Abstract

Three-dimensional protein structure determination is a costly process due in part to the low success rate within groups of potential targets. Conventional validation methods eliminate the vast majority of proteins from further consideration through a time-consuming succession of screens for expression, solubility, purification, and folding. False negatives at each stage incur unwarranted reductions in the overall success rate. We developed a semi-automated protocol for isotopically-labeled protein production using the Maxwell-16, a commercially available bench top robot, that allows for single-step target screening by 2D NMR. In the span of a week, one person can express, purify, and screen 48 different 15N-labeled proteins, accelerating the validation process by more than 10-fold. The yield from a single channel of the Maxwell-16 is sufficient for acquisition of a high-quality 2D 1H-15N-HSQC spectrum using a 3-mm sample cell and 5-mm cryogenic NMR probe. Maxwell-16 screening of a control group of proteins reproduced previous validation results from conventional small-scale expression screening and large-scale production approaches currently employed by our structural genomics pipeline. Analysis of 18 new protein constructs identified two potential structure targets that included the second PDZ domain of human Par-3. To further demonstrate the broad utility of this production strategy, we solved the PDZ2 NMR structure using [U-15N,13C] protein prepared using the Maxwell-16. This novel semi-automated protein production protocol reduces the time and cost associated with NMR structure determination by eliminating unnecessary screening and scale-up steps.

Keywords: robot, protein purification, Maxwell-16, NMR screening, protein structure initiative

Statement for Broader Audience

Using a compact commercial bench-top robot, we accelerated the process of 15N-labeled protein production for structural genomics NMR screening by more than 10-fold. Moreover, this automated purification strategy easily yielded sufficient material to support 3D structure determination, and we speculate that it could replace most conventional large-scale protein production pipelines.

A persistent bottleneck in structural genomics is the identification of soluble, folded domains suitable for 3D structure determination. Some of the major centers for structural genomics employ NMR spectroscopy in target selection1 and to augment X-ray crystallography as a complementary approach for 3D structure determination.2–5 To meet their annual production goals, thousands of proteins or domains must be screened,6 and this demands that traditional methods for molecular cloning and protein purification be adapted to parallel operation.7 Automated processing of nucleic acids is now routinely performed using commercial instruments, but parallelized robotic protein purification has typically been achieved with costly customized systems8 or at production scales that are insufficient for screening by NMR spectroscopy.

After target selection, cloning and transformation into an expression host, a small-scale expression study is conducted and analyzed by SDS-PAGE to select targets expressing high levels of soluble protein.9 Additional screening at this stage using 1D 1H NMR can identify folded proteins10 and predict success in crystallization trials,1 however the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum is essential for selection of candidates for structure determination by NMR. Production of 15N-labeled proteins for NMR is typically a secondary screen requiring large-scale expression and purification at a substantial cost per target. For abundantly expressed, soluble target proteins, a large-scale (0.5–1 L) culture of 15N-labeled protein is subjected to immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) purification and the dispersion, number, and intensity of signals in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum are evaluated before proceeding to production of the 13C/15N-enriched material needed to solve the structure. Production of 15N-labeled proteins is not easily parallelized and the entire screening process often requires two weeks to complete. Poorly behaved eukaryotic proteins often contain domains that would be amenable to structure determination if optimal sequence boundaries can be identified, but empirical analysis of multiple constructs is typically necessary. Protein production is thus a significant barrier to NMR-based screening of large numbers of domain constructs.

Cryogenic probe technology can dramatically increase the sensitivity of NMR measurements, but the enhancement is highly dependent on sample geometry. Improved mass sensitivity can be obtained with RF coils optimized for sample volumes smaller than the typical 5-mm diameter format.11 Microcoil probes using 1 or 1.7 mm sample cells have been used for 1D12 or 2D NMR screening,13 and this format is particularly valuable when protein yields are severely limiting. However, in our testing, the signal-to-noise ratio of an HSQC spectrum acquired on a 1.7-mm cryoprobe was 10-fold lower than one acquired on a 3-mm sample with a 5-mm cryoprobe using identical sample and acquisition parameters. Surprisingly, we observed that HSQC measurements using as little as 100 μg of 15N-labeled protein in a 3-mm sample cell yielded high quality spectra in 90 min or less, with little or no reduction in signal when compared with a sample of equal concentration in a 5 mm tube. Consequently, we investigated the possibility that small-scale expression testing and 2D NMR screening could be combined into a single high-throughput process. The Maxwell-16 (Promega, Madison, WI) is a small, relatively inexpensive bench top robot that enables the simultaneous lysis and IMAC purification of up to sixteen protein samples in ∼45 min. Cell lysis, resin binding, and four wash steps are performed in a seven-well cartridge followed by elution in a single cuvette [Fig. 1(a)]. An earlier study by Frederick et al. used the Maxwell-16 for expression testing of eukaryotic proteins but screening was limited to SDS-PAGE analysis.14 We speculated that an optimized approach to robotic purification could supply 15N-labled proteins in quantities sufficient for evaluation by 2D NMR.

