Abstract

Context:

Organizational effectiveness and the continuity of patient care can be affected by certain levels of attrition. However, little is known about the retention and attrition of female certified athletic trainers (ATs) in certain settings.

Objective:

To gain insight and understanding into the factors and circumstances affecting female ATs' decisions to persist in or leave the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (NCAA D-I FBS) setting.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

The 12 NCAA D-I FBS institutions within the Southeastern Conference.

Patients or Other Participants:

A total of 23 women who were current full-time ATs (n = 12) or former full-time ATs (n = 11) at Southeastern Conference institutions participated.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Data were collected via in-depth, semistructured interviews, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed via a grounded theory approach. Peer review and member checking methods were performed to establish trustworthiness.

Results:

The decision to persist involved 4 main factors: (1) increased autonomy, (2) increased social support, (3) enjoyment of job/fitting the NCAA D-I mold, and (4) kinship responsibility. Two subfactors of persistence, the NCAA D-I atmosphere and positive athlete dynamics, emerged under the main factor of enjoyment of job/fitting the NCAA D-I mold. The decision to leave included 3 main factors: (1) life balance issues, (2) role conflict and role overload, and (3) kinship responsibility. Two subfactors of leaving, supervisory/coach conflict and decreased autonomy, emerged under the main factor of role conflict and role overload.

Conclusions:

A female AT's decision to persist in or leave the NCAA D-I FBS setting can involve several factors. In order to retain capable ATs long term in the NCAA D-I setting, an individual's attributes and obligations, the setting's cultural issues, and an organization's social support paradigm should be considered.

Keywords: job satisfaction, turnover, qualitative research

Key Points.

Although a certain amount of employee turnover is expected and necessary, high levels of turnover can negatively affect organizations.

A female athletic trainer's decision to persist in or leave the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting can involve a number of factors, including enjoyment of the atmosphere and student-athletes; “fit” with the job; social support and autonomy; responsibility to family members; life balance issues; and role conflict and role overload.

To promote the retention of qualified female athletic trainers in the Division I setting, an individual's attributes, personal obligations, and perceived life balance should be considered in conjunction with the organization's social support structure and cultural issues.

The growing need for health care services versus the decreasing number of health care professionals has been well documented.1 Professionals in several health care fields have experienced low job satisfaction,2 high or conflicting job demands and work overload,3–5 increased stress and burnout,6 and retention/attrition issues.7–9 Since the 1950s, the athletic training profession in particular has experienced increased growth, reform, and recognition. During this evolution, research attention has been focused on certified athletic trainers (ATs) employed in the college/university setting and especially at the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I (NCAA D-I) level in the areas of job satisfaction,10–13 work-family conflict,12–14 stress and burnout,15 and socialization.16,17 These professional issues in the collegiate athletic training setting may reflect the disparity among the cultural expectation to win, ATs' quality of life, and the best practices for athlete health care.16

Female ATs have significantly advanced over the years into what was once a male-dominated profession, constituting 49.5% of the National Athletic Trainers' Association certified membership and 46.5% in the college/university setting in 2008.18 Yet perceived barriers remain for female ATs, including gender equity19,20 and life balance issues,13,21,22 particularly in the NCAA D-I setting. In a recent study14 on work-family conflict in the NCAA D-I setting, a trend toward early departure for female ATs was demonstrated. Female ATs must not only deal with the demands and pressures in the NCAA D-I setting but also with the demands and stereotypes associated with childbearing and cultural issues regarding the “traditional” woman's role in American society (as the primary caregiver to the immediate family and caretaker of the home).23 Facing these challenges and concerns, some female ATs persist at the NCAA D-I setting, whereas others leave. Many female ATs decide to leave for another athletic training setting that better fits their personal or professional needs (or both), and some leave the field altogether. Examining female ATs in this setting via an in-depth, qualitative inquiry may enhance our understanding of their experiences in the NCAA D-I setting.

Researching and explaining voluntary turnover has important implications for organizations and their personnel planning. A certain amount of turnover is inevitable and necessary; however, a large amount of voluntary turnover can adversely influence organizational effectiveness and goal achievement.24 Retention factors and turnover have been heavily investigated in the coaching25,26 and nursing professions.8,9,27 Capel28 was the first to investigate attrition among ATs and found that time commitments, low salary, limited advancement, and administrative and coaching conflicts were related to job dissatisfaction and were the primary reasons for leaving the profession. Overall, few researchers have studied the retention and attrition of ATs, regardless of gender. To date, no researchers have investigated both the current and past experiences of NCAA D-I female ATs and, specifically, the more elaborate, high-profile programs of the NCAA D-I Football Bowl Subdivision (NCAA D-I FBS). Therefore, our purpose was to gain insight and understanding into the factors and circumstances affecting female ATs' decisions to persist in or leave the NCAA D-I FBS setting. The research question guiding this inquiry was as follows: What are the factors, experiences, or circumstances that contribute to female ATs persisting in or leaving the NCAA D-I FBS setting? We believe the development of profiles of ATs persisting in or leaving certain settings is warranted to support continued research in the retention and attrition of ATs, to contribute to the evolution and success of the athletic training profession, and to assist with organizational effectiveness and continuity of patient care.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 23 female ATs with professional experience in the NCAA D-I FBS athletic training setting participated in our study. In order to obtain a representative sample from high-profile NCAA D-I FBS athletics, we attempted to recruit 1 current AT (C-SECAT) and 1 former AT (F-SECAT) from each of the 12 institutions in the Southeastern Conference (SEC) using criterion and snowball sampling methods. Snowball sampling is a technique used to generate a growing sample by relying on referrals from initial or potential participants.29(p318) Potential participants were contacted via e-mail and telephone, and an invitation letter and consent form were e-mailed to each participant. The C-SECATs (n = 12) were full-time employees at SEC institutions, provided full athletic training coverage, traveled with 1 or more sport teams, and had remained at their respective SEC institution for at least 2 years. We attempted to recruit 1 female participant from each SEC institution who voluntarily left the full-time position and the NCAA D-I FBS athletic training setting after at least 1 year of service. However, 1 SEC institution had not, to date, had a full-time female AT leave; therefore, we recruited 1 F-SECAT from each of the remaining 11 SEC institutions. The F-SECATs had either changed settings within the athletic training profession (setting changers) or left the athletic training profession (attritioners).

