Abstract

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) is responsible for activating the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel by first sensing the changes in Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum ([Ca2+]ER) via its luminal canonical EF-hand motif and subsequently oligomerizing to interact with the CRAC channel pore-forming subunit Orai1. In this work, we applied a grafting approach to obtain the intrinsic metal-binding affinity of the isolated EF-hand of STIM1, and further investigated its oligomeric state using pulsed-field gradient NMR and size-exclusion chromatography. The canonical EF-hand bound Ca2+ with a dissociation constant at a level comparable with [Ca2+]ER (512 ± 15 μM). The binding of Ca2+ resulted in a more compact conformation of the engineered protein. Our results also showed that D to A mutations at Ca2+-coordinating loop positions 1 and 3 of the EF-hand from STIM1 led to a 15-fold decrease in the metal-binding affinity, which explains why this mutant was insensitive to changes in Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum ([Ca2+]ER) and resulted in constitutive punctae formation and Ca2+ influx. In addition, the grafted single EF-hand motif formed a dimer regardless of the presence of Ca2+, which conforms to the EF-hand paring paradigm. These data indicate that the STIM1 canonical EF-hand motif tends to dimerize for functionality in solution and is responsible for sensing changes in [Ca2+]ER.

Keywords: affinity, Ca2+, EF-hand, oligomerization, STIM1

Introduction

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), recently identified by RNA interference (RNAi) screens in Drosophila S2 cells and HeLa cells by two independent groups [1,2], is regarded as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) luminal Ca2+ sensor and functions as an essential component of store-operated Ca2+ entry. It is a key linkage between ER Ca2+ store emptying, Ca2+ influx and internal Ca2+ store refilling in mammalian cells. On ER Ca2+ store depletion, STIM1 undergoes oligomerization, translocates from the ER membrane to form ‘punctae’ near the plasma membrane [1,3,4] and activates the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel through direct interaction with the pore-forming subunit Orai1 [5]. STIM1 is a single transmembrane- spanning protein with 685 amino acids which contains a canonical EF-hand motif and a sterile α-motif (SAM) domain in the ER lumen. Previous studies have strongly indicated that the EF-hand region is responsible for the sensing by STIM1 of the changes in [Ca2+]ER. Mutations on the predicted EF-hand reduce the affinity for Ca2+, thus mimicking the store-depleted state and subsequently triggering STIM1 redistribution to the plasma membrane and activation of the CRAC channel even without Ca2+ store depletion [4,6]. However, the site-specific metal-binding property and the oligomeric state of the canonical EF-hand of STIM1 alone have not been characterized thus far.

The EF-hand motif with a characteristic helix–loop–helix fold was first discovered by Moews and Kretsinger [7] in the crystal structure of parvalbumin. To date, more than 66 members of EF-hand proteins have been classified [8]. EF-hand proteins often occur in pairs with the two Ca2+-binding loops coupled via a short antiparallel β-sheet. Ca2+ is coordinated by the main-chain carbonyl and side-chain carboxyl oxygens at the 12- or 14-residue loop. One pair of EF-hands usually forms a globular domain to allow for cooperative Ca2+ binding, responding to a narrow range of free Ca2+ concentration change. To examine the key determinants for Ca2+ binding and Ca2+-induced conformational change, peptides or fragments encompassing the helix–loop–helix motif have been produced by either synthesis or cleavage. Shaw et al. [9] first reported that an isolated EF-hand III from skeletal troponin C dimerizes in the presence of Ca2+. EF-hands from parvalbumin and calbindin D9K have also been shown to exhibit Ca2+-dependent dimerization [10–12]. Wojcik et al. [13] have shown that the isolated 12-residue peptide from calmodulin (CaM) EF-hand motif III does not dimerize in the presence of Ca2+, but dimerizes to form a native-like structure in the presence of Ln3+, which has a similar ionic radius and coordination properties to Ca2+. They concluded that local interactions between the EF-hand Ca2+-binding loops alone could be responsible for the observed cooperativity of Ca2+ binding to EF-hand protein domains. Our laboratory has developed a grafting approach to probe the site-specific Ca2+-binding affinities and metal-binding properties of CaM [14] and other EF-hand proteins, such as the nonstructural protease domain of rubella virus [15]. We have shown that an isolated EF-hand loop without flanking helices grafted in CD2 remains as a monomer instead of a dimer, as observed in the peptide fragments [16], implying that additional factors that reside outside of EF-loop III may contribute to the pairing of the EF-hand motifs of CaM. Figure 1A shows that most hydrophobic residues in the flanking helices and loop are conserved compared with EF-hand III in CaM and the STIM1 EF-hand, such as position 8 in the loop, −8, −5, −1 in the E helix and +4, +5 in the F helix, which leads us to speculate that the EF-hand motif of STIM1 has the potential to form a dimer. In this work, we applied a grafting approach [14] to obtain the site-specific intrinsic metal-binding affinity and to probe the oligomeric state of the EF-hand of STIM1 using size-exclusion chromatography and pulsed-field diffusion NMR. We found that mutations on loop positions 1 and 3 of the EF-hand from STIM1 decreased the binding affinity by more than 10-fold. Interestingly, the isolated EF-hand motif of STIM1 undergoes Ca2+-induced conformational changes and remains as a dimer in the absence and presence of Ca2+.

