Abstract

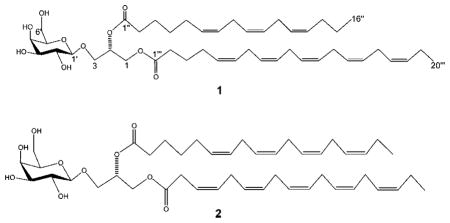

Two monogalactosyl diacylglycerols, 1 and 2, were isolated from the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, using the patented ApopScreen cell-based screen for apoptosis-inducing, potential anticancer compounds. The molecular structures of the galactolipids were determined using a combination of NMR, mass spectrometry, and chemical degradation. The bioactivities were confirmed using a specific apoptosis induction assay based on genetically engineered mammalian cell lines with differential, defined capacities for apoptosis. The galactolipids induce apoptosis in micromolar concentrations. This is the first report of apoptosis induction by galactolipids.

The oceans are the largest ecosystem of Earth and hold great, unexplored potential for drug discovery. One of the most important photosynthetic eukaryotes in marine ecosystems are the diatoms,1 single-celled algae surrounded by a silica-derived wall. There are estimated to be ~106 species of diatoms,2,3 which makes them ~4-fold more diverse than angiosperms. These organisms rose to ecological prominence over the past 40 million years, and in part, their success has been attributed not only to efficient resource acquisition strategies but also to allelochemical production that may favor their selection over competitors. Hence, we examined whether this group of organisms produces novel compounds capable of inducing apoptosis.

The screening of organic extracts from marine algae and cyanobacteria for mechanism-based anticancer agents has become increasingly efficient and has led to the discovery of new chemo-types showing antiproliferative properties.4,5 Cytotoxic chemo-therapeutics currently in use for the treatment of cancer rely on the ability to selectively target proliferating cells, which are enriched in tumors. Tumor cells progressively evolve genetic mutations that enable not only cell proliferation but also resistance to apoptosis, a cell suicide pathway that is the cellular response to oncogene activation or irreparable cellular damage.6–9 Effective cancer therapeutic strategies often rely on preferential and efficient induction of apoptosis in tumor cells. Progressive exposure to such molecules commonly leads to selection of resistant cells that are therapeutically associated with both tumor progression and resistance to chemotherapy.6–9 While many conventional cytotoxic chemotherapeutics trigger apoptosis indirectly by inflicting cellular damage, recent efforts have been directed to developing agents that specifically target or activate a caspase cascade that leads to apoptosis.10

In our ongoing effort to discover and develop new marine natural product biomedicinals, we have screened extracts from several marine organisms and have found that those isolated from a cultured marine diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, possessed an ability to specifically induce apoptosis in immortal mammalian epithelial cells. Subsequently, extracts were subjected to ApopScreen bioas-say-guided purification, which resulted in the isolation of two monogalactosyl diacylglycerols (1 and 2), which we demonstrate are capable of inducing apoptosis in the same cell lines. To our knowledge, this is the first report of apoptosis induction by galactolipids.

Results and Discussion

The marine diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, was cultured in a F/2 medium at 18 °C under constant light (100 μmol m−2 s−1). Forty grams wet weight of the organism was extracted in methanol. One part of the methanol-soluble extract was dissolved in DMSO and was tested for apoptosis induction as assessed by the ApopScreen protocol.11,12 This cell-based assay is specific for the isolation and identification of apoptosis-inducing compounds. Two genetically matched immortal mouse epithelial cell lines are used: wild-type W2 with apoptosis function intact, and D3 with apoptosis function disabled through specific genetic deletion of both bax and bak (D3) (United States patent #US 6,890,716). D3 cells are completely and irreversibly defective for apoptosis, and yet all apoptosis regulatory mechanisms upstream of Bax and Bak (Bcl-2, Bim, etc.) remain intact.13 Importantly, the vast majority of human cancers with defects in apoptosis have the pathway disabled upstream of Bax and Bak. Thus, screening to identify compounds that have the capacity to kill W2 but not D3 cells should identify those that possess proapoptotic, and potentially anticancer, activity. Moreover, materials that indiscriminately kill both apoptosis-competent W2 and apoptosis-defective D3 cells can be used to eliminate those compounds that are nonspecifically toxic.11

The extract that induced apoptosis was subsequently purified by analytical RPHPLC. Using this strategy, two pure compounds with proapoptotic activity were isolated. Chemical structures of these two compounds (1 and 2) were ascertained by standard spectroscopic techniques, as described below.

