1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease leading to dementia and eventually death. The disease is named after Alöis Alzheimer (German physician) who described the characteristic plaques and tangles in the brain of a 50 year old woman dying of the condition in 1906.1 There is no known cure for the disease. The only treatments are palliative.

AD was the 8th leading cause of death in 2000; accounting for 49,558 deaths in that year.2 It threatens to exact an increasing toll as life expectancy increases. Worldwide, the number of people with AD in 2006 was estimated to be 26.6 million. That number is projected to grow fourfold by 2050 (106.8 million people).3 In the U.S. the projection is as high as 4.58 million people with AD by 2047.4 Potential savings with disease delayed or averted are large. Brookmeyer et al estimate that an intervention resulting in a 1-year delay in disease onset would produce an annual savings of about 10 billion dollars 10 years after initiation of such an intervention.

These harsh realities have led various groups to mount randomized trials aimed at assessing the utility of various drugs and regimens in preventing development of the condition. One of those efforts culminated in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT).

ADAPT was an investigator-initiated, NIH-funded, primary prevention, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. It was designed to address the question of whether non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) could prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with the secondary objectives of determining whether the study treatments could attenuate cognitive decline associated with aging.

The drugs tested were celecoxib (Celebrex®, Pfizer) and naproxen sodium (Aleve®, Bayer).5 This paper describes design, methods, and baseline results of the trial. Particulars of the trial are given in Table 1. Table 2 gives a chronology of the trial.

Table 1.

ADAPT features and operating characteristics

| A. Profile |

| Descriptors: Randomized, multicenter, phase 4, double-masked, placebo-controlled, primary prevention, trial |

| Treatment structure: Simple (non factorial), parallel |

| Treatment groups: 3 (Celecoxib, naproxen, and matching placebos; see Section 3) |

| Funding source: National Institutes on Aging |

| Funding mode: Grant, cooperative agreement (U01 AG015477) |

| Disbursal of funds: Via contracts from the Study Chair's institution with participating centers |

| Centers: 8 |

| Field sites/clinics: 6 |

| Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ, Sch Med, Constantine Lyketsos, MD |

| Boston: Boston University, Sch Med, Robert Green, MD |

| Rochester (NY); Moore Community Hospital, M Saleem Ismail, MD |

| Seattle*: Univ Washington, Sch of Med, Suzanne Craft, PhD |

| Sun City (Az); Sun Health Research Institute, Marwan Sabbagh, MD |

| Tampa*: The Roskamp Institute Memory Clinic, Michael Mullan, MBBS, PhD |

| Coordinating Center (CC) (Baltimore) |

| Johns Hopkins University, Sch of Pub Health, Curtis Meinert, PhD |

| Office of Chair: Univ of Washington (Johns Hopkins Univ, Sch of Pub Health through 28 February 2002); John CS Breitner |

| Project Office (Bethesda) |

| National Institute on Aging, Neil Buckholtz, PhD |

| Start date: 1 March 2000 |

| Achieved sample size: 2,528 |

| B. Recruitment |

| Approach: Primarily via targeted mailings to selected zip code areas surrounding the field sites; mailing addresses provided by HCFA/CMS |

| Enrollment: 1st person randomized 8 March 2000 |

| Enrollment suspended: 17 Dec 200415 |

| No. randomized: 2,528 (see Figure 1) |

| C. Followup |

| Design: Common closing date for all regardless of when randomized (28 Feb 2007) |

| Person years of followup: 4,66015 |

| D. Randomization |

| Fixed assignment ratio: 1:1:1.5 (Cel:Nap:Plbo) |

| Stratification: Field site and age (3 age groups) |

| Assignment issued from CC after eligibility determined |

| E. Data collection/processing |

| Paper forms |

| Data entry at field sites via on-site PC |

| Data harvest done by CC; monthly |

| F. Sample size calculation |

| Outcome measure: AD incidence |

| Δ = 30% reduction in AD incidence |

| α = 0.05 (2-tailed) |

| 1 - β = Power = 0.80 for 30% reduction in AD incidence |

| Calculated sample size: 2,625 dementia-free subjects aged 72 – 88 with a history of Alzheimer-like dementia in a first degree relative |

| Assumed period of treatment and followup: 5 yr min; 7 yr max |

| Assumptions: 5%/yr loss to followup; Loss due to mortality: 4/100 in year 1, and an 8.5% /yr increase per yr thereafter; loss due to noncompliance to trt (ie, stop taking assigned trt and do not take an NSAID on a regular basis; 15% in 1st yr and 5%/yr thereafter); loss of precision due to use of NSAIDs in placebo-assigned participants (2.5%/yr) |

| G. Organizational bodies (September 2006) |

| Steering Committee (SC): 12; Study officers (SO) plus 6 field site directors |

| Study Officers (SO): 6; Study chair, chair of SC, director & deputy director of CC, field site director, & project officer |

| Research Group: ~50; SC, SO, field site coordinators, neuropsych-psychometricians, CC personnel |

| H. Treatment effects monitoring (TEMC) |

| Results by treatment group during trial seen only by the treatment effects monitoring committee |

| TEMC members: 5 voting, 3 nonvoting; voting members independent of ADAPT; appointed by study investigators with advice and consent of sponsor; nonvoting members: Director of CC, NIA Project Officers, study consultant |

| Meeting mode and frequency: Face-to-face, every six months; more frequent if necessary |

| Operating philosophy: Members not masked to treatment assignment; no adjustment for multiple looks; no preordained stopping rules |

Added November 2001

Table 2.

