Abstract

BACKGROUND:

It is postulated that children with asthma who receive an interactive, comprehensive education program would improve their quality of life, asthma management and asthma control compared with children receiving usual care.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the feasibility and impact of ‘Roaring Adventures of Puff’ (RAP), a six-week childhood asthma education program administered by health professionals in schools.

METHODS:

Thirty-four schools from three health regions in Alberta were randomly assigned to receive either the RAP asthma program (intervention group) or usual care (control group). Baseline measurements from parent and child were taken before the intervention, and at six and 12 months.

RESULTS:

The intervention group had more smoke exposure at baseline. Participants lost to follow-up had more asthma symptoms. Improvements were significantly greater in the RAP intervention group from baseline to six months than in the control group in terms of parent’s perceived understanding and ability to cope with and control asthma, and overall quality of life (P<0.05). On follow-up, doctor visits were reduced in the control group.

CONCLUSION:

A multilevel, comprehensive, school-based asthma program is feasible, and modestly improved asthma management and quality of life outcomes. An interactive group education program offered to children with asthma at their school has merit as a practical, cost-effective, peer-supportive approach to improve health outcomes.

Keywords: Asthma education, Childhood asthma, Program evaluation, Quality of life, School-based program

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

On postule que les enfants asthmatiques qui reçoivent un programme d’éducation interactif complet améliorent leur qualité de vie ainsi que leur prise en charge et leur contrôle de l’asthme par rapport aux enfants qui reçoivent des soins habituels.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer la faisabilité et les répercussions du programme Roaring Adventures of Puff (RAP), un programme d’éducation sur l’asthme de six semaines pour les enfants, administré par des professionnels de la santé dans les écoles.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Trente-quatre écoles de trois régions sanitaires de l’Alberta ont été réparties aléatoirement entre le programme RAP (groupe d’intervention) et les soins habituels (groupe témoin). Les chercheurs ont obtenu les mesures auprès des parents et des enfants avant l’intervention, puis au bout de six et de 12 mois.

RÉSULTATS :

Le groupe d’intervention était davantage exposé à la fumée du tabac en début d’étude. Les participants perdus au suivi avaient plus de symptômes d’asthme. L’amélioration était considérablement plus marquée dans le groupe d’intervention RAP entre le début et six mois que dans le groupe témoin pour ce qui est de la compréhension perçue des parents, de la capacité d’affronter et de contrôler l’asthme et de la qualité de vie globale (P<0,05). Au suivi, les visites au médecin étaient réduites dans le groupe témoin.

CONCLUSION :

Il est faisable d’offrir un programme d’éducation sur l’asthme en milieu scolaire complet et multiniveau, et ce programme améliore modestement la prise en charge de l’asthme et les résultats sur la qualité de vie. Un programme d’éducation collectif interactif offert à des enfants asthmatiques en milieu scolaire a l’avantage d’être une démarche pratique, rentable et soutenue par les camarades pour améliorer les issues de santé.

Asthma affects a child’s quality of life (1) and overall health (2,3). Although children with asthma should be able to achieve good asthma control (4), asthma is poorly controlled in this population (2,3,5), likely due to a multitude of complex and continuously evolving factors (6,7). Some of these factors include a lack of care continuity (8), inadequate use of clinical practice guidelines (9,10), poor patient compliance (11), patient characteristics (12–14) and physician characteristics (13,15). Novel approaches are needed to address the complex problem of achieving optimal asthma management and control.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of childhood asthma education programs suggest that recent approaches guided by evidence-based strategies and a cognitively appropriate theoretical framework are most effective (16–18). Furthermore, attitudes, knowledge and skills of the care givers significantly affect the child’s ability to develop and use management behaviours and access appropriate care (19,20). Consideration of the child’s environment, both social and physical at school and at home, influence the child’s asthma control and quality of life (QOL) (19,21). School-based asthma management programs are easily accessible to children with asthma, their peers and caregivers, and are known to be feasible strategies (22,23). The ‘Roaring Adventures of Puff’ (RAP) is a child-centred, school-based, asthma education program (24). RAP incorporates a multitude of childhood educational approaches based on theory and evidence of factors that influence a child’s motivation, efficacy, management and QOL. Previously, a feasibility study of RAP was conducted using student instructors supervised by the school’s community health nurse (25). Children in the RAP intervention schools had statistically significant improvements in unscheduled doctor visits, missed school days, limitations in the nature of play and correct use of medications. The study showed that a school-based asthma program is feasible. We hypothesized that school-age children with asthma who participated in RAP exhibit improved asthma self-management behaviours and a better QOL, reduced symptoms and improved health care use than children who received the usual asthma care.

