Abstract

Canadian children’s health is influenced, in large part, by the living circumstances that they experience. These living circumstances – also known as the social determinants of health – are shaped by public policy decisions made by governmental authorities. While public policy should be focused on providing all Canadian children with the living circumstances necessary for health, it appears that Canada is far from achieving this goal. Instead, there are programs directed at Canada’s most severely disadvantaged families and children. While vital, these programs appear to achieve less than that which would be achieved if governmental action was designed to strengthen the social determinants of health for all children. Considering the governmental actions that would achieve this goal are well known – with rather little evidence of policy implementation – it is essential to understand the processes by which public policy is made. An important physician role – in addition to providing responsive health care services – is to become forceful advocates for public policy in the service of health. It is in the latter sphere that physician involvement may yield the strongest benefits for promoting children’s health.

Keywords: Public policy, Social determinants, Social paediatrics

Abstract

La santé des enfants canadiens est influencée en grande partie par leurs conditions de vie, qu’on appelle aussi déterminants sociaux de la santé, et qui sont façonnées par les décisions que prennent les autorités gouvernementales en matière de politiques publiques. Ces politiques publiques devraient viser à garantir à tous les enfants canadiens les conditions de vie dont ils ont besoin pour être en santé, mais il semble que le Canada soit loin d’atteindre cet objectif. Il existe plutôt des programmes destinés aux familles et aux enfants les plus défavorisés. Bien qu’ils soient essentiels, ces programmes semblent obtenir moins de résultats que si les mesures gouvernementales étaient conçues pour renforcer les déterminants sociaux de la santé de tous les enfants. Puisqu’on connaît bien les mesures gouvernementales qui permettraient de réaliser cet objectif, mais que peu de données en attestent l’implantation, il est essentiel de comprendre les processus par lesquels les politiques de santé sont adoptées. Le médecin, en plus de dispenser des services de santé réactifs, joue un rôle important : devenir un ardent défenseur des politiques publiques au service de la santé. C’est cette sphère de la participation des médecins qui peut être la plus bénéfique pour promouvoir la santé des enfants.

Part I of the present series provided an overview of children’s health in Canada. Numerous areas of concern were identified. Part II presented the mechanisms by which children’s health is shaped by their living circumstances. For many families with children, their living circumstances are clearly a cause for concern. Part III described specific aspects of children’s living circumstances – the social determinants of children’s health – that influence health and showed how their quality is determined, in large part, by public policy decisions made by governmental authorities. Numerous suggestions for improving children’s living circumstances were presented.

The present and final article of this series places the previous presentations into a broader societal context. It is focused on providing physicians with a framework by which they can understand how children-related public policy is made. Such understandings can then serve to support physician activity in the service of promoting children’s health.

PUBLIC POLICY AND CHILDREN’S HEALTH

More developed welfare states provide public policies that produce both higher quality and more equitable distribution of various social determinants of children’s health. For example, the social democratic Nordic nations of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden have public policies that are especially supportive of children’s health (1,2). In these nations, infant mortality and low birth weight rates, numerous indicators of children’s health and well-being, and the degree of inequality in child education and literacy outcomes are clearly superior to those in Canada and other nations with public policies that are less supportive of children’s health (1,2).

Even the conservative nations of continental Europe, such as Germany, France, Belgium and Holland, provide policies more supportive of children’s health than the liberal nations of Canada, Ireland, the United States and the United Kingdom (1,2). Whether it be more equitable distribution of income and wealth, greater employment, food and housing security, greater investment in employment training and concern with working conditions, or providing supports for families such as affordable early childhood education and care, these societal features lead to stronger indicators of childhood health and well-being (see addendum) (3–7).

