. Demaine and Dr. B.A. Millward (Plymouth); and Professor S.C. Bain (Swansea).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. McKnight AJ, O'Donoghue D, Maxwell AP: Annotated chromosome maps for renal disease. Hum Mutat 30: 314–320, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKnight AJ, Woodman AM, Parkkonen M, Patterson CC, Savage DA, Forsblom C, Pettigrew KA, Sadlier D, Groop PH, Maxwell AP: Investigation of DNA polymorphisms in SMAD genes for genetic predisposition to diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 52: 844–849, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wanic K, Placha G, Dunn J, Smiles A, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: Exclusion of polymorphisms in carnosinase genes (CNDP1 and CNDP2) as a cause of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: Results of large case-control and follow-up studies. Diabetes 57: 2547–2551, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu DR, Economides AN, Wang X, Eimon PM, Harland RM: The Xenopus dorsalizing factor Gremlin identifies a novel family of secreted proteins that antagonize BMP activities. Mol Cell 1: 673–683, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Capdevila J, Tsukui T, Rodriquez EC, Zappavigna V, Izpisua Belmonte JC: Control of vertebrate limb outgrowth by the proximal factor Meis2 and distal antagonism of BMPs by Gremlin. Mol Cell 4: 839–849, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lappin DW, Hensey C, McMahon R, Godson C, Brady HR: Gremlins, glomeruli and diabetic nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 9: 469–472, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michos O, Panman L, Vintersten K, Beier K, Zeller R, Zuniga A: Gremlin-mediated BMP antagonism induces the epithelial-mesenchymal feedback signaling controlling metanephric kidney and limb organogenesis. Development 131: 3401–3410, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y, Zhang Q: Bone morphogenetic protein-7 and Gremlin: New emerging therapeutic targets for diabetic nephropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 383: 1–3, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Topol LZ, Marx M, Laugier D, Bogdanova NN, Boubnov NV, Clausen PA, Calothy G, Blair DG: Identification of drm, a novel gene whose expression is suppressed in transformed cells and which can inhibit growth of normal but not transformed cells in culture. Mol Cell Biol 17: 4801–4810, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McMahon R, Murphy M, Clarkson M, Taal M, Mackenzie HS, Godson C, Martin F, Brady HR: IHG-2, a mesangial cell gene induced by high glucose, is human gremlin. Regulation by extracellular glucose concentration, cyclic mechanical strain, and transforming growth factor-beta1. J Biol Chem 275: 9901–9904, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murphy M, Godson C, Cannon S, Kato S, Mackenzie HS, Martin F, Brady HR: Suppression subtractive hybridization identifies high glucose levels as a stimulus for expression of connective tissue growth factor and other genes in human mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 274: 5830–5834, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yanagita M: Modulator of bone morphogenetic protein activity in the progression of kidney diseases. Kidney Int 70: 989–993, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dolan V, Murphy M, Sadlier D, Lappin D, Doran P, Godson C, Martin F, O'Meara Y, Schmid H, Henger A, Kretzler M, Droguett A, Mezzano S, Brady HR: Expression of gremlin, a bone morphogenetic protein antagonist, in human diabetic nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 45: 1034–1039, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khokha MK, Hsu D, Brunet LJ, Dionne MS, Harland RM: Gremlin is the BMP antagonist required for maintenance of Shh and Fgf signals during limb patterning. Nat Genet 34: 303–307, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang SN, Lapage J, Hirschberg R: Loss of tubular bone morphogenetic protein-7 in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2392–2399, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roxburgh SA, Kattla JJ, Curran SP, O'Meara YM, Pollock CA, Goldschmeding R, Godson C, Martin F, Brazil DP: Allelic depletion of grem1 attenuates diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 8: 1641–1650, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walsh DW, Roxburgh SA, McGettigan P, Berthier CC, Higgins DG, Kretzler M, Cohen CD, Mezzano S, Brazil DP, Martin F: Co-regulation of Gremlin and Notch signaling in diabetic nephropathy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1782: 10–21, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carvajal G, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Aros C, Ardiles L, Flores C, Carpio D, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J, Mezzano S: Gremlin: A novel mediator of epithelial mesenchymal transition and fibrosis in chronic allograft nephropathy. Transplant Proc 40: 734–739, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mezzano S, Droguett A, Burgos ME, Aros C, Ardiles L, Flores C, Carpio D, Carvajal G, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J: Expression of gremlin, a bone morphogenetic protein antagonist, in glomerular crescents of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1882–1890, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boreham C, Savage JM, Primrose D, Cran G, Strain J: Coronary risk factors in schoolchildren. Arch Dis Child 68: 182–186, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pesole G, Liuni S: Internet resources for the functional analysis of 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Trends Genet 15: 378, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ: miRBase: Tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D154–D158, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stenvinkel P, Karimi M, Johansson S, Axelsson J, Suliman M, Lindholm B, Heimburger O, Barany P, Alvestrand A, Nordfors L, Qureshi AR, Ekstrom TJ, Schalling M: Impact of inflammation on epigenetic DNA