Abstract

Cilia dysfunction contributes to renal cyst formation in multiple human syndromes including nephronophthisis (NPHP), Meckel-Gruber syndrome (MKS), Joubert syndrome (JBTS), and Bardet-Beidl syndrome (BBS). Although genetically heterogeneous, these diseases share several loci that affect cilia and/or basal body proteins, but the functions and interactions of these gene products are incompletely understood. Here, we report that the ciliated sensory neurons (CSNs) of C. elegans express the putative transmembrane protein MKS-3, which localized to the distal end of their dendrites and to the cilium base but not to the cilium itself. Localization of MKS-3 and other known MKS and NPHP proteins partially overlapped. By analyzing mks-3 mutants, we found that ciliogenesis did not require MKS-3; instead, cilia elongated and cilia-mediated chemoreception was abnormal. Genetic analysis indicated that mks-3 functions in a pathway with other mks genes. Furthermore, mks-1 and mks-3 genetically interacted with a separate pathway (involving nphp-1 and nphp-4) to influence proper positioning, orientation, and formation of cilia. Combined disruption of nphp and mks pathways had cell nonautonomous effects on C. elegans sensilla. Taken together, these data demonstrate the importance of mutational load on the presentation and severity of ciliopathies and expand the understanding of the interactions between ciliopathy genes.

Ciliopathies, or diseases associated with cilia dysfunction, display a diverse array of clinical features. Meckel-Gruber syndrome (MKS) is a severe ciliopathy characterized by renal cystic dysplasia, polydactyly, occipital encephalocele, and perinatal death.1 MKS is an autosomal recessive, genetically heterogeneous disorder with at least six associated loci (MKS1 through MKS6). The five identified MKS genes encode cilia and/or basal body proteins.2–7 Interestingly, mutations in several of the MKS genes have been found in relatively milder ciliopathies such as nephronophthisis (NPHP), Joubert syndrome (JBTS), and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS). For example, some MKS1 mutations manifest BBS- or NPHP-like phenotypes, and mutations in MKS3 were identified as causing JBTS or NPHP.8–11 Such findings suggest that these diseases represent a spectrum of phenotypes resulting from a common underlying etiology.

Studies conducted in both Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Caenorhabditis elegans have provided important insights into cilia biology and have helped identify conserved cilia genes. Homologs of several ciliopathy-associated proteins concentrate at the base of the cilium in C. elegans. Examples include the C. elegans homologs of human nephrocystin-1 (NPHP-1), nephrocystin-4 (NPHP-4), MKS-1 (MKS-1/XBX-7), and multiple BBS proteins.12–14 Analysis of C. elegans nphp-1 and nphp-4 mutants revealed involvement of these genes in cilia-mediated signaling responses such as chemoattraction, male mating behavior, foraging behavior, and lifespan.12,13,15 Although cilia morphology appears overtly normal in nphp-1 and nphp-4 single and double mutants, electron micrographs show occasional microtubule axonemal defects in some cilia.16 Mutations in mks-1 or either of two genes encoding proteins structurally related to MKS-1 (mksr-1/tza-2 and mksr-2/tza-1) caused no discernable defects in cilia morphology.12,17 However, we found that worms with a mutation in mks-1 (or either mksr gene) and either nphp-1 or nphp-4 (e.g., mks-1;nphp-4 double mutants) had severe defects in cilia formation, positioning, and orientation.12 On the basis of these data, we proposed that the mks family of genes (mks-1, mksr-1, and mksr-2) participate in one genetic pathway affecting cilia whereas nphp-1 and nphp-4 participate in a second, separate but at least partially redundant, pathway; disruption of either pathway alone has no overt effect on cilia morphology whereas disruption of both pathways is detrimental to cilia formation and/or maintenance.

Herein, we demonstrate that the transmembrane protein MKS-3 (F35D2.4), the homolog of the human ciliopathy protein MKS-3/tmem67/meckelin, localizes to two distinct domains in C. elegans ciliated sensory neurons (CSNs), one at the distal end of the dendrite (dendritic tip) and the second at the cilium base. Localization at the cilium base overlaps that of MKS-1. Mimicking the elongation of cilia resulting from disruption of MKS-3 in rodents,18,19 C. elegans mks-3 mutants form cilia that are increased in length. Our data indicate a genetic interaction between mutations in mks-3 and nphp-4 that causes cilia and sensilla morphology defects. These phenotypes are not seen in worms with combined mutations affecting mks-3 and any of the other mks-1 gene family members, although cilia function is further impaired in mks-3;mks-1;nphp-4 triple mutants. Intriguingly, our analysis also revealed that mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants exhibit cell nonautonomous defects in the connections between sheath and socket cells, which, along with the CSNs, comprise the C. elegans sensory organs (sensilla). Together, the localization of MKS-3 and genetic interaction data indicate that mks-3 can be functionally assigned to the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2 genetic pathway. More importantly, this report provides further insight into the interplay of the ciliopathy proteins in the influence on cilia function and reflects the role of genetic background in the severity of disease.

Results

mks-3 Encodes a Predicted Seven Transmembrane-Spanning Protein

Recently, tmem67 was identified as the gene responsible for phenotypes in the Wistar polycystic kidney rat, the bilateral polycystic kidney mouse, and also as a disease locus for human MKS and JBTS patients.5,18 MKS3 is a predicted seven transmembrane-spanning protein that colocalizes with acetylated α-tubulin along the cilium axoneme in mammalian inner medullar collecting duct cells.9,20 In vivo and in vitro data implicate roles of MKS3 in ciliogenesis and cilium length control, branching morphogenesis in the kidney, centriole migration and duplication, and endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation.9,19,21 The homolog of MKS3 in C. elegans, F35D2.4 (hereafter referred to as MKS-3), has not been described. BLAST analysis indicates that the nematode mks-3 gene product is 30% identical and 46% similar to the human protein. On the basis of computational analysis, it also contains each of the seven transmembrane domains predicted in human MKS-3, a cysteine-rich region near the N-terminus, and a highly conserved region in the C-terminal tail (Supplementary Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 2).

