Abstract

Background

Co-learning is one of the core principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Often, it is difficult to engage community members beyond those involved in the formal partnership in co-learning processes. However, to understand and address locally relevant root factors of health, it is essential to engage the broader community in participatory dialogues around these factors.

Objective

This article provides a glimpse into how using a photo-elicitation process allowed a community–academic partnership to engage community members in a participatory dialogue about root factors influencing health. The article details the decision to use photo-elicitation and describes the photo-elicitation method.

Method

Similar to a focus group process, photo-elicitation uses photographs and questions to prompt reflection and dialogue. Used in conjunction with an economic development framework, this method allows participants to discuss underlying, or root, community processes and structures that influence health.

Conclusion

Photo-elicitation is one way to engage community members in a participatory dialogue that stimulates action around root factors of health. To use this method successfully within a CBPR approach, it is important to build on existing relationships of trust among community and academic partners and create opportunities for community partners to determine the issues for discussion.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, qualitative research, social determinants of health, community health partnerships

A focal point in public health is the presence of disease and its distribution across populations. Public health researchers are adept at designing interventions to prevent and address the state of disease. However, researchers are less likely to identify and design strategies that address underlying root factors, or social determinants, of health. Public health efforts in Pemiscot County, Missouri, reflect this tension. In the 1990s, the Pemiscot County Heart Health Coalition was formed to address the high rate of heart disease among African Americans in the county.1 Community members in Pemiscot County and researchers from Saint Louis University worked together to develop and implement programs and policies aimed at reducing heart disease risk. Mainly, the partnership focused on programs and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. These efforts were successful for some; however, others in the community, specifically African-American men, did not benefit from the programs and policies created.

Acknowledging that a new approach was necessary, the partnership began to shift from researcher-led efforts to a CBPR approach. CBPR principles are asset focused and build on the ideals of equitable participation, mutual benefit, co-learning, capacity building, empowerment, sustainability, and balance between research and action.2–4 A CBPR approach allows the research question and direction to develop organically from dialogue between community members and researchers.2 The community–academic partnership in Pemiscot County saw CBPR, with a reliance on these principles and rooted in partnership, as an optimal way to engage those not benefiting from traditional health education programs and progress toward innovative solutions to address the root factors of health.

Through the work of the Heart Health Coalition, the community was aware of the high rates of heart disease and related behavioral risk factors. Yet, to date, there had been no discussion of the non-behavioral factors that contribute to heart disease and poor health. The first step in moving toward a CBPR approach involved asking community members associated with the Pemiscot County Heart Health Coalition to identify factors related to community health. Community members identified absence of educational and economic opportunities, particularly for men, as root causes of chronic diseases for African Americans in the county. The community members noted that Pemiscot County, a rural community in southeast Missouri, is isolated from large urban centers that offer more job opportunities. In this context, African-American men in Pemiscot County struggle to identify and secure education, training, and employment opportunities. This reflection explained, in part, why traditional health education programs were not benefiting African-American men.

The community members’ perception that education and employment are linked to health is supported by empirical evidence. It is estimated that social circumstance (e.g., education, income, employment) and environmental conditions account for approximately 20% of deaths in the United States,5,6 and the other 80% is due to a combination of genetics, medical care, and behavior (e.g., physical activity, alcohol consumption). Research shows that both lower educational attainment and unemployment status independently contribute to premature mortality7–14 and that each may also indirectly affect health outcomes. For example, education helps one to develop critical thinking and decision-making skills that increase one’s capacity to make better health decisions and adapt to medical advances.15 Meanwhile, unemployment is associated with poverty, psychological distress, and/or unhealthy behaviors like smoking or increased alcohol consumption.11–17 In addition, education and employment act synergistically. Often, education is the gatekeeper for employment. Higher educational attainment increases access to safer, more stable employment and higher paying jobs.18

Identification of limited access to education and employment opportunities, particularly for African-American men, led the partnership to develop a project called Men on the Move (MOTM). As an offspring of the Heart Health Coalition, MOTM was formed to understand how limited educational and employment opportunities influence community health. The goal of MOTM was to develop programs and policies that enhance educational and employment opportunities for African-American men in Pemiscot County and build the foundation for improved community health.

