Abstract

Background

Cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization is the current recommended therapy for acute cholecystitis. The rate of cholecystectomy and subsequent healthcare trajectory in elderly patients with acute cholecystitis has not been evaluated.

Study Design

We used 5% national Medicare sample claims data from 1996–2005 to identify a cohort of patients ≥66 requiring urgent/emergent admission for acute cholecystitis. We evaluated cholecystectomy rates on initial hospitalization, the factors independently predicting receipt of cholecystectomy, the factors predicting further gallstone-related complications, and 2-year survival in the cholecystectomy and no cholecystectomy group in univariate and multivariate models.

Results

29,818 Medicare beneficiaries were urgently/emergently admitted for acute cholecystitis from 1996–2005. The mean age was 77.7±7.3 years. 89% of patients were white and 58% were female. 25% of patients did not undergo cholecystectomy during the index admission. Lack of definitive therapy was associated with a 27% subsequent cholecystectomy rate and a 38% gallstone-related readmission rate over in the two years after discharge, while the readmission rate was only 4% in patients undergoing cholecystectomy (P<0.0001). No cholecystectomy on initial hospitalization was associated with worse 2-year survival (HR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.47 – 1.65) even after controlling for patient demographics and comorbidities. Readmissions lead to an additional $7,000 in Medicare payments per readmission.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that 25% of Medicare beneficiaries cholecystectomy was not performed on index admission, leading to readmissions in 38% of surviving patients. For patients requiring readmission, the number of open procedures was increased, and the additional Medicare payments were $7,000 per admission. Cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in elderly patients should be performed during initial hospitalization to prevent recurrent episodes of cholecystitis, multiple readmissions, higher readmission rates, and increased costs.

Keywords: Acute cholecystitis, common bile duct stones, cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone disease is the most costly digestive disease in the United States. Approximately 20 million people in the U.S. have gallstones leading to over one million hospitalizations, 700,000 operative procedures, and $5 billion dollars in cost annually.1, 2 Annually, 1–4% of patients with gallstones will develop complications including acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, and common bile duct stones.3–5

The prevalence of gallstones increases sharply with age. Fifteen percent of men and 24% of women have gallstones by age 70. By age 90, this increases to 24% and 35%, respectively.6 In addition, complications are more common in older patients, occurring in 50,000–150,000 women and 15,000–60,000 men aged 65 and older each year.7 The most common complication requiring intervention in elderly patients is acute cholecystitis.

Cholecystectomy is the only definitive therapy for acute cholecystitis and other gallstone-related complications. Both laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy have been shown to be safe in the setting of acute cholecystitis.8–18 Moreover, additional gallstone-related complications occur in 20–30% of patients following an initial episode of acute cholecystitis if definitive therapy is not performed.9, 11, 14, 19, 20 A Cochrane group comprehensive review of randomized controlled trials (1998–2003) evaluating cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis concluded that laparoscopic cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization was associated with reduced hospital stays and no difference in rates of conversion open cholecystectomy, morbidity, or mortality.21

Management of complicated gallstones presents a unique set of challenges in the elderly population including delayed presentation, significant comorbid illness, and increased morbidity associated with elective and emergent surgery.6, 20 Adherence to the recommendations for management of acute cholecystitis and the natural history following initial presentation of elderly patients with acute cholecystitis has not been systematically studied. Our study uses a 5% national Medicare sample to measure cholecystectomy rates during initial hospitalization in Medicare patients with acute cholecystitis and identifies factors associated with failure to receive definitive therapy. We evaluate the natural history of patients who do and do not undergo cholecystectomy at the time of initial presentation and determine the factors that predict further gallstone-related complications. Identifying those at risk to both not receive definitive therapy and have further gallstone-related complications will provide targets for interventions designed to optimize the care of patients with acute cholecystitis.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston approved this study.

Data Source

Medicare is the primary health insurer for 95% of the U.S. population aged 65 and older. All Medicare beneficiaries receive Part A (hospital) benefits and 95% of beneficiaries also subscribe to Part B (supplemental) coverage. The Medicare Claims Data System collects information on all services provided to Medicare beneficiaries covered under Parts A and B. The 5% national Medicare sample Research Identifiable Files (RIF) are created by selecting records of beneficiaries based on the last two digits of their Health Insurance Claim (HIC) number. Claims can be linked within or across files for individual beneficiaries using a unique identifier provided by the CMS. Medicare files used for this study included the Denominator file (demographics and eligibility), the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file (MEDPAR, includes all inpatient claims), the Physician/Supplier Standard Analytical File (includes claims from service providers, such as physicians, that are not facilities, and the Outpatient Standard Analytical File (includes claims from institutional outpatient providers such as hospital clinics).