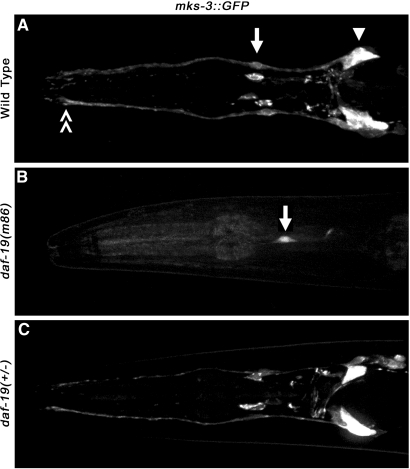

DAF-19 Regulates Expression of mks-3 in CSNs

The C. elegans MKS3 homolog (mks-3) was first identified as a candidate cilia gene in a computational search for X-box promoter elements, which are utilized by the ciliogenic RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19c to drive gene expression in CSNs.22–24 A putative X-box motif was identified in the promoter of mks-3 at position −159 relative to the predicted translational start. We generated an mks-3::GFP reporter comprised of a 320-bp promoter segment and a portion of the first exon fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP). In wild-type worms we observed expression of mks-3::GFP in the amphid and labial neurons in the head (Figure 1A) and phasmid neurons of the tail (data not shown). This confirmed similar mks-3 promoter analyses performed by Efimenko et al.22 mks-3::GFP expression was nearly abolished in homozygous daf-19(m86) mutant background but could be restored by backcrossing with daf-19(+/+) worms (Figure 1, B and C). These data suggest mks-3 is regulated by the DAF-19 transcription factor.

Figure 1.

Expression and DAF-19 regulation of mks-3. (A through C) Confocal fluorescence images of worms coexpressing mks-3::GFP. (A) mks-3::GFP was strongly expressed in amphid (arrowhead) and labial (arrow) sets of neurons of the head, which both extend dendritic processes to the (double arrowhead) anterior of the worm where they project sensory cilia. (B) mks-3 transgene expression was almost completely abolished in worms crossed into daf-19(m86) mutant background. mks-3::GFP was faintly detected only in labial neurons (arrow). (C) Outcrossing transgenic worms from daf-19(m86) to daf-19(+) restored expression of mks-3::GFP.

MKS-3 Concentrates at the Base of the Cilium in C. elegans

Reported colocalization of endogenous mouse MKS3 with acetylated α-tubulin in mammalian inner medullar collecting duct cells indicates that in mammals MKS3 is present along the ciliary axoneme.9 To determine if C. elegans MKS-3 also localizes to the cilium, we generated an MKS-3 translational fusion construct comprised of the 320-bp promoter segment and the entire coding region of mks-3 fused in frame with GFP (MKS-3::GFP). MKS-3::GFP, coexpressed in wild-type worms with a cilium axoneme marker [XBX-1::tdTomato, dynein light intermediate chain involved in retrograde intraflagellar transport (IFT)], localized to the base of cilia, and remarkably was not evident along the cilium axoneme (Figure 2B through 2D, Supplementary Movie 1). MKS-3::GFP was present at its highest levels at the cilium base (Supplementary Figure 3, A and A′, region 3) and was also localized to the dendritic tips of CSNs (Supplementary Figure 3, A and A′, region 1). Because MKS-3 possesses putative transmembrane domains, we compared localization of MKS-3::GFP with a known membrane-associated protein, retinitis pigmentosa 2 (RP2::GFP).25,26 In single confocal sections of phasmid neurons, RP2::GFP and MKS-3:GFP concentrated around the edges of dendritic tips (Figure 3). Membrane association of MKS-3::GFP was not observed in any other regions of the CSN dendrites (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MKS-3 concentrates at the base of cilia in C. elegans. (A) An illustration depicting the anatomical positions of (left) amphid cilia bundles in the head and (right) phasmid cilia bundles in the tail with respect to (middle) a differential interference contrast image of the full body of an adult hermaphrodite worm. Red represents cilia axonemes, green represents bases of cilia, and blue represents the dendritic processes from which the cilia project. Short labial cilia surrounding the distal region of the amphid bundles and the degenerate PQR cilium near the phasmid bundles are not shown. (B through D) Confocal fluorescence images of wild-type transgenic worms coexpressing MKS-3::GFP (driven by its endogenous promoter) and XBX-1/dynein light intermediate chain::tdTomato (driven by the osm-5 promoter). With respect to XBX-1, which freely entered the cilia (arrowheads), MKS-3::GFP concentrated specifically at the base of cilia (arrows) on (B and D, left column) sensory neurons in the head and (C and D, right column) sensory neurons in the tail. (E) Confocal fluorescence images of wild-type transgenic worms coexpressing MKS-3::GFP and MKS-1::tdTomato (driven by its endogenous promoter). With respect to MKS-3::GFP, MKS-1::GFP localized only to the proximal end of cilia where MKS-3::GFP concentrated most intensely (arrows). Scale = 5 μm.

Figure 3.

Localization of MKS-3 in the dendritic tip resembles that of the membrane-associated protein RP2. Single-section confocal fluorescence images of wild-type transgenic worms expressing (A) RP2::GFP (driven by its endogenous promoter) or (B) MKS-3::GFP. One phasmid neuronal ciliated ending is shown in each panel. RP2::GFP accumulated around the edges of the dendritic tip (dt), indicative of membrane association, but was not present at the cilium base (cb). MKS-3::GFP also accumulated around the edges of the dendritic tip in addition to concentrating at the cilium base. Scale = 5 μm.

Because mutations in MKS1 and MKS3 result in similar disease phenotypes in humans, and the two associated proteins are reportedly found in complex in mammalian cells, we compared localization of MKS-3::GFP to MKS-1::tdTomato in C. elegans (Figure 2E, Supplementary Movie 2). MKS-1::tdTomato localization was tightly restricted to the base of the cilium in a domain that overlapped with a portion of MKS-3::GFP (Supplementary Figure 3B). However, MKS-1::tdTomato was not found in adjacent dendritic tips where MKS-3::GFP diffusely localized (Supplementary Figure 3, B and B′, region 1).

Characterization of an mks-3 Deletion Allele

To analyze mks-3 gene function in C. elegans, we obtained a genetic mutant FX2547 mks-3(tm2547) from the National Bioresource Project (Japan). The tm2547 allele contains a large internal genomic deletion of 949 nucleotides. Reverse-transcriptase PCR analysis of the mutant transcript revealed that the deletion fuses exons 4 and 7 and creates a translational frameshift resulting in a premature stop (Supplementary Figure 1B). tm2547 would therefore encode a truncated protein of only 152 amino acids (compared with 897 amino acid full length) lacking all of the transmembrane domains. Thus, tm2547 likely represents a null allele (Supplementary Figure 1, B and C).

mks-3 Is Required for Normal Chemotaxis but Not Ciliogenesis

In C. elegans, direct exposure to the environment via pores in the cuticle allows the membrane of amphid and phasmid cilia in the head and tail of the worm, respectively, to contact and absorb fluorescence hydrophobic dye (DiI). mks-3(tm2547) mutant worms absorbed DiI normally into amphid and phasmid neurons (Figure 4B), indicating that at this level of analysis, cilia are properly formed in this mutant background. This is consistent with the presence of cilia on rodent and human cells with MKS3 mutations.18,19