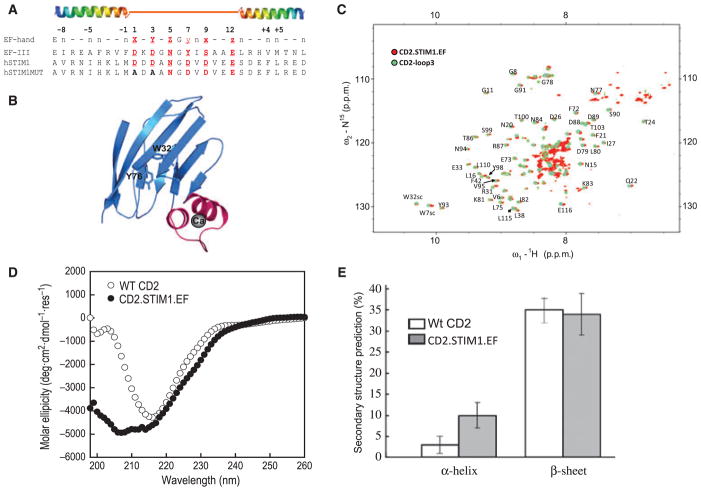

Fig. 1.

Grafting the helix–loop–helix EF-hand motif into CD2. (A) The sequence alignment results of calmodulin EF-hand III and the canonical EF-hand motif in STIM and its mutant. The sequence from S64 to L96 in STIM1 was grafted into CD2.D1. A mutant containing Asp to Ala substitutions at Ca2+-coordinating loop positions 1 and 3 was introduced to perturb the Ca2+-binding ability of the grafted EF-hand of STIM1. (B) Modelled structure of the engineered protein with the grafted EF-hand Ca2+-binding motif (magenta) from STIM1. W32 and Y76 in the host protein are about 15 Å away from the grafted Ca2+-binding sites. Ca2+ is shown as a dark sphere. (C) Overlay of the (1H, 15N)-HSQC spectrum of CD2.STIM1.EF (red) with that of CD2-loop3 (EF-loop III from calmodulin, cyan) in the absence of Ca2+. (D, E) Far-UV CD spectra of CD2 and CD2.STIM1.EF and the calculated secondary structural contents.

Results and Discussion

The isolated EF-hand motif from STIM1 retains its helical structure

The helix–loop–helix EF-hand motif from STIM1 was grafted into CD2 with each side flanked by three Gly residues to render sufficient flexibility (Fig. 1A). Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that the loop position in domain 1 of CD2 at 52 between the β-strands C″ and D tolerates the insertion of foreign EF-hand motifs from CaM whilst retaining its own structural integrity [15,17]. In Fig. 1B, the modelled structure of the engineered protein CD2.STIM1.EF is shown. The structural integrity of the host protein was then examined by two-dimensional NMR. As shown in Fig. 1C, the dispersed region of the (1H, 15N)-heteronuclear single-quantum correlation (HSQC) NMR spectrum of CD2.STIM1.EF was very similar to that of CD2 with grafted EF-loop III of CaM (CD2.CaM.loopIII) [16], suggesting that the conformation of the host protein CD2 is largely unchanged. Additional resonances appearing between 8.2 and 8.8 p.p.m. were caused by the addition of flanking helices to the grafted EF-hand motif.

To confirm that the grafted EF-hand motif retains its helical structure, CD spectra of the host protein CD2 domain 1 (CD2.D1) and CD2.STIM1.EF were analysed by DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses [18]. Figure 1D, E shows the far-UV CD spectra and the calculated secondary structure contents of both proteins. The host protein CD2.D1 contained 3% α-helix and 35% β-strand, which is in good agreement with the secondary structure contents determined by X-ray crystallography [19]. Following the insertion of the EF-hand motif from STIM1, the helical content increased by 7%, which corresponds to approximately 10 residues in the helical conformation, whereas the β-strand content largely remained similar to CD2.D1 (Fig. 1E).