In Canada, however, these lessons have not been learned. Improving children’s living circumstances would benefit health by reducing the experience of material and social deprivation, and enhancing psychosocial features of children’s communities, families and personal environments, thereby promoting cognitive, emotional and social development (see part II). Policy recommendations to improve children’s circumstances such as the following are commonplace (see part III) (8):

An enhanced child benefit for low-income families to a maximum of $5,100 (2007 dollars) per child

Restore and expand eligibility for employment insurance

Increase federal work tax credits to $2,400 per year

Establish a federal minimum wage of $10 per hour (2007 dollars)

Create a national housing plan including substantial federal funding for social housing

Establish a system of early childhood education and care that is affordable and available to all children (zero to 12 years of age)

Include a strong equity plan to ensure equal opportunities for all children and address systemic barriers

Develop appropriate poverty reduction targets, timetables and indicators for Aboriginal families, irrespective of where they live, in coordination with First Nations and urban Aboriginal communities

It would be reassuring to accept that Canadian policy failure could be attributed to advocates’ inability to create, disseminate, translate or exchange evidence with policymakers. This is clearly not the case. Canadian government, other institutional policy documents and Paediatrics & Child Health articles are chock full of these concepts and their implications for promoting children’s health and well-being (9).

CANADIAN POLICY RESPONSES FOCUS ON PROGRAMS FOR THE MOST DISADVANTAGED

Rather than implement policies to enhance the general health and well-being of the broad population of children, the Canadian policy response is frequently targeted programs such as prenatal medical care and Best Start programs (10). Not only are these programs available only to a minority of their intended targets, but these targeted programs are inadequate to reach large numbers of children who could benefit from universal programs. With regard to early childhood education and care (but the argument can be applied to a range of targeted programs):

Restricting early intervention initiatives to low-income neighbourhoods misses the majority of vulnerable children…. It is time to recognize that supporting the development of all children requires a system of high-quality ECEC [early child education and care] that is available and affordable to all families wishing to use it and to act on this recognition.

(10, page 40)

Clearly, there must be reasons – a lack of economic resources is not one of them because Canada is one of the wealthiest nations on the planet – other than a lack of evidence as to why child health-enhancing policies are not being implemented. I argue that Canadian governments have become reluctant to implement policies that would reduce the disparities in living circumstances to which Canadian children are exposed because it involves intervention in the operation of Canada’s market economy. After providing my reasons for this thinking, suggestions on how Canadian physicians can become involved in shifting this approach are presented.

SOCIETAL INSTITUTIONS AND LIVING CIRCUMSTANCES

Certain institutions of Canadian society shape the quality and variety of living circumstances children experience. Sociologists use the shorthand phrase ‘social inequality’ to refer to the important differences between people, which include their living circumstances:

Social inequality can refer to any of the differences between people (or the socially defined positions they occupy) that are consequential for the lives they lead, most particularly for the rights or opportunities they exercise and the rewards or privileges they enjoy.

(11, page 2)

Societal institutions shape patterns of relationships that are systematically associated with how rights, rewards and privileges are distributed. The primary institution shaping the distribution of these resources in Canada is the operation of the economic system (12). Canadians must gain employment, and the wages they earn determine, in large part, the quality of their living circumstances – the social determinants of health – to which their children are exposed. As pointed out in earlier articles, employment is especially important for Canadians because we receive fewer benefits and supports (ie, employment training, affordable child care, family benefits, social assistance, etc) from governments than citizens of other wealthy developed nations (13,14).

Societal institutions also include the state or government, and other agencies and organizations that may intervene in the operation of the economic system to influence citizens’ lives. In this manner, governments have the ability to improve, maintain or weaken the living circumstances children experience. Governments at all levels – federal, provincial/territorial, or local – influence children’s living circumstances either through action or inaction. The manner in which they choose to do so is usually a function of how elected representatives think of the role of governments.

