Abstract

To determine the effectiveness of ducks as sentinels for avian influenza virus (AIV) infection, we placed mallards in contact with wild birds at resting sites in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Infections of sentinel birds with different AIV subtypes confirmed the value of such surveillance for AIV monitoring.

Keywords: sentinel, avian influenza, active surveillance, wild birds, influenza, viruses, dispatch

As a consequence of infections of wild birds and poultry with highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) subtype H5N1, surveillance of wild birds for avian influenza viruses (AIVs) has intensified in Europe since 2005. Reporting of results is compulsory in the European Union (1,2). HPAIV surveillance includes investigation of dead or sick wild birds (3) with the aim of early detection of HPAIV (H5N1) complemented by sampling of healthy wild birds to monitor for low pathogenicity (LP) AIV strains (4). Previously, sentinel birds were used successfully to obtain information about AIV subtypes circulating in wild birds (5), but results of those studies are now outdated. Also, the effectiveness of sentinel birds has not yet been documented for AIV strains that emerged during the past decade.

We evaluated a sentinel approach to monitor the prevalence of HPAIV and LPAIV within an ecosystem, obtain information about seroconversion and duration of immunity after infection with AIV, and serve as an early warning system for the introduction of HPAIV (H5N1) and other notifiable AIVs (subtypes H5 and H7) to wild bird populations. Here we summarize results from a 2-year period of 3 international sentinel projects ongoing since 2006.

The Study

In 2006, multiple introductions and spread of HPAIV (H5N1) occurred in Europe, including the wetlands in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (3,4,6,7). For our study, we selected 5 locations with substantial and heterogeneous wild bird populations on the basis of HPAIV (H5N1) subtype detected during 2006. Sentinel stations were located around Lake Constance and in 2 other wetlands in Germany. The sentinel flocks at Lake Constance were situated in 1) Radolfzell (Möggingen), Germany (47°45′58′′N, 8°59′45′′E); 2) Altenrhein, Switzerland (47°29′25′′N, 9°32′45′′E); and 3) Bregenz-Thal (Rheindelta), Austria (47°30′60′′N, 9°38′55′′E). The 2 other stations were situated 4) on the Isle of Koos close to the Island of Rügen in Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany (54°10′13′′N, 13°24′11′′E) and 5) near the Oder Valley at Lake Felchow (Brandenburg), Germany, (53°03′09′′N, 14°08′06′′E) (Figure 1). After their wing feathers were clipped, 10–20 hand-bred adult mallard ducks (Anas plathyrhynchos) <1 year of age were placed in pens in natural water bodies, allowing continuous direct contact with wild water birds as previously described (5). Cloacal and oropharyngeal swabs and blood were taken from the mallards and tested negatively by using 1-step TaqMan real-time reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) or competitive nucleoprotein antibody ELISA (cNP ELISA) (ID-Vet, Montpellier, France; Anigen, MegaCorGmbH, Hörbanz, Austria) before their use as sentinels.

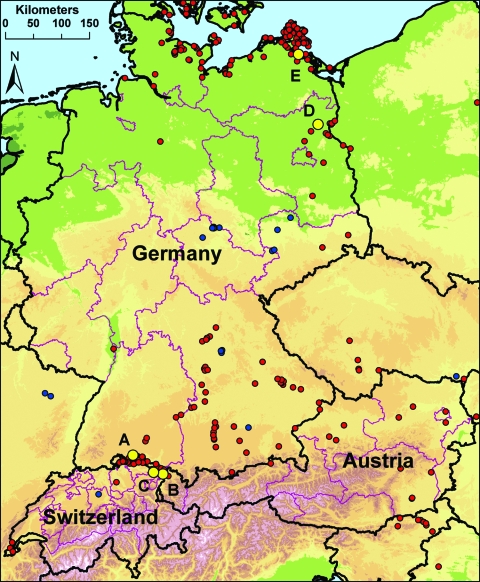

Figure 1.