Research Design

A qualitative inquiry using a grounded theory approach was used to identify relationships, concepts, and categories from the data obtained. In-depth interviewing provides an avenue for understanding a specific setting within the athletic training culture and the possible shared meanings and attitudes of individuals who possess similar social characteristics.17 A causal model of turnover with established reliability and validity served as a theoretical framework for the investigation of NCAA D-I FBS retention and attrition experiences.24,27 The model24 specifies 22 determinants (12 exogenous, 4 endogenous) with a positive or negative and a direct or indirect relationship to voluntary turnover. Our intention was not to superimpose the model on the participants' experiences but to let it guide and inform the preliminary study and the subsequent qualitative inquiry.

We performed a qualitative preliminary study involving 1 in-person focus group with 2 potential C-SECATs and 1 telephone interview with a potential F-SECAT to primarily assist with interview question development. Although the data collected were not included in the overall analysis, this preliminary study provided insight into factors of retention and attrition and potential interest and willingness to participate. Attrition addressed in our study was limited to voluntary leaving; therefore, individuals who involuntarily left the NCAA D-I FBS setting for reasons such as incompetence or legal issues were not included.

Data Collection

After receiving institutional review board approval, we conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews to serve as the primary form of data collection. Based on the preliminary study results, we constructed separate interview guides (Appendix) for each group (C-SECATs, F-SECAT setting changers, and F-SECAT attritioners) to probe their different experiences. The interview began with the participant's desire to become an NCAA D-I FBS AT and then probed the decision to persist in or leave the NCAA D-I FBS setting. All interview guides were pilot tested by the lead investigator, either in person or via telephone, and were deemed appropriate (with minimal changes) in both content and length. No major differences were found between in-person and telephone pilot interviews. The lead investigator (A.G.) subsequently performed all interviews either in person (n = 9) or via telephone (n = 14), based on feasibility.

Data Analysis

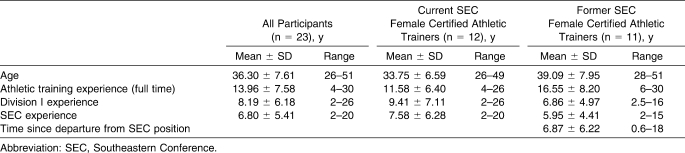

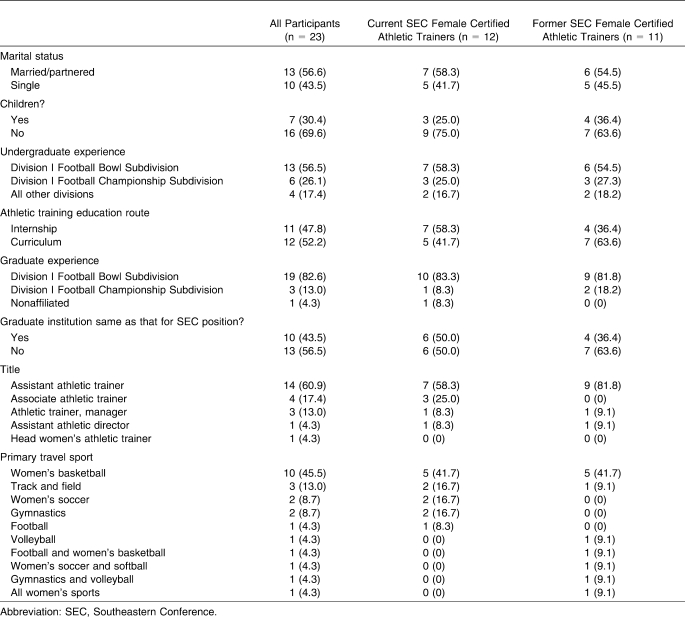

We used SPSS software (version 10.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to determine descriptive statistics (Table 1) and frequency distributions (Table 2) of the participants' demographic data (N = 23). Our goal was to obtain a representative sample with regard to sport coverage, experience, and social status.

Table 1.

Participants' Ages and Experience

Table 2.

Participants' Demographic Data, n (%)

Qualitative research allows the researcher to simultaneously collect and analyze data. This approach assisted in guiding subsequent interviews and allowed for pursuit of emergent themes.30 Pseudonyms were assigned to each participant, and we began verbatim transcription, coding, and analysis immediately after initial data collection. The lead investigator (A.G.) primarily conducted the data analysis.

We used qualitative research software (NVivo version 7; QSR International Inc, Cambridge, MA) to assist in the analysis of the data. Grounded theory is a method of qualitative data analysis that incorporates a systematic set of procedures to develop an inductively resultant theory about a phenomenon that is grounded within the data. This method consists of flexible, analytic strategies and a series of coding that provide researchers with a set of inductive steps allowing for a conceptual understanding of the data,29,30 and this method has been incorporated into recent qualitative athletic training research.16,17 During data collection and analysis, we were also consciously looking for saturation of data, which implies that no new information was obtained from the data or that the researcher was exposed to the same information continuously.31

Establishing Trustworthiness of the Data

Trustworthiness of the data was established using 2 main strategies: member checking and peer review. We performed member checking by sending 5 randomly selected interviewees their transcribed interview data and results via e-mail and asking them to comment on the accuracy of the researcher's transcription and analysis. Peer review was performed by 2 independent individuals with qualitative research experience who reviewed the transcripts and overall data analysis. During qualitative research, the researcher becomes the instrument and is, therefore, charged with examining his or her relationship to the study. The primary researcher (A.G.) closely monitored her personal bias as an individual meeting the F-SECAT criteria. Reflective journaling was used after every interview to monitor potential bias during data collection. Weekly peer debriefing with both affiliated and independent colleagues was used to monitor potential bias during both data collection and analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

Descriptive statistics of the demographic data illustrated that the F-SECATs were slightly older and possessed more overall full-time AT experience (Table 1) than the C-SECATs, who had more NCAA D-I and SEC full-time experience. Frequency distributions revealed very little difference between the groups with regard to marital or partnered status (Table 2). Only 25% (n = 3) of C-SECATs and 36.4% (n = 4) of F-SECATs had children, and only 1 C-SECAT had more than 1 child. The majority of all participants' undergraduate (82.6%, n = 19) and graduate (95.6%, n = 22) educations were obtained at NCAA D-I institutions, and 43.5% (n = 10) had been graduate assistant ATs at the same SEC institution in which they held their full-time position. More C-SECATs (41.6%, n = 5) held associate or managerial positions than F-SECATs (18.2%, n = 2), and no C-SECAT primarily covered and traveled with more than 1 sport team, compared with 36.4% (n = 4) of F-SECATs who covered and traveled with multiple sport teams.

