Abstract

The Greig Health Record is an evidence-based health promotion guide for clinicians caring for children and adolescents aged six to 17 years. It is meant to provide a template for periodic health visits that is easy to use and is easily adaptable for electronic medical records. On the Greig Health Record, where possible, evidence-based information is displayed, and levels of evidence are indicated in boldface type for good evidence and italics for fair evidence.

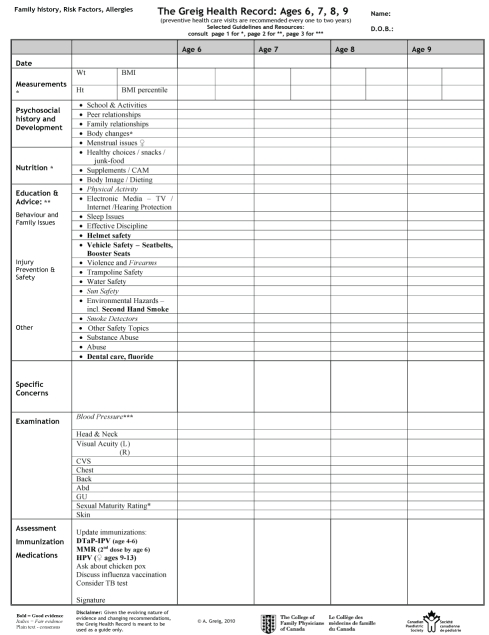

Checklist templates include sections for weight, height and body mass index; psychosocial history and development; nutrition; education and advice; specific concerns; examination; and assessment, immunization and medications. Included with the checklist tables are three pages of selected guidelines and resources. Regular updates to the statement and tool are planned. The Greig Health Record is available in English only at www.cps.ca/english/CP/PreventiveCare.htm.

Keywords: Adolescents, Child health services, Children, Counselling, Evidence-based practice, Forms and records, Preventive health care, Primary prevention, Screening

Abstract

Le relevé médical Greig est un guide probant de promotion de la santé à l’intention des cliniciens qui s’occupent d’enfants et d’adolescents de six à 17 ans. Il est conçu pour servir de modèle facile à utiliser lors des visites médicales périodiques et pour être adapté aux dossiers médicaux électroniques. Dans la mesure du possible, le relevé médical Greig contient l’information probante, et les preuves sont indiquées en caractères gras lorsqu’elles sont de bonne qualité et en italiques lorsqu’elles sont de qualité acceptable.

Les modèles de listes de vérification contiennent des volets sur le poids, la taille, l’indice de masse corporelle, les antécédents psychosociaux et le développement, l’alimentation, l’éducation et les conseils, les inquiétudes particulières, l’examen, l’évaluation, la vaccination et les médicaments. Ces listes de vérification s’accompagnent de trois pages de lignes directrices et ressources sélectionnées. On prévoit apporter des mises à jour régulières au document de principes et au relevé médical. On peut obtenir le relevé médical Greig, en anglais, à l’adresse www.cps.ca/english/CP/PreventiveCare.htm.

Français en page 160

Health care providers appreciate tools that help streamline office visits and serve as an aide-mémoire for the application of evidence-based guidelines. The Rourke Baby Record is an excellent example of such a tool (1). Searches for a similar tool for periodic health visits for an older child and adolescent were unsuccessful in finding an appropriate model. To fill this gap, the Greig Health Record templates were created using the model of the Rourke Baby Record (1). It is hoped that these templates will provide a framework for standardized visits, provoke discussion and perhaps stimulate research.

STATEMENT DEVELOPMENT

The present statement was developed by first searching for available tools and recommendations for periodic health visits for children and adolescents aged six to 17 years. PubMed searches were performed using the terms “preventive services”, “prevention”, “screening” and “health promotion” in the years 1987 to 2009. It was hoped that a tool would be found that was evidence based, simple to use, easy for year-to-year comparison by displaying data in column form, and easily adaptable for electronic medical records. No such tools were found, but major guidelines have been produced by the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination (2), the United States Preventive Services Task Force (3), the American Academy of Pediatrics (4), the American Academy of Family Practice and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau through Bright Futures (5), and the American Medical Association through the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (6).

Common elements were noted and the literature was reviewed for each element to determine its level of evidence. This included a formal review by a clinical paediatric epidemiologist (Dr E Constantin).

Checklist tables for the Greig Health Record are a synthesis of compiled information to form an evidence-based tool that can be used for periodic health visits.

