Abstract

Body image, including how a woman views her genitals, has been shown to impact sexuality. Currently, there are no valid and reliable questionnaires to assess body image specific to women with genital changes from pelvic organ prolapse. The purpose of this study was to assess implementation of a body image questionnaire in women with pelvic organ prolapse. The Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale showed utility and potential for demonstrating change in body image after prolapse surgery.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, sexuality, body image, women's sexual health

Introduction

A woman's feelings about her body can have an impact on her quality of life. Body image is more than just how one views her physical body, it encompasses a person's feeling of “wholeness, functionality, and ability to relate to others” (Pelusi, 2006, p.32). Body image, including how a woman views her genitals, has been shown to impact sexuality (Graham, Sanders, Milhausen, & McBride, 2004; Berman, Berman, Miles, Pollets, & Powell, 2003). Feingold & Mazella (1998) studied gender differences and noted women are increasingly dissatisfied with their bodies. Sexuality is a vital part of the human experience. According to Ng and colleagues, “its full development depends upon the satisfaction of basic human needs such as the desire for contact, intimacy, emotional expression, pleasure, tenderness and love” (Ng, Borras-Valls, Perez-Conchillor, & Coleman, 2000, ¶ 1).

The effect of physical changes associated with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) on women's body image and how that influences sexuality has generated very little research. It is hypothesized that physical changes, such as prolapse, would have a negative effect on a woman's perception of her body and potentially impact her sexuality. Currently there are no valid and reliable questionnaires to assess body image specific to women with genital changes from POP. Such a questionnaire would be useful for health care providers caring for women with POP.

Background and Significance

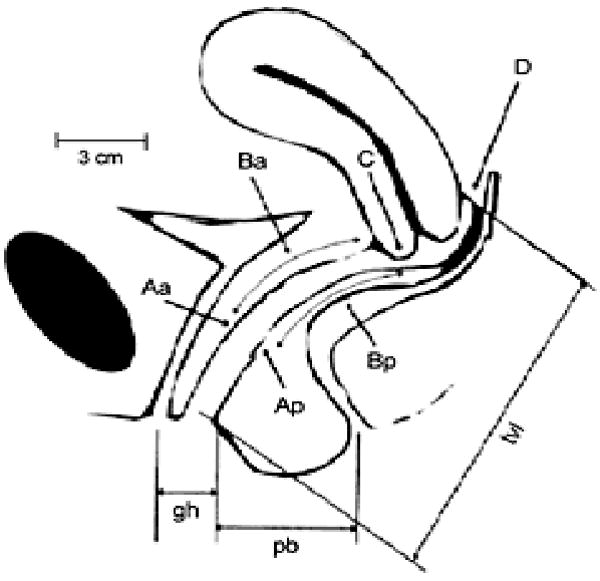

POP is defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007, p. 461) as “descent of one or more pelvic structures.” Classification of prolapse is currently based on the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) as defined by Bump, Mattiasson, Bo, Brubaker, DeLancey, Klaskov, Shull & Smith (1996). Staging by POPQ is detailed in Appendix A.

The exact number of women affected by prolapse is difficult to quantify because symptoms vary widely and some women may be embarrassed to discuss it with their health care providers. Studies of women undergoing routine gynecologic exams found that between 37% and 50% of women had Stage II or III prolapse (Swift, 2000; Swift, Woodman, O'Boyle, Kahn, Valley, Bland, Wang, & Schaffer, 2005). Over 200,000 women in the United States have surgery every year to alleviate the symptoms of POP (Boyles, Weber, & Meyn, 2003). As the population in the United States ages, it is estimated that the number of women seeking treatment for POP will double within the next 30 years (Luber, Boero, & Choe, 2001). Symptoms vary widely, although a feeling of pressure or noticing a bulge at the vaginal introitus is common (Ellerkmann, Cundiff, Melick, Nihira, Leffler, & Bent, 2001; Thakar & Stanton, 2002). Women may experience urinary symptoms such as incontinence, prolonged or intermittent flow, or inability to fully empty the bladder. Bowel symptoms can include constipation or incomplete evacuation (Ellerkmann et al., 2001; Thakar & Stanton, 2002). Severity of symptoms is not strongly correlated with the extent of prolapse and some women experience no symptoms (Ellerkmann et al., 2001).

