Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the intracellular pathogen that infects macrophages primarily, is the causative agent of the infectious disease tuberculosis in humans. The Mtb genome encodes at least six epoxide hydrolases (EHs A to F). EHs convert epoxides to trans-dihydrodiols and have roles in drug metabolism as well as in the processing of signaling molecules. Herein, we report the crystal structures of unbound Mtb EHB and Mtb EHB bound to a potent, low-nanomolar (IC50 ≈19 nM) urea-based inhibitor at 2.1 and 2.4 Å resolution, respectively. The enzyme is a homodimer; each monomer adopts the classical α/β hydrolase fold that composes the catalytic domain; there is a cap domain that regulates access to the active site. The catalytic triad, comprising Asp104, His333 and Asp302, protrudes from the catalytic domain into the substrate binding cavity between the two domains. The urea portion of the inhibitor is bound in the catalytic cavity, mimicking, in part, the substrate binding; the two urea nitrogen atoms donate hydrogen bonds to the nucleophilic carboxylate of Asp104, and the carbonyl oxygen of the urea moiety receives hydrogen bonds from the phenolic oxygen atoms of Tyr164 and Tyr272. The phenolic oxygen groups of these two residues provide electrophilic assistance during the epoxide hydrolytic cleavage. Upon inhibitor binding, the binding-site residues undergo subtle structural rearrangement. In particular, the side chain of Ile137 exhibits a rotation of around 120° about its Cα–Cβ bond in order to accommodate the inhibitor. These findings have not only shed light on the enzyme mechanism but also have opened a path for the development of potent inhibitors with good pharmacokinetic profiles against all Mtb EHs of the α/β type.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, epoxide hydrolase, hydrolase fold, enzyme mechanism, inhibitor design

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infects one-third of the world’s population; approximately 2 million people die every year because of tuberculosis (TB) despite the worldwide use of the bacille Calmette–Guerin vaccine and several antibiotics.1 Someone gets newly infected by Mtb every 4 seconds and someone dies of TB every 15 seconds.1 TB has remained the ‘Captain of Death’ in Asia and Africa. Therefore, the development of new anti-TB compounds is of paramount importance. Furthermore, the emergence of multidrug resistant and extensively drug resistant strains of this debilitating human pathogen has led to further studies designed to explore the various factors responsible for the survival of this organism. The Mtb structural genomics consortium†, formed in 2000, aims to determine the three-dimensional structures of Mtb proteins that not only would advance the understanding of Mtb pathogenesis but also will help in the development of small-molecule inhibitors against potential drug targets using a structure-based drug design approach.2 In fact, several promising small-molecule anti-TB compounds have emerged through this approach.3

Sequencing of the complete genome of Mtb strain H37Rv (4.4 Mbp) has revealed the genes for at least six potential epoxide hydrolase (EH) proteins (open reading frames Rv0134, Rv1124, Rv1938, Rv2214c, Rv3617, and Rv3670) belonging to the virulence, detoxification, and adaptation functional category that encompasses 2.4% of the entire Mtb genome.4 EHs convert epoxides to trans-dihydrodiols, and in numerous organisms, EHs have demonstrated roles in detoxification as well as in the regulation of signaling molecules that affect homeostasis and defense systems.5 In mammals, EHs, present in large quantities in the liver, are drug targets for the regulation of blood pressure, inflammation, cancer progression, and kidney failure6–8; numerous orally and metabolically stable inhibitors have been developed against these mammalian EHs.9,10

The structure of Rv2470 from Mtb, initially annotated as a conserved hypothetical protein, revealed an atypical EH, not of the α/β fold type, and similar to that of limonene-1,2 EH from Rhodococcus erythropolis.11,12 Sequence analyses show that the Mtb genome encodes around 30 EHs including the 6, listed above, that are annotated as EHs. The presence of such a large number of EHs in Mtb suggests that they might be essential for the survival of this bacterium. El-Etr et al. have identified two loci in the Mycobacterium marinum (Mtm) genome, mel1 (genes melA, melB, melC, melD, and melE) and mel2 (genes melF, melG, melH, melI, melJ, and melK), of which mel2 is unique to Mtm and Mtb.13 It has been shown that Mtm mutants with mutations in mel1 and mel2 lose their ability to infect both murine and fish macrophage cell lines.13 The Mtb homologue of the locus mel2 consists of genes: Rv1936, Rv1937, Rv1938, Rv1939, Rv1940, and Rv1941. Among these, Rv1938 shares 82% sequence identity with the corresponding Mtm gene, melH, of the mel2 locus. In light of these findings, we reasoned that Rv1938 (EHB) could be a potential drug target, although TraSH analysis suggests that EH genes are not required for the growth or survival of Mtb during infection.14,15 The three-dimensional structures of Mtb EHB should help to shed light on their biological functions and should also help in developing small-molecule inhibitors against these enzymes. Such inhibitors could elucidate the biological role of the enzymes. In this article, we report the crystal structures of Mtb EHB and its complex with a urea-based inhibitor whose IC50 value is 19 nM. The details of the three-dimensional structure, the enzyme mechanism, and the mode of inhibitor binding are discussed here.