METHODS

Population

The study was approved by the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board (Edmonton, Alberta). From a listing of all public schools in participating health regions (Capital Health, Westview and Northwest), 34 schools were randomly selected and agreed to participate in the study (a response rate of 79%). A school health survey was sent home through a school-wide mailing (n=3986; response rate 55%). Parents who reported that their child had physician-diagnosed asthma were identified; interested families were contacted by telephone. Consent was obtained from each parent and child before enrollment in the study. Study inclusion criteria were children attending grades 2 to 5, with a parent-reported diagnosis of asthma by a physician, informed consent from the parent or guardian, ability to speak English and no previous participation in RAP.

Study design

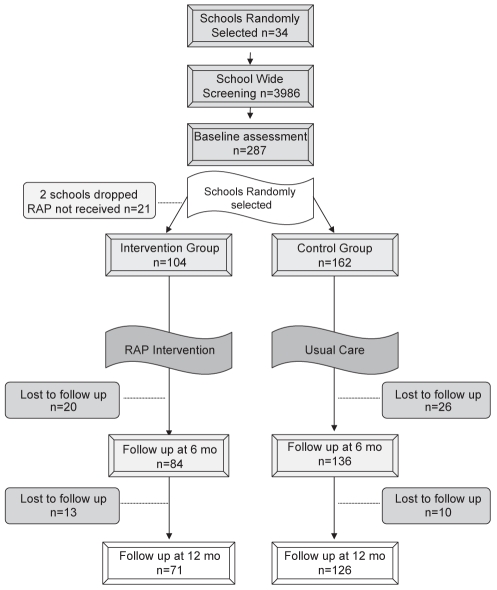

Of the families who agreed to participate, baseline information from each child was gathered at their school using the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) (1). Peak flow measurements were taken for each child at their school. One parent was asked to complete the mailed Parent RAP Questionnaire. The same parent was also asked to complete the PAQLQ from their child’s perspective, without help from their child. Schools were randomly assigned to either the RAP educational intervention or usual care (control group) using a random number table. Both RAP and control groups completed the same questionnaires at six and 12 months after the intervention (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Flow chart of the study timeline, the enrollment process, and subject participation and dropout at three time points. mo Months; RAP Roaring Adventures of Puff

Intervention

Before the RAP intervention, parents and teachers in the intervention schools were invited to participate in a RAP parent/teacher asthma awareness event held at the school (approximately 2 h in an evening). The event provided information on asthma management, school asthma issues and RAP. Group discussions explored how to best support children with asthma and their perceived needs, including environmental control measures, a written asthma action plan for parents and asthma information for the school staff. A session on guidelines for asthma management at school and related resources were offered to school staff. Physicians of the participating children were faxed letters informing them about the study, about RAP and the Canadian asthma consensus guidelines (4). They were also invited to communicate with the RAP educator about their patients and were asked to ensure that the children had written action plans. The RAP instructor consulted the physicians when concerns regarding their patient arose that needed medical consultation.

The health region with jurisdiction over participating schools identified qualified staff to be trained as instructors. Four registered respiratory therapists working in community rehabilitation and one community health nurse attended a two-day workshop on childhood asthma and the teaching of RAP. The RAP instructors’ workshop included asthma information, scenarios, simulations and a written examination. The RAP instructors taught six 45 min to 60 min sessions on a series of asthma topics, including getting to know each other, goal setting, use of a peak flow meter (optional) and diary monitoring; trigger identification, control and avoidance, and basic pathophysiology; purpose of medications and proper use of inhalers; symptom recognition, self-monitoring and the use of an action plan; lifestyle, exercise, fears and managing an asthma episode; and sharing information with teachers and parents (26).

RAP assumes that an individual’s behaviour is determined by a complex interaction among environmental, personal (physiological and cognitive) and behavioural factors. To influence these factors in children with asthma, RAP integrated the following principles of the social cognitive theory (27): self-regulation, observational learning, reinforcement, environmental influences and perceived self-efficacy. The theoretical framework underlying RAP has been discussed in detail previously (24). Teaching strategies included puppetry, games, role play, model building, group interaction, team building, and asthma symptom and management tracking.

