Abstract

The membrane-bound structure, lipid interaction, and dynamics of the arginine-rich β-hairpin antimicrobial peptide PG-1 as studied by solid-state NMR is highlighted here. A variety of solid-state NMR techniques, including paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, 1H and 19F spin diffusion, dipolar recoupling distance experiments, and 2D anisotropic-isotropic correlation experiments, are used to elucidate the structural basis for the membrane disruptive activity of this representative β-hairpin antimicrobial peptide. We found that PG-1 structure is membrane dependent: in bacteria-mimetic anionic lipid membranes the peptide forms oligomeric transmembrane β-barrels, whereas in cholesterol-rich membranes mimicking eukaryotic cells the peptide forms β-sheet aggregates on the surface of the bilayer. PG-1 causes toroidal pore defects in the anionic membrane, suggesting that the cationic arginine residues drag the lipid phosphate groups along as the peptide inserts. Mutation of PG-1 to reduce the number of cationic residues or to change the arginine guanidinium structure significantly changes the degree of insertion and orientation of the peptide in the lipid membrane, resulting in much weaker antimicrobial activities.

Antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small cationic peptides produced by the innate immune system of many animals and plants to kill a broad spectrum of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses 1. AMPs have a diverse range of secondary structures. For instance, magainin from the African clawed frog 2 and LL-37 from human 3 are α-helical peptides. Tachyplesins from the horseshoe crab 4 and protegrins from porcine leukocytes 5 are antiparallel β-hairpin peptides constrained by multiple disulfide bonds. Aromatic-rich peptides such as indolicidins and tritrpticin adopt turn-rich structures 6. Despite this structural diversity, most antimicrobial peptides share the common feature that their cationic residues are spatially well separated from the hydrophobic residues, thus making the overall structure of these molecules amphipathic. AMPs distinguish the microbial cells from eukaryotic cells by taking advantage of the difference that microbial cell membranes have a significant percentage of anionic phospholipids and no cholesterol, while eukaryotic cell membranes contain mostly zwitterionic phospholipids and a high level of cholesterol 7. These fundamental differences are particularly pronounced in the outer leaflet of the cell membranes, which the peptides interact with upon first contact 8, 9.

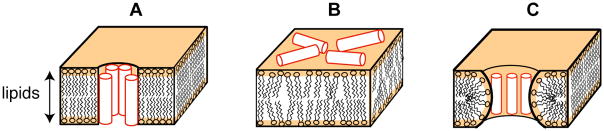

While it is generally agreed that membrane disruption is the main modus operandi of AMPs, distinct peptide-lipid interactions have been observed for various AMPs, leading to three main models of antimicrobial mechanism. In the “barrel-stave” model (Fig. 1A), the peptides aggregate into transmembrane (TM) helical bundles that insert into the bilayer to form pores, which subsequently lyse the cell. This model was used to explain the step-wise conductivity increases in alamethicin – containing membranes 10, 11. In the “carpet” model (Fig. 1B), the peptides accumulate on the bilayer surface with the hydrophobic face embedded shallowly in the hydrophobic region of the membrane, while the positive charges are directed toward the hydrophilic water. When the peptide concentration exceeds a threshold, the bilayers are disrupted into micelles, thus killing the cell. This model was initially proposed based on studies of dermaseptin 12. In the toroidal pore model (Fig. 1C), the aggregating peptides cause lipid disorder such that the two leaflets of the bilayer merge to form a torus-shaped pore. This model was proposed to explain the large water-filled cavities 13 and increased lipid flip-flop rate 14 caused by magainin.

Fig. 1.

Three models of membrane disruption by antimicrobial peptides. (A) Barrel-stave model. (B) Carpet model. (C) Toroidal pore model.