Results and Discussion

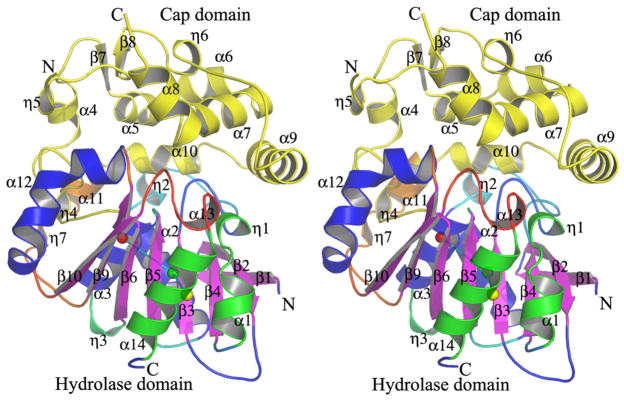

The molecular structure

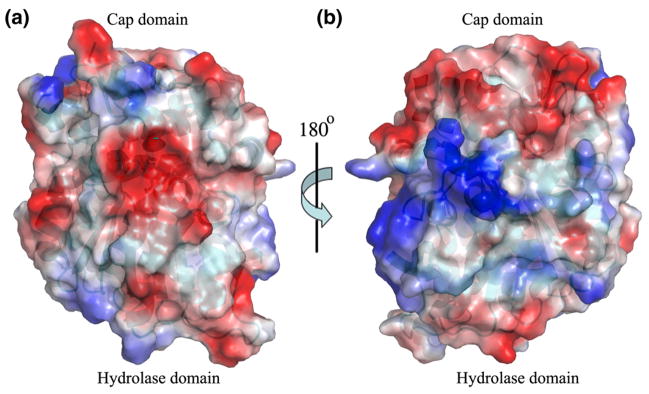

The structures of soluble EHs (sEHs) from humans (555 aa) and mice (554 aa), which were determined previously, have two separate and distinct domains, an N-terminal domain (residues 1–223) that has a fold resembling that of a haloacid dehalogenase and a C-terminal domain (residues 228–555) that corresponds to the EH catalytic domain.16,17 The polypeptide chain of EHB (356 aa) from Mtb folds as a single globular protein consisting of two domains, a catalytic α/β hydrolase domain and a cap domain. The structure of EHB is similar to that of the C-terminal domains of the human and mouse sEHs.16,17 The hydrolase domain is composed of an eight-stranded, mostly parallel, curved β-sheet sandwiched between five α-helices, a hallmark of the α/β hydrolase fold (Fig. 1). Helices α1 and α14 are packed on one side of the β-sheet, whereas helices α2, α3, and α12 are packed on the other side of the central β-sheet. If one calculates the centroid of the atomic coordinates of helices α1 and α14 and of helices α2, α3, and α12, these two centroids are located approximately equidistant (10.5 Å) from the centroid of the atomic coordinates of the strands of the central β-sheet (Fig. 1). Domain 2, the cap, consists of seven α-helices and intervening flexible loops (Fig. 1). The hydrolase domain is composed of residues 1–129 and 276–356 (59% of the total number of amino acids); the cap domain consists of residues 130–275 (41% of the total number of amino acids). The hydrolase domain is relatively more rigid than the cap domain; this is evident from the low average B-factor (46.2 Å2) of the atoms that belong to the hydrolase domain relative to the average B-factor of the atoms of the residues comprising the cap domain (61.8 Å2). The first three N-terminal residues of the polypeptide chain and seven residues of the cap domain (207 to 213) are missing in the structure because they are disordered and the electron density associated with these residues is poorly defined. Computation of the electrostatic surface potential suggests that overall the molecule is negatively charged (−12.00 e) (Fig. 2); the cap domain is relatively more negatively charged than the hydrolase domain. The active-site pocket is negatively charged. Human and murine sEHs also exhibit a similar surface charge distribution.

Fig. 1.

Stereo view of the Mtb EHB secondary structural features. The β-strands of the hydrolytic domain are labeled β1–β6 and β9 and β10 and represented by arrows. Those β-strands of the cap domain are labeled β7 and β8. The a and 310 helices are labeled α1–α14 and η1 to η7 respectively. The β-sheet sits midway between helices α1 and α14 and helices α2, α3, and α12. The average distance separating these secondary structural features is 10.5 Å. The center of coordinates of helices α1 and α14, of helices α2, α3, and α12, and of the β-sheet are shown in yellow, red, and green spheres, respectively. The cap domain is shown in yellow.

Fig. 2.

(a) A surface charge distribution representation of Mtb EHB. The red regions of the surface correspond to negative charges; the blue corresponds to positively charged region and the white regions correspond to neutral charges, respectively. (b) Rotation of the Mtb EHB around a vertical axis by 180° as indicated.

The asymmetric unit of the crystal contains a monomeric EHB of molecular mass 39,265 Da; however, the crystallographic 2-fold symmetry operator of space group P41212 generates a dimer, an observation that is supported by the size-exclusion gel chromatography results (data not shown). The Matthews coefficient and solvent content are 2.2 Å3/Da and 42.8%, respectively. The catalytic units of EHs from other organisms are also dimers.16–19 The dimer interface is stabilized by van der Waals and hydrogen-bonding interactions; 2330 Å2 of surface area is buried at the interface as compared to the total accessible surface area of each monomer, 13,570 Å2. There are a total of 325 hydrogen-bonding interactions in each monomer and nine unique H bonds in the dimer interface. Strands β1 and β2, the loop connecting strand β4 and helix α2, and helices α6, α7, α9, and α10 of one monomer are packed against the corresponding regions of the other monomer in a diagonal manner (Supplementary Fig. 1). Human and mouse EHs have similar monomer–monomer packing in the dimer interface.

Structural comparisons to other EH enzymes

A structural comparison of Mtb EHB with its human, murine, Agrobacterium radiobacter, and Aspergillus niger counterparts and with other hydrolytic enzyme such as the haloalkane dehaloge-nases16–20 suggests that the hydrolase domains overlap well, but that the cap domains exhibit many subtle structural rearrangements. In particular, superimposition of Mtb EHB onto the C-terminal domain (residues 245–542) of the murine EH, the molecule that was chosen as the search model for the structure determination, shows a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) value of 1.4 Å (273 Cα pairs). A substantial part of this difference is due to the poor agreement in the residues of the cap domain. On the other hand, the hydrolase domains agree relatively better (rmsd, 0.93 Å, 185 Cα pairs). Furthermore, the superimposition of human and murine EH structures results in an rmsd value of 0.51 Å (287 Cα pairs). This shows that the mammalian enzymes are very similar to one another but differ substantially from the bacterial EHs (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

(a) A stereo view of superimpositions of the Cα atoms between the structures of Mtb EHB (magenta) and human sEH (green) (rmsd value 1.3 Å) and between the structures of Mtb EHB and murine sEH (blue) (rmsd value 1.4 Å) showing the similarity and differences among the structures. The major structural difference is in the loop connecting the hydrolase domain to the cap domain. The catalytic residues are shown in stick representation. (b) A close-up view of the human EH (green) and Mtb EHB (magenta) substrate binding pockets. Residues that border the binding pocket are shown by stick representation. The residue numbering corresponds to that of Mtb EHB. Color codes are the same as that in (a).