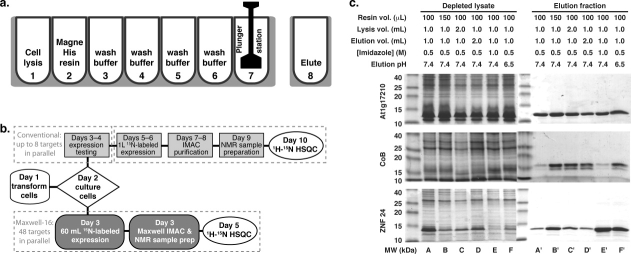

Figure 1.

Optimization of the Maxwell-16 buffer conditions and workflow. (a) IMAC purification is performed in a seven-well cartridge. Magnetic IMAC beads are conveyed by a magnetic plunger that also serves as a mixing device. Cell lysis is accomplished by the addition of FastBreak cell lysis buffer and gentle agitation by the plunger in well 1. The plunger retrieves the MagneHis resin from well 2 and returns to well one to adsorb the His-tagged protein. The bound protein undergoes four washes in wells 3–6. The purified protein is deposited in a single cuvette at the end of the procedure. The binding, wash and elution steps are repeated once in every Maxwell-16 purification. (b) Flowchart comparing conventional and automated protein purification workflows. In a conventional two-stage scheme for target screening, a workgroup of 24 targets is transformed, cultured, and evaluated for soluble expression by SDS-PAGE during week 1. In week 2, up to 8 targets may be selected for large-scale expression in 15N-enriched minimal medium, purification and 2D 1H-15N HSQC analysis. The optimized Maxwell-16 protocol parallelizes the protein purification process using 60 mL cultures, enabling a single technician to process up to 48 targets/week, reducing the total time for NMR screening by half, and increasing overall throughput by ∼10-fold. (c) Protein yields were enhanced by optimizing the volume of beads, lysis buffer, and elution buffer used. Additionally, we investigated how the elution buffer pH and imidazole concentration influenced release of protein from the MagneHis Ni-resin. SDS-PAGE analysis of the three test proteins revealed target-to-target variations. However, increasing the volume of MagneHis Ni-resin to 150 μL and lowering the pH of the elution buffer to 6.5 yielded the most consistent results. All studies were conducted with culture volumes corresponding to a total OD600 = 60.

Results and Discussion

Evaluation of more than 10,000 recombinant protein constructs by structural genomics projects over the last 10 years has led to a consensus strategy for expression screening and purification of structure targets.6 In the most common approaches to target validation, the scale of production and stringency of the selection criteria increase in a stepwise manner [Fig. 1(b)]. After transformation of the expression plasmids and initial bacterial cell culture of a group of targets, expression levels and protein solubility are analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Based on these results, a smaller number of targets (∼8) are selected for large-scale (0.5–1 L) 15N-labeled production, IMAC purification, and screening by 2D NMR. Targets that satisfy three spectral criteria (high chemical shift dispersion; peak count similar to the number of amino acid residues; uniform peak intensities) are evaluated as “HSQC+” and proceed to stability testing before finally being selected for 15N/13C labeling and 3D structure determination by NMR.

Automated parallel purification of 15N-labeled proteins for 2D NMR screening could significantly increase throughput relative to the conventional pipeline strategy if each cartridge of the Maxwell-16 generates enough material for acquisition of a 1H-15N HSQC spectrum. First, we sought to improve the yield of pure protein by maximizing the quantities of MagneHis beads (Promega, Madison, WI) and bacterial cell paste that could be reproducibly processed in a single cartridge (Supporting Information Fig. 1). The elution buffer was also varied to obtain the best combination of yield and purity for a set of three test proteins. As illustrated in Figure 1(c), optimal results were obtained using 0.15 mL of MagneHis beads, 50–60 mL of cell culture (OD600 ∼ 1), and an elution buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 500 mM imidazole, and 0.02% azide at pH 6.5. Target proteins for structural genomics are often produced as fusions linked by cleavage sites for thrombin, TEV protease, or other proteolytic enzymes. By modifying the standard Maxwell-16 protocol to incorporate an additional incubation period, we also found that it is possible to automate TEV digestion and separation of a target protein from its fusion partner (Supporting Information Fig. 2).