Protegrin-1 (PG-1) is one of a family of peptides isolated from porcine leukocytes 15. It possesses broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and some enveloped viruses 5. Its minimum inhibitory concentrations are a few micrograms per milliliter 16. PG-1 has eighteen amino acids, six of which are arginines (Arg) (Fig. 2A). Two disulfide bonds constrain the molecule to a β-hairpin fold, with the β-strand region containing residues 4–8 and 13–17 and the β-turn containing residues 9–12. PG-1’s secondary structure is representative of many β-hairpin AMPs; thus the peptide is a good model system for understanding the interaction of this class of AMPs with lipid membranes. An extensive structure–activity relationship (SAR) study has been conducted on several hundred protegrin analogues 17. It was found that the overall amphiphilicity, charge density, intermolecular hydrogen-bonding capability and the hairpin fold are more important to activity than the presence of specific amino acids and stereochemistry. Lipid vesicle leakage assays 18, 19 and neutron diffraction of oriented lipid bilayers 20 indicated that PG-1 carries out its function by forming pores in the microbial cell membrane. However, the high-resolution structure of the peptide and its supramolecular assemblies at these pores was not known. Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) spectroscopy is an excellent technique to determine the atomic-resolution structure of membrane-bound peptides and proteins 21, 22. We have conducted an extensive SSNMR study of the interaction of PG-1 with lipids and the topological structure of PG-1 in lipid membranes of different compositions, which reveal the origin of PG-1’s antimicrobial activity 23.

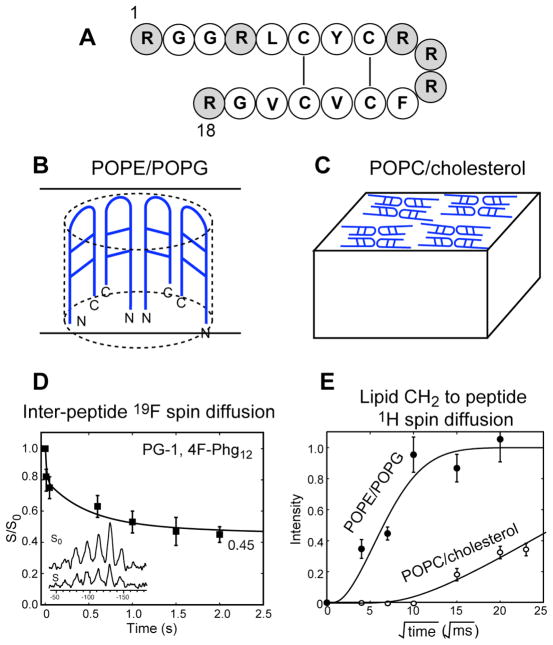

Fig. 2.

(A) Amino acid sequence of PG-1 with the Arg residues shaded. (B) The depth of insertion, orientation and oligomeric structure of PG-1 in anionic POPE/POPG membranes. (C) The depth of insertion and oligomeric structure of PG-1 in neutral POPC/cholesterol membranes. (D) Representative 19F spin diffusion data that yielded the oligomeric structure of PG-1 in the lipid membrane 29. (E) Representative lipid-protein 1H spin diffusion data that yielded the transmembrane insertion of PG-1 in anionic membranes and surface-bound state in neutral cholesterol-containing membranes 29.

Depth and orientation of β-hairpin antimicrobial peptides in lipid membranes

The insertion and orientation of β-sheet membrane proteins in lipid bilayers have not been well studied compared to their α-helical counterparts. We demonstrated a method to determine the depths of insertion of membrane peptides that utilizes the paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) effect. Paramagnetic ions such as Mn2+ readily bind to the surface of lipid bilayers and enhance nuclear spin T2 relaxation in a distance-dependent fashion 24, 25. The closer the nuclei are from the membrane surface, the faster the T2 relaxation, and the lower the NMR intensity. Thus, intensity decreases of the protein compared to a control sample without the paramagnetic ions reflect the depths of individual residues from the bilayer surface. Further, one can calibrate the peptide depths by comparing with the lipid signals, since the depths of lipid segments are well known from X-ray and neutron diffraction data 26. Applying this technique to PG-1 in DLPC bilayers, we found that residues at the N-terminus and the β-turn of the peptide experience strong PRE whereas residues in the middle of the strands experience weaker PRE effects. Thus the β-hairpin peptide is fully inserted across the lipid bilayer 24.