The molecular formula of 1 was established as C45H70O10 on the basis of HR MALDI-TOFMS [m/z 793.4883 (M + Na)+ (calcd for C45H70O10Na, 793.4867)]. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1 indicated clearly the presence of a sugar and long-chain unsaturated fatty acid ester moieties, suggesting a glycoglycerolipid. Analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 1, together with 1H–1H COSY, multiplicity-edited HSQC, and HMBC experiments, led to the assignments of all the 1H and 13C NMR signals for the sugar and glycerol moieties, as shown in Table 1. One group of signals at δC 104.5, 71.6, 73.7, 69.5, 74.8, and 62.4 and δH 4.27 [(d, J = 6.8 Hz), H-1′], 3.63 [(dd, J = 6.8 Hz, 9.7 Hz), H-2′], 3.54 [(dd, J = 2.1 Hz, 9.7 Hz), H-3′], and 3.99 [(dd, J = 1.5 Hz, 2.1 Hz, H-4′] suggested a terminal β-D-galactopyranose unit. Moreover, the other group of signals at δC 63.1 70.4 and 68.4 and δH 4.22 [(dd, J = 6.8 Hz, 12.0 Hz), H-1a], 4.40 [(dd, J = 2.0 Hz, 12.0 Hz), H-1b], 5.28 [(m), H-2], 3.72 [(dd, J = 6.0 Hz, 11.0 Hz), H-3a], and 3.89 [(dd, J = 6.0 Hz, 11.0 Hz), H-3b] revealed a glycerol moiety. In the HMBC experiment, the anomeric proton H-1′ of the β-D-galactopyranosyl was correlated with the carbon C-3 of the glycerol moiety, and the protons H-1a,b and H-2 of the glycerol were correlated to the carbonyls C-1‴ (δC 173.3) and C-1″ (δC 173.5) of the fatty acid side chains, respectively.

Table 1.

NMR Spectroscopic Data of Compound 1 (300 MHz, CDCl3)

| position | δC | δH | HMBCa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-a | 1-b | 63.1 | CH2 | 4.22, dd (6.8,12.0) 4.40, dd (2.0,12.0) | 1″, 2 | ||||

| 2 | 70.4 | CH | 5.28, m | 1″ | |||||

| 3-a | 3-b | 68.4 | CH2 | 3.72, dd (6.0,11.0) 3.89, dd (6.0,11.0) | 1′, 1, 2 | ||||

| 1′ | 104.5 | CH | 4.27, d (6.8) | 3, 5′ | |||||

| 2′ | 71.6 | CH | 3.63, dd (6.8, 9.7) | 1′, 3′ | |||||

| 3′ | 73.7 | CH | 3.54, dd (2.1, 9.7) | 2′, 4′ | |||||

| 4′ | 69.5 | CH | 3.99, dd (1.5, 2.1) | 3′, 5′ | |||||

| 5′ | 74.8 | CH | 3.58, m | 6′, 4′ | |||||

| 6′-a | 6′-b | 62.4 | CH2 | 3.86, dd (7.0,12.0) 3.96, dd (5.0,12.0) | 5′ | ||||

| 1″ | 1‴ | 173.5 | qC | 173.3 | qC | ||||

| 2″ | 2‴ | 34.1 | CH2 | 33.5 | CH2 | 2.32, t (7.3) | 2.31, t (7.32) | 1″, 2″ | 1‴,2‴ |

