Abstract

In recent years, the spectral analysis of appropriately defined kernel matrices has emerged as a principled way to extract the low-dimensional structure often prevalent in high-dimensional data. Here, we provide an introduction to spectral methods for linear and nonlinear dimension reduction, emphasizing ways to overcome the computational limitations currently faced by practitioners with massive datasets. In particular, a data subsampling or landmark selection process is often employed to construct a kernel based on partial information, followed by an approximate spectral analysis termed the Nyström extension. We provide a quantitative framework to analyse this procedure, and use it to demonstrate algorithmic performance bounds on a range of practical approaches designed to optimize the landmark selection process. We compare the practical implications of these bounds by way of real-world examples drawn from the field of computer vision, whereby low-dimensional manifold structure is shown to emerge from high-dimensional video data streams.

Keywords: dimension reduction, kernel methods, low-rank approximation, machine learning, Nyström extension

1. Introduction

In recent years, dramatic increases in the available computational power and data storage capabilities have spurred a renewed interest in dimension-reduction methods. This trend is illustrated by the development over the past decade of several new algorithms designed to treat nonlinear structure in data, such as isomap (Tenenbaum et al. 2000), spectral clustering (21, Shi & Malik 2000), Laplacian eigenmaps (Belkin & Niyogi 2003), Hessian eigenmaps (Donoho & Grimes 2003) and diffusion maps (Coifman et al. 2005). Despite their different origins, each of these algorithms requires computation of the principal eigenvectors and eigenvalues of a positive semidefinite kernel matrix.

In fact, spectral methods and their brethren have long held a central place in statistical data analysis. The spectral decomposition of a positive semidefinite kernel matrix underlies a variety of classical approaches such as principal components analysis (PCA), in which a low-dimensional subspace that explains most of the variance in the data is sought, Fisher discriminant analysis, which aims to determine a separating hyperplane for data classification, and multi-dimensional scaling, used to realize metric embeddings of the data.

As a result of their reliance on the exact eigendecomposition of an appropriate kernel matrix, the computational complexity of these methods scales in turn as the cube of either the dataset dimensionality or cardinality (1, Belabbas & Wolfe 2009). Accordingly, if we write  for the requisite complexity of an exact eigendecomposition, large and/or high-dimensional datasets can pose severe computational problems for both classical and modern methods alike. One alternative is to construct a kernel based on partial information; that is, to analyse directly a set of ‘landmark’ dimensions or examples that have been selected from the dataset as a kind of summary statistic. Landmark selection thus reduces the overall computational burden by enabling practitioners to apply the aforementioned algorithms directly to a subset of their original data—one consisting solely of the chosen landmarks—and subsequently to extrapolate their results at a computational cost of

for the requisite complexity of an exact eigendecomposition, large and/or high-dimensional datasets can pose severe computational problems for both classical and modern methods alike. One alternative is to construct a kernel based on partial information; that is, to analyse directly a set of ‘landmark’ dimensions or examples that have been selected from the dataset as a kind of summary statistic. Landmark selection thus reduces the overall computational burden by enabling practitioners to apply the aforementioned algorithms directly to a subset of their original data—one consisting solely of the chosen landmarks—and subsequently to extrapolate their results at a computational cost of  .

.

While practitioners often select landmarks simply by sampling from their data uniformly at random, we show in this article how one may improve upon this approach in a data-adaptive manner, at only a slightly higher computational cost. We begin with a review of linear and nonlinear dimension-reduction methods in §2, and formally introduce the optimal landmark selection problem in §3. We then provide an analysis framework for landmark selection in §4, which in turn yields a clear set of trade-offs between computational complexity and quality of approximation. Finally, we conclude in §5 with a case study demonstrating applications to the field of computer vision.

2. Linear and nonlinear dimension reduction

(a). Linear case: principal components analysis

Dimension reduction has been an important part of the statistical landscape since the inception of the field. Indeed, though PCA was introduced more than a century ago, it still enjoys wide use among practitioners as a canonical method of data analysis. In recent years, however, the lessening costs of both computation and data storage have begun to alter the research landscape in the area of dimension reduction: massive datasets have gone from being rare cases to everyday burdens, with nonlinear relationships among entries becoming ever more common.

Faced with this new landscape, computational considerations have become a necessary part of statisticians’ thinking, and new approaches and methods are required to treat the unique problems posed by modern datasets. Let us start by introducing some notation and explaining the principal (!) issues by way of a simple illustrative example. Assume we are given a collection of N data samples, denoted by the set  , with each sample xi comprising n measurements. For example, the samples xi could contain hourly measurements of the temperature, humidity level and wind speed at a particular location over a period of a day; in this case,

, with each sample xi comprising n measurements. For example, the samples xi could contain hourly measurements of the temperature, humidity level and wind speed at a particular location over a period of a day; in this case,  would contain 24 three-dimensional vectors.

would contain 24 three-dimensional vectors.

