Abstract

Neonatal bacterial infection in rats alters the responses to a variety of subsequent challenges later in life. Here we explored the effects of neonatal bacterial infection on a subsequent drug challenge during adolescence, using administration of the psychostimulant amphetamine. Male rat pups were injected on postnatal day 4 (P4) with live Escherichia coli (E. coli) or PBS vehicle, and then received amphetamine (15 mg/kg) or saline on P40. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on micropunches taken from medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus. mRNA for glial and neuronal activation markers as well as pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines were assessed. Amphetamine produced brain region specific increases in many of these genes in PBS controls, while these effects were blunted or absent in neonatal E. coli treated rats. In contrast to the potentiating effect of neonatal E. coli on glial and cytokine responses to an immune challenge previously observed, neonatal E. coli infection attenuates glial and cytokine responses to an amphetamine challenge.

Keywords: Amphetamine, Cytokines, Glia, Neonatal Infection, Adolescence, RT-PCR

Early life events, including exposure to physical and psychological stressors, can have long-lasting effects on an individual’s response to challenges later in life. The early postnatal period in the rat corresponds roughly to the third trimester of prenatal development in the human, and complications including infections can affect up to one-third of pregnancies [11]. Previous work has demonstrated that in adult rats that had experienced neonatal infection on postnatal day 4 (P4) with the bacterium E. coli, an immune challenge with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produced enhanced glial and pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in the hippocampus and plasma [3]. In contrast, adult rats treated on P4 with the same dose of E. coli had attenuated responses to psychological stressors, including reductions in stress-induced plasma corticosterone levels and depressive-like behavior [5]. Thus, neonatal bacterial infection can confer either vulnerability to, or protection from, a later life challenge depending. However, it is unknown what effects neonatal bacterial infection might have on the glial and neuroimmune changes produced by drugs of abuse.

Work in our laboratory [12] and others [20] has demonstrated that abused drugs can produce numerous effects on non-neuronal cell types including astrocytes and microglia, and that glia can modulate drug action [7]. Amphetamines, including d-amphetamine [27], are particularly potent activators of microglia in both mice [27] and humans [25]. Thus we explored the effects of neonatal E. coli infection on a subsequent d-amphetamine challenge during adolescence. We chose adolescence because this is the developmental period in which many recreational drug users are first exposed to drugs [24]. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on tissue from three regions affected by drugs of abuse; that is, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), nucleus accumbens (NAcc), and CA1 subfield of the hippocampus. Previous work in our laboratory has revealed changes in morphine-induced astrocytic and microglial activation in these regions [13]. We tested the hypothesis that neonatal infection would increase the expression of amphetamine-induced glial activation markers and proinflammatory cytokines, as was the case after LPS challenge [5]. Real time RT-PCR was performed to detect mRNA for the microglial membrane protein CD11b, the astroglial marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL) IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, the anti-inflammatory neuroimmune regulatory molecule CD200 and, as well as the effector immediate early gene activity-regulated-cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc), which is primarily neuronal.

Methods

Animals

Pups were derived from Sprague–Dawley rats obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) using previously published procedures [2–6]. The colony was maintained at 22 °C on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle with food and water freely available. All experiments were conducted with protocols approved by the University of Colorado Animal Care and Use Committee. Litters were culled on P4 to 2 females and up to 8 males. Because these experiments build on phenomena that have only been tested in males [2–6] only males pups were used.

Bacterial culture

E. coli culture (ATCC 15746; American Type Culture Collection) vial contents were hydrated and grown overnight in 30 ml of brain–heart infusion (Difco Labs) at 37°C and processed as previously reported [2–6].