| 3″ | 3‴ | 25.1 | CH2 | 25.1 | CH2 | 1.68, m | 1.72, m | 1″, 5″ | 1‴, 5‴ |

| 4″ | 4‴ | 29.7 | CH2 | 27.5 | CH2 | 1.33, m | 2.08, m | 6″ | 3‴, 5‴ |

| 5″ | 5‴ | 27.5 | CH2 | 130.4 | CH | 2.08, m | 5.36, m | 4″, 6″ | 7‴ |

| 6″ | 6‴ | 129.5 | CH | 129.0 | CH | 5.36, m | 5.36,m | 5″, 8″ | 7‴, 8‴ |

| 7″ | 7‴ | 127.81 | CH | 26.5 | CH2 | 5.36,m | 2.81, m | 8″,9″ | 6‴, 8‴ |

| 8″ | 8‴ | 26.5 | CH2 | 128.82 | CH | 2.81,m | 5.36, m | 7″,9″ | 7‴,9‴ |

| 9″ | 9‴ | 127.89 | CH | 128.34 | CH | 5.36, m | 5.36, m | 8″,10″ | 8‴,10‴ |

| 10″ | 10‴ | 128.10 | CH | 26.5 | CH2 | 5.36, m | 2.81, m | 9″,11″ | 9‴,11‴ |

| 11″ | 11‴ | 26.5 | CH2 | 128.63 | CH | 2.81, m | 5.36, m | 10″,12″ | 10‴,12‴ |

| 12″ | 12‴ | 128.05 | CH | 128.25 | CH | 5.36, m | 5.36, m | 11″,13″ | 11‴, 13‴ |

| 13″ | 13‴ | 128.39 | CH | 26.5 | CH2 | 5.36, m | 2.81, m | 12″,14″ | 12‴,14‴ |

| 14″ | 14‴ | 29.5 | CH2 | 128.51 | CH | 2.08, m | 5.36, m | 13″,15″,16″ | 13‴,15‴ |

| 15″ | 15‴ | 23.0 | CH2 | 128.19 | CH | 1.40, m | 5.36,m | 14″,16″ | 14‴,16‴ |

| 16″ | 16‴ | 13.8 | CH3 | 26.5 | CH2 | 0.91, t | (6.8) 2.81, m | 14″,15″ | 15‴,17‴ |

| 17‴ | 127.04 | CH | 5.36, m | 16‴,18‴ | |||||

| 18‴ | 132.09 CH | 5.36, m | 17‴, 19‴ | ||||||

| 19‴ | 20.0 | CH2 | 2.08,m | 18‴,20‴ | |||||

| 20‴ | 14.2 | CH3 | 0.97, t (7.2) | 18‴,19‴ | |||||

HMBC correlations, optimized for 8 Hz, are from proton(s) stated to the indicated carbon.

According to its molecular formula, the two acyl moieties of 1 must represent a total of 36 carbon atoms. 13C NMR indicated a total of 16 olefinic carbons (δC 127.04, 127.81, 127.89, 128.05, 128.10, 128.19, 128.25, 128.34, 128.39, 128.51, 128.63, 128.82, 129.0, 129.5, 130.24, 132.09) corresponding to eight double bonds. In addition, the strong signal at δC 26.5, δH 2.81 observed in the multiplicity-edited HSQC indicates the existence of several bis-allylic methylene carbons. Since bis-allylic carbon signals of Z-and E-isomers are observed at δC ca. 27 and ca. 32, respectively,14,15 the 26.5 ppm shift suggests that all double bonds have a cis-geometry (Z).