Committed to the principles of CBPR, MOTM began the planning process with reflection and co-learning. The MOTM partners determined issues and ideas to be discussed to plan an appropriate intervention for the men. The partnership chose readings about education, employment, experiences of black men, and health disparities. For example, a chapter from Bell Hooks’ Black Men and Masculinity19 was read in combination with an editorial by Sherman James on health disparities.20 Community and academic partners had a few weeks to read the materials and reflect on three questions: (1) What was your general impression of the readings? (2) Did the author raise points that relate to the situation in Pemiscot County? (3) Did you disagree with any ideas the author raised in the readings? After reading and reflecting, the partnership discussed the readings, shared reflections, and considered how the readings could contribute to intervention development.

The MOTM partners used the ideas of Paulo Freire to develop their co-learning process. Freire, an educator, believed that communities are able to name problems and identify solutions through participatory dialogue.21,22 Participatory dialogue is more than discussion. It is a process of reflection, dialogue, and action that aids communities in change. To prompt this type of dialogue, Freire often used triggers.23 The readings MOTM partners used are one example of a trigger. Other triggers have been used in public health as well. For example, in photovoice, photographs taken by participants have been used as triggers to stimulate dialogue around issue identification and community assessment.24 Stories circles are another example. Stories circles use narratives to trigger dialogue around program planning and community development.25

The MOTM partnership found participatory dialogue prompted by a trigger productive. The partnership identified the need to engage community members beyond those involved in the partnership in a similar dialogue process. The MOTM partners chose the photo-elicitation method to engage community members in a dialogue about the factors affecting access to opportunities for education and employment in Pemiscot County. Photo-elicitation is similar to a focus group but uses photographs, taken by someone outside the community, in addition to questions to trigger dialogue.26

The MOTM partnership chose photo-elicitation for three reasons. First, unlike literary triggers used previously by the MOTM partnership, photo-elicitation opens the participatory dialogue process to those with low literacy.27 Second, MOTM wanted to focus on institutional and collective events rather than personal stories or images that photovoice or story circles may trigger. The types of images captured for this project were mainly physical or natural structures in the community that elicited knowledge about institutional or collective experiences.26,28 Third, our partnership understood photo-elicitation to be a method consistent with CBPR principles. The process allowed community members to actively engage in the identification and examination of what is happening or has happened concerning, education or employment in the African American community in Pemiscot County and how community health is impacted.26–27

METHOD

The purpose of conducting photo-elicitation was to under stand how the limitation of opportunities for education and employment influence community health. There are a number of frameworks that link these determinants to health.29–31 However, the frameworks tend to be complex and difficult to understand outside of an academic context. After discussion around frameworks, the MOTM partnership chose a framework that seemed easier to understand and had been used in rural, historically agricultural settings.

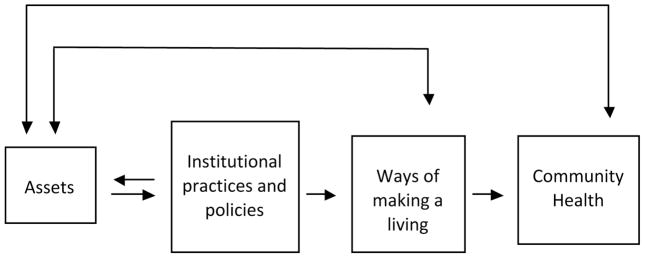

The partnership chose a modified version of the Sustainable Livelihoods framework (Figure 1)32 to frame questions around the photographs. The Sustainable Livelihoods framework was developed to examine how communities achieve health and well-being in developing countries through an economic development lens.32 To the partnership’s knowledge, this framework has not been used in the United States.

Figure 1.

Modified Sustainable Livelihoods Framework32

Although the terminology is different, the partnership saw this framework as a way to examine how the distribution of social determinants of health, which have been described as the social, economic, and political resources and structures within communities,33,34 is shaped and how this influences community health. Communities with high poverty have used the framework to understand how livelihoods (i.e., ways of making a living) are shaped by community assets (one of which is education), institutional practices, and policies and the ways these relationships shape community health.32 The model suggests that, when educational opportunities and resources are low, policies and practices, ways of making a living, and community health are affected differently. Yet, the degree to which each of these variables influences and is influenced depends on the specific community.