TEMPLATE LAYOUT

In the Greig Health Record, checklist templates are divided into three age ranges: six to nine years, 10 to 13 years and 14 to 17 years inclusive. Headings for sections include weight, height and body mass index; psychosocial history and development; nutrition; education and advice; specific concerns; examination; and assessment, immunization and medications (Figure 1). While pages were divided arbitrarily into early, mid and late groupings, it is important to remember that children develop at different rates and screening questions should be tailored to the individual (7).

Figure 1).

Sample chart from the Greig Health Record. Available in English only

A small area for family history was included on the top left-hand corner of the templates to assist in the identification of children at risk for conditions such as mood disorders, cardiovascular disease and diabetes (8,9). Other risk factors and allergies can also be recorded in this section.

Note that for the physical examination section, consensus opinion supports the inclusion of height, weight, blood pressure and visual acuity screening. Also included are headings for other examinations because these may be useful for case finding and should be used at the discretion of the clinician.

Included with the checklist tables are three pages of selected guidelines and resources related to preventive care visits. The second of these pages focuses on safety and Internet resources, and is designed for easy copying as a handout for patients and parents. The elements on the checklist are labelled with a star or stars to indicate the page location for related materials.

TEMPLATE USE, VISIT STRUCTURE AND CONFIDENTIALITY

In the absence of compelling data, the present statement recommends that visits occur every one to two years based on a consensus recommendation. This interval is in common use and is recommended for height and weight measurements (10,11). The American Academy of Pediatrics (Bright Futures) and the American Medical Association recommend yearly preventive health visits, but other guidelines do not specify frequency because the recommendation is not evidence based (4,12,13). In healthy younger children, there is some evidence to suggest that reducing the number of health promotion visits does not result in adverse outcomes (14).

It is important to consider and counsel on special issues pertaining to the adolescent (15). It may be useful to review references for interviewing and examining adolescents (16–18). It is generally recommended that at least part of the visit with the adolescent be conducted in private, with parents or guardians excused. Confidentiality is central to a successful therapeutic relationship (19). While there are variations among provinces, Canadian common-law minors can give informed consent to therapeutic medical treatment provided they understand and appreciate the proposed treatment, the attendant risks and possible consequences (16,20,21). It is important that the adolescent understand the scope and limitations of this confidentiality, and that exceptions exist in cases of homicidal or suicidal ideation and emotional, physical or sexual abuse (19).

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE AND LIMITATIONS

Evidence-based information for children and adolescents aged six to 17 years is lacking, and there is little agreement among guidelines (22,12). Decisions for inclusion of elements were based primarily on consensus opinions and review of existing guidelines. Where possible, evidence-based information was used and levels of evidence were indicated.

The support for each element is noted in boldface type for good evidence (grade A), italics for fair evidence (grade B) and normal typeface for consensus recommendations (grade C) (23). Note that the grade of evidence indicated reflects the usefulness of each manoeuvre, not whether office-based counselling was found to be effective for each manoeuvre. For example, the use of bicycle helmets is clearly effective in reducing head injuries; however, evidence that office-based counselling increases use is not consistent among studies (24–26). There are few studies on the effectiveness of office-based counselling for individual elements.

There is good evidence for the use of bicycle helmets, seatbelts and booster seats, regular dental care and avoidance of second-hand smoke. There is good evidence to support immunizations as per current Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Advisory Committee on Immunization guidelines. There is fair evidence for screening for major depressive disorder in adolescents, promotion of physical activity, avoidance of firearms in the home, safe sun practices and use of home smoke detectors. There is also fair evidence for blood pressure measurement screening. Of note, there is evidence to support the exclusion of counselling for breast and testicular self-examinations as well as screening manoeuvres for scoliosis.

Growth charts and immunization record pages are not included in the Greig Health Record because they can be found with the Rourke Baby Record (1).

It is important to remember that the preventive health visit is not the only opportunity to address prevention. Not all elements in each section must be covered in each visit. It is expected that clinicians will use their discretion in selecting topics to discuss with each patient and the timing of the discussions.

The Greig Health Record is an evidence-based health supervision guide for clinicians caring for children and adolescents aged six to 17 years. It is meant to provide a template for periodic health visits and anticipatory guidance. Given the evolving nature of evidence and changing recommendations, the Greig Health Record is meant to be used as a guide only. Regular updates to the statement and tool are planned.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded, in part, by a Janus Research Grant from the College of Family Physicians of Canada. The present position statement was reviewed by the Adolescent Health, Community Paediatrics, Infectious Diseases and Immunization, Injury Prevention and Psychosocial Paediatrics Committees of the Canadian Paediatric Society, and by the Joint Action Committee on Child and Adolescent Health of the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Canadian Paediatric Society.