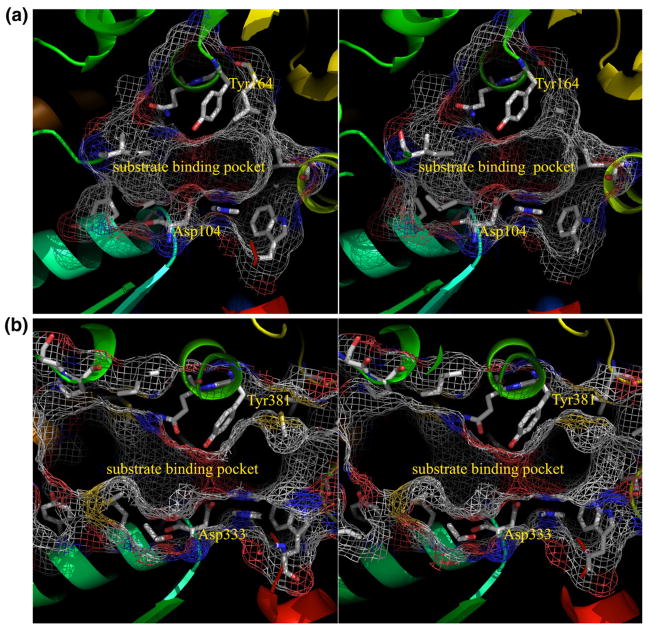

From the structure-based drug design prospective it is imperative to compare the structure of Mtb EHB with its human counterpart in more detail. The least-squares superimposition between the two structures results in an rmsd value of 1.3 Å (276 Cα pairs). Furthermore, the disposition of the catalytic residues is essentially the same in the two structures. However, in Mtb EHB, the conformation of residues 132–149 (part of the long loop comprising residues 127 to 149 that connect the hydrolase domain to the cap domain), 190–206 and 214–226 of the cap domain, and 303–315 of the hydrolase domain are significantly different from the corresponding chain segments in human sEH (Fig. 3b). In Mtb EHB, these regions result in a closed substrate binding cavity, whereas in the human sEH structure, the substrate binding region is open to bulk solvent (Fig. 3b). Moreover, these chain segments are longer in Mtb EHB than the corresponding regions in the human sEH. The volume of the cavity adjacent to the active site of Mtb EHB is approximately 450 Å3 (Fig. 4a). This is a relatively small volume compared to the equivalent volume computed for the sEH of humans, 1650 Å3 (Fig. 4b). The residues that border the substrate binding pocket are listed in Table 1. Notably, in both human EH and Mtb EHB, the pocket is composed predominantly of hydrophobic residues except the catalytic residues. Clearly the structures suggest that the substrate specificity for the Mtb EHB is for a much smaller molecule than that for human sEH. Should Mtb EHB be a potential target, this difference in substrate specificity would be an advantage in antibiotics design.

Fig. 4.

Stereo view of the active-site pockets, shown by mesh representation, of the Mtb EHB (a) and of human sEH (b). The residues that border the active-site pocket are shown by stick representation with carbon atoms in gray.

Table 1.

Residues that border the substrate binding pocket

| Mtb EHB | Human EH |

|---|---|

| Phe36, Asp104, Trp105, Pro108, Val129, Pro130, Ile137, Gly138, Leu139, Trp163, Tyr164, Gln165, Phe168, Leu189, Val193, Leu226, Tyr272, Val303, Gly304, Trp307, Gly308, His333, Trp334 |

Phe265, Pro266, Met308, Asp333, Trp334, Met337, Tyr341, Thr358, Pro359, Phe360, Ile361, Pro362, Ala363, Asn364, Met367, Ser368, Pro369, Ser372, Ile373, Val378, Phe379, Tyr381, Gln382, Phe385, Leu395, Ser405, Leu406, Arg408, Ala409, Ser410, Ser413, Val415, Leu416, Met418, Leu427, Tyr465, Met468, Asn471, Trp472, Trp474, Ala475, Lys494, Asp495, Phe496, Val497, Leu498, Met502, Gly522, His523, Trp524 |

The kinetic study that is described below shows that Mtb EHB indeed has a very different substrate specificity than its mammalian counterparts. The other regions of the Mtb EHB structure that have conformations significantly different from those of the human sEH are the N-terminus of the hydrolase domain (residues 20–29), residues 150–163, and residues 227–250 of the cap domain (Fig. 3a). These regions are also longer in the Mtb EHB structure than those corresponding segments in the human EH.

There is another EH known as limonene EH (LEH). LEH converts limonene-1,2 epoxide to limonene-1,2 diol. The crystal structure of LEH from R. erythropolis has been determined.12 The structure consists of a six-stranded mixed and highly twisted β-sheet with three α-helices packed on one side of it. The structure of Mtb EHB is very different from that of LEH and the two structures cannot be superimposed. The catalytic triad of LEH is composed of Asp-Arg-Asp, whereas the catalytic triad of the sEHs and the EHB from Mtb consists of Asp-His-Asp; the disposition of the residues that form the catalytic triad is significantly different in both classes of EHs.

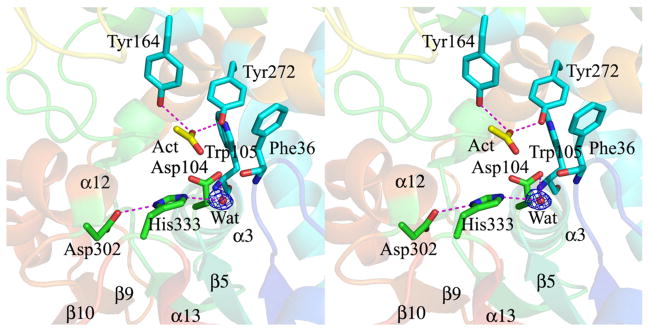

The active site

The residues forming the active site (Fig. 5) and the substrate binding site of Mtb EHB are on the periphery of the cavity (~450 Å3) that lies between the hydrolase domain and the cap domain. As with the other enzymes of the α/β hydrolase family, Mtb EHB has a catalytic triad comprising the nucleophilic Asp104, a general base His333, and hydrogen-bonded to His333, a second Asp302. The nucleophile is the ionized carboxylate of Asp104 and this residue is on a short loop connecting strand β5 to helix α3, known as the “nucleophilic elbow”.

Fig. 5.

Stereo view of the residues contributing to the active site of Mtb EHB. The nucleophile Asp104, general base His333, and the orienting acid Asp302 that form the catalytic triad are shown in stick model with carbon atoms in green. Try164 and Tyr272 that act as the general acid catalysts during the hydrolysis reaction are shown in stick model with carbon atoms in cyan. Phe36 and Trp105 that stabilize the tetrahedral intermediate are also shown in stick model with carbon atoms in cyan. The catalytic water (red sphere) and an acetate molecule (in stick model with carbon atoms in yellow) in the active site are shown. Hydrogen-bonding interactions are shown by magenta dotted lines. Also shown is the |Fo| − |Fc| electron density map (blue) at the 3σ level for the active-site water molecule.

His333 is not a general base for Asp104; rather, it is a general base to activate a water molecule for the second step of the reaction. His333 resides on a longish loop that connects strand β10 and to the small penultimate C-terminal helix α13 of the hydrolase domain (Fig. 5). Asp302 plays an orienting role for the imidazole group of His333. Atom Oδ1 of Asp302 makes a hydrogen bond with atom Nδ1 of the imidazole ring of His333. Asp302 is on the loop that connects strand β9 and helix α12 of the hydrolase domain (Fig. 5).