Cohort Selection

5% national Medicare sample claims data were available from 1995–2007. Using claims data from 1996–2005 we identified a cohort of patients admitted to an acute care hospital with acute cholecystitis with or without common bile duct stones. Choosing patients from 1996–2005 enabled us to evaluate comorbidities in the year prior to initial hospitalization and to follow all patients two years after their initial hospitalization for complicated gallstones. Using the ICD-9-CM codes listed in Table 1, we identified all patients in the MEDPAR files with a primary diagnosis of acute cholecystitis with or without common bile duct stones.

Table 1.

ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes for Gallstone-Related Disease

| Description | ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Codes |

|---|---|

| Acute cholecystitis | |

| Calculus of gallbladder with acute cholecystitis | 574.0 (574.00, 574.01) |

| Calculus of gallbladder with other cholecystitis | 574.1 (574.10, 574.11) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 575.0 |

| Other cholecystitis (excludes 574.4, 574.8, 574.1) | 575.1 |

| Obstruction of gallbladder | 575.2 |

| Hydrops of gallbladder | 575.3 |

| Perforation of gallbladder | 575.4 |

| Common bile duct stones | |

| Calculus of bile duct with acute cholecystitis | 574.3 (573.20, 574.31) |

| Calculus of bile duct with other cholecystitis | 574.4 (574.40, 574.41) |

| Calculus of bile duct without mention of acute cholecystitis | 574.5 (574.50, 574.51) |

| Calculus of gallbladder and bile duct with acute cholecystitis | 574.6 (574.60, 574.61) |

| Calculus of gallbladder and bile duct with other cholecystitis | 574.7 (574.70, 574.71) |

| Calculus of gallbladder and bile duct with acute and chronic cholecystitis | 574.8 (574.80, 574.81) |

| Calculus of gallbladder and bile duct without cholecystitis | 574.9 (574.90, 574.91) |

All admissions for acute cholecystitis were identified in the MEDPAR files by a principal discharge diagnosis codes shown in Table 1. These admissions were further subdivided based on ICD-9-CM codes acute cholecystitis or acute cholecystitis with common bile duct stones, also shown in Table 1. Patients with gallstone pancreatitis, defined by and ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis code listed in Table 1 and any secondary diagnosis code of pancreatitis (577.0),22 were excluded.

After identification of individuals with the above diagnoses the following inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied: 1) patients ≥66 years of age, 2) patients admitted to acute care facilities only (exclude skilled nursing and long-term care facilities), 3) first hospitalization for each patient (defined as no admissions for the same diagnoses in the year prior), 4) patients enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B without HMO for 12 months before and 24 months after initial hospitalization, 5) urgent or emergent admissions only.

In the MEDPAR claims files, admissions are classified as elective, urgent, or emergent in a variable called “Type of Admission.” Any patient admission classified as elective was excluded. We also excluded the ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 574.2* (“calculus of gallbladder without mention of cholecystitis”) as this is often an indication of symptomatic biliary colic, but not acute cholecystitis.

Statistical Analysis: Initial Hospitalization

All statistical analysis was performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (Cary, N.C.). We identified the number of patients undergoing cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization. Cholecystectomy was identified using ICD-9-CM procedure codes 51.21, 51.22 (open) and 51.23 and 51.24 (laparoscopic) during the initial hospitalization. Summary statistics were performed for the overall cohort including demographics, in-hospital mortality, length of stay, Elixhauser comorbidities,23 type of admission (urgent vs. emergent), weekend admission (yes/no), diagnosis (acute cholecystitis vs. acute cholecystitis with CBD stones, Table 1), Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) areas, hospital size, size of medical service area, type of hospital, admitting physician (medicine, surgery, gastroenterology, or other), gastroenterology evaluation, and teaching hospital status (major, minor, none).

A univariate analysis was done to compare the above factors in patients who did and did not receive definitive therapy during initial hospitalization. Chi-square analysis was used to determine differences between categorical variables and t-test to determine differences between continuous variables. Significance was accepted at the P<0.05 level.