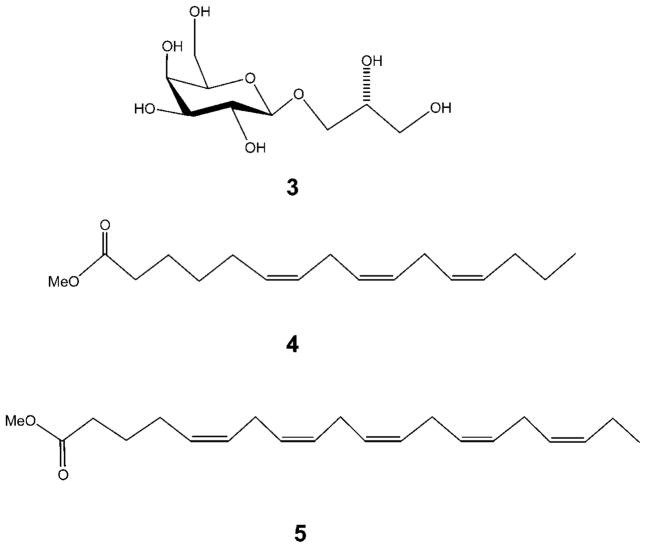

To deduce the exact nature of the polyunsaturated fatty acids, 1 was hydrolyzed in methanol/NaOMe (2 h). After routine workup of the reaction, the nonpolar organic extract was analyzed by GC-MS and ESIMS, and two ion peaks [M + H]+ at m/z 265.2166 and 317.2480 were observed, corresponding to hexadecatrienoic acid methyl ester (4) and eicosapentaenoic acid methyl ester (5), respectively. Upon regioselective enzymic hydrolysis of 1 with lipase enzyme type III in dioxane/H2O (1:1) at 37 °C for 4 h,16 only eicosapentaenoic acid was obtained, as analyzed by ESIMS and compared with an authentic sample. Thus, we concluded that an eicosapentaenoyl residue was attached to the C-1 position of the glycerol moiety in 1. The aqueous phase yielded a monogalactosyl glycerol (3), which was identical in all respects with (2R)-3-O-[β-D-galactopyranosyl]glycerol,17,18 confirming the stereochemistry of both the sugar and glycerol part in 1. Moreover, 3 was subjected to acid hydrolysis (2 N HCl, 30 min), and after workup and purification, β-D-galactose was obtained. The D-configuration of this sugar was confirmed by comparing its optical rotation with that reported in the literature for an authentic sample.19–21 The configuration at C-2 in the glycerol moiety of 1 is presumed to be S on the basis of a comparison of specific rotation with literature values.19 Consequently, the structure of 1 was characterized as (2S)-1-O-5,8,11,14,17-eicosapentaenoyl-2-O-6,9,12-hexadecatrienoyl-3-O-[β-D-galactopyranosyl]glycerol, a new compound that induces apoptosis in mammalian cell lines. Compound 1 is closely related to previously reported glycerolipids from marine diatoms Chaetoceros,22 Thalassiosira rotula,23 and Skeletonema costatum.24

The molecular formula of 2 was established as C45H68O10 on the basis of HR MALDI-TOFMS. The strong similarity of its NMR data to that of (2S)-1-O-3,6,9,12,15-octadecapentaenoyl-2-O-6,9,12,15-octadecatetraenoyl-3-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl-sn-glycerol revealed that 2 was a known compound that was previously isolated from the marine dinoflagellate Heterosigma akashiwo.25 The nature of the polyunsaturated fatty acid side chains of 2 was ascertained by the same methods described above.