ADAPT chronology

| Event | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| D | E | |

| 2000 6 SC mtgs | ||

| Notice of grant award | 28 Feb | 2000 |

| 1st SC meeting; Sun City | 30 Mar | 2000 |

| Letter of agreement signed with Bayer | 7 Jun | 2000 |

| Contract with Health Care Financing Administration – HCFA (subsequently Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services – CMS) consummated for Medicare\Medicaid mailing list |

8 Aug | 2000 |

| Contract with ProClinical consummated for packaging and distribution of drug | 19 Oct | 2000 |

| Mailing list from HCFA received (1,343,722 records) | 25 Oct | 2000 |

| Training meeting (Baltimore) | 2–3 Nov | 2000 |

| Naproxen/matching placebo shipped to ProClinical by Bayer | 10 Nov | 2000 |

| Medicare beneficiary contact letter approved by CMS | 1 Dec | 2000 |

| Prototype phone screen & recruitment materials mailed to field sites | 01 Dec | 2000 |

| Letter of agreement signed with GD Searle/Pharmacia | 4 Dec | 2000 |

| Celecoxib/matching placebo shipped to ProClinical | 8 Dec | 2000 |

| 2001 5 SC mtgs, 2 SO mtgs, 2 TEMC mtgs, 4 site visits | ||

| Contract signed with McKesson BioServices Corp for blood draw kits and labels | 1 Feb | 2001 |

| Contract signed with Covance for laboratory determination | 14 Feb | 2001 |

| Drug shipped to field sites from ProClinical | 20 Feb | 2001 |

| Training meeting (Baltimore) | 22–23 Feb | 2001 |

| 1st Treatment Effects Monitoring Committee (TEMC) (conf call) | 27 Feb | 2001 |

| First participant randomized | 8 Mar | 2001 |

| SC conference call; vote on addition of Tampa and Seattle | 8 Nov | 2001 |

| 2002 4 SC mtgs, 6 SO mtgs, 2 TEMC mtgs, 5 site visits | ||

| Updated mailing list from CMS received (1,218,796 records) | 13 Feb | 2002 |

| Paper on ADAPT masking published5 | Feb | 2002 |

| Updated mailing list from CMS received (1,364,714 records) | 26 Apr | 2002 |

| Public Citizen letter to Sec'y of HHS requesting ADAPT be stopped45 | 4 Sep | 2002 |

| Letter from ADAPT to Sec'y HHS rebutting Public Citizen letter | 30 Sep | 2002 |

| NIH response to Public Citizen letter | 18 Nov | 2002 |

| 2003 2 SC mtgs, 5 SO mtgs, 2 TEMC mtgs, 7 site visits | ||

| Public Citizen letter to NIH re ADAPT46 | 13 Apr | 2003 |

| NIH response to Public Citizen letter | 13 May | 2003 |

| 2004 4 SC mtgs, 2 SO mtgs, 2 TEMC mtgs, 6 site visits | ||

| Competing renewal submission | 26 Feb | 2004 |

| SC vote to suspend treatment and enrollment (conf call) | 17 Dec | 2004 |

| NIH press conference re decision to suspend | 20 Dec | 2004 |

| FDA clinical hold issued | 23 Dec | 2004 |

| 2005 7 SC mtgs, 3 SO mtgs, 2 site visits | ||

| FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee meeting re celecoxib |

16–18 Feb | 2005 |

| Statement from ADAPT read at FDA hearing27 | 18 Feb | 2005 |

| SC vote to make trt suspension of 17 Dec permanent | 10 Mar | 2005 |

| NIA requests revision to competing renewal of 26 Feb 2004 | 18 Apr | 2005 |

| SC vote to lift results blackout; IND terminated; TEMC dissolved; ADAPT Advisory Committee created |

2 Aug | 2005 |

| SC & Research Group (RG) meeting; Seattle; outcome data presented by trt group | 6–7 Oct | 2005 |

| 2006 2 SC mtg, 14 SO mtgs, 6 site visits | ||

| Competing renewal resubmitted (application: 2 U01 AG015477–06A1) | 1 Mar | 2006 |

| ADAPT master data set available for distribution to field sites | 3 May | 2006 |

| Competing renewal reviewed by NIA study section | 12 Jul | 2006 |

| Summary statement (2 U01 AG015477–06A1; priority score: 172; 20.3 percentile) | Jul 28 | 2006 |

| ADAPT AD outcome manuscript submitted to Neurology | 22 Oct | 2006 |

| ADAPT CV and cerebrovascular safety results published15 | 17 Nov | 2006 |

| 2007 18 SO mtgs | ||

| Notification of closeout of data collection (PPM 93); 28 Feb 2007 | 3 Jan | 2007 |

| ADAPT AD outcome manuscript accepted for publication in Neurology14 | 22 Jan | 2007 |

| Treatment assignment unmasking (PPM 95) | 31 May | 2007 |

| Competing renewal resubmitted (application: 2 U01 AG015477–06A2) | 5 Jul | 2007 |

| ADAPT cognitive decline manuscript submitted to Archives of Neurology | 5 Jul | 2007 |

| On-site data entry discontinued (PPM 97) | 31 Aug | 2007 |

| Cessation of clinic funding (PPM 98) | 30 Sep | 2007 |

| Summary statement for 2 U01 AG015477–06A2 (priority score: 152; 15.1 %ile) | 12 Dec | 2007 |

| ADAPT cognitive decline manuscript accepted; Archives of Neurology | 13 Dec | 2007 |

| 2008 3 SO mtgs | ||

| Paper re lessons from ADAPT published8 | Jan | 2008 |

| Master data set distributed to ADAPT investigators | 20 Feb | 2008 |

2 Funding initiative

Efforts to fund the trial started with a grant application submitted to the NIH in May 1997 and culminated, two submissions later, in funding (Table 3). ADAPT was an investigator-initiated trial funded via a cooperative agreement with the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Table 3.

Initial funding history

| 1st submission |

| Study population: Cache County Utah cohort |

| Sample size: 3,100 |

| Treatments: Ibuprofen and matching placebo |

| Primary outcome measure: AD incidence |

| Enrollment period: 1 yr |

| Length of followup: 4 yrs |

| 5 yr budget: $10,486,428 |

| Submitted: 30 May 1997 |

| Outcome: Not funded; priority score: 263; percentile rank: 55.2 |

| 2nd submission |

| Study population: Cache County Utah cohort |

| Sample size: 2,800 |

| Treatments: Ibuprofen and matching placebo |

| Primary outcome measure: AD incidence |

| Enrollment period: 1yr |

| Length of followup: 4 yrs |

| 5 yr budget: $14,087,522 |

| Submitted: 13 February 1998 |

| Outcome: Not funded; priority score: 205; percentile rank: Not available |

| 3rd submission |

| Study population: 4 field sites (Bal, Bos, Roc, Logan) |

| Sample size: 2,625 |

| Treatments: Ibuprofen, celecoxib and matching placebos |

| Primary outcome measure: AD incidence |

| Enrollment period: 1.5 yrs |

| Length of followup: 7 yrs |

| 5 yr budget: $25,121,319 |

| Submitted: 1 March 1999 |

| Outcome: Funded; priority score: 166; percentile rank: 12.7 |

The original proposal was for a trial of ibuprofen and matching placebo. In response to suggestions from the Initial Review Group, the third submission was changed to compare ibuprofen and celecoxib to matching placebos.