Neonatal treatment

Pups were injected subcutaneously (30G needle) on P4 with either 0.1×106 colony forming units (CFU) of live bacterial E. coli per gram body weight suspended in 0.1 ml PBS, or 0.1 ml PBS alone. All pups were removed from the mother at the same time and placed into a clean cage with bedding, injected individually, and returned to the mother as a group. Elapsed time away from the mother was less than 5 min. All pups from a single litter received the same treatment due to concerns over possible cross-contamination from E. coli. Injections were given between 10:00 and 10:30 h. Pups were weaned on P21 into sibling pairs and remained undisturbed until P40. To control for possible litter effects, a maximum of two pups/litter were assigned to a single experimental group. On P40, rats received a single injection of D-amphetamine (Sigma, 15 mg/ml/kg) or saline vehicle. We used the d-amphetamine dose of Moskowitz et al., [19] that was shown to produce protein disaggregation adolescent rats but is lower than those that produce frank toxicity [27]. Each rat in a cage received the same drug treatment. Rats were returned to their home cages after the injection, where they remained until sacrifice 2 hr later. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using previously published procedures [2, 3, 10]. cDNA sequences were obtained from GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Primer sequences were designed using an online Oligo Analysis & Plotting Tool (Qiagen) and tested for sequence specificity using the basic local alignment search tool at NCBI. The following primers were used (gene, forward (F) and reverse (R) sequence, and GenBank accession number):

Arc, F: ACAGAGGATGAGACTGAGGCAC, R: TATTCAGGCTGGGTCCTGTCAC, U19866;

CD11b, F: CTGGGAGATGTGAATGGAG, R: ACTGATGCTGGCTACTGATG, NM_012711;

CD200, F: TGTTCCGCTGATTGTTGGC, R: ATGGACACATTACGGTTGCC, NM_031518;

GAPDH, F: GTTTGTGATGGGTGTGAACC, R: TCTTCTGAGTGGCAGTGATG, M17701;

GFAP, F: AGGGACAATCTCACACAGG, R: GACTCAACCTTCCTCTCCA, AF028784;

IL-1β, F: GAAGTCAAGACCAAAGTGG, R: TGAAGTCAACTATGTCCCG, M98820;

IL-6, F: ACTTCACAGAGGATACCAC, R: GCATCATCGCTGTTCATAC, NM_012589;

IL-10, F: TAAGGGTTACTTGGGTTGCC, R: TATCCAGAGGGTCTTCAGC, NM_012854;

TNF-α, F: CTTCAAGGGACAAGGCTG, R: GAGGCTGACTTTCTCCTG, D00475.

For each experimental sample, triplicate reactions were conducted using published procedures. Gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method [17] relative to the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). No group differences were observed in GAPDH mRNA expression. Because of (mostly nonsignificant) variability in constitutive gene expression between the E. coli and PBS saline groups (Table 1) data were normalized to percent of saline control. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. When significant interactions were found, post-hoc comparisons were made using Student–Neuman–Keuls tests (α set at .05). When significant interactions were not found, we tested our a-priori hypothesis using the more conservative Scheffe’s tests (α set at .05).

Table 1.

Gene expression (relative to GAPDH) in adolescent rats treated neonatally with E. coli or PBS vehicle and during adolescence with saline vehicle.

| Prefrontal Cortex | Nucleus Accumbens | Hippocampus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | PBS | E. Coli | PBS | E. Coli | PBS | E. Coli |

| Arc | 2.38 ± 0.45 | 3.06 ± 0.60 | 2.12 ± 0.35 | 1.76 ± 0.28 | 3.69 ± 0.59 | 6.20 ± 1.13 |

| CD11b | 3.26 ± 0.41 | 2.74 ± 0.52 | 3.39 ± 0.49 | 3.94 ± 0.92 | 2.70 ± 0.54 | 3.01 ± 0.62 |

| CD200 | 1.41 ± 0.15 | 2.04 ± 0.35 | 3.51 ± 0.39 | 5.58 ± 0.35 ** | 6.73 ± 3.06 | 6.75 ± 3.17 |

| GFAP | 2.70 ± 0.50 | 3.64 ± 0.86 | 3.27 ± 0.46 | 3.83 ± 0.36 | 8.55 ± 1.35 | 13.67 ± 2.37 |

| IL-1β | 2.63 ± 0.46 | 9.95 ± 3.91 | 2.06 ± 0.39 | 2.29 ± 0.65 | 7.33 ± 1.56 | 12.10 ± 3.68 |

| IL-6 | 1.63 ± 0.24 | 1.85 ± 0.30 | 3.66 ± 0.60 | 3.75 ± 0.59 | 3.94 ± 0.85 | 6.67 ± 2.72 |

| IL-10 | 4.02 ± 1.14 | 3.61 ± 1.33 | 8.19 ± 2.88 | 9.89 ± 6.26 | 12.71 ± 3.95 | 24.77 ± 7.27 |

| TNFα | 3.48 ± 0.56 | 5.15 ± 0.91 | 4.03 ± 0.87 | 3.58 ± 0.40 | 3.11 ± 0.53 | 6.20 ± 1.23 * |

