Abstract

Following peripheral nerve injury, Schwann cells (SCs) vigorously divide to survive and produce a sufficient number of cells to accompany regenerating axons. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have emerged as modulators of SC signaling and mitosis. Using a 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay, we previously found that a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor (MMPi), GM6001 (or Ilomastat), enhanced division of cultured primary SCs. Here, we tested the hypothesis that the ability of MMPi to stimulate SC mitosis may advance nerve regeneration in vivo. GM6001 administration immediately after rat sciatic nerve crush and daily thereafter produced increased nerve regeneration as determined by nerve pinch test and growth-associated protein-43 (GAP-43) expression. MMPi promoted endoneurial BrdU incorporation relative to vehicle control. The dividing cells were mainly SCs and were associated with GAP-43-positive regenerating axons. After MMP inhibition, myelin basic protein mRNA expression (determined by Taqman RT-qPCR) and active mitosis of myelin-forming SCs were reduced, indicating that MMPs suppressed their de-differentiation preceding mitosis. Intra-sciatic injection of the inhibitor of SC mitosis mitomycin suppressed nerve regrowth is reversed by MMPi, suggesting that its effect on axonal growth promotion depends on its pro-mitogenic action in SCs. These studies establish novel roles for MMPs in peripheral nerve repair via control of SC mitosis, differentiation and myelin protein mRNA expression.

Keywords: Axonal regeneration, Matrix metalloproteinases, Myelin, Myelin basic protein, Nerve growth, Schwann cell

INTRODUCTION

When damaged peripheral nerve fibers undergo Wallerian degeneration (WD) (i.e. axonal degeneration, myelin breakdown and removal, facilitated by infiltrating macrophages distal to the site of injury [1]), they leave behind de-differentiating Schwann cells (SCs) inside basal lamina tubes that can re-enter the cell cycle (2). SC proliferation ensures the formation and survival of sufficient SC numbers to support axonal regeneration (3). The fate of post-mitotic SCs is determined by the phenotype of axons with which they associate during the process of radial sorting (4); myelin-forming Schwann cells (mSC) pair with axons designated to myelinate at a 1:1 ratio, whereas non-myelin-forming Schwann cells (nmSC) support multiple unmyelinated axons, (up to 10 in humans). Continuous and dynamic axonal-SC signaling interactions are involved in molecular regulation of SC mitoses, which are induced in WD through the action of macrophage-released mitogens (5) and myelin degradation products (3, 6).

The onset of axonal growth manifests within hours of peripheral nerve injury as regenerating sprouts grow down the endoneurial tubes (2). Axon growth cones interface closely with the SC membrane and basal lamina on either side, providing both an adhesive substratum and a plethora of molecular guidance cues (4). The success of nerve regeneration after rat sciatic nerve crush injury is due in part to preserved integrity of SC basal lamina and endoneurial tubes (2). Because sciatic nerve crush injury is characterized by a 30-hour lag before the axons enter the degenerating distal stump (2, 7), identifying modulators of WD, SCs and their basal lamina function during this lag period may lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies for stimulating nerve regeneration in this critical early period. In a model of nerve regeneration that occurs independent of WD, SCs initiate axonal guidance in part by deposition of laminin, a growth-promoting component of SC basal lamina (8) and a substrate of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (9).

MMPs are members of an extracellular protease family of collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins and membrane-type MMPs (9) that have emerged as early modulators of WD, SC function and SC basal lamina remodeling (10–13). MMP-9 (gelatinase B) is among the earliest MMPs to respond to peripheral nerve damage; it is expressed in SCs within 1 hour and peaks at 24 hours after injury and promotes axonal degeneration, macrophage infiltration and myelin degradation in damaged nerves (14–17). We have recently reported that robust MMP-9 induction within 24 hours occurs in both degenerating (distal) and regenerating (proximal) nerve segments of axotomized sciatic nerves (15), suggesting a potential role for MMP-9 in the early events of peripheral nerve regeneration. Proximal stumps of axotomized nerves of MMP-9 knockout mice display an increase in 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in SCs, indicating that MMP-9 suppresses SC mitosis during nerve regeneration (15). In primary cultured SCs, MMP-9 inhibits mitosis via ErbB-mediated activation of the extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) MAPK pathway. Furthermore, treatment with the MMP inhibitor (MMPi) GM6001 reverses the effect of MMP-9 and further promotes SC proliferation (15). While GM6001 treatment stimulates DRG neurite outgrowth in vitro (18), the effects of MMPi therapy on SC mitosis or nerve regeneration in vivo are unidentified.

The present study determined the effects of MMPi treatment initiated immediately after rat sciatic nerve crush injury. Overall, the data indicated that MMPs are potent modulators of SC proliferation, differentiation and myelin protein expression after peripheral nerve injury and therefore are potential therapeutic targets in the early post-injury period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Surgeries

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (200–225 g, n = 102) were obtained from Harlan Labs (San Diego, CA). Animals were housed at 22°C under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Anesthesia was achieved using 4% Isofluorane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) in 55% oxygen by inhalation, or rodent anesthesia cocktail of Nembutal (50 mg/ml; Abbott Labs, North Chicago, IL), Diazepam (5 mg/ml, Steris Labs, Phoenix, AZ) and saline (0.9%, Steris Labs) by i.p. injection. Sciatic nerves were exposed unilaterally at the mid-thigh level and crushed using fine forceps twice for 5 seconds each. Animals were killed using an overdose of injection of rodent anesthesia cocktail (specified above) i.p., followed by lethal intracardiac injection of Euthasol (Virbac, Fort Worth, TX, 100–150 mg/kg). Nerve sections proximal and distal to crush were collected for analysis. Sham operations included unilateral sciatic nerve exposure. All procedures were performed according to NIH Guidelines for Animal Use and protocols approved by the San Diego VA Healthcare System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

MMP Inhibitor and Mitomycin Treatments

The broad-spectrum MMPi GM6001 (Ilomastat, or N-[(2R)-2-(hydroxamido carbonylmethyl)-4-methylpentanoyl]-L-tryptophan methylamide, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) has a reported Ki of 0.4 nM for MMP-1, 27 nM for MMP-3, 0.5 nM for MMP-2, 0.1 nM for MMP-8, and 0.2 nM for MMP-9. GM6001 or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide in ethanol) were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and administered at 10 mg/kg/day by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, as shown effective in other models of neuronal damage (14, 19–22). MMPi and vehicle were administered immediately after sham or nerve crush surgery and once daily for 5 days thereafter. Mitomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, at 10 µg in 6 µl of Ringer’s solution (Sigma)) was administered by intra-sciatic injection using a 33-gauge needle once immediately prior to nerve crush surgery to inhibit endoneurial cell mitosis (23–25).