Outcome measures

The PAQLQ measures health-related QOL in children with asthma through 23 questions across three domains (symptoms, activity limitations and emotional function). The questionnaire has good measurement properties and has been shown to be reliable and responsive for children seven to 17 years of age (1). The PAQLQ is scored on a scale between 1 and 7, with a clinically significant difference being 0.5 or more. This questionnaire was administered to both the child and their parent. The parent was instructed to answer the questions from their child’s perspective without assistance from the child.

The Parent RAP Questionnaire assessed demographic information, medication use, health care use, school absenteeism, attitudes toward asthma and global asthma ratings of change. The questionnaire was used in our initial feasibility study (25), and was modified to increase face validity and interpretability.

Data analysis

The primary analysis compared pre- and postintervention outcomes for children with asthma receiving RAP, and those not receiving RAP. The comparability of the intervention and control groups at baseline was tested using the Pearson χ2 test. Similar analyses were performed to assess the comparability of those who dropped out and those who continued in the study. Pre- and postintervention changes in categorical outcome variables were assessed using McNemar’s test. Ordinal variables were assessed using the Wilcoxon’s rank test. The number of children who improved or worsened was assigned based on the degree of change calculated from pre- minus postintervention values at both six and 12 months. Using the Pearson χ2 test, differences in the number of children who improved or worsened were compared between the intervention and control groups. A univariate ANOVA was performed on the ordinal variables (using pre- minus postintervention ratings) that showed significant difference from the t test, clustering the intervention and control group, and the smoking and nonsmoking subjects.

RESULTS

Demographics

From 34 schools at baseline, 104 children (not including those who enrolled but did not receive the intervention [n=21]) were assigned to the intervention group and 162 to the control group. The mean age was 8.6 years and diagnosis of asthma occured at a mean age of 3.6 years. Most of the predominantly Caucasian participants lived in the greater Edmonton area, and the small cities of Hinton, Edson, Stony Plain, Spruce Grove and Peace River, Alberta. More than one-half of the participants were male (RAP 55.6%, control 66.7%). More than one-third had other medical problems (RAP 32.4%, control 41.8%) and one-fifth had a cat in the home (RAP 20.4%, control 17.9%). The majority of participants had received some form of asthma education in the past (RAP 53.4%, control 62.3%).

Baseline characteristics

Two differences were found between the groups at baseline (Table 1). The RAP group experienced significantly more smoke in the home than the control group (RAP 41.7%, control 23%; P<0.05). In addition, at baseline, the percentage of parents stating that their ‘ability to control their child’s asthma improved over the past year’ was greater in the control group (RAP 36.2%, control 51.6%; P<0.05). More than two-thirds of parents stated that their child’s asthma rarely interferes with lifestyle (RAP 73.8%, control 64%). Yet, approximately one-half of the parents stated that their child was limited in the nature (RAP 48.5%, control 36.6%) and amount (RAP 55.3%, control 55.9%) of play.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of intervention and control (includes dropouts) groups

|

Group |

||

|---|---|---|

| Intervention, % (n=104) | Control, % (n=162) | |

| Demographic | ||

| Age range, years | ||

| 6–7 | 21.2 | 27.8 |

| 8–10 | 73.1 | 66.7 |

| 11–13 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Male sex | 55.8 | 66.7 |