The lipid-calibrated PRE technique is most applicable to mobile membrane peptides. To determine the depths of immobile molecules, which can be either large membrane proteins or highly oligomerized membrane peptides, 1H spin diffusion from the lipids to the protein is a more suitable technique. In this experiment, the lipid chain protons transfer their magnetization to the protein in a distance-dependent fashion and is detected through the protein 13C signals. The lipid-protein 1H-13C cross peak intensities depend on the depth of insertion of the protein. The intensity buildup as a function of the spin diffusion mixing time yields semi-quantitative distances (± 2 Å) of the protein from the center of the bilayer 27. Using this technique, we found that PG-1 is in close contact with the lipid methyl groups both in zwitterionic 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membranes 28 and in mixed anionic membranes containing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol (POPG) 29, 30 (Fig. 2B, E). In contrast, PG-1 is ~20 Å from the hydrophobic center of POPC/cholesterol membranes, since the lipid chain-peptide cross peaks are very weak even at long mixing times (Fig. 2C, E). Thus, the membrane composition has a significant effect on PG-1 insertion: the bacteria-mimetic anionic membrane POPE/POPG allows PG-1 insertion, while the eukaryotic POPC/cholesterol membrane prevents PG-1 insertion.

Orientation information complements depth measurements in elucidating the topology of antimicrobial peptides in lipid bilayers. The orientations of α-helical membrane proteins in lipid bilayers have been well studied using 2D separated-local field (SLF) NMR, specifically correlating the 15N chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) with the 15N-1H dipolar coupling on macroscopically aligned samples 31, 32. This strategy is also applicable to β-sheet membrane proteins but with very different characteristic spectral patterns 33–35. The reason is that the N-H bonds, which correspond to the main direction of the 15N chemical shift tensor and the N-H dipolar tensor, are not along the main molecular axis, the β-strand axis, of β-sheet peptides. This makes the 15N CSA and N-H dipolar tensors not very diagnostic of the β-strand orientation, unless a sufficient number of 15N constraints are measured. In comparison, the 13CO chemical shift tensor is ideally sensitive to the β-sheet geometry: its x principal axis points along the β-strand axis and its z principal axis points along the normal of the β-sheet plane. Thus, 13CO CSA measurements on aligned β-sheet membrane peptides give relatively clear orientation information. We used both the 2D 15N SLF technique and the 1D 13CO CSA experiment to determine the orientations of several β-hairpin AMPs. For the cyclic β-hairpin AMP retrocyclin, the 2D 15N SLF spectra indicated a TM orientation of the peptide in DLPC bilayers 35. For PG-1, 13CO and 15N CSAs constrained the peptide to a tilted orientation in DLPC bilayers, with the strand axis ~55° from the bilayer normal 36. For the horseshoe crab β-hairpin AMP tacheplesin-1 (TP-I), 13CO and 15N CSAs indicate an in-plane orientation, with a angle of ~20° between the β-sheet plane and the membrane surface 37.

Since AMPs tend to disrupt lipid membranes, macroscopically aligned bilayers that underlie the above orientation-dependent spectra are often difficult if not impossible to prepare. Even when aligned, the membrane composition that allows the alignment may not be the most biological. To overcome this difficulty, we exploited the fact that many small membrane peptides undergo uniaxial rotation around the bilayer normal at rates faster than the CSA and dipolar interactions. Under this fast uniaxial rotation, it can be shown that the 0° (90°) frequency of the motionally averaged spectra of an unoriented sample is identical to the frequency of an oriented sample whose alignment axis is parallel (perpendicular) to the magnetic field 37, 38. Thus, if the peptide is uniaxially mobile, then one can avoid alignment altogether and use powder samples and magic-angle spinning (MAS) experiments to determine the peptide orientation. This approach was demonstrated on PG-1, TP-I, and an α-helical membrane peptide, the M2 peptide of influenza A virus 37, 38. The presence of fast uniaxial rotation can be verified from the powder patterns of CSA tensors that are large and non-uniaxial in the rigid limit 39. If the powder patterns are not only narrowed from the rigid-limit value but also have an asymmetry parameter of 0, then it is a strong indication that the molecule undergoes fast uniaxial rotation.