Several other residues lining the active-site cavity play important roles in the mechanism. Tyr164 and Tyr272 contribute to the formation of an oxyanion binding site for the epoxide oxygen atom of a substrate. The water molecule that is hydrogen-bonded to Nε2 of the general base His333 likely acts as the nucleophile in the second step of the reaction. The main-chain NH groups of Phe36 and Tyr105 both contribute to forming a second oxyanion hole that helps to stabilize the oxygen of Asp104 in the tetrahedral intermediate of the second step of the reaction mechanism (Fig. 5). There is an acetate ion located in the active-site cavity of the unbound EHB; one of the oxygen atoms of the carboxylate group form H bonds with the phenolic OH groups of Tyr164 and Tyr272 (Fig. 5). The role of these above residues in the hydrolysis of epoxides is evident not only from the EHB/inhibitor complex structure, described later in this article, but also from the sequence alignment with EHs from other organisms.

Substrate kinetics and inhibitors of Mtb EHB

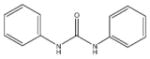

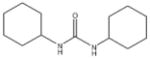

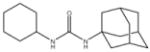

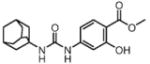

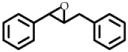

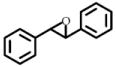

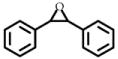

In order to establish that Rv1938 effectively encodes for an EH, we tested the ability of the purified recombinant EHB to hydrolyze several commonly used epoxide-containing substrates (Table 2). The enzyme displays a good specific activity for the three relatively small aromatic substrates tested (1–3). Like mammalian and plant sEHs,21 Mtb EHB is roughly 10-fold more active on [3H]trans-1,3-diphenylpropene oxide (1) than [3H] trans-stilbene oxide (2). However, the bacterial enzyme is twice more active on the [3H]cis-stilbene oxide (3) than on the trans-isomer 2, contrary to the described mammalian and plant sEHs.21 Whereas Mtb EHB is active against the terpenoid epoxide 4, no detectable activity was found for epoxy-stearic acid 5. These results indicate a substrate selectivity of Mtb EHB, and thus a biological role, very different from the one reported for the mammalian or plant sEH.5 We also tested the activity of Mtb EHB towards a fluorescent substrate 6 that was developed to screen inhibitors of the mammalian sEH.22 While the activity of Mtb EHB is relatively low for 6, it was high enough to allow us to screen the potency of 20 urea-based EH inhibitors (Table 3). Overall, there is no correlation (r2 = 0.06) between the inhibitor selectivity of Mtb EHB and of the human sEH, suggesting that it will be necessary to directly screen the bacterial enzyme to find the best inhibitor for it. Furthermore, there is little risk that such inhibitors will cross-react with the human sEH and lead to undesirable side effects.5 The bacterial enzyme is inhibited more effectively by small aromatic compounds such as 7, whose structure is similar to the best substrate 1 found. For 7, the IC50 (19 nM) is very close to the enzyme concentration used in the assay ([E]=30 nM), suggesting a tight binding competitive inhibition. Interestingly, the potency of 7 was reduced by an order of magnitude in the presence of substituents on the phenyl rings (8–11) or by replacing both aromatic rings with two cycloalkyl rings (12 and 13); however, an inhibition potency similar to that of 7 is obtained when only one phenyl ring was replaced by adamantyl 14. The replacement of one of the urea substitution by more polar and larger groups (15–26) results in a large loss of inhibition potency. Overall, these results confirm the structural results that the active site of Mtb EHB is relatively small and hydrophobic.

Table 2.

Substrate selectivity of the purified recombinant Mtb EHB

| Substrate Structure | No. | [S] (μM) | Specific activity (nmol min−1 mg−1) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 | 50 | 1050 ± 10 | 100 |

|

2 | 50 | 140 ± 10 | 13 |

|

3 | 50 | 360 ± 20 | 34 |

| 4 | 50 | 220 ± 30 | 21 | |

| 5 | 50 | < 5 | < 1 | |

| 6 | 5 | 60 ± 10 | 6 |

Results are means ± standard deviations of three separate measurements.

Table 3.

Inhibition of the purified recombinant Mtb EHB by a series of urea-based inhibitors and comparison with the human soluble EH