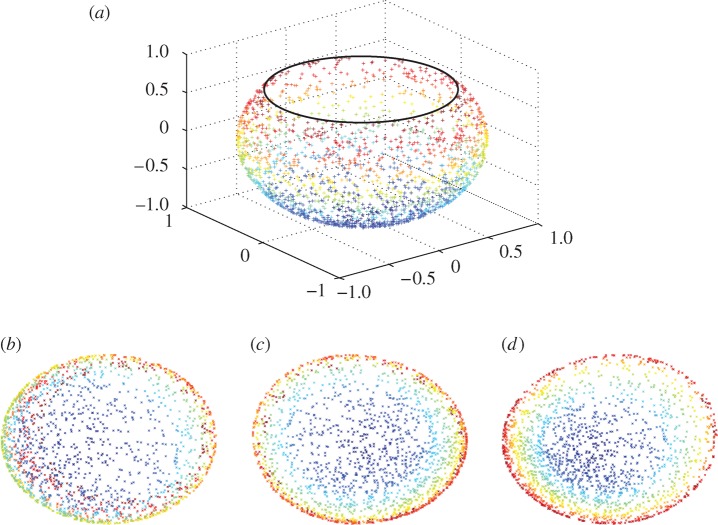

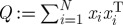

The objective of PCA is to reduce the dimension of a given dataset by exploiting linear correlations among its entries. Intuitively, it is not hard to imagine that, say, as the temperature increases, wind speed might decrease—and thus retaining only the humidity levels and a linear combination of the temperature and wind speed would be, up to a small error, as informative as knowing all three values exactly. By way of an example, consider gathering centred measurements (i.e. with the mean subtracted) into a matrix X, with one measurement per column; for the example above, X is of dimension 3×24. The method of principal components then consists of analysing the positive semidefinite kernel Q=XXT of outer products between all samples xi by way of its eigendecomposition Q=UΛUT, where U:UTU=I is an orthogonal matrix whose columns comprise the eigenvectors of Q, and Λ is a diagonal matrix containing its real, non-negative eigenvalues. The eigenvectors associated with the largest eigenvalues of Q yield a new set of variables according to Y =UTX, which in turn provide the (linear) directions of greatest variability of the data (figure 1).

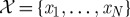

Figure 1.

PCA, with measurements in (a) expressed in (b) in terms of the two-dimensional subspace that best explains their variability. (a) An example set of centred measurements, with projections onto each coordinate axis also shown. (b) PCA yields a plane indicating the directions of greatest variability of the data.

(b). Nonlinear case: diffusion maps and Laplacian eigenmaps

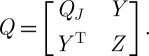

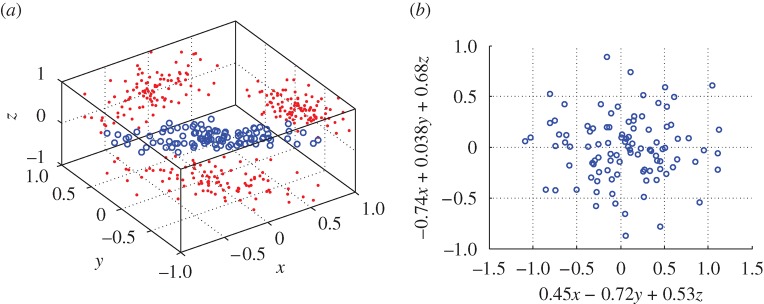

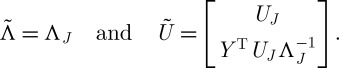

In the above example, PCA will be successful if the relationship between wind speed and temperature (for example) is linear. Nonlinear dimension reduction refers to the case in which the relationships between variables are not linear, whereupon the method of principal components will fail to explain adequately any nonlinear co-variability present in the measurements. An example dataset of this type is shown in figure 2(a), consisting of points sampled from a two-dimensional disc stretched into a three-dimensional shape taking the form of a fishbowl.

Figure 2.

(a)‘Fishbowl’ data (sphere with top cap removed). Nonlinear dimension reduction, with contrasting embeddings of the data of (a) shown. (b) The two-dimensional linear embedding via PCA yields an overlap of points of different colour, indicating a failure to recover the nonlinear structure of the data. (c and d) The embeddings obtained by diffusion maps and Laplacian eigenmaps, respectively; each of these methods successfully recovers the nonlinear structure of the original dataset, correctly ‘unfolding’ it in two dimensions.

In the same vein as PCA, however, most contemporary methods for nonlinear dimension reduction are based on the analysis of an appropriately defined positive semidefinite kernel. Here, we limit ourselves to describing two closely related methods that serve to illustrate the case in point: diffusion maps (4, Coifman et al. 2005) and Laplacian eigenmaps (Belkin & Niyogi 2003).

2.2.1. Diffusion maps

Given input data  having cardinality N and dimension n, along with parameters σ>0 and m a positive integer, the diffusion map algorithm involves first forming a positive semi-definite kernel Q whose (i,j)th entry is given by

having cardinality N and dimension n, along with parameters σ>0 and m a positive integer, the diffusion map algorithm involves first forming a positive semi-definite kernel Q whose (i,j)th entry is given by

| 2.1 |

with ∥xi−xj∥ the standard Euclidean norm on  . If we define a diagonal matrix D whose entries are the corresponding row/column sums of Q as

. If we define a diagonal matrix D whose entries are the corresponding row/column sums of Q as  , the Markov transition matrix P=D−1Q is then computed. This transition matrix describes the evolution of a discrete-time diffusion process on the points of

, the Markov transition matrix P=D−1Q is then computed. This transition matrix describes the evolution of a discrete-time diffusion process on the points of  , where the transition probabilities are given by equation (2.1), with multiplication of Q by D−1 serving to normalize them.

, where the transition probabilities are given by equation (2.1), with multiplication of Q by D−1 serving to normalize them.

As is well known, the corresponding transition matrix after m time steps is simply given by the m-fold product of P with itself; if we write Pm=UΛmU−1, the principal eigenvectors and eigenvalues of this transition matrix are used to embed the data according to Y =UΛm. However, note that, as P is a stochastic matrix, its principal eigenvector is [1 1 … 1]T, with the corresponding eigenvalue equal to unity. This eigenvector–eigenvalue pair is hence ignored for purposes of the embedding, as it does not depend on  .

.

Although P=D−1Q is not symmetric, its eigenvectors can equivalently be obtained via the spectral analysis of the positive semidefinite kernel  : if (λ,u) satisfy Pu=λu, then, if

: if (λ,u) satisfy Pu=λu, then, if  , we obtain

, we obtain

Hence, from this analysis, we see that P and  share identical eigenvalues, as well as eigenvectors related by a diagonal transformation.

share identical eigenvalues, as well as eigenvectors related by a diagonal transformation.