Factors Contributing to Female ATs Persisting in the NCAA D-I FBS Setting

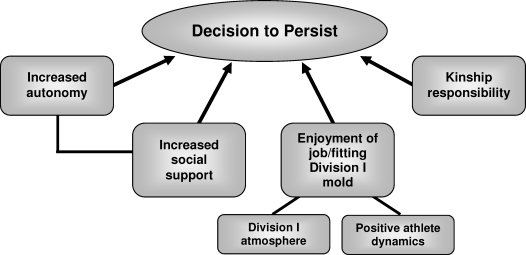

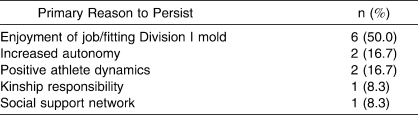

Our grounded theory analysis of C-SECAT participants' experiences revealed 4 main themes and 2 subthemes as factors or circumstances contributing to female ATs persisting in the NCAA D-I FBS setting (Figure 1). The 4 main themes that emerged were (1) increased autonomy, (2) increased social support, (3) enjoyment of the job/fitting the NCAA D-I AT mold, and (4) kinship responsibility. The NCAA D-I atmosphere and positive athlete dynamics also emerged as contributing factors or circumstances; however, they were considered specific characteristics within the main theme of enjoyment of job aspects/fitting the NCAA D-I AT mold. These themes were initially obtained by analyzing responses to the question, “What specific factors have contributed to you[r] staying at the NCAA D-I SEC setting and why?” The primary or top reasons for persisting are presented in Table 3. Responses to other questions that probed job satisfaction, choices, and challenges were cross-checked against responses to this major question. The above themes and corresponding subthemes are discussed in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Factors and circumstances contributing to female athletic trainers persisting in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting.

Table 3.

Current Southeastern Conference Female Certified Athletic Trainers' Primary Reason to Persist in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Setting (n = 12)

Increased Autonomy

The C-SECAT participants spoke about how increased autonomy has influenced their persistence in the NCAA D-I FBS setting. Izzy stated: “I think that what makes me stay is the ability to do my job, the freedom, the autonomy, to be able to get an idea and work … that idea into fruition.” A relationship between increased autonomy and supervisory support (under the main theme of social support) also emerged from the participants' experiences. Hannah elaborated on the importance of

… being able to be given the opportunities to really focus on my needs as a professional; to go to these leadership conferences and learn how to make my staff better, and my head [athletic] trainer giving me the freedom to do that.

Increased autonomy was also described as a factor for choosing the collegiate athletic training setting. Emma noted, “… we have more freedom to practice in the collegiate level … it's just much easier to try things.…”

Increased Social Support

With regard to the NCAA D-I FBS setting, the participants' social support network included a variety of avenues: (1) administrative (athletic department), (2) supervisory, (3) coaches, (4) colleagues (fellow staff, fellow SECATs, and other current or former ATs), (5) non-AT friends, and (6) immediate family. The C-SECATs frequently spoke about the importance of social support, especially athletic training staff support, camaraderie, and a family-like atmosphere. Faye noted that “… the philosophy that we … adhere to is that we're a family. We've got each other's back. We celebrate with weddings. We're sad on deaths and whatever, and we just try to take care of each other.” Lacey elaborated on administrative support by commenting

… we have a fantastic administrator that oversees our department that understands we work hard. She's also very encouraging to us that we take vacations and [get] away from here and she tries to help our coaches understand that if we're here every day of the year and never leave, we're not going to stay for very long.

Participants who were married and especially those who were married with children spoke often about their supportive and understanding spouses. Hannah said, “My husband kind of brings me down to reality a lot … to try and put everything into perspective … because it's a lot on him on those days that I do travel … to take care of the kids.…”

Enjoyment of the Job/Fitting the NCAA D-I AT Mold

Enjoyment and fit as a NCAA D-I AT was the most frequent primary reason C-SECATs gave for persisting. They expressed a sense of familiarity and comfort about choosing this setting for full-time work because the NCAA D-I athletic training setting and atmosphere is “… where I've been, and that's all I know.” Faye, for example, has been at her SEC institution for more than 20 years. She explained:

… I just enjoy it, and I don't know of any other thing that I would do … to use a Christian term, this is what I was made to do, and that's what's kept me doing what I do …. I'm still having fun … So, for me this job is more than just a job, it's kind of a spiritual outlook.…

Participants also spoke frequently about the rewards of returning an injured athlete to full function and participation as one of the most satisfying aspects of their jobs.

The C-SECATs often noted enjoying the competitiveness, celebrity, travel, perks, and resources that attend the NCAA D-I atmosphere. Access to NCAA D-I athletic training–related resources was an important aspect in job performance. Gwen elaborated on the resources and perks of the setting by stating

… I like the competitive nature at this level, not that I think some of the other levels aren't. I like some of the perks that come along … there's crowds, and there's TV, and it's a big deal … it's fun … I just enjoy the all-around atmosphere of it … there's more pressure at this level, but you also have a little bit more to work with.

The C-SECATs spoke at length about their working relationships with the student-athletes. These relationships were overwhelmingly described as an important aspect of job satisfaction. Working specifically with the college-aged student-athlete was a factor mentioned frequently in terms of choosing the NCAA D-I athletic training setting. Izzy discussed an interesting facet to choosing the college-age group: “… I also like to be able to make the decision with the student-athlete and not necessarily have to go through [the parents] all the time … like you would at a high school.…”

Other specific characteristics of the positive athlete dynamics experienced by participants were the relationships, bonds, and parenting role that developed over time. Becky commented: “… I've developed a relationship with these girls … I was the first one they wanted to invite to their graduation.” Participants spoke about the satisfaction of influencing and witnessing the growth and maturity of their student-athletes as well as garnering their gratitude and respect.