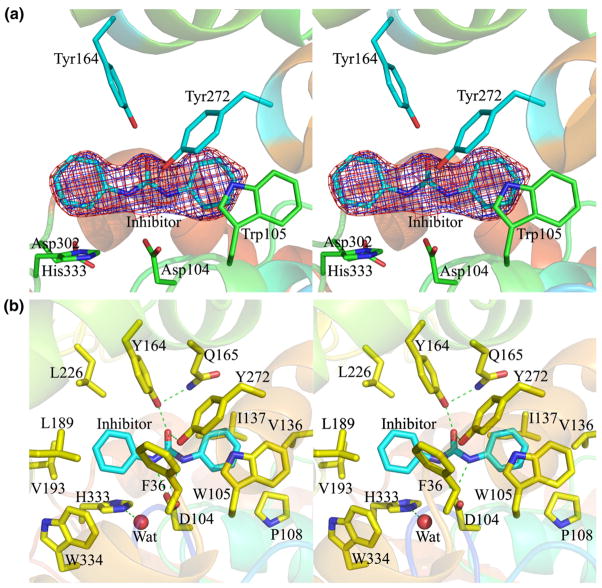

Potent inhibitor binding to Mtb EHB

The discovery of potent low-nanomolar urea-based inhibitors (Table 3) has encouraged us to obtain the structures of these inhibitors bound to EHB. Not only will the structure of the complex provide insights into the enzyme mechanism but also, it will aid in the understanding of the enzyme inhibition at the molecular level. Such knowledge will aid in improving on this inhibitor by increasing its potency and an enhanced pharmacokinetic profile if it shows promise as an antibiotic. We have been able to obtain the structure of EHB bound to the carbanilide inhibitor (C13H12O1N2, compound 7 in Table 3) at 2.4 Å resolution. This compound, comprising a central urea moiety with two benzyl groups linked to the two nitrogen atoms of the urea motif, is a flat and symmetrical molecule with a C2 symmetry axis passing through the carbonyl group of the urea motif. The mode of inhibitor binding to EHB was identified unambiguously from a difference Fourier |Fo| − |Fc|, αc electron density map. The inhibitor binds tightly to EHB; this is evident from the quality of the electron density map (Fig. 6a). The residues that border the inhibitor binding pocket are Phe36, Asp104, Trp105, Pro108, Val136, Ile137, Tyr164, Gln165, Leu189, Val193, Leu226, Tyr272, His333, and Trp334 (Fig. 6b). Among these, Phe36, Tyr164, Leu189, Val193, His333, and Trp334 are packed onto one side of the symmetry axis of the inhibitor, whereas Trp105, Pro108, Val136, Ile137, Gln165, and Tyr272 are packed on the other side of the symmetry axis. The side-chain atoms (Cβ, Cγ, Oδ1, and Oδ2) of Asp104, the carbonyl group of the inhibitor, and the phenolic Oη atoms of Tyr164 and Tyr272 are almost coplanar. The binding pocket is relatively hydrophobic and encloses a volume of ~450 Å3, around 15 times the volume of a water molecule (30 Å3). The Oδ1 atom of Asp104 is hydrogen bonded (both 2.9 Å) to the amide nitrogen atoms of the urea moiety of the inhibitor (Fig. 6b). The carbonyl oxygen atom of the urea motif of the inhibitor makes two hydrogen bonds, one to Tyr164 (2.5 Å) and one to Tyr272 (3.2 Å). Other interactions between the enzyme and the inhibitor are mainly van der Waals contacts except that one phenyl group stacks with the indole ring of Trp105, thus corroborating well with the observed better electron density for this ring (Fig. 6a). The centroids of the atomic coordinates of the indole ring and the benzyl group of the inhibitor are 4.0 Å apart, a typical distance for the stacking interaction.

Fig. 6.

(a) Stereo view of the initial |Fo| − |Fc| electron density map (blue) contoured at the 3σ level and the final 2| Fo| − |Fc| electron density map (pink) contoured at the 1σ level for the inhibitor. The inhibitor is shown by stick representation with carbon atoms in cyan. The catalytic triad residues Asp104, Asp302, and His333 are shown by stick model with carbon atoms in green. Tyr164 and Tyr272 that provide electrophilic assistance during the hydrolytic reaction are shown by stick model with carbon atoms in cyan. Trp105 that makes stacking interactions with one phenyl group of the inhibitor is also shown by stick model with carbon atoms in green. (b) Stereo view of the EHB residues that interact with the inhibitor (distance cutoff, 4.0 Å) are shown by stick representation with carbon atoms in yellow. The catalytic water is shown by a red sphere. Hydrogen bonds are shown by green dotted lines.

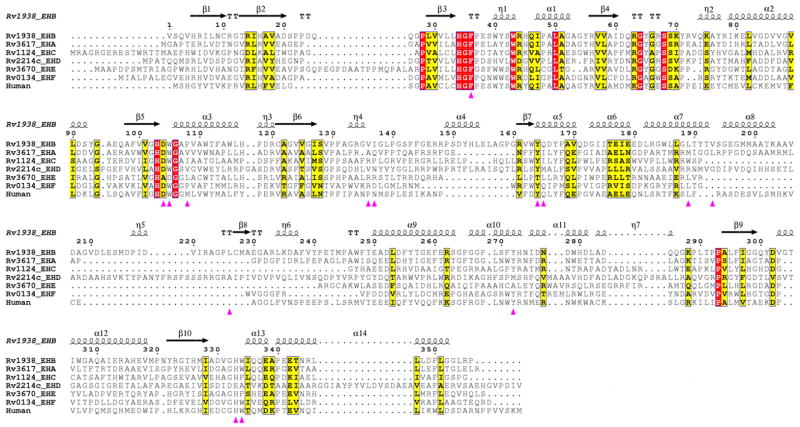

Sequence alignment

A sequence comparison among the six Mtb EHs and human sEH suggests that Asp104, His333, and Asp302 are conserved across all except that Asp104 is not conserved in EHE and Asp302 and His333 are not conserved in EHD (Fig. 7). Among the six Mtb EHs, EHD has the longest polypeptide chain (592 amino acids), and prediction shows that it has a small transmembrane domain (residues 164–186). This probably indicates that EHD and EHE belong to another class of EH. Among the residues lining the inhibitor binding pocket, only Phe36 is conserved across six Mtb and human EHs. Since all other residues that interact with the inhibitor are different, there may be a variation in the substrate specificity among the Mtb EHs.

Fig. 7.

Sequence alignment among six Mtb EHs and human sEH. Conserved residues are shown in red boxes. The secondary structural elements correspond to that of Mtb EHB structure. Residues that border the Mtb EHB active site are shown by magenta triangles. Residues 1–405, of the total 592 of Mtb EHD, are shown, since there are no corresponding matching residues beyond 405 in the other EHs.

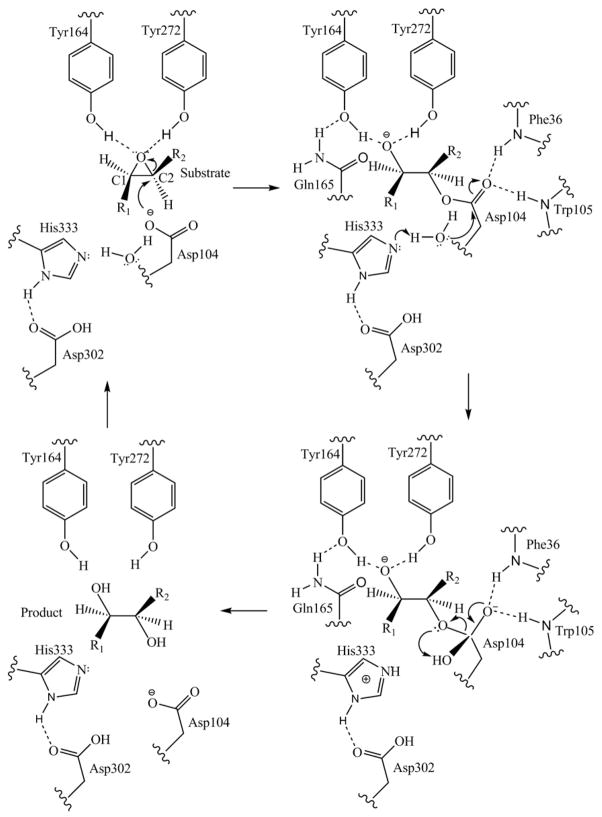

The hydrolytic mechanism of Mtb EHB

There are two main steps in this proposed mechanism. The first is associated with the epoxide ring opening as a result of the nucleophilic attack by the carboxylate of Asp104 on the “C2” atom of the epoxide (Fig. 8). The resulting covalently attached intermediate is an ester. Hydrolysis of this ester constitutes the second step of the reaction.