2.2.2. Laplacian eigenmaps

Rather than necessarily computing a dense kernel Q as in the case of diffusion maps, the Laplacian eigenmaps algorithm commences with the computation of a k-neighbourhood for each datum point xi; i.e. the k nearest data points to each xi are found. A weighted graph whose vertices are the data points {x1,x2,…,xN} is then computed, with an edge present between vertices xi and xj if and only if xi is among the k closest points to xj, or vice versa. The weight of each kernel entry is given by Qij=e−∥xi−xj∥2/2σ2 if an edge is present in the corresponding graph, and Qij=0 otherwise, and thus we immediately arrive at a sparsified version of the diffusion maps kernel.

The embedding Y is chosen to minimize the weighted sum of pairwise distances

|

2.2 |

subject to the normalization constraints ∥D1/2yi∥=1, where, as in the case of diffusion maps, D is a diagonal matrix with entries  .

.

Now consider the so-called combinatorial Laplacian of the graph, defined as the positive semidefinite kernel L=D−Q. A simple calculation shows that the constrained minimization of equation (2.2) may be reformulated as

whose solution in turn will consist of the eigenvectors of D−1L with smallest eigenvalues—from which we exclude, as in the case of diffusion maps, the solution proportional to [1 1 … 1]T. By the same argument as employed in §2b(i) above, this analysis is easily related to that of the normalized Laplacian D−1/2LD−1/2.

(c). Computational considerations

Recall our earlier assumption of a collection of N data samples, denoted by the set  , with each sample xi comprising n measurements. An important point of the above analyses is that, in each case, the size of the kernel is dictated by either the number of data samples (diffusion maps, Laplacian eigenmaps) or their dimension (PCA). Indeed, classical and modern spectral methods rely on either of the following:

, with each sample xi comprising n measurements. An important point of the above analyses is that, in each case, the size of the kernel is dictated by either the number of data samples (diffusion maps, Laplacian eigenmaps) or their dimension (PCA). Indeed, classical and modern spectral methods rely on either of the following:

(i) Outer characteristics of the point cloud. Methods such as PCA or Fisher discriminant analysis require the analysis of a kernel of dimension n, the extrinsic dimension of the data.

(ii) Inner characteristics of the point cloud. Multi-dimensional scaling and recent extensions that perform nonlinear embeddings of data points require the spectral analysis of a kernel of dimension N, the cardinality of the point cloud.

In both sets of scenarios, the analysis of large kernels quickly induces a computational burden that is impossible to overcome with exact spectral methods, thereby motivating the introduction of landmark selection and sampling methods.

3. Landmark selection and the Nyström method

Since their introduction, and furthermore as datasets continue to increase in size and dimension, so-called landmark methods have seen wide use by practitioners across various fields. These methods exploit the high level of redundancy often present in high-dimensional datasets by seeking a small (in relative terms) number of important examples or coordinates that summarize the most relevant information in the data; this amounts in effect to an adaptive compression scheme. Separate from this subset, the selection problem is the actual solution of the corresponding spectral analysis task—and this in turn is accomplished via the so-called Nyström extension (Williams & Seeger 2001; Platt 2005).

While the Nyström reconstruction admits the unique property of providing, conditioned upon a set of selected landmarks, the minimal kernel completion with respect to the partial ordering of positive semidefiniteness, the literature is currently open on the question of optimal landmark selection. Choosing the most appropriate set of landmarks for a specific dataset is a fundamental task if spectral methods are to successfully ‘scale up’ to the order of the large datasets already seen in contemporary applications, and expected to grow in the future. Improvements will in turn translate directly to either a more efficient compression of the input (i.e. fewer landmarks will be needed) or a more accurate approximation for a given compression size. While choosing landmarks in a data-adaptive way can clearly offer improvement over approaches such as selecting them uniformly at random (Drineas & Mahoney 2005; Belabbas & Wolfe 2009), this latter approach remains by far the most popular with practitioners (Smola & Schölkopf 2000; Fowlkes et al.2001, 2004; Talwalkar et al. 2008).

While it is clear that data-dependent landmark selection methods offer the potential of at least some improvement over non-adaptive methods such as uniform sampling (Liu et al. 2006), bounds on performance as a function of computation have not been rigorously addressed in the literature to date. One important reason for this has been the lack of a unifying framework to understand the problems of landmark selection and sampling and to provide approximation bounds and quantitative performance guarantees. In this section, we describe an analysis framework for landmark selection that places previous approaches in context, and show how it leads to quantitative performance bounds on Nyström kernel approximation.

(a). Spectral methods and kernel approximation

As noted earlier, spectral methods rely on low-rank approximations of appropriately defined positive semidefinite kernels. To this end, let Q be a real, symmetric kernel matrix of dimension n; we write Q≽0 to denote that Q is positive semidefinite. Any such kernel Q≽0 can in turn be expressed in spectral coordinates as Q=UΛUT, where U is an orthogonal matrix and Λ=diag(λ1,…,λn) contains the real, non-negative eigenvalues of Q, assumed sorted in a non-increasing order.

To measure the error in approximating a kernel Q≽0, we require the following notion of unitary invariance (see Horn & Johnson 1990).

Definition 3.1 (Unitary invarianceUnitary invariance). —

A matrix norm ∥·∥ is termed unitarily invariant if, for all matrices U,V :UTU=I,VTV =I, we have ∥UMVT∥=∥M∥ for every (real) matrix M.

A unitarily invariant norm therefore depends only on the singular values of its argument, and, for any such norm, the optimal rank-k approximation to Q≽0 is given by Qk:=UΛkUT, where Λk=diag(λ1,λ2,…,λk,0,…,0). When a given kernel Q is expressed in spectral coordinates, evaluating the quality of any low-rank approximation  is a trivial task, requiring only an ordering of the eigenvalues. As described in §1, however, the cost of obtaining these spectral coordinates exactly is

is a trivial task, requiring only an ordering of the eigenvalues. As described in §1, however, the cost of obtaining these spectral coordinates exactly is  , which is often too costly to be computed in practice.

, which is often too costly to be computed in practice.