Values are means ± SEMs of 6 to 8 rats.

p < .05,

p < .01, E. coli different from PBS control.

Results

Relative mRNA expression in the mPFC, NAcc, and CA1 of rats treated on P4 with E. coli or PBS, and in adolescence with saline vehicle

Table 1 shows expression of all the genes assessed. One-way ANOVA revealed that neonatal E. coli treated rats had greater CD200 mRNA expression than neonatal PBS controls in the NAcc, F(1,12) = 15.34, p < .01. Finally, neonatal E. coli treated rats had greater TNFα mRNA expression than neonatal PBS controls in the CA1, F(1,12) = 4.88, p < .05.

Normalized mRNA expression in the mPFC, NAcc, and CA1 of rats treated on P4 with E. coli or PBS, and in adolescence with amphetamine or saline

mPFC

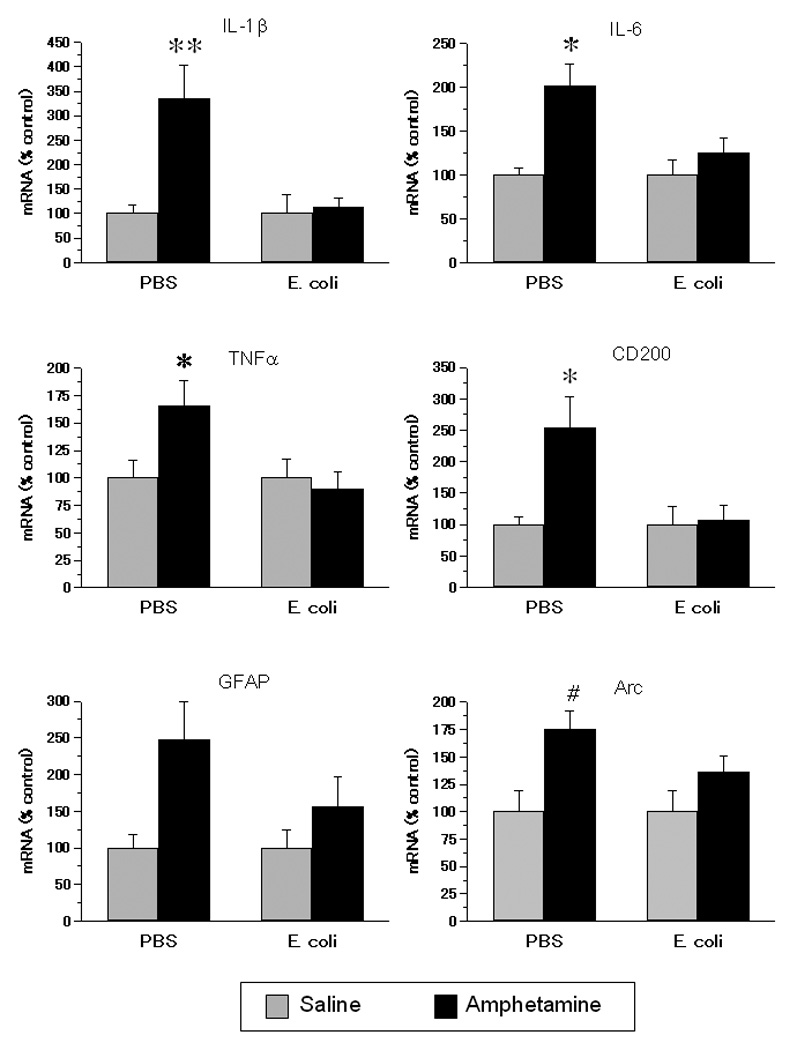

Amphetamine increased the expression of mRNA for IL1β, IL6, TNFα, CD200, Arc, and GFAP only in rats treated neonatally with PBS (Fig. 1). Two-way ANOVA revealed several neonatal treatment by adolescent treatment interactions: IL1β, F(1,24) = 6.68, p < .01; IL6, F(1,25) = 4.44, p < .05; TNFα, F(1,24) = 4.50, p < .05; and CD200, F(1,25) = 5.33, p < .05. In each of these cases post-hoc tests indicated that the PBS + amphetamine group had greater mRNA levels than all other groups. There was a near significant neonatal by adolescent treatment interaction for Arc mRNA, F(1,25) = 3.83, p = .06. A priori tests indicated that the PBS + amphetamine group had greater levels of mRNA than PBS + saline. There was a main effect of adolescent treatment on GFAP, F(1,26) = 7.16, p < .05; amphetamine increased GFAP mRNA expression. There were no significant main effects or interactions for CD11b or IL-10 (not shown).

Figure 1.

Gene expression in the mPFCof rats exposed on P4 to E. coli or PBS and to amphetamine or saline in adolescence. Adolescent amphetamine increased gene expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, CD200, and Arc, and this increase was absent or attenuated in neonatal E. coli treated rats. Data are normalized to a percent of each neonatal treatment group’s saline control. Values are means ± SEMs of 6 to 8 rats/group. ** Significantly different from all other groups, p < .01. * Significantly different from all other groups, p < .05. # Significantly different from PBS + saline, p < .05.