| Live in town or city | 90.3 | 85.2 |

| Other medical problems | 32.4 | 41.8 |

| Seasonal asthma | 86.1 | 80.2 |

| Ever had an allergic reaction | 63.5 | 72.2 |

| Life-threatening allergic reaction | 22.2 | 24.3 |

| Past asthma education | 53.4 | 62.3 |

| Education >2 years previously | 29.2 | 32.7 |

| Limitation of activity | ||

| Impact of asthma | ||

| Never | 6.8 | 11.2 |

| Rarely | 73.8 | 64.0 |

| Frequently | 18.4 | 23.6 |

| Seriously | 1.0 | 1.2 |

| Missed school days in past year | 67.0 | 54.2 |

| Limited in nature of play | 48.5 | 36.6 |

| Limited in amount of play | 55.3 | 55.9 |

| Level of control/severity | ||

| Unscheduled doctor visit in the past year | 56.3 | 57.5 |

| ED visits in past year | 18.4 | 18.5 |

| Ever in intensive care unit | 7.9 | 5.0 |

| Use of medication | ||

| Used inhaled short-acting bronchodilators in past 2 weeks | 39.4 | 38.9 |

| Used inhaled steroids in past 2 weeks | 34.6 | 35.8 |

| Used inhaled steroids only when sick | 57.8 | 71.7 |

| Used short course of oral steroids in past year | 20.7 | 18.6 |

| Uses correct medication for quick relief | 65.3 | 58.4 |

| Uses correct medication to prevent symptoms | 25.7 | 19.9 |

| Experienced side effects | 42.3 | 35.4 |

| Environment | ||

| Any smoke in home* | 41.7 | 23.0 |

| Cat(s) in the home | 20.4 | 17.9 |

| Animals in the home | 41.7 | 30.9 |

| Management behaviour | ||

| Have written action plan | 26.0 | 23.0 |

| Use peak flow meter | 31.7 | 37.0 |

| Avoid triggers | 28.9 | 37.1 |

| Carry epinephrine | 14.1 | 12.3 |

P<0.05. ED Emergency department

Individuals lost to follow-up

The attrition rate was approximately one-quarter (27%) and did not significantly differ between the two groups (RAP 32%, n=33; control 22%, n=36; P>0.05) (Figure 1). Two intervention schools (not included in any analysis) did not receive the intervention within the study time and were dropped from analysis (n=26). None of the children in the educational intervention dropped out once it commenced. At the six- and 12-month follow-up, most of the individuals lost to follow-up were no longer attending the study school or were not able to be contacted (58%). The remaining individuals chose to discontinue or not complete the questionnaire for various reasons (eg, parent believed the child no longer had asthma or was not interested). Those who were lost to follow-up were significantly older than the participants who remained in the study and appeared to have significantly worse asthma (Table 2), including a higher overall symptom score, more frequently affected by asthma and more limitation in the nature of play. Dropouts also appeared to have poorer asthma management behaviour, including correct use of preventive medication and avoidance of triggers. Their environmental exposures also appear to be significantly worse, including smoke and cats in the home.

TABLE 2.

Demographics, level of control, medication, environment and management for participants and dropouts

| Characteristics | Participants (n=197) | Dropouts (n=69) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age, years (mean) | 8.5 | 8.9* |

| Male sex | 64.0 | 58.0 |

| Other medical problems | 40.1 | 29.4 |

| Any past asthma education | 59.7 | 56.5 |

| Level of control/severity | ||

| Impact of asthma | ||

| Never | 8.2 | 13.2* |

| Rarely | 73.0 | 52.9 |

| Frequently | 17.3 | 33.8 |

| Seriously | 1.5 | 0.0 |

| Missed schools days in the past year, mean | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Limited in nature of play | 35.9 | 56.5* |

| Limited in amount of play | 52.8 | 63.8 |

| Mean asthma symptom score | 6.8 | 8.0* |

| Unscheduled doctor visit in the past year | 58.5 | 52.9 |

| Unscheduled doctor visits, mean | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Emergency department visits in the past year, mean | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Cough in past 2 weeks | ||

| None | 40.0 | 25.0 |

| Mild to moderate | 49.7 | 60.3 |

| Marked to severe | 10.3 | 4.7* |

| Wheeze in past 2 weeks | ||

| None | 60.0 | 52.9 |

| Mild to moderate | 35.4 | 39.7 |

| Marked to severe | 4.9 | 7.4 |

| Shortness of breath in past 2 weeks | ||

| None | 57.4 | 41.2 |

| Mild to moderate | 37.4 | 51.5 |

| Marked to severe | 5.1 | 7.4* |

| Use of medication, environment and management | ||

| Used short-acting bronchodilators in past 2 weeks | 38.1 | 42.0 |

| Used inhaled steroids in past 2 weeks | 63.5 | 68.1 |

| Uses correct medication for quick relief | 61.2 | 61.2 |

| Uses correct medication to prevent symptoms | 25.3 | 13.4* |

| Experienced side effects | 36.5 | 42.6 |

| Any smoke in home | 25.1 | 44.9* |

| Hours of smoke exposure/week, mean | 16.27 | 32.8* |

| Cat(s) in the home | 15.3 | 29.0* |

| Have written action plan | 26.0 | 18.8 |

| Use peak flow meter | 37.6 | 27.5 |

| Avoid triggers | 37.4 | 24.2* |

Data presented as %, unless indicated otherwise.

P<0.05

Health care use

The number of unscheduled doctor and emergency visits due to asthma was reduced in both groups (Table 3). The average number of doctor visits per year decreased at follow-up but was only statistically significant in the control group. When examining the percentage of children whose doctor visits were reduced, the control group showed a slightly higher improvement but the difference was not significant. The annual average of emergency department (ED) visits declined significantly at 12 months in the control group.