The outcome measure remained constant as AD incidence. The period of time anticipated for enrollment increased from 12 months (first and second submissions) to 18 months in the funded proposal and the amount requested (5 yr totals) grew from $10,486,428 in the first submission to $25,121,319 in the funded proposal.

The approach to recruitment also changed. In the first submission recruitment was to take place in Cache County, Utah, building on work done there in another project that had characterized a cohort of nearly 5,000 elderly people.6,7 As the scope of the proposal was expanded, the approach changed to one involving four enrolling sites (one being in Cache County). Ultimately the Cache County site was dropped in favor of another site.

3 Choice of study treatments and treatment protocol

The study treatments and dosage schedules ultimately chosen are shown in Table 4. The criteria for stopping or interrupting treatment are given in Table 5.

Table 4.

ADAPT treatment regimens

| No. enrolled |

Treatment | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| 719 | Naproxen sodium; Nap (Aleve®, Bayer) |

220 mg b.i.d. (blue tablet/blue label) and placebo matched to celecoxib (white tablet/white label), given orally; 4 tablets / day |

| 726 | Celecoxib; Cel (Celebrex®, Pharmacia) |

200 mg b.i.d. (white tablet/white label) and placebo matched to naproxen (blue tablet/blue label), given orally; 4 tablets / day |

| 1,083 | Placebo (PLBO) | Placebo matched to naproxen (blue tablet/blue label) and placebo matched to celecoxib (white tablet/white label), given orally; 4 tablets / day |

Table 5.

Treatment protocol

| Criteria for study treatment termination |

| • The participant develops serious complications of an ulcer, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation, or obstruction (mandatory stop) |

| • Any condition that, in the opinion of the study physician, makes it medically inappropriate or risky for the participant to continue on study treatment |

| Criteria for study treatment interruption |

| • If the participant develops any signs or symptoms suggestive of an ulcer or kidney disease, the participant is withdrawn from study treatment pending an evaluation by the study physician and primary care physician (plus a specialist if necessary). The participant is put back on study treatment at the discretion of the study physician. |

| • If the participant develops an elevated blood pressure, creatinine, or potassium or a decreased hematocrit, he or she is referred for evaluation and treatment. The study physician determines whether it is medically necessary to interrupt study treatment. |

| • If the participant requires corticosteroids, or warfarin, ticlopidine or any type of anti- coagulant, study treatment is interrupted for the duration of usage. |

| • If the participant is taking ≥ 4 doses per week of any of the following, study treatment is interrupted: |

| - vitamin E (at doses > 600 IU per day) |

| - non-aspirin NSAIDs or aspirin (> 81 mg per day) |

| • The participant enrolls in any trial that is likely to interfere with ADAPT procedures or affect treatment outcomes |

| • If the participant develops any condition that in the opinion of the study physician makes it medically inappropriate or risky to continue treatment, study treatment is interrupted. |

The original plan was to test ibuprofen and celecoxib against a matching placebo. That plan was predicated on an assumption that it would be possible to obtain the drugs and matching placebos from the manufacturers. Funding was not adequate to cover purchase of the drugs or the manufacture of matching placebo. Several months of negotiations resulted in a commitment from Monsanto/Searle (manufacturers of Celebrex, later acquired by Pharmacia, and ultimately by Pfizer) to provide celecoxib in unmarked 200 mg “bright stock” capsules, and placebo capsules that were visually indistinguishable. It became clear early on, however, that the leading manufacturer of ibuprofen was not interested in supplying their drug and a placebo. Instead, they offered to supply commercially available drug for overencapsulation, suggesting that the large “overcapsules” could be filled with inert powder to make placebo. The investigators were concerned that the large capsules would be difficult to swallow, and also that they would be fairly easy to disassemble to see if they contained a recognizable dosage of the commercial agent. A consultant suggested that 220 mg naproxen sodium tablets (Aleve®) and matching placebo had been offered for other trials by Bayer, and that the company would probably make them available for ADAPT. Expert consultants saw no reason a priori that naproxen should not be substituted for ibuprofen. The notion of preparing and packaging 3 identical appearing capsules (celecoxib, naproxen, and placebo) was dismissed as being impractical because any change in packaging or formulation would have required extended testing and expense to satisfy the FDA regarding bio-availability and packaging.

4 Eligibility criteria

All trials represent select study populations. The requirement for informed consent alone renders them select, but they must also meet selection criteria. The eligibility and exclusion criteria for ADAPT are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| • Age 70 years or older at time of the eligibility evaluation visit |

| • Family history of one or more 1st degree relatives with Alzheimer-like dementia |

| • Collateral respondent available to provide information on cognitive status of study participant and to assist with monitoring of use of study medications, if necessary |

| • Sufficient fluency in written and spoken English to participate in study visits and neuropsychological testing |

| • Willingness to limit use of the following for the duration of treatment: |

| - vitamin E at doses > 600 IU/day |

| - non-aspirin NSAIDs or aspirin at doses > 81 mg/day |

| - histamine H2 receptor antagonists |

| - Ginkgo biloba extracts |

| • Intention and ability (in opinion of the study physician) to participate in regular study visits |

| • Consent |

| Exclusion criteria |

| • History of peptic ulcer complicated by perforation, hemorrhage, or obstruction |

| • History of peptic ulcer with symptoms within 4 weeks of intended enrollment date |

| • Concurrent use of warfarin, ticlopidine, or any other type of anti-coagulant |

| • Use of ≥ 4 doses/wk of any of the following in the 14 days prior to the intended enrollment date: |

| - histamine H2 receptor antagonists |

| - non-aspirin NSAIDs |

| - aspirin use > 81 mg/day |

| • Concurrent use of systemic corticosteroids |

| • Clinically significant hypertension, anemia, liver disease, or kidney disease (per guidelines in ADAPT Handbook) |

| • History of hypersensitivity or anaphylactoid response to sulfonamide antibiotics (eg, Bactrim, Septra, Gantrisin, Gantanol, Urobak), or to aspirin or other NSAIDs (eg, ibuprofen, dicofenac, celecoxib, naproxen) |

| • Plasma creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL |

| • Enrollment in any trial likely to interfere with ADAPT procedures or treatments |

| • Cognitive impairment or dementia according to criteria specified in ADAPT Neuropsychology Manual |

| • Current alcohol dependence or abuse |

| • Any condition that, in the opinion of the study physician, makes it medically inappropriate or risky for participant to enroll in ADAPT |

The approach to enrollment in ADAPT can be characterized as a "risk concentration design", i.e., one in which persons were screened to select those considered to be at increased risk for outcomes of interest.8 The efficiency of the design depends on the degree of risk concentration accomplished by the selection factors.