Locations of sentinel duck flocks at 5 locations in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. A–C) Sites at Lake Constance: Radolfzell, Germany (A); Bregenz-Thal, Austria (B); and Altenrhein, Switzerland (C). D–E) Additional sentinel stations at Lake Felchow, Brandenburg, Germany (D), and Isle of Koos, Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany (E). Yellow dots mark the location of sentinel stations. Red dots mark detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) (H5N1) in dead wild birds in 2006, and blue dots in 2007. In 2008, HPAIV (H5N1) was not found in dead wild birds in any of the 3 countries but was found in a live pochard (Aythya ferina) from Switzerland/Lake Sempach (blue dot in Switzerland).

At all sentinel stations in Germany, we collected oropharyngeal and cloacal swab samples from the sentinels every 14 days starting in autumn 2006. Sampling at the station in Austria started in February 2007 and at the station in Switzerland in October 2007. Laboratory tests were conducted in accordance with the Diagnostic Manual for Avian Influenza of the European Union (8). RNA was isolated from swabs by using viral RNA kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany; Macherey-Nagel, Oensingen, Switzerland) and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for influenza virus matrix (M) or nucleocapsid protein (NP) gene fragments. In positive samples, H5-, N1- and H7-specific real-time RT-PCRs were used to identify or exclude respective subtypes (9,10). H5 and H7 isolates were pathotyped following the European Union directive (8). Direct hemagglutinin (HA) typing or sequencing of positive samples was carried out as previously described (7,11–13). The neuraminidase (NA) subtype was identified molecularly, by following the method of Fereidouni et al. (14). Simultaneously, we attempted virus isolation in embryonated chicken eggs from positive samples (8).

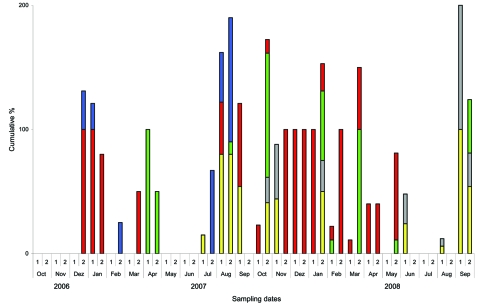

From October 2006 through September 2008, at least 23 specifiable AIV infections were detected at the sentinel stations by the fortnightly swabbing. After initial AIV introduction, virus was excreted during the following 1–3 sampling dates (Figure 2). All ducks at all sites tested positive at least once. Infections caused by AIV of 8 HA subtypes, including H5 and H7, and 6 NA subtypes, were found in clinically healthy sentinel birds (Tables 1, 2). Viral RNA and, in 44% of AIV cases, infectious virus also were recovered both from cloacal and oropharyngeal swabs. AIVs were subtyped as H1N1, H1Nx, H2N2, H2N5, H3N2, H3Nx, H3N8, H4N6, H5Nx, H6N5, H6N8, H7N3, H7Nx, and H9N2. Cycle threshold values ranged from 24 to 40. Pathotyping of H5 and H7 subtypes showed the exclusive presence of LP viruses. Additional AIVs were detected but could neither be isolated nor sequenced for subtype identification because of low loads of viral RNA. However, we did not detect H5, N1, and H7 subtypes by using real-time RT-PCR. Infections occurred most frequently from August through January (Figure 2; Table 1). Reinfection of the sentinels with the same subtype occurred in 2 of the sentinel flocks in Germany (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Months with positive results for sentinel birds over a 2-year period at 5 locations in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Sites at Lake Constance: Radolfzell, Germany (yellow); Bregenz-Thal, Austria (gray); and Altenrhein, Switzerland (green). Additional sentinel stations at Lake Felchow, Brandenburg, Germany (red), and Isle of Koos, Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany (blue). Bars indicate the cumulative percentage of sentinel birds tested positive at each of the 5 locations at the time of sampling (maximum 500% at all 5 stations). For example, in December 2006, all sentinel ducks at station 4, but only 30% of sentinels at station 5, were positive at the date of sampling. 1, days 1–15 of month; 2, day 16 through end of month.