The isolated EF-hand binds to Ca2+ and lanthanide ions

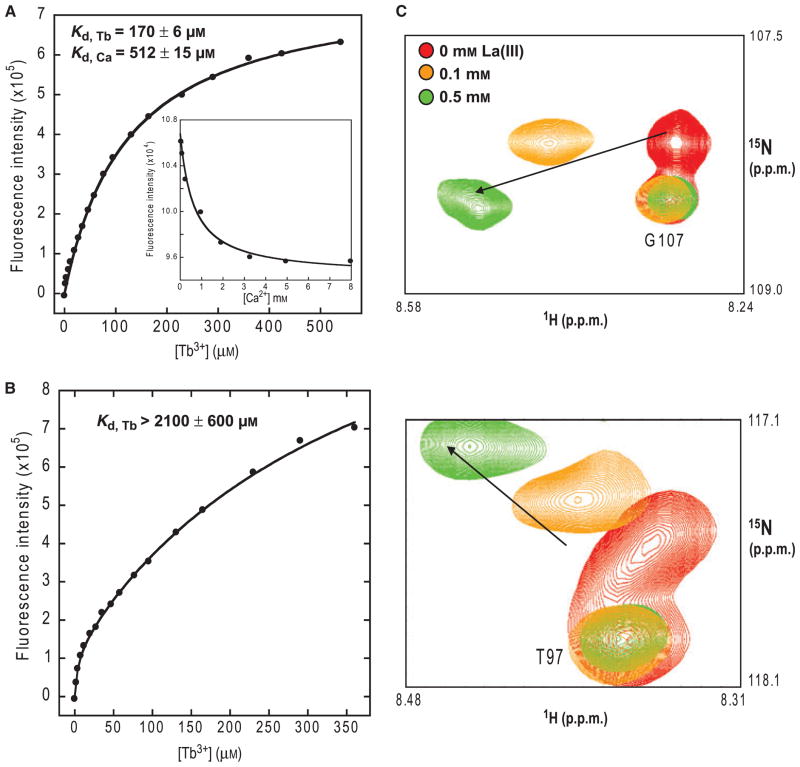

One of the most important steps to fully understand the mechanism underlying the Ca2+-modulated functions of STIM1 is to investigate the site-specific Ca2+-binding properties of the EF-hand of STIM1. In this study, we adopted a grafting approach to address this question. As shown in Fig. 1B, the distance between the two termini of the inserted Ca2+-binding sites in the model structure of the EF-hand of STIM1 is within 15 Å. Accordingly, a total of six glycine linkers is sufficient to enable the grafted motifs to retain the native metal conformation. Trp32 and Tyr76 in the host proteins are approximately 15 Å away from the grafted sites, which enables aromatic-sensitized energy transfer to the Tb3+ bound to the sites, providing a sensitive spectroscopic method to monitor the metal-binding process. As shown in Fig. 2A, the addition of Tb3+ to the engineered proteins, or vice versa, resulted in large increases in Tb3+ fluorescence at 545 nm caused by energy transfer, which was not observed for wild-type CD2.D1 [15,20]. The addition of excessive amounts of Ca2+ to the Tb3+–protein mixture led to a significant decrease in Tb3+ luminescence signal as a result of metal competition (Fig. 2A, inset). The Tb3+- and Ca2+-binding affinities could thus be derived from the Tb3+ titration and metal competition curves. For the engineered protein CD2.STIM1.EF, the Tb3+- and Ca2+-binding dissociation constants (Kd) were 170 ± 6 and 512 ± 15 μM, respectively. In contrast, a mutant with the metal-coordinating residue Asp at positions 1 and 3 in the EF-loop substituted with Ala (denoted as CD2.STIM1mut) resulted in at least a 12-fold decrease in the Tb3+-binding affinity (Kd > 2.1 mM, Fig. 2B), suggesting that these key residues are essential for metal binding. The direct binding of metal ions to the grafted sequences was further supported by two-dimensional HSQC NMR studies. As shown in Fig. 2C, the addition of increasing amounts of La3+, a commonly used trivalent Ca2+ analogue, led to gradual chemical shift changes in residues from the grafted sequences. However, residues from the host protein CD2.D1, such as T97 ad G107, remained unchanged.

Fig. 2.