Oligomeric Structure of β-hairpin antimicrobial peptides

Most models of antimicrobial action invoke peptide oligomerization as a prerequisite for membrane disruption. SAR studies of PG-1 showed that linearized mutants and mutants that eliminate potential hydrogen bonds between β-hairpins have weaker activities 17. A solution NMR study of PG-1 in dodecylphosphocholine micelles 40 showed 1H-1H NOE’s indicative of antiparallel dimers where the C-terminal strand lines the dimer interface. But micelles tend to impose curvature strains onto peptides and may not reflect the oligomeric state of the peptide in lipid bilayers. We found that PG-1 backbone is immobilized in POPC bilayers in the liquid-crystalline phase, which is not possible if the peptide is monomeric 28. Quantitative 19F spin diffusion experiments (Fig. 2D) showed that PG-1 is indeed oligomerized in membranes with lipid chain lengths of 16–18 41, 42. In POPC and POPE/POPG bilayers, PG-1 assembles with the same strands lining the intermolecular interface and with each 19F in a two-spin environment. Further, the β-hairpins in this …NCCNNCCN… assembly are parallel instead of antiparallel, based on intermolecular 1H-13C, 13C-19F, and 13C-15N distance experiments 43. Since PG-1 is also transmembrane in the same bacteria-mimetic membranes based on 1H spin diffusion experiments, and leakage assays indicate pores with a diameter of ~20 Å, we conclude that PG-1 oligomerizes into TM β-barrels of 8–10 molecules 29 (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the peptide also forms structured aggregates similar to amyloid fibrils in the absence of lipid bilayers, and the intermolecular packing was found by 2D 13C-13C correlation experiments to be parallel with like strands at the interfaces 44. Thus the fibrilized PG-1 structure is very similar to the membrane-bound structure. In the POPC/cholesterol membrane, 19F spin counting experiments revealed larger spin clusters of at least 4, indicating that the peptide aggregates more extensively. Moreover, lipid-to-peptide 1H spin diffusion experiments revealed that PG-1 lies on the surface of the cholesterol-rich membrane. Thus, PG-1 assembles into extended β-sheets on the surface of eukaryotic cell membranes (Fig. 2C).

Guanidinium-phosphate complexation between antimicrobial peptides and lipids

Most antimicrobial peptides are rich in Arg. However, the exact role of cationic residues in antimicrobial activities had not been elucidated with high-resolution structural input. SAR studies indicated that protegrin mutants with fewer Arg residues have weaker activities by as much as an order of magnitude compared to wild-type PG-1 17. In general, the insertion of charged residues into the hydrophobic part of the lipid bilayer is energetically unfavorable. Measurement of the free energy 45, 46 of transferring peptides from water to lipid bilayers using an endoplasmic reticulum translocon system gave positive free energies of about +2.5 kcal/mol for each Arg and Lys residue 47. Despite this free energy cost, helical peptides containing multiple Arg residues have been found to insert into the lipid bilayer 48. Molecular dynamics simulations suggested that Arg-rich peptides can insert into the membrane with the help of membrane thinning, the formation of Arg-water hydrogen bonds, and the formation of Arg-phosphate hydrogen bonds 49, 50.