The admitting physician was determined by searching the physician/supplier files for evaluation and management codes for “first encounter by and admitting physician” (99221–99223) corresponding to within 24 hours of the date of admission in the MEDPAR file. The Medicare specialty codes were be used to determine the admitting physician specialty, with specialty codes 01 (General Practice), 08 (Family Practice), 11 (Internal Medicine), and 38 (Geriatrics) classified as internal medicine/geriatrics, 02 (General Surgeon) classified as general surgeon, 10 (Gastroenterologist) classified as gastroenterology. Any other specialty was classified as other. If a patient was admitted to a gastroenterologist or had an evaluation and management bill for consultation (99251–99255) by a physician with a corresponding specialty code of 10, he or she was be considered as having been evaluated by a gastroenterologist.

We used the Elixhauser index measures the effect of patient comorbidities on the receipt of cholecystectomy and subsequent healthcare trajectory. The Elixhauser index measures thirty comorbid conditions and is known to predict hospital mortality.23 Using DRGs, the index distinguishes comorbidities from complications by considering only secondary diagnoses unrelated to the principal diagnosis. All Elixhauser comorbidities were be used in the multivariate models.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the factors that independently predicted lack of definitive therapy. The logistic regression analysis modeled the odds of not undergoing cholecystectomy. Stepwise backwards methods were used to generate a parsimonious model and the likelihood ratio test and AIC criteria were used to determine goodness-of-fit. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are reported.

Statistical Analysis: Readmissions

For patients discharged from the hospital alive, the subsequent gallstone-related trajectory of care in the two years after initial hospitalization is described. This includes readmission rates, subsequent cholecystectomy rates for patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy, and two-year mortality rates. Gallstone-related readmissions were identified by a primary ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis code listed in Table 1, plus 574.2, 574.20, and 574. 21 for “calculus of the gallbladder without evidence of cholecystitis” which represents intractable biliary colic requiring hospitalization, or gallstone pancreatitis identified by a primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code of 577.0 and a secondary diagnosis code starting with 574 or 575. Readmissions for surgical complications were identified by ICD-9-CM codes 998.0 to 998.9, 997.4, 997.5, and 997.

To calculate gallstone-related readmission rates in the two years following initial hospitalization (including complications from surgery and cholecystectomy after discharge), we used a Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis. The analysis measures the time to first readmission or subsequent cholecystectomy (whichever occurred first) to obtain cumulative gallstone-related readmission rates. Patients who died before readmission or subsequent cholecystectomy were treated as censored, as these patients were no longer “at risk” for gallstone-related readmissions. In patients who did not undergo definitive therapy, a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the factors that independently predicted gallstone-related acute care readmissions excluding subsequent cholecystectomy.

The median total charges and total Medicare reimbursement for readmissions is reported. This analysis is not a cost-benefit analysis, but meant to demonstrate the additional cost associated with gallstone-related readmissions.

Statistical Analysis: Survival

For patients surviving to discharge from initial hospitalization, the subsequent 2-year survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. 2-year survival rates were compared in the cholecystectomy and no cholecystectomy group using a log-rank test, with P<0.05 considered significant. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the independent effect of cholecystectomy on 2-year survival after controlling for patient demographics, Elixhauser comorbidities, and diagnosis.

RESULTS

Overall Cohort (Table 2)

Table 2.

Demographics and Elixhauser Comorbidities in Overall Cohort, Cholecystectomy, and No Cholecystectomy Groups

| Variables | Overall cohort, n=29,818 |

Cholecystectomy, n=22,367 |

No cholecystectomy, n=7,451 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y (mean) | 77.7±7.3 | 77.0±6.9 | 79.8±7.9 | <0.0001 |

| Female, % | 58 | 57 | 61 | <0.0001 |

| White, % | 89 | 89 | 87 | <0.0001 |

| African American, % | 6 | 6 | 7 | |

| Other race, % | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Admission type, % | ||||

| Emergency admission | 64 | 63 | 66 | <0.0001 |

| Urgent admission | 36 | 37 | 34 | |

| Weekend admission | 24 | 24 | 25 | 0.14 |

| Diagnosis, % | ||||

| Acute cholecystitis without CBD stones | 80 | 86 | 63 | <0.0001 |

| Acute cholecystitis with CBD stones | 20 | 14 | 37 | |

| Teaching status, % | ||||

| Major teaching hospital | 16 | 15 | 19 | <0.0001 |

| Minor teaching hospital | 22 | 23 | 20 | |

| Non-teaching hospital | 62 | 62 | 61 | |

| Other procedures, cholecystostomy tube, % | 0.5 | 0.05 | 1.7 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 15 | 12 | 22 | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease | 7 | 6 | 9 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11 | 10 | 15 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 52 | 52 | 54 | 0.0004 |

| Other neurological disorders than paralysis | 6 | 5 | 8 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 16 | 15 | 20 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 | 21 | 23 | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus w/ complications | 6 | 6 | 7 | 0.0011 |

| Hypothyroidism | 10 | 9 | 11 | <0.0001 |

| Renal failure | 3 | 2 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| Solid tumor w/out mets | 8 | 8 | 9 | 0.09 |

| Depression | 5 | 4 | 6 | <0.0001 |

Only comorbidities with >3 % prevalence in cohort shown.