Figure 4.

mks-3(tm2547) mutants dye-fill normally. The ability to uptake DiI was examined in wild-type worms and mks-3(tm2547) mutants. Confocal fluorescence images of DiI staining are shown. Indicative of properly formed cilia, (left) wild-type and (right) mks-3(tm2547) worms consistently absorbed DiI into CSNs in the head (large panels) and tail (insets). The four phasmid cell bodies are outlined in the insets. Scale = 7 μm.

mks-3(tm2547) mutants were next analyzed for possible cilia-mediated signaling defects including altered chemotactic response to volatile chemical attractants, avoidance of regions of high osmolarity, and foraging behavior in the presence of food. We previously reported that a mutation in mks-1 did not affect any of these behaviors.12 Similarly, we observed no defects in foraging or osmotic avoidance as a result of the mks-3(tm2547) mutation (data not shown). However, mks-3(tm2547) mutants had decreased chemotactic response toward the attractant benzaldehyde (Figure 5). This deficiency was less severe than that observed in retrograde IFT che-11 mutants, in which cilia are severely malformed (Figure 5). Because benzaldehyde sensation occurs specifically through the amphid wing C (AWC) neuron, we examined whether mks-3(tm2547) mutants had cilium morphologic defects in this cell type.27,28 In mks-3(tm2547) mutant worms expressing GFP driven by the AWC-specific str-2 promoter, no alterations of the wing-like structure of the AWC ciliated endings were observed (Supplementary Figure 4). These data indicate that MKS-3 is not necessary for cilia-mediated dye uptake or for AWC wing formation but is required for normal cilia-initiated sensory signaling.

Figure 5.

mks-3 mutants exhibit reduced chemotaxis toward benzaldehyde. Compared with wild type, mks-3(tm2547) and nphp-4(tm925) single mutants were mildly but significantly defective in response to a volatile attractant. Severity of mks-3;mks-1;nphp-4 triple mutant chemotaxis deficiency was similar to retrograde IFT che-11(e1810) mutants, which were used as a negative control. Each group was assayed at least four times with 50 to 120 worms per run. Error bars represent SD. No significant difference was observed in groups represented by bars of matching color. P < 0.05 was deemed significant.

mks-3 Functions as Part of the mks-1 Genetic Pathway

The mks related genes (mks-1, mksr-1, and mksr-2) and the nphp genes (nphp-1/nphp-4) act in two distinct but functionally redundant genetic pathways that are required for proper C. elegans sensilla morphology. Because MKS3 mutations have been identified in MKS and NPHP patients, we assessed whether mks-3 functions as part of either the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2 or nphp-1/nphp-4 genetic pathways.11 For this analysis we first performed chemotaxis assays on mks-3;mks-1 and mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants to determine whether this would exacerbate the mks-3(tm2547) chemotaxis deficiency. Compared with mks-3(tm2547) mutants, in which chemoattraction toward benzaldehyde was reduced, neither addition of the mks-1(tm2705) nor nphp-4(tm925) mutations resulted in alterations of chemotactic response (Figure 5). Combination of the mks-1(tm2705) and nphp-4(tm925) mutations also did not reduce chemotaxis in comparison to nphp-4(tm925) single mutants (Figure 5). However, in mks-3;mks-1;nphp-4 triple mutant animals, chemotaxis was diminished in comparison to any of the single or double mutants and resembled the defect seen in IFT che-11 mutants, indicating a genetic interaction between mks-3, mks-1, and nphp-4 in chemosensory responses.

To further examine the relationship between mks-3 and the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2 and nphp-1/nphp-4 genetic pathways, we analyzed mks-3;mksr-2 and mks-3;nphp-4 mutant strains for potential defects in amphid and phasmid ciliogenesis. Cilia were labeled using a transgene expressing the IFT complex B protein CHE-13::YFP (IFT57).29 We observed no overt cilia morphology defects in mks-3;mksr-2 mutants (Figure 6, A and B). In contrast, severe cilia and dendrite abnormalities were apparent in mks-3;nphp-4 mutants (Figure 6C). As previously seen in mks-1;nphp-4 mutants, defects in mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants included loss of amphid cilia fasciculation in the head and shortened misoriented cilia projecting from malformed phasmid dendrites in the tail (Figure 6C).12 Quantification of phasmid cilia length confirmed that mks-3;nphp-4 mutants had significantly shorter cilia than wild-type worms and mks-3(tm2547) mutants (Table 1). IFT movement was still evident in the shortened cilia of mks-3;nphp-4 mutants (Supplementary Movie 3). As part of this analysis we uncovered that phasmid cilia in mks-3(tm2547) single mutants were consistently longer than wild-type worms (Table 1).

Figure 6.

mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants have short and incorrectly positioned cilia. Cilia morphology was analyzed in confocal fluorescence images of wild-type, mks-3(tm2547), mks-3;mksr-2, and mks-3;nphp-4 worms expressing the transgenic IFT particle B protein CHE-13::YFP. (A and B) Cilia morphology appeared overtly normal in wild-type (top), mks-3(tm2547) (middle), and mks-3;mksr-2 (bottom) strains. Arrowheads, distal ends of cilia; double arrowheads, cilia bases. (A′ and C′) 1.66× magnification of amphid bundles in A and C, respectively. Arrows indicate the shorter labial cilia that are not part of the amphid channel organs. (B) Compared with wild type (top), mutant strains mks-3(tm2547) and mks-3;mksr-2 exhibited no abnormalities in the extension of dendrites (dotted lines) from the phasmid cell bodies (arrows) nor in the projection of full-length cilia (double-headed arrow) from the distal tips of the dendrites. (C) Amphid and (D) phasmid cilia arrangement and morphology was abnormal in mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants. Compared with wild type, some amphid cilia were positioned posterior with the respect to the rest of the sensory organ (C′, arrowhead), and other amphid cilia often altogether lacked axonemes (arrow). (D) Phasmid dendrites often failed to properly extend from the cell bodies and projected stunted cilia. Scale = 5 μm.

Table 1.

Phasmid cilia length measurements

| Strain | Length (μm) ± SEM CHE-13::YFP |

P Value Compared with |

Length (μm) ± SEM TBB-4::GFP |

P Value Compared with |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | mks-3 (tm2547) | Wild Type | mks-3 (tm2547) | mks-3; nphp-4 | |||

| Wild type | 7.06 ± 0.11 | 6.77 ± 0.13 | |||||

| mks-3(tm2547) | 7.42 ± 0.11 | 0.02a | 7.27 ± 0.20 | 0.04a | |||

| mks-3;mksr-2 | 7.23 ± 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.2 | ||||

| mks-3;mks-1 | 7.39 ± 0.17 | 0.007a | 0.64 | ||||

| mks-3;nphp-4 | 3.63 ± 0.19 | <0.0001a | <0.0001a | 4.59 ± 0.29 | <0.0001a | <0.0001a | |

| mks-3;nphp-4 + Ex1 | 5.98 ± 0.29 | 0.002a | |||||

| (MKS-3::tdTomato) | |||||||

aP < 0.05 was deemed significant.