TABLE 3.

Level of control variables between Roaring Adventures of Puff (RAP) and control groups at three time points

| Variables | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health care use | |||||

| Unscheduled doctor visit in past year | RAP | 57.1 | 30.0 | 27.1 | |

| Control | 59.2 | 29.6 | 24.0 | ||

| Unscheduled doctor visits in past year, n (mean) | RAP | 1.8 | 1.56 | 1.2 | |

| Control | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | *† | |

| Emergency department visits in past year | RAP | 18.6 | 11.4 | 10.1 | |

| Control | 19.8 | 4.8 | 4.0 | ||

| Emergency department visits in past year, n (mean) | RAP | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Control | 0.36 | 0.12 | 0.072 | † | |

| Limitation of activity | |||||

| No missed school in past year | RAP | 29.3 | 55.2 | 53.4 | |

| Control | 47.2 | 69.8 | 64.2 | ||

| Missed school days in past year, n (mean) | RAP | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.0 | |

| Control | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | ||

| Limitation in nature of play | RAP | 40.0 | 27.1 | 18.6 | *† |

| Control | 33.9 | 21.8 | 21.1 | *† | |

| Limitation in amount of play | RAP | 45.7 | 44.3 | 42.0 | |

| Control | 56.8 | 39.2 | 36.8 | *† | |

| Medication use | |||||

| Used inhaled steroids | RAP | 62.0 | 64.0 | 69.0 | |

| Control | 64.3 | 64.3 | 69.8 | ||

| Used short-acting bronchodilators | RAP | 38.0 | 35.2 | 29.6 | |

| Control | 38.1 | 33.3 | 32.5 | ||

| Used <3 puffs short-acting bronchodilators | RAP | 32.4 | 73.5 | 77.4 | *† |

| Control | 50.7 | 67.6 | 70.1 | *† | |

| Environment | |||||

| Any smoke in the home | RAP | 35.7 | 25.7 | 31.4 | * |

| Control | 19.2 | 18.4 | 20.8 | ||

| Cat(s) in home | RAP | 15.7 | 15.7 | 14.3 | |

| Control | 15.1 | 13.5 | 15.9 | ||

| Animals in home | RAP | 40.0 | 35.7 | 43.5 | |

| Control | 31.0 | 38.9 | 37.3 | † | |

| Management behaviour | |||||

| Have written action plan | RAP | 28.6 | 38.6 | 28.6 | |

| Control | 25.0 | 25.0 | 19.2 | ||

| Use peak flow meter | RAP | 36.2 | 46.4 | 49.3 | † |

| Control | 38.9 | 42.1 | 46.4 | ||

| Avoid triggers | RAP | 34.8 | 81.8 | 75.4 | *† |

| Control | 39.3 | 66.1 | 66.4 | *† | |

| Improved understanding | RAP | 35.7 | 71.4 | 48.6 | *‡ |

| Control | 41.5 | 36.6 | 33.1 | ||

| Improved ability to control | RAP | 36.2 | 60.9 | 35.7 | *‡ |

| Control | 51.6 | 34.4 | 25.2 | *† | |

| Improved ability to cope | RAP | 24.6 | 46.4 | 28.2 | *‡ |

| Control | 30.3 | 26.4 | 16.3 | † | |

Data presented as %, unless indicated otherwise.

P<0.05 (baseline versus six months);

P<0.05 (baseline versus 12 months);

P<0.05 (RAP versus control at six months)

Limitation of activity

The intervention group improved in schools days missed due to asthma, compared with few changes in the control group in both the annual number of missed school days and per cent of children who had a decrease in missed school days at six and 12 months (Table 3). Both the intervention and control group had significant improvements in limitation in nature of play. However, the intervention group had improvement in limitation of activity by 54% at 12 months follow-up compared with 38% in the control group.

Medication use

The intervention group had inconsistent improvements in medication use (Table 3). The frequency of inhaled bronchodilator use improved in 50% of the children in the intervention group compared with 31% in the control group at six months. The number of children using less than three puffs per day of beta-2 agonist significantly increased at the six- and 12-month intervals for both groups; the intervention group had a 127% improvement at six months compared with 33% improvement in the control group. The use of inhaled steroids in the past two weeks did not improve in the control group over the two time periods. Many children were using inhaled corticosteroids only when they were sick. However, this ‘as needed’ use was reduced by 24% in the intervention group at six months compared with 7% in the control group, although this was not sustained at 12 months (RAP group: 51.1% at baseline to 38.8% at six months, to 53.5% at 12 months; control group: 68.3% at baseline to 63.8% at six months, to 60.8% at 12 months).