Kinship Responsibility

Kinship responsibility was defined by Price24 as the degree or existence of obligations toward family who live within the local community. Two C-SECAT participants stated a primary reason for persisting at their NCAA D-I FBS position was kinship responsibility. However, according to these participants, kinship responsibility could also be a factor in leaving their position or the setting. Darcie stated:

I think the reason I've stayed here is that my husband's been fortunate to have jobs that have allowed him to be near here … should his position change, my position would change … he sacrificed a lot for me to be able to do this, because he knows how much I love it and how much I enjoy it.

Kinship responsibility offered a unique aspect to the participants' persistence in that it may also become a factor in attrition from the setting.

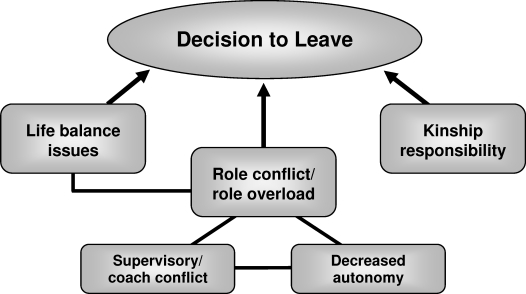

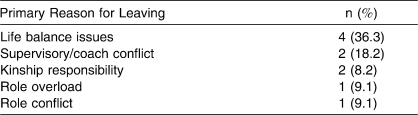

Factors Contributing to Female ATs Leaving the NCAA D-I FBS Setting

Grounded theory analysis of F-SECAT participants' experiences revealed 3 main themes and 2 subthemes as factors or circumstances contributing to female ATs leaving the NCAA D-I FBS setting (Figure 2). We conducted the analysis so that these themes were in the same format as for those persisting in the setting, and the primary or top reason for leaving is presented in Table 4. The 3 main themes that emerged were (1) life balance issues, (2) role conflict and role overload, and (3) kinship responsibility. We considered life balance issues and role conflict and role overload to have an associative relationship. The 2 subthemes we deemed related to each other and the larger theme of role conflict and role overload were entitled (1) supervisory and coach conflict and (2) decreased autonomy.

Figure 2.

Factors and circumstances contributing to female athletic trainers leaving the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting.

Table 4.

Former Southeastern Conference Female Certified Athletic Trainers' Primary Reason for Leaving (n = 11)

Life Balance Issues

Life balance issues primarily involved difficulty prioritizing personal life or family (or both) over the job. The F-SECATs with children spoke primarily to work-family conflict, specifically struggling to manage family demands and desires and job demands. Brooke explained:

… it got to the point where it was like I had raised other people's kids all these years, ‘Is [my daughter] going to have to come second when she's playing soccer or doing whatever she's doing. Am I going to have to miss that to take care of somebody else's kid?’.…

Renee spoke of making difficult decisions regarding life balance and role overload issues even in the midst of administrative and coaching support at her SEC institution:

I had a great opportunity my first year. My first child got to travel with us, and they paid for a babysitter … and I could do that until he was 2 … as he became mobile … I felt it was going to be a bigger disruption … I was working a lot and [it] distract[ed] from my family life, so that was my biggest deciding factor … It's about the quality of life that I want to have, and the quality of life that I want with my family.

Sally elaborated on negative life balance and work-family conflict by saying: “… you're traveling all the time … the amount of hours that you work … I loved it, I miss it, but I also like seeing my family.” Single F-SECATs with no children also spoke of life balance issues. Natalie stated: “I had no life. I couldn't even plan a life in terms of vacation, [holidays] … I gave 3 years of my life to Division I, and it's time for me to have a life.”

Role Conflict and Role Overload

Role conflict involves incompatible or inconsistent expectations.24 One aspect of role conflict was the effect of NCAA D-I bureaucracy and pressure to win on ATs' jobs. Marie elaborated on how the effect of NCAA D-I bureaucracy often took her away from practicing athletic training by describing

… it wasn't about the nuts and bolts of athletic training … That was … one of the reasons why I just hit my breaking point, because it was meetings to have meetings … I wanted to go to practice to watch how someone's knee was holding up ….

Brooke commented on the NCAA D-I perspective:

… and the things that we worried about that were so dramatic … ‘Were the green beans crisp enough … Why didn't you have freezy pops after practice?’… somehow if they could bring some perspective … back into it.

Natalie noted the effect of not having an off-season on student-athletes: “… I don't believe in year-round training. I believe we need to go back to having a true off-season … [The athletes] never get a chance to heal.…”

The F-SECATs' reflections on role conflict were also associated with the subtheme of supervisory and coach conflict. Vicky expanded on the aspect of role conflict:

I felt like the coaching staff put themselves against the athletic training staff quite a bit … instead of just coaching, they're telling you how to do your job and that sort of thing … There was one [instance] where I was like, ‘You and I disagree on this, but my job is to intervene in the best interest of the athlete.’

The subtheme of supervisory and coach conflict and its relation to overall role conflict is discussed further in the following section.

Role overload is concerned with role expectations exceeding available time and resources.24 The F-SECATs spoke less about available resources and more about increased time constraints and travel demands of the NCAA D-I FBS setting and how these job aspects affected their attempts at life balance. Taylor described role overload by saying: “… it was the time constraints, and the on-call 24 hours a day, and all the traveling … then practicing 10 months, even summer hours. That's where it ended up being too much.” Zoe discussed the feeling of losing herself as a result of the job stress, role overload, negative life balance, and supervisory support issues:

… the biggest thing was I felt like, it was the amount of stress that I was under … I was not the kind of person I wanted to be anymore in that setting … And for my job to make me do that, it wasn't worth it … the overwhelming feeling and fatigue … never being able to do enough … for my athletes, never [being] able to please my boss, ever … the fatigue was just the time that we were made to put in … I couldn't stay on top of things in my personal life.