POP can also affect sexual function. Women with POP may experience lower libido, are less likely to be sexually active, and more likely to have vaginal dryness compared to their counterparts without prolapse (Handa, Cundiff, Chang, & Helzour, 2008). Prolapse can make intercourse uncomfortable or impossible because of the bulging into the vagina (Ellerkmann et al., 2001). The incontinence of urine or stool that can occur during intercourse may also impact both frequency and enjoyment of sexual activity (Rogers, Kammerer-Doak, Villarreal, Coates, & Qualls, 2001).

Research regarding sexual function before and after POP surgery has been inconclusive. Some studies have shown an improvement (Rogers, Kammerer-Doak, Darrow, Murray, Qualls, Olsen & Barber, 2006) while others have shown a worsening in sexual function following surgery (Black, Bowling, Griffiths, Pope, & Abel, 1998). Pain with intercourse can be a complication following prolapse surgery regardless of type of procedure (Weber, Walters, & Piedmonte, 2000). Frequently there is an improvement in incontinence during intercourse (Weber et al., 2000) although use of graft materials may increase the risk (Novi, Bradley, Mahmoud, Morgan, & Arya, 2007). Studies have consistently shown that ability to orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and libido are not improved following surgery for prolapse (Mazouni, Karsenti, Bretelle, Bladou, Gamerre, & Serment, 2004; Weber et al., 2000)

Research pertinent to sexuality and POP has most often been measured in terms of sexual function i.e. frequency, desire, or pain (Rogers et al., 2001). Only recently has attention been given to body image changes associated with POP. In a case control study published after the data collection process of this study, Jelovsek and Barber (2006) found that women with Stage III or IV prolapse were more likely to feel self-conscious and less likely to feel feminine and sexually attractive than their counterparts without pelvic organ prolapse. Despite the fact that POP is ultimately a condition that affects quality of life, its impact on women's body image and sexuality is understudied.

Purpose of the Study

This study was embedded within a larger qualitative study designed to better understand women's experiences of living with POP. A body image questionnaire, Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale (VSBE) was implemented along with a semi structured interview process. The two research questions posed in this study were:

Research Question 1- Does the VSBE scale show utility for use in assessing body image and sexual health in women with POP?

Research Question 2- How do women with POP who have low VSBE scores (indicating more body image dissatisfaction) qualitatively describe their experience of living with POP and its effect on their body image and sexual health?

Although the main method of data collection was through a semi-structured interview process (see Appendix B), at the end of the interviews women were asked to respond to a 10 item survey – the Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale (VSBE, see Appendix C). This paper presents the results of the final portion of the interview using the VSBE scale while also situating the results in the fuller context of the interview provided by each individual woman.

Materials and Methods

Participants were recruited from a pool of 62 women (with Stage II prolapse or greater) who had participated in a previous study of POP mechanisms and treatment. This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Because the initial research had begun six years prior, some original participants were no longer available for follow up. Of the 28 women contacted, 13 agreed to be interviewed. Inclusion criteria for our study included; prolapse of Stage II or greater (which was documented in the parent study) and willingness to participate in a recorded telephone interview. Telephone interviews were chosen for participant convenience as this method has been shown to be effective when eliciting information regarding sensitive topics (Ellen, Gurvey, Pasch, Tschann, Nanda, & Catania, 2002).

Data were collected during the telephone interviews where participants responded to questions regarding their experience of prolapse. A semi-structured interview guide was used that had been developed by expert clinicians who identified key areas of concern expressed by women with pelvic organ prolapse in the medical clinic setting (see Appendix B). This guide was not subjected to quantitative reliability and validity testing. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim by the primary interviewer and analyzed by members of the research team. Results from the primary qualitative data will be reported independently from the results reported here. For the secondary, analysis at the end of the interviews, women were asked to give their responses to the ten question (VSBE) scale. The VSBE was developed and piloted by one of the authors (Miller, J. - unpublished) to assess women's body image and sexuality following childbirth. This initial work adapted a body image and sexuality questionnaire originally developed for use with people experiencing disabilities (Taleperos & McCabe, 2002). The Physical Disability Sexuality and Body Esteem Scale was subject to tests of validity and reliability and had high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, as well as construct and divergent validity (Taleperos & McCabe, 2002). Permission to use the scale was obtained from the authors. The questions were modified to reflect genital body image and the questionnaire was renamed the “Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale” (VSBE). The VSBE was chosen for our investigation because childbirth and POP both affect the female genital area.