Footnotes

ENDORSEMENT: The College of Family Physicians of Canada endorses the Greig Health Record and its supporting literature.

COMMUNITY PAEDIATRICS COMMITTEE

Members: Drs Minoli Amit, St Martha’s Regional Hospital, Antigonish, Nova Scotia; Carl Cummings, Montreal, Quebec; Barbara Grueger, Whitehorse General Hospital, Whitehorse, Yukon; Mark Feldman, Toronto, Ontario (Chair); Mia Lang, Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta; Janet Grabowski, Winnipeg, Manitoba (Board Representative)

Liaison: Dr David Wong, Summerside, Prince Edward Island (Canadian Paediatric Society, Community Paediatrics Section)

Consultants: Drs Anita Greig, Toronto, Ontario; Hema Patel, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Quebec

Principal authors: Drs Anita Greig, Toronto, Ontario; Evelyn Constantin, The Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Quebec; Ms Sarah Carsley, Westmount, Quebec; Dr Carl Cummings, Montreal, Quebec

The recommendations in this statement do not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate. All Canadian Paediatric Society position statements are reviewed, revised or retired as needed on a regular basis. For the most current version, please consult the “Position Statements” section of the CPS Web site (www.cps.ca/english/publications/statementsindex.htm).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rourke LL, Leduc DG, Rourke JT.Rourke Baby Record: Evidence-based infant/child health maintenance guide, 2006. <www.rourkebabyrecord.ca> (Accessed on January 28, 2010).

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada The Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The Canadian Guide to Clinical Preventive Health Care, 1994. <www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/clinic-clinique/index-eng.php> (Accessed on January 28, 2010).

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2009: Recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. <www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm> (Accessed on January 28, 2010).

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Bright Futures Steering Committee Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1376. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagen JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd edn. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elster AB, Kuznes NJ. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS): Recommendations and Rationale. American Medical Association. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacks D, Canadian Paediatric Society, Adolescent Health Committee Age limits and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8:577. doi: 10.1093/pch/8.9.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Laraque D, GLAD-PC Steering Group Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299–312. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valdez R, Greenlund KJ, Khoury MJ, Yoon PW. Is family history a useful tool for detecting children at risk for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? A public health perspective. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S78–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1010G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montalto NJ. Implementing the guidelines for adolescent preventive services. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:2181–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dietitians of Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, The College of Family Physicians of Canada, and Community Health Nurses of Canada Promoting optimal monitoring of child growth in Canada: Using the new World Health Organization growth charts – Executive Summary. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richmond TK, Freed GL, Clark SJ, et al. Guidelines for adolescent well care: Is there consensus? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:365–70. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000236383.41531.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Medical Association Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS). Recommendations Monograph, 1997. <www.ama-assn.org/ama/upload/mm/39/gapsmono.pdf> (Accessed on January 28, 2010).

- 14.Dinkevich E, Hupert J, Moyer VA. Evidence based well child care. BMJ. 2001;323:846–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7317.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein JD, Matos Auerbach M. Improving adolescent health outcomes. Minerva Pediatr. 2002;54:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacks D, Westwood M. An approach to interviewing adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8:554–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westwood M, Pinzon J. Adolescent male health. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:31–6. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant C, Elliott A, Meglio GD, Lane M, Norris M. What teenagers want: Tips on working with today’s youth. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:15–8. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dibden L, Kaufman M. Confidentiality for adolescents in the patient/physician relationship. Paediatr Child Health. 1997;2:19–20. doi: 10.1093/pch/2.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morton WJ, Westwood M. Informed consent in children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 1997;2:329–33. doi: 10.1093/pch/2.5.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison C, Canadian Paediatric Society, Bioethics Committee Treatment decisions regarding infants, children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2004;9:99–103. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyer VA, Butler M. Gaps in the evidence for well-child care: A challenge to our profession. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1511–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canadian Task Force of Preventive Health Care New grades for recommendations from the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 2003;169:207–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cushman R, James W, Waclawik H. Physicians promoting bicycle helmets for children: A randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:1044–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.8.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiGuiseppi CG, Rivara FP, Koepsell T, Polissar L. Bicycle helmet use by children. Evaluation of a community-wide helmet campaign. JAMA. 1989;262:2256–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens MM, Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Tosteson TD, Mott LA, Starr P. A pediatric, practice-based, randomized trial of drinking and smoking prevention and bicycle helmet, gun, and seatbelt safety promotion. Pediatrics. 2002;109:490–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]