Management behaviour

Asthma management behaviour improved in the RAP group in several outcome measures (Table 3). Access to action plans improved by 35% for the RAP group compared with no improvement in the control group in the first six months. Surprisingly, after 12 months, the percentage of children with an action plan in both groups declined. The use of peak flow meters statistically increased in the RAP group by 28% and by 36% at the two time periods. Almost 50% improvements in avoidance of triggers were significantly different from baseline at both six and 12 months in the RAP group compared with approximately 25% improvement in the control group. Changes to the environment were less significant. The RAP group showed reduced smoking in the home at six months (28%) compared with 4% in the control group, despite the higher baseline in the RAP group. Cats or other animals in the home remained unchanged.

The intervention group scored significantly better than the control group for all global rating questions (Table 3). Parents of children in the RAP group indicated a significant increase in their understanding of asthma at six months and this improvement was significantly better than in the control group. The per cent of parents stating that their ability to control their child’s asthma improved over the past year was significantly greater than the RAP group and between groups at six months. This perceived improvement decreased in the control group at six and 12 months follow-up. In addition, parents of the intervention group stated that their ability to cope improved significantly at six months. At 12 months, parents in the control group exhibited a significant decrease in their perceived ability to cope with their child’s asthma.

Child-reported QOL

QOL improved in the intervention group in all categories compared with the control group (Table 4). At six months, RAP had significant improvements in three of the four QOL domains including symptoms, emotions and overall scores compared with the control group, which had significant improvement only in the emotions domain. Improvements from baseline to 12 months were statistically significant for all domains in the intervention group. The overall QOL score between the two groups was significantly better in the RAP group at 12 months. The overall QOL score at six and 12 months and the emotions score at 12 months for the intervention group (improvement of 0.5) could be considered clinically significant (1). The control group also had significant improvements at 12 months in the emotions and symptoms domain. There was no significant interaction between RAP and sex on childhood QOL outcomes. The univariate analysis of the variance for QOL ratings between the intervention and control group over the three time points, and controlling for the baseline difference of any smoking in the home, neared statistical significance only for the overall QOL domain (P=0.096, n=79).

TABLE 4.

Child-rated quality of life scores (on a 7-point scale for the past two weeks) for Roaring Adventures of Puff (RAP) and control groups at three time points

| Quality of life ratings | Group | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | P* | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity level | RAP | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.9 | ‡ | – |

| Control | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.2 | – | – | |

| Symptoms | RAP | 5.8 | 6.2 | 5.2 | §‡ | – |

| Control | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.1 | ‡ | – | |

| Emotions | RAP | 5.6 | 6.0 | 6.1 | §‡ | – |

| Control | 5.3 | 5.7 | 6.3 | §‡ | – | |

| Overall | RAP | 5.2 | 5.8 | 5.9 | §‡ | ¶ |

| Control | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.9 | – | – |

Pre- versus postintervention;

Intervention versus control;

Baseline versus 12 months, P<0.05;

Baseline versus six months, P<0.05;

Intervention versus control at 12 months, P<0.05

DISCUSSION

The RAP group showed an overall improvement in outcome measures at six and 12 months and significant improvements from baseline to at least one time period in select variables. This included any smoke in the home, use of peak flow meters, improved understanding of asthma, ability to cope and asthma control, and QOL domains including activity, emotions, symptoms and overall. Improvements were significantly greater in the RAP intervention group from baseline to six months compared with the control group in parent’s perceived understanding and ability to cope with and control asthma, and overall QOL. Some improvements were seen in both groups, likely due to differences in the intervention and control groups at baseline, and participants and those lost at follow-up.

A significant outcome from the present study is the extent to which RAP improved the child’s perception of their QOL, including well-being and functional impairment of everyday life activities. Statistically significant improvement in symptoms, emotions and overall domain scores were seen at six months, and all domain scores continued to significantly increase at 12 months. Clinical significance (a difference of greater than 0.5 between pre- and postscores [1]) was seen in the overall QOL domain at both time periods for the intervention group.