Table 1. Detection of AIV by sampling of sentinel mallard ducks (Anas plathyrhynchos) at 5 locations in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria*†.

| Sentinel location | Date sampled | Ct range‡ | Duration virus excretion, d | HA subtype | NA subtype | Isolate | Sequence of HA-cleavage site (H5, H7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radolfzell, Germany |

2007 Aug | 29–37 | Min 28, max 42 | H6 | N8 | Yes | |

| 2007 Oct | 31–39 | Min 14, max 28 | H2 | N5 | Yes | ||

| H3 | N2 | Yes | |||||

| 2008 Jan | 33–38 | Punctual | H3 | N2 | Yes | ||

| 2008 Jun | 33–39 | Punctual | H3 | N2 | No | ||

| 2008 Sep |

33–39 |

Min 14, max 28 |

H3 |

N8 |

Yes |

|

|

| Altenrhein, Switzerland |

2007 Oct | 27–39 | Min 15, max 39 | ND§ | N2 | No | |

| 2007 Dec | 24–37 | Punctual | H2 | N2 | No | ||

| 2008 Aug |

29–34 |

Punctual |

H9 |

N2 |

No |

|

|

| Bregenz-Thal, Austria |

2007 Apr | 28–38 | Min 23, max 38 | H3 | ND¶ | No | |

| 2007 Oct | 22–40 | Min 12, max 26 | H9 | N2 | Yes | ||

| 2008 Jan | 27–38 | Min 14, max 42 | H1 | N1 | No | ||

| 2008 Mar |

25–35 |

Min 14, max 42 |

H7 |

ND¶ |

No |

PEIPKGR GLF |

|

| Lake Felchow, Brandenburg, Germany |

2006 Dec | 27–35 | Min 22, max 36 | H6 | N2 | Yes | |

| 2007 Jan | 29–38 | Min 14, max 34 | H5 | N3? | No | PQRETR GLF | |

| 2007 Mar | 35–38 | Punctual | H5 | ND¶ | No | ||

| 2007 Sep | 31–39 | Punctual | H6 | N5 | Yes | ||

| 2007 Dec | 27–37 | Min 42, max 56 | H9 | ND¶ | No | ||

| H1? | ND¶ | No | |||||

| H11? | ND¶ | No | |||||

| 2008 Feb/Mar |

30–38 |

Min 56, max 70 |

H9 |

ND¶ |

No |

|

|

| Isle of Koos, Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany | 2006 Dec | 29–35 | Min 14, max 28 | H4 | N6 | Yes | |

| 2007 Aug | 32–38 | Min 35, max 49 | H7 | N3 | Yes | PEIPKGR GLF |

*Radolfzell, Altenrhein, and Bregenz-Thal are located along Lake Constance. AIV, avian influenza virus; Ct, cycle threshold value; HA, hemagglutinin; NA, neuraminidase; min, minimum; max, maximum; ND, not determined. †Each sentinel flock comprised 10–20 birds. Only the initial detection of each AIV introduction and determined HA or NA subtypes are presented. ‡Results of matrix and nucleocapsid protein gene fragments by real-time reverse transcription–PCR. §AIV-positive, HA subtype not determined, non-H5, non-H7. ¶AIV-positive, NA subtype not determined, non-N1.

Table 2. Frequency of sentinel duck sampling and frequency of AIV detection at 5 locations in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria*.

| Sentinel location | Investigation period | No. samplings of sentinel flock† | No. AIV detections | AIV subtypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radolfzell, Germany | 2006 Oct–2008 Sep | 53 | 11 | H6N8, H2N5, H3N2, H3N8 |

| Altenrhein, Switzerland | 2007 Oct–2008 Sep | 24 | 7 | H2N2, H9N2, HxN2 |

| Bregenz-Thal, Austria | 2007 Feb–2008 Sep | 44 | 9 | H9N2, H3Nx, H1N1, H1Nx, LP H7Nx |

| Brandenburg, Germany | 2006 Oct–2008 May | 41 | 20 | H1?, LP H5Nx, H6N2, H6N5, H9Nx, H11? |

| Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany | 2006 Oct– 2008 Jun | 40 | 6 | H4N6, LP H7N3 |

*Radolfzell, Altenrhein, and Bregenz-Thal are located along Lake Constance. AIV, avian influenza virus; LP, low pathogenicity. †Each flock consisted of 10–20 birds.