Nerve Pinch Test

The rate of axonal regeneration was evaluated using nerve pinch test (7, 26–28), as illustrated in Figure 1A. Based on the anticipated speed of sciatic nerve regrowth, the test was performed between 3 and 7 days after nerve crush (7), although it can be successful as early as 2 days after crush (26). The sciatic nerve and its tibial nerve branch were exposed in lightly anesthetized rats. Consecutive 1-mm-long segments of the tibial nerve were pinched with a pair of fine forceps, starting from the distal end of the nerve and proceeding in the proximal direction until a reflex response consisting of a contraction of the muscles of the back was observed. The distance between the most distal point of the nerve that produced a reflex withdrawal response and the stitch marking the original crush site was measured under a dissecting microscope and identified as the regeneration distance. The test was performed by an experimenter blinded to the experimental groups of 4 to 6 per group. Animals were killed as described above and sciatic nerves were isolated for Western blotting.

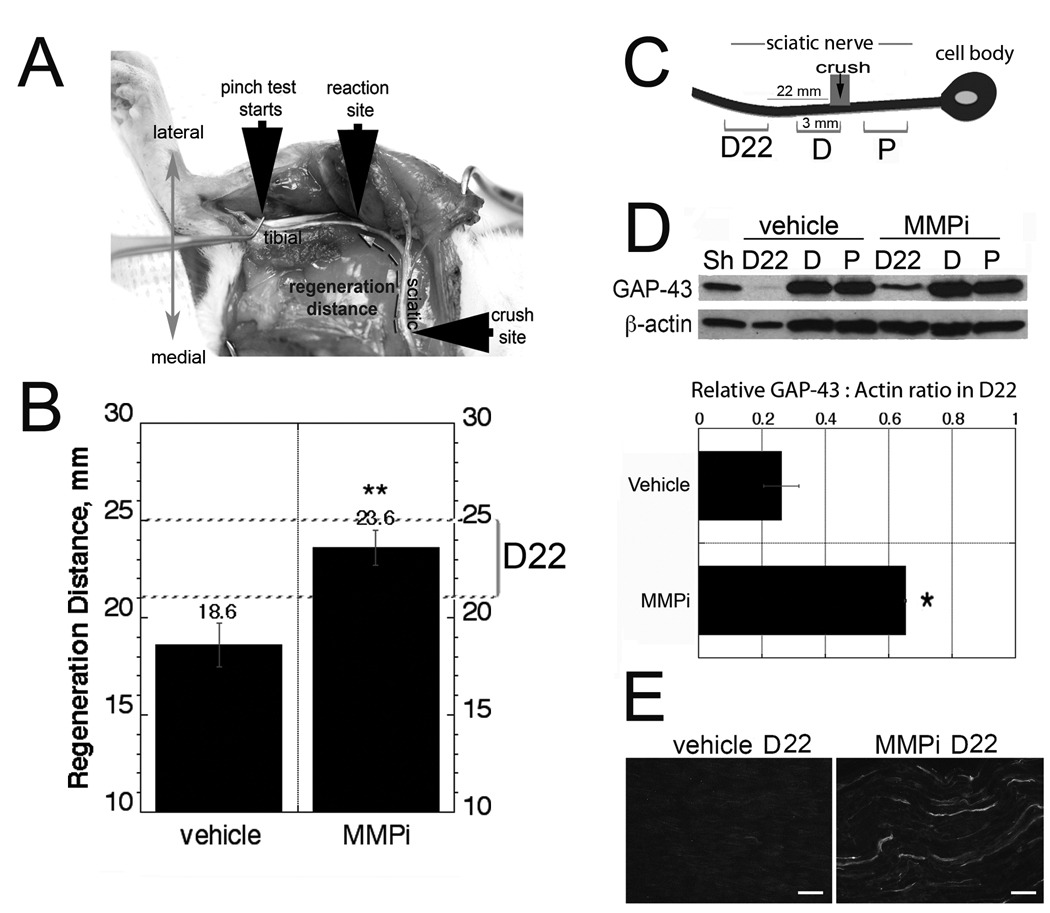

Figure 1.

Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (MMPi) GM6001 treatment promotes peripheral nerve regeneration. (A) Nerve pinch test in a rat viewed from the dorsal plane. The exposed sciatic nerve and its tibial branch are pinched with forceps in 1-mm-long consecutive segments starting from the distal end of the tibial nerve and proceeding in the proximal direction until a reflex response is observed (reaction site). The distance between this site and the crush site is defined as ‘the regeneration distance’ (broken arrow). (B) Nerve pinch test after immediate GM6001 therapy in crushed sciatic nerve compared to vehicle, expressed as mean regeneration distance (mm) ± SD (n = 6–8/group, **, p < 0.01). (C) Schematic representation of the analyzed 3 mm crushed nerve segments (not to scale), immediately proximal (P), immediately distal (D) and 22 to 25 mm distal (D22) to the crush site. (D) Western blot for GAP-43 in the segments described in panel C. A representative of 4 blots is shown. The graph represents the mean of GAP-43 to β-actin ratios in D22 segment in n = 4/group ± SEM, *, p < 0.05. Sham-operated (Sh) nerves are used as controls. (E) GAP-43 immunofluorescence in longitudinal D22 segments after vehicle or MMPi therapy, representative micrograph of n = 3/group. Bar = 25 µm.

Western Blotting

Three-mm-long sciatic nerve segments (Fig. 1C) were collected in n = 4/group, snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Protein extraction was performed in lysis buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP 40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL aprotinin and leupeptin, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Equal amounts (30 µg) of protein, determined with BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), were separated by SDS-PAGE using Laemmli buffer system and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using an iBlot dry blotting system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 20 V for 7 minutes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), incubated with rabbit anti-GAP-43 or mouse anti-β-actin antibody (see below) in 5% bovine serum albumin overnight at 4°C, washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, 1: 5,000). The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Elite, Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Densitometry of mean GAP-43 to β-actin ratios was in each group (n = 4) using NIH Image J 1.38 software.