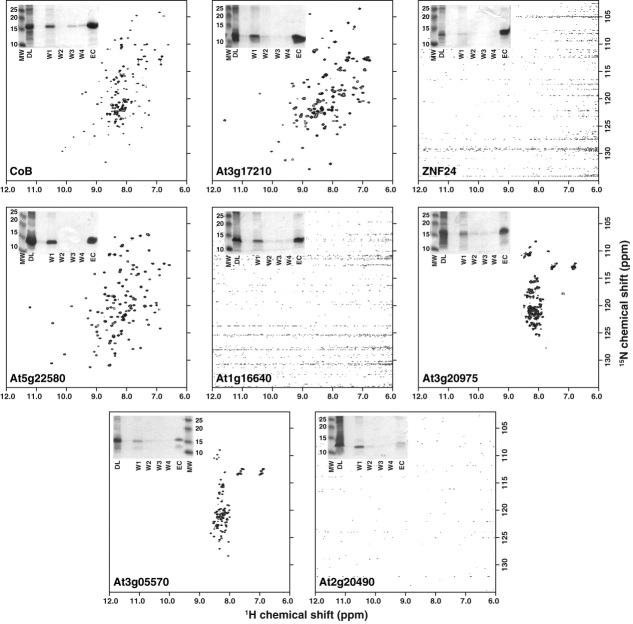

We tested the optimized Maxwell-16 protocol on a control workgroup of eight proteins previously characterized at the Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics (CESG), including five successful NMR structure targets15–19 and three unfolded proteins (Table I). Proteins were expressed in 15N-enriched medium and purified using the optimized Maxwell-16 protocol from a culture volume corresponding to a total OD600 = 60. Purified proteins were concentrated to a final volume of 0.2 mL in NMR buffer (20 mM Na2PO4, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl) and evaluated by acquiring 1D 1H and 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra (Fig. 2). Each protein from the control group was expressed at levels (0.2–0.5 mg) sufficient to record an HSQC spectrum except for one (At2g20490) that failed to purify using the optimized Maxwell-16 protocol. Two proteins, ZNF24 and At1g16640, were purified in quantities sufficient to collect HSQC spectra but precipitated during exchange into the selected NMR buffer.

Table I.

Maxwell-16 Screening Results for 8 Control Proteins

| Construct | Expression | Purification | HSQC |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoB | +++ | +++ | + |

| At3g17210 | +++ | +++ | + |

| ZNF24 | ++ | ++ | − |

| At5g22580 | +++ | +++ | + |

| At1g16640 | +++ | +++ | − |

| At3g29075 | ++ | ++ | unfolded |

| At3g05570 | ++ | + | unfolded |

| At2g20490 | + | − | − |

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional NMR analysis of control workgroup proteins. Samples from the control workgroup were subject to 1H-15N HSQC NMR. Spectra were acquired in ∼80 min using 16 transients per FID at 25°C on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz NMR equipped with a 5 mm TCI Cryoprobe. Purity of samples generated by the Maxwell-16 is illustrated by SDS-PAGE (inset). Each gel contains samples of depleted lysate (DL), each wash step (W1–W4) and pure protein in the elution cuvette (EC) prior to exchange into the selected NMR buffer.