A subtheme emerging from the F-SECATs' experiences that was deemed to be embedded in role conflict was supervisor and coach conflicts related to inconsistent or incompatible (or both) expectations. Zoe discussed the issue of supervisory and coaching support dynamics:

… I felt a lot [of] times very much caught in the middle between my head [athletic] trainer [and my coach] … I felt like there were things that were done in terms of my team that probably wouldn't have been handled the same way if it was another team, and my coaches saw that … [I was] just trying to keep everybody happy … just trying to keep things as smooth as possible between my boss and then my head coach, and at the same time give the best care possible to my athletes … There was very little supervisor support or administrative support that I saw. I always felt like I was having to fight for everything I got.…

Participants spoke specifically to role conflict when describing difficult working relationships, unrealistic expectations, and an overall lack of respect and appreciation from coaches. Paige spoke of her difficult working relationship with an SEC coach and his unrealistic expectations:

… When I had a coach day in and day out question my education, my judgment, ‘You don't know what you're talking about. [I've] never had a trainer tell me that before …’ I think I had gotten to a point where I was so unhappy working with that coach that I almost considered getting out of the profession entirely.

The second subtheme, decreased autonomy, contributed to role conflict and role overload and was associated with supervisory and coach conflict. Marie explained: “I think that was the biggest frustration that you're on everyone else's clock … You're never consulted … never asked, [and] … never considered.” Taylor, who was married with children, stated:

I think that was probably one of the hardest tasks. I could set up my schedule for my kids and for my family, but then when the athletes or the coaches would change the schedule, that's when it became hard.…

Alex commented on role conflict and how decreased autonomy affected how she performed her athletic training duties by saying: “[I wanted] to do more with rehab and preventive [measures] … [not] just sitting, watching, and waiting for something to happen … not that I didn't enjoy the games, but I'd rather be active.”

Kinship Responsibility

Responsibility to immediate family appeared to influence the initial choice of a SECAT position (to be close to family) but primarily influenced F-SECATs' decisions to leave the setting. Sally gave her main reason for leaving as “[I was] getting married and my husband was in graduate school somewhere in [another state], and he wouldn't be leaving.” Zoe noted that one of the satisfying aspects of her current position was related to kinship responsibility: “… I'm geographically closer to home, closer to my family. That makes a big difference just to be able to … see them and do what I can for them.”

Comparable Participant Experiences, Future Plans, and Advice

The C-SECATs and F-SECATs reported similar experiences in certain areas. For instance, when participants were asked what they would change about NCAA D-I FBS athletics, the overwhelming response was to address bureaucratic issues and the lack of a true off-season. Although life balance issues were major attrition factors for F-SECATs, striving to maintain life balance was also a matter of concern for C-SECATs, one that they overwhelmingly considered their greatest challenge in their current positions. Both C-SECATs and F-SECATs stated that they made personal sacrifices at the NCAA D-I FBS level. Most C-SECATs, however, spoke of certain aspects of their jobs that helped them negotiate challenges and enhance life balance, including increased social support, promotional chances, a change in job duties to decrease travel and time constraints, and setting boundaries. Although F-SECATs spoke often of their reluctance to leave the NCAA D-I FBS setting, their athletes, and their colleagues, they overwhelmingly spoke of improved life balance and social support in their current career positions and a positive change in mood.

When asked about their future plans, 8 of 12 C-SECATs stated that they planned to remain at the NCAA D-I FBS setting and that their personal plans, including starting a family, would not alter their career aspirations at that time. Only 1 of 11 F-SECATs would consider returning to the setting. Advice for young ATs aspiring to work in the NCAA D-I setting included researching and knowing the job expectations and requirements (eg, long hours, hard work, sacrifices), distinguishing your personal goals, and finding a mentor.

DISCUSSION

Retention factors for female ATs in the NCAA D-I FBS setting included enjoyment of the atmosphere and student-athletes, their suitability as NCAA D-I ATs, increased social support and autonomy, and a responsibility to local family members. Attrition factors included a sense of responsibility to nonlocal family, life balance issues, and role conflict and role overload, primarily stemming from supervisor or coach conflict and decreased autonomy.

Fit, Satisfaction, and Retention

Fifty percent of C-SECATs reported their primary reason for persisting in the NCAA D-I FBS setting was that they thoroughly enjoyed their job and just seemed to “fit the NCAA D-I AT mold.” This fit has been described in other studies.32,33 The familiarity and comfort levels C-SECATs experienced that appeared to enhance their enjoyment and fit were likely influenced by their undergraduate (83.3%) and graduate (91.6%) experiences obtained solely from NCAA D-I institutions. Furthermore, 50% of C-SECATs had been graduate assistant ATs at the same SEC institution in which they were currently employed full time. This phenomenon relates to Turner's34 research on sponsored mobility, by which individuals are chosen for a position via established relationships. Prior NCAA D-I experience and increased levels of familiarity and comfort may have influenced clarity and fit and, therefore, may have enhanced ATs' satisfaction and success in their positions. The C-SECATs did not generally speak of role ambiguity, and these results are in contrast to the findings of Pitney et al,17 whose qualitative inquiry on the professional socialization of NCAA D-I ATs revealed a theme of uncertainty and adjustment upon entering the full-time NCAA D-I setting contributing to role ambiguity.

The C-SECATs tended to identify with the high-profile, competitive, and resourceful atmosphere of the NCAA D-I FBS. This enjoyment feature is understandable, considering that these factors have been reasons for both ATs17 and coaches26 aspiring or choosing to work in this setting. Another aspect of job satisfaction and fulfillment experienced by both C-SECATs and F-SECATs in our study was the positive dynamics and bonds developed with student-athletes. Other recent authors have reported similar results on the socialization,16,17 development,32 and organizational commitment33 of NCAA D-I ATs.

The Social Support Paradigm and Retention

Based on our results, we propose that the social support paradigm, including the network of administrative, supervisory, colleague, coach, and kinship support, plays a vital role in both the retention and attrition of female ATs in the NCAA D-I FBS setting. Increased social support on many levels was a major theme of retention in our study.