In Vivo BrdU Labeling and Detection

Endoneurial BrdU incorporation was studied as described (15, 29). Rats (n = 5/group) received i.p. BrdU (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, 100 mg/kg) or vehicle (1 mM Tris, 0.8% NaCl, 0.25 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) injection 2 and 4 days after sham or sciatic nerve crush surgery and MMPi or vehicle treatment. In a separate set of experiments, rats (n = 4/group) received intra-sciatic mitomycin, as described above, followed by nerve crush surgery and MMPi or vehicle. At 5 days after nerve crush, animals were anesthetized and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and killed, as described above. Sciatic nerves were isolated, post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, rinsed, cryoprotected in graded sucrose, embedded into OCT compound in liquid N2 and cut into 10-µm-thick longitudinal sections. The sections were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), hydrolyzed in 2N HCl in PBS for 30 minutes, digested with 0.01% Trypsin for 30 minutes at 37°C and washed with PBS. Non-specific binding was blocked with 10% normal goat serum, followed by mouse or rat anti-BrdU antibody (below) for 2 hours at 37°C, PBS rinse and goat anti-mouse Alexa 564 (red) antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at RT. Imaging was performed using a Leica DMR fluorescent microscope.

Antibodies

For immunofluorescence and Western blotting the following antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit anti-rat GAP-43 (Chemicon, 1:1,000), mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma, 1:10,000), polyclonal anti-S100 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, 1:400), polyclonal rabbit anti-CD68 (ED1 subclone, Abcam, Cambridge, MA; 1:100), polyclonal rabbit anti-von Willebrand factor (Abcam, 1:1000), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Dako, 1:500), rabbit anti-myelin protein zero (P0, Protein Tech Group, IL, 1:150), mouse anti-BrdU (Sigma, 1:1000) and rat anti-BrdU antibody (Abcam, 1:250). All primary antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin.

Immunofluorescence and Quantitative Morphometry

Cryoprotected and OCT-embedded sciatic nerve sections were rehydrated in graded ethanol and PBS. 5% sodium borohydride in 1% dibasic sodium phosphate buffer was applied for 5 minutes to block endogenous aldehyde groups. Antigen Retrieval Solution (Dako) was applied for 5 minutes at 95°C, then for 20 minutes at RT. Non-specific binding was blocked with 10% normal rabbit or goat serum followed by primary antibody (above) incubation overnight at 4°C. Following BrdU labeling, 10% rabbit or goat serum was re-applied, followed by the second primary antibody for 1 hour at RT, a TBS rinse containing 0.1% Tween 20 and second secondary antibody for 1 hour at RT or overnight at 4°C. For secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody conjugated to Alexa 564 (red) or Alexa 488 (green) were used from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, 1:200). TBS was used for all washes. Sections were mounted using Slowfade gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes). Signal specificity was controlled by omitting the primary antibody or replacing it with the appropriate normal IgG. Imaging was performed using a Leica DMR fluorescent microscope and Openlab 4.0 software (Improvision, Inc., Waltham, MA).

Immunoreactive cell profiles for BrdU (red), CD68+ macrophages (green) or for colocalization (yellow) of BrdU with CD68 or with S100 were quantified in 4 animals per group, 3 sections per animal, 4 randomly selected areas per section in 10-mm longitudinal distal and proximal sciatic nerve segments, using Openlab 4.0 software (Improvision). All quantifications were done at 40× objective magnification by an experimenter blinded to the experimental groups.

Real-time RT-qPCR

Taqman primers and probes for rat MBP (NM_017026.2), P0 (NM_017027.1) and GFAP (NM_017009.2) were obtained from Applied Biosystems Inc. (Foster City, CA). Distal and proximal to crush nerve segments were collected and stored in RNA-later (Ambion, Austin, TX) at −20°C. RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) and treated with RNAse-free DNAse (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The RNA purity was verified by OD260/280 absorption ratio of ~2.0. A SuperScript first-strand RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) was used to synthesize cDNA. Gene expression was measured by real-time qPCR (MX4000, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using 50 ng of cDNA and 2x Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with a one-step program (95°C for 10 minutes, 95°C for 30 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute for 50 cycles). Duplicate samples without cDNA (no-template control) showed no contaminating DNA. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a normalizer gene. Relative mRNA levels were quantified in 4 to 8 animals per group and calibrated to sham-operated nerves using the comparative Ct method (30). A fold change was determined by the MX4000 software as described (31).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using KaleidaGraph 4.03 or SPSS 16.0 software by unpaired Student t-test or one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Because spatiotemporal activity of various MMP family members spans from hours to days following sciatic nerve damage (11, 12, 14, 16, 17), the specific, broad-spectrum MMPi GM6001 treatment was administered immediately after sciatic nerve crush and daily thereafter for the duration of the study.

MMP Inhibition Enhances the Rate of Axonal Regeneration

Nerve pinch test determines the extent of axonal regrowth by measuring the distance between crush injury and the most distal point on the nerve that produces a reflex withdrawal response when pinched with forceps (7, 26, 27) (Fig. 1A). Based on the anticipated speed of sciatic regrowth, the test was performed between 3 and 7 days after nerve crush (7). Nerve pinch test demonstrated the significant increase in regeneration distance after MMPi treatment (23.6 ± 0.87 mm) compared to vehicle (18.6 ± 1.12 mm) at 5 days after crush (Fig. 1B).

GAP-43, an axonally transported phosphoprotein found on the inside membrane of regenerating axons (2), was quantified by Western blotting and immunofluorescence in the following 3-mm nerve segments: immediately proximal (P), immediately distal (D) and 22 to 25 mm distal (or D22) to the crush site (Fig. 1C). D22 was selected for MMPi- and vehicle-treated groups based on their anticipated difference in the content of regenerating fibers. No significant difference in GAP-43 levels was observed between the treatments in the segments immediately distal and proximal to crush injury (Fig. 1D), consistent with the conclusion that MMPi is not likely to affect the number of regenerative fibers or their collateral branches. A statistically significant increase in GAP-43 expression was seen in the D22 segment of MMPi-treated nerves compared to vehicle (Fig. 1D, E), corresponding to their accelerated rate of regeneration determined by pinch testing.