CBD, common bile duct.

Between 1996 and 2005, inclusive, 29,818 Medicare beneficiaries were urgently or emergently admitted to acute care facilities for a first episode of acute cholecystitis with (N=5,944, 20%) or without (N=23,874, 80%) common bile duct stones. The mean age was 77.7 ± 7.3 years and 89% of patients were white. The percentages of patients with selected Elixhauser comorbidities are listed in Table 2.

Sixty-four percent of admissions were classified as emergent and 36% were classified as urgent. Weekend admission accounted for 24% of all non-elective admissions. Forty percent of patients were admitted to a general medical physician, 24% were admitted to a general surgeon, 8% were admitted to a gastroenterologist, and 29% were admitted to other specialists. Admissions to non-teaching hospitals accounted for 62% of initial hospitalizations and 24% of admission occurred on weekends. The mean length of stay for the entire cohort was 6.4 ± 5.9 days (median = 5 days). Six hundred sixty-one patients died during initial hospitalization for an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 2.2%.

Cholecystectomy Rate during initial Hospitalization

Of the 29,818 patients, 22,367 (75%) underwent cholecystectomy, performed either laparoscopically (71%) or open (29%). The mean time to cholecystectomy was 2.1 ± 2.4 days (median = 1 day). The in-hospital mortality rate was 2.7% in patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy and 2.1% in patients who did (P=0.001). Cholecystostomy tubes were placed in 0.5% of patients (N=140 with 129 in no cholecystectomy group). The total length of stay was longer for patients who had cholecystectomy when compared to those who did not (median 5 vs. 4 days, P<0.0001). The total median charges and Medicare reimbursements were $17,608 and $7,632 for patients undergoing cholecystectomy and $9,699 and $4,251 for patients not undergoing cholecystectomy.

By univariate analysis, patients who were older, female, black, admitted emergently, admitted to a general medicine physician, admitted to a major teaching hospital, had a diagnosis of common bile duct stones, and had nearly any of Elixhauser comorbidities were less likely to undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization (Table 2). There was no consistent trend over time in cholecystectomy rates.

Multivariate Analysis: Factors Predicting Cholecystectomy during initial Hospitalization

To determine the factors predicting cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis, we performed a multivariate logistic regression modeling the odds of undergoing cholecystectomy (Table 3). Patients who were older, non-white, female, admitted emergently, admitted to a general medicine physician, evaluated by a gastroenterologist, or had common bile duct stones were less likely to undergo cholecystectomy.

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Modeling the Odds of Cholecystectomy During Initial Hospitalization

| Factor (reference group) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Age (5-yr increments) | 0.83 | 0.81 – 0.84 |

| African American race (white) | 0.68 | 0.60 – 0.76 |

| Female (male) | 0.94 | 0.88 – 0.99 |

| CBD stones (no stones) | 0.32 | 0.30 – 0.34 |

| Emergency admission (urgent) | 0.91 | 0.86 – 0.97 |

| <200 beds (>500 beds) | 0.85 | 0.77 – 0.94 |

| 200–350 beds (>500 beds) | 1.10 | 1.00 – 1.21 |

| 351–500 beds (>500 beds) | 1.12 | 1.01 – 1.24 |

| Medical service area <100,000 (>1,000,000) | 0.85 | 0.77 – 0.94 |

| Major teaching hospital (non) | 0.77 | 0.70 – 0.84 |

| Non-profit hospital (government) | 1.24 | 1.34 – 1.35 |

| Profit (government) | 1.21 | 1.07 – 1.35 |

| Admitting physician – medicine (surgeon) | 0.52 | 0.48 – 0.56 |

| Gastroenterology evaluation (no) | 0.57 | 0.51 – 0.65 |

| Congestive heart failure (no) | 0.64 | 0.59 – 0.70 |

| Valvular disease (no) | 0.83 | 0.74 – 0.93 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (no) | 0.79 | 0.72 – 0.86 |

| Other neurologic disease (no) | 0.84 | 0.75 – 0.94 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (no) | 0.80 | 0.74 – 0.86 |

| Liver disease (no) | 0.44 | 0.33 – 0.58 |

| Metastatic Cancer (no) | 0.57 | 0.44 – 0.74 |

| Coagulopathy (no) | 0.77 | 0.66 – 0.90 |

| Electrolyte abnormality (no) | 0.80 | 0.73 – 0.87 |

Individual Federal Information Processing Standards areas also significant, but not shown listed individually.