ADAPT attempted “risk concentration” for AD using two known risk factors, age and family history of dementia or AD. Clearly, the incidence of AD increases with age, so part of the debate had to do with where to set the lower age cutoff (there was no upper age cutoff in ADAPT). The higher the cutoff the higher the likely incidence, but the greater the difficulty in achieving the specified sample size. The grant application as submitted proposed a lower age cutoff of 72 years, but that was later lowered to 70 to increase the pool of potential recruits.

A family history of age-related dementia has been shown to be a risk factor for AD in various studies.9,10,11,12 Hence its use in ADAPT was as a screening variable to select people at increased risk.

Several of the exclusions (principally the first five proscriptions in the list of exclusions in Table 6) were imposed to reduce the risk of gastro-intestinal (GI) bleeds, inasmuch as conventional NSAIDs, including naproxen, carry known risks for such bleeding. Another obvious exclusion was use of " ≥ 4 doses/wk of non-aspirin NSAIDs" since such use might well be dangerous if in conjunction with naproxen or celecoxib. The exclusion basically had the effect of excluding people with arthritis or other conditions likely to render them as “obligate” NSAID users. Because arthritis is more common in women than men13 this exclusion, no doubt, biased the available pool toward men instead of women.

5 Outcome measures

Clearly, the choice of outcome measures is an important design decision in any trial. More often than not the so called primary outcome measure is also the design variable – the variable used in the sample size calculation. Investigators in ADAPT, from the outset, wanted a "clinically relevant" measure. The argument was between a measure of cognitive decline and actual diagnosis of AD. Ultimately they settled on AD even though it was obvious that the former would have produced a smaller sample size requirement. The concerns were, first, that the observational evidence base spoke much more strongly to a “protective” effect against AD dementia than to any such effect against cognitive decline. Second was a concern that the relevance of benefit in a less steep cognitive decline with age would be more difficult to translate into clinical relevance than measurable differences in AD incidence. But it was also clear that the trial would be strapped for power using AD unless it could follow large numbers of people for long periods of time – 7 years as the trial was designed. The availability of support for such a long time required an act of faith on the part of the investigators inasmuch as NIH grant funding is made available in five year intervals. A strong probability of re-funding was essential because, even if the trial succeeded in recruiting the large number of participants needed, there was little probability of demonstrating a difference with treatment – if indeed one existed at all – after the first funding cycle (2000 – 2005).

Having settled on AD as the primary outcome measure, with cognitive decline as a secondary outcome, the next problem was to develop a reasonable estimate of AD incidence in a placebo-assigned group of people aged 70 or over having a first degree relative with age-related dementia or AD. As is often the case in trials, especially in prevention trials, the investigators were forced to make an "educated guess" from published observational studies. The figures for AD incidence used were 2.5/100 for year 1; 2.75/100 for year 2; and 3.03/100 for year 3 but, as also is often the case, they proved to be overestimates.8 The observed incidence rate per 100 person years for all treatment groups combined was 0.7.14 Undoubtedly the low rate is reflective of a “healthy volunteer effect”, but it was almost certainly a consequence also of the eligibility criterion that participants have no detectable cognitive disorder at entry into the study.

6 Sample size specifications

The particulars for the sample size calculation underlying the trials are given in Panel F of Table 1. Relying on the assumptions stated in Table 1, the planned sample size was 2,625. Loss due to mortality was predicted at 4/100 in year 1 with an 8.5% annual increment thereafter. Probably as another reflection of the “healthy volunteer effect,” the actual observed mortality three year rate was only 1.27/100.15

7 Recruitment design

The primary difficulty in a prevention trial such as ADAPT lies in identification of people at risk of the disease of interest – AD. The usual approaches to recruitment common in trials, enrolling people already diagnosed with disease, do not work in primary prevention trials. People do not usually recognize themselves as being at risk for the disease or condition of interest. They have to be identified in some way. In ADAPT, the primary means of identification was by mass mailings to people aged 70 or over. The mailings were directed to eligible beneficiaries of Medicare using addresses supplied under an agreement between the NIA and HCFA (Health Care Financing Administration), renamed CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services).

The mailing lists comprised eligible Medicare beneficiaries who lived in areas around the field sites, as determined by zip code. All told, there were about 3.5 million mailings. This number includes 1.2 million re-mailings to people previously contacted in the initial waves of mailings. Use of the HCFA/CMS lists obligated investigators to initiate the mailing program with a letter on Government letterhead advising recipients that their names and addresses had been given to people running ADAPT, and stating explicitly that recipients were under no obligation to participate in the study (letter on ADAPT website, www.jhucct.com/adapt).