The MOTM partnership chose this model for several reasons. Although the United States is not a developing nation, the poverty present in Pemiscot County, especially among African Americans, and the rural geography may create similar challenges. Also, the Sustainable Livelihoods framework has been used to engage disenfranchised members of these communities as participants in the analysis process. Using participatory approaches, like photo-elicitation, within a Sustainable Livelihoods framework serves to involve community members in the analysis of the structures and processes that affect their lives and empower them to work with outside partners to address the root issues.32 The use of photographs as prompts in photo-elicitation provides a visual trigger of community structures and processes. The partnership determined that this methodology fit with the framework because it would challenge participants to step beyond personal experiences to community history and context.

A photographer with limited knowledge of the area took the photographs of Pemiscot County. The team invited the photographer because of his photography expertise. The photographer was asked to capture images that primarily catalogued physical (e.g., school building) or natural (e.g., river) structures in the community as opposed to social images (i.e., people). The partnership developed a list of sites to capture and a community member guided the photographer to these sites. As the photographer and community member discussed the purpose of the images, the community member suggested other structures important to education and employment that needed to be captured. Having a community member guide the photographer to important sites within the community is an example of member checking. Member checking ensures that researchers’ assumptions about what is important or accurate is being tested throughout the qualitative research process.35

The photographer took approximately seventy photographs. Fourteen of those images were used in the photo-elicitation process. The partners chose photographs based on how well they captured education and employment issues. For example, the photographer took photographs of a cemetery. Although generally important to understanding the community’s history, the cemetery photographs were not specific to education or employment. Therefore, the partners did not select those images. The photographs were presented in black and white.

Community partners identified and recruited a convenience sample of African-American men and women. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 71 years of age. All participants were residents of Pemiscot County for at least 15 years with a mean of 36 years. Community partners identified individuals that could add rich information about education and employment within the county. Approximately 80% of the participants had a high school equivalency and/or some college and 60% of the participants were employed for wages. Before the interviews, community partners recommended that men and women have had different experiences within the educational and employment systems and may feel more comfortable discussing these experiences without the presence of the opposite gender. Therefore, men and women met separately. Additionally, two main towns are located in Pemiscot County, Hayti and Caruthersville. The towns are demographically similar; however, a separate school district serves each town. Therefore, to identify issues specific to township, residents from each town met separately. Twenty-four community members participated in the photo-elicitation interviews. Six women and five men from Hayti participated, and seven women and six men from Caruthersville participated.

The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board approved the photo-elicitation interviews. Each photo-elicitation session lasted approximately 90 minutes. With the participants’ permission, the interviews were audio taped for transcription and analysis. The community members participating completed a short demographic questionnaire that included age, educational level, job status, income level, and work history. Two academic partners trained in photo-elicitation facilitated interviews, whereas three community partners participated in the dialogue. The partnership decided that participation by partners in these ways was a benefit. First, academic facilitators were able to probe and explore the unspoken assumptions of community members. This allowed for the naming of root factors that community participants may consider common knowledge. Second, by participating in the dialogues, community partners created a safe environment for disclosure and openness. This is important because research suggests that community participants are more likely to give honest responses and raise questions of researchers when relationships and trust have been established.35

Each photo-elicitation group met twice, once to discuss education and once to discuss employment. For each photo-elicitation session, the group was shown six to eight photographs. The facilitators presented the photographs in two phases. The first phase included three to four photographs assumed to elicit the educational challenges within the county; the second phase included three to four photographs assumed to reflect educational strengths or opportunities. Facilitators gave each community participant a set of the first phase of photographs. Facilitators asked the participants to review the photographs and reflect on what the photographs mean to him or her.

After the initial five 5 minutes of reflection, a facilitator led community participants through a structured dialogue. The structured dialogue asked community participants to describe, explain, and synthesize the information in the photographs.25 Similar to a focus group, the facilitators allowed dialogue to flow based on issues elicited from the photographs and questions the facilitators raised. Interviewers asked questions guided by the Sustainable Livelihoods framework (Table 1). With this framework as a guide, community members were prompted to discuss education and educational opportunities, and how the presence and absence of these opportunities influence community health. Specifically, it asked community participants to reflect on community assets and institutional policies and practices that influenced education and educational opportunities for African Americans in Pemiscot County and the ultimate impact on health. During a second meeting, the facilitators repeated the process with the second phase of photographs depicting images assumed to capture aspects of employment. Throughout the process, the facilitators used member checking, which entailed asking community participants to clarify or provide more information to challenge facilitator’s assumptions.35

Table 1.