Fig. 8.

A schematic picture showing the reaction mechanism of how Mtb EHB hydrolyses the epoxide substrate. The reaction proceeds by the nucleophilic attack by Asp104.

Based on the Mtb EHB structure, the structure of the bound inhibitor 7 discussed above and the previously determined structures of sEHs from various other organisms,16–19 we propose that the phenolic hydroxyl groups of Tyr164 and Tyr272 form an oxyanion stabilizing unit to provide electrophilic assistance for ring opening of the epoxide (top right of Fig. 8). The hydroxyl groups of Tyr164 and Tyr272 would be oriented in line and hydrogen-bonding with the two lone pair electrons on the epoxide ring oxygen atom. The ionized carboxylate of Asp104 acts as a nucleophile to attack the epoxide ring carbon atom forming a covalently attached ester bond with the substrate (top right of Fig. 8). Associated with this attack, the polarized epoxide oxygen–carbon bond would break with the negative charge on the resulting oxyanion stabilized by the two phenolic OH groups. Whether one of these OH groups actually donates a proton to the substrate oxyanion is not determinable. The proton needed to form the product hydroxyl group on C1 could come from the second step in the mechanism, the hydrolysis of the ester.

In the second step, the water molecule is activated to a strongly nucleophilic hydroxide ion so that it attacks the carbonyl carbon atom of the ester intermediate. This nucleophilic attack is assisted by the general base function of the imidazole of His333. In addition, the two main-chain NH groups of Phe36 and Tyr105 form a second oxyanion hole to stabilize the negatively charged oxygen of the tetrahedral intermediate (bottom right of Fig. 8). Collapse of this intermediate results in the cleavage of the ester bond to produce the hydroxide on C2 of the substrate (bottom left of Fig. 8). The second possible source for the proton needed to produce the C1 hydroxyl is the dissociation of the protonated imidazole that resulted from its general base function on the water.

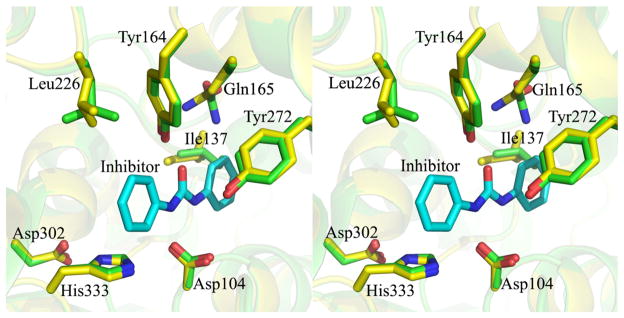

Conformational changes upon inhibitor binding and mechanism of inhibition

Upon inhibitor binding, the overall structure of Mtb EHB does not undergo major conformational changes as is evident from the small rmsd value (0.20 Å for 328 Cα pairs) upon superimposing the free and inhibitor-bound Mtb EHB structures. The conformations of catalytic residues Asp104, Tyr164, Tyr272, Asp302, and His333 are essentially the same between the free and inhibitor-bound structures. This suggests that these catalytic residues remain relatively rigid upon substrate binding. However, some of the residues in the inhibitor binding site do undergo subtle structural rearrangement. Notably, the side chain (Cγ1, Cγ2, and Cδ1) of Ile137 rotates approximately 120° about its Cα–Cβ bond in order to accommodate the inhibitor (Fig. 9). More importantly, the carboxamide moiety of Gln165 rotates about its Cβ–Cγ bond so that the Nε2 atom can form a strong hydrogen bond (2.8 Å) with the Oη of Tyr164. The Nε2 atom of Gln165 of the inhibitor-bound structure moves approximately 2 Å towards Tyr164 with respect to its position in the free enzyme. Also, the side chain ( Cγ, Cδ1, and Cδ2) of Leu226 exhibits a conformational change about its Cα–Cβ bond upon inhibitor binding. The Cγ, Cδ1, and Cδ2 atoms of Leu226 are not well defined in the electron density in either of the structures. These flexible residues—Ile137, Gln165, and Leu226—belong to the cap domain. This is another line of evidence that the cap domain is inherently flexible. As expected, the catalytic water molecule, shown in Fig. 5, is conserved between the free and inhibitor-bound structures. Since the inhibitor binds competitively to the active site, in a similar manner as would a substrate of EHB, and makes hydrogen bonds to the nucleophile Asp104 and to the electrophilic groups Tyr164 and Tyr272, the inhibitor freezes the enzyme into an inactive form.

Fig. 9.

Stereo view of superimposition, showing the conformational changes in the active-site pocket, between the Mtb free (carbon atoms in green) and inhibitor-bound (carbon atoms in yellow) EHB structures. The rmsd in the 328 Cα coordinates between these structures is 0.20 Å.

Conclusions

TB poses a global threat to the human population. The identification of the various factors, through a multidisciplinary approach, that are responsible for the survival of Mtb in host macrophages would not only help in a more complete understanding of the pathogenesis of this bacterium but also would help in designing small-molecule inhibitors against these factors. In light of the fact that mammalian EHs have been targeted for development of drugs for various diseases, Mtb EHs that are involved in a detoxification pathway could be among the potential drug targets for the development of antituberculars. To have more insight into the detailed role of these enzymes in Mtb pathogenesis, knocking out the EH gene(s) from the Mtb genome and examining the effect of these genes on the bacterial growth in cell colony would be interesting. The EHB crystal structure represents the first structure of an α/β hydrolase type from Mtb. Although the overall structure of Mtb EHB is similar to that of the human sEH, there are differences in the details of the structures. In particular, Mtb EHB has a longer loop that connects the hydrolase and the cap domains than does human sEH. The loop may be vital for controlling the substrate specificity of Mtb EHB. This detailed structural information can be used in the design of other small-molecule inhibitors specific only to Mtb. Since similar urea-based inhibitors inhibit the human and murine EHs that have been targeted for the regulation of blood pressure, cancer progression, and the onset of several other diseases, the carbonilide inhibitor against Mtb EHB represents an excellent lead compound to develop enhanced structural-based inhibitors against these EHs. Such inhibitors could lead to novel means to treat TB.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, purification, and crystallization

The details of cloning, expression, purification, and crystallization of Mtb EHB have been published elsewhere.23 Briefly, the plasmid containing Rv1938 and an N-terminal hexahistidine tag was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen). The expression was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. Rv1938 was purified by the metal-affinity chromatography method using a Ni-charged immobilized column (GE Healthcare). Crystals were grown in hanging drops containing equal volumes (1 μl) of the protein solution (20% isopropanol, 0.2 M CaCl2, and 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.6) and the reservoir solutions and equilibrated against 1 ml of the reservoir solution (20% isopropanol, 0.2 M MgCl2, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5). The EHB/inhibitor complex crystals were produced by soaking the unbound EHB crystals in 1 mM solutions of the carbanilide inhibitor 7 (Table 3).