Because overexpression of the IFT protein OSM-6 was observed by others to synthetically inhibit ciliogenesis in nphp-4(tm925) mutants, and because utilization of an IFT protein as a marker for cilia morphology may complicate assessment of cilia morphology, we also analyzed cilia in mks-3 single and compound mutants using the β-tubulin protein TBB-4.16 As observed with CHE-13::YFP, phasmid cilia length measurements based on TBB-4::GFP fluorescence indicated longer cilia in mks-3(tm2547) mutants compared with wild type (Supplementary Figure 4D, Table 1). In contrast, phasmid axonemes were shortened in mks-3;nphp-4 mutants although not in mks-3;mks-1 mutants (Supplementary Figure 4, E and F, Table 1). These data indicate that mks-3(tm2547) and mks-3;nphp-4 mutants have altered cilium morphology reflected at the microtubule level.

Consistent with cilia morphology defects, mks-3;nphp-4 mutants were hindered in the ability to uptake DiI (Figure 7 and Table 2). Although 89.0% of mks-3;nphp-4 mutant amphid neuron bundles dye-filled, intensity of dye-filling was consistently less than wild-type controls. Furthermore, phasmid neurons rarely stained with DiI (Figure 7 and Table 2). In comparison, amphid dye-filling at some level was only observed in 27.6% of mks-3;mks-1;nphp-4 triple mutants. We were able to partially rescue the mks-3;nphp-4 phasmid dye-filling defect by generating mutant worms coexpressing wild-type MKS-3::tdTomato and TBB-4::GFP (Figure 7, Supplementary Figure 4G). Phasmid cilia length, as determined via TBB-4::GFP fluorescence, was also partially restored in rescue animals (Supplementary Figure 4G, Table 1).

Figure 7.

Partial restoration of phasmid dye-filling in mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants by transgene rescue. The ability to uptake DiI was examined in wild-type worms, mks-3(tm2547);nphp-4(tm925) double mutants, and transgenic mks-3(tm2547);nphp-4(tm925) double mutants coexpressing MKS-3::tdTomato and the coelomocyte marker UNC-122::GFP from a nonintegrated extrachromosomal array (Ex1). Phasmid dye-filling was regularly observed in wild-type worms but rarely seen in mks-3(tm2547);nphp-4(tm925) double mutants. Progeny of mks-3(tm2547);nphp-4(tm925) double mutants coexpressing MKS-3::tdTomato and UNC-122::GFP were exposed to DiI and then siblings were segregated as transgenic versus nontransgenic on the basis of the presence or absence of UNC-122::GFP signal, respectively. Partial rescue of phasmid dye-filling was observed in transgenic double mutants compared with nontransgenic siblings. At least 100 worms in each category were analyzed. Error bars represent SEM.

Table 2.

Summary of mks and nphp mutant phenotypes

| Strain | Percent Dye-Fillinga |

Benzaldehyde Chemotaxisa | Cilia Lengtha (Phasmid) | Dendrite Extensiona (Phasmid) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphid | Phasmid | ||||

| Wild type | 100 | 100 | + | + | + |

| mks-1(tm2705) | 100 | 100 | + | + | + |

| mks-3(tm2547) | 100 | 100 | −− | ++ | + |

| mks-3;mks-1 | 100 | 100 | −− | ++ | + |

| nphp-4(tm925) | 100 | 100 | − | + | + |

| mks-1;nphp-4 | 94.3 | 52.7 | − | − | − |

| mks-3;nphp-4 | 89 | 14.3 | −− | − | − |

| mks-3;mks-1;nphp-4 | 27.6 | <1 | −−− | ND | ND |

aData combined from study presented here and reference 12.

+, similar to wild type; ++, greater than wild type; −, slightly defective; −−, moderately defective; −−−, severely defective, similar to IFT mutant; ND, not determined.

In C. elegans, pores through which amphid and phasmid cilia extend consist of a socket cell-derived channel that associates with the cuticle of the worm and a sheath support cell surrounding the cilia bundles, altogether forming the amphid and phasmid sensilla (Figure 8, A and D).30,31 Previously, we observed in mksr-2;nphp-4 mutants in which cilia were short and phasmid dendrites were malformed that sheath cells remain associated as part of the channels despite detachment of the dendrites/cilia from the channels.12 To determine whether this was also true in mks-3;nphp-4 mutants, we generated worms coexpressing XBX-1::tdTomato to visualize dendrite/cilia positioning and f16f9.3::GFP to visualize sheath cells.12 Interestingly, in contrast to results with mksr-2;nphp-4, in mks-3;nphp-4 mutants phasmid sheath cells remained in association with misplaced cilia instead of extending normally to form part of the channels (Figure 8F). No overt sheath cell morphology alterations were observed in the head sensilla of mks-3;nphp-4 mutants, likely because of the presence of properly extended amphid dendrites (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Cell nonautonomous perturbation of phasmid sensilla morphology in mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants. Illustrations of (A) amphid and (D) phasmid sensilla showing attachment of cuticle to socket channels, connections between socket channels and sheath cells (double arrowheads), and connections between sheath cells and dendritic tips (den) (arrowheads). Scale = 1 μm. Modified with permission from Perkins et al.31 (B, C, E, and F) Confocal fluorescence images of worms coexpressing f16f9.3::GFP to mark sheath cells and XBX-1::tdTomato to mark cilia. Compared with (B) wild type, amphid sensory neurons in (C) mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants projected malformed cilia that remained in association with the surrounding sheath cells. Despite apparent detachment from the phasmid channels (dotted lines mark predicted location of channels), phasmid sheath cells remained in association with the misplaced ciliated endings of phasmid neurons (arrowheads) in (F) mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants. (G, H) Confocal fluorescence images of worms coexpressing MAGI-1::GFP to mark socket channels and XBX-1::tdTomato to mark cilia. In (G) wild-type worms, socket cell-expressed MAGI-1::GFP localizes around the distal-most segments of phasmid cilia (arrows), consistent with the location of the socket-derived portion of the phasmid channels. In (H) mks-3;nphp-4 double mutants, socket channels were present. (Left) A pair of short phasmid cilia positioned normally with respect to the socket channel. (Right) Socket channels were most often present (arrow) despite misplacement of cilia, although on rare occasions no socket-expressed MAGI-1::GFP was observed (arrowhead). Scale of all fluorescence images = 5 μm.