methylation—A novel risk factor for cardiovascular disease? J Intern Med 261: 488–499, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M: CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol 196: 261–282, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suzuki M, Shigematsu H, Shames DS, Sunaga N, Takahashi T, Shivapurkar N, Iizasa T, Frenkel EP, Minna JD, Fujisawa T, Gazdar AF: DNA methylation-associated inactivation of TGFbeta-related genes DRM/Gremlin, RUNX3, and HPP1 in human cancers. Br J Cancer 93: 1029–1037, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26. Ezura Y, Sekiya I, Koga H, Muneta T, Noda M: Methylation status of CpG islands in the promoter regions of signature genes during chondrogenesis of human synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Arthritis Rheum 60: 1416–1426, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai EC: Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet 30: 363–364, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mertens PR, Raffetseder U, Rauen T: Notch receptors: A new target in glomerular diseases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 2743–2745, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Niranjan T, Bielesz B, Gruenwald A, Ponda MP, Kopp JB, Thomas DB, Susztak K: The Notch pathway in podocytes plays a role in the development of glomerular disease. Nat Med 14: 290–298, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Topol LZ, Modi WS, Koochekpour S, Blair DG: DRM/GREMLIN (CKTSF1B1) maps to human chromosome 15 and is highly expressed in adult and fetal brain. Cytogenet Cell Genet 89: 79–84, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The International HapMap consortium: A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449: 851–861, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hills T, Todd P: Population heterogeneity and individual differences in an assortative agent-based marriage and divorce model (MADAM) using search with relaxing expectations. JASSS 11: 5, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Covic AM, Iyengar SK, Olson JM, Sehgal AR, Constantiner M, Jedrey C, Kara M, Sabbagh E, Sedor JR, Schelling JR: A family-based strategy to identify genes for diabetic nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 37: 638–647, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thameem F, Puppala S, He X, Arar NH, Stern MP, Blangero J, Duggirala R, Abboud HE: Evaluation of gremlin 1 (GREM1) as a candidate susceptibility gene for albuminuria-related traits in Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 58: 1496–1502, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zuniga A, Michos O, Spitz F, Haramis AP, Panman L, Galli A, Vintersten K, Klasen C, Mansfield W, Kuc S, Duboule D, Dono R, Zeller R: Mouse limb deformity mutations disrupt a global control region within the large regulatory landscape required for Gremlin expression. Genes Dev 18: 1553–1564, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lettice LA, Horikoshi T, Heaney SJ, van Baren MJ, van der Linde HC, Breedveld GJ, Joosse M, Akarsu N, Oostra BA, Endo N, Shibata M, Suzuki M, Takahashi E, Shinka T, Nakahori Y, Ayusawa D, Nakabayashi K, Scherer SW, Heutink P, Hill RE, Noji S: Disruption of a long-range cis-acting regulator for Shh causes preaxial polydactyly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 7548–7553, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wynshaw-Boris A, Ryan G, Deng CX, Chan DC, Jackson-Grusby L, Larson D, Dunmore JH, Leder P: The role of a single formin isoform in the limb and renal phenotypes of limb deformity. Mol Med 3: 372–384, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schneider M, Lane L, Boutet E, Lieberherr D, Tognolli M, Bougueleret L, Bairoch A: The UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot knowledgebase and its Plant Proteome Annotation Program. J Proteomics 72: 567–573, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Namkoong H, Shin SM, Kim HK, Ha SA, Cho GW, Hur SY, Kim TE, Kim JW: The bone morphogenetic protein antagonist gremlin 1 is overexpressed in human cancers and interacts with YWHAH protein. BMC Cancer 6: 74, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McKnight AJ, Maxwell AP, Fogarty DG, Sadlier D. Savage DA and The Warren 3/UK GoKinD Study Group: Genetic analysis of coronary artery disease single nucleotide polymorphisms in diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2473–2476, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McKnight AJ, Maxwell AP, Patterson CC, Brady HR, Savage DA: Association of VEGF-1499C>T polymorphism with diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complicat 21: 242–245, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL: GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D25–D30, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K: dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 308–311, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. SNPHAP: A Program for Estimating Frequencies of Large Haplotypes of SNPs. Available online at http://www-gene.cimr.cam.ac.uk/clayton/software Accessed July 21, 2009

- 46. Johnson GC, Esposito L, Barratt BJ, Smith AN, Heward J, Di Genova G, Ueda H, Cordell HJ, Eaves IA, Dudbridge F, Twells RC, Payne F, Hughes W, Nutland S, Stevens H, Carr P, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, Tuomilehto J, Gough SC, Clayton DG, Todd JA: Haplotype tagging for the identification of common disease genes. Nat Genet 29: 233–237, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21: 263–265, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81: 559–575, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Clayton DG: Population association. In: Handbook of Statistical Genetics, edited by Balding DJ, Bishop M, Canning C. Chichester, United Kingdom, John Wiley & Sons, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ: Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: The insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Am J Hum Genet 52: 506–516, 1993. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.