To the Editor: In 2009, Kapoor et al. and Arthur et al. published reports on the prevalence of the newly identified parvovirus, human bocavirus 2 (HBoV-2), in fecal samples (1,2). HBoV-1 had been discovered in 2005 (3), and reports indicate its possible role in respiratory diseases such as upper respiratory tract infections, lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), and in exacerbation of asthma (4); in these diseases, the virus co-infects with other respiratory viruses (5). Systemic infection with HBoV-1 and possible association of this virus with other diseases such as gastroenteritis, Kawasaki disease, and hepatitis have been reported (6–8). We looked for HBoV-2 in clinical samples from children with various diseases, including acute LRTIs, Kawasaki disease, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and hepatitis.

During September 2008–January 2009, a total of 212 nasopharyngeal aspirates were collected from 212 children (median age 8 months, range 1–59 months) hospitalized with acute LRTIs at Sanggyepaik Hospital in Seoul, South Korea. Previously, during January 2002–June 2006, a total of 173 serum samples had been obtained from children (age range 1 month–15 years) with hepatitis (hepatitis B, 20 samples; hepatitis C, 11 samples; unknown hepatitis, 31 samples), Kawasaki disease (12 samples), and Henoch-Schönlein purpura (18 samples) and from healthy children (same age range, 81 samples) (9). The study was approved by the internal review board of Sanggyepaik Hospital.

DNA was extracted from serum samples, and RNA and DNA were extracted from nasopharyngeal aspirates by using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH), respectively. All nasopharyngeal aspirates were tested by PCR for common respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus, as described previously (10). PCRs to detect HBoV-1 were performed by using primers for the nonstructural (NS) 1 and nucleocapsid protein (NP) 1 genes, as described previously (10). Additional PCRs for rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus (hCoV)-NL63, hCoV-OC43, hCoV-229E, hCoV HKU-1, WU polyomavirus, and KU polyomavirus were performed, as described, for HBoV-2–positive samples (10).

HBoV-2 was detected by performing first-round PCR with primers based on the NS gene, HBoV2-sf1, and HBoV2-sr1. Second-round PCR was performed by using primers HBoV2-sf2 and HBoVsr2, as described previously (1). The PCR products were sequenced by using an ABI 3730 XL autoanalyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The nucleotide sequences were aligned by using BioEdit 7.0 (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/BioEdit.html) and presented in a topology tree, prepared by using MEGA 4.1 (www.megasoftware.net).

Of the 212 samples tested, the following viruses were detected: human respiratory syncytial virus (in 124 [58.4%] samples), human rhinovirus (24 [11.3%]), influenza virus A (18 [8.4%]), adenovirus (10 [4.7%]), and parainfluenza virus (8 [3.7%]). HBoV-1 was not detected in the study population. HBoV-2 DNA was found in 5 (2.3%) of the 212 samples collected; all positive samples had been obtained in October 2008. The age range of the children with HBoV-2–positive samples was 4–34 months (median 24 months), and all were male. The diagnoses were bronchiolitis for 3 children and bronchopneumonia for 2. The most frequently codetected virus was human respiratory syncytial virus, found in 4 (80%) of 5 samples. One sample that was negative for respiratory syncytial virus and positive for HBoV-2 was negative for all other respiratory viruses.

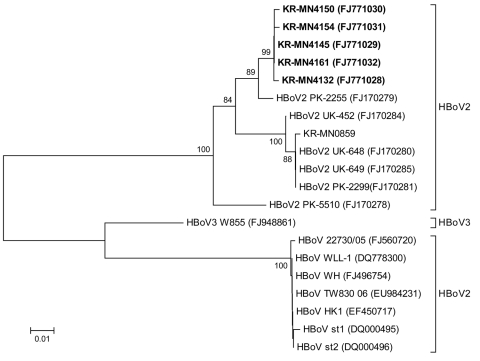

Nucleotide sequences were determined for the NS-1 gene, and phylogenetic analyses, which included HBoV-3, a new lineage designated by Arthur et al. (2), showed that the NS-1 gene was relatively well conserved and that there were 2 major groups of the virus, the UK strain and the Pakistan strain. HBoV-2 strains isolated from South Korea belonged to the HBoV-PK2255 (FJ170279) cluster (Figure).

Figure.

Phylogenetic analysis of nonstructural (NS) 1 gene sequences from human bocavirus 2 strains from Korea (KR), United Kingdom (UK), and Pakistan (PK), presented on a topology tree prepared by using MEGA 3.1 (www.megasoftware.net). Nucleotide alignment of a 417-bp portion of the NS1 gene was prepared by using BioEdit 7.0 (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/BioEdit.html). The nucleotide distance matrix was generated by using the Kimura 2-parameter estimation. Nodal confidence values indicate the results of bootstrap resampling (n = 1,000). Five strains from South Korea (FJ771028–32) are in boldface. Scale bar indicates estimated number of substitutions per 10 bases.

Recent studies have detected HBoV-1 in serum samples of children with Kawasaki disease and of an immunocompromised child with hepatitis (7,8). However, neither HBoV-1 nor HBoV-2 was detected in the 172 serum samples from 61 patients with hepatitis, 12 with Kawasaki disease, 18 with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, and 81 healthy children.

The absence of HBoV-1 in the samples examined was unexpected because HBoV-1 was detected in >10% of 558 respiratory samples collected from a demographically similar study population during the winter 2 years earlier (10). Future studies, with larger populations and over longer periods, are needed to delineate seasonal variations between HBoV-1 and HBoV-2.

We demonstrated HBoV-2 DNA in the respiratory tract secretions of children with acute LRTIs. In most positive samples, the virus was found in addition to other respiratory viruses. A limitation is that the study did not consider health control measures and other clinical disease such as gastroenteritis and was conducted for a short time. The role of HBoV-2 in LRTIs remains unclear; further studies are needed to clarify whether this virus is only shed from the respiratory tract or whether it replicates in the gastrointestinal tract.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by a research grant (2008) from Inje University.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Han T-H, Chung J-Y, Hwang E-S. Human bocavirus 2 in children, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2009 Oct [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/10/1698.htm

Reference

- 1.Kapoor A, Slikas E, Simmonds P, Chieochansin T, Naeem A, Shaukat S, et al. A newly identified species in human stool. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:196–200. 10.1086/595831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur JL, Higgins GD, Davidson GP, Givney RC, Ratcliff RM. A novel bocavirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Australian children. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000391. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12891–6. 10.1073/pnas.0504666102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kesebir D, Vazquez M, Weibel C, Shapiro ED, Ferguson D, Landry ML, et al. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1276–82. 10.1086/508213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissbrich B, Neske F, Schubert J, Tollman F, Blath K, Blessing K, et al. Frequent detection of bocavirus DNA in German children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:109. 10.1186/1471-2334-6-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vicente D, Cilla G, Montes M, Perez-Yarza EG, Perez-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:636–7. 10.3201/eid1304.061501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catalano-Pons C, Giraud C, Rozenberg F, Meritet JF, Lebon P, Gendrel D. Detection of human bocavirus in children with Kawasaki disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;113:1220–2. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kainulainen L, Waris M, Soderlund-Venermo M, Allander T, Jedman K, Russkanen O. Hepatitis and human bocavirus primary infection in a child with T-cell deficiency. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:4104–5. 10.1128/JCM.01288-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung JY, Han TH, Koo JW, Kim SW, Seo JK, Hwang ES. Small anellovirus infections in Korean children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:791–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han TH, Chung JY, Koo JW, Kim SW, Hwang ES. WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1766–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]