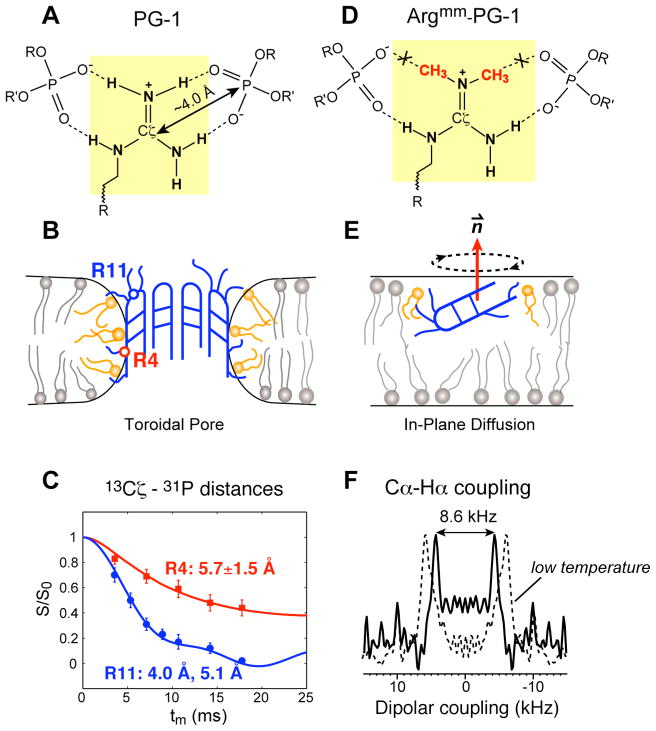

The TM topology of PG-1 in non-cholesterol membranes would put some residues such as Arg4 in the center of the bilayer, with apparently high free energy penalty. To understand how this happens, we measured the 13C-31P distances between Arg residues and lipid phosphate groups. The TM topology predicts Arg’s at the two ends of the molecule to be close to the 31P while Arg4 and other strand interior residues to be far from 31P. Surprisingly, we found that Arg4 has similarly short 13C-31P distances as Arg11 at the β-turn. All distances fall within 4.0 and 6.5 Å 30. The shortest distance, 4.0 Å, is found between Arg11 Cζ and 31P (Fig. 3C). Since Cζ is surrounded by NH groups while 31P is surrounded by oxygen atoms, this short distance means that the guanidinium group must form hydrogen bonds with the PO4 group (Fig. 3A). Further, 13C-31P distances for two consecutive residues along the β-strands indicate that the 31P plane cannot be perpendicular to the TM hairpin but must be parallel to it. Thus, some lipid molecules must turn around to embed their headgroups into the hydrophobic region of the bilayer. This indicates toroidal pore defects created by PG-1 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) Guanidinium-phosphate complexes between PG-1 Arg residues and the lipid headgroups. (B) Toroidal pore model of PG-1 in anionic lipid membranes. For clarity, only half of the PG-1 β-barrel is shown. (C) Representative 13C-31P distance data of PG-1 that yielded the toroidal pore model 30. (D) A dimethylated guanidinium group removes two potential hydrogen bonds with the lipid phosphates. (E) The orientation and depth of insertion of Argmm-PG-1 in the anionic membrane 39. (F) Representative C-H dipolar coupling data that showed the dynamic structure and orientation of Argmm-PG-1.

The driving force for this toroidal pore formation is most likely guanidinium-phosphate interactions. The guanidinium ion is responsible for most of Arg’s non-covalent interactions and is known to form stable complexes with oxyanions such as phosphates, sulfates and carboxylates 51. The short distances between PG-1 Arg residues and lipid phosphates are thus not too surprising. The nature of this guanidinium-phosphate interaction is partly electrostatic, since the 13C-31P distances are ~2.0 Å longer in zwitterionic POPC membranes than in anionic POPE/POPG membranes 44. The electrostatic nature is also supported by the findings that when the number of Arg residues was reduced from six to three, the mutant PG-1 inserted less deeply into the membrane and exhibited longer distances to 31P (7.0–9.5 Å) 52. In zwitterionic POPC membranes, the Arg-reduced mutant is completely on the membrane surface, while in the 25% anionic POPC/POPG membranes, the mutant peptide is still about 8 Å from the membrane center.

The second factor stabilizing the guanidinium-phosphate complex is N-H···O=P hydrogen bonding. This is shown by an experiment where all Arg residues in PG-1 were mutated to dimethylated Arg (Fig. 3D), thereby removing two potential hydrogen bond donors per guanidinium ion. This Argmm-PG-1 peptide showed a three-fold reduction of antimicrobial activity, less membrane disorder as judged by 31P NMR lineshapes, and longer peptide-lipid 13C-31P distances. Argmm-PG-1 is also highly dynamic 39, suggesting that it is monomeric in the membrane, in contrast to the immobilized and oligomerized wild-type PG-1. The dynamics is uniaxial and present for multiple residues in the peptide, thus it is likely whole-body rotational diffusion around the bilayer normal. We thus determined the orientation of Argmm-PG-1 by measuring motionally averaged Cα-Hα dipolar couplings of two strand residues (Fig. 3F) using unoriented MAS samples. Analysis of the orientation-dependent backbone bond order parameters indicates that the strand axis is tilted by 120° from the bilayer normal and the β-sheet plane is parallel to the bilayer normal 39 (Fig. 3E). Thus Argmm-PG-1 dips into the bilayer with its β-sheet plane meeting the least resistance, and this insertion mode is completely different from the wild-type peptide. It is striking that the removal of a few hydrogen bonding groups in the guanidinium ions leads to such a significant change in the activity and structure of the peptide in the membrane. The remaining antimicrobial activity of Argmm-PG-1 is clearly mediated by a different mechanism, which we term in-plane diffusion 53.