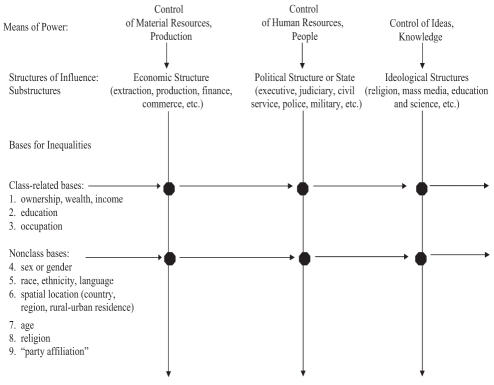

What exactly are the economic and political institutions that influence Canadian lives in general and children’s lives in particular? Grabb (11) identifies three primary bases for influencing the extent of ‘social inequality’ – or what others would term ‘differences in living circumstances’. The economic structure can operate in a manner that produces profound variations in wealth and income, influence and power – and I would add – health. Because all advanced economies are market economies, a simple indicator of the nature by which the economic system operates is the extent to which it is managed or controlled by state, governmental or other outside mechanisms, and how such interventions come about.

In all wealthy developed nations, the market economy leads to rather significant degrees of income inequality (2). However, in the nations that appear to more strongly support early child development, the government intervenes by providing numerous cash and in-kind benefits to low-income earners. These same nations are also more likely to make available free or low-cost child care, housing and training benefits for the most vulnerable. The result is a reduced disparity in living circumstances among children, with the resultant positive child health outcomes described in earlier parts of the present series (15–17).

In Canada and other liberal political economies, such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland, much less effort is expended in these directions (12). The result is that ownership, education and occupation profoundly shape the rewards that are provided by the economic system (11). If there are minimal laws shaping wage levels, employment security or working conditions, then these factors (ownership, education, etc) lead to widening inequalities in income, wealth and influence (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

The major means by which differences in families’ living conditions – social inequalities – come about. Adapted from reference 11

The political structure reinforces the operation of the economic system by enacting laws and regulations that codify these processes (11). These decisions act to legalize the disparity that exists in children’s living circumstances. Governments can enact laws that either enhance or reduce the economic resources, influence and power – the living circumstances – that members of various classes, status groups or associations come to hold. These could include employment and labour regulations, setting minimum wages, and making affordable child care and housing available.

Finally, the resultant differences in children’s living circumstances – and related health inequalities – come to be justified by ideological structures, the dominant ideas in society that explain – and usually justify – these differences (11). Key ideas that serve to justify social and health inequalities are individualism (we are all ultimately responsible for how our lives end up) versus communalism (we need to take care of each other) (18); market (everyone gets what they deserve) versus social justice (everyone should have enough income and wealth to live a decent life) (19); and an emphasis on the market (the exchange of commodities is the defining feature of our society) versus the polis (shared agreement on the organization of society through political action is paramount) as shaping the living conditions children attain (20).

OPERATION OF ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

In part III of the present series, key differences among advanced nations in overall governmental transfers as well as supports and benefits to working-age adults (including parents) were reviewed. Canada transfers less national resources to the citizenry through progressive taxation and program spending than most nations. Therefore, citizens are much more dependent on paid labour for securing their well-being. Usually, in such a situation, wages and benefits for the most vulnerable lag behind the situation in which governmental transfers are universal and more generous (3).

The means of improving children’s health would then be to draw on the lesson that has been taught by nations that do better for their children than we do. What exactly is this lesson? It is that governments must intervene by making public policies that assure adequate living circumstances for children (5). These policies involve a whole range of programs, supports, laws and regulations (21). Tax policy and transfers are especially important (22).

The Innocenti Research Centre produces an ongoing series of reports on children’s health and well-being with particular focus on poverty (1,2,23). Poverty is especially important to children’s health because it represents a clustering of disadvantage of a number of social determinants of children’s health. Tables 1 and 2 provide some of the conclusions reported by the Innocenti Research Centre that are relevant to the issues raised in the present series (24,25).

TABLE 1.

Policy-relevant conclusions from a league table of child poverty in rich nations, with added comments by the author relevant to Canada in parentheses

|

Adapted from reference 23. GNP Gross national product

TABLE 2.