To this end, methods that rely on either the extrinsic dimension of a point cloud or the intrinsic dimension of a set of training examples via its cardinality impose a large computational burden. To illustrate, let  constitute the data of interest. ‘Outer’ methods of the former category employ a rank-k approximation of the matrix

constitute the data of interest. ‘Outer’ methods of the former category employ a rank-k approximation of the matrix  , which is of dimension n. Alternatively, ‘inner’ methods introduce an additional positive-definite function q(xi,xj), such as 〈xi,xj〉 or

, which is of dimension n. Alternatively, ‘inner’ methods introduce an additional positive-definite function q(xi,xj), such as 〈xi,xj〉 or  , and obtain a k-dimensional embedding of the data via the N-dimensional affinity matrix Qij:=q(xi,xj).

, and obtain a k-dimensional embedding of the data via the N-dimensional affinity matrix Qij:=q(xi,xj).

(b). The Nyström method and landmark selection

The Nyström method has found many applications in modern machine learning and data analysis applications as a means of obtaining an approximate spectral analysis of the kernel of interest Q. In brief, the method solves a matrix completion problem in a way that preserves positive semidefiniteness as follows.

Definition 3.2 (Nyström extension). —

Fix a subset

of cardinality k<n, and let QJ denote the corresponding principal submatrix of an n-dimensional kernel Q≽0. Take J={1,2,…,k} without loss of generality and partition Q as follows:

3.1 The Nyström extension then approximates Q by

3.2 Here

and

are always positive semidefinite, being principal submatrices of Q≽0, and Y is a rectangular submatrix of dimension k×(n−k).

If we decompose QJ as  , this corresponds to approximating the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of Q by

, this corresponds to approximating the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of Q by

|

We have that  , and (noting that typically k≪n) the complexity of reconstruction is of order

, and (noting that typically k≪n) the complexity of reconstruction is of order  . Approximate eigenvectors

. Approximate eigenvectors  can be obtained in

can be obtained in  , and can be orthogonalized by an additional projection.

, and can be orthogonalized by an additional projection.

The Nyström method thus serves as a means of completing a partial kernel, conditioned upon a selected subset J of rows and columns of Q. The landmark selection problem becomes that of choosing the subset J of fixed cardinality k such that  is minimized for some unitarily invariant norm, with a lower bound given by ∥Q−Qk∥, where Qk is the optimal rank-k approximation obtained by setting the n−k smallest eigenvalues of Q to zero.

is minimized for some unitarily invariant norm, with a lower bound given by ∥Q−Qk∥, where Qk is the optimal rank-k approximation obtained by setting the n−k smallest eigenvalues of Q to zero.

According to the difference between equations (3.1) and (3.2), the approximation error  can in general be expressed in terms of the Schur complement of QJ in Q, defined as

can in general be expressed in terms of the Schur complement of QJ in Q, defined as  according to the conformal partition of Q in equation (3.1), and correspondingly for an appropriate permutation of rows and columns in the general case.

according to the conformal partition of Q in equation (3.1), and correspondingly for an appropriate permutation of rows and columns in the general case.

With reference to definition 3.2, we thus have the optimal landmark selection problem as follows.

Problem 3.3 (Optimal landmark selection) —

Choose J, with cardinality |J| = k, such that

is minimized.

It remains an open question as to whether or not, for any unitarily invariant norm, this subset selection problem can be solved in fewer than  operations, the threshold above which the exact spectral decomposition becomes the best option. In fact, there is no known exact algorithm other than

operations, the threshold above which the exact spectral decomposition becomes the best option. In fact, there is no known exact algorithm other than  brute-force enumeration in the general case.

brute-force enumeration in the general case.

4. Analysis framework for landmark selection

Attempts to solve the landmark selection problem can be divided into two categories: deterministic methods, which typically minimize some objective function in an iterative or stepwise greedy fashion (Smola & Schölkopf 2000; Ouimet & Bengio 2005; Liu et al. 2006; Zhang & Kwok 2009), for which the resultant quality of kernel approximation cannot typically be guaranteed, and randomized algorithms, which instead proceed by sampling (Williams & Seeger 2001; Fowlkes et al. 2004; Drineas & Mahoney 2005; Belabbas & Wolfe 2009). As we show in this section, those sampling-based methods for which relative error bounds currently exist can all be subsumed within a generalized stochastic framework, which we term annealed determinant sampling.

(a). Nyström error characterization

It is instructive first to consider problem 3.3 in more detail, in order that we may better characterize properties of the Nyström approximation error. To this end, we adopt the trace norm ∥·∥tr as our unitarily invariant norm of interest.

Definition 4.1 Trace norm —

Fix an arbitrary matrix

and let σi(M) denote its ith singular value. Then the trace norm of M is defined as

4.1

As any positive semidefinite kernel Q≽0 admits the Gram decomposition Q=XTX, this implies the following relationship in the Frobenius norm ∥·∥F, to be revisited shortly:

| 4.2 |

The key property of this norm for our purposes follows from the linear–algebraic notion of symmetric gauge functions (see Horn & Johnson 1990).

Lemma 4.2 Dominance of trace norm —

Among all unitarily invariant norms ∥·∥, we have that ∥·∥tr≥∥·∥.

Adopting this norm for problem 3.3, therefore, allows us to provide minimax arguments, and its unitary invariance implies the natural property that results depends only on the spectrum of the kernel Q≽0 under consideration, just as in the case of the optimal rank-k approximant Qk.

To this end, note that any Schur complement is itself positive semidefinite. Recalling from definition 3.2 that the error incurred by the Nyström approximation is the norm of the corresponding Schur complement, and applying the definition of the trace norm as per equation (4.1), we obtain the following characterization of problem 3.3 under trace norm.

Proposition 4.3 (Nyström error in trace norm). —

Fix a subset

of cardinality k<n, and denote by

its complement in{1,2,…,n}. Then, the error in the trace norm induced by the Nyström approximation of an n-dimensional kernel Q≽0 according to definition 3.2, conditioned on the choice of subset J, may be expressed as follows:

4.3 where

denotes rows indexed by J and columns by

.