Enzyme assays

The EH activity was measured using as substrates compounds 1 to 6 (Table 2), racemic [3H]trans-1,3-diphenylpropene oxide (1), [3H]trans-stilbene oxide (2), and [3H]cis-stilbene oxide (3), as described previously.24 Briefly, 1 μl of a 5 mM solution of tritiated substrate in 1% ethanol was added to 100 μl of enzyme preparation in sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin ([S] final=50 μM; 12,000 dpm/assay). The enzymes were incubated at 30 °C for 10 min, and the reaction was quenched by addition of 60 μl of methanol for 1 (none for 2 and 3) and 200 μl of isooctane for 1 (250 μl for 2 and 3). This treatment extracts the remaining epoxide from the aqueous phase. The activity was followed by measuring the quantity of radioactive diol formed in the aqueous phase using a liquid scintillation counter (Wallac Model 1409, Gaithersburg, MD). Assays were performed in triplicate. Racemic 3H-labeled juvenile hormone III (4) and 14C-labeled cis-9,10-epoxystearic acid (5) EH activities were measured as described.25,26 Activity with the fluorescent substrate cyano(6-methoxy-naphthalen-2-yl) methyl trans-[(3-phenyloxiran-2-yl)methyl] carbonate (6) was measured as described,21 using 6-methoxy-naphthal-dehyde as standard.

Inhibitor assay

IC50 values were determined using compound 6 as the substrate.21 Mtb EHB ([E] ~30 nM; 1.5 g/ml) was incubated with inhibitors ([I]=5–100,000 nM) for 5 min in BisTris–HCl buffer (25 mM, pH 7.0, containing 0.1 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin) at 30 °C prior to substrate introduction ([S]=5 μM). Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring the appearance of fluorescent of 6-methoxy-naphthaldehyde (λex 330 nm and λem 465 nm) on a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Assays were performed in triplicate. By definition, IC50 values are concentrations of inhibitor that reduce enzyme activity by 50%. IC50 values were determined by regression of at least five datum points, with a minimum of two datum points in the linear region of the curve on either side of the IC50 values.

Data collection, structure solution, and refinement

X-ray data from the native and inhibitor-soaked crystals of Rv1938 were collected at beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Berkeley, CA, and at beamline 9.2 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), Stanford, CA, respectively. In both cases, data sets were integrated and scaled by the programs HKL2000 and SCALEPACK.27 The data collection and data processing statistics are given in Table 4. The structure was solved by the molecular replacement method with the program PHASER28 using the C-terminal domain (residues 245–541) of the murine EH structure (Protein Data Bank ID 1EK1, 3.1 Å resolution) as the search model. A difference Fourier map, |FPI| − |FP|, αcalc (|FPI| and |FP| are the structure factor amplitudes of the protein–inhibitor complex and of the apoprotein, respectively), permitted the initial positioning of the inhibitor molecule into the difference electron density. Structure refinement was carried out using the program CNS 1.1.29 Both structures reported in this paper were refined in the same manner. Initially, the structures were subjected to 50 cycles of rigid-body refinement followed by simulated annealing, then by positional and individual B-factor refinements. Model building, based on electron density maps (2|Fo| − |Fc| at 1σ and |Fo| − |Fc| at 3σ contour levels), was performed wherever necessary using the program XtalView.30 Bulk solvent corrections and anisotropic B-factor scaling were incorporated during the refinement. The stereochemical acceptability of the structures were validated using the program PROCHECK31 that uses Engh and Huber stereochemistry dictionary.32 The refinement statistics are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Native Rv1938 | Inhibitor complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal | ||

| Space group | P41212 | P41212 |

| a=b (Å) | 66.3 | 66.4 |

| c (Å) | 157.1 | 156.8 |

| α = β = γ (°) | 90 | 90 |

| Z | 8 | 8 |

| Matthews coefficient (Å3/Da) | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Solvent content (%) | 42.8 | 44.2 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.35 | 0.30 |

| Data collection | ALS | SSRL |

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 |

| Detector | ADSCQ315 | ADSCQ325 |

| No. of crystals | 1 | 1 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 100 | 100 |

| Wave length (Å) | 1.1159 | 0.9793 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.1 | 50–2.4 |

| High-resolution shell (Å) | 2.18–2.10 | 2.49–2.40 |

| Unique reflections | 20,701 (1663) | 14,403 (1386) |

| Multiplicity | 6.4 (3.3) | 7.7 (7.1) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 23.4 (2.1) | 14.8 (2.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 97.4 (80.4) | 99.8 (99.7) |

| Rsym (%)a | 7.0 (49.2) | 12.7 (57.0) |

| Rr.i.m. (%)b | 7.6 (58.9) | 13.6 (61.5) |

| Rp.i.m. (%)c | 3.0 (32.4) | 4.9 (23.1) |

| Overall B-factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 35.8 | 41.5 |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.10 | 50–2.40 |

| Unique reflections (working/test) | 19,663/1038 | 13,679/724 |

| Roverall/Rworking/Rfree d | 0.225/0.235/0.276 | 0.202/0.209/0.256 |

| No. of atoms (protein/solvent/acetate/inhibitor) | 2708/128/36/— | 2708/120/12/16 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) of | ||

| All atoms | 52.6 | 40.3 |

| Protein atoms | 52.4 | 40.4 |

| Solvent atoms | 53.6 | 38.1 |

| Acetate atoms | 65.4 | 48.6 |

| Inhibitor atoms | — | 40.6 |

| rmsds from ideality | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Dihedral angles (°) | 22.6 | 22.2 |

| Improper angles (°) | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored regions (%) | 86.7 | 88.2 |

| Additional allowed regions (%) | 11.5 | 10.0 |

| Generously allowed regions (%) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 0.7 (Ser128, Val136) | 0.7 (Ser128, Val136) |

Values within parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = ΣhΣi(|Ii(h) − 〈I(h)〉|)/ΣhΣiIi(h), where Ii(h) is the ith intensity measurement and 〈I(h)〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of Ii(h).

Rr.i.m. (redundancy-independent merging R-factor)=Σh[N/(N − 1)]1/2Σi(|Ii(h) − 〈I(h)〉|)/ΣhΣiIi(h).