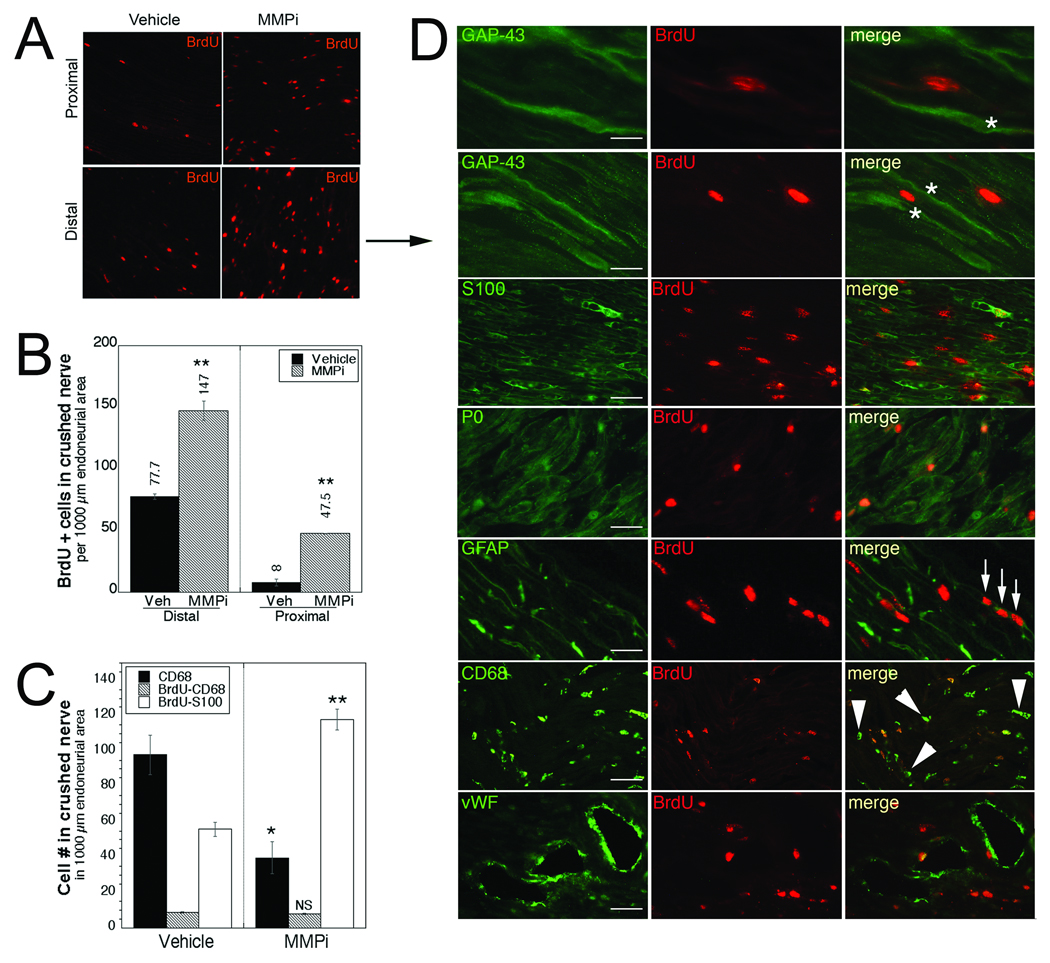

Increased Incidence of Mitotic SCs after MMP Inhibition

BrdU+ profiles were significantly greater after MMPi compared to vehicle treatment in both distal and proximal nerve segments (Fig. 2A, B). The dividing cells were identified by colocalization of BrdU with GAP-43 for regenerating axons (26), S100 protein for SCs of all phenotypes, GFAP for de-differentiating and nmSCs, P0 for mSCs (4) (both nmSCs and mSCs undergo mitosis after sciatic nerve injury [3, 32]), CD68 for macrophages and von Willebrand factor for endothelial cells that undergo mitosis during revascularization (33). Many BrdU+ mitotic cells in were associated with GAP-43+ regenerating axons (Fig. 2D). The dividing cells were identified as S100-, P0- and GFAP+ SCs. Occasional endothelial cells and macrophages colocalized with BrdU. As indicated by the arrowheads in Figure 2D, many CD68+ cells were not BrdU+. Quantification of BrdU+ SCs and macrophages indicated a substantial increase of dividing SCs but not macrophages in MMPi-treated compared to vehicle-treated nerves (Fig. 2C). It is important to note that total counts of CD68+ macrophages were reduced with MMPi treatment (Fig. 2C), consistent with earlier reports (14, 17, 34).

Figure 2.

Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (MMPi) GM6001 treatment promotes Schwann cell (SC) mitosis in regenerating nerves. (A) Bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (red) in distal and proximal crushed sciatic nerves after immediate GM6001 or vehicle (Veh) treatment. BrdU was administered at 2 and 4 days after crush. (B) Quantitative morphometry of the mean BrdU+ cells ± SEM. (C) Mean CD68+, CD68/BrdU+, or S100/BrdU+ profiles ± SEM in 1000 µm2 of endoneurial area. Panels B and C were based on n = 4/group, 2 sections/n, 3 randomly selected areas per section at 400× magnification. **, p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test). (D) Dual-immunofluorescence for BrdU (red) with phenotypic cell markers (green) in distal segments of MMPi-treated nerves. Dividing cells are identified in association with regenerating axons (GAP-43, asterisks); SCs (S100), myelinating SCs (mSCs) (P0) and de-differentiating/nmSCs (GFAP); macrophages (CD68) and endothelial cells (von Willebrand factor, vWF). Arrows indicate 3 mitotic cells in a row. Arrowheads point to macrophages/monocytes that have not taken up BrdU. Representative micrographs of n = 4/group. Scale bars: P0, CD68, vWF = 40 µm; GAP-43 (top micrograph), S100, GFAP = 25 µm; GAP-43 (second micrograph) = 10 µm.