Metal-binding properties of CD2.STIM1.EF. (A) The enhancement of Tb3+ luminescence at 545 nm plotted as a function of total added [Tb3+]. The inset shows the Ca2+ competition curve. (B) The enhancement of fluorescence at 545 nm of the CD2.STIM1.EF mutant (Asp to Ala substitutions at loop positions 1 and 3) as a function of titrated Tb3+. (C) Enlarged areas of (1H, 15N)-HSQC spectrum of CD2.STIM1. EF. La3+ induced chemical shift changes (indicated by arrows) in two residues from the grafted sequences. In contrast, the chemical shifts of residues from the host protein CD2.D1 (i.e. G107 and T97) remained unchanged.

The isolated EF-hand from STIM1 forms dimer in solution

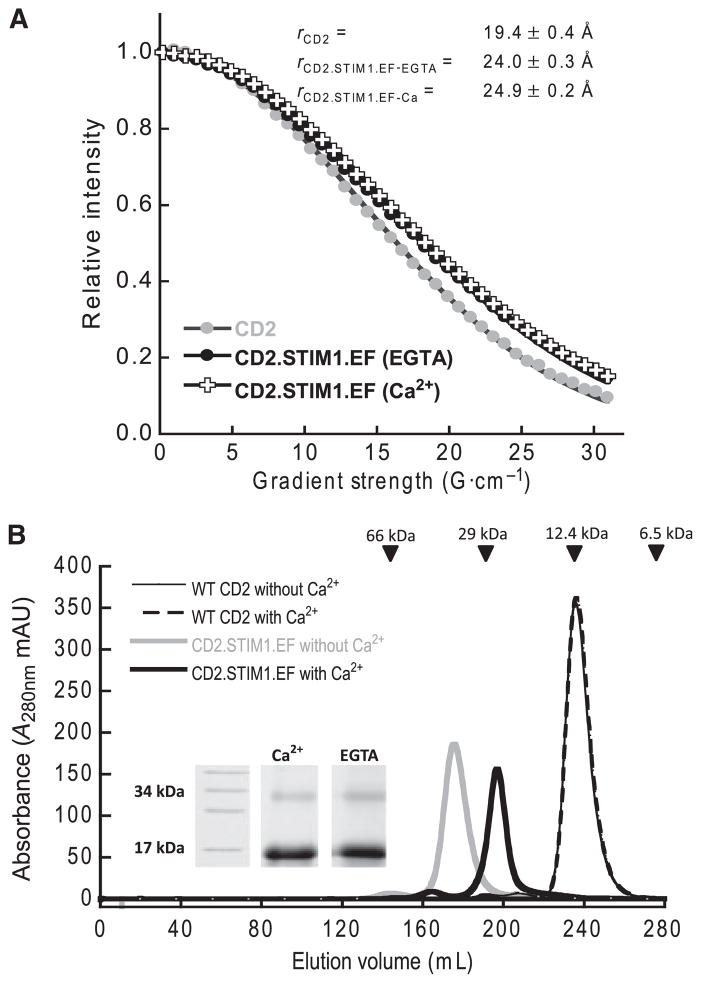

Next, we examined the oligomeric state of the grafted EF-hand motif using three independent techniques: pulsed-field gradient NMR, size-exclusion chromatography and chemical cross-linking. Pulsed-field gradient NMR has been widely used to study the molecular motion, effective dimensions and oligomeric states of proteins in solution [21]. With this technique, the size of proteins can be estimated by measuring diffusion constants, as the relationship between the translational motion of spherical molecules in solution and the hydrodynamic radius is governed by the equation, D = KBT/6πaη, where η is the solvent viscosity and a is the radius of the molecules. The diffusion constant of a dimer is ideally expected to be approximately 79% of the value of a monomer [21].

The diffusion constants of engineered protein CD2.STIM1.EF were measured under Ca2+-depleted and Ca2+-saturated conditions to determine whether the isolated EF-hand motif from STIM1 undergoes dimerization on metal binding. Figure 3A shows the NMR signal decay when the field strength was increased from 0.2 to 31 G·cm−1. The calculated hydrodynamic radius of the CD2 monomer was 19.4 ± 0.4 Å, which was close to the previously reported value of 19.6 Å [16]. The calculated hydrodynamic radii of the engineered protein CD2.STIM1. EF were 24.0 ± 0.3 Å with 10 mM EGTA and 24.9 ± 0.2 Å with 10 mM Ca2+. According to calculations using the spherical shape of macromolecules, the hydrodynamic radius of the protein will increase by 27% on formation of the dimer [22]. The increase in size for CD2.STIM1.EF is very close to this theoretical value, indicating that it exists as a dimer in solution, regardless of the presence of Ca2+.

Fig. 3.