NAcc

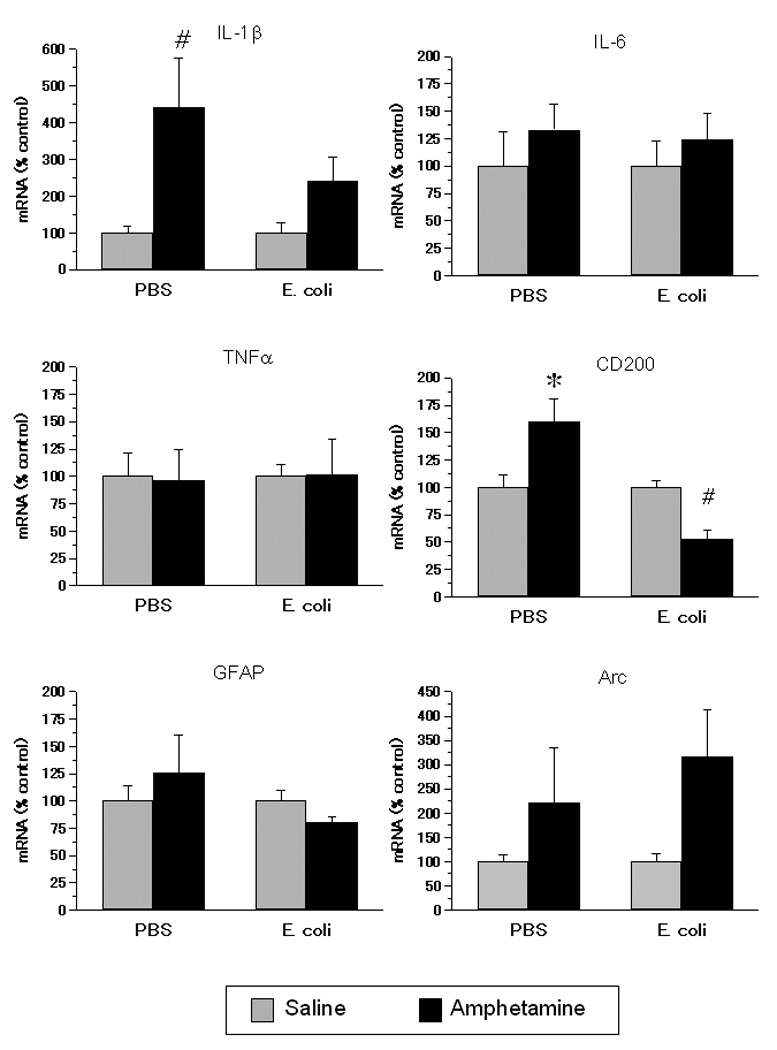

Amphetamine increased the expression of mRNA for IL1β and CD200 in rats treated neonatally with PBS, while decreasing expression of CD200 mRNA in neonatal E. coli treated rats (Fig. 2). There was a main effect of adolescent treatment on IL1β mRNA, F(1,23) = 12.99, p <.01; a priori tests indicated that the PBS + amphetamine group had greater levels of IL1β mRNA than PBS + saline. There was a neonatal by adolescent treatment interaction for CD200 mRNA, F(1,25) = 11.36, p < .01; post-hoc tests indicated that the PBS + amphetamine group had greater CD200 mRNA levels than all other groups and E. coli + amphetamine had lower CD200 mRNA levels than E. coli + saline. There was a main effect of adolescent treatment F(1,25) = 5.14, p < .05; amphetamine increased Arc mRNA expression. There were no main effects or interactions on mRNA for IL6 or GFAP (Fig. 2), or on CD11b, IL-10, or TNFα mRNA expression (not shown).

Figure 2.

Gene expression in the NAcc of rats exposed on P4 to E. coli or PBS and to amphetamine or saline in adolescence. Adolescent amphetamine increased gene expression of IL-1β and CD200, and this increase was attenuated or reversed in neonatal E. coli treated rats. Data are normalized to a percent of each neonatal treatment group’s saline control. Values are means ± SEMs of 5 to 8 rats/group. * Significantly different from all other groups, p < .05. # Significantly different from saline-injected rats within same neonatal group, p < .05.