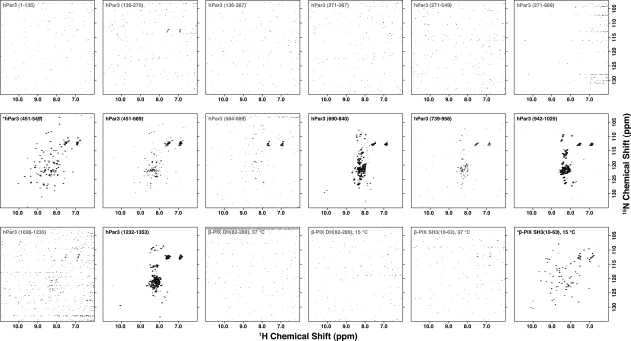

Rapid purification and screening using the Maxwell-16 permits empirical optimization of protein expression constructs. This is especially valuable when screening fragments of large proteins for which domain boundaries are defined imprecisely. To evaluate the utility of the Maxwell-16 in this application, we designed a domain workgroup consisting of a series of constructs that extracted individual or multiple PDZ domains from human Par-3 and the Dbl homology domain or Src homology 3 (SH3) domain from rat β-PIX. Once the expression constructs were in hand, 15N-labeled proteins were expressed and purified using the optimized Maxwell-16 protocol as summarized in Table II. Each construct was analyzed by 2D HSQC NMR where the β-PIX SH3 domain and the hPar-3 PDZ2 domain were judged to be folded, five constructs were unfolded, and 11 constructs contained no detectable signal (Fig. 3, Table II). SDS-PAGE analysis of the 18 constructs showed that three failed at the protein expression level, five additional proteins failed at the purification level and 10 yielded soluble protein suitable for NMR analysis. Of those 10 NMR samples, three yielded no detectable signal, consistent with aggregation or limited solubility.

Table II.

Maxwell-16 Screening of 18 Domain Constructs from hPar3 and β-PIX

| Construct | Expression temperature | Expression | Purification | HSQC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPar3 (1–135) | 37°C | +++ | ++ | N.S |

| hPar3 (136–270) | 37°C | ++ | ++ | N.S |

| hPar3 (136–367) | 37°C | +++ | − | N.S |

| hPar3 (271–367) | 37°C | ++ | − | N.S |

| hPar3 (271–549) | 37°C | − | − | N.S |

| hPar3 (271–689) | 37°C | + | − | N.S |

| hPar3 (451–549) | 37°C | +++ | +++ | + |

| hPar3 (451–689) | 37°C | + | + | − |

| hPar3 (584–689) | 37°C | +++ | +++ | N.S |

| hPar3 (690–840) | 37°C | multiple bands | multiple bands | − |

| hPar3 (739–958) | 37°C | − | − | − |

| hPar3 (942–1025) | 37°C | ++ | + | − |

| hPar3 (1026–1230) | 37°C | + | − | N.S |

| hPar3 (1232–1353) | 37°C | + | multiple bands | − |

| β-PIX DH (82–289) 8HT | 37°C | +++ | + | N.S |

| β-PIX DH (82–289) 8HT | 15°C | ++ | ++ | N.S |

| β-PIX SH3 (10–63) 8HT | 37°C | +++ | + | N.S |

| β-PIX SH3 (10–63) 8HT | 15°C | ++ | ++ | + |

All eighteen constructs were subjected to 1H-15N HSQC NMR. Spectra were graded as + for a folded protein, − for an unfolded or partially folded protein, or N.S. for a spectrum that did not show any signal. Gray shading indicates proteins that failed in expression or purification as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional NMR analysis of hPar-3 and β-PIX domain constructs. All 18 of the hPar-3 and β-PIX constructs were analyzed by 1H-15N HSQC NMR. Spectra were acquired in ∼80 min using 16 transients per FID at 25°C on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz NMR equipped with a 5 mm TCI Cryoprobe. HSQC spectra for constructs that are folded, partially folded or unfolded are labeled in black and those that contain no signal are labeled in gray. The two proteins that are suitable for NMR structure determination are indicated with an asterisk.