Blood samples were collected from the ducks once a month, and serum was tested in a cNP-ELISA after heat inactivation at 56°C for 30 min. After each natural infection, sentinel animals seroconverted, and serum scored positive in the cNP-ELISA within 2–4 weeks. By hemagglutination inhibition test using homosubtypic but not autologous antigen, HA-specific antibodies were detected only rarely and at low titers.

Detection rates of AIV in sentinel ducks were compared with data from monitoring of healthy, trapped wild birds. From October 2006 through September 2008, a total of 1,953 wild birds were investigated for AIV within a radius of 30 km of Lake Constance, resulting in 47 (2.4%) AIV detections of subtypes H3Nx, LP H5N2, H6N8, LP H7Nx, H1N1, HxN1, H1Nx, and H9N2. During January 2007–May 2008, a total of 8 (0.4%) of 2,028 investigated wild bird samples from Brandenburg tested positive (subtypes H3N6, H6). In Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, 8,066 birds were tested; 23 (0.3%) AIV infections (subtypes H1Nx, LP H5N2, H6Nx, H12Nx, H16Nx) were found.

Conclusions

In practice, AIV surveillance of live wild birds is difficult and involves substantial labor and costs, particularly for purchase and maintenance of trapping equipment, salary of trapping staff, and laboratory analysis. Trapping of wild birds also can be biased by season and by bird species that are easier to catch. Low proportions of AIV-positive results (<3%) indicate the low cost:benefit ratio of surveillance based on trapping wild birds (2). In contrast, our findings demonstrate that the use of sentinel birds in regions with substantial wild bird populations achieves a high rate of AIV detection and, therefore, is an efficient supplement to active AIV monitoring. The detection of different AIVs among the sentinel ducks reflects the natural ecology of AIV at discrete locations. Recently, all duck species, especially dabbling ducks, have been assessed as high-risk species for possibly contributing to the transmission of HPAIV (H5N1) (15). Therefore, mallards as sentinel species ensure a high probability of detecting AIV if kept in direct contact with wild water birds. In addition, sites for sentinel stations need to be selected carefully to achieve spatial representation.

Although our study was conducted in areas where HPAIV (H5N1) had circulated in wild birds in 2006, this subtype was not found by screening live wild birds or by using sentinel birds during the study period. Therefore, persistent circulation of HPAIV (H5N1) in the wild bird populations is unlikely for the area of Lake Constance, the coastal area of Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, and the region of the Oder Valley in Brandenburg. However, because of the limited sample sizes, a low prevalence cannot be excluded. Although HPAIV (H5N1) was found only rarely in apparently healthy birds, e.g., in a pochard (Aythya ferina) in Switzerland in 2008 (Figure 1), regular testing of sentinel birds could increase the probability of detecting sporadic transmission of HPAIV in healthy wild water birds even in the absence of detectable deaths.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Food and Rural Areas in Baden-Württemberg; nature conservation and veterinary authorities in Baden-Württemberg, Brandenburg, and Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania; and veterinary authorities of the Canton Thurgau and St. Gallen in Switzerland for authorization of sentinel stations. We also thank the Nature Conservation Society Rheindelta, Austria. We appreciate the excellent assistance of J. Anklam and M. Calderana in sample processing and virus testing.

This work was supported by the project Constanze, grant no. 1.07.01 from the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office; the Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection, Germany (FSI, project no. 1-3.5); and the Federal Ministry of Health in Austria (BMGF-74600/0360-IV/6/2006).