Proof. —

For any selected subset J, we have that the Nyström error term is given by

according to the notation of proposition 4.3. Now, the Schur complement of a positive semidefinite matrix is always itself positive semidefinite (see Horn & Johnson 1990), and so the specialization of the trace norm for positive semidefinite matrices, as per equation (4.1), applies. We therefore conclude that

4.4 ▪

While each term in the expression of proposition 4.3 depends on the selected subset J, if all elements of the diagonal of Q are equal, then the term  is constant. This has motivated approaches to problem 3.3 based on minimizing exclusively the latter term (Smola & Schölkopf 2000; Zhang & Kwok 2009).

is constant. This has motivated approaches to problem 3.3 based on minimizing exclusively the latter term (Smola & Schölkopf 2000; Zhang & Kwok 2009).

We conclude with an illuminating proposition that follows from the Gram decomposition of equation (4.2).

Proposition 4.4 (Trace norm as regression residual). —

Let Q≽0 have the Gram decomposition Q=XTX, and let X be partitioned as

in accordance with proposition 4.3. Then the Nyström error in the trace norm of equation (4.3 ) is the error sum-of-squares obtained by projecting columns of

on to the closed linear span of columns of XJ.

Proof. —

If Q is positive semidefinite, it admits the Gram decomposition Q=XTX. If we partition X (without loss of generality) into selected and unselected columns

according to a chosen subset J, it follows that

Therefore, the ith diagonal of the residual error follows as

and hence the Nyström error in trace norm is given by the sum of squared residuals obtained by projecting columns of

on to the space spanned by columns of XJ. ▪

(b). Annealed determinantal distributions

With this error characterization in hand, we may now define and introduce the notion of annealed determinantal distributions, which in turn provide a framework for the analysis and comparison of landmark selection and sampling methods.

Definition 4.5 (Annealed determinantal distributions). —

Let Q≽0 be a positive semidefinite kernel of dimension n, and fix an exponent s≥0. Then, for fixed k≤n, Q admits a family of probability distributions defined on the set of all

as follows:

4.5

This distribution is well defined because all principal submatrices of a positive semidefinite matrix are themselves positive semidefinite, and hence have non-negative determinants. The term annealing is suggestive of its use in stochastic computation and search, where a probability distribution or energy function is gradually raised to some non-negative power over the course of an iterative sampling or optimization procedure.

Indeed, for 0<s<1, the determinantal annealing of definition 4.5 amounts to a flattening of the distribution of  , whereas for

, whereas for  it becomes more and more peaked. In the limiting cases, we recover, of course, the uniform distribution on the range of

it becomes more and more peaked. In the limiting cases, we recover, of course, the uniform distribution on the range of  , and, respectively, mass concentrated on its maximal element(s).

, and, respectively, mass concentrated on its maximal element(s).

It is instructive to consider these limiting cases in more detail. Taking s=0, we observe that the method of uniform sampling typically favoured by practitioners (Smola & Schölkopf 2000; Fowlkes et al.2001, 2004; Talwalkar et al. 2008) is trivially recovered, with negligible associated computational cost. By extending the result of Belabbas & Wolfe (2009), the induced error may be bounded as follows.

Theorem 4.6 (Uniform sampling). —

Let Q≽0 have the Nyström extension

, where subset J:|J|=k is chosen uniformly at random. Averaging over this choice, we have

Note that this bound is tight, with equality attained for diagonal Q≽0. Uniform sampling thus averages the effects of all eigenvalues of Q, in contrast to the optimal rank-k approximation obtained by retaining the k principal eigenvalues and eigenvectors from an exact spectral decomposition, which incurs an error in trace norm of only  .

.

In contrast to annealed determinant sampling, uniform sampling fails to place zero probability of selection on subsets J such that  . As the following proposition of Belabbas & Wolfe (2009) shows, the exact reconstruction of rank-k kernels from k-subsets via the Nyström completion requires the avoidance of such subsets.

. As the following proposition of Belabbas & Wolfe (2009) shows, the exact reconstruction of rank-k kernels from k-subsets via the Nyström completion requires the avoidance of such subsets.

Proposition 4.7 (Perfect reconstruction via Nyström extension). —

Let Q≽0 be n×n and of rank k, and suppose that a subset J:|J|=k is sampled according to the annealed determinantal distribution of definition 4.5. Then, for all s>0, the error

incurred by the Nyström completion of equation (3.2) will be equal to zero.

Proof. —

Whenever rank(Q)=k, only full-rank (i.e. rank-k) principal submatrices of Q will be non-singular, and hence admit non-zero determinants. Therefore, for any s>0, these will be the only submatrices selected by the annealed determinantal sampling scheme. By proposition 4.4, the full-rank property implies that the regression error sum-of-squares will in this case be zero, implying that

. ▪

Considering the limiting case as  , we equivalently recover the problem of maximizing the determinant, which is well known to be NP-hard. As

, we equivalently recover the problem of maximizing the determinant, which is well known to be NP-hard. As  , the notion of subset selection based on the maximal determinant admits the following interesting correspondence because if x is a vector-valued Gaussian random variable with a covariance matrix Q, then the Schur complement of QJ×J in Q is the conditional covariance matrix of components

, the notion of subset selection based on the maximal determinant admits the following interesting correspondence because if x is a vector-valued Gaussian random variable with a covariance matrix Q, then the Schur complement of QJ×J in Q is the conditional covariance matrix of components  given xJ.

given xJ.

Proposition 4.8 (Minimax relative entropy). —

Fix an n-dimensional kernel Q≽0 as the covariance matrix of a random vector

and fix an integer k<n. Minimizing the maximum relative entropy of coordinates

, conditional upon having observed coordinates xJ, corresponds to selecting J such that det(QJ×J) is maximized.