The VSBE consists of ten questions with Likert scale responses ranging from 1 – (“strongly agree”) to 5 – (“strongly disagree”). The VSBE used for this study has been included as Appendix C, with a slightly revised version as Appendix D. Scores ranged from 10 to 50, with lower scores indicating more negative genital body image. The prior research using the VSBE has not been published.

By asking the participants for verbal responses rather than written, their acceptance as well as their understanding of the questions could be better assessed. For example, questions could be clarified or a participant could verbally indicate that a question was not pertinent. Women who had undergone surgery for prolapse, since the initial assessment from the previous study, were asked to give two responses to each question. The first response was to recall genital body image before surgery and the second response reflecting current genital body image.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis of the VSBE scores was done to assess for missing data, mean and range of scores. A variation of conventional content analysis methods (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) was then done where each transcript was read in its entirety by a member of the research team with particular attention to the participants who scored particularly low on the VSBE; the focus being interview content regarding sexual health and body image. The key area of focus in the review of the transcripts was on the interview questions “Do you view your body any differently since you've come to know that you have prolapse?” and “Have you had any sexual issues with the prolapse?” The participant's responses that were pertinent to body image and sexuality were then compared with individual scores on the VSBE. These individual responses were also compared to see if there were commonalities in women's experiences with body image and sexual health.

Based on comments from their interviews, women were classified as either sexually active or not sexually active. Their scores on the VSBE were then compared to determine if responses differed. Due to the sample size, this was accomplished using the non-parametric Mann Whitney U statistical test. Correlation between severity of prolapse and VSBE scores were calculated using the non-parametric Spearman Rank Order Correlation.

Results

Thirteen women with known POP completed the study. The mean age of the women was 57.3 years, ranging from 33 to 81 years. All women were Caucasian and were in the middle to upper income bracket. Severity of prolapse ranged from Stage II to Stage IV and is shown in Table 1 in relationship to participants' age.

Table 1. Participant's Age and Stage of Prolapse.

| Participant Age | Stage of Prolapse |

|---|---|

| 33 | II |

| 39 | III |

| 39 | III |

| 39 | III |

| 53 | III |

| 61 | III |

| 62 | III |

| 64 | III |

| 65 | II |

| 69 | III |

| 69 | III |

| 71 | III |

| 81 | IV |

Quantitative Results

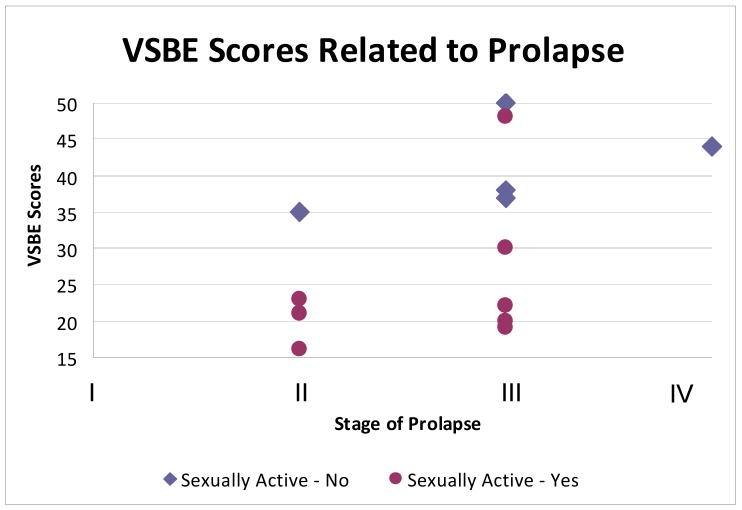

Mean score on the VSBE was 31.1 (SD = 9.0) out of a possible score of 50, with higher numbers indicating more positive genital body image. Of the thirteen women interviewed, eight were classified as sexually active. These women had a mean VSBE score of 25.1 (SD = 10.8), while women classified as not sexually active (n = 5) had a mean score of 40.8 (SD = 6.1). This suggests that in our study, women with POP classified as sexually active scored significantly lower (p = .023) on the VSBE than women who were not sexually active.

The three participants who had undergone surgery for their prolapse showed improved VSBE scores in the present compared to the scores which reflected back to their body image pre-surgery. Mean improvement in VSBE was 15 points. Statistical analysis was not conducted due to the small sample size.

There was a positive correlation between severity of prolapse and VSBE scores (r = .592 p = .033) meaning that the worse the prolapse the better the body image (see Figure 1). Although this seems counterintuitive, it may have been because severity of prolapse tends to increase with age. In fact this correlation was very similar to the correlation found in this study between age and degree of prolapse (r =.593 p = .033). Also, women in our study who were older were less likely to be classified as sexually active (p =.04).