High importance is placed on measuring QOL in children with asthma (28). Some studies have suggested that QOL is predicted by the child’s level of anxiety (29). School-age children are sensitive to the actions and attitudes of their peers, and children with asthma often feel isolated and different (1). These beliefs and feelings can impact disease management behaviour (28). We suggest that participation in RAP with school peers helped individuals recognize their involvement in the social group and, in turn, improved their QOL. This repeat exposure to asthma issues in a group setting allows children to share their feelings, work through various emotions and build confidence as they practice managing asthma in various situations.

Indicators of management behaviour significantly improved in association with the program. This was a key objective of RAP. Self-efficacy and self-regulation can have a powerful impact on whether and how a behaviour is expressed (27,28). Therefore, strategies that were designed to improve behaviour were used. For example, to help gain confidence in using their action plan, ‘Puff’, the Asthmasaurus puppet, modelled its use and a game of charades called ‘lights-camera-action’ reinforced the key principles. An asthma diary helped them record the impact of the action plan, and follow-up discussions with peers praised appropriate behaviours and gave feedback on their accomplishments.

Limitations

A key limitation of the study was the size difference between groups, and the differences in dropouts and participants. Those that did not complete the questionnaires appeared to have more problems with their asthma and more smoke in the home. Because our unit of randomization was the school and not the students, it is possible that selection bias may have occurred.

Another limitation is the higher exposure to smoke in the home in the intervention group. Studies have suggested that smokers tend to experience higher stress (30), increased airway inflammation (31), are less likely to participate in education programs (12), have poor asthma knowledge and skills (32), are less likely to seek health care (33) and have worse outcomes after patient education (34). Future research needs to explore whether a targeted intervention for children and their parents who smoke would be efficacious.

The measurement tools that we used may not have been appropriately targeted or responsive enough to determine the full impact of the program. Qualitative data may have provided more information about the perceptions of the child and parent, how the program affected their lives and whether we measured what was most important to the patient.

Practice implications

The RAP program is an effective way to influence children with asthma at an early age and in a peer setting. A secondary goal of the program was to influence the child supports, such as parents, school staff, clinicians and friends, because these individuals are important targets in change behaviour. The present study prompted a pilot study and an initiative that examines how students with asthma can be better supported in schools. The RAP implementation guide and training program for instructors is now available online (26).

RAP attempted to promote communication between parent and child. We did this by offering a parent session, encouraging the child to share what they learned, and asked parents to learn from the child and sign the ‘fun book’ after each session. Studies have shown that parent reports can significantly differ from those of the child (35). In a subsequent paper, we identify discordance between the parent and children ratings of QOL in this study population (36). This difference between parent and child ratings was improved after RAP, emphasizing the importance of collecting data from and educating both the parent and child. Clearly, educators should consider the best strategies to optimize parent/child communication.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the RAP program had a modest effect on patient outcomes and generated enormous interest and positive feedback from children, parents and schools. By reaching not just the child but the child’s immediate care and support community, we likely had a broader impact than what we undertook to measure. Additional understanding of what impact the program had on creating a supportive environment to help sustain and reinforce the program objectives would help in making improvements. The foundations developed from our research in a school setting have helped to strengthen our partnership with schools in asthma care, including the development of school asthma guidelines linked with ongoing health care support.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank participating RAP instructors, health regions, schools, parents, teachers and children for making this study possible. They thank the Childhood Asthma Foundation of Canada for supporting this work and the expansion of RAP to other communities. The authors thank Dr A Senthilselvan, Public Health Sciences, University of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta), for his support in statistical analyses. All patient/personal identifiers have been removed.

Footnotes

FUNDING: Funded by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research – Health Research Fund.