Proof. —

The Schur complement SC(QJ×J) represents the covariance matrix of

conditional upon having observed xJ. To this end, we first note the following relationship (Horn & Johnson 1990):

Moreover, for fixed covariance matrix Q, the multi-variate normal distribution maximizes entropy h(x), and hence for SC(QJ×J), we have that

is the maximal relative entropy attainable upon having observed xJ. ▪

To this end, the bound of Goreinov & Tyrtyshnikov (2001) extends to the case of the trace norm as follows.

Theorem 4.9 Determinantal maximization —

Let

denote the Nyström completion of a kernel Q≽0 via subset

. Then

where λk+1(Q) is the (k+1)th largest eigenvalue of Q.

We conclude with a recent result (Belabbas & Wolfe 2009) bounding the expected error for the case s=1, which in turn improves upon the additive error bound of Drineas & Mahoney (2005) for sampling according to the squared diagonal elements of Q.

Theorem 4.10 Determinantal sampling —

Let Q≽0 have the Nyström extension

, where subset J:|J|=k is chosen according to the annealed determinantal distribution of equation (4.5 ) with s=1. Then,

with λi(Q) the ith largest eigenvalue of Q.

This result can be related to that of theorem 4.9, which depends on n−k times λk+1(Q), the (k+1)th largest eigenvalue of Q, rather than the sum of its n−k smallest eigenvalues. It can also be interpreted in terms of the volume sampling approach proposed by Deshpande et al. (2006), applied to the Gram matrix  of an ‘arbitrary’ matrix XJ, as

of an ‘arbitrary’ matrix XJ, as  . By this same argument, Deshpande et al. (2006) show the result of theorem 4.10 to be essentially the best possible.

. By this same argument, Deshpande et al. (2006) show the result of theorem 4.10 to be essentially the best possible.

We conclude by noting that, for most values of s, sampling from the distribution ps(J) presents a combinatorial problem, because of the  distinct k-subsets associated with an n-dimensional kernel Q. To this end, a simple Markov chain Monte Carlo method has been proposed by Belabbas & Wolfe (2009) and shown to be effective for sampling according to the determinantal distribution on k-subsets induced by Q. This Metropolis algorithm can easily be extended to the cases covered by definition 4.5 for all s≥0. We also note that tridiagonal approximations to

distinct k-subsets associated with an n-dimensional kernel Q. To this end, a simple Markov chain Monte Carlo method has been proposed by Belabbas & Wolfe (2009) and shown to be effective for sampling according to the determinantal distribution on k-subsets induced by Q. This Metropolis algorithm can easily be extended to the cases covered by definition 4.5 for all s≥0. We also note that tridiagonal approximations to  can be computed in

can be computed in  operations, and hence offer an alternative to the

operations, and hence offer an alternative to the  cost of exact determinant computation.

cost of exact determinant computation.

5. Case study: application to computer vision

In the light of the range of methods described above for optimizing the landmark selection process through sampling, we now consider a case study drawn from the field of computer vision, in which a low-dimensional manifold structure is extracted from high-dimensional video data streams. This field provides a particularly compelling example, as algorithmic aspects, both of space and time complexity, have historically had a high impact on the efficacy of computer vision solutions.

Applications in areas as diverse as image segmentation (Fowlkes et al. 2004), image matting (Levin et al. 2008), spectral mesh processing (Liu et al. 2006) and object recognition through the use of appearance manifolds (Lee & Kriegman 2005) all rely in turn on the eigendecomposition of a suitably defined kernel. However, at a complexity of  , the full spectral analysis of real-world datasets is often prohibitively costly—requiring in practice an approximation to the exact spectral decomposition. Indeed, the aforementioned tasks typically fall into this category, and several share the common feature that their kernel approximations are obtained in exactly the same way—via the process of selecting a subset of landmarks to serve as a basis for computation.

, the full spectral analysis of real-world datasets is often prohibitively costly—requiring in practice an approximation to the exact spectral decomposition. Indeed, the aforementioned tasks typically fall into this category, and several share the common feature that their kernel approximations are obtained in exactly the same way—via the process of selecting a subset of landmarks to serve as a basis for computation.

(a). The spectral analysis of large video datasets

Video datasets may often be assumed to have been generated by a dynamical process evolving on a low-dimensional manifold, for example a line in the case of a translation, or a circle in the case of a rotation. Extracting this low-dimensional space has applications in object recognition through appearance manifolds (Lee et al. 2005), motion recognition (Blackburn & Ribeiro 2007), pose estimation (Elgammal & Lee 2004) and others. In this context, nonlinear dimension-reduction algorithms (Lin & Zha 2008) are the key ingredients mapping the video stream to a lower dimensional space. The vast majority of these algorithms require one to obtain the eigenvectors of a positive-definite kernel Q of size equal to the number of frames in the video stream, which quickly becomes prohibitive and entails the use of approximations to the exact spectral analysis of Q.

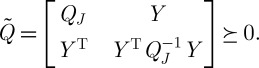

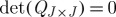

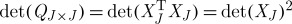

To begin our case study, we first tested the efficacy of the Nyström extension coupled with the subset selection procedures given in §4 on different video datasets. In figure 3, we show the exact embedding in three dimensions, using the diffusion map algorithm (Coifman et al. 2005), of a video from the Honda/UCSD database (Lee et al.2003, 2005), as well as some selected frames. In this video, the subject rotates his head in front of the camera in several directions, with each motion starting from the resting position of looking straight at the camera. We observe that with each of these motions is associated a circular path, and that they all originate from the same area (the lower front-right area) of the graph, which corresponds to the resting position.

Figure 3.

Diffusion maps embedding of the video fuji.avi from the Honda/UCSD database (Lee et al. 2003, 2005), implemented in the pixel domain after data normalization, σ=100.