The oligomeric state of CD2.STIM1.EF. (A) The NMR signal decay of CD2 (grey circles) and CD2.STIM1.EF with Ca2+ (crosses) or EGTA (filled circles) as a function of field strength. The calculated hydrodynamic radii of the protein samples are indicated. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles of CD2 (thin lines) and CD2.STIM1.EF (bold lines) in the presence of 10 mM Ca2+ or EGTA. The protein molecular mass standards are indicated by arrows. Inset: SDS-PAGE of cross-linked CD2.STIM1.EF in the presence of 5 mM EGTA or Ca2+.

Size-exclusion chromatography was also used to estimate the size of the engineered protein under Ca2+-saturated and Ca2+-free conditions. As shown in Fig. 3B, the elution profiles of 10 mM Ca2+-loaded and Ca2+-depleted CD2.STIM1.EF exhibited a major peak, with estimated molecular masses of 28 and 32 kDa, respectively, which is close to twice the theoretical molecular mass of CD2.STIM1.EF. However, the Ca2+-loaded CD2.STIM1.EF was eluted slightly later than the Ca2+-depleted form. This shift in peak position suggests that Ca2+-loaded CD2.STIM1.EF has a smaller size than Ca2+-depleted CD2.STIM1.EF. It seems that Ca2+ induced conformational changes in the engineered protein and resulted in a more compact shape of the protein.

One additional method, glutaraldehyde cross-linking, was applied to study the oligomerization patterns of the engineered protein at low micromolar concentration. Figure 3B (inset) shows SDS-PAGE of glutaraldehyde- mediated cross-linking of CD2.STIM1.EF (20 μM) in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ or 5 mM EGTA. Regardless of the presence of Ca2+, bands corresponding to both monomeric and dimeric CD2. STIM1.EF were observed on SDS-PAGE. In summary, our data suggest that the grafted EF-hand motif from STIM1 tends to dimerize in solution.

Implications for Ca2+-binding properties of STIM1

Previous studies have demonstrated that STIM1 plays an important role in store-operated Ca2+ entry [3]. On store depletion, STIM1 is redistributed from the ER membrane to form ‘punctae’ and aggregates near the plasma membrane [1,6]. The N-terminal region of STIM1 contains a canonical EF-hand motif and a predicted SAM domain. Stathopulos et al. [23,24] isolated the EF-SAM region from STIM1 and studied the structural and biophysical properties on this domain after refolding. Their excellent work indicated that the ER Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of STIM1 occurs via the EF-SAM region. However, the refolding process may not guarantee the natural conformation of the EF-SAM region. Furthermore, as both the EF-hand motif and the SAM region have the potential to facilitate oligomerization, it is challenging to differentiate which region contributes to the oligomerization process.

To overcome the limitations of investigating the Ca2+-binding sites in native Ca2+-binding proteins, we established a grafting approach to dissect their site-specific properties. This approach has been used in the investigation of single EF-hand motifs in CaM and a single EF-hand from rubella virus nonstructural protease [14,15]. CD2 has been shown to be a suitable host system, as it retains its native structure after the insertion of foreign sequences and in the presence and absence of Ca2+ ions, so that the influence from the host protein to the inserted sites is minimized [14]. Our NMR spectra shown in Fig. 2A clearly demonstrate that the conformation of CD2 is unchanged. After the insertion of the helix–loop–helix EF-hand domain from STIM1, the helical content of the engineered protein CD2.STIM1.EF increased, indicating that the inserted EF-hand motif at least partially maintains the natural helical structure after grafting. The Ca2+ dissociation constant of CD2.STIM1.EF (512 μM) is in good agreement with the previously reported value (200–600 μM) [25] and is comparable with [Ca2+]ER (250–600 μm) [15,26]. Such dissociation constants would ensure that at least one-half of the population of the EF-hand motif in STIM1 is occupied by Ca2+. Removing the proposed Ca2+-coordinating residues in positions 1 and 3 of the EF-hand motif significantly compromised the metal-binding capability of the engineered protein, indicating that the metal binding of CD2.STIM1.EF is through the EF-hand motif from STIM1. Two-dimensional HSQC NMR studies further corroborated this view, as only residues from the grafted sequences underwent chemical shift changes, whereas residues from the host protein remained unchanged. The impaired metal-binding ability caused by Asp to Ala mutations at positions 1 and 3 echoed a previous observation that these mutations in the intact STIM1 molecule led to constitutive activation of CRAC channels even without store depletion [4].