To determine whether this apparent detachment of the dendrites and sheath cells from the phasmid channels also affected the sockets, we generated worms coexpressing XBX-1::tdTomato to visualize cilia/dendrite positioning and endogenous promoter-driven MAGI-1::GFP (membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted), which we have found localizes around the channel portion of phasmid sockets (Figure 8G).32 Compared with misplaced phasmid cilia in mks-3;nphp-4 mutants, socket channels remained in association with the cuticle where cilia would normally extend into the external environment (Figure 8, G and H). Together, these data indicate that combined loss of mks-3 and nphp-4 in CSNs results in cell nonautonomous alterations of phasmid sensilla architecture.

Overall, the genetic interactions between mks-3 and nphp-4 with regards to cilia assembly are identical to that obtained when we conducted similar analysis of mks-1 and nphp-4 (Table 2).12 mks-3;nphp-1 mutants were not generated because the genes are closely linked in the genome. Together, our data indicate that mks-3 functions as an additional member of the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2 genetic pathway influencing cilia orientation, cilia positioning, and ciliogenesis in conjunction with the nphp-1/nphp-4 pathway.

Discussion

Although the number of identified cystic kidney disease genes has rapidly increased, our basic understanding of their interconnected functions has lagged. This is an important issue because in human ciliopathies, heterozygous mutations in one disease-related gene can enhance the severity of phenotypes caused by a separate homozygous mutation in another ciliopathy gene in the same individual.10 Additionally, morpholino knockdown of multiple cilia-related disease genes in zebrafish can have synergistic effects on developmental phenotypes.10 These complex interactions between ciliopathy genes are also observed in C. elegans. Combination of an mks-1 mutation with either an nphp-1 or nphp-4 mutation caused ciliogenesis defects not evident in any of the single mutants.12 These observations suggest that genetic background will have a major influence on the severity of cilia-associated phenotypes and indicate that studies in C. elegans will be useful in elucidating the molecular basis of these phenotypes.

In human patients and in rodent models, genetic mutations affecting MKS3 did not inhibit ciliogenesis. Rather, disruption of MKS3 was found to cause centrosome duplication and multiciliation as well as cilia elongation, the latter of which we also found here in C. elegans mks-3 mutants.18,19 This observation is not without precedent, because Nphp3pcy/ko, jck (Nphp9/Nek8), and Bbs4 mutant mice have elongated renal epithelial cilia as well as cystic kidneys.33–35 Additionally, elongation of male-specific CEM cilia in nphp-1 and nphp-4 mutant C. elegans is sometimes observed.16

Not until we combined the mks-3(tm2547) mutation with the nphp-4(tm925) mutation did obvious ciliogenesis defects arise. Because of this genetic interaction and our observation that ciliogenesis was not impaired when the mks-3(tm2547) mutation was combined with mutations in any of the three mks-1 family of genes, we conclude that mks-3 is likely an additional member of the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2 genetic pathway, functioning redundantly with the nphp-1/nphp-4 pathway for proper C. elegans ciliogenesis and sensilla assembly (Supplementary Figure 6). Our finding that the combination of mks-3 and nphp-4 mutations did not additively impair chemotactic response beyond the defect observed in mks-3 single mutants would suggest that mks-3 functions upstream of nphp-4 in a chemosensation pathway. However, the interpretation of this result is complicated by the relatively mild nphp-4 mutant chemotaxis phenotype and the SD observed in the mks-3 and mks-3;nphp-4 mutants. Functional differences between mks-3 and mks-1 within the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2/mks-3 genetic pathway were highlighted by our finding that combination of the mks-1 and mks-3 mutations together with the nphp-4 mutation resulted in further impairment of chemotaxis and ciliogenesis beyond that observed in mks-1;nphp-4 and mks-3;nphp-4 mutants (Supplementary Figure 6). This observation suggests that mks-1 and mks-3 contributions to the mks-1/mksr-1/mksr-2/mks-3 pathway are similar but not identical, which could be reflective of how MKS-3 patients have some clear phenotypic differences from MKS-1 patients.36

The mechanisms by which these genes and pathways influence cilia morphogenesis are not entirely clear. Ultrastructural data indicate that the nphp-1/nphp-4 pathway may be responsible for maintaining the integrity of the ciliary axoneme on the basis of observations of axonemal microtubule defects in these mutants.16 Ultrastructural analysis of mks-1 gene family mutants uncovered no microtubule defects in C. elegans cilia, indicating this pathway may influence cilia morphology in a separate manner from the nphp-1/nphp-4 pathway.17 Because MKS-3 is a transmembrane protein that concentrates at the cilium base, we speculate a partial role of the mks-1/mks-3 genetic pathway in the biology of the cilium membrane, as opposed to the axoneme. Potential functions of the MKS proteins at the cilium base could include processes such as tethering of transition fibers to the membrane/basal body anchoring, regulating the ciliary entry and/or exit of other proteins, or mediating vesicular trafficking of proteins at the cilium base. Thus, the combination of microtubule defects conferred by disruption of the nphp-1/nphp-4 pathway coupled with some form of cilium membrane dysregulation conferred by disruption of the mks-1/mks-3 pathway would together be incompatible with sustaining cilium and sensillum integrity.

Our data indicate that disruption of mks-3 and nphp-4 in C. elegans can cause changes in the morphology of cells in which these genes are not expressed. It has recently been shown that a secreted tectorin-like protein matrix anchors CSN dendritic tips at the initiation point of cell body migration during sensillum development.37 We can envision a role for membrane-bound proteins such as MKS-3 in mediating interactions between the membrane of CSNs and the surrounding matrix and/or sheath/socket cells to help maintain dendritic tip anchoring. Although difficult to predict how MKS-3 could function in membrane interactions in the context of a renal epithelial cell, it should be noted that most primary cilia are located in pockets or depressions in the cell membrane. These pockets are sites of active vesicular transport, thus it would be interesting to evaluate whether MKS-3 in mammalian cells may have an analogous role and mediate the interaction between the membrane of the cilium and the cell membrane.

How specific proteins are shuttled into and out of the ciliary compartment has become a very active area of research because of a current paucity of data and the direct relevance to disease. It is interesting to note that the BBsome, a complex of several BBS proteins, is involved in establishing and regulating the cilium membrane and has been implicated in the trafficking of cilia-specific receptors.38,39 However, the clinical features of BBS are relatively mild when compared with those observed in MKS. It is enticing to speculate that perhaps in MKS the cilium membrane is more fundamentally altered such that most, if not all, roles for cilium-associated signaling are eroded, thus leading to the extreme clinical features observed in this syndrome.