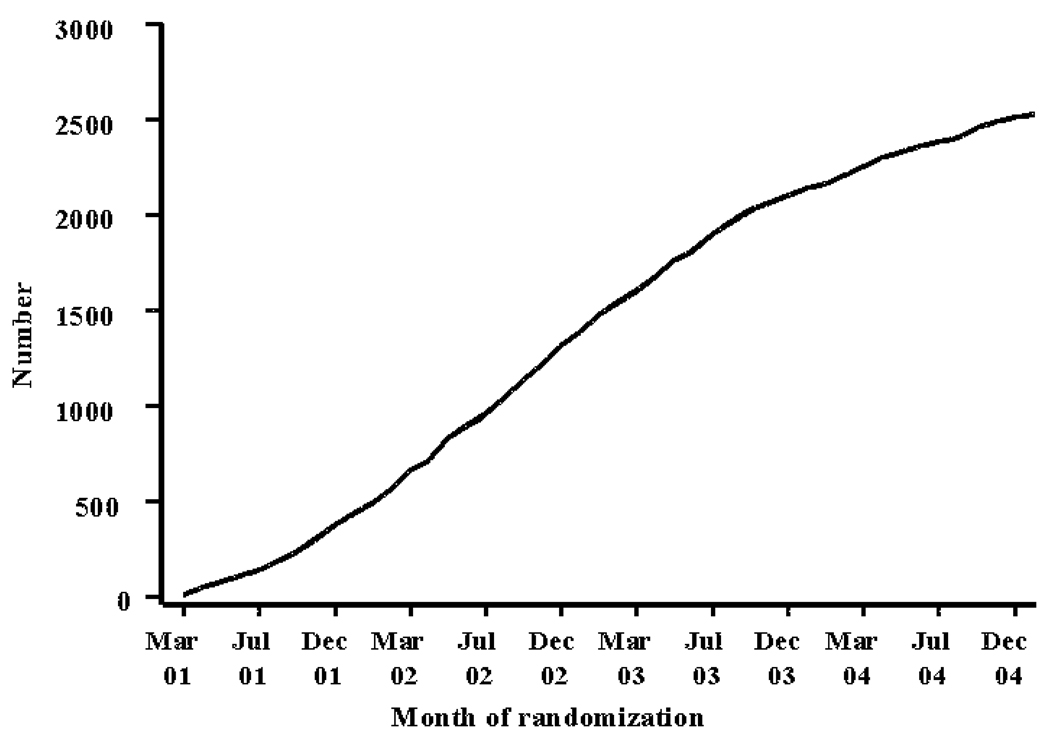

Mailings were done by a mailing service (Alliance Mass Mailing, Forest Hill, Maryland) in waves over the course of enrollment. The general approach was to start with a mailing to a few thousand people per field site and then increase the number as field sites became proficient at screening and enrollment. The first mailings occurred in late April 2001 and the last ones in early December 2004. See Figure 1 for enrollment over time.

Figure 1.

Enrollment over time

The yield from these mailings ranged in the neighborhood of 0.8 per 1,000 mailings and around half that fraction for re-mailing to previous recipients of letters.

The vast number of people enrolled came from the HCFA/CMS mailings. Less than 5% came via other means including (depending on the field site), use of voter registration lists, local newspaper and radio ads, presentations to church groups and civic organizations, and presentations at area academic institutions, hospitals and nursing homes.

See the ADAPT website (www.jhucct.com/adapt) for prototype copies of consent forms.

8 Randomization, masking, followup, and data collection designs

Randomization was controlled by the coordinating center. Field sites requested assignment after keying essential data necessary for assignment plus data to determine eligibility and absence of excluding conditions. Randomization was in permuted blocks of sizes 7 or 14 arranged (randomly ordered) within three age strata − 70–74, 75–79, and 80+ − within field site. Participants were counted as enrolled in the treatment group to which assigned on release of the assignment to a field site.

Treatments were administered in double-masked fashion. Masking was accomplished by use of placebos matching the celecoxib and naproxen treatments. See Martin et al5 for details on the masking. People removed from treatment by study personnel during the trial remained masked to assignment. The mask for participants and study personnel remained in place until June 2007 when it was lifted via mailings to study participants revealing assignment.

Followup was independent of treatment, that is, all persons were followed via regular study visits and telephone contacts even if they were no longer adherent to the assigned study treatment. All persons were followed to a common closing date, 28 February 2007.

The data collection schedule is outlined in Table 7. Data collection was via paper forms keyed by study personnel at the field sites via dedicated PCs. Harvests of data were done monthly by coordinating center personnel.

Table 7.

Data collection schedule

| EL* visit− 1 |

EN* visit 0 |

Followup contacts (mos from EN visit) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 24… | |||

| Type of visit/contact | |||||||||||

| Eligibility | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Enrollment | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Cognitive assessment | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Interval | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Telephone | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Procedures | |||||||||||

| Consent | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Physical exam | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Med history | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Neurological exam | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Laboratory tests | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Blood sample | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Review of compliance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Review of med use | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Review of adverse events | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Dispensing study drug | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Neuropsychological tests | |||||||||||

| Modified Mini-Mental | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Digit span | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Generative Verbal Fluency | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rivermead Memory Test | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hopkins Verbal Learning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Visuospatial Memory Test | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Self-rating Memory Functions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Geriatric Depression Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dementia Severity Rating | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

EL = eligibility; EN = enrollment

The list of study instruments used in ADAPT is given in Table 8.

Table 8.

Data collection instruments

| Neuropsychological tests |

| Modified Mini-Mental State Examination-Epidemiological (3MS-E) [Teng & Chui, 1987]28 |

| Digit Span [Wechsler, 1981]29 |

| Generative Verbal Fluency |

| Narratives from the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test [Wilson et al, 1989]30 |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - Revised (HVLT-R) [Brandt, 1991]31 |

| Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised [Benedict, 1996]32 |

| Self-rating of Memory Functions (self-administered) [Squire et al, 1979]33 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (self-administered) [Yesavage et al, 1983]34 |

| Dementia evaluation battery |

| Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) battery [Morris et al, 1989]35 |

| Trail Making Test [Reitan, 1986]36 |

| Logical Memory [Wechsler, 1987]37 |

| Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) [Benton, 1974]38 |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWA) [Benton, 1988]39 |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) [Smith, 1982]40 |

| Shipley Vocabulary [Zachary, 1991]41 |

| Self-Rating of Memory Functions [Squire et al, 1979]33 |

| Collateral respondent questionnaires |

| Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS) (self-administered) [Clark & Ewbank, 1996]42 |

| Dementia Questionnaire (DQ-cr) [Silverman et al, 1986]43 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [Cummings et al, 1994]44 |

9 Baseline data

Table 9 provides a description of the study population as enrolled. Data summarized in the table were collected during the eligibility and enrollment visits (see Table 7 for data collection schedule). The median age at entry was 74. Ages at enrollment ranged from 70 – 90.

Table 9.

Baseline results

| Total |

Cel |

Nap |

Plbo |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | p | |

| Randomized | 2,528 | 726 | 719 | 1,083 | |||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 70–74 | 1,402 | 55.5 | 402 | 55.4 | 401 | 55.8 | 599 | 55.3 | |

| 75–79 | 796 | 31.5 | 228 | 31.4 | 228 | 31.7 | 340 | 31.4 | |

| 80–84 | 286 | 11.3 | 84 | 11.6 | 76 | 10.6 | 126 | 11.6 | |

| > 85 | 44 | 1.7 | 12 | 1.7 | 14 | 1.9 | 18 | 1.7 | |

| 2,528 | 100.0 | 726 | 100.1 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | ||

| Gender | 0.69 | ||||||||

| Male | 1,368 | 54.1 | 384 | 52.9 | 389 | 54.1 | 595 | 54.9 | |

| Female | 1,160 | 45.9 | 342 | 47.1 | 330 | 45.9 | 488 | 45.1 | |

| 2,528 | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | ||

| Race/ethnic origin | 0.06 | ||||||||

| White | 2,451 | 97.0 | 698 | 96.1 | 698 | 97.1 | 1,055 | 97.4 | |

| African-American | 44 | 1.7 | 15 | 2.1 | 16 | 2.2 | 13 | 1.2 | |

| Hispanic | 18 | 0.7 | 10 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.6 | |