CA1

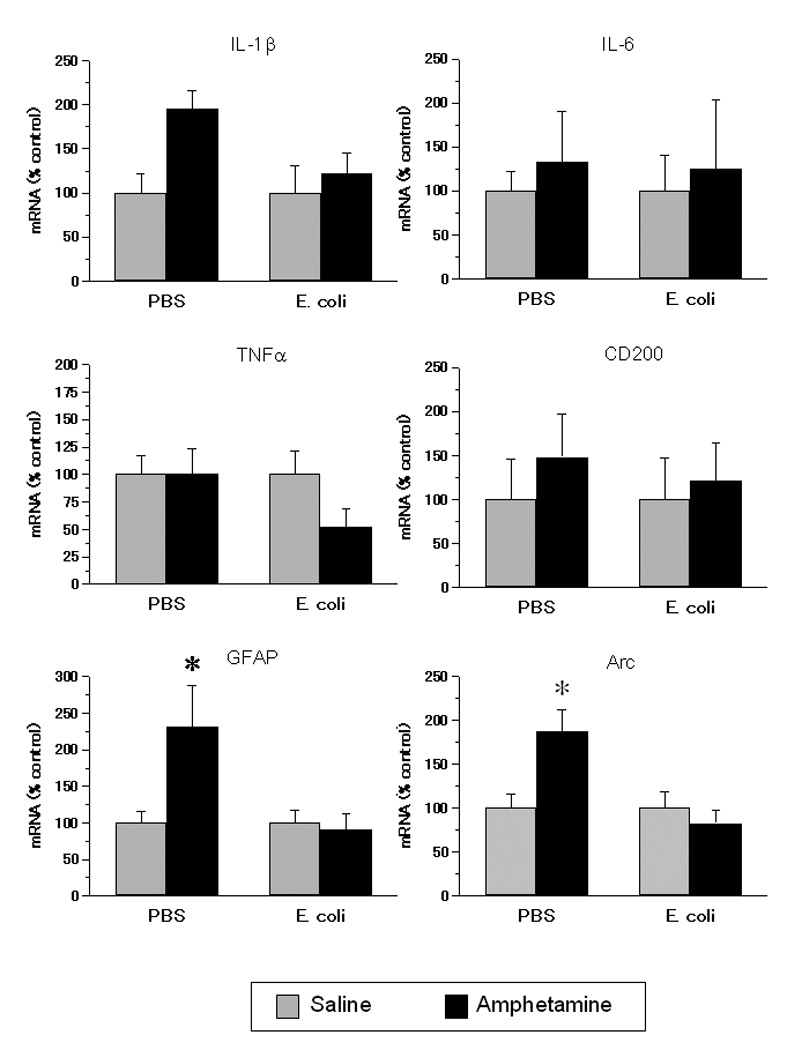

Amphetamine increased the expression of mRNA for Arc and GFAP only in rats treated neonatally with PBS, and increased the expression of IL1β mRNA overall (Fig. 3). There were neonatal by adolescent treatment interactions for GFAP, F(1,26) = 6.10, p < .05, and Arc, F(1,26) = 7.97, p < .01. Post-hoc tests indicated that the PBS + amphetamine group had greater Arc and GFAP mRNA levels than all other groups. There was also a main effect of adolescent treatment on IL1β mRNA, F(1,23) = 5.58, p < .05; amphetamine increased IL1β mRNA expression. There were no main effects or interactions on IL6 or CD200 (Fig. 3), or on CD11b, IL-10, or TNFα mRNA expression (not shown).

Figure 3.

Gene expression in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of rats exposed on P4 to E. coli or PBS and to amphetamine or saline in adolescence. Adolescent amphetamine increased gene expression of GFAP and Arc, and this increase was absent in neonatal E. coli treated rats. Data are normalized to a percent of each neonatal treatment group’s saline control. Values are means ± SEMs of 6 to 8 rats/group. * Significantly different from all other groups, p < .05.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that neonatal bacterial infection largely eliminated the neuroinflammatory effects of an acute amphetamine challenge in adolescence. A single moderately high dose of amphetamine administered to adolescent rats produced increases in the gene expression of markers for glial and neuronal activation, as well as increases in proinflammatory cytokines, in a brain region dependent manner. These effects of amphetamine were blunted or absent in adolescent rats that had been treated neonatally with E. coli. In no cases were mRNA levels significantly greater after amphetamine in rats treated neonatally with E. coli compared to their saline-treated control group. Thus these results are more similar to the effects of neonatal E. coli infection on adult responses to psychological stress, which were blunted [5], than on adult responses to LPS, which were enhanced [3], and provide further support to the notion that outcomes after neonatal infection may be either protected or impaired [5].