In addition, patients with the following comorbidities were less likely to undergo cholecystectomy: congestive heart failure, valvular disease, peripheral vascular disease, neurologic disorders other than paralysis, chronic lung disease, liver disease, metastatic cancer, coagulopathy, and fluid/electrolyte disorders. There was also variation in receipt of cholecystectomy by region and hospital characteristics including FIPS area, hospital size, medical service area, type of hospital (non-profit, profit, government), and teaching status.

Subsequent Gallstone-Related Healthcare Trajectory

The subsequent gallstone-related healthcare trajectories of patients who received definitive therapy during initial hospitalization and those that did not are summarized in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Of the 22,367 patients undergoing cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis, 21,907 were discharged from the hospital. 20,992 had no further readmissions related to gallstones. 915 patients required 1,474 readmissions for surgical complications and/or gallstone-related problems, most often retained common duct stones. Of the 915 readmitted patients, 556 were for operative complications and 359 were for gallstone-related problems (Figure 1). The 1,474 gallstone- or surgery-related readmissions had a median length of stay of 5 days per readmission. The mean total charges were $11,747 and the mean Medicare payment amount was $5,316.

Figure 1.

Subsequent gallstone-related trajectory of care in Medicare beneficiaries undergoing cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis.

Figure 2.

Subsequent gallstone-related trajectory of care in Medicare beneficiaries not undergoing cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis.

Of the 7,451 patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization, 7,250 survived to discharge. Their subsequent healthcare trajectory is shown in Figure 2. There were 4,576 patients that did not require readmission and did not undergo cholecystectomy. 1,064 patients in this group had no further gallstone-related admissions but died in the two-years following initial hospitalization and 2,972 remained alive had no further problems.

694 patients underwent outpatient cholecystectomy after discharge, without ever requiring readmission to an acute care facility. 1,980 patients required a total of 2,424 readmissions for gallstone- or surgery-related problems. The 2,424 gallstone-related readmissions had a median length of stay of 4 days per readmission. The median total charges were $13,687 and the mean Medicare payment amount was $7,115. In the 1,980 patients readmitted, 1,372 had a subsequent cholecystectomy and 608 did not. 37% of cholecystectomies performed on readmission for gallstone-related complications were done open, compared to only 29% during initial hospitalization (P<0.0001).

Kaplan-Meier Gallstone-Related Readmission Rates

The Kaplan-Meier gallstone-related readmission rates were calculated for both the cholecystectomy and not cholecystectomy group. Patients were treated as censored at the time of death. Gallstone- or surgery-related readmission rates were low in patients who underwent cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization, with 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 2-year readmission rates of 2.4%, 2.9%, 3.7%, and 4.4%. In patients who did not receive definitive treatment during initial hospitalization, the gallstone- or surgery-related readmission rates were significantly higher, with 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 2-year readmission rates of 21%, 29%, 35%, and 38% (Figure 3, P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier time to readmission in patients who do and do not undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis. The 30-day, 90-day, 1-year, and 2-year readmission rates were 2.4%, 2.9%, 3.7%, and 4.4% in patients undergoing cholecystectomy on initial hospitalization and 21%, 29%, 35%, and 38% in patients who did not (p<0.0001).

Factors Predicting Readmission in Patients without Cholecystectomy

In the multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, patients were again censored at the time of death or cholecystectomy. In the final model, age predicted gallstone-related readmissions. For each 5-year increase in age, patients were 8% more likely to require readmission (HR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.89 – 0.94) or, in other words, younger patients were at higher risk for readmission. In addition, male patients were 28% more likely to require readmission than female patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization (HR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.17 – 1.40). Patients who had common bile stones were 31% less likely to have gallstone-related readmissions (HR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.62 – 0.75) than patients with acute cholecystitis. The only Elixhauser comorbidities that influenced gallstone-related readmissions were valvular disease (HR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.60 – 0.83) and neurologic disorders (HR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.57 – 0.81), both of which decreased the likelihood of gallstone-related readmission.