Elucidating the function of genes associated with cystic kidney disease is essential to the understanding of renal and extrarenal pathologies arising in ciliopathy patients. This should include analysis of complex genetic interactions between cilio-cystic genes and the determination of how genetic modifiers can influence disease severity. Herein, we uncovered a role of mks-3 in mediating a subset of cilia signaling activities and demonstrated a redundant requirement of mks-3 and nphp-4 in ciliogenesis and C. elegans sensilla morphology. These analyses demonstrate the utility of the C. elegans system for exploration of the complex genetic interactions between the NPHP, MKS, and other ciliopathy genes and how these interactions may affect disease pathogenesis and presentation in human ciliopathy patients. Understanding how the MKS and NPHP proteins function in cilia formation and/or signaling will provide insight into why their disruption results in systemic developmental abnormalities in higher organisms.

Concise Methods

General Molecular Biology Methods

Molecular biology procedures were performed according to standard protocols.40 C. elegans genomic DNA, C. elegans cDNA, or cloned C. elegans DNA was used for PCR amplifications, for direct sequencing, or for subcloning.40 All PCR for cloning was performed with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland). Clones, primer sequences, and PCR conditions are available upon request. DNA sequencing was performed at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Genomics Core Facility of the Heflin Center for Human Genetics.

DNA and Protein Sequence Analysis

Genome sequence was obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Gene and protein sequences were identified using the database Wormbase and references therein (http://www.wormbase.org). Searches to identify homologs in human, mouse, and Strongylocentrtus purpuratus were performed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST service (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). Protein sequence analyses were performed using Phobius (http://phobius.cbr.su.se).

Strains

Worm strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, C. elegans Knock-out Consortium, and National BioResource Project in Japan. Strains were grown using standard growth methods at 22°C unless otherwise stated.41 The wild-type strain was N2 Bristol. The following mutations were used: JT6924 daf-19(m86)II;daf-12(sa204)X, FX2705 mks-1(tm2705)III, FX2452 mksr-2/tza-1(tm2452)IV, FX925 nphp-4(tm925)V, JT204 daf-12(sa204)X, FX2547 mks-3(tm2547)II, YH499 mks-3(tm2547)II;mks-1(tm2705)III, YH576 mks-3(tm2547)II;nphp-4(tm925)V, YH582 mks-3(tm2547)II;mksr-2/tza-1(tm2452)IV, and YH850 mks-3(tm2547)II;mks-1(tm2705)III;nphp-4(tm925)V. FX2705, FX2547, FX2452, and FX925 were outcrossed at least three times and genotyped by PCR before analysis.

Generation of Constructs and Strains

Vectors for generating transcriptional and translational fusion constructs were modified from pPD95.81 (a gift from A. Fire). pCJF37 (CHE-13::YFP) was generated as described previously.13 pPD95.81::tdTomato was generously provided by M. Barr (Rutgers University). pCP41 (Pf16f9.3::GFP) was generously provided by S. Shaham (The Rockefeller University). pA597 (MAGI-1::GFP) was generously provided by A. Stetak (University of Basel, Switzerland).32 Pstr-2::GFP construct was generously provided by C. Bargmann (The Rockefeller University). cGV1 (pPD95.81::Gateway::GFP) and cGV6 were generated by blunt cloning the Gateway cassette c.1 into the SmaI site of pPD95.81 and pPD95.81::tdTomato, respectively (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). cGV7.1 (Posm-5::Gateway::GFP) was generated by transferring the 250-bp promoter of osm-5 from pCJF3 to cGV1 at HindIII/SphI sites. p329.1 (mks-3::GFP) was generated by inserting pPD95.81 with a 300-bp promoter fragment amplified from N2 genomic DNA corresponding to the region immediately upstream and one codon downstream of the mks-3 ATG. p330.1 (MKS-3::GFP) and p367.1 (MKS-3::tdTomato) were generated by amplifying the 300-bp promoter and entire coding region of mks-3 from N2 genomic DNA and inserting the fragment into cGV1 or cGV6, respectively, via Gateway technology. p341 (RP2::GFP) was generated by amplifying the 1.0-kb promoter and entire coding region of k08d12.2 from N2 genomic DNA and inserting the fragment in cGV7.1 via Gateway technology. p344 (NPHP1::tdTomato) was generated by amplifying the 300-bp promoter and entire coding region of nphp-1 from N2 genomic DNA and inserting the fragment in cGV6 via Gateway technology. p346.1 (MKSR-1::tdTomato) was generated by amplifying the 1.7-kb promoter and entire coding region of mksr-1 from N2 genomic DNA and inserting the fragment in cGV6 via Gateway technology. p368 (Posm-5::TBB-4::GFP) was generated by amplifying the entire coding region of tbb-4 from N2 genomic DNA and inserting the fragment in cGV7.1 via Gateway technology. p327.1 (MKS-1::tdTomato) was generated by subcloning the 3.2 kb mks-1 genomic fragment from p318 to pPD95.81::tdTomato.12 p328.1 (Posm-5::XBX-1::tdTomato) was generated by subcloning the 700-bp tdTomato fragment from pPD95.81 to pCJF17.1 (Posm-5::XBX-1::YFP).42 Transgenic worms were generated as described previously.43 A total of 56 independent extrachromosomal arrays containing MKS-3::GFP or MKS-3::tdTomato were generated, 55 of which expressed MKS-3 in the pattern reported here. A single array appeared to greatly overexpress MKS-3::tdTomato, resulting in extensive aggregation of the fusion protein in dendritc tips (data not shown).

Imaging

Worms were anesthetized using 10 mM Levamisole and immobilized on 2% agar pads for imaging. Confocal analysis was performed on a Nikon 2000U inverted microscope (Melville, KY) outfitted with a PerkinElmer UltraVIEW ERS 6FE-US spinning disk laser apparatus (Shelton, CT). Confocal images were processed with Volocity 5 (Improvision Inc., Waltham, MA). Image processing was performed using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA).

DAF-19 Regulation

To asses DAF-19 regulation in vivo, the transgenic line YH588 was generated by injection of mks-3::GFP into N2. This was then crossed to JT204 and subsequently to JT6924 to achieve daf-19(m86) background. The strain contained a mutation in daf-12(sa204)X to suppress the Daf-c phenotype of daf-19(m86)II. A backcross with JT204 was then used to assess mks-3::GFP expression in daf-19(±) background.

Reverse-Transcriptase PCR

RNA was isolated as described previously from mks-3(tm2547) mutants.29 Complementary DNA was generated using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the manufacturer's instructions. Fragments spanning the deleted region of each respective gene were amplified by PCR and sequenced.