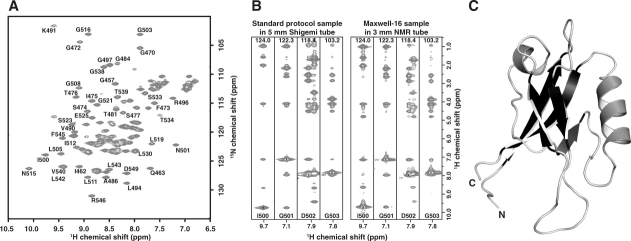

Our results indicate that 15N-labeled protein automatically isolated from 60 mL of bacterial cell culture using a single channel of the Maxwell-16 is sufficient for evaluation by 2D NMR in a structural genomics environment. For targets proceeding to 3D structure determination, a 0.5 mL sample of 13C/15N-labeled protein at a concentration ≥ 0.5 mM is typically obtained by a large-scale (1–2 L) cell culture and manual purification process. However, because HSQC screening in a 3-mm NMR tube requires a sample volume of only 0.2 mL with little or no signal loss relative to a 5-mm tube, we speculated that 13C/15N protein production on the Maxwell-16 might completely eliminate the need for a large-scale production pipeline. Based on the NMR screening results for hPar-3 domains, we expressed a 1 L 15N/13C culture of the second PDZ domain (PDZ2) and purified it on the Maxwell-16. Yield and purity of protein from equivalent 60 mL aliquots was uniform across all 16 channels (Supporting Information Fig. 3), each of which produced ∼0.4 mg of protein. The overall yield of PDZ2 purified using the Maxwell-16 was similar to conventional batch IMAC purification (∼8 mg/L). A 0.2 mL NMR sample containing 1 mM PDZ2 pooled from five Maxwell-16 channels was subjected to our 3D NMR data collection and structure determination protocol20 using a standard 5-mm cryogenic probe at 500 MHz [Fig. 4(a)]. While NMR data acquired on miniaturized samples using a microcoil probe suffers from reduced signal-to-noise ratios,21 spectra acquired on the 1 mM sample from robotic purification (0.2 mL in a 3 mm tube) were equal or superior to equivalent spectra acquired on the same instrument using 0.5 mL samples at the same protein concentration in a 5 mm tube [Fig. 4(b)]. We used automated methods to assign all 1H, 15N, and 13C shifts and solve the structure [Fig. 4(c)] to high resolution (Table III).

Figure 4.

Validation of the optimized Maxwell-16 protocol. (a) An assigned 1H-15N-HSQC of hPar3-PDZ2 shows 113 of 114 expected resonances. Data collection was done at 25°C in 3 mm sample cells with 4 transients per FID using a 1 mM sample of hPar3 PDZ2 in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5 containing 50 mM sodium chloride, 0.02% sodium azide, and 10% (v/v) 2H2O. (b) Comparison of four 15N-edited 3D NOESY-HSQC strips from spectra collected on hPar3 PDZ2 (1 mM) prepared by a conventional large-scale production protocol (left) or the Maxwell-16 protocol (right). Data for the standard sample was acquired in a 5-mm Shigemi tube at 600 MHz, whereas data collection for the Maxwell-16 sample was acquired in a 3-mm NMR tube at 500 MHz with equal data collection times. Spectra of equivalent or higher quality were obtained from the Maxwell-16 sample despite a 2.5-fold reduction in the active NMR sample by mass and volume. Similar results were observed for the 3D triple-resonance experiments. (c) Ribbon diagram of the hPar3 PDZ2 NMR structure solved protein generated by five channels of the Maxwell-16. Structural statistics for the NMR ensemble are presented in Table III.

Table III.

Statistics for the 20 hPar3-PDZ2 Conformers

| Experimental constraints | |

| Distance constraints | |

| Long | 520 |

| Medium [1 < (i − j) ≤ 5] | 178 |

| Sequential [(i − j) = 1] | 296 |

| Intraresidue [i = j] | 351 |

| Total | 1318 |

| Dihedral angle constraints (φ and ψ) | 99 |

| Average atomic R.M.S.D. to the mean structure (Å) | |

| Residues 10-29, 40-98 | |

| Backbone (Cα, C′, N) | 0.47 ± 0.07 |

| Heavy atoms | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

| Deviations from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bond lengths RMSD (Å) | 0.018 |

| Torsion angle violations RMSD (°) | 1.4 |

| WHATCHECK quality indicators | |

| Z-score | −1.36 ± 0.13 |

| RMS Z-score | |

| Bond lengths | 0.86 ± 0.03 |

| Bond angles | 0.70 ± 0.03 |

| Bumps | 0 ± 0 |

| Lennard-Jones energya (kJ mol−1) | −1850 ± 69 |

| Constraint violations | |

| NOE distance Number > 0.5 Å | 0 ± 0 |

| NOE distance RMSD (Å) | 0.027 ± 0.001 |

| Torsion angle violations Number > 5° | 0 ± 0 |

| Torsion angle violations RMSD (°) | 0.508 ± 0.092 |

| Ramachandran statistics (% of all residues) | |

| Most favored | 80.9 ± 2.9 |

| Additionally allowed | 15.2 ± 2.3 |

| Generously allowed | 1.4 ± 1.3 |

| Disallowed | 2.5 ± 0.9 |

Nonbonded energy was calculated in XPLOR-NIH.