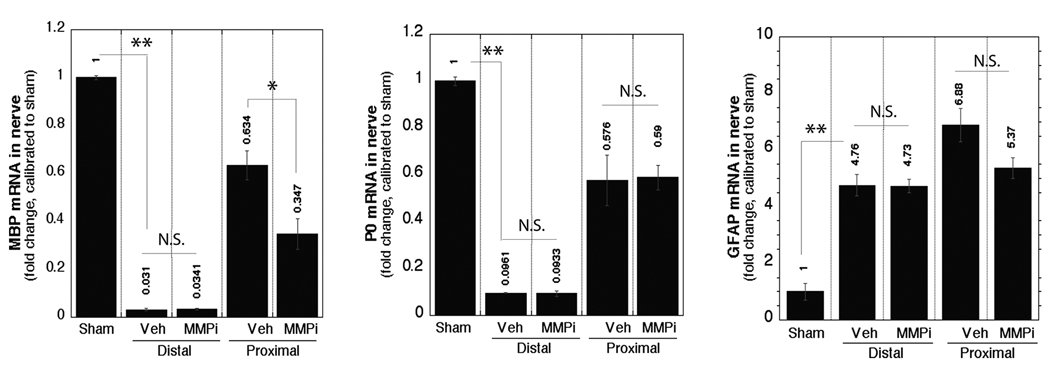

MMP Inhibition Promotes De-differentiation of Myelinating SCs

Sciatic nerve injury stimulates de-differentiation of mSCs prior to mitosis (3, 32). Since many P0-reactive mSCs were BrdU+ in MMPi-treated nerves, we analyzed the effect of MMPi therapy on their de-differentiation. After vehicle treatment, MBP and P0 mRNA levels sharply declined in distal and only slightly in proximal nerve segments, consistent with the reported observations at 5 days of sciatic nerve injury (35, 36) (Fig. 3). Increased GFAP mRNA was observed distal and proximal to injury, as anticipated from the earlier reports (3, 32). MMPi therapy further reduced MBP mRNA only in the proximal segment, producing no change in P0 or GFAP mRNA levels in either segment at the analyzed time-point. These data indicate that MMPs regulate MBP mRNA expression during peripheral nerve injury in vivo in addition to their control of MBP proteolysis (14, 37),

Figure 3.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) control myelin basic protein (MBP) mRNA expression in regenerating nerves. Real-time Taqman RT-qPCR for MBP, P0 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in crushed sciatic nerves after immediate MMP inhibitor (GM6001) or vehicle (Veh) treatment normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and calibrated to sham. The mean ± SEM of n = 4–6/group, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test). N.S. = not significant.

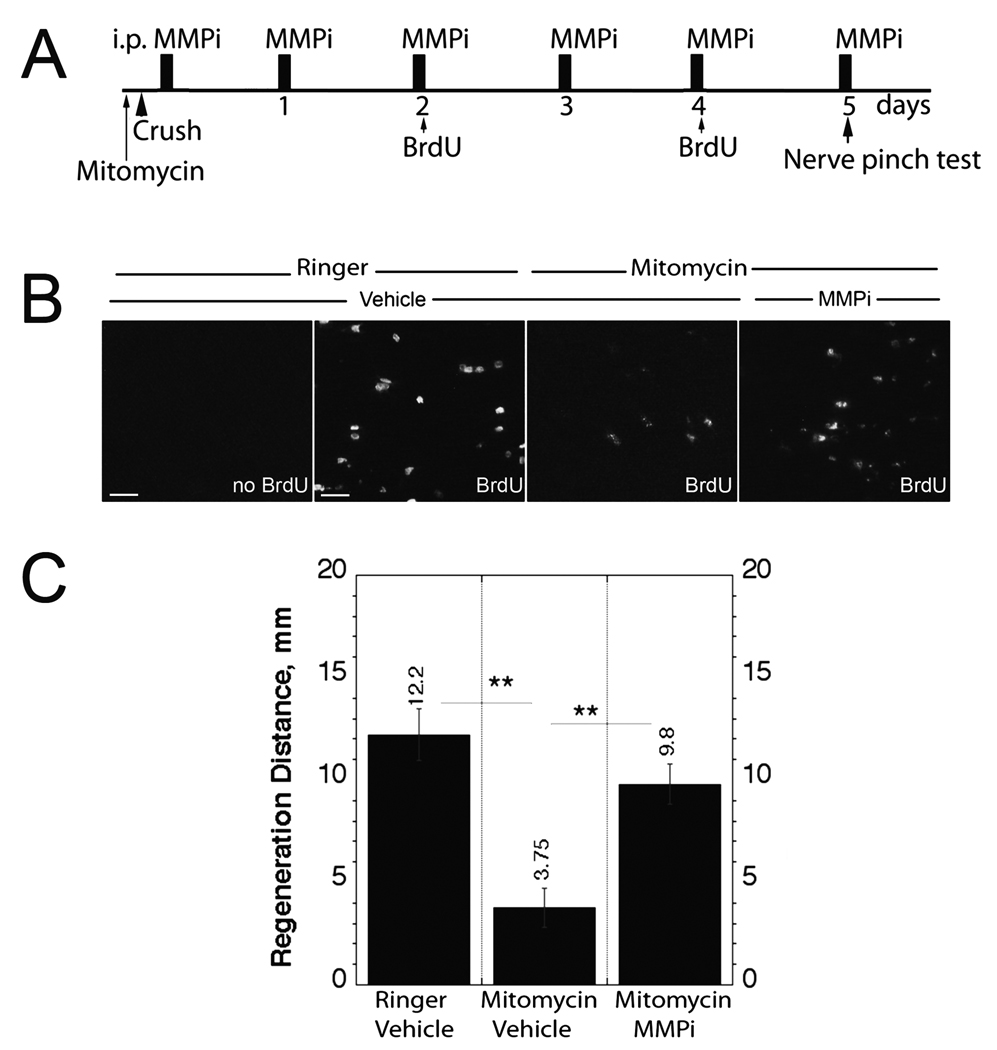

Reversal of the Effect of Anti-mitogenic Mitomycin in Inhibition of Nerve Regrowth