The canonical EF-hand in STIM1 has been regarded previously to function alone to sense Ca2+ changes. The recently determined structure of the EF-SAM region of STIM1 unveiled a surprising finding [24]. Immediately next to the single canonical EF-hand, there is a ‘hidden’, atypical, non-Ca2+-binding EF-hand motif that stabilizes the intramolecular interaction between the canonical EF-hand and the SAM domain. This hidden EF-hand pairs with the upstream canonical EF-hand through hydrogen bonding between residues at corresponding loop position 8 (V83 and I115). Indeed, our results suggest that the isolated canonical EF-hand alone has an intrinsic tendency to form a dimer, which is in agreement with the EF-hand pairing paradigm. Clearly, the canonical EF-hand motif alone is able to sense the ER Ca2+ concentration changes. Previous studies have indicated that the Ca2+ depletion-induced conformational change of the EF-SAM region promotes a monomer to oligomer transition [25]. Our data also suggest that the EF-hand alone has a tendency to form dimers in solution and undergoes Ca2+-induced conformational changes by forming a more compact shape. Thus, the [Ca2+] changes in the ER lumen are sensed by the canonical EF-hand motif and cause conformational changes in this motif. The Ca2+ signal change and the accompanying conformational change in the canonical EF-hand are probably relayed to the SAM domain via the paired ‘hidden’ EF-hand, resulting in the oligomerization of STIM1 on store depletion.

To date, more than 3000 EF-hand proteins have been reported in various organisms, including prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems [27]. For example, in bacteria, about 500 EF-hand motifs were predicted using developed bioinformatics tools [27]. Many of the predicted EF-hand proteins are membrane proteins like STIM1. The determined Ca2+-binding affinity and dimerization properties of STIM1 in this study suggest that our developed grafting approach can be widely applied to probe site-specific metal binding and oligomerization properties of other predicted EF-hand proteins, overcoming the limitation associated with membrane proteins and the difficulties encountered in crystallography. In addition, such information is useful to further develop predicative tools for predicting the role of Ca2+ and Ca2+-binding proteins in biological systems.

Materials and methods

Molecular cloning and modelling of engineered CD2.STIM1.EF

The single EF-hand motif in STIM1 (SFEAVRNIH-KLMDDDANGDVDVEESDEFLREDL, proposed Ca2+- coordinating ligands in italic) was inserted into the host protein CD2 domain 1 between residues S52 and G53 with three Gly at the N-terminus and two at the C-terminus (denoted as CD2.STIM1.EF) following previous protocols [14]. Site-directed mutagenesis at STIM1 was performed using a standard PCR method. All sequences were verified by automated sequencing on an ABI PRISM-377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in the Advanced Biotechnology Core Facilities of Georgia State University. Structural modelling of CD2.STIM1.EF was performed using MODELLER9V2 [28] based on the crystal structures of CD2 domain 1 (pdb entry: 1hng) [29] and the EF-hand from the EF-SAM region of STIM1 (pdb entry: 2k60) [24].

Protein expression and purification

The engineered protein CD2.STIM1.EF was expressed as a glutathione transferase (GST) fusion protein in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells in Luria–Bertani medium with 100 mg·L−1 of ampicillin at 37 °C. For 15N isotopic labelling, 15NH4Cl was supplemented as the sole source for nitrogen in the minimal medium. The expression of protein was induced for 3–4 h by adding 100 μM of isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG) when the absorbance at 600 nm (A600) reached 0.6. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 5000 g for 30 min. The purification procedures followed the protocols for GST fusion protein purification using glutathione Sepharose 4B beads, as described previously [14,15,20]. The GST tag of the proteins was removed from the beads by thrombin. The eluted proteins were further purified using gel filtration (Superdex 75) and cation-exchange (Hitrap SP columns, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) chromatography. The protein concentrations were determined using ε280 = 11 700 M−1·cm−1 [30].

CD spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra (190–260 nm) were acquired using a Jasco-810 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Easton, MD, USA) at ambient temperature. A 20 μM sample was placed in a 1 mm path length quartz cell in 10 mM Tris/HCl at pH 7.4. All spectra were the average of at least 10 scans with a scan rate of 50 nm·min−1. The spectra were converted to the mean residue molar ellipticity (deg·cm2·dmol−1·per residue) after subtracting the spectrum of buffer as the blank. The calculation of secondary structure elements was performed using DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses [18].