Small-scale robotic purification is a robust alternative to conventional protein production schemes that permits rapid expression screening of many different protein targets or large panels of related domain constructs.8 While it may not be necessary or advisable to acquire NMR data on every target (e.g., completely insoluble proteins or those that fail to express), the cost of 15N enrichment in a 50 mL culture is less than one dollar per target and the HSQC spectrum is the most critical step in validation for 3D structure determination. By linking expression testing with NMR screening in a single process, the most promising candidates can be identified more rapidly and at lower cost. Importantly, we showed that a small-scale robotic purification strategy could replace a large-scale structural genomics pipeline by solving the NMR structure of a PDZ domain prepared using the Maxwell-16. While an additional polishing step would be advisable in some instances, the optimized yield from a single Maxwell-16 cartridge (∼0.5 mg) is sufficient for nanoliter-scale crystallization screening and this approach could also be adapted to boost structure production by X-ray crystallography.

Materials and Methods

Expression of recombinant proteins

Expression vectors for CoB,17 At3g17210,22 At5g22580,15 At1g16640,19 and ZNF2418 were constructed as previously described. Expression vectors for At3g29075 and At3g05570 were cloned into pET15b by the CESG as described for At3g17210 and At5g22580.15,22 At2g20490 was cloned into a modified pQE30 vector as described for CoB.17

The identification of domain boundaries in β-PIX and hPar-3 was facilitated by sequence alignment of homologs and previously published works. Selected domains were PCR amplified from full-length clones using a 5′ primer containing a BamHI restriction site and a 3′ primer containing a HindIII. PCR products were cut with BamHI and HindIII, gel purified and ligated into a pQE30 vector (Qiagen) modified to contain a (His)8 metal affinity tag and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease site for removal of the affinity tag.19 All expression vectors were verified by DNA sequencing. A full-length rat β-PIX clone was kindly provided by Dr. Andrey Sorokin (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI), and the full-length human Par-3 was kindly provided by Dr. Ian Macara (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA).

Expression

The pQE based and pET based expression constructs were transformed into E. coli strain SG13009[pRPEP4] (Qiagen) and BL21(DE3), respectively. Cell were grown in shake flasks using LB media containing the appropriate antibiotics until the cell density reached OD600= 0.7. Protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 1 mM. Final OD600 values ranged from 0.8–1.8. Following induction, incubation of the cells was continued for 5 h at 37°C or for 20 h at 15°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 min. Cell pellets were stored at −80°C. For uniform 15N labeling, cells were grown in M9 media containing 15N-ammonium chloride as the sole nitrogen source. Uniform 15N/13C labeling was accomplished by providing 13C-glucose as the sole carbon source concurrent with 15N-ammonium chloride.

Optimization of the Maxwell-16 protocol

The Maxwell-16 utilizes a seven-well cartridge and a separate elution cuvette to complete the automated purification of His-tagged proteins using MagneHis resin (Promega). Initial purification studies utilized a cell pellet from 50–60 mL of cell culture resuspended in 950 μL of resuspension buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 300 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole, 0.1% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsufonyl fluoride, and 50 μg of DNase) and 110 μL of FastBreak cell lysis solution (Promega). The cell suspension was placed in the first well of the Maxwell-16 cartridge. Well 2–6 contained 1 mL of wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 300 mM sodium chloride, and 10 mM imidazole), with 30 μL of MagneHis resin added to well 2. The elution cuvette contained 1 mL of elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.4, 300 mM sodium chloride, 500 mM imidazole, and 0.02% sodium azide) and well 7 contained the plunger. The automated protein purification protocol was selected from the Maxwell-16 menu and the results were evaluated by SDS-PAGE. To improve the yield of purified protein, the volume of MagneHis resin and the volume and composition of the wash and elution buffers were evaluated using ZNF24, At1g17210, and CoB as test cases. These optimizations resulted in two modifications to our initial protocol. First, the highest yields of purified protein were obtained using 150 μL of MagneHis resin. Second, the pH of the elution buffer was lowered from 7.4 to 6.5. All the subsequent purifications of isotopically labeled proteins for NMR were done using 50–60 mL of cell culture and the modified Maxwell-16 protocol. Yields of pure protein from a single cartridge determined by BCA assay or absorbance at 280 nm ranged from 0.2–0.5 mg, corresponding to 4–10 mg/L. Upon completion of the Maxwell-16 protocol, purified proteins were buffer exchanged into 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5 containing 50 mM sodium chloride, 0.02% sodium azide, and 10% (v/v) 2H2O and concentrated to a final volume of 200 μL.