Figure 1. Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem (VSBE) Scale Scores as They Relate to Stage of Prolapse and Sexuality.

Qualitative Results

Every participant answered all ten questions on the VSBE. Three of the women (who from their comments implied that they were not sexually active) expressed discomfort with the content of the questions; “I'm not married, don't plan on getting married, and as far as having sex, I wouldn't do that without being married” (age 69, VSBE score = 50); and “I'm not looking for a sexual partner” (age 69, VSBE score = 37). One woman felt that some questions were not pertinent because she was not looking for a new partner “this is all sort of mythical because I'm married and I have a very happy marriage” (Age 71, VSBE score = 30).

Five of the eight women who were sexually active indicated that the prolapse had impacted their body image and sexuality in a negative way. These five women also had the lowest VSBE scores, ranging from 16 to 24.

From the interview transcripts, participant comments that were pertinent to body image and sexual health were identified. These comments were then compared to allow commonalities to emerge. Any theme that was common to at least two participants has been included in the results presented below.

Incontinence and Sexuality

Two women reported that incontinence affected their body image and sexuality. One of the women commented, “It's also impacted my sexual life…the incontinence has even occurred during sex. So that's been a definite turn off. I think it has affected me in terms of viewing myself in terms of less desirable because of this potentially happening” (Age 53, VSBE score = 21).

Prolapse and Discomfort with Intercourse

Three women indicated that there was discomfort with intercourse. One commented, “It's not a comfortable thing. You want to; even sexually you couldn't be in a top position because you felt like you were coming out. It just was very uncomfortable” (Age 39, VSBE score = 20). Certain positions were more uncomfortable for these women and one remarked, “One of the painful side effects…is that sexual intercourse is at times intolerable. There are positions that before were favored are no longer even possible” (Age 33, VSBE score = 23).

Partner's Response to Prolapse

Four of the women expressed concerns about their partner's sexual needs or satisfaction. One woman stated, “I think he was frustrated. He was looking for better relations sexually” (Age 39, VSBE score = 20). Another woman said, “He's kind of squeamish with some things that happen…He's afraid of hurting me…He has a hard time inserting his penis” (Age 65, VSBE score = 16). One woman expressed anxiety about how her husband viewed her sexually: “I'm embarrassed about this, I was so afraid I was sexually unattractive to my husband. That was a big fear of mine” (Age 39, VSBE score = 19). And one woman who was not sexually active expressed her thoughts regarding sexuality with pelvic organ prolapse: “My husband and I aren't intimate…but if we were, it would create/cause a problem” (Age 64, VSBE score = 38).

Prolapse and feelings of femininity

POP appeared to change how two women felt about their femininity. One woman noted, “It hit the feminine part of me, I was very young, still sexually active, I was afraid that it would interfere with, in the fact that it just, it just made me feel…less feminine” (Age 33, VSBE score 23).

Discussion

Previous research regarding sexuality in women experiencing POP has mainly focused on sexual function (frequency, pain, and orgasm). This study was an attempt to address a gap in our understanding regarding how women with POP view their bodies and how this may influence their sexuality. The VSBE performed as expected in women with prolapse who we classified as sexually active. Additionally, the questionnaire was acceptable for use by the women in this study. Despite the sensitive nature of genital body image and sexuality, all women in the study answered the questions. By obtaining responses to the VSBE verbally rather than by pen and paper we were able to elicit comments regarding the questionnaire. Four women who were sexually active commented on question # 2 of the VSBE (i.e. I am not looking for a partner) so the question was changed to read “if I were looking for a partner.” The other revisions are minor changes to sentence structure to aid in participant understanding. The revised version is included as Appendix D.

The groundbreaking research of Jelovsek and Barber (2006) showed that pelvic organ prolapse impacts body image and that addressing body image is an important part of clinical assessment. Our findings concur with theirs; body image is an important issue for women with prolapse. Results of this study also shed some understanding of how body image may impact sexuality in women with pelvic organ prolapse. The preliminary data also suggests that body image may improve after surgery for prolapse.