Dynamics of β-hairpin antimicrobial peptides in lipid membranes

Biological membranes are highly dynamic entities, with lipid molecules undergoing fast lateral diffusion and uniaxial rotational diffusion. As a result membrane proteins are also dynamic. Small membrane peptides often exhibit whole-body motion 54, 55 while larger membrane proteins usually have significant segmental motions 56, 57. For AMPs, the dynamics is indicative of their oligomeric state and their interaction with the lipids. In particular, the motion of the Arg residues in AMPs is interesting to examine.

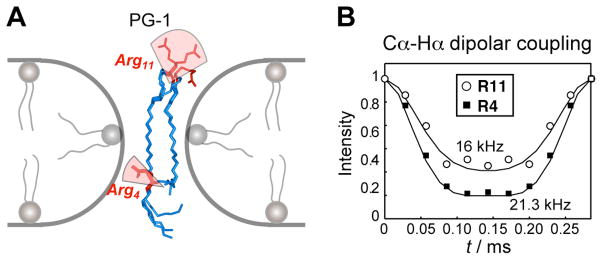

We compared the internal dynamics of two Arg residues in PG-1, one on the β-strand and the other at the β-turn. We measured dipolar couplings, CSAs, and relaxation times of these two residues in POPE/POPG-bound peptide 58. The order parameters obtained from dipolar couplings (Fig. 4B) and CSAs showed that the backbone of Arg4 on the β-strand is rigid, consistent with the highly oligomerized nature of the peptide in this membrane, whereas the backbone of Arg11 at the β-turn is mobile (Fig. 4A). This mobility is understandable because the β-turn is less involved in oligomerization and is close to the mobile water molecules on the membrane surface. Both Arg residues have highly mobile sidechains, but the Arg4 sidechain has larger order parameters, or smaller amplitudes of motion, than Arg11. This is also consistent with the fact that Arg4 in the β-strand is heavily constrained by β-sheet packing.

Fig. 4.

(A) Dynamics of PG-1 arginine residues in the lipid membrane. Arg11 on the β-turn is much more mobile than Arg4 on the β-strand. For simplicity, only two peptides are shown, although PG-1 is oligomerized into larger barrels. (B) Representative C-H dipolar coupling data that revealed the Arg dynamics in PG-1 in lipid membranes 58.

For comparison, the mutant Argmm-PG-1 exhibits whole-body uniaxial rotation in the anionic lipid membrane, as indicated by reduced order parameters for the backbone of strand residues and uniaxial lineshapes of the Cα CSAs 39. This supports a monomeric state of Argmm-PG-1 near the membrane surface. Thus, peptide dynamics clearly reflects the different interactions of PG-1 and Argmm-PG-1 with the lipid bilayer.

Mechanism of antimicrobial activity of PG-1

Based on the above findings about PG-1 depth of insertion, orientation, oligomeric structure, dynamics, and interactions with the lipids, we conclude that a toroidal pore mechanism accounts for PG-1’s antimicrobial activity (Fig. 3B). PG-1 molecules aggregate through intermolecular hydrogen bonds between β-strands and insert into the bilayers to form transmembrane β-barrels that act as pores 29. Due to the strong guanidinium-phosphate interaction, some lipid molecules are dragged by the Arg residues into the center of the bilayer to form torus-shaped defects 30. Because of the oligomerization and the TM orientation, the β-strand is close to the center of the bilayer and mostly rigid, while the β-turn is close to the membrane surface and is highly mobile. In contrast, the hydrogen-bond deficient Argmm-PG-1 resides on the membrane surface and undergoes fast uniaxial rotation around the bilayer normal in a monomeric state 39. Despite the weaker interaction with the lipid headgroups, Argmm-PG-1, through its large-amplitude rotational diffusion in the plane of the membrane, disrupts the cell membrane (Fig. 3E). This in-plane diffusion mechanism also accounts for the activity of TP-I 53.