Recommendations from an overview of child well-being in rich countries

|

Adapted from reference 1. OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

MOVING FORWARD: MODELS OF POLICY CHANGE

The past 20 years has seen a retreat by Canadian governments in promoting citizen economic security (9). Numerous analyses are available as to why this is the case, but the most compelling one is that Canadian governments have opted to let the marketplace determine the distribution of economic and social resources among the population. In contrast to the balance among the state (or government), labour sector and business sector – common during the 1960s and 1970s – the business sector has attained greater influence (26,27); greater balance is needed.

However, to address such a large undertaking may seem rather abstract and even more daunting. The value of the social determinants of health concept is that it provides manageable areas for citizen – and physician – activity in support of progressive public policy. Calling for living wages for parents, affordable quality child care, and improved income, food and housing security for families with children may appear to be more achievable.

There are two approaches as to how this may come about. The pluralist approach to public policy development sees policy development as being driven by the quality of ideas in the public policy arena (28). Those ideas judged as beneficial and useful will be translated into policies by governing authorities. This is the dominant model that is held out as representing the operation of public policy-making in an advanced democracy such as Canada. Yet, when presented with the arguments – based on evidence – proposed to advance children’s health, little seems to be happening. How can this inaction be explained?

The materialist approach to public policy development sees policy development as driven primarily by powerful interests who assure their concerns receive more attention than those not so situated (28). In Canada, it is argued that these powerful interests are based in the economic market sector and have powerful partners in the political arena. Perhaps it is not in the interest of this sector to have higher minimum wages and increased employment security for parents, or more comprehensive public health services such as home care or pharmacare?

The pluralist and materialist approaches provide differing explanations for understanding the present situation, and each proposes different means of moving a social determinants of health – in the service of promoting children’s health – agenda forward. The pluralist approach suggests the need for further research, knowledge dissemination and public policy advocacy, with the aim of convincing policy-makers to enact health-supporting public policy (28,29). Pluralism assumes that policy-makers will be receptive to these ideas. If this is the case in your local municipality or province, there is no shortage of suggestions for education, lobbying and advocacy activities in the service of improving the quality of the social determinants of children’s health (see part III of the present series).

If, however, your local authorities cannot be convinced by these arguments, the materialist model suggests the need to develop strong social and political movements, with the aim of forcing policy-makers to enact health-supporting public policy. Then the task is to build social movements that will force authorities – under threat of electoral defeat – to undertake positive policy change. These grass-roots activities will involve community education and development, building of social movements, and shifting perceptions on the role of governments in assuring citizen security.

THE ROLE OF PHYSICIANS

Physicians are well positioned to enter this debate. The Canadian Medical Association and the Canadian Paediatric Society have argued for the importance of addressing poverty (30). Physicians, nurses and other health care providers in Ontario have formed Health Providers Against Poverty (31). An Ontario Physicians Poverty Work Group has provided a five-part introduction for physicians on how to address determinants of health issues (32).

Physicians can focus on education and knowledge transmission. Such activities will not, by themselves, lead to positive public policy in support of the social determinants of children’s health, but will clearly assist other sectors that can be more actively engaged in public policy advocacy. However, the ultimate goal of these activities – whether we wish to state it publicly – is to build the social and political supports by which public policy in support of the social determinants of children’s health can be implemented.

Presenting the solid facts

The public remains woefully uninformed about the social determinants of children’s health. Canadian physicians can offer a message regarding the importance of improving living circumstances of children. At a minimum, materials can be placed in waiting rooms that clearly and objectively provide information on the social determinants of children’s health and what citizens can do to promote public policy in the service of their children’s health.

Physicians engaged in academic activities such as research and teaching can investigate and/or publicize findings from analysis of the social determinants of children’s health. This matter of information and knowledge transfer can focus on the direct social determinants of children’s health (such as poverty, housing and food insecurity, and social exclusion) and the indirect determinants (such as their parents’ employment security, working conditions and wages, among others). My short list of childhood afflictions shaped by these issues includes infant mortality, low birth weight, asthma, incidence and death from injuries, psychiatric and social problems, emergency room visits, school drop-out, delinquency and crime, and teenage pregnancy, among others (33).