NMR spectroscopy

1D 1H and 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra were acquired at 25°C in 3 mm sample cells on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm triple-resonance CryoProbe™. All HSQCs were collected with 16 transients per FID and processed with NMRPipe software.23

Structure determination

All 3D NMR data was acquired on a Bruker 500 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm triple-resonance CryoProbe™. The uniformly 15N/13C-hPar3 PDZ2 sample was prepared at a concentration of 1 mM in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5 containing 50 mM sodium chloride, 0.02% sodium azide and 10% (v/v) 2H2O and placed in a 3 mm sample cell. Backbone resonance assignments were verified from our previous structure determination using 3D HNCO, HNCA, and HNCACB spectra. Sidechain assignments were verified using HCCH-TOCSY data and a 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectrum optimized for aromatic groups. Distance constraints were obtained from 3D 15N-edited NOESY-HSQC and 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra (τmix = 80 ms). Backbone ψ and φ dihedral angle constraints were generated from secondary shifts of the 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, and 15N nuclei shifts by the program TALOS.24 Initial structures were generated using the NOEASSIGN module of the torsion angle dynamics program CYANA,25,26 followed by iterative manual refinement to eliminate consistently violated restraints. Of the final 100 structures calculated, the 20 conformers with the lowest target function values were selected and subjected to a molecular-dynamics protocol in explicit solvent using XPLOR-NIH.27 All time-domain NMR data and chemical shift assignments have been deposited in BioMagResBank (accession code: 16520) and the Protein Data Bank (accession code: 2kom).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donna Baldisseri (Bruker BioSpin) for data acquisition on a 1.7-mm CryoProbe®.