It is currently appreciated that microglia and astrocytes are heterogeneous within the brain, and regional differences in the constitutive [22] and induced [9] expression of pro-inflammatory molecules have been reported. Cultured microglial cells from various brain regions express proinflammatory molecules differentially, suggesting that microlia are preconditioned to the environment from which they were obtained [22]. Regional differences in astrocyte function and in glial-neuronal interactions are also known to occur [8]. In the present study, the mPFC was the region most responsive to amphetamine in rats treated neonatally with PBS vehicle. Amphetamine increased the expression of mRNA for IL-1β IL-6, and TNFα, CD200, and Arc. In the NAcc, amphetamine produced increases in expression of mRNA for IL1β as well as for CD200, the latter of which was decreased in rats treated neonatally with E. coli. In the CA1, amphetamine produced increases in IL-1β, GFAP and Arc.

Numerous studies have investigated the effects of amphetamine on immune responses in the periphery [e.g. 21] but much less is known of amphetamine’s impact on immune responses in the CNS. The current results are the first to demonstrate effects of amphetamine on several genes involved in neuroimmune function and glial/neuronal interactions in the mPFC, NAcc, and CA1. In adolescent rats treated neonatally with PBS vehicle, amphetamine increased gene expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL1β, IL-6, and TNFα in the mPFC, and IL1β expression was also increased in the NAcc and CA1. Amphetamine had no effect on these genes in rats treated neonatally with E. coli. In the CNS, proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β are primarily produced by glia and have roles in both neuroimmune function and neuromodulation [28]. Although proinflammatory cytokines can be neuroprotective under some conditions, it has been suggested that the convergence of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα produces neurotoxicity [18]. Amphetamines, including d-amphetamine [23], are known to cause degeneration in numerous brain regions in rats and humans [1], and neuroinflammation may be, at least in part, responsible. The attenuation of amphetamine-induced proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in rats treated neonatally with E. coli suggests that immune activation early in life may produce protection against amphetamine-induced neurodegeneration, although future experiments are required to support this proposal.