| Other | 15 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.8 | |

| 2,528 | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | ||

| Education | 0.21 | ||||||||

| < High school | 102 | 4.0 | 28 | 3.9 | 35 | 4.9 | 39 | 3.6 | |

| HS graduate | 503 | 19.9 | 151 | 20.8 | 126 | 17.5 | 226 | 20.9 | |

| Some college | 695 | 27.5 | 201 | 27.7 | 204 | 28.4 | 290 | 26.8 | |

| College degree | 484 | 19.1 | 139 | 19.1 | 122 | 17.0 | 223 | 20.6 | |

| Post-graduate ed | 744 | 29.4 | 207 | 28.5 | 232 | 32.3 | 305 | 28.2 | |

| Marital status | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Married | 1,817 | 71.9 | 510 | 70.2 | 539 | 75.0 | 768 | 70.9 | |

| Widowed | 461 | 18.2 | 143 | 19.7 | 116 | 16.1 | 202 | 18.7 | |

| Separated | 13 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.3 | 8 | 0.7 | |

| Divorced | 171 | 6.8 | 50 | 6.9 | 42 | 5.8 | 79 | 7.3 | |

| Never married | 65 | 2.6 | 20 | 2.8 | 20 | 2.8 | 25 | 2.3 | |

| Not reported | 1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Alcohol drinks/wk | 0.89 | ||||||||

| 0 | 919 | 36.4 | 266 | 36.6 | 258 | 35.9 | 395 | 36.5 | |

| 1–6 | 901 | 35.6 | 261 | 36.0 | 257 | 35.7 | 383 | 35.4 | |

| 7–12 | 457 | 18.1 | 132 | 18.2 | 137 | 19.1 | 188 | 17.4 | |

| 13–21 | 251 | 9.9 | 67 | 9.2 | 67 | 9.3 | 117 | 10.8 | |

| Hx smoking | 0.07 | ||||||||

| Never | 1,123 | 44.4 | 337 | 46.4 | 338 | 47.0 | 448 | 41.4 | |

| Past | 1,331 | 52.7 | 364 | 50.1 | 362 | 50.4 | 605 | 55.9 | |

| Current | 74 | 2.9 | 25 | 3.4 | 19 | 2.6 | 30 | 2.8 | |

| Hx peptic ulcer | 0.97 | ||||||||

| Yes | 112 | 4.4 | 32 | 4.4 | 33 | 4.6 | 47 | 4.3 | |

| No | 2,416 | 95.6 | 694 | 95.6 | 686 | 95.4 | 1,036 | 95.7 | |

| Hx stroke | 0.54 | ||||||||

| Yes | 29 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.5 | 7 | 1.0 | 11 | 1.0 | |

| No | 2,499 | 98.9 | 715 | 98.5 | 712 | 99.0 | 1,072 | 99.0 | |

| Hx transient ischemia | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | 0.64 | |

| Yes | 88 | 3.5 | 23 | 3.2 | 23 | 3.2 | 42 | 3.9 | |

| No | 2,440 | 96.5 | 703 | 96.8 | 696 | 96.8 | 1,041 | 96.1 | |

| Hx coronary artery bypass | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | 0.82 | |

| Yes | 106 | 4.2 | 29 | 4.0 | 33 | 4.6 | 44 | 4.1 | |

| No | 2,422 | 95.8 | 697 | 96.0 | 686 | 95.4 | 1,039 | 95.9 | |

| Hx angina | 0.83 | ||||||||

| Yes | 110 | 4.4 | 34 | 4.7 | 29 | 4.0 | 47 | 4.3 | |

| No | 2,418 | 95.6 | 692 | 95.3 | 690 | 96.0 | 1,036 | 95.7 | |

| Hx congestive heart disease | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | 0.22 | |

| Yes | 22 | 0.9 | 10 | 1.4 | 5 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.6 | |

| No | 2,506 | 99.1 | 716 | 98.6 | 714 | 99.3 | 1,076 | 99.4 | |

| Hx myocardial infarction | 0.12 | ||||||||

| Yes | 130 | 5.1 | 39 | 5.4 | 27 | 3.8 | 64 | 5.9 | |

| No | 2,398 | 94.9 | 687 | 94.6 | 692 | 96.2 | 1,019 | 94.1 | |

| Hx emphysema or COPD | 0.27 | ||||||||

| Yes | 86 | 3.4 | 23 | 3.2 | 31 | 4.3 | 32 | 3.0 | |

| No | 2,442 | 96.6 | 703 | 96.8 | 688 | 95.7 | 1,051 | 97.0 | |

| Hx osteoarthritis | 2,528 | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | 0.61 |

| Yes | 751 | 29.7 | 209 | 28.8 | 209 | 29.1 | 333 | 30.7 | |

| No | 1,777 | 70.3 | 517 | 71.2 | 510 | 70.9 | 750 | 69.3 | |

| Hx rheumatoid arthritis | 2,528 | 100.0 | 726 | 100.0 | 719 | 100.0 | 1,083 | 100.0 | 0.59 |

| Yes | 50 | 2.0 | 16 | 2.2 | 11 | 1.5 | 23 | 2.1 | |

| No | 2,478 | 98.0 | 710 | 97.8 | 708 | 98.5 | 1,060 | 97.9 | |

| Hx other non-aspirin NSAID (any dose) or aspirin (>81mg/day) | 0.72 | ||||||||

| Yes | 435 | 17.2 | 121 | 16.7 | 120 | 16.7 | 194 | 17.9 | |

| No | 2,093 | 82.8 | 605 | 83.3 | 599 | 83.3 | 889 | 82.1 | |

| Histamine H2-receptor use | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Yes | 64 | 2.5 | 11 | 1.5 | 25 | 3.5 | 28 | 2.6 | |

| No | 2,464 | 97.5 | 715 | 98.5 | 694 | 96.5 | 1,055 | 97.4 | |

The gender mix was 54:46 male to female. The corresponding mix in the U.S. (2000 Census data) is 39:61. The under-representation of women relative to their numbers in the general population is likely the result of the exclusion of people requiring regular treatment for the pain of arthritis – a condition more common in women than men.13

The population enrolled was predominantly white (97%) in spite of efforts to recruit minorities.

Over 3/4ths of the enrolled population had some college education with over 40% having earned a college degree – roughly twice the percentages in the corresponding U.S. population for people aged 70 −74.16

Nearly 3/4ths of the population enrolled were married on entry. About 7% reported being divorced, about the same as for similarly aged people in the U.S. population (http://www.census.gov/acs/www/; accessed 31 March 2008).

About 70% of the enrolled population consumed 6 or fewer drinks per week.

Less than 3% were cigarette smokers on entry. The corresponding figures for the U.S. population for people aged 65 and over was 8.3% as per the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2007 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/200712_08.pdf; accessed 31 March 2008). Forty-four percent reported never having smoked cigarettes.

About 17% of the enrollees reported having used non-aspirin NSAID (any dose) or aspirin (>81mg/day) aspirin in the past.

10 Postscripts

The impetus for ADAPT was driven by observational data suggesting that use of NSAIDs may reduce the incidence of AD and age-related dementia.17 By the time the trial was funded, NSAIDs capable of inhibiting activity of the COX-2 enzyme – an enzyme responsible for pain and inflammation – were available18 (NDA application 20–998; FDA approval 31 December 1998; http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/98/20998AP_appltr.pdf; accessed 31 Mar 2008). As is often the case, the newest drug is the one viewed as having the most promise. The promise in this case came from the hope that this class of drugs would have less GI toxicity than non-selective COX-2 NSAIDs. That promise is what ultimately led investigators to include a member of that class in ADAPT – celecoxib. But that decision was also the source of difficulties in ADAPT. These difficulties started in September of 2002 with a petition to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) that ADAPT be stopped because of generic concerns regarding the safety and adequacy of celecoxib. That petition was ultimately rejected, but concerns regarding the safety of the COX-2 inhibiting drugs were raised anew when Merck decided to withdraw another COX-2 inhibitor, rofecoxib (Vioxx®) from the market in September of 2004 because of newly revealed cardiovascular risks. That decision prompted the need for a letter to participants in ADAPT informing them of the withdrawal and that one of the drugs in ADAPT was a member of the COX-2 inhibiting class of drugs. The ADAPT Treatment Effects Monitoring Committee (TEMC) routinely reviewed both safety and efficacy data at its regular meetings, including its meeting of 10 December 2004. On all occasions the TEMC recommended continuation of the trial without modification. The recommendation made on 10 December was based on data gathered through 1 October 2004, but it was also clear that they saw little prospect for continuing much beyond its spring meeting unless signs of benefit started to appear.

Seven days after the meeting, on the morning of Friday 17 December a Study Officer (Director of the Coordinating Center) was informed by telephone by a representative of Pfizer, the supplier of celecoxib for ADAPT, that it was going to announce later that day that a placebo-controlled trial of celecoxib for prevention of colon polyps was being stopped because excess cardiovascular risk in the celecoxib-treated group.19 That information was relayed by the director of the ADAPT coordinating center to the ADAPT steering committee later that day in a conference call. It was during that conference call that the investigators voted to suspend treatments pending further review. The option of suspending the celecoxib treatment and continuing the naproxen treatment and its placebo was considered but rejected, since doing so would have required unmasking treatment assignments. As it turned out, even if the investigators had decided to continue the treatments, they would have been ordered six days later to suspend them when the FDA issued clinical holds on all Celebrex prevention trials (www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2004/ANS01336.html; accessed 3 April 2008; investigators notified of hold by phone 23 December 2004; see ADAPT website for letter; www.jhucct.com/adapt). The hold for ADAPT was to remain in effect until the FDA was satisfied with revision of the investigator brochure and consent documents, re-consent procedures for people already enrolled, and revision of the protocol to "ensure adequate monitoring and assessment of cardiovascular events across treatment arms".

ADAPT policy was to publish results leading to any major protocol change. Hence, once investigators voted to make the suspension permanent (see Table 2 for dates), they set about preparing a paper summarizing the cardiovascular data accumulated in ADAPT. As it turned out, it would take repeated tries with various journals before results were published (see Table 10). The reasons for rejection were that the differences, though in the wrong direction, were not "statistically significant" and hence not "believable", that the results were based on raw counts without independent reading, and that the results were somehow tainted because the decision to stop was not the product of a formal recommendation from the ADAPT TEMC. Some of these issues are raised in an accompanying commentary to the ADAPT publication by Nissen and in a reply to those comments by ADAPT investigators.20,21

Table 10.

Efforts to publish ADAPT cardiovascular and cerebrovascular data

| Event | Date | |

|---|---|---|

| D | E | |

| Study treatment suspended | 17 Dec | 2004 |

| Treatment suspension made permanent | 31 Mar | 2005 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to New Engl J Med | 5 May | 2005 |

| Rejection by New Engl J Med | 25 May | 2005 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to JAMA | 13 Oct | 2005 |

| Rejection by JAMA | 9 Nov | 2005 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to Arch Int Med | 21 Nov | 2005 |

| Rejection by Arch Int Med | 1 Dec | 2005 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to Lancet | 22 Dec | 2005 |

| Request for revisions from Lancet | 16 Jan | 2006 |

| Submission of revised manuscript to Lancet | 2 Feb | 2006 |

| Rejection by Lancet | 20 Mar | 2006 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to BMJ | 30 Apr | 2006 |

| Rejection by BMJ | 18 May | 2006 |

| Submission of safety manuscript to PloS Clinical Trials | 25 Jun | 2006 |

| Request for revisions from PLoS Clinical Trials | 25 Jul | 2006 |

| Publication of Salpeter et al meta-analysis22 | Jul | 2006 |

| Submission of revised manuscript to PloS Clinical Trials | 15 Aug | 2006 |

| Second request for revisions from PLoS Clinical Trials | 5 Sep | 2006 |

| Submission of second revision to PLoS Clinical Trials | 11 Sep | 2006 |

| Acceptance of safety manuscript by PLoS Clinical Trials | 29 Sep | 2006 |

Interestingly, results from ADAPT along with results from several other studies were published in 2006 prior to our own publication in a paper by Salpeter et al.22,23,24,25

A meta-analysis involving cardiovascular safety data from ADAPT and five other celecoxib-placebo controlled trials was published in early 2008.26

Acknowledgments

The writing committee extends special thanks to Jane Anau of the Office of the Chair and to Alka Ahuja, Huibo Shao, and Anne Shanklin of the Coordinating Center.

ADAPT was funded by the NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA) via a cooperative agreement; grant no. U01 AG15477

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Curtis L Meinert, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, The Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 615 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore Maryland 21205.