Organizational Support

Administrative and supervisory support can play a critical role in retaining qualified, long-term employees and in their overall success.16,25 Our findings support those of previous researchers who examined the importance of organizational social support in health care organizations. Price24 and Price and Mueller26 performed extended research on a causal model of turnover and noted that the amount of administrative and supervisory support within an organization can heavily influence overall job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intent to stay. Balogun et al6 proposed that supervisory and colleague support were critical factors in minimizing stress in physical and occupational therapists. Acorn4 reported that increased organizational support can have a buffering effect on role conflict in nurses. The socialization research on NCAA D-I ATs of Pitney and colleagues17(p67) indicated that role stability occurred when “the values of the AT were relatively congruent with the organization's, and fair levels of collegiality and administrative support existed.” Organizational support can also influence ATs' salaries. Pay has received increased interest within the profession35 and has been a factor in AT attrition28 and an issue of concern for female ATs.19,20 However, even though our participants discussed pay, it was not a primary factor involved in their retention or attrition in the NCAA D-I FBS setting.

A perceived lack of organizational support, specifically stemming from supervisor (primarily head AT) and coach conflict, was a subtheme of role conflict and role overload that ultimately contributed to the attrition of some F-SECATs in our study. Other authors have examined the negative effects of organizational support and found similar results. Bousfield36 examined the experiences of clinical nurse specialists and concluded that a lack of organizational support was a deterrent to successfully completing the participants' roles. Pitney16 found coaching issues to be one of the greatest challenges of NCAA D-I ATs, and low levels of administrative support were commonly cited as threatening their quality of life.

Autonomy and Organizational Support

The amount of autonomy experienced by the participants in our study influenced both retention and attrition. The retention theme of increased autonomy was heavily associated with increased administrative and supervisory support, whereas the attrition subtheme of decreased autonomy was influenced by supervisory and coach conflict. Nursing research8,24,27 has revealed strong correlations between organization and leadership structure, autonomy, job satisfaction, and quality of care. In the NCAA D-I athletic training realm, Mazerolle et al14 reported that inflexible work schedules contributed to work-family conflict, and Pitney16 and Pitney et al17 found that autonomy influenced AT role stability and value.

Professional Advancement and Organizational Support

Increased promotional chances have positive effects on both job satisfaction and organizational commitment,24 whereas limited promotional chances have been attrition factors for ATs28 and physiotherapists.7 Professional advancement has been limited or perceived as limited in the athletic training profession, especially in the collegiate setting and especially for women.19,20 Our study demonstrated that C-SECATs (41.6%) held more associative or managerial positions than F-SECATs (18.2%). The organizational support and autonomy garnered from the opportunities to advance in their organization or change job duties to better fit their professional and personal needs appeared to heavily influence retention of female NCAA D-I ATs.

Colleague and Family Support

Colleague, spouse, and family support was also an important facet of the social support paradigm that positively influenced retention in our study. Many C-SECATs spoke of a “family-like,” highly supportive athletic training staff that worked well together, assisted when challenges arose, and respected each other's duties. Our results agree with those of Inglis et al,25 who found that colleagues' understanding, recognition of contributions, and overall support were key factors in the retention of coaches. With regard to female NCAA D-I ATs, our findings also agree with those of Rice et al,22 who noted that coworkers' support contributed positively to life balance and that spousal support was key in their strategies to managing family and career demands. However, Price24 stated that spouses and family members are not only an aspect of support but often an aspect of responsibility or obligation. Our study supported this observation, because kinship responsibility emerged as a decisive factor in both retention in and attrition from the NCAA D-I FBS setting.

Life Balance Struggles and Attrition

The pressure to win and competitiveness of collegiate athletic culture can challenge life balance efforts, and the NCAA has made recent efforts to examine this issue. A 2006 survey37 of more than 4000 NCAA athletic staff to investigate life and work balance revealed that 57% were considering leaving athletics and 35% believed negative consequences would occur if they left work temporarily for personal or family issues. Life balance issues have been extensively studied12–14,16,22,28 and addressed20,21,23 in the athletic training profession, with female ATs often the focal point. We demonstrated that struggling to maintain life balance was a major attrition factor for F-SECATs and was also an issue of concern for several C-SECATs. Single F-SECATs with no children struggled with personal time, whereas married or partnered F-SECATs with or without children primarily experienced work-family conflict. These issues were predominantly associated with aspects of role overload, such as increased time constraints and travel. Mazerolle et al14 found similar results in a mixed-methods study of male and female NCAA D-I ATs, for whom long work hours and travel directly contributed to work-family conflict. The authors also noted that sex and marital or family status had no effect on work-family conflict. Mazerolle et al12 also demonstrated that the work-family conflicts of NCAA D-I ATs (male and female) were negatively correlated with job satisfaction and positively correlated with burnout and intent to leave the profession. Pitney16 showed that NCAA D-I ATs were concerned about high levels of work volume and subsequent diminished quality of life. Similar results have been reported in the coaching profession; Pastore26 found that the major reason NCAA D-I coaches (male and female) left was because of decreased time with family and friends. Inglis et al25 demonstrated that job satisfaction and retention factors in coaching and athletic management included an appropriate balance between work and life conditions.

ATs' Role Conflict, Role Overload, and Attrition

The F-SECATs and some C-SECATs experienced role conflict or role overload (or both) in several ways. Previously discussed aspects include role conflict with supervisors and coaches. Another aspect, which has been supported by a recent study,16 involved dealing with the effects of the NCAA D-I culture and bureaucracy, including the pressure to win and to keep athletes healthy as well as a gradual erosion of the traditional off-season. The NCAA's rules and policies on student-athlete participation and preparation have evolved over the years to include longer in-seasons, longer nontraditional seasons, voluntary workouts (eg, captain's practices), and an emphasis on year-round conditioning.37 This evolution affected our participants in several ways. To begin with, role conflict is experienced when student-athletes rarely have adequate time to heal and fully recover from injuries, a situation incompatible with the duties of an AT. Second, role overload can occur with the erosion of the traditional off-season, which used to be a period of valuable time for catching up and rebalancing life demands. The concomitant increase in coverage now required by ATs to adequately care for their athletes places undue stress on both the individual and the athletic training staff as a whole. Increased coverage, coverage of multiple sports, and lack of adequate AT staffing have been associated with work-family conflict in NCAA D-I ATs.14 Our study also supports the trend of conflicts from coverage of multiple sports: 36.4% of F-SECATs covered and traveled with multiple sport teams, whereas C-SECATs only covered and traveled with a single sport team.