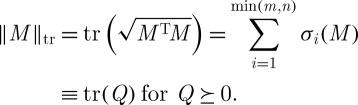

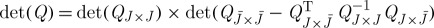

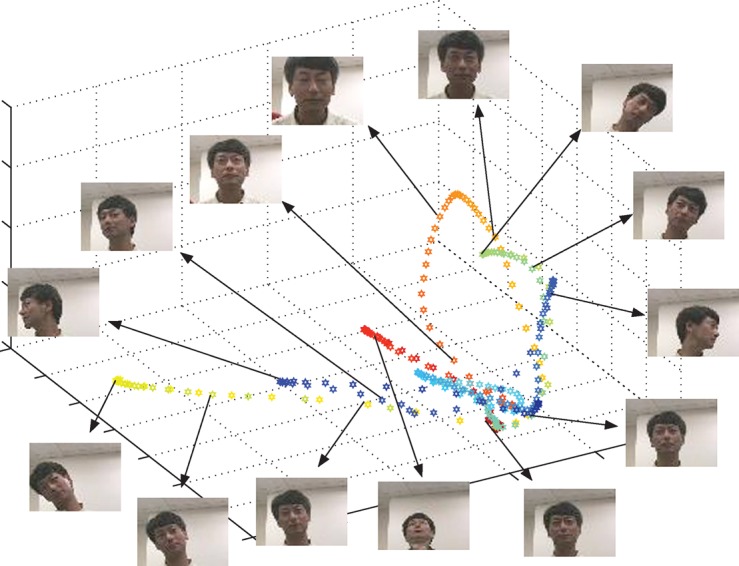

In figure 4, the average approximation error for the diffusion map kernel corresponding to this video is evaluated, for an approximation rank between 2 and 20. The results are averaged over 2000 trials. The sampling from the determinant distribution is done via a Monte Carlo algorithm similar to that of Belabbas & Wolfe (2009) and the determinant maximization is obtained by keeping the subset J with the largest corresponding determinant QJ over a random choice of 2500 subsets. For this setting, sampling according to the determinant distribution yields the best results uniformly across the range of approximations. We observe that keeping the subset with a maximal determinant does not give a good approximation at low ranks. A further analysis showed that in this case the chosen landmarks tend to concentrate around the lower front-right region of the graph, which yields a good approximation locally in this part of the space but fails to recover other regions properly. This behaviour illustrates the appeal of randomized methods, which avoid such pitfalls.

Figure 4.

Average normalized approximation error of the Nyström reconstruction of the diffusion maps kernel obtained from the video of figure 3 using different subset selection methods. Sampling according to the determinant yields overall the best performance. Blue circles, uniform sampling (s=0); red squares, determinantal maximization ( ); black diamonds, determinantal sampling (s=1).

); black diamonds, determinantal sampling (s=1).

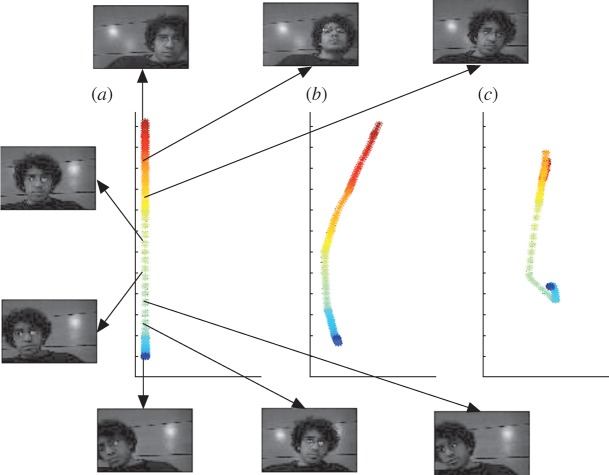

As a subsequent demonstration, we collected video data of the first author moving slowly in front of a camera at an uneven speed. The resulting embedding, given again by the diffusion map algorithm, is a non-uniformly sampled straight line. In this case, we can thus evaluate by visual inspection the effect of an approximation of the diffusion map kernel on the quality of the embedding. This is shown in figure 5, where typical results from different subset selection methods are displayed. We see that sampling according to the determinant recovers the linear structure of the dynamical process, up to an affine transformation, whereas sampling uniformly yields some folding of the curve over itself at the extremities and centre.

Figure 5.

(a) Exact, (b) determinant sampling and (c) uniform sampling diffusion maps embedding of a video showing movement at an uneven speed, implemented in the pixel domain with σ=100 after data normalization. Note that the linear structure of this manifold is recovered almost exactly by the determinantal sampling scheme, whereas it is lost in the case of uniform sampling, where the curve folds over onto itself.

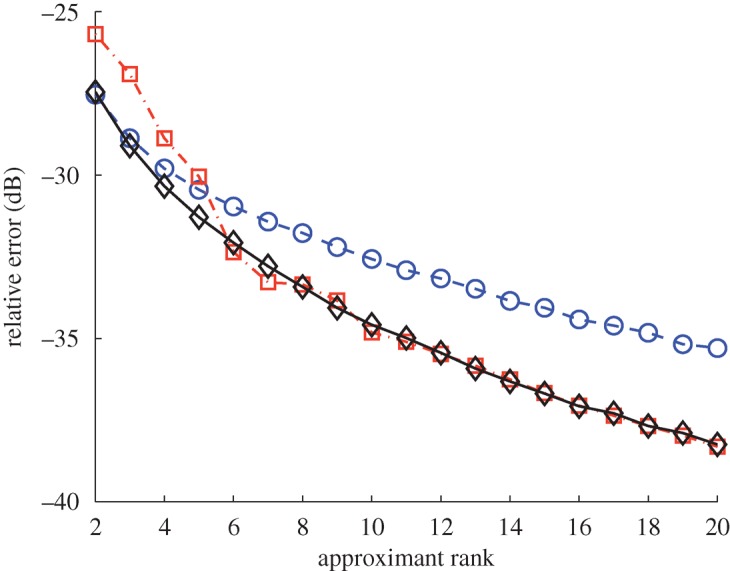

In figure 6, we show the approximation error of the kernel associated with this video averaged over 2000 trials, similar to the previous example. In this case, maximizing the determinant yields the best overall performance. We observe that sampling according to the determinant easily outperforms choosing the subset uniformly at random, lending further credence to our analysis framework and its practical implications for landmark selection and data subsampling.