Photo-Elicitation Protocol Questions

| Main Question |

|---|

| 1. What do you see in the photographs? |

| 2. What do the photographs mean to you or the community? |

| 3. Do the photographs represent parts of a community that are growing or decaying? |

| 4. What is it about the picture that indicates growth or decay? |

| 5. What are the things that contribute to growth or decay? |

| a. Is there anything about the way people or organizations interact that contributed to this? |

| b. Is there anything about the natural environment (e.g., trees, river, hills, weather) or the physical environment (e.g., streets, housing, sewer system) that contributed to this? |

| c. Is there anything about the infrastructure (e.g., transportation or communication—telephones) that contributed to this? |

| d. Is there anything about finances (e.g., money or lack of money) that contributed to this? |

| 6. Policies can be thought of as rules that are formal and informal ways of regulating our behavior. For example, “no smoking” policies are rules that control where we smoke. These policies can be put in place by the state (formal) or business owners (informal). Supervisors within a business may determine how rules are enforced. This is considered a practice. Thinking about the growth or decay what kinds of policies and practices may have contributed? |

| 7. What are the potential consequences of this growth or decay? |

| 8. What are the potential health consequences of this growth or decay? |

| 9. How was this situation different in the past? |

| 10. Did the photographs represent community strength or challenge 20 years ago? |

Figures 2 and 3 are photographs used in the photo-elicitation interviews about education, specifically educational challenges. The figures represent the type of pictures taken. The participants described the photographs as follows. The community participants described Figure 2 in this way: “Central was the Negro school. What they called the Negro school. It was all blacks before they integrated.” The community participants said the photograph represents “abandonment.” The community participants described Figure 3 as “Mathis Elementary” and said it “is more or less kept up. More or less kept in a better condition towards where it’s located at.” The community participants noted that Figure 3 is located “in a white neighborhood.”

Figure 2.

African American School Memorial

Figure 3.

White School Memorial

Analysis

Academic staff transcribed the tapes verbatim, reviewed each transcript for errors, and made corrections where appropriate before beginning analysis. Atlas.ti, a qualitative analysis software package,36 was used to facilitate management, coding, and sorting of data. Focused coding, using a start list based on the Sustainable Livelihoods framework, provided the structure for analysis. The start list included codes for assets, institutional practices and policies, ways of making a living, and health. All coding decisions were documented to provide a record, or audit trail, of the data analysis process.35,37 Once the codes were finalized and quotes were appropriately assigned, matrices were developed. Matrices are data display tools used to understand relationships or patterns in the data and aid in drawing conclusions about data.37 Using the matrices, academic staff wrote summaries for each code and identified the relationships between codes. MOTM academic and community partners reviewed the summaries to test the assumptions and conclusions drawn.

Using the Sustainable Livelihoods framework to guide the photo-elicitation process allowed community members to discuss how historical and structural factors have affected health. For example, the synthesis of the photographs in Figures 2 and 3 prompted a conversation about the state of education in Pemiscot County and the impact of segregation and desegregation in Pemiscot County. The participants explained that when schools were integrated, African-American teachers lost their jobs. As the foundation of the African-American middle class, this had significant impact on the local economy in the black community.

When those schools were changed and everything was integrated, the first thing that did not happen is that our black teachers were not given positions. So that put them …. In order to use their college degrees and their education careers they had to leave. So they left. When our black teachers left the communities, our black businesses began to dwindle away. I remember the street I raised my kids on in Caruthersville on 12th street, when I was a kid that street was lined up with businesses and owners and they were all black owned businesses from Walker Ave all the way to Adams.

As a result of the way integration policy was implemented, the African-American community suffered economically and students lost role models. One participant explained that as a child he had a teacher that pushed him in a way that even his parents did not.

Even though my parents backed us up, that was good moral background there, but a teacher that would tell me that if you don’t make a certain grade you in trouble with me.

It is not because I don’t like you. It’s because I’m trying to show you that if you push yourself you can actually become something. And that was a lot of push that I didn’t get from home.