This study has relevance for both clinicians and researchers. Although the VSBE has yet to be extensively evaluated for reliability and validity, it shows promise for researchers and clinicians wanting to assess body image and sexuality, particularly with women who are sexually active. This questionnaire is a quick and easy way to assess concerns regarding how treatment/surgery may impact body image and sexuality. Of particular interest is whether body image scores improve after surgery. This area needs further exploration to validate our preliminary findings that showed improvement in body image scores after surgery. Improvement in sexuality following surgery may, in part, be a result of improved body image as well as an improvement in sexual function. Our research in the area of genital body image and sexual health in women with POP is ongoing.

Limitations

This study was limited by the small size and homogeneity of the sample (Caucasian, middle to upper income) affecting its generalizability to other populations. None of our study participants were single and interested in dating/finding a sexual partner; a group of women who may be particularly impacted by the effect of POP on body image and sexuality. The responses pertaining to body image and sexuality prior to surgery relied on participant recall; a potential limitation. The study was also limited by the lack of specific questions related to sexual activities leading to the need to classify women as sexually active or not based on inference from their interview comments.

Conclusion

Use of the VSBE scale may have potential in both the research and clinical arena. For researchers, the VSBE could be used as an adjunct to existing valid and reliable questionnaires as a way to address the potential impact of POP on women's body image. Clinicians could use the VSBE as a screening tool to identify women who may experience alterations in body image associated with their POP. Using the VSBE as adjunct to the clinical interview, the health care provider may be better able to identify possible areas of concern women have regarding their health status. Thus, a more tailored approach to addressing the woman's individual needs can be developed.

As the population of aging women grows, increasing numbers of women will be affected by POP. It is important that as researchers and clinicians we understand how this can affect women, not only physically, but also how they view their bodies and how that may influence sexuality and decisions about care, including surgery. By assessing and acknowledging the issues of body image and sexuality we can better understand and care for women experiencing POP.

Acknowledgments

Julie Sarkesian (Diepehl) for her initial conceptualization of the VSBE and its application to childbearing women in an undergraduate honors student project directed by Janis Miller.

Funding: The parent study for this work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) RO1 HD 038665 and investigator support was provided from The Office for Research on Women's Health's SCOR on Sex and Gender Factors Affecting Women's Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through grants P50 HD044406.

Appendix A

Stages of Pelvic Organ Prolapse.

| Stages are based on the maximal extent of prolapse relative to the hymen: | |

| Stage 0: | No prolapse; anterior and posterior points are all – 3 cm. |

| Stage I: | The criteria for stage 0 are not met, and the most distal prolapse is more than 1 cm above the level of the hymen |

| Stage II: | The most distal prolapse is between 1 cm above and 1 cm below the hymen |

| Stage III: | The most distal prolapse is more than 1cm below the hymen but no further than 2 cm less than TVL |

| Stage IV: | Represents complete vault eversion |

| |

| Six vaginal sites used in staging prolapse: | |

| Points Aa and Ba anteriorly | |

| Points Ap and Bp posteriorly | |

| Point C for the cervix or vaginal apex | |

| Point D for the posterior fornix (not measured after hysterectomy) | |

| GH – genital hiatus | |

| PB – perineal body | |

| TVL – total vaginal length | |

Appendix B

Semi-structured questions

How would you describe prolapse?

Tell me about when you first noticed the prolapse: when did you first notice it, what did it feel like, and what did you think it was?

In your opinion why do you think this happened?

How did you feel once you noticed it (physically, mentally, emotionally)?

Did you talk with anyone about this? If so, who? If no, why not?

If you did talk to someone, did they suggest any treatment or explain why this was happening?

Did you seek treatment? Why/why not?

How long after you noticed did you seek treatment? Why [THAT AMOUNT OF TIME] (example: 2 weeks, 3 months, 5 years, etc.)?

Tell me about what types of expectations you had when you sought treatment.

Who did you go to for treatment? Why?

Tell me about the kinds of information you were given and what kind of information you wish you had been given.

How did you first come to understand that you had prolapse and get information about it?

How do you view your body in relationship to prolapse. Has the way you think about your body changed at all? Can you explain….

After you knew what was happening to you did you discuss this with anyone else? Why did or didn't you talk about with them?

Have you ever had a negative experience when you have talked about prolapse with other people.

Have you ever had a positive experience when you talked with someone about prolapse?

Did/Does POP impact any part of your career or social life?

Where did/does pelvic organ prolapse fit into the hierarchy of needs such as children, work life, etc.?

After experiencing prolapse yourself, how do you view other women with prolapse?

Why do you think women do or do not discuss prolapse with others?

Is there anything else that we didn't touch on that you think we should have?

-

How many children have you had?

What is their birth order and weight of each?