Intra-sciatic mitomycin treatment was used to inhibit endoneurial cell proliferation (23–25) (Fig. 4A). As anticipated, intra-sciatic mitomycin significantly reduced the numbers of BrdU+ cells in the distal segment of crushed nerve relative to Ringer’s solution control (Fig. 4B). Daily MMPi treatment reversed this action of mitomycin, indicating an increase in BrdU-reactive cells compared to mitomycin alone (Fig. 4B). Mitomycin drastically reduced the regeneration distance (3.75 mm ± 0.75) compared to the control (12.2 mm ± 0.75) and MMPi treatment administered immediately after injury reversed this mitomycin-induced suppression of nerve regrowth relative to vehicle (9.8 mm ± 1.0) (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition (MMPi) reverses anti-mitotic and growth inhibitory actions of mitomycin in vivo. (A) Experimental schedule for intra-sciatic mitomycin administration immediately prior to sciatic nerve crush surgery, followed by daily experimental GM6001therapy, bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) injection (at day 2 and day 4) and nerve pinch test at day 5 after crush injury. (B) BrdU incorporation in distal crushed nerve segments that received BrdU, mitomycin, MMPi or respective vehicle treatments. Representative micrographs of n = 4/group; bar = 25 µm. (C) Nerve pinch test after intra-sciatic mitomycin, immediate and daily MMPi or respective vehicle treatments. The mean regeneration distance (mm) ± SEM of n = 4/group, analyzed by one-way ANOVA (**, p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Peripheral nerve regeneration relies on SCs to undergo rapid proliferation between 2 and 4 days after injury and to produce a sufficient number of cells that can pair with and provide molecular guidance to growing axons. We assessed whether MMP inhibition, which promotes SC proliferation in vitro (15), contributes to peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. We show that systemic daily i.p. MMPi treatment for 5 days initiated immediately after rat sciatic nerve crush i) enhanced the rate of nerve fiber regrowth by promoting SC mitosis, ii) reversed the action of anti-mitogenic mitomycin to inhibit axonal regeneration, indicating that pro-mitotic MMPi action contributes to its growth-promoting ability, and iii) contributed to SC de-differentiation via selective inhibition of MBP mRNA expression in vivo. The latter finding adds to the established role of MMPs in myelin proteolysis (14, 37, 38) and regulation of ErbB and other trophic signaling pathways in SCs (15, 39).

Early Events of Peripheral Nerve Injury Under MMP Control

The enhanced sensory nerve fiber regrowth after GM6001 therapy established by nerve pinch test in vivo is consistent with its reported promotion of DRG neurite outgrowth in vitro (18). The effect of MMPi on regeneration of motor fibers that do not elicit a withdrawal reflex during nerve pinch test (26), however, remains to be determined. Since GM6001 therapy facilitates motor recovery after spinal cord injury (21), this is a likely action in injured peripheral nerve.

After spinal cord injury, immediate GM6001 treatment inhibits vascular permeability and neuroinflammation associated with early peak of MMP-9 whereas extended treatment was not effective due to MMP-2 action in wound healing (21, 40). Likewise, MMPs act differentially in peripheral nerve and distinct mechanisms of MMP induction may relate to their differential actions in nerve repair. For example, pre-degeneration of cultured sciatic nerve explants with MMP-2, but not MMP-9, is beneficial to growth of DRG neurons by degradation of inhibitory chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (41, 42). For example, MMP-9, but not MMP-2, is upregulated immediately after peripheral nerve injury (11, 14, 16, 17) and its expression in SCs is induced by proinflammatory (tumor necrosis factor [TNF], lipopolysaccharide) but not trophic (e.g. nerve growth factor, neuregulin-1 [NRG-1]) stimuli in vitro (15). Early inhibition of neuroimmune activity by anti-TNF therapy enhances the rate of sciatic nerve regeneration (28).

The promotion of axonal growth by MMPi may relate to protection from MMP-9-mediated neuroinflammation and macrophage infiltration (14, 17, 34). Indeed, macrophages can suppress dystrophic DRG neurite outgrowth by physical attack and retraction of axonal sprouts (43); inhibition of MMP-9, but not of MMP-2 results in resumption of neurite growth by reversing this macrophage action (44). After MMPi treatment, reduced numbers of macrophages, (even in the absence of its effect on CD68+ cell mitoses), is thought to be due to the ability of MMPi to prevent breakdown of the blood-nerve barrier (11, 17, 34). Monocyclic, an emerging neuroprotective tetracycline (45) and non-specific MMPi (46), reduces MMP-9 expression in injured nerves and improves nerve regeneration by its anti-ischemic effect on SCs despite impaired revascularization (33). Mitoses of endothelial cells indicate ongoing revascularization in MMPi-inhibited nerves, so the potentially negative effects of GM6001 on angiogenesis (47) during nerve repair deserve future consideration. Overall, establishing the spatiotemporal activities and specific roles of MMP family members is essential for the development of successful selective MMPi therapies to stimulate nerve repair.

MMPs and Regulation of SC Signaling and Function

MMPi-mediated increases in SC mitosis in vivo are consistent with earlier findings in cultured SCs (15, 48). We found that the numbers of BrdU+ cells were substantially higher in the distal nerve stump where SC proliferation occurs and spread only a few millimeters proximal to a lesion (49). Nevertheless, MMPi was relatively more effective in promoting cell mitoses in proximal (5-fold) compared to distal (2-fold) stumps. MMPs control proteolysis of myelin proteins (18, 37), and the lesser numbers of mitotic cells in the distal stumps of MMPi-treated nerves might be due to their reduced content of pro-mitogenic myelin degradation products and macrophages (14). An increased number of SCs in the proximal stump may suggest that more collateral branching exists after MMPi treatment. Inasmuch as the nerve pinch test measures the regeneration distance after injury, we conclude that MMPi promotes the rate of axonal regrowth rather than the intensity of axonal branching. This conclusion is supported by the finding that GAP-43 expression was elevated only in the distal D22 segment of the MMPi-treated nerves, corresponding to their enhanced regeneration distance.

MMPs may stimulate SC migration during myelin formation of DRG neurons (50). Because during nerve regeneration SCs typically migrate from the injury site in the retrograde direction towards the proximal stump (49), the proximal accumulation of mitotic SCs in MMPi-treated and MMP-9-null nerves (15) may represent a compensatory response to the reduced SC migration. Migrating SCs guide axons by deposition of growth-promoting laminin (8), which suggests that MMPi may continue to support neurite outgrowth by protecting laminin from degradation (51), despite its potentially negative regulation of SC migration (52). MMPi can also stimulate growth of DRG neurons by preventing the formation of growth-inhibitory fragments of myelin-associated glycoprotein (18).