Future Outlook

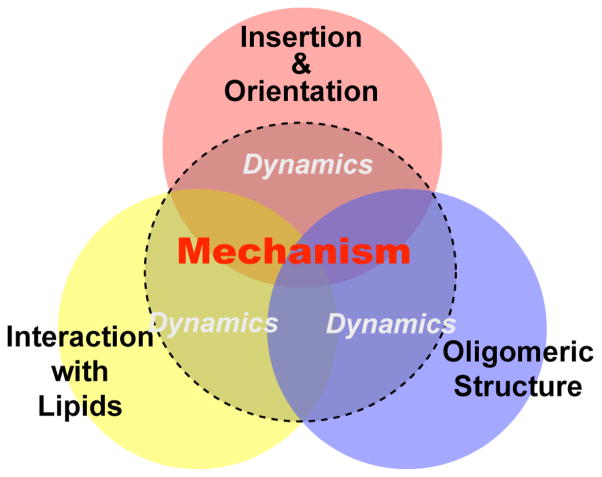

The above review illustrates the rich structural and dynamical information that can be obtained from solid-state NMR studies of antimicrobial peptides and other membrane-active peptides. By examining three major structural aspects: orientation and insertion, lipid interaction, and oligomeric structure, one is well positioned to deduce the mechanism of action of these immune-defense molecules (Fig. 5). Peptide dynamics can affect the spectra of all three aspects and always needs to be examined in detail before the mechanism of action can be concluded.

Fig. 5.

Summary of the main structural aspects of antimicrobial peptides that have been studied using solid-state NMR. Insertion and orientation, interactions with lipids, and oligomeric structure information are combined to deduce the mechanism of action of the peptides. The peptide dynamics reflect all three aspects and is important to examine to validate the mechanism.

Future studies should investigate how general the above mechanism of action of PG-1 is among β-hairpin antimicrobial peptides. Addressing this question will require comparative high-resolution structural studies of other peptides. Work from our laboratories suggest that changes in the distribution of the cationic residues versus hydrophobic residues may readily alter the antimicrobial mechanism, and formation of long-lasting pore is not the only mode of membrane disruption. Other mechanisms include, for example, membrane perturbation caused by highly dynamic peptides that undergo fast rotational diffusion in the membrane plane 39, 53, 55 m and massive aggregation of peptides on the membrane surface 52, 53.

One family of β-sheet-rich antimicrobial peptides that is particularly worthy of SSNMR structural investigation is the human defensins 59. These are larger peptides with more complex three-dimensional folds, as they contain not only β-strand segments but also coils and helices. Clearly, their direct relevance to human innate immune defense makes them important targets for high-resolution structure determination in the bilayer milieu.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by NIH grant GM066976 to M. H.

Biographies

Dr. Ming Tang received his PhD in Chemistry from Professor Mei Hong’s group at Iowa State University in 2008. His research has focused on solid-state NMR investigations of the structure and dynamics of β-hairpin antimicrobial peptides in lipid membranes. He is now a postdoctoral research associate in Professor Chad Rienstra’s group at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His current research interest is the structure of membrane proteins involved in disulfide bond formation.

Dr. Mei Hong, John D. Corbett Professor of Chemistry at Iowa State University, received her B.A. degree from Mount Holyoke College in 1992 and her Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley in 1996. Following one year of research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as an NIH postdoctoral fellow and two years at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst as a research professor, she joined the faculty at Iowa State University in 1999. Her research focuses on the development and application of solid-state NMR techniques to investigate the structure and dynamics of membrane peptides and proteins, fibrous proteins, and complex biopolymers.