Our results generally agree with those of others who have researched aspects of job stress, including role conflict, overload, ambiguity, strain, and complexity in health care professions. Several studies3,4,8,9,27 in nursing have demonstrated that role conflict, ambiguity, and overload have adverse effects on job satisfaction and are determinants in the intent to leave the profession. Campo et al5 found that physical therapists with high levels of role strain were at increased risk of job turnover and work-related musculoskeletal issues. In the athletic training profession, Brumels and Beach38 noted that most collegiate ATs experienced low levels of role complexity and were relatively satisfied. However, the authors also demonstrated moderately strong correlations among role complexity, job satisfaction, and intent to leave the profession. In other words, as stress levels increased from role complexity, job satisfaction decreased and intent to leave increased. Henning and Weidner39 examined role strain in collegiate ATs who were also Approved Clinical Instructors and found that 49% experienced moderate to high levels of role strain, with role overload being the greatest contributor.

Implications and Proposed Avenues to Increase Retention

The implications of our study relate directly to full-time female ATs within the SEC; however, certain aspects of our findings can be applied to other athletic training settings as well. These results, along with those of previously mentioned studies, could assist the National Athletic Trainers' Association, the NCAA and affiliated institutions, and other organizations in the development of retention programs to educate individuals and organizations on addressing life balance, role conflict, and role overload issues. We agree with the findings from the NCAA's Task Force on Life and Work Balance in Intercollegiate Athletics,37 which recognized that the continued growth, success, and spirit of the NCAA rested on developing an environment that focuses on the people that make it a success and that life balance efforts are not the sole responsibility of the individual but an integration of institutional and individual efforts. The task force's recommendations to develop legislative changes that facilitate improved life balance, such as adjusting countable athletics activities and establishing a nonathletic day for all staff members, may combat the effects of the lack of a true off-season.

Research8 on turnover in nursing indicates that although increasing recruitment and improved compensation may help to offset shortages in the short term, administrative interventions to improve quality of work life are more effective in reducing turnover in the long term. Although more study in this area is warranted, this concept is likely transferrable to athletic training. We also agree with previous authors16,17,39 who have suggested that organizations implement conflict resolution and stress management training, mentoring programs, and better professional socialization practices to help improve overall job satisfaction and quality of life for ATs. Cultivating good relationships to help reduce role conflict with coaches, including adequate respect and appreciation of the service, duties, and lives of both parties, should be considered an important aspect of social support, autonomy, and overall retention. Role overload can be influenced by administrators hiring an adequate number of ATs to provide appropriate care to student-athletes in the midst of increasing coverage demands.

Administrators and athletic training supervisors at individual institutions should evaluate their athletic training divisions to assess the social support paradigm and organizational structure to ascertain if the needs of staff members are being met with regard to professional and personal development.

Limitations

The most significant limitation of our study is its lack of generalizability to other athletic training populations. In qualitative research, however, it is up to the reader to determine how the information provided may be of benefit; therefore, the results of our study may be transferable to other similar contexts. Another limitation is that we only presented a view of retention and attrition or turnover from the AT's perspective. A certain amount of turnover is detrimental to organizational effectiveness and continuity of patient care. The views of other key members of administration involved in the hiring of NCAA D-I FBS ATs, such as athletic directors, were not addressed in this study, and their views and philosophies on retention and attrition may differ from those of the ATs.

Avenues for Future Research

Future researchers focusing on the retention and attrition of ATs should study current and former male NCAA D-I FBS ATs to compare their experiences. Other NCAA D-I conferences, other NCAA divisions, and other athletic training settings should also be explored to obtain a more informative overall view of retention and attrition in the athletic training profession. Quantitative research on the causal model of turnover has been performed in certain health care fields,24 and our findings support the likelihood that multiple avenues lead to turnover or attrition. However, additional investigation of how this model further relates to the athletic training profession is warranted. Furthermore, case studies on institutions and positions with exceptionally high or low attrition and organizations with certain successful policies in place (eg, available child care while traveling) will help us to better understand retention and attrition in certain settings.

Conclusions from our study rest upon the AT's perspective; therefore, future researchers should also focus on obtaining the perspectives of other key individuals associated with the retention and attrition of ATs, such as administrators involved in the hiring and supervision of ATs and coaches. Their philosophies, experiences, and views are important to more fully understand and enhance organizational structure and program effectiveness.

Conclusions

Although a certain amount of turnover is expected and necessary, high turnover can negatively affect organizations.24 A female AT's decision to persist in or leave the NCAA D-I FBS setting can involve several factors. Individual attributes, personal obligations, and perceived life balance, as well as an organization's social support paradigm and cultural issues, should be considered to better understand the retention of quality, long-term employees who can continue to positively influence the athletic training profession.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to all of the athletic trainers who agreed to participate in this study and who took the time to share their experiences.

Appendix. Condensed Semistructured Interview Guides

General questions asked of all participants:

Why did you choose the athletic training profession, and what brought you to be an ATC at the collegiate level?

Why did you choose the NCAA DI athletic training setting? Why the SEC?

What were your expectations as you entered into the NCAA DI and SEC? Were these expectations met?

Do you feel your athletic training education and experiences prior to working full-time at the NCAA DI/SEC setting prepared you for your job?

Describe your first few years as an NCAA DI/SEC ATC.

Describe how your role has evolved or changed in your current position over the years. Tell me about the ATC/professional you were then compared to the ATC/professional you are now.

Describe your support networks inside and outside of athletic training/profession. Supervisor/administrative?

Is there anything you would change about NCAA DI athletics or the athletic training setting?

What are your future career plans? Do you plan to remain at this level/setting/career? Personal/family plans?

What advice would you give to a young, newly certified female ATC aspiring to work at the NCAA DI/SEC athletic training setting?

Questions asked of current SEC athletic trainers:

What are the good or satisfying things about your current SEC position?

What specifically keeps you coming back every day? What drives you?

What do you feel is, or has been, your greatest challenge in your current position?

Is there anything you do not like or find least satisfying about your job?

What are the possible obstacles/challenges you come across and how do you negotiate or overcome them?

Do you feel you have made sacrifices personally or professionally to remain at this level?

How do you manage your personal time/obligations? (Probe based on marital status, children)

What specific factors have contributed to you staying at the NCAA DI/SEC setting and why? What makes you stay? Can you prioritize or rank these factors in order of importance?