References

- 1.Page R, Peti W, Wilson IA, Stevens RC, Wuthrich K. NMR screening and crystal quality of bacterially expressed prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins in a structural genomics pipeline. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1901–1905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408490102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder DA, Chen Y, Denissova NG, Acton T, Aramini JM, Ciano M, Karlin R, Liu J, Manor P, Rajan PA, Rossi P, Swapna GV, Xiao R, Rost B, Hunt J, Montelione GT. Comparisons of NMR spectral quality and success in crystallization demonstrate that NMR and X-ray crystallography are complementary methods for small protein structure determination. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16505–16511. doi: 10.1021/ja053564h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yee AA, Savchenko A, Ignachenko A, Lukin J, Xu X, Skarina T, Evdokimova E, Liu CS, Semesi A, Guido V, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. NMR and X-ray crystallography, complementary tools in structural proteomics of small proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16512–16517. doi: 10.1021/ja053565+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips GN, Jr, Fox BG, Markley JL, Volkman BF, Bae E, Bitto E, Bingman CA, Frederick RO, McCoy JG, Lytle BL, Pierce BS, Song J, Twigger SN. Structures of proteins of biomedical interest from the Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2007;8:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s10969-007-9023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama S, Hirota H, Kigawa T, Yabuki T, Shirouzu M, Terada T, Ito Y, Matsuo Y, Kuroda Y, Nishimura Y, Kyogoku Y, Miki K, Masui R, Kuramitsu S. Structural genomics projects in Japan. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(Suppl):943–945. doi: 10.1038/80712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graslund S, Nordlund P, Weigelt J, Hallberg BM, Bray J, Gileadi O, Knapp S, Oppermann U, Arrowsmith C, Hui R, Ming J, dhe-Paganon S, Park HW, Savchenko A, Yee A, Edwards A, Vincentelli R, Cambillau C, Kim R, Kim SH, Rao Z, Shi Y, Terwilliger TC, Kim CY, Hung LW, Waldo GS, Peleg Y, Albeck S, Unger T, Dym O, Prilusky J, Sussman JL, Stevens RC, Lesley SA, Wilson IA, Joachimiak A, Collart F, Dementieva I, Donnelly MI, Eschenfeldt WH, Kim Y, Stols L, Wu R, Zhou M, Burley SK, Emtage JS, Sauder JM, Thompson D, Bain K, Luz J, Gheyi T, Zhang F, Atwell S, Almo SC, Bonanno JB, Fiser A, Swaminathan S, Studier FW, Chance MR, Sali A, Acton TB, Xiao R, Zhao L, Ma LC, Hunt JF, Tong L, Cunningham K, Inouye M, Anderson S, Janjua H, Shastry R, Ho CK, Wang D, Wang H, Jiang M, Montelione GT, Stuart DI, Owens RJ, Daenke S, Schutz A, Heinemann U, Yokoyama S, Bussow K, Gunsalus KC. Protein production and purification. Nat Methods. 2008;5:135–146. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lesley SA. Parallel methods for expression and purification. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:767–785. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesley SA. High-throughput proteomics: protein expression and purification in the postgenomic world. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;22:159–164. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyler RC, Aceti DJ, Bingman CA, Cornilescu CC, Fox BG, Frederick RO, Jeon WB, Lee MS, Newman CS, Peterson FC, Phillips GN, Jr., Shahan MN, Singh S, Song J, Sreenath HK, Tyler EM, Ulrich EL, Vinarov DA, Vojtik FC, Volkman BF, Wrobel RL, Zhao Q, Markley JL. Comparison of cell-based and cell-free protocols for producing target proteins from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome for structural studies. Proteins. 2005;59:633–643. doi: 10.1002/prot.20436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peti W, Etezady-Esfarjani T, Herrmann T, Klock HE, Lesley SA, Wuthrich K. NMR for structural proteomics of Thermotoga maritima: screening and structure determination. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2004;5:205–215. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029055.84242.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voehler MW, Collier G, Young JK, Stone MP, Germann MW. Performance of cryogenic probes as a function of ionic strength and sample tube geometry. J Magn Reson. 2006;183:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peti W, Page R, Moy K, O'Neil-Johnson M, Wilson IA, Stevens RC, Wuthrich K. Towards miniaturization of a structural genomics pipeline using micro-expression and microcoil NMR. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2005;6:259–267. doi: 10.1007/s10969-005-9000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossi P, Swapna GV, Huang YJ, Aramini JM, Anklin C, Conover K, Hamilton K, Xiao R, Acton TB, Ertekin A, Everett JK, Montelione GT. A microscale protein NMR sample screening pipeline. J Biomol NMR. 2009;46:11–22. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frederick RO, Bergeman L, Blommel PG, Bailey LJ, McCoy JG, Song J, Meske L, Bingman CA, Riters M, Dillon NA, Kunert J, Yoon JW, Lim A, Cassidy M, Bunge J, Aceti DJ, Primm JG, Markley JL, Phillips GN, Jr., Fox BG. Small-scale, semi-automated purification of eukaryotic proteins for structure determination. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2007;8:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s10969-007-9032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornilescu G, Cornilescu CC, Zhao Q, Frederick RO, Peterson FC, Thao S, Markley JL. Solution structure of a homodimeric hypothetical protein, At5g22580, a structural genomics target from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biomol NMR. 2004;29:387–390. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000032525.70677.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lytle BL, Peterson FC, Kjer KL, Frederick RO, Zhao Q, Thao S, Bingman C, Johnson KA, Phillips GN, Jr, Volkman BF. Structure of the hypothetical protein At3g17210 from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:397–400. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000015385.54050.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lytle BL, Peterson FC, Qiu SH, Luo M, Zhao Q, Markley JL, Volkman BF. Solution structure of a ubiquitin-like domain from tubulin-binding cofactor B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46787–46793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noll L, Peterson FC, Hayes PL, Volkman BF, Sander T. Heterodimer formation of the myeloid zinc finger 1 SCAN domain and association with promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1582–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waltner JK, Peterson FC, Lytle BL, Volkman BF. Structure of the B3 domain from Arabidopsis thaliana protein At1g16640. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2478–2483. doi: 10.1110/ps.051606305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markley JL, Bahrami A, Eghbalnia HR, Peterson FC, Ulrich EL, Westler WM, Volkman BF. Macromolecular structure determination by NMR spectroscopy. In: Gu J, Bourne PE, editors. Structural bioinformatics. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 93–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aramini JM, Rossi P, Anklin C, Xiao R, Montelione GT. Microgram-scale protein structure determination by NMR. Nat Methods. 2007;4:491–493. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytle BL, Peterson F, Kjer K, Frederick R, Zhao Q, Thao S, Bingman C, Johnson K, Philllips GJ, Volkman B. Structure of the hypothetical protein At3g17210 from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:397–400. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000015385.54050.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guntert P. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;278:353–378. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Güntert P, Mumenthaler C, Wüthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk CA, Bonvin AM, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50:496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]