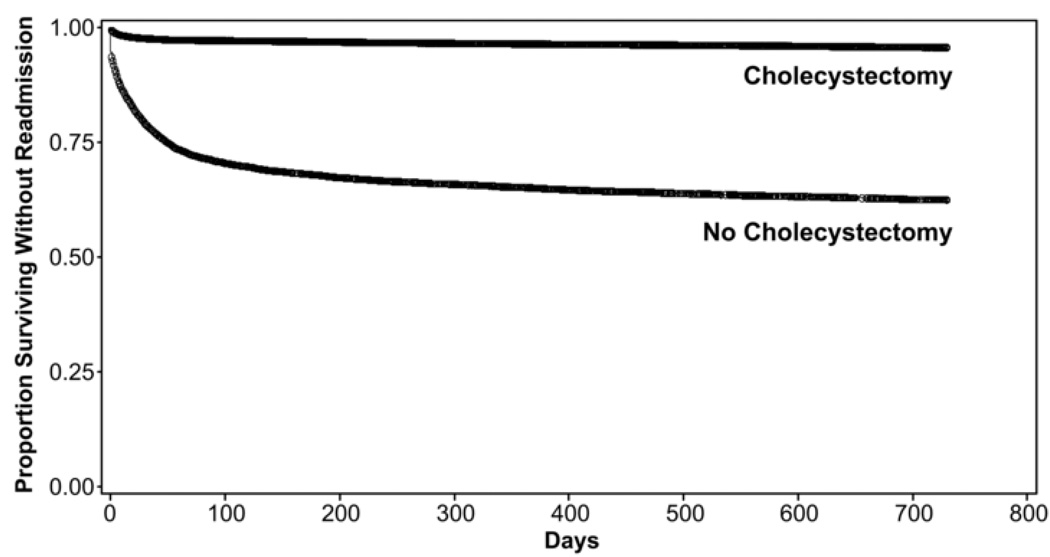

Kaplan-Meier Survival

As expected, the 2-year survival from the time of hospital discharge was lower in the group that did not undergo cholecystectomy (Figure 4). The 30-day, 1-year, and 2-year cumulative death rates were 2.0%, 9.5%, and 15.2% in the cholecystectomy group and 5.0%, 19.4%, and 29.3% in the no cholecystectomy group (P<0.0001) presumably because the sickest patients were not operated on. However, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy were 56% more likely to die than those who did (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.47 – 1.65), even after controlling for patient demographics and comorbidities (Table 4). Age, gender, and multiple comorbidities also predicted 2-year mortality.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier unadjusted 2-year survival in patients who do and do not undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis. The 30-day, 1-year, and 2-year cumulative death rates were 2.0%, 9.0%, and 15.2% in the cholecystectomy group and 5.0%, 19.4%, and 29.3% in the no cholecystectomy group (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model: Factors Predicting 2-year mortality

| Factor (reference group) | Hazard Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization (no cholecystectomy) | 1.56 | 1.47 – 1.65 |

| Age (5 year increments) | 1.39 | 1.36 – 1.41 |

| Male (female) | 1.19 | 1.23 – 1.26 |

| CBD stones (no stones) | 0.85 | 0.80 – 0.91 |

| Congestive heart failure (no) | 1.79 | 1.67 – 1.91 |

| Valvular disease (no) | 1.15 | 1.05 – 1.25 |

| Paralysis (no) | 1.17 | 1.00 – 1.37 |

| Other neurologic disease (no) | 1.51 | 1.38 – 1.65 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (no) | 1.23 | 1.15 – 1.33 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (no) | 1.41 | 1.32 – 1.51 |

| Depression (no) | 1.18 | 1.06 – 1.31 |

| Hypertension (no) | 0.91 | 0.86 – 0.96 |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | 1.29 | 1.20 – 1.39 |

| Deficiency anemia | 1.22 | 1.14 – 1.31 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.16 | 1.03 – 1.31 |

| Weight loss | 1.24 | 1.07 – 1.43 |

| Diabetes mellitus (no) | 1.34 | 1.26 – 1.43 |

| Metastatic Cancer (no) | 2.90 | 2.46 – 3.40 |

| Renal Failure (no) | 1.74 | 1.55 – 1.96 |

| Liver disease (no) | 1.91 | 1.55 – 2.36 |

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that 25% of Medicare beneficiaries admitted with acute cholecystitis do not undergo cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization. Lack of definitive therapy is associated with a 38% gallstone-related readmission rate over the subsequent two years, compared to only 4% in patients who undergo cholecystectomy. Twenty-seven percent of patients who do not undergo definitive therapy require subsequent cholecystectomy, often not performed electively, but associated with acute care readmission. Gallstone-related readmissions are expensive for Medicare, leading to approximately $14,000 in total charges and greater than $7,000 in Medicare payments per readmission. Cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization is associated with improved 2-year survival even after controlling for patient comorbidities.