DISCLOSURE: The authors disclose no financial interests associated with this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ, Griffith LE, Townsend M. Measuring quality of life in children with asthma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:35–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00435967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lava J, Moore R, Li F, El-Saadany S. Childhood asthma in sentinel health units: Report of the Student Lung Health Survey results 1995–1996. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.FitzGerald JM, Boulet LP, McIvor RA, Zimmerman S, Chapman KR. Asthma control in Canada remains suboptimal: The Reality of Asthma Control (TRAC) study. Can Respir J. 2006;13:253–9. doi: 10.1155/2006/753083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulet LP, Becker A, Berube D, Beveridge R, Ernst P. Canadian asthma consensus report, 1999. CMAJ. 1999;161:s1–s62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGhan SL, MacDonald C, James DE, et al. Factors associated with poor asthma control in children aged five to 13 years. Can Respir J. 2006;13:23–9. doi: 10.1155/2006/149863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark NM, Gong M. Management of chronic disease by practitioners and patients: Are we teaching the wrong things? BMJ. 2000;320:572–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman BJ, Bonner S, Evans D, Mellins RB. Self-regulating childhood asthma: A developmental model of family change. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:55–71. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans D, Mellins R, Lobach K, et al. Improving care for minority children with asthma: Professional education in public health clinics. Pediatrics. 1997;99:157–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward A, Willey C, Andrade S. Patient education provided to asthmatic children: A historical cohort study of the implementation of NIH recommendations. J Asthma. 2001;38:141–7. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin R, Choi BC, Chan BT, et al. Physician asthma management practices in Canada. Can Respir J. 2000;7:456–65. doi: 10.1155/2000/587151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkhart PV, Dunbar-Jacob JM, Rohay JM. Accuracy of children’s self-reported adherence to treatment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fish L, Wilson SR, Latini DM, Starr NJ. An education program for parents of children with asthma: Differences in attendance between smoking and nonsmoking parents. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:246–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark N, Jones P, Keller S, Vermeire P. Patient factors and compliance with asthma therapy. Respir Med. 1999;93:856–62. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(99)90050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris GS, Shearer AG. Beliefs that support the behavior of people with asthma: A qualitative investigation. J Asthma. 2001;38:427–34. doi: 10.1081/jas-100001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark NM, Gong M, Schork MA, et al. Long-term effects of asthma education for physicians on patient satisfaction and use of health services. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:15–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a04.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haby MM, Waters E, Robertson CF, Gibson PG, Ducharme FM. Interventions for educating children who have attended the emergency room for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD001290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGhan SL, Cicutto LC, Befus AD. Advances in development and evaluation of asthma education programs. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:61–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000146783.18716.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guevara JP, Wolf FM, Grum CM, Clark NM. Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:1308–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson PG, Henry RL, Vimpani GV, Halliday J. Asthma knowledge, attitudes, and quality of life in adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73:321–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan PW, DeBruyne JA. Parental concern towards the use of inhaled therapy in children with chronic asthma. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:547–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berge M, Munir AK, Dreborg S. Concentrations of cat (Fel d1), dog (Can f1) and mite (Der f1 and Der p1) allergens in the clothing and school environment of Swedish schoolchildren with and without pets at home. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998;9:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruzzese JM, Markman LB, Appel D, Webber M. An evaluation of Open Airways for Schools: Using college students as instructors. J Asthma. 2001;38:337–42. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cicutto L, Murphy S, Coutts D, et al. Breaking the access barrier: Evaluating an asthma center’s efforts to provide education to children with asthma in schools. Chest. 2005;128:1928–35. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGhan SL, Wells HM, Befus AD. The “Roaring Adventures of Puff”: A childhood asthma education program. J Pediatr Health Care. 1998;12:191–5. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5245(98)90044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGhan SL, Wong E, Jhangri GS, et al. Evaluation of an education program for elementary school children with asthma. J Asthma. 2003;40:523–33. doi: 10.1081/jas-120018785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Roaring Adventures of Puff An implementation guide for health care professionals Edmonton: Alberta Asthma Centre; 2006. <http://www.educationforasthma.com/> (Accessed on June 20, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning: An educational and ecological approach. 3rd edn. Mountain View: Mayfield; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Annett RD, Bender BG, Lapidus J, DuHamel TR, Lincoln A. Predicting children’s quality of life in an asthma clinical trial: What do children’s reports tell us? J Pediatr. 2001;139:854–61. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.119444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wamboldt FS, Ho J, Milgrom H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of household exposures to tobacco smoke and pets in children with asthma. J Pediatr. 2002;141:109–15. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Floreani AA, Rennard SI. The role of cigarette smoke in the pathogenesis of asthma and as a trigger for acute symptoms. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:38–46. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radeos MS, Leak LV, Lugo BP, Hanrahan JP, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Risk factors for lack of asthma self-management knowledge among ED patients not on inhaled steroids. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:253–9. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.21712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crombie IK, Wright A, Irvine L, Clark RA, Slane PW. Does passive smoking increase the frequency of health service contacts in children with asthma? Thorax. 2001;56:9–12. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. Does smoking affect the outcome of patient education and self-management in asthmatics? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:91–7. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Griffith LE, Feeny DH, Ferrie PJ. Children and adult perceptions of childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 1997;99:165–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandhane P, McGhan SL, Sharpe HM, et al. A child’s asthma quality of life rating does not significantly influence management of their asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:141–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]