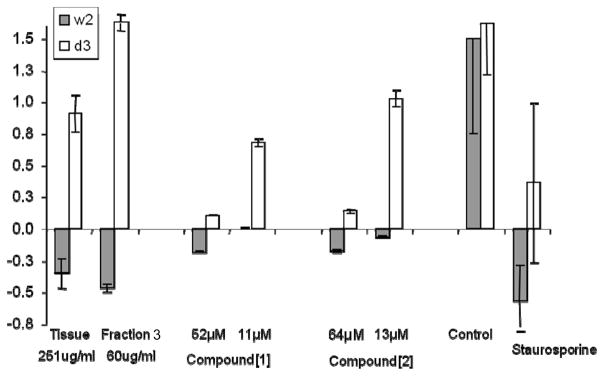

To assess the proapoptotic activities of these compounds as a marker for their potential anticancer efficacy, methanol-soluble fractions of P. tricornutum extracts were tested for apoptosis induction using the ApopScreen protocol as described above. To quantify apoptosis induction, viability was determined using an MTT assay.26 Growth was calculated as the difference between time 0 (addition of compound) and after 48 h exposure. Apoptosis induction was defined as at least 20% death of W2 cells and a 10% or higher growth of D3 cells.12 The optimal concentration of the compounds for apoptosis induction was determined on the basis of the dose response of the two cell lines by MTT assay. The results (Figure 3) reveal a significant induction of apoptosis by the whole extract (death of W2 35 ± 12%, growth of D3 of 91 ± 15%) and fraction 3 (death of W2 50 ± 3%, growth of D3 of 160 ± 7%), but only moderate induction by the isolated compounds. Death of W2 with compound 1 (52 μM) was 18% ± 1%, with growth of D3 at 10% ± 1%, and 18% ± 1% death and 14% ± 1% growth with compound 2 (64 μM), respectively. At a fifth of these concentrations, both compounds inhibited the growth of W2, but not D3. Thus, the monogalactosyl diacylglycerols we have isolated effectively and specifically activate apoptosis in immortalized mammalian epithelial cells. The increased activity of the crude materials could be due to a synergistic effect between the two isolated compounds 1 and 2 or with other compounds from the same fractions. This activity is, however, less significant compared to the apoptosis induction of diterpenes previously isolated from Xenia elongata using the same protocol.11

Figure 3.

Change in relative W2 and D3 cell viability by MTT assay 48 h after addition of whole cell tissue extract, fraction 3, 1, and 2 (1, 52 μM; 2, 64 μM). Staurosporine (0.1 μM), a known apoptosis inducer, and untreated cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Values are an average of five wells.

Monogalactosyldiacylglycerols are chloroplast membrane lipids in higher plants and algae. The increased attention to this class of natural products derives from the specific roles played by these compounds in the light-initiated reactions of photosynthesis and the considerable interest in their bioactivities, which include antiviral properties27 and antimitotic,28 tumor suppressor,29 antistress,30 and anti-inflammatory activity.19 This is the first report that monogalactosyldiacylglycerols induce apoptosis at micromolar concentration. The mechanism of action of these compounds has yet to be elucidated. Chloroplast-derived glycolipids and membrane-bound phospholipids have been shown to be the main substrates for the biosynthetic pathway that produces antiproliferative polyunsaturated aldehydes23,31 in wounded and nutrient-starved cells of marine diatoms.32–34 It is also known that fatty acid hydroperoxides display teratogenic and proapoptotic properties.35 It is conceivable that an enzymatic reaction (lipoxygenase/O2) of the two side chains of compound 1 would produce hydroperoxide-containing fatty acids, which, in turn, by enzymatic breakdown (lyase) would produce polyunsaturated aldehydes (decatrienal and octadienal).36,37 The whole part of the molecule may also play an important role in the structure and activity relationship. This was previously found in glycoglycerolipid analogues, which have gained importance in cancer chemoprevention due to their promising inhibitory effect on tumor growth. The fatty acyl chain length,38 its position, and the nature of the sugar moiety influence the activity.39 Galacto-sylglycerols are reported to be more potent than the corresponding glucosylglycerols with the same structural features. However, the anomeric configuration does not seem to affect the activity.40