References

- 1.Epand RM, Vogel HJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:11–28. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zasloff M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5449–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Odeberg J, Bergman T, Olsson B, Salcedo R. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0325z.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura T, Furunaka H, Miyata T, Tokunaga F, Muta T, Iwanaga S, Niwa M, Takao T, Shimonishi Y. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16709–16713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellm L, Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:1731–1742. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan DI, Prenner EJ, Vogel HJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1184–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouser G, Nelson GJ, Fleischer S, Simon G. In: Biological membranes; physical fact and function. Chapman D, editor. Academic Press; London, New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuzaki K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shai Y. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumann G, Mueller P. J Supramol Struct. 1974;2:538–557. doi: 10.1002/jss.400020504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He K, Ludtke SJ, Worcester DL, Huang HW. Biophys J. 1996;70:2659–2666. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pouny Y, Rapaport D, Mor A, Nicolas P, Shai Y. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12416–12423. doi: 10.1021/bi00164a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludtke SJ, He K, Heller WT, Harroun TA, Yang L, Huang HW. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13723–13728. doi: 10.1021/bi9620621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuzaki K, Murase O, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11361–11368. doi: 10.1021/bi960016v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokryakov VN, Harwig SS, Panyutich EA, Shevchenko AA, Aleshina GM, Shamova OV, Korneva HA, Lehrer RI. FEBS Lett. 1993;327:231–236. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80175-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu XD, Harwig SSL, Oren A, Shafer WM, Lehrer RI. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1240–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1240-1245.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J, Falla TJ, Liu HJ, Hurst MA, Fujii CA, Mosca DA, Embree JR, Loury DJ, Radel PA, Chang CC, Gu L, Fiddes JC. Biopolymers. 2000;55:88–98. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2000)55:1<88::AID-BIP80>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehrer RI, Barton A, Ganz T. J Immunol Methods. 1988;108:153–158. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ternovsky VI, Okada Y, Sabirov RZ. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:433–436. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang L, Weiss TM, Lehrer RI, Huang HW. Biophys J. 2000;79:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luca S, Heise H, Baldus M. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:858–865. doi: 10.1021/ar020232y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong M. Acc Chem Res. 2006;39:176–183. doi: 10.1021/ar040037e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong M. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10340–10351. doi: 10.1021/jp073652j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buffy JJ, Hong T, Yamaguchi S, Waring A, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Biophys J. 2003;85:2363–2373. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y, Mani R, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8856–8864. doi: 10.1021/ja802383t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiener MC, White SH. Biophys J. 1992;61:434–447. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huster D, Yao XL, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:874–883. doi: 10.1021/ja017001r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buffy JJ, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13725–13734. doi: 10.1021/bi035187w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mani R, Cady SD, Tang M, Waring AJ, Lehrert RI, Hong M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16242–16247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605079103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang M, Waring AJ, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11438–11446. doi: 10.1021/ja072511s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Opella SJ, Marassi FM. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3587–3606. doi: 10.1021/cr0304121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Denny J, Tian C, Kim S, Mo Y, Kovacs F, Song Z, Nishimura K, Gan Z, Fu R, Quine JR, Cross TA. J Magn Reson. 2000;144:162–167. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahalakshmi R, Franzin CM, Choi J, Marassi FM. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:3216–3224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marassi FM. Biophys J. 2001;80:994–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang M, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Biophys J. 2006;90:3616–3624. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi S, Hong T, Waring A, Lehrer RI, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9852–9862. doi: 10.1021/bi0257991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong M, Doherty T. Chem Phys Lett. 2006;432:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cady SD, Goodman C, Tatko CD, DeGrado WF, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5719–5729. doi: 10.1021/ja070305e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang M, Waring AJ, Lehrer RL, Hong M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3202–3205. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roumestand C, Louis V, Aumelas A, Grassy G, Calas B, Chavanieu A. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buffy JJ, Waring AJ, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4477–4483. doi: 10.1021/ja043621r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo W, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7242–7251. doi: 10.1021/ja0603406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mani R, Tang M, Wu X, Buffy JJ, Waring AJ, Sherman MA, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8341–8349. doi: 10.1021/bi060305b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang M, Waring AJ, Hong M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13919–13927. doi: 10.1021/ja0526665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White SH, Wimley WC. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wimley WC, White SH. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hessa T, Meindl-Beinker NM, Bernsel A, Kim H, Sato Y, Lerch-Bader M, Nilsson I, White SH, von Heijne G. Nature. 2007;450:1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/nature06387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hessa T, White SH, von Heijne G. Science. 2005;307:1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1109176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freites JA, Tobias DJ, von Heijne G, White SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15059–15064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507618102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herce HD, Garcia AE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20805–20810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schug KA, Lindner W. Chem Rev. 2005;105:67–114. doi: 10.1021/cr040603j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang M, Waring AJ, Hong M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doherty T, Waring AJ, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1105–1116. doi: 10.1021/bi701390t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park SH, Prytulla S, De Angelis AA, Brown JM, Kiefer H, Opella SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7402–7403. doi: 10.1021/ja0606632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamaguchi S, Huster D, Waring A, Lehrer RI, Tack BF, Kearney W, Hong M. Biophys J. 2001;81:2203–2214. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75868-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huster D, Xiao LS, Hong M. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7662–7674. doi: 10.1021/bi0027231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reuther G, Tan KT, Vogel A, Nowak C, Arnold K, Kuhlmann J, Waldmann H, Huster D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13840–13846. doi: 10.1021/ja063635s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang M, Waring AJ, Hong M. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1487–1492. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]