Do you feel your career and/or personal plans would allow you to stay at the NCAA DI/SEC setting?

Questions asked of former SEC athletic trainers:

Were there things you liked and enjoyed about the NCAA DI and SEC setting?

What were your greatest challenges you came across during your tenure?

Why did you leave the NCAA DI/SEC setting? What factors or circumstances contributed to your decision to leaving? Can you prioritize or rank the top reasons why you left?

Can you point to a specific time or threshold where you said “I'm done, I need to go”? Explain this time period.

What would it have taken for you to stay at the NCAA DI/SEC setting?

Do you miss anything about the NCAA DI or SEC setting?

Compare NCAA DI/SEC support networks to those in your current position.

(Setting changers) Why did you choose to stay in athletic training by changing settings?

(Attritioners) Why did you choose to leave the athletic training profession?

What do you like or is most satisfying about your current athletic training setting or career choice? What drew you to this position?

Tell me about the person you were as a NCAA DI/SEC ATC compared to the person you are now.

Do you feel you made sacrifices personally and professionally while at the NCAA DI/SEC level? How about in your current position? If so, compare those sacrifices.

How do you now manage your personal time/obligations? (Probe based on marital status, children, etc) Is this different from your tenure as a NCAA DI/SEC ATC?

Abbreviations: ATC, athletic trainer; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; DI, Division I; SEC, Southeastern Conference.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones W. J., Johnson J. A., Beasley L. W., Johnson J. P. Allied health workforce shortages: the systematic barriers to response. J Allied Health. 1996;25(3):219–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broski D. C., Cook S. The job satisfaction of allied health professionals. J Allied Health. 1978;7(4):281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert V. A., Lambert C. E. Literature review of role stress/strain on nurses: an international perspective. Nurs Health Sci. 2001;3(3):161–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acorn S. Relationship of role conflict and role ambiguity to selected job dimensions among joint appointees. J Prof Nurs. 1991;7(4):221–227. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(91)90031-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo M. A., Weiser S., Koenig K. L. Job strain in physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):946–956. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balogun J. A., Titiloye V., Balogun A., Oyeyemi A., Katz J. Prevalence and determinants of burnout among physical and occupational therapists. J Allied Health. 2002;31(3):131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noh S., Beggs C. E. Job turnover and regional attrition among physiotherapists in northern Ontario. Physiother Can. 1993;45(4):239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes L. J., O'Brien-Pallas L., Duffield C., et al. Nurse turnover: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):237–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coomber B., Barriball K. L. Impact of job satisfaction components on intent to leave and turnover for hospital-based nurses: a review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(2):297–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett J. J., Gillentine A., Lamberth J., Daughtrey C. L. Job satisfaction of NATABOC certified athletic trainers at Division One National Collegiate Athletic Association institutions in the Southeastern Conference. Int Sports J. 2002;4(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrera R., Lim J. Y. Job satisfaction among athletic trainers in NCAA Division IAA institutions. http://www.thesportjournal.org/2003journal/vol6-no1/satisfaction.asp. Accessed July 2, 2007.

- 12.Mazerolle S. M., Bruening J. E., Casa D. J., Burton L. J. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milazzo S. A., Miller T. W., Bruening J. E., Faghri P. D. A survey of Division I-A athletic trainers on bidirectional work-family conflict and its relation to job satisfaction [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):S-73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazerolle S. M., Bruening J. E., Casa D. J. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):505–512. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendrix A. E., Acevedo E. O., Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35(2):139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitney W. A. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitney W. A., Ilsley P., Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Athletic Trainers' Association. Certified membership. http://www.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/2008EOY-stats.htm. Accessed July 15, 2009.

- 19.Booth C. L. Certified Athletic Trainers' Perceptions of Gender Equity and Barriers to Advancement in Selected Practice Settings [dissertation] Grand Forks: University of North Dakota; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez P. S., Hibbler D. K., Cleary M. A., Eberman L. E. Gender equity in athletic training. Athl Ther Today. 2006;11(2):66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nussbaum E., Rogers M. J. Athletic training and motherhood: exclusive or compatible endeavors. NATA News. November 2000. pp. 12–13.

- 22.Rice L., Gilbert W., Bloom G. Strategies used by Division I female athletic trainers to balance family and career demands. J Athl Train. 2001;36(suppl 2):S-73. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camilone L., Delmont G. WATC targets life balancing. NATA News. April 2004. p. 46.

- 24.Price J. L. Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. Int J Manpower. 2001;22(7):600–624. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inglis S., Danylchuk K. E., Pastore D. L. Understanding retention factors in coaching and athletic management positions. J Sport Manag. 1996;10(3):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastore D. L. Male and female coaches of women's athletic teams: reasons for entering and leaving the profession. J Sport Manag. 1991;5(2):128–143. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price J. L., Mueller C. W. A causal model of turnover for nurses. Acad Manag J. 1981;24(3):543–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capel S. A. Attrition of athletic trainers. Athl Train J Natl Athl Train Assoc. 1990;25(1):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss A., Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charmaz K. Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In: Denzin N., Lincoln Y., editors. Handbook of Interview Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. pp. 675–694. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitney W. A., Parker J. Qualitative research applications in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2002;37(suppl 4):S168–S173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malasarn R., Bloom G. A., Crumpton R. The development of expert male National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winterstein A. P. Organizational commitment among intercollegiate head athletic trainers: examining our work environment. J Athl Train. 1998;33(1):54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner R. H. Sponsored and contest mobility and the school system. Am Sociol Rev. 1960;25(6):855–867. [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Athletic Trainers' Association. New salary survey shows increased pay in most settings. NATA News. June 2005. pp. 22–23.

- 36.Bousfield C. A. A phenomenological investigation into the role of the clinical nurse specialist. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25(2):245–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NCAA. NCAA life and work balance task force executive summary. http://www.ncaa.org/wps/ncaa?key=/ncaa/NCAA/Academics+and+Athletes/Personal+Welfare/Life+and+Work+Balance. Accessed August 20, 2009.

- 38.Brumels K., Beach A. Professional role complexity and job satisfaction of collegiate certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43(4):373–378. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henning J. M., Weidner T. G. Role strain in collegiate athletic training Approved Clinical Instructors. J Athl Train. 2008;43(3):275–283. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]