The compounds described herein represent a potential platform for the development of new drugs with specific proapoptotic activity, and therefore, potential anticancer utility. This work describes the bioactivity of metabolites from the marine diatom P. tricornutum using a cell-based screen that we developed to identify potential proapoptotic compounds. P. tricornutum was used as a model organism because of the advanced knowledge in genetic and genomic resources of this organism, which provide a useful tool for future identification of biosynthetic key pathways for secondary metabolism.41,42 The vast majority of human solid tumors are of epithelial origin, and defects in apoptosis, mostly upstream of Bax and Bak, play important roles in both tumor suppression and mediation of chemotherapeutic responses. Consequently, efforts are increasingly focused on developing drugs that can reactivate the apoptotic pathway. The compounds identified here induce apoptosis upstream of Bax and Bak and may have a potential for use as anticancer agents that exploit the apoptosis pathway in tumor cells.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on a JASCO P 1010 polarimeter. UV and FT-IR spectra were obtained employing Hewlett-Packard 8452A and Nicolet 510 instruments, respectively. All NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance DRX300 spectrometer except for the 1H NMR of compound 3, which was recorded on a Varian-500 instrument (500 MHz). Spectra were referenced to residual solvent signals with resonances at δH/C 7.26/77.1 (CDCl3). GC/MS data were acquired on a Hewlett-Packard 5890 series II chromatograph with a Hewlett-Packard 5971 series mass selective detector. MALDI-TOF data were recorded on an Applied Biosystems 4800 TOF-TOF. ESIMS data were acquired on a Waters Micromass LCT Classic mass spectrometer and Varian 500-MS LC ion trap. HPLC separations were performed using Waters 510 HPLC pumps, a Waters 717 plus autosampler, and a Waters 996 photodiode array detector. All solvents were purchased as HPLC grade.

Extraction and Isolation Procedures

Cell Culturing

Axenic cultures of Phaeodactylum tricornutum Bohlin clone Pt1 8.6 (CC-MP2561) were obtained from the culture collection of the Provasoli-Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, West Boothbay Harbor, ME. Cultures were grown in f/2 medium43 made from 0.2 μm filtered, autoclaved seawater supplemented with filter-sterilized vitamins and inorganic nutrients. Cultures were incubated at 18 °C under constant light (100 μmol m−2 s−1). Sterility was monitored by occasional inoculation into peptone-enriched media to check for bacterial growth.44 Diatom cells were harvested by centrifugation for 15 min at 4000g, and pellets were frozen instantly in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C before further workup in the laboratory at the Marine Biotechnology Center, Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers University.

The material (40 g) was extracted three times with MeOH to give a polar crude organic extract (420 mg). A portion of this extract (15 mg) was tested for apoptosis induction. The crude organic extract was found active and subjected to fractionation using a solid-phase extraction cartridge (normal-phase silica) to give four fractions, F1 to F4, using hexane, CH2Cl2, EtOAc, and MeOH as an increasingly hydrophilic solvent system series. The fraction eluting with EtOAc (F3) had apoptosis induction activity. This fraction was further chromatographed on analytical RP HPLC (Phenomenex luna C18, 250 × 4.60 mm) using isocratic elution with 100% MeOH (flow rate 1 mL/min) to yield successively 5 mg of 2 (tR = 5.65 mn) and 10 mg of 1 (tR = 6.45 min).

Acid and Base Hydrolysis

Compound 1 (7.5 mg) was dissolved in MeOH (1.5 mL), and NaOMe (2.5 mg) was added; the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with the acidic ion-exchange resin Amberlite IRC-50 (Rohm and Hass, H+ form), with the resin removed by filtration. The filtrate was dried under reduced pressure and partitioned between CHCl3 and H2O. The organic layer was analyzed by GC-MS. The aqueous layer of compound 1 was purified and analyzed, then treated with 2 N HCl (2.5 mL) and refluxed for 30 min. The reaction mixture was processed and the sugar fraction isolated on an activated carbon column to give β-D-galactose (0.9 mg), identified by comparison with an authentic sample (TLC) and by its optical rotation ([α]26D +52.8 in H2O).

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Compounds 1 and 2 (2 mg) were separately dissolved in 4 mL of dioxane–H2O (1:1) and treated with lipase enzyme type III (2 mg, 50 unit, from a Pseudomonas species, Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C, with shaking for 4 h. The reaction mixtures of compounds 1 and 2 were quenched with 5% AcOH (1 mL), and the product was dried under reduced pressure. The crude residues of compounds 1 and 2 were dissolved in H2O and extracted with EtOAc, concentrated under reduced pressure, and analyzed by ESIMS.