Providing support for policy action

The second role is the most important but potentially the most difficult: supporting policy action in support of health. Implicit in supporting policy action is recognizing the important role politics play in these activities. There is increasing evidence that the quality of any number of social determinants of children’s health within a jurisdiction is shaped by the political ideology of governing parties (34).

In the past in Canada, progressive public policy related to children’s well-being was formed from all three major political parties. The question to be answered is “Which party is most likely now to address these issues?” Campaign 2000’s analysis (35) of federal party positions ranked parties in terms of their willingness to address child poverty: New Democratic Party (first), Liberal (second) and Conservative (third). Affordable universal child care, for example, is not on the current federal agenda of the Conservative party.

Internationally, the quality of the social determinants of children’s health is highest where there has been greater rule by social democratic parties (4), even conservative governments do better than liberal governments. It has also been documented that poverty rates and government support in favour of health – the extent of government transfers to families – is higher when the popular vote is more directly translated into political representation through proportional representation (36). Canada does not have proportional representation – the lack of which is associated with higher child poverty rates and less government action in support of children’s health. Proportional representation is important because it provides an ongoing influence of social democratic parties regardless of which party forms the government (37).

TOWARD THE FUTURE

Where does this knowledge of the role of politics in shaping the quality of the social determinants of health leave physicians?

Actions of physician associations

One avenue of action is through association action. As noted earlier, the Canadian Medical Association and Canadian Paediatric Association have, in the past, argued forcefully for action on the social determinants of children’s health. The Ontario Physicians Poverty Work Group and Health Providers Against Poverty provide opportunities for physicians to become engaged in the social determinants of children’s health. Without a doubt, there are other organizations and agencies working on these issues.

Political engagement

Physicians are also citizens who can vote and support particular political parties between and during political campaigns. Most Canadians are not involved in politics, and there is no reason to believe that physicians are much different than the average Canadian (38). In 2003, only 3% of Canadians volunteered for a political party, 6% participated in a demonstration or march, 21% attended a public meeting, 26% searched for political information and 27% signed a petition. The importance of the social determinants of children’s health should serve as a spur to increase participation among physicians.

Those in the best position to suggest future courses of action for physicians are the readers of Paediatrics & Child Health. There is no shortage of both health-related and other organizations and agencies with which you can work. The evidence seems clear: promoting the health of children requires the enactment of public policies that improve the living circumstances of children. To date, Canada has fallen short of many other nations. Improving the situation will require political action. Are physicians prepared to engage in the debate of what needs to be done?

Footnotes

ADDENDUM: Fraser Mustard reaches a similar conclusion with regard to early child development: “In Scandinavian countries, support for families and young children is much better than in Canada and the United States” (6, page 841). Clyde Hertzman comments, “Canadians working in early child development often ask themselves: ‘Why don’t we just give up and move to Sweden’” (7).