Were there any interventions for any of them?

How many total hours were you in labor and how long was the second stage?

-

Do you feel that there is a link between birth and prolapse? (if yes ask the following)

What, in particular, do believe is link between the two?

How long after delivery did you first notice the prolapse?

-

If you had to do your births all over again would you change anything?

Why or why not?

What would you tell a young woman about to give birth for the first time concerning prolapse?

Do you feel one of your births in particular had more of a connection to prolapse than another?

-

Did you have surgery for your prolapse? Why or why not? (If yes ask following)

What did you expect from surgery?

Was the outcome what you expected?

Were you needs fully met?

Was the outcome what your doctor expected?

What more would you have liked done that wasn't?

How did you view your body before the surgery and how do you view your body now, after the surgery?

Was your husband or sexual partner involved in any of the discussion/decision?

Knowing what you know now, what would you want communicated to other women about this condition?

How do you think the provider could improve in order to meet the needs of women with prolapse?

How do you think the health care system can improve itself to meet the needs of women with prolapse?

Any other questions you think we should have asked but didn't?

Appendix C

Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale (ORIGINAL FORM).

Items are scored 1 – strongly agree to 5 – strongly disagree

|

Adapted from Taleperos & McCabe, 2002.

Appendix D

Vaginal Changes Sexual and Body Esteem Scale (REVISED VERSION).

Items are scored 1 – strongly agree to 5 – strongly disagree

|

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin - pelvic organ prolapse. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;109(2 Part 1):461–473. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200702000-00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman L, Berman J, Miles M, Pollets D, Powell J. Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: Relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2003;29(s):11–21. doi: 10.1080/713847124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S, Bowling A, Griffiths J, Pope C, Abel P. Impact of surgery for stress incontinence on the social lives of women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;105:605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyles S, Weber A, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:108–115. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bump R, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker L, DeLancey J, Klaskov P, Shull B, Smith A. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1996;175:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen J, Gurvey J, Pasch L, Tschann J, Nanda J, Catania J. A randomized comparison of A-CASI and phone interviews to assess STD/HIV-related risk behaviors in teens. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(1):26–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerkmann R, Cundiff G, Melick C, Nihira M, Leffler K, Bent A. Correlation of symptoms with location and severity of pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185(6):1332–1338. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.119078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Mazzella R. Gender differences in body image are increasing. Psychological Science. 1998;9(3):190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Graham C, Sanders S, Milhausen R, McBride K. Turning on and turning off: A focus group study of the factors that affect women's sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(6):527–538. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044737.62561.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa V, Cundiff G, Chang H, Helzlsouer K. Female sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;111(5):1045. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816bbe85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelovsek J, Barber M. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;194(5):1455–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber K, Boero S, Choe J. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: Current observations and future projections. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184:1496–1503. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazouni C, Karsenty G, Bretelle F, Bladou F, Gamerre M, Serment G. Urinary complications and sexual function after the tension free vaginal tape procedure. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2004;83:955–961. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novi J, Bradley C, Mahmoud N, Morgan M, Arya L. Sexual function in women after rectocele repair with acellular porcine dermis graft vs. site-specific rectovaginal fascia repair. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2007;18(10):1163. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng E, Borras-Valls, Perez-Conchillo M, Coleman E, editors. Sexuality in the New Millennium. 2000 Bologna, Editrice Compositor: also on the World Association of Sexology website < www.tc.umn.edu/∼coleman001/was/wdecla/htm.

- Pelusi J. Sexuality and body image. American Journal of Nursing. 2006;106(3(S)):32–38. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200603003-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R, Kammerer-Doak D, Villarreal A, Coates K, Qualls C. A new instrument to measure sexual function in women with urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184(4):552–558. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R, Kammerer-Doak D, Darrow A, Murray K, Qualls C, Olsen A, Barber M. Does sexual function change after surgery for stress urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse? A multicenter prospective study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195(5):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift S. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183(2):277–285. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift S, Woodman P, O'Boyle A, Kahn M, Valley M, Bland D, Wang W, Schaffer J. Pelvic organ support study (POSST): The distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(3):795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taleperos G, McCabe M. Development and validation of the physical disability sexual and body esteem scale. Sexuality and Disability. 2002;20(3):159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Thakar R, Stanton S. Management of genital prolapse. British Medical Journal. 2002;324:1258–1262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7348.1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Walters M, Piedmonte M. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;182(6):1610–1615. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]