Biological Evaluation: Apoptosis Induction

Apoptosis induction in the presence of compounds 1 and 2 was carried out as described in ref 11 using the ApopScreen assay.12 Viability of W2 (apoptosis competent) and D3 (apoptosis defective) cells was measured using a modification of the MTT assay.26 Differential growth from time 0 to 48 h was calculated. Starurosporine, an apoptosis inducer, and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Compound 1

[α]26D −4.0 (c 0.4, CHCl3); IR νmax (neat) 3400, 1740 cm−1; 1H NMR and 13C NMR, see Table 1; HR MALDI-TOFMS m/z 793.4883 (M + Na)+ (calcd for C45H70O10Na, 793.4867).

Compound 3

[α]25D −9.0 (c 0.2, H2O); 1H NMR (500 MHz, C5D5N) δH 4.13 (2H, d, J = 5.5 Hz, H-1a, H-1b), 4.47 (1H, m, H-2), 4.25 (1H, dd, J = 9.6, 3.9 Hz, H-3b), 4.92 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, H-1′), 4.52 (1H, dd, J = 9.4, 7.5 Hz, H-2′), 4.16 (1H, dd, J = 9.4, 3.1 Hz, H-3′), 4.55 (1H, d, J = 3.5 Hz, H-4′), 4.08 (1H, dd, J = 6.4, 5.6 Hz, H-5′), 4.42 (3H, m, H-6′a, H-6′b, H-3a).

Supplementary Material

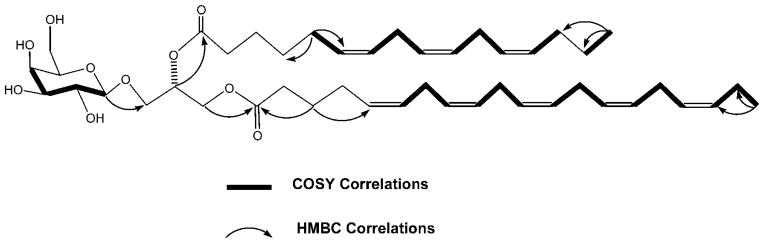

Figure 1.

Key HMBC and selected COSY correlations for compound 1.

Figure 2.