REFERENCES

- 1.Innocenti Research Centre . An Overview of Child Well-being in Rich Countries: A Comprehensive Assessment of the Lives and Well-being of Children and Adolescents in the Economically Advanced Nations. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Innocenti Research Centre . Child Poverty in Rich Nations, 2005 Report Card No 6. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael D. Canadian public policy and poverty in international perspective. In: Raphael D, editor. Poverty and Policy in Canada: Implications for Health and Quality of Life. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2007. pp. 335–64. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rainwater L, Smeeding TM. Poor Kids in a Rich Country: America’s Children in Comparative Perspective. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esping-Andersen G. A child-centred social investment strategy. In: Esping-Andersen G, editor. Why We Need a New Welfare State. Oxford; Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 26–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mustard F. Free market capitalism, social accountability and equity in early human (child) development. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:839–42. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.10.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertzman C. The 18-month well-baby visit: A commentary. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:843–4. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.10.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campaign 2000 . 2008 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Canada. Toronto: Campaign 2000; 2008. Family Security in Insecure Times: The Case for a Poverty Reduction Strategy for Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raphael D, Curry-Stevens A, Bryant T. Barriers to addressing the social determinants of health: Insights from the Canadian experience. Health Policy. 2008;88:222–35. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doherty G. Ensuring the best start in life: Targeting versus universality in early childhood development. Choices. 2007;13:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabb E. Theories of Social Inequality. 5th edn. Toronto: Harcourt Canada; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saint-Arnaud S, Bernard P. Convergence or resilience? A hierarchial cluster analysis of the welfare regimes in advanced countries. Current Sociology. 2003;51:499–527. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bambra C. Going beyond the three worlds of welfare capitalism: Regime theory and public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:1098–102. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eikemo TA, Bambra C. The welfare state: A glossary for public health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:3–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brady D. The politics of poverty: Left political institutions, the welfare state, and poverty. Social Forces. 2003;82:557–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leys C. Market-Driven Politics. London: Verso; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macarov D. What the Market Does to People: Privatization, Globalization, and Poverty. Atlanta: Clarity Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofrichter R. Health and Social Justice: A Reader on Ideology, and Inequity in the Distribution of Disease. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2003. The politics of health inequities: Contested terrain; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curry-Stevens A. When Markets Fail People. Toronto: Centre for Social Justice Foundation for Research and Education; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone D. Policy Paradox and Political Reason. Glenview: Scott, Foresman; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bambra C. The worlds of welfare: Illusory and gender blind? Social Policy and Society. 2004;3:201–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant T. Politics, public policy and population health. In: Raphael D, Bryant T, Rioux M, editors. Staying Alive: Critical Perspectives on Health, Illness, and Health Care. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2006. pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innocenti Research Centre . A League Table of Child Poverty in Rich Nations. Florence: Innocenti Research Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coburn D. Beyond the income inequality hypothesis: Globalization, neo-liberalism, and health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:41–56. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coburn D. Health and health care: A political economy perspective. In: Raphael D, Bryant T, Rioux M, editors. Staying Alive: Critical Perspectives on Health, Illness, and Health Care. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2006. pp. 59–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langille D. Follow the money: How business and politics shape our health. In: Raphael D, editor. Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives. 2nd edn. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2008. pp. 305–17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teeple G. Globalization and the Decline of Social Reform: Into the Twenty First Century. Aurora: Garamond Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks S, Miljan L. Theories of public policy. In: Brooks S, Miljan L, editors. Public Policy in Canada: An Introduction. Toronto: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 22–49. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright EO. The class analysis of poverty. In: Wright EO, editor. Interrogating Inequality. New York: Verso; 1994. pp. 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raphael D. Increasing poverty threatens the health of all Canadians. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:1703–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ending Poverty, Improving Health. Toronto: Health Providers Against Poverty; 2008. Health Providers Against Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ontario Physicians Poverty Work Group . Poverty and Health. Toronto: Ontario Medical Review; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raphael D. Poverty and health. In: Raphael D, editor. Poverty and Policy in Canada: Implications for Health and Quality of Life. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2007. pp. 205–38. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raphael D. The politics of poverty. In: Raphael D, editor. Poverty and Policy in Canada: Implications for Health and Quality of Life. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Incorporated; 2007. pp. 303–34. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campaign 2000 . Federal Election 2008: Addressing child and family poverty in Canada: Where do the parties stand? Toronto: Campaign 2000; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alesina A, Glaeser EL. Fighting Poverty in the US and Europe: A World of Difference. Toronto: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esping-Andersen G. Politics Against Markets: The Social Democratic Road to Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schellenberg G. General Social Survey on Social Engagement, Cycle 17: An Overview of Findings. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2003. 2004. [Google Scholar]