Figure 6.

Average normalized approximation error of the Nyström reconstruction of the diffusion maps kernel obtained from the video of figure 5 using different subset selection methods. Sampling uniformly is consistently outperformed by the other methods. Blue circles, uniform sampling (s=0); red squares, determinantal maximization ( ); black diamonds, determinantal sampling (s=1).

); black diamonds, determinantal sampling (s=1).

Acknowledgements

This material is based in part upon work supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under grant HR0011-07-1-0007, by the National Institutes of Health under grant P01 CA134294-01 and by the National Science Foundation under grants DMS-0631636 and CBET-0730389. Work was performed in part while the authors were visiting the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences under the auspices of its programme on statistical theory and methods for complex high-dimensional data, for which support is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

One contribution of 11 to a Theme Issue ‘Statistical challenges of high-dimensional data’.

References

- Belabbas M.-A., Wolfe P. J.2009Spectral methods in machine learning and new strategies for very large data sets Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106369–374(doi:1073/pnas.0810600105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin M., Niyogi P.2003Laplacian eigenmaps for dimensionality reduction and data representation Neural Comput. 151373–1396(doi:1162/089976603321780317) [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn J., Ribeiro E.2007Human motion recognition using isomap and dynamic time warping Human motion–understanding, modeling, capture and animation Elgammal A., Rosenhahn B., Klette R. 285–298. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Coifman R. R., Lafon S., Lee A. B., Maggioni M., Nadler B., Warner F., Zucker S. W.2005Geometric diffusions as a tool for harmonic analysis and structure definition of data: diffusion maps Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 1027426–7431(doi:1073/pnas.0500334102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A., Rademacher L., Vempala S., Wang G.2006Matrix approximation and projective clustering via volume sampling Proc. 17th Annual ACM-SIAM Symp. on Discrete Algorithms, Miami, FL 1117–1126. See http://siam.org/meetings/da06/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Donoho D. L., Grimes C.2003Hessian eigenmaps: locally linear embedding techniques for high-dimensional data Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 1005591–5596(doi:1073/pnas.1031596100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drineas P., Mahoney M. W. On the Nyström method for approximating a Gram matrix for improved kernel-based learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2005;6:2153–2175. [Google Scholar]

- Elgammal A., Lee C.-S.2004Inferring 3D body pose from silhouettes using activity manifold learning Proc. IEEE Computer Society Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Washington, DC vol. 2 681–688. See http://cvl.umiacs.umd.edu/conferences/cvpr2004/. [Google Scholar]

- Fowlkes C., Belongie S., Malik J.2001Efficient spatiotemporal grouping using the Nyström method Proc. IEEE Computer Society Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Lihue, HI vol. 1 231–238. See http://vision.cse.psu.edu/cvpr2001/main1.html [Google Scholar]

- Fowlkes C., Belongie S., Chung F., Malik J.2004Spectral grouping using the Nyström method IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 26214–225(doi:1109/TPAMI.2004.1262185) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goreinov S. A., Tyrtyshnikov E. E. The maximal-volume concept in approximation by low-rank matrices. Contemp. Math. 2001;280:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Horn R. A., Johnson C. R. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.; 1990. Matrix analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-C., Kriegman D.2005Online learning of probabilistic appearance manifolds for video-based recognition and tracking Proc. IEEE Computer Society Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Diego, CA vol. 1 852–859.See http://www.cs.duke.edu/cvpr2005/. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-C., Ho J., Yang M., Kriegman D.2003Video-based face recognition using probabilistic appearance manifolds Proc. IEEE Computer Society Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition vol. 1 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-C., Ho J., Yang M., Kriegman D.2005Visual tracking and recognition using probabilistic appearance manifolds Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 99303–331(doi:1016/j.cviu.2005.02.002) [Google Scholar]

- Levin A., Rav-Acha A., Lischinski D.2008Spectral matting IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 301–14(doi:1109/TPAMI.2008.168) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T., Zha H.2008Riemannian manifold learning IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 30796–809(doi:1109/TPAMI.2007.70735) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Jain V., Zhang H.2006Sub-sampling for efficient spectral mesh processing In Proc. 24th Computer Graphics Int. Conf. Nishita T., Peng Q., H.-P. Seidel. pp. 172–184 Lecture Notes in Computer Science, no. 4035. Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Ouimet M., Bengio Y.2005Greedy spectral embedding Proc. 10th Int. Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Christ Church, Barbados 253–260. See http://www.gatsby.ucl.ac.uk/aistats/. [Google Scholar]

- Platt J. C. Proc. 10th Int. Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Christ Church, Barbados. 2005. Fastmap, MetricMap, and Landmark MDS are all Nyström algorithms; pp. 261–268. See http://www.gatsby.ucl.ac.uk/aistats/ . [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Malik J.2000Normalized cuts and image segmentation IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 22888–905(doi:1109/34.868688) [Google Scholar]

- Smola A. J., Schölkopf B. Proc. 17th Int. Conf. on Machine Learning, Palo Alto, CA. 2000. Sparse greedy matrix approximation for machine learning; pp. 911–918. See http://www-csli.stanford.edu/icml2k/ . [Google Scholar]

- Talwalkar A., Kumar S., Rowley H.2008Large-scale manifold learning Proc.IEEE Computer Society Conf. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition ( 10.1109/CVPR.2008.4587670) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum J. B., de Silva V., Langford J. C.2000A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction Science 2902319–2323(doi:1126/science.290.5500.2319) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. K. I., Seeger M.2001Using the Nyström method to speed up kernel machines Advances in neural information processing systems vol. 13Dietterich T. G., Becker S., Ghahramani Z. pp. 682–688. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Kwok J. T.2009Density-weighted Nyström method for computing large kernel eigensystems Neural Comput. 21121–146(doi:1162/neco.2009.11-07-651) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]