MMPs control a plethora of signal transduction pathways through proteolytic cell surface and extracellular ligand or receptor processing (51, 53), but understanding of their mechanisms of action in SCs is only starting to emerge. MMP-3 suppresses SC mitoses through the formation of anti-mitogenic fibronectin fragments (48); MMP-9 and MMP-28 can stimulate ERK MAPK signaling in SCs by activation of the NRG-1/ErbB ligand receptor system (15, 39), and ErbB inhibitor pre-treatment reverses MMP-9-mediated suppression of SC mitosis (15). In the CNS, MMP-12 and MMP-9 regulate myelination through release of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) from IGFBP6 binding protein (54), and MMP-9 can utilize the IGF-1 receptor to activate SC ERK signaling (15). Both catalytically active MMP-9 and its catalytically inept, substrate-binding hemopexin domain (MMP-9-PEX) activate ERK in SCs by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 receptor agonist action (52). Because MMP-9-PEX also acts as an antagonist to endogenous MMP-9 (55), cautious interpretation of the action of MMP-9-PEX in MMP-9-rich environments of injured nerve and denervated SCs is warranted. MMP-9 induces 2 distinct phases of ERK activation in both differentiated and undifferentiated SCs (15). Thus, the functional outcome of MMP-mediated ERK activation may depend on SC phenotype or microenvironment. For example, MMP-28 is thought to utilize NRG-1/ErbB-ERK signaling for myelination of DRG neurons (39).

Multifactorial Regulation of Myelination and Neuron Survival

De-differentiation of mSCs is a pre-requisite for their division (4), as indicated by a characteristically sharp decline in MBP and P0 mRNA in distal nerve with only a slight reduction in the proximal segments (Fig. 3) (35, 36). MMPi reduced MBP mRNA only in the proximal stump, where its levels remained high or possibly specifically in association with regenerating nerve. Both MBP and P0 are late components of myelination (4), but MMPi influenced the expression of MBP but not of P0. Similarly, MMPi protects MBP but not P0 from proteolysis (14). Thus, it is possible that an MMPi-mediated decline in MBP mRNA is the result of accumulated levels of its protein; it may also reflect selective roles of MMPs in regulation of NRG-1/ErbB and other pathways (15) of SC-driven myelination (56).

The increase in GFAP in both distal and proximal stumps of injured nerve (Fig. 3) also indicates de-differentiation of both mSCs and nmSCs (3, 32). MMPi had no effect on GFAP mRNA expression at 5 days after crush. The present study focused on the early events of nerve repair, but since MMPs contribute to the formation of CNS myelin (54), MMPi effects on re-differentiation of post-mitotic SCs and axonal remyelination at later time points should be determined in the future. The increased numbers of mitotic SCs along regenerating fibers we observed may explain the formation of shorter myelin internodes of myelinating DRG neurons after MMPi treatment in vitro (50).

MMPs promote neuronal apoptosis (19, 57, 58), including that of DRG neurons (14, 59). Thus, the effect of MMPi on neuronal survival or other effects of MMPs on neuronal soma during nerve repair also remain to be investigated in the future.

