Abstract

Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen in humans, causing both debilitating mucosal infections and potentially life-threatening systemic infections1,2. Until recently, C. albicans was thought to be strictly asexual, existing only as an obligate diploid. A cryptic mating cycle has since been uncovered in which diploid a and α cells undergo efficient cell and nuclear fusion, resulting in tetraploid a/α mating products (refs. 3–6). Whereas mating between a and α cells has been established (heterothallism), we report here two pathways for same-sex mating (homothallism) in C. albicans. First, unisexual populations of a cells were found to undergo autocrine pheromone signalling and same-sex mating in the absence of the Bar1 protease. In both C. albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bar1 is produced by a cells and inactivates mating pheromone α, typically secreted by α cells7–10. C. albicans Δbar1 a cells were shown to secrete both a and α mating pheromones; α-pheromone activated self-mating in these cells in a