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Steady-state fluorescence was recorded using a PTI fluorimeter at 25 °C with a 1 cm path length cell. Intrinsic Trp emission spectra were recorded using 1.5–3.0 μM protein samples in 50 mM Tris–100 mM KCl at pH 7.4. The Trp fluorescence spectra were recorded from 300 to 400 nm with an excitation wavelength of 282 nm. The slit widths were set at 4 and 8 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. For Tyr/Trp-sensitized Tb3+ luminescence energy transfer experiments, emission spectra were collected from 500 to 600 nm with excitation at 282 nm, and the slit widths were set at 8 and 12 nm for excitation and emission, respectively. To circumvent secondary Raleigh scattering, a glass filter with a cut-off of 320 nm was used. The Tb3+ titration experiments were performed by gradually adding 5–10 μL aliquots of Tb3+ stock solutions (1 mm) to the protein samples (2.5 μM) in 20 mM Pipes, 100 mM KCl at pH 6.8 to prevent precipitation. For the Ca2+ competition studies, the solution containing 30 μM of Tb3+ and 1.5 μM of protein was set as the starting point. The stock solution of 10–100 mM CaCl2 with the same concentration of Tb3+ and protein was gradually added to the initial mixture. The fluorescence intensity was normalized by subtracting the contribution of the baseline slope using logarithmic fitting. The Tb3+-binding affinity of the protein was obtained by fitting normalized fluorescence intensity data using the equation:

| (1) |

where f is the fractional change, Kd is the dissociation constant for Tb3+, and [P]T and [M]T are the total concentrations of protein and Tb3+, respectively. The Ca2+ competition data were first analysed to derive the apparent dissociation constant by Eqn (1). By assuming that the sample is saturated with Tb3+ at the starting point of the competition, the Ca2+-binding affinity is further obtained using the equation:

| (2) |

where Kd, Ca and Kd, Tb are the dissociation constants of Ca2+ and Tb3+, respectively. Kapp is the apparent dissociation constant.

Size-exclusion chromatography

Size-exclusion chromatography was performed on a HiLoad Superdex 75 (26/65) column using an AKTA FPLC System (GE Healthcare) with a flow rate of 2.5 mL·min−1 at 4 °C. The EF-hand samples or molecular standards (Sigma MW-GF-70; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were eluted in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl with either 10 mM EGTA or 10 mM CaCl2.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were collected on a Varian 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Two-dimensional (1H, 15N)-HSQC spectra were collected with 4096 complex data points at the 1H dimension and 128 increments at the 15N dimension. Samples contained 0.5 mM of the protein in 10 mM Tris–100 mM KCl, 0–1 mM LaCl3, 10% D2O at pH 7.4. Pulsed-field gradient NMR diffusion experiments were performed as described previously [16]. In brief, 0.3 mM protein samples were prepared in a buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris, 100 mM KCl at pH 7.4 with either 10 mM CaCl2 or 10 mM EGTA. The spectra were collected using a modified pulse gradient stimulated echo longitudinal encode–decode pulse sequence [21] with 8000 complex data points for each free induction decay. The diffusion constants were obtained by fitting the corresponding integrated area of the resonances of the arrayed spectrum with the following equation:

| (3) |

where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio of the proton, δ is the pulsed-field gradient duration time (5 ms) and Δ is the duration between two pulsed-field gradient pulses (112.5 ms). The gradient strength (G) was arrayed from 0.2 to approximately 31 G·cm−1 using 40 steps. The diffusion constant D was obtained by fitting the data using a zero-order polynomial function with R2 > 0.999. NMR diffusion data for lysozyme in identical buffer conditions were collected, with a hydrodynamic radius of 20.1 Å used as standard [16]. All the NMR data were processed using FELIX (Accelrys, San Diego, CA, USA) on a Silicon Graphics computer.

Protein cross-linking with glutaraldehyde

The reaction mixture contained 100 μg protein, 20 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.5) and 0.2% (w/v) glutaraldehyde (Sigma). The mixtures were reacted at 37 °C for 10 min and stopped by SDS-PAGE loading buffer, which contains 50 mM Tris/HCl, followed by boiling for 10 min. Cross-linked proteins were then resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dan Adams and Michael Kirberger for critical review of the manuscript and helpful discussions, Drs Hsiau-wei Lee and Wei Yang for their help in the NMR diffusion study and Rong Fu for her help in the size-exclusion study. This work was supported in part by the following sponsors: NIH EB007268 to JJY, Brain and Behavior Predoctoral Fellowship to YH and Molecular Basis of Disease Predoctoral Fellowship to YZ.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]ER

Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum

- CaM

calmodulin

- CRAC

Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GST

glutathione transferase

- HSQC

heteronuclear single-quantum correlation

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SAM

sterile α-motif

- STIM1

stromal interaction molecule 1

References

- 1.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauser CT, Tsien RY. A hexahistidine-Zn2+- dye label reveals STIM1 surface exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3693–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611713104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 2005;437:902–905. doi: 10.1038/nature04147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF, Muallem S. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:337–343. doi: 10.1038/ncb1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spassova MA, Soboloff J, He LP, Xu W, Dziadek MA, Gill DL. STIM1 has a plasma membrane role in the activation of store-operated Ca(2+) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4040–4045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moews PC, Kretsinger RH. Refinement of the structure of carp muscle calcium-binding parvalbumin by model building and difference Fourier analysis. J Mol Biol. 1975;91:201–225. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawasaki H, Nakayama S, Kretsinger RH. Classification and evolution of EF-hand proteins. Biometals. 1998;11:277–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1009282307967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw GS, Hodges RS, Sykes BD. Determination of the solution structure of a synthetic two-site calcium- binding homodimeric protein domain by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9572–9580. doi: 10.1021/bi00155a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchini PL, Reid RE. Investigating site-specific effects of the -X glutamate in a parvalbumin CD site model peptide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;372:80–88. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini PL, Reid RE. A model for circular dichroism monitored dimerization and calcium binding in an EF-hand synthetic peptide. J Theor Biol. 1999;199:199–211. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1999.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Julenius K, Robblee J, Thulin E, Finn BE, Fairman R, Linse S. Coupling of ligand binding and dimerization of helix–loop–helix peptides: spectroscopic and sedimentation analyses of calbindin D9k EF-hands. Proteins. 2002;47:323–333. doi: 10.1002/prot.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojcik J, Goral J, Pawlowski K, Bierzynski A. Isolated calcium-binding loops of EF-hand proteins can dimerize to form a native-like structure. Biochemistry. 1997;36:680–687. doi: 10.1021/bi961821c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye Y, Lee HW, Yang W, Shealy S, Yang JJ. Probing site-specific calmodulin calcium and lanthanide affinity by grafting. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3743–3750. doi: 10.1021/ja042786x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Y, Tzeng WP, Yang W, Zhou Y, Ye Y, Lee HW, Frey TK, Yang J. Identification of a Ca2+- binding domain in the rubella virus nonstructural protease. J Virol. 2007;81:7517–7528. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00605-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HW, Yang W, Ye Y, Liu ZR, Glushka J, Yang JJ. Isolated EF-loop III of calmodulin in a scaffold protein remains unpaired in solution using pulsed-field-gradient NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1598:80–87. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(02)00338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Y, Lee HW, Yang W, Shealy SJ, Wilkins AL, Liu ZR, Torshin I, Harrison R, Wohlhueter R, Yang JJ. Metal binding affinity and structural properties of an isolated EF-loop in a scaffold protein. Protein Eng. 2001;14:1001–1013. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W668–W673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodian DL, Jones EY, Harlos K, Stuart DI, Davis SJ. Crystal structure of the extracellular region of the human cell adhesion molecule CD2 at 2.5 Å resolution. Structure. 1994;2:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y, Zhou Y, Yang W, Butters R, Lee HW, Li S, Castiblanco A, Brown EM, Yang JJ. Identification and dissection of Ca(2+)-binding sites in the extracellular domain of Ca(2+)-sensing receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19000–19010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701096200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkins DK, Grimshaw SB, Receveur V, Dobson CM, Jones JA, Smith LJ. Hydrodynamic radii of native and denatured proteins measured by pulse field gradient NMR techniques. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16424–16431. doi: 10.1021/bi991765q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altieri AS, Byrd RA. Randomization approach to water suppression in multidimensional NMR using pulsed field gradients. J Magn Reson B. 1995;107:260–266. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Ikura M. Stromal interaction molecule (STIM) 1 and STIM2 calcium sensing regions exhibit distinct unfolding and oligomerization kinetics. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:728–732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800178200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: an initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demaurex N, Frieden M. Measurements of the free luminal ER Ca(2+) concentration with targeted ‘cameleon’ fluorescent proteins. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou Y, Yang W, Michael K, Lee H-W, Ayalasomayajula G, Yang J. Prediction of EF-hand calcium binding proteins and analysis of bacterial EF-hand proteins. Proteins. 2006;65:643–655. doi: 10.1002/prot.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones EY, Davis SJ, Williams AF, Harlos K, Stuart DI. Crystal structure at 2.8 Å resolution of a soluble form of the cell adhesion molecule CD2. Nature. 1992;360:232–239. doi: 10.1038/360232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Driscoll PC, Cyster JG, Somoza C, Crawford DA, Howe P, Harvey TS, Kieffer B, Campbell ID, Williams AF. Structure–function studies of CD2 by n.m.r. and mutagenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:947–952. doi: 10.1042/bst0210947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]