Overall, the present study provides the first evidence that immediate MMPi therapy supports axonal regeneration in vivo and that it acts by stimulation of SC division. Whether or not MMP-mediated suppression of SC mitosis and de-differentiation at the early stages of nerve damage leads to reduced survival of SCs, it does contribute to phenotypic remodeling of SCs, myelin protein expression and proteolysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Amber Millen for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work is supported by NIH/NINDS R21 NS060307-01 and the Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award to V.I.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stoll G, Jander S, Myers RR. Degeneration and regeneration of the peripheral nervous system: From Augustus Waller's observations to neuroinflammation. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2002;7:13–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2002.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fawcett JW, Keynes RJ. Peripheral nerve regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemence A, Mirsky R, Jessen KR. Non-myelin-forming Schwann cells proliferate rapidly during Wallerian degeneration in the rat sciatic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1989;18:185–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01206661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jessen KR, Mirsky R. The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrn1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baichwal RR, Bigbee JW, DeVries GH. Macrophage-mediated myelin-related mitogenic factor for cultured Schwann cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:1701–1705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murinson BB, Archer DR, Li Y, Griffin JW. Degeneration of myelinated efferent fibers prompts mitosis in Remak Schwann cells of uninjured C-fiber afferents. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1179–1187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1372-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McQuarrie IG, Grafstein B, Gershon MD. Axonal regeneration in the rat sciatic nerve: Effect of a conditioning lesion and of dbcAMP. Brain Res. 1977;132:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald D, Cheng C, Chen Y, Zochodne D. Early events of peripheral nerve regeneration. Neuron Glia Biol. 2006;2:139–147. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X05000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholz J, Woolf CJ. The neuropathic pain triad: Neurons, immune cells and glia. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1361–1368. doi: 10.1038/nn1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes PM, Wells GM, Perry VH, Brown MC, Miller KM. Comparison of matrix metalloproteinase expression during Wallerian degeneration in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Neuroscience. 2002;113:273–287. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shubayev VI, Myers RR. Endoneurial remodeling by TNFalpha- and TNFalpha-releasing proteases. A spatial and temporal co-localization study in painful neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2002;7:28–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8027.2002.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Fleur M, Underwood JL, Rappolee DA, Werb Z. Basement membrane and repair of injury to peripheral nerve: Defining a potential role for macrophages, matrix metalloproteinases, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2311–2326. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Platt CI, Krekoski CA, Ward RV, Edwards DR, Gavrilovic J. Extracellular matrix and matrix metalloproteinases in sciatic nerve. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:417–429. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi H, Chattopadhyay S, Kato K, et al. MMPs initiate Schwann cell-mediated MBP degradation and mechanical nociception after nerve damage. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;39:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chattopadhyay S, Shubayev VI. MMP-9 controls Schwann cell proliferation and phenotypic remodeling via IGF-1 and ErbB receptor-mediated activation of MEK/ERK pathway. Glia. 2009;57:1316–1325. doi: 10.1002/glia.20851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chattopadhyay S, Myers RR, Janes J, Shubayev V. Cytokine regulation of MMP-9 in peripheral glia: Implications for pathological processes and pain in injured nerve. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shubayev VI, Angert M, Dolkas J, Campana WM, Palenscar K, Myers RR. TNFalpha-induced MMP-9 promotes macrophage recruitment into injured peripheral nerve. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milward E, Kim KJ, Szklarczyk A, et al. Cleavage of myelin associated glycoprotein by matrix metalloproteinases. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;193:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manabe S, Gu Z, Lipton SA. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 via neuronal nitric oxide synthase contributes to NMDA-induced retinal ganglion cell death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4747–4753. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sifringer M, Stefovska V, Zentner I, et al. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in infant traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25:526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noble LJ, Donovan F, Igarashi T, Goussev S, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases limit functional recovery after spinal cord injury by modulation of early vascular events. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7526–7535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gijbels K, Galardy RE, Steinman L. Reversal of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with a hydroxamate inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2177–2182. doi: 10.1172/JCI117578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YY, McDonald D, Cheng C, Magnowski B, Durand J, Zochodne DW. Axon and Schwann cell partnership during nerve regrowth. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:613–622. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171650.94341.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall SM, Gregson NA. The effects of mitomycin C on remyelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature. 1974;252:303–305. doi: 10.1038/252303a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellegrino RG, Spencer PS. Schwann cell mitosis in response to regenerating peripheral axons in vivo. Brain Res. 1985;341:16–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seijffers R, Mills CD, Woolf CJ. ATF3 increases the intrinsic growth state of DRG neurons to enhance peripheral nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7911–7920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5313-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gutmann E, Sanders FK. Recovery of fibre numbers and diameters in the regeneration of peripheral nerves. J Physiol. 1943;101:489–518. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1943.sp004002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato K, Liu H, Kikuchi S, Myers RR, Shubayev VI. Immediate anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (etanercept) therapy enhances axonal regeneration after sciatic nerve crush. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:360–368. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng C, Zochodne DW. In vivo proliferation, migration and phenotypic changes of Schwann cells in the presence of myelinated fibers. Neuroscience. 2002;115:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu QG, Midha R, Martinez JA, Guo GF, Zochodne DW. Facilitated sprouting in a peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2008;152:877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keilhoff G, Schild L, Fansa H. Minocycline protects Schwann cells from ischemia-like injury and promotes axonal outgrowth in bioartificial nerve grafts lacking Wallerian degeneration. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siebert H, Dippel N, Mader M, Weber F, Bruck W. Matrix metalloproteinase expression and inhibition after sciatic nerve axotomy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:85–93. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeBlanc AC, Poduslo JF. Axonal modulation of myelin gene expression in the peripheral nerve. J Neurosci Res. 1990;26:317–326. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta SK, Poduslo JF, Mezei C. Temporal changes in PO and MBP gene expression after crush-injury of the adult peripheral nerve. Brain Res. 1988;464:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gijbels K, Proost P, Masure S, Carton H, Billiau A, Opdenakker G. Gelatinase B is present in the cerebrospinal fluid during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and cleaves myelin basic protein. J Neurosci Res. 1993;36:432–440. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490360409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandler S, Coates R, Gearing A, Lury J, Wells G, Bone E. Matrix metalloproteinases degrade myelin basic protein. Neurosci Lett. 1995;201:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner SR, Dotzlaf JE, Smith RC. MMP-28 as a regulator of myelination. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu JY, McKeon R, Goussev S, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 facilitates wound healing events that promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9841–9850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1993-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krekoski CA, Neubauer D, Graham JB, Muir D. Metalloproteinase-dependent predegeneration in vitro enhances axonal regeneration within acellular peripheral nerve grafts. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10408–10415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10408.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuo J, Ferguson TA, Hernandez YJ, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Muir D. Neuronal matrix metalloproteinase-2 degrades and inactivates a neurite-inhibiting chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5203–5211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05203.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horn KP, Busch SA, Hawthorne AL, van Rooijen N, Silver J. Another barrier to regeneration in the CNS: Activated macrophages induce extensive retraction of dystrophic axons through direct physical interactions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9330–9341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busch SA, Horn KP, Silver DJ, Silver J. Overcoming macrophage-mediated axonal dieback following CNS injury. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9967–9976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1151-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zemke D, Majid A. The potential of minocycline for neuroprotection in human neurologic disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:293–298. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000150867.98887.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paemen L, Martens E, Norga K, et al. The gelatinase inhibitory activity of tetracyclines and chemically modified tetracycline analogues as measured by a novel microtiter assay for inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moses MA. The regulation of neovascularization of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Stem Cells. 1997;15:180–189. doi: 10.1002/stem.150180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muir D, Manthorpe M. Stromelysin generates a fibronectin fragment that inhibits Schwann cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:177–185. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oderfold-Nowak B, Niemierko S. Synthesis of nucleic acids in the Schwann cells as the early cellular response to nerve injury. J Neurochem. 1969;16:235–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1969.tb05941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehmann HC, Kohne A, Bernal F, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 is involved in myelination of dorsal root ganglia neurons. Glia. 2009;57:479–489. doi: 10.1002/glia.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mantuano E, Inoue G, Li X, et al. The hemopexin domain of matrix metalloproteinase-9 activates cell signaling and promotes migration of schwann cells by binding to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11571–11582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3053-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanderson MP, Dempsey PJ, Dunbar AJ. Control of ErbB signaling through metalloprotease mediated ectodomain shedding of EGF-like factors. Growth Factors. 2006;24:121–136. doi: 10.1080/08977190600634373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Larsen PH, DaSilva AG, Conant K, Yong VW. Myelin formation during development of the CNS is delayed in matrix metalloproteinase-9 and -12 null mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2207–2214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1880-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roeb E, Schleinkofer K, Kernebeck T, et al. The matrix metalloproteinase 9 (mmp-9) hemopexin domain is a novel gelatin binding domain and acts as an antagonist. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50326–50332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lemke G. Neuregulin-1 and myelination. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:pe11. doi: 10.1126/stke.3252006pe11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim YS, Kim SS, Cho JJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-3: A novel signaling proteinase from apoptotic neuronal cells that activates microglia. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3701–3711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4346-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauppinen TM, Swanson RA. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 promotes microglial activation, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated neuron death. J Immunol. 2005;174:2288–2296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen HX, O'Barr TJ, Anderson AJ. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes promote neurotoxicity through release of matrix metalloproteinases, reactive oxygen species, and TNF-alpha. J Neurochem. 2007;102:900–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]