In addition, while early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis has been studied and shown to be safe,8–18, 21 to our knowledge ours is the first U.S-based population-based study evaluating the rate for acute cholecystitis in elderly patients. Our study demonstrates that the use of cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis is appropriate and safe, with low rates of further gallstone-related problems and low gallstone-related readmission rates. The conversion/open cholecystectomy rate of 71% for elderly patients with acute cholecystitis in our study is similar to the reported conversion/open in previous single-institution studies.24–27 The 2.1% in-hospital mortality rate for acute cholecystitis is consistent with the 0.5–2.5% rate reported for elective cholecystectomy in elderly patients25, 28, 29 and actually much lower than a 1980s reports of 10–19% mortality for emergency cholecystectomy in elderly patients.25, 26

It is encouraging that we found adherence to the published guidelines in 75% of Medicare beneficiaries. However, the 38% gallstone-related readmission rate and 27% subsequent cholecystectomy rate offer a significant opportunity for improvement. As with any observational study, it is clear from our analysis that there is significant selection bias for performance of cholecystectomy. Patients with more comorbidities were less likely to undergo cholecystectomy. Comorbidities clearly predict 2-year mortality, but lack of definitive therapy also independently predicts mortality suggesting that failure to perform cholecystectomy increases mortality above and beyond the expected mortality associated with the patients’ preexisting disease. The presence of these disease processes alone should not be a contraindication to cholecystectomy when the clinical situation is appropriate. While it is unrealistic to expect a 100% cholecystectomy rate during initial hospitalization, the regional differences imply that factors independent of comorbid illness are at play and cholecystectomy is likely not performed often enough in some settings. The lower than 2% rate of cholecystostomy tube placement in the no cholecystectomy group suggests that these patients weren’t severely ill and requiring stabilization, but rather other factors influenced receipt of cholecystectomy. This study prompted us to review of our own hospital data. We noted that patients who do not receive definitive therapy rarely do so because they are simply too sick to tolerate it, but rather, it is an issue of operating room time, surgeon time, and multiple other factors. Locally, we have used these data to implement a pathway to maximize cholecystectomy rates during initial emergency admission for gallstone-related complications. This will be the subject of a future report.

Our study enables us to identify both patients at high-risk for not receiving definitive therapy and those at high-risk for readmission if they do not. Interventions to improve cholecystectomy rates should target risk factors identified in this study including improving the rate of admission to or consultation by a surgeon and eliminating racial and regional disparities.

We recognize that this study has several limitations. We used the Medicare “type of admission” variable to differentiate urgent/emergent admissions from elective admissions. We further increased the sensitivity by eliminating ICD-9-CM codes for gallstones without cholecystitis, even though intractable biliary colic might be considered an urgent or emergent admission. It is possible that some of these admissions were misclassified and some patients undergoing elective cholecystectomy were included in the cohort. If so, this would falsely elevate our cholecystectomy rate, as elective admissions for the purpose of cholecystectomy would all undergo definitive therapy. Another weakness is our inability to determine time from onset of symptoms to presentation using administrative data. It is possible that some patients who did not receive cholecystectomy had symptoms for greater than 48–72 hours, for which many delayed cholecystectomy.11, 13, 30, 31 However, it is often difficult to determine exact onset of symptoms and others have demonstrated that cholecystectomy during index admission is safe within seven days of onset of symptoms.21, 32

In summary, elderly patients are more likely to present with complicated gallstone disease than younger patients. The delayed presentation and associated comorbidities present unique challenges in the management of such patients. Our data demonstrate that cholecystectomy during initial hospitalization is appropriate in elderly patients with urgent/emergent admission for acute cholecystitis and failure to perform cholecystectomy increases readmission rates, 2-year mortality, and cost in elderly patients. In 25% of Medicare beneficiaries, cholecystectomy was not performed during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis, leading to 38% cumulative readmission rate in the two years after discharge. For patients requiring readmission and subsequent cholecystectomy, the number of open procedures was increased and the total Medicare payments were $7,000 for each additional admission. Cholecystectomy should be performed during initial hospitalization for acute cholecystitis to prevent recurrent episodes of cholecystitis, multiple readmissions, and increased costs. These data can be used to develop guidelines and implement quality measures that maximize definitive therapy in older patients at high-risk for recurrent gallstone-related problems, thereby preventing unnecessary episodes of care. In the future, we can expand our research to understand current rate and role of elective cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones before they present with complicated disease. This will be critical in this challenging population, as their high comorbidity rates often dissuade elective surgery. Further studies will allow us to further assess the appropriateness and timing of gallbladder surgery in the elderly, thereby improving healthcare decision making for the most common abdominal surgical disease occurring in this age group.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Presented at Southern Surgical Association 121st Annual Meeting, Hot Springs, VA, December 2009.