Rp.i.m. (precision-indicating merging R-factor)= Σh[1/(N − 1)]1/2Σi(|Ii(h) − 〈I(h)〉|)/ΣhΣiIi(h), where N is redundancy.

Roverall, Rworking, and Rfree = Σh(|F(h)obs| − |F(h)calc|)/Σh|F (h)obs| for all reflections and for reflections in the working and test sets. Rfree was calculated using 5% of data.

Figure preparation and computation

All figures, except Figs. 7 and 8, were prepared by the program PYMOL‡. Sequence alignment was performed by the program CLUSTALW33 and Fig. 7 was prepared using the program ESPript.34 Figure 8 was drawn using the program Chemdraw§. Structural superimpositions were performed and active-site pocket volumes were calculated using the programs ALIGN35 and CASTp,36 respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ernst Bergmann, Jonathan Parrish, and Vera Jbanova for their help during the data collection on beamline 8.3.1. of the ALS under an agreement with the Alberta Synchrotron Institute (ASI). The ALS is operated by the Department of Energy and supported by the National Institutes of Health. Beamline 8.3.1 is funded by the National Science Foundation, the University of California, and Henry Wheeler. The ASI synchrotron access program is supported by grants from the Alberta Science and Research Authority, the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, and Western Economic Diversification of Canada. The data from enzyme/inhibitor complexes were collected at beamline 9.2 of the SSRL. M.N.G.J. is grateful for a Canada Research Chair in Protein Structure and Function. This work was partially funded by NIEHS Merit Award R37 ES02710.

Abbreviations used

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- EH

epoxide hydrolase

- TB

tuberculosis

- Mtm

Mycobacterium marinum

- LEH

limonene EH

- sEH

soluble EH

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.030

Protein Data Bank accession codes

The atomic coordinates and the structure factors for the free Mtb EHB and Mtb EHB bound to the inhibitor structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank|| with the accession codes 2E3J and 2ZJF, respectively.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Program. 2008 http://www.who.int/gtb/

- 2.Murillo AC, Li HY, Alber T, Baker EN, Berger JM, Cherney LT, et al. High throughput crystallography of TB drug targets. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:127–139. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacchettini JC, Rubin EJ, Freundlich JS. Drugs versus bugs: in pursuit of the persistent predator Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:41–52. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman JW, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Epoxide hydrolases: their roles and interactions with lipid metabolism. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44:1–51. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmelzer KR, Kubala L, Newman JW, Kim IH, Eiserich JP, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a therapeutic target for acute inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9772–9777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503279102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung O, Brandes RP, Kim IH, Schweda F, Schmidt R, Hammock BD, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase is a main effector of angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:759–765. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153792.29478.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Epoxide hydrolases: mechanisms, inhibitor designs, and biological roles. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:311–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang SH, Morisseau C, Do Z, Hammock BD. Solid-phase combinatorial approach for the optimization of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:577–5773. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang SH, Tsai HJ, Liu JY, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Orally bioavailable potent soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3825–3840. doi: 10.1021/jm070270t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson P, Unge T, Cronin A, Arand M, Bergfors T, Jones TA, Mowbray SL. Structure of an atypical epoxide hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis gives insights into its function. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arand M, Hallberg BM, Zou J, Bergfors T, Oesch F, van der Werf MJ, et al. Structure of Rhodococcus erythropolis limonene-1,2-epoxide hydrolase reveals a novel active site. EMBO J. 2003;22:2583–2592. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Etr SH, Subbian S, Cirillo SL, Cirillo JD. Identification of two Mycobacterium marinum loci that affect interactions with macrophages. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6902–6913. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.6902-6913.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi SM, Pandey AK, Capite N, Fortune SM, Rubin EJ, Sassetti CM. Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11760–11765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603179103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argiriadi MA, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Christianson DW. Detoxification of environmental mutagens and carcinogens: structure, mechanism, and evolution of liver epoxide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10637–10642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez GA, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Christianson DW. Structure of human epoxide hydrolase reveals mechanistic inferences on bifunctional catalysis in epoxide and phosphate ester hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4716–4723. doi: 10.1021/bi036189j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nardini M, Ridder IS, Rozeboom HJ, Kalk KH, Rink R, Janssen DB, Dijkstra BW. The x-ray structure of epoxide hydrolase from Agrobacterium radiobacter AD1. An enzyme to detoxify harmful epoxides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14579–14586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou J, Hallberg BM, Bergfors T, Oesch F, Arand M, Mowbray SL, Jones TA. Structure of Aspergillus niger epoxide hydrolase at 1.8 Å resolution: implications for the structure and function of the mammalian microsomal class of epoxide hydrolases. Struct Fold Des. 2000;8:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazumdar PA, Hulecki J, Cherney MM, Garen CR, James MN. X-ray crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis haloalkane dehalogenase Rv2579. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morisseau C, Beetham JK, Pinot F, Debernard S, Newman JW, Hammock BD. Cress and potato soluble epoxide hydrolases: purification, biochemical characterization and comparison to mammalian enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;378:321–332. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones PD, Wolf NM, Morisseau C, Whetstone P, Hock B, Hammock BD. Fluorescent substrates for soluble epoxide hydrolase and application to inhibition studies. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswal BK, Garen G, Cherney MM, Garen C, James MN. Cloning, expression, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray studies of epoxide hydrolases A and B from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr F. 2006;62:136–138. doi: 10.1107/S1744309106000637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Measurements of soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) activity. In: Bus JS, Costa LG, Hodgson E, Lawrence DA, Reed DJ, editors. Techniques for Analysis of Chemical Biotransformation. Current Protocols in Toxicology. Supplement 33. John Wiley and Sons; New Jersey: 2007. Aug, pp. 4.23.1–4.23.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mumby SM, Hammock BD. A partition assay for epoxide hydrases acting on insect juvenile hormone and an epoxide-containing juvenoid. Anal Biochem. 1979;92:16–21. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90619-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borhan B, Mebrahtu T, Nazarian S, Kurth MJ, Hammock BD. Improved radiolabeled substrates for soluble epoxide hydrolase. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:188–200. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McRee DE. XtalView/Xfit—a versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol. 1999;125:156–165. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski RJ, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structure. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignments through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gouet P, Robert X, Courcelle E. ESPript/ENDscript: extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3320–3323. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen GH. ALIGN: a program to superimpose protein coordinates, accounting for insertions and deletions. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1160–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang J, Edelsbrunner H, Woodward C. Anatomy of protein pockets and cavities: measurement of binding site geometry and implications for ligand design. Pro Sci. 1998;7:1884–1897. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.