Biography

Dr Globig is a veterinarian working with the International Animal Health team of the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute, Federal Research institute for Animal Health. Her main research interests are emerging infectious diseases and veterinary epidemiology.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Globig A, Baumer A, Revilla-Fernández S, Beer M, Wodak E, Fink M, et al. Ducks as sentinels for avian influenza in wild birds. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the internet] 2009 Oct [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/15/10/1633.htm

References

- 1.European Commission Decision 2004/111/EC of 23 July 2004. Implementation of surveys for avian influenza in poultry and wild birds in the Member States to be carried out during 2004. Official Journal of the European Union 2004;32(5.2).:20 [cited 2009 Jan 15]. Available from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2004:278:0059:0063:EN:PDF

- 2.Hesterberg U, Harris K, Moir R, Stroud D, Fabre C, Knight-Jones T, et al. Annual report on surveillance for avian influenza in wild birds in the EU during 2007. European Commission SANCO 2182/2008. [cited 2009 Jan 15]. Available from http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/diseases/controlmeasures/avian/annrepres_surv_wb_02-12-2006_en.pdf

- 3.Happold JR, Brunhart I, Schwermer H, Stärk KDC. Surveillance of H5 avian influenza virus in wild birds found dead. Avian Dis. 2008;52:100–5. 10.1637/8021-051407-Reg [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Globig A, Staubach C, Beer M, Koeppen U, Fiedler W, Nieburg M, et al. Epidemiological and ornithological aspects of outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 of Asian lineage in wild birds in Germany, 2006 and 2007. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2009;56:57–72. 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2008.01061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinnecker H, Sinnecker R, Zilske E, Köhler D. Detection of influenza A viruses and influenza epidemics in wild pelagic birds by sentinels and population studies. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg [A]. 1982;253:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starick E, Beer M, Hoffmann B, Staubach C, Werner O, Globig A, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus isolates from Germany in 2006 and 2007 suggest at least three separate introductions of H5N1 virus. Vet Microbiol. 2008;128:243–52. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann MA, Renzullo S, Baumer A. Phylogenetic characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses isolated in Switzerland in 2006. Virus Genes. 2008;37:407–13. 10.1007/s11262-008-0285-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2006/437/EC Commission Decision of 4 August 2006 approving a diagnostic manual for avian influenza as provided for in Council Directive 2005/94/EC. Official Journal of the European Union Legislation. 2006;237:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slomka MJ, Coward VJ, Bank J, Londt BZ, Brown IH, Voermans J, et al. Identification of sensitive and specific avian influenza polymerase chain reaction methods through blind ring trials organized in the European Union. Avian Dis. 2007;51(Suppl):227–34. 10.1637/7674-063006R1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spackman E, Senne DA, Myers TJ, Bulaga LL, Garber LP, Perdue ML, et al. Development of a real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for type A influenza virus and the avian H5 and H7 hemagglutinin subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3256–60. 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3256-3260.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster RG, Pérez DR. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch Virol. 2001;146:2275–89. 10.1007/s007050170002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gall A, Hoffmann B, Harder T, Grund C, Beer M. Universal primer set for amplification and sequencing of HA0 cleavage sites of all influenza A viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2561–7. 10.1128/JCM.00466-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phipps LP, Essen SC, Brown IH. Genetic subtyping of influenza A viruses using RT-PCR with a single set of primers based on conserved sequences within the HA2 coding region. J Virol Methods. 2004;122:119–22. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fereidouni SR, Starick E, Grund C, Globig A, Mettenleiter TC, Beer M, et al. Rapid molecular subtyping by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction of the neuraminidase gene of avian influenza A viruses. Vet Microbiol. 2009;135:253–60. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Commission Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health. SANCO 10268/2006. Rev.5. Guidelines on the implementation of survey programmes for avian Influenza in poultry and wild birds to be carried out in member states in 2007 [cited 2009 Jan 15]. Available from http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/diseases/controlmeasures/avian/surveillance4_en.pdf