Compounds 3, 4, and 5 resulting from chemical degradation of 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. McPhail for NMR data from NMR facilities at Oregon State University. We also thank H. Zheng for mass spectrometry analyses at the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine, Rutgers University. We acknowledge A. De Martino from Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France, for providing the diatom image. This research was funded by Rutgers University through an Academic Excellence award and by the NIH (R37 CA53370 to E.W.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: 1H NMR, 13C NMR, 1H-1H COSY, multiplicity-edited HSQC, HMBC, and MS data of compound 1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Wichard T, Pohnert G. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7114–7115. doi: 10.1021/ja057942u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenoci L, Camp PJ. Langmuir. 2008;24:217–223. doi: 10.1021/la702278f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixit SS, Smol JP, Kingston JC, Charles DF. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrianasolo EH, France D, Cornell-Kennon S, Gerwick WH. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:576–579. doi: 10.1021/np0503956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crews P, Gerwick W, Schmitz F, France D, Bair K, Wright A, Hallock Y. Pharmaceut Biol. 2005;41(Suppl 1):39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams J. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2418–2495. doi: 10.1101/gad.1126903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danial N, Korsmeyer S. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelinas C, White E. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1263–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.1326205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degenhardt K, White E. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5274–5276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fesik SW. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:876–885. doi: 10.1038/nrc1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrianasolo EH, Haramaty L, Degenhardt K, Mathew R, White E, Lutz R, Falkowski P. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1551–1557. doi: 10.1021/np070088v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew R, Degenhart K, Haramaty L, Karp CM, White E. Methods Enzymol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01605-4. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. In: Progammed Cell Death. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, editors. Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 2008. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii T, Okino T, Mino Y. J Nat Prod. 2006;69:1080–1082. doi: 10.1021/np050530e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scribe P, Guezennec J, Dagaut J, Pepe C, Saliot A. Anal Chem. 1988;60:928–931. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa I, Hayashi K, Kobayashi M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1989;37:849–851. doi: 10.1248/cpb.37.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reshef V, Mizrachi E, Maretzki T, Silberstein C, Loya S, Hizi A, Carmeli S. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:1251–1260. doi: 10.1021/np970327m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshima Y, Yamada S, Matsunaga K, Moriya T, Ohizumi Y. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:534–536. doi: 10.1021/np50106a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen E, Kharazmi A, Christensen LP, Christensen SB. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:994–995. doi: 10.1021/np0300636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi K, Ono S. J Biochem. 1973;73:763–770. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a130139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Fadhi A, Wahidulla S, D’Souza L. Glycobiology Advance Access. 2006:22. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guella G, Frassanito R, Mancini I. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:1982–1994. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutignano A, d’Ippolito G, Romano G, Lamari N, Cimino G, Febbraio F, Nucci R, Fontana A. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:450–456. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.d’Ippolito G, Tucci ST, Cutignano A, Romano G, Cimino G, Miralto A, Fontana A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1686:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraga Y, Kaku K, Omoda D, Sugihara K, Hosoya H, Hino M. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:1494–1496. doi: 10.1021/np0201265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosmann T. J Immunol Meth. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergsson G, Arnfinnsson J, Steingrimsson O, Thormar H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3209–3212. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3209-3212.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams DE, Sturgeon CM, Roberge M, Andersen RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5822–5823. doi: 10.1021/ja0715187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morimoto T, Nagatsu A, Murakami N, Sakakibara J, Tokuda H, Nishimo H, Iwashima A. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:1433–1437. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00458-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P, Yadav DK, Siripurapu KB, Palit G, Maurya R. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:1410–1416. doi: 10.1021/np0700164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pohnert G. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:103–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.010974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miralto A, Barone G, Romano G, Poulet SA, Ianora A, Russo GL, Buttino I, Mazzarella G, Laabir M, Cabrini M, Giacobbe M. Nature. 1999;402:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pohnert G. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:4352–4356. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001201)39:23<4352::AID-ANIE4352>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ianora A, Miralto A, Poulet SA, Carotenuto Y, Buttino I, Romano G, Casotti R, Pohnert G, Wichard T, Colucci-D’Amato L, Terrazzano G, Smetacek V. Nature. 2004;429:403–407. doi: 10.1038/nature02526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fontana A, d’Ippolito G, Cutignano A, Romano G, Lamari N, Gallucci Massa A, Cimino G, Miralto A, Ianora A. Chem Bio Chem. 2007;8:1810–1818. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.d’Ippolito G, Romano G, Caruso T, Spinella A, Cimino G, Fontana A. Org Lett. 2003;5:885–887. doi: 10.1021/ol034057c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barofsky A, Pohnert G. Org Lett. 2007;9:1017–1012. doi: 10.1021/ol063051v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colombo D, Compostella F, Ronchetti F, Scala A, Toma L, Mukainaka T, Nagatsu A, Konoshima T, Tokuda H, Nishino H. Cancer Lett. 1999;143:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colombo D, Scala A, Taino IM, Toma L, Ronchetti F, Tokuda H, Nishino H, Nagatsu A, Sakakibara J. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1996;6:1187–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colombo D, Compostella F, Ronchetti F, Scala A, Toma L, Tokuda H, Nishino H. Eur J Med Chem. 2000;35:1109–1113. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)01193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vardi A, Formiggini F, Casotti R, De Martino A, Ribalet F, Miralto A, Bowler C. Plos Biol. 2006;4:411–419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siaut M, Heijde M, Mangogna M, Montsant A, Coesel S, Allen A, Manfredonia A, Falciatore A, Bowler C. Gene. 2007;406:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillard RRL, Kilham P. In: The Biology of Diatoms. Werner D, editor. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1978. pp. 372–464. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen RA, Morton SL, Sexton JP. J Phycol. 1997;33:6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.