It is interesting to note that in the mPFC and the NAcc both proinflammatory cytokines and the anti-inflammatory molecule CD200 were increased after amphetamine in rats treated neonatally with PBS. CD200 may have increased as a compensatory, defensive response to the increased proinflammatory cytokines produced by amphetamine. Amphetamine also increased markers of neuronal (Arc) and astrocytic (GFAP) activation in rats treated neonatally with PBS. It has previously been demonstrated that d-amphetamine increases Arc in the PFC [15]. Arc is associated with neuronal plasticity [15], and the attenuation of amphetamine-induced Arc supports the notion that neonatal E. coli produces long-lasting reductions in neuronal plasticity [2]. The present results suggest that this may include plasticity associated with adaptations to drug exposure. A similar pattern was observed for GFAP, which has also been shown to be increased by amphetamine in several brain regions [14].

There were no amphetamine-induced increases in CD11b, a component of complement receptor 3 and a frequently used marker of microglial activation. CD11b is increased by exposure to a number of amphetamines, including d-amphetamine, but this increase peaks at 24–48 hrs after amphetamine and has only been observed after repeated or very high doses [27]. In a preliminary study(data not shown), we assessed cd11b, GFAP, and IL-1β mRNA expression in the same brain regions assessed here, 24 hr after 15 mg/kg d-amphetamine in adolescent rats that had been neonatally treated with E. coli or PBS, and observed slight amphetamine-induced increases in cd-11b and significant amphetamine-induced increases in GFAP in the mPFC and NAcc, but only in PBS treated rats.