Contributor Information

Taylor S Riall, Department of Surgery, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Dong Zhang, Internal Medicine, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Courtney M Townsend, Jr, Department of Surgery, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

Yong-Fang Kuo, Internal Medicine, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

James S Goodwin, Internal Medicine, The University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, et al. Surgical rates and operative mortality for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:403–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consensus Statement. 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang WK, Lee FM, Santen S. [Accessed 07/28/09];Cholelithiasis [EMedicine web site] 2008 Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/774352-overview. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gracie WA, Ransohoff DF. The natural history of silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:798–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209233071305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McSherry CK, Ferstenberg H, Calhoun WF, et al. The natural history of diagnosed gallstone disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ann Surg. 1985;202:59–63. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198507000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khang KU, Wargo JA. Gallstone disease in the elderly. In: Rosenthal RA, Zenilman ME, Katlic MR, editors. Principles and Practice of Geriatric Surgery. Verlag: Springer; 2001. pp. 690–710. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krasman ML, Gracie WA, Strasius SR. Biliary tract disease in the aged. Clin Geriatr Med. 1991;7:347–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandler CF, Lane JS, Ferguson P, et al. Prospective evaluation of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of acute cholecystitis. Am Surg. 2000;66:896–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvinen HJ, Hastbacka J. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective randomized study. Ann Surg. 1980;191:501–505. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198004000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson M, Thune A, Blomqvist A, et al. Management of acute cholecystitis in the laparoscopic era: results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:642–645. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(03)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahtinen J, Alhava EM, Aukee S. Acute cholecystitis treated by early and delayed surgery. A controlled clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1978;13:673–678. doi: 10.3109/00365527809181780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai PB, Kwong KH, Leung KL, et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:764–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:461–467. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McArthur P, Cuschieri A, Shields R, et al. Controlled clinical trial comparing early with interval cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:676–678. doi: 10.1177/003591577506801103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norrby S, Herlin P, Holmin T, et al. Early or delayed cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis? A clinical trial. Br J Surg. 1983;70:163–165. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shikata S, Noguchi Y, Fukui T. Early versus delayed cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Today. 2005;35:553–560. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-2998-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui T, MacDonald A, Chong PS, et al. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Surg. 2008;195:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter JG. Acute cholecystitis revisited: get it while it's hot. Ann Surg. 1998;227:468–469. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheruvu CV, Eyre-Brook IA. Consequences of prolonged wait before gallbladder surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:20–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegel JH, Kasmin FE. Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut. 1997;41:433–435. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurusamy KS, Samraj K. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Cochran Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005440.pub2. Article number: CD005440.(4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen GC, Tuskey A, Jagannath SB. Racial disparities in cholecystectomy rates during hospitalizations for acute gallstone pancreatitis: a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2301–2307. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnuson TH, Ratner LE, Zenilman ME, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: applicability in the geriatric population. Am Surg. 1997;63:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houghton PW, Jenkinson LR, Donaldson LA. Cholecystectomy in the elderly: a prospective study. Br J Surg. 1985;72:220–222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margiotta SJ, Jr, Horwitz JR, Willis IH, et al. Cholecystectomy in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1988;156:509–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman MG, Russell JC, Lynch JT, et al. Comparison of mortality rates for open and closed cholecystectomy in the elderly: Connecticut statewide survey. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1994;4:165–172. doi: 10.1089/lps.1994.4.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girard RM, Morin M. Open cholecystectomy: its morbidity and mortality as a reference standard. Can J Surg. 1993;36:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pessaux P, Tuech JJ, Derouet N, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly: a prospective study. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1067–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolla SB, Aggarwal S, Kumar A, et al. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1323–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koo KP, Thirlby RC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. What is the optimal timing for operation? Arch Surg. 1996;131:540–544. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430170086016. discussion 544–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tzovaras G, Zacharoulis D, Liakou P, et al. Timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective non randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5528–5531. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]