Assays

Dye-filling using DiI (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) was performed as described previously.44 Chemotaxis assays to volatile attractants (benzaldehyde) were performed as described previously.45 Briefly, 10-cm chemotaxis plates containing 2% Difco agar Noble, 5 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgSO4 were poured 12 to 24 hours before experiments. Plates were marked at the center and at opposite sides, 0.5 cm from the edge. A zone was drawn at each side 1.5 cm from each of these spots representing the chemoattractant zone and the control zone. To the spots in each zone 0.2 μl of 1 M sodium azide was added as an anesthetic. In the chemoattractant zone, 1 μl of chemoattractant (diluted 1:100 in 95% ethanol) was added, and at the opposite control zone 1 μl of 95% ethanol alone was added immediately before assays. Worms were grown at room temperature until young adult stage and then were washed three times with M9 medium (0.3% KH2PO4, 0.6% Na2HPO4, 0.5% NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4) and once with sterile deionized water to remove residual bacteria and salts. Fifty to 150 worms were deposited in the drop of water in the center of the plate and were counted at chemoattractant and control zones after 60 minutes. The efficiency of chemotaxis was calculated as the chemotaxis index: the number of worms at the chemoattractant zone minus the number of worms at the control zone divided by the total number of worms on the plate.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Croyle, V. Roper, and E. Brown for technical assistance and N. Berbari and A. O'Connor for review and comments of the manuscript. The C. elegans Genome Sequencing Consortium provided sequence information, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health, provided some of the C. elegans strains used in this study. We thank the National BioResource Project in Japan for the mks-3(tm2547) deletion mutants. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK065655 and R01 DK62758 to B.K.Y. and T32 DK007545-22 to D.J.B.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Synergistic Interaction between Ciliary Genes Reflects the Importance of Mutational Load in Ciliopathies,” on pages 724–726.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexiev BA, Lin X, Sun C. C., Brenner DS: Meckel-Gruber syndrome: Pathologic Manifestations, Minimal diagnostic criteria, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 130: 1236–1238, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baala L, Audollent S, Martinovic J, Ozilou C, Babron MC, Sivanandamoorthy S, Saunier S, Salomon R, Gonzales M, Rattenberry E, Esculpavit C, Toutain A, Moraine C, Parent P, Marcorelles P, Dauge MC, Roume J, Le Merrer M, Meiner V, Meir K, Menez F, Beaufrere AM, Francannet C, Tantau J, Sinico M, Dumez Y, MacDonald F, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Gubler MC, Genin E, Johnson CA, Vekemans M, Encha-Razavi F., Attie-Bitach T.: Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 81: 170–179, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delous M, Baala L, Salomon R, Laclef C, Vierkotten J, Tory K, Golzio C, Lacoste T, Besse L, Ozilou C, Moutkine I, Hellman NE, Anselme I, Silbermann F, Vesque C, Gerhardt C, Rattenberry E, Wolf MT, Gubler MC, Martinovic J, Encha-Razavi F, Boddaert N, Gonzales M, Macher MA, Nivet H, Champion G, Bertheleme JP, Niaudet P, McDonald F, Hildebrandt F, Johnson CA, Vekemans M, Antignac C, Ruther U, Schneider-Maunoury S, Attie-Bitach T, Saunier S: The ciliary gene RPGRIP1L is mutated in cerebello-oculo-renal syndrome (Joubert syndrome type B) and Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet 39: 875–881, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roume J, Genin E, Cormier-Daire V, Ma HW, Mehaye B, Attie T, Razavi-Encha F, Fallet-Bianco C, Buenerd A, Clerget-Darpoux F, Munnich A, Le Merrer M: A gene for Meckel syndrome maps to chromosome 11q13. Am J Hum Genet 63: 1095–1101, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith UM, Consugar M, Tee LJ, McKee BM, Maina EN, Whelan S, Morgan NV, Goranson E, Gissen P, Lilliquist S, Aligianis IA, Ward CJ, Pasha S, Punyashthiti R, Malik Sharif S, Batman PA, Bennett CP, Woods CG, McKeown C, Bucourt M, Miller CA, Cox P, Algazali L, Trembath RC, Torres VE, Attie-Bitach T, Kelly DA, Maher ER, Gattone V H, II, Harris PC, Johnson CA: The transmembrane protein meckelin (MKS3) is mutated in Meckel-Gruber syndrome and the wpk rat. Nat Genet 38: 191–196, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tallila J, Jakkula E, Peltonen L, Salonen R: Kestila M: Identification of CC2D2A as a Meckel syndrome gene adds an important piece to the ciliopathy puzzle. Am J Hum Genet 82: 1361–1367, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kyttala M, Tallila J, Salonen R, Kopra O, Kohlschmidt N, Paavola-Sakki P, Peltonen L, Kestila M: MKS1, encoding a component of the flagellar apparatus basal body proteome, is mutated in Meckel syndrome. Nat Genet 38: 155–157, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Badano JL, Leitch CC, Ansley SJ, May-Simera H, Lawson S, Lewis RA, Beales PL, Dietz HC, Fisher S, Katsanis N: Dissection of epistasis in oligogenic Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nature 439: 326–330, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dawe HR, Smith UM, Cullinane AR, Gerrelli D, Cox P, Badano JL, Blair-Reid S, Sriram N, Katsanis N, Attie-Bitach T, Afford SC, Copp AJ, Kelly DA, Gull K, Johnson CA: The Meckel-Gruber syndrome proteins MKS1 and meckelin interact and are required for primary cilium formation. Hum Mol Genet 16: 173–186, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leitch CC, Zaghloul NA, Davis EE, Stoetzel C, Diaz-Font A, Rix S, Alfadhel M, Lewis RA, Eyaid W, Banin E, Dollfus H, Beales PL, Badano JL, Katsanis N: Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat Genet 40: 443–448, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Otto EA, Tory K, Attanasio M, Zhou W, Chaki M, Paruchuri Y, Wise EL, Wolf MT, Utsch B, Becker C, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Nayir A, Saunier S, Antignac C, Hildebrandt F: Hypomorphic mutations in meckelin (MKS3/TMEM67) cause nephronophthisis with liver fibrosis (NPHP11). J Med Genet 46: 663–670, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams CL, Winkelbauer ME, Schafer JC, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK: Functional redundancy of the B9 proteins and nephrocystins in Caenorhabditis elegans ciliogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2154–2168, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winkelbauer ME, Schafer JC, Haycraft CJ, Swoboda P, Yoder BK: The C. elegans homologs of nephrocystin-1 and nephrocystin-4 are cilia transition zone proteins involved in chemosensory perception. J Cell Sci 118: 5575–5587, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blacque OE, Leroux MR: Bardet-Biedl syndrome: An emerging pathomechanism of intracellular transport. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 2145–2161, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jauregui AR, Barr MM: Functional characterization of the C. elegans nephrocystins NPHP-1 and NPHP-4 and their role in cilia and male sensory behaviors. Exp Cell Res 305: 333–342, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jauregui AR, Nguyen KC, Hall DH, Barr MM: The Caenorhabditis elegans nephrocystins act as global modifiers of cilium structure. J Cell Biol 180: 973–988, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bialas NJ, Inglis PN, Li C, Robinson JF, Parker JD, Healey MP, Davis EE, Inglis CD, Toivonen T, Cottell DC, Blacque OE, Quarmby LM, Katsanis N, Leroux MR: Functional interactions between the ciliopathy-associated Meckel syndrome 1 (MKS1) protein and two novel MKS1-related (MKSR) proteins. J Cell Sci 122: 611–624, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cook SA, Collin GB, Bronson RT, Naggert JK, Liu DP, Akeson EC, Davisson MT: A mouse model for Meckel syndrome type 3. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 753–764, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tammachote R, Hommerding CJ, Sinders RM, Miller CA, Czarnecki PG, Leightner AC, Salisbury JL, Ward CJ, Torres VE, Gattone VH, II, Harris PC: Ciliary and centrosomal defects associated with mutation and depletion of the Meckel syndrome genes MKS1 and MKS3. Hum Mol Genet 18: 3311–3323, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adams M, Smith UM, Logan CV, Johnson CA: Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies. J Med Genet 45: 257–267, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang M, Bridges J, Na CL, Xu Y, Weaver TE: The Meckel-Gruber syndrome protein MKS3 is required for ER-associated degradation of surfactant protein C. J Biol Chem 284: 33377–33383, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Efimenko E, Bubb K, Mak HY, Holzman T, Leroux MR, Ruvkun G, Thomas JH: Swoboda P: Analysis of XBX genes in C. elegans. Development 132: 1923–1934, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swoboda P, Adler HT, Thomas JH: The RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19 regulates sensory neuron cilium formation in C. elegans. Mol Cell 5: 411–421, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Senti G, Swoboda P: Distinct isoforms of the RFX transcription factor DAF-19 regulate ciliogenesis and maintenance of synaptic activity. Mol Biol Cell 19: 5517–5528, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blacque OE, Perens EA, Boroevich KA, Inglis PN, Li C, Warner A, Khattra J, Holt RA, Ou G, Mah AK, McKay SJ, Huang P, Swoboda P, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Baillie DL, Moerman DG, Shaham S, Leroux MR: Functional genomics of the cilium, a sensory organelle. Curr Biol 15: 935–941, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapple JP, Hardcastle AJ, Grayson C, Spackman LA, Willison KR, Cheetham ME: Mutations in the N-terminus of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa protein RP2 interfere with the normal targeting of the protein to the plasma membrane. Hum Mol Genet 9: 1919–1926, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bargmann CI, Hartwieg E, Horvitz HR: Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell 74: 515–527, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Troemel ER, Sagasti A., Bargmann CI: Lateral signaling mediated by axon contact and calcium entry regulates asymmetric odorant receptor expression in C. elegans. Cell 99: 387–398, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haycraft CJ, Schafer JC, Zhang Q, Taulman PD, Yoder BK: Identification of CHE-13, a novel intraflagellar transport protein required for cilia formation. Exp Cell Res 284: 251–263, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ward S, Thomson N, White JG, Brenner S: Electron microscopical reconstruction of the anterior sensory anatomy of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol 160: 313–337, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perkins LA, Hedgecock EM, Thomson JN, Culotti JG: Mutant sensory cilia in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 117: 456–487, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stetak A, Horndli F, Maricq AV, van den Heuvel S, Hajnal A: Neuron-specific regulation of associative learning and memory by MAGI-1 in C. elegans. PLoS One 4: e6019, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bergmann C, Fliegauf M, Bruchle NO, Frank V, Olbrich H, Kirschner J, Schermer B, Schmedding I, Kispert A, Kranzlin B, Nurnberg G, Becker C, Grimm T, Girschick G, Lynch SA, Kelehan P, Senderek J, Neuhaus TJ, Stallmach T, Zentgraf H, Nurnberg P, Gretz N, Lo C, Lienkamp S, Schafer T, Walz G, Benzing T, Zerres K, Omran H: Loss of nephrocystin-3 function can cause embryonic lethality, Meckel-Gruber-like syndrome, situs inversus, and renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet 82: 959–970, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith LA, Bukanov NO, Husson H, Russo RJ, Barry TC, Taylor AL, Beier DR, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O: Development of polycystic kidney disease in juvenile cystic kidney mice: Insights into pathogenesis, ciliary abnormalities, and common features with human disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2821–2831, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mokrzan EM, Lewis JS, Mykytyn K: Differences in renal tubule primary cilia length in a mouse model of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nephron Exp Nephrol 106: e88–e96, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Consugar MB, Kubly VJ, Lager DJ, Hommerding CJ, Wong WC, Bakker E, Gattone VH, II, Torres VE, Breuning MH, Harris PC: Molecular diagnostics of Meckel-Gruber syndrome highlights phenotypic differences between MKS1 and MKS3. Hum Genet 121: 591–599, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heiman MG, Shaham S: DEX-1 and DYF-7 establish sensory dendrite length by anchoring dendritic tips during cell migration. Cell 137: 344–355, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peranen J, Merdes A, Slusarski DC, Scheller RH, Bazan JF, Sheffield VC, Jackson PK: A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell 129: 1201–1213, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berbari NF, Lewis JS, Bishop GA, Askwith CC, Mykytyn K: Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins are required for the localization of G protein-coupled receptors to primary cilia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 4242–4246, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd edition, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brenner S: The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schafer JC, Haycraft CJ, Thomas JH, Yoder BK, Swoboda P: XBX-1 encodes a dynein light intermediate chain required for retrograde intraflagellar transport and cilia assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 14: 2057–2070, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V: Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J 10: 3959–3970, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Starich TA, Herman RK, Kari CK, Yeh WH, Schackwitz WS, Schuyler MW, Collet J, Thomas JH, Riddle DL: Mutations affecting the chemosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139: 171–188, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blacque OE, Reardon MJ, Li C, McCarthy J, Mahjoub MR, Ansley SJ, Badano JL, Mah AK, Beales PL, Davidson WS, Johnsen RC, Audeh M, Plasterk RH, Baillie DL, Katsanis N, Quarmby LM, Wicks SR, Leroux MR: Loss of C. elegans BBS-7 and BBS-8 protein function results in cilia defects and compromised intraflagellar transport. Genes Dev 18: 1630–1642, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]