Previous work using the same neonatal E. coli exposure verified that this exposure produces a robust immune response both in the CNS and in the periphery that are resolved by 72 hr after the injection [3]. The results of the present study may be explained by the “hygiene hypothesis”, which posits that the developing immune system should be exposed to some microbial stimulation early in life in order to mature correctly and thus develop tolerance to environmental toxins encountered later in life [26]. A corollary to this is that overprotection against pathogens in early life can lead to later hypersensitivity [26]. However, early exposure to pathogens can also cause hypersensitivity, and can create a state of vulnerability in which a later challenge can act synergistically with the early challenge to produce pathology (the “multiple hit” hypothesis [16]. The impact of early exposure to pathogens on the later neuroimmune response to drugs of abuse is almost completely unexplored. Nonetheless, it is clear that early exposure to E. coli can produce either tolerance or sensitization to different types of challenges, such as tolerance to the effects of amphetamine in the current study and to psychological stress in a previous study [5], but sensitization to the effects of LPS [3]. It is possible that the attenuation of amphetamine’s effects observed here in rats treated neonatally with E. coli are related to the attenuation of stress-induced corticosterone in adult rats treated neonatally with E.coli [5], and that sensitization occurs only with an immune or immune-like challenge, although this remains to be determined.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a NARSAD Young Invesigator Award (S.T.B.) and NIH grants DA013159 (S.F.M.) and MH76320 (S.D.B.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baicy K, London ED. Corticolimbic dysregulation and chronic methamphetamine abuse. Addiction. 2007;102 Suppl 1:5–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilbo SD, Barrientos RM, Eads AS, Northcutt A, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Early-life infection leads to altered BDNF and IL-1beta mRNA expression in rat hippocampus following learning in adulthood. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilbo SD, Biedenkapp JC, Der-Avakian A, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Neonatal infection-induced memory impairment after lipopolysaccharide in adulthood is prevented via caspase-1 inhibition. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8000–8009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1748-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilbo SD, Levkoff LH, Mahoney JH, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF. Neonatal infection induces memory impairments following an immune challenge in adulthood. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:293–301. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilbo SD, Yirmiya R, Amat J, Paul ED, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Bacterial infection early in life protects against stressor-induced depressive-like symptoms in adult rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland ST, Beckley JT, Young S, Tsang V, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Bilbo SD. Enduring consequences of early-life infection on glial and neural cell genesis within cognitive regions of the brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland ST, Hutchinson MR, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. The Glial Activation Inhibitor AV411 Reduces Morphine-Induced Nucleus Accumbens Dopamine Release. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denis-Donini S, Glowinski J, Prochiantz A. Glial heterogeneity may define the three-dimensional shape of mouse mesencephalic dopaminergic neurones. Nature. 1984;307:641–643. doi: 10.1038/307641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Depino A, Ferrari C, Pott Godoy MC, Tarelli R, Pitossi FJ. Differential effects of interleukin-1beta on neurotoxicity, cytokine induction and glial reaction in specific brain regions. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;168:96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank MG, Der-Avakian A, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF. Stress-induced glucocorticoids suppress the antisense molecular regulation of FGF-2 expression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnier Y, Coumans AB, Jensen A, Hasaart TH, Berger R. Infection-related perinatal brain injury: the pathogenic role of impaired fetal cardiovascular control. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:450–459. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchinson MR, Bland ST, Johnson KW, Rice KC, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Opioid-induced glial activation: mechanisms of activation and implications for opioid analgesia, dependence, and reward. ScientificWorldJournal. 2007;7:98–111. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutchinson MR, Lewis SS, Coats BD, Skyba DA, Crysdale NY, Berkelhammer DL, Brzeski A, Northcutt A, Vietz CM, Judd CM, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. Reduction of opioid withdrawal and potentiation of acute opioid analgesia by systemic AV411 (ibudilast) Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakab RL, Bowyer JF. Parvalbumin neuron circuits and microglia in three dopamine-poor cortical regions remain sensitive to amphetamine exposure in the absence of hyperthermia, seizure and stroke. Brain Res. 2002;958:52–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klebaur JE, Ostrander MM, Norton CS, Watson SJ, Akil H, Robinson TE. The ability of amphetamine to evoke arc (Arg 3.1) mRNA expression in the caudate, nucleus accumbens and neocortex is modulated by environmental context. Brain Res. 2002;930:30–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling Z, Chang QA, Tong CW, Leurgans SE, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Rotenone potentiates dopamine neuron loss in animals exposed to lipopolysaccharide prenatally. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maccioni RB, Rojo LE, Fernandez JA, Kuljis RO. The role of neuroimmunomodulation in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moskowitz MA, Weiss BF, Lytle LD, Munro HN, Wurtman J. D-amphetamine disaggregates brain polysomes via a dopaminergic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:834–836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narita M, Miyatake M, Shibasaki M, Shindo K, Nakamura A, Kuzumaki N, Nagumo Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence of astrocytic modulation in the development of rewarding effects induced by drugs of abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2476–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunez-Iglesias MJ, Castro-Bolano C, Losada C, Pereiro-Raposo MD, Riveiro P, Sanchez-Sebio P, Mayan-Santos JM, Rey-Mendez M, Freire-Garabal M. Effects of amphetamine on cell mediated immune response in mice. Life Sci. 1996;58:PL 29–PL 33. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren L, Lubrich B, Biber K, Gebicke-Haerter PJ. Differential expression of inflammatory mediators in rat microglia cultured from different brain regions. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;65:198–205. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan LJ, Linder JC, Martone ME, Groves PM. Histological and ultrastructural evidence that D-amphetamine causes degeneration in neostriatum and frontal cortex of rats. Brain Res. 1990;518:67–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90955-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAHMSA. Results from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Office of Applied Studies); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5756–5761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strachan DP. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the "hygiene hypothesis". Thorax. 2000;55 Suppl 1:S2–S10. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.suppl_1.s2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas DM, Dowgiert J, Geddes TJ, Francescutti-Verbeem D, Liu X, Kuhn DM. Microglial activation is a pharmacologically specific marker for the neurotoxic amphetamines. Neurosci Lett. 2004;367:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins LR, Maier SF. Immune regulation of central nervous system functions: from sickness responses to pathological pain. J Intern Med. 2005;257:139–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]