Lee D McCaffrey, Sr Research Associate, The Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 615 North Wolfe Street, Baltimore Maryland 21205.

John CS Breitner, Professor and Head, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Director, GRECC (S-182), VA Puget Sound Health Care System, 1660 South Columbian Way, Seattle, WA 98108.

References

- 1.Alzheimer A. Jarvik L, Greenson H, translators. About a peculiar disease of the cerebral cortex. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1987;1:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson RN. Deaths: Leading causes for 2000. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002;50:1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Pub Health. 1998;88:1,337–1,342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin KM, Meinert CL. Breitner JCS for the ADAPT Research Group: Double placebo design in a prevention trial for Alzheimer's disease. Controlled Clin Trials. 2002;23:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tschanz JT, Corcoran C, Skoog I, Khachaturian AS, Herrick KM, Hayden KLM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Calvert T, Norton MC, Zandi P, Breitner JC. Cache County Study Group: Dementia: The leading predictor of death after age 85. The Cache County Study. Neurology. 2004;62:1,156–1,162. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118210.12660.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tschanz JT, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, Corcoran C, Green RC, Hayden K, Norton MC, Zandi PP, Toone L, West NA, Breitner JCS, and the Cache County Investigators Conversion to dementia from mild cognitive disorder: The Cache County Study. Neurology. 2006;67:229–234. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000224748.48011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meinert C, Brietner JCS. Chronic disease long-term drug prevention trial: Lessons from the Alzheimer's Disease Anti-inflammatory Trial (ADAPT) Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2008;4:S7–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman JM, Smith CJ, Marin DB, Mohs RC, Propper CB. Familial patterns of risk in very late-onset Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:190–197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman JM, Li G, Zaccario ML, Smith CJ, Schmeidler J, Mohs RC, Davis KL. Patterns of risk in first-degree relatives of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:317–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070069012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince M, Cullen M, Mann A. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and dementia: A case-control study based on the MRC elderly hypertension trial. Neurology. 1994;44:97–104. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Duijn CM, Clayton D, Chandra V, Fratiglioni L, Graves AB, Heyman A, Jorm AF, Kokmen E, Kondo K, Mortimer JA, Rocca WA, Shalat, Soininen H. Hofman A for the Eurodem Risk Factor Research Group: Familial aggregation of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders: A collaborative re-analysis of case-control studies. EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20 Suppl 2:S13–S20. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.supplement_2.s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theis KA, Helmick CG, Hootman JM. Arthritis burden and impact are greater among U.S. women than men: Intervention opportunities. J Women's Health. 2007;16:441–453. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ADAPT Research Group. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:1,800–1,808. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260269.93245.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ADAPT Research Group. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular results from the randomized, controlled Alzheimer's Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT) PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(7):e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010033. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoops N. Current Population Reports. US Census Bureau; 2004. Educational attainment in the United States: 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman R, Kawas C. The epidemiology of dementia and Alzheimer disease. In: Terry RD, Katzman R, Bick KL, editors. Alzheimer Disease. New York: Raven Press, Ltd; 1994. pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masferrer JL, Seibert K, Zweifel B, Needleman P. Endogenous glucocorticoids regulate an inducible cyclooxygenase enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:3,917–3,921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, Anderson WF, Zauber A, Hawk E, Bertognolli M, for the Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) Study Investigators Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. NEJM. 2005;352:1,071–1,080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nissen SE. The wrong way to stop a clinical trial. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010035. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitner JCS, Martin BK, Meinert CL. The suspension of treatments in ADAPT: Concerns beyond the cardiovascular safety of celecoxib or naproxen. PLoS Clin Trials. 2006;1(8):e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0010041. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salpeter SR, Gregor P, Ormiston TM, Whitlock R, Raina P, Thabane L, Topol EJ. Meta-Analysis: Cardiovascular events associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 2006;119:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breitner JCS, Evans D, Lyketsos C, Martin B, Meinert C. ADAPT Trial Data. Am J Med. 2007;120:e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.022. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salpeter SR, Topol EJ. Letter; The reply. Am J Med. 2007;120:e5. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alpert JS. Editor's note re policy requiring written permission from individuals or groups generating data used in a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2006;120:e7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon SD, Wittes J, Finn PV, Fowler R, Viner J, Bertagnolli MM, Arber N, Levin B, Meinert CL, Martin B, Pater JL, Goss PE, Lance P, Obara S, Chew EY, Kim J, Arndt G, Hawk E, for the Cross Trial Safety Assessment Group Cardiovascular risk of celecoxib in 6 randomized placebo-controlled trials: The Cross Trial Safety Analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:2,104–2,113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.764530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ADAPT Steering Committee. Statement for the FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee (read by C Lyketsos) 2005 February 18; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J of Clinical Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised, Manual. New York: Psychological Corp; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson B, Cockburn J, Baddeley A, Hiorns R. The development and validation of a test battery for detecting and monitoring everyday memory problems. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11:855–870. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: development of a new verbal memory test with six equivalent forms. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benedict RH, Schrectlen D, Groninger L, Dobrashi M, Shpritz B. Revision of the Brief Visuospatial Memory Tests: studies of normal performance, reliability and validity. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Squire LR, Wetzel CD, Slater PC. Memory complaint after electroconvulsive therapy: Assessment with a new self-rating instrument. Biol Psychiatry. 1979;14:791–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatric Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1,159–1,165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reitan RM. Trail Making Test: Manual for Administration and Scoring. Tucson: Reitan Neuropsychological Laboratory; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised Manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benton A. Revised Visual Retention Test. 4th ed. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benton A, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test—manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zachary RA. Shipley Institute of Living Scale—Revised manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark CM, Ewbank DC. Performance of the Dementia Severity Rating Scale: A caregiver questionnaire for rating severity in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1986;10:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman JM, Breitner JCS, Mohs RC, Davis KL. Reliability of the family history method in genetic studies of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1,279–1,282. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.10.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2,308–2,314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barehenn E, Lurie P, Wolfe SN. Letter to HHS Secretary Tommy Thompson that raises ethical concerns about the “Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial” (ADAPT) (HRG Publication #1637) 2002 September 4; www.citzen.org/publication/release.cfm?ID=7195.

- 46.Barbehenn E, Lurie P, Wolfe SN. [(accessed 27 March 2008)];Letter to NIH Director that continues to raise ethical concerns about the “Alzheimer's Disease Anti-Inflammatory Prevention Trial” (ADAPT) (HRG Publication #1663) 2003 April 13; [Google Scholar]