The participants noted that children do not have the basic educational skills needed to succeed today. Part of the reason, the participants explained, is that teachers do not play this role. In fact, the participants remarked that a common institutional practice in Pemiscot County is for a teacher to give a passing grade to an athlete during the athletic season even if the student has not mastered the material. A recent graduate explained how this happened to him.

I had a similar situation when I was in school I was playing football. And, it was American History. The teacher, I really wasn’t understanding what he was saying. I was playing football and knowing I wasn’t knowing no test or nothing but I was passing with B– because I was playing football. So, I got kicked off the football team. As soon as I got kicked off the football team, I got Fs. All Fs.

Participants did not connect the historical and structural factors that affect education and employment to health immediately. Through the photo-elicitation process, the participants were asked to reflect on community assets and institutional policies and practices which lead to a discussion of historical and structural factors (e.g., segregation). Guided by the Sustainable Livelihoods framework, the facilitators asked participants to reflect on how these factors subsequently influence community health. As a result of guiding the photo-elicitation interviews in this way, participants were able to connect underlying issues with education and employment to health. The participants discussed how past and present policies and practices (as noted) have increased the likelihood that children do not acquire the skills needed to succeed. Without these skills, African Americans are less likely to find employment, especially in a rural community. The participants noted that community members cope with the stress of unemployment through unhealthy behaviors (e.g., unhealthy eating, alcohol abuse). These behaviors put people at greater risk for heart disease.

And then if you don’t got a job, you stressed cause you don’t have one. And that’s why you see a lot of people either … that’s why you got black people, you know, either selling, smoking, drinking, young girls having sex getting pregnant at the age of 15, 16. And then, then people look down at the black community like man that’s all they know how to do. I mean and that could be the kid that you know can be smart and change this whole [world] around. But you know it seem like when you try to make a difference somebody treat you like a bug and they step on you and crush you.

Although participants did not connect specific historical and structural factors to health at once, this quote demonstrates that participants were able to articulate how underlying factors, like race and power, disenfranchise low-income African Americans. The participants noted that African Americans in Pemiscot County feel that they cannot create change because they will be crushed trying. This alludes to the notion that African Americans in Pemiscot County are powerless to make change and this disenfranchisement exacerbates stress of joblessness.

CONCLUSION

Photo-elicitation allowed the MOTM partnership to identify factors that affect access to and availability of educational and economic opportunities for African Americans in Pemiscot County, Missouri. Using the Sustainable Livelihoods framework to guide the photo-elicitation process allowed community participants to describe how history has shaped policy and programs related to education and employment and the interconnectedness of issues around education and employment in this rural community. Although research shows education and employment’s link to health, understanding the way community members perceive this relationship within their local context is essential. Developing programs and policies to address heart health cannot be successful if the social, political, economic, and historical contexts are not considered. For example, working to improve dietary intake of African Americans will fail in Pemiscot County if we do not address the fact that eating patterns are shaped by stress and work to understand the community processes and structures that create stress.

Photo-elicitation is a useful technique for stimulating dialogue around social determinants of health and their distribution. The MOTM partners learned two essential things using this method in conjunction with a CBPR approach. First, because the questions arose from the community, there was a desire and commitment on the part of community participants to examine these issues. Second, the trust between community and academic partners fostered through a CBPR approach was essential for this method to be successful. Academic and community partners on this project have been working together in Pemiscot County for over a decade. Building a relationship on the principles of CBPR allowed the MOTM partnership to invite other community members into an environment of trust and to probe for more authentic, explicit explanations of collective events and experiences influencing education, employment, and community health. Using this approach was useful in moving community health work from a menu of activities that address heart disease to the identification of social determinants affecting health and strategies to build a healthier community. For many in Pemiscot County, this is the heart of the matter.

Limitations

Using this approach also raises questions about the academic and community roles in CBPR. For example, photographs were chosen by academic and community partners and taken by an expert photographer. This makes an assumption that the community partners know which images are most compelling and important. The images community members might have captured would have been different and might or might not have elicited dialogue around the structural factors affecting health. Additionally, academic partners facilitated the photo-elicitation process whereas community partners participated in the dialogue. If the community partners had facilitated the dialogue, the direction might have been different. The community partners might have been more attuned to unspoken knowledge about a topic and, therefore, probed dialogue more effectively. On the other hand, community partners might have probed on issues of individual importance because it can be difficult to separate personal experiences and salience from community salience. In light of this, it is important to check assumptions made. For instance, it cannot be assumed that community members desire to participate in all phases of the research process when they are not part of the working partnership and are minimally compensated for their time. In the same vein, it is important to acknowledge that the choice made about facilitation or participation may produce different results, not necessarily better.

As the reflection, dialogue, and action cycle continues, MOTM is considering the best way to share findings from this process with the larger community. Working together for many years, the MOTM partners have learned that reports and didactic presentations to the larger community may fulfill requirements of funding agencies but do not engage the community in a way that promotes action. Collectively, the MOTM partners are working to develop a medium for dissemination that is meaningful, participatory, and seeks to engage community members to promote community action. Taking a cue from this visual methodology, the MOTM partnership is working on an audiovisual medium that will continue to engage the community in dialogue about root determinants and move toward action to address them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William True, the photographer, who worked with us to produce the images used. We thank Marjorie Sawicki who provided thoughtful review of this manuscript. Finally, we thank all of the community participants who contributed to the photo-elicitation process.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

References

- 1.Brownson C, Smith C, Pratt M, Mack NE, Jackson-Thompson J, Dean CG, et al. Preventing cardiovascular disease through community-based risk reduction: The Bootheel Heart Health Project. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(2):206–13. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M. Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Rep. 2000 May/June;115:191–7. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health. 2001;14(2):182–97. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman J. The case for more active policy attention on health promotion. Health Aff. 2002;21(2):78–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams D. Patterns and causes of disparities in health. In: Mechanic D, Rogut L, Colby D, Knickman J, editors. Policy challenges in modern health care. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culter D, Lleras-Muney A. Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006. Jul, pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross C, Mirowsky J. Refining the association between education and health: The effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography. 1999;36(4):445–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deaton A, Paxson C. Mortality, income, and income inequality over time in Britain and the United States. Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnittker J. Education and the changing shape of the income gradient health. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45(3):286–305. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dooley D, Fielding J, Levi L. Health and unemployment. Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:449–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.17.050196.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin R, Shah C, Svoboda T. The impact of unemployment on health: A review of the evidence. CMAJ. 1995;153(5):529–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathers C, Schofield D. The health consequences of unemployment: The evidence. MJA. 1998;168:178–82. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1998.tb126776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martikainen PT. Unemployment and mortality among Finnish men 1981–5. BMJ. 1990;301:407–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross C, Wu C. The links between education and health. Am Soc Rev. 1995;60(5):719–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turner BJ. Economic context and the health effects of unemployment. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:213–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee-Ryan F, Kinicki A, Song Z, Wanberg C. Psychological and physical well being during unemployment: A meta-analysis study. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(1):53–76. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis L, Ajzen I, Saunders J, Williams T. The decision of African American students to complete high school: An application of theory of planned behavior. J Educ Psychol. 2002;94(4):810–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hooks B. We real cool: Black men and masculinity. New York: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.James S. Confronting the moral economy of US racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):198. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Introduction to community empowerment, participatory education, and health. Health Educ Behav. 1994;21(2):141–8. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallerstein N, Duran B. The theoretical, historical, and practice roots of CBPR. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcome. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 26–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Seabury Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Burris M. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–87. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labonte R, Feather J, Hills M. A story/dialogue method for health promotion knowledge development and evaluation. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(1):39–50. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harper D. Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies. 2002;17(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurworth R, Clark E, Martin J, Thomsen S. The use of photo-interviewing: Three examples from health evaluation and research. Evaluation Journal of Australasia. 2005;4(1/2):52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark-Ibanez M. Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. Am Behav Sci. 2004;47(12):1507–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger N. Ladders, pyramids and champagne: The iconography of health inequities. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2008;62:1098–104. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson LM, Schimshaw SC, Fullilove M, Fielding JE the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The community guide’s model for linking the social environment to health. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3S):12–20. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of International Development. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets [monograph on the Internet] 2007 [cited 7 Apr 2006]. Available from: http://www.livelihoods.org/info/guidance_sheets_pdfs/section2.pdf.

- 33.Brennan Ramirez L, Baker EA, Metzler M. Promoting health equity: A resource to help communities address social determinants of health. Bethesda (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhr R. User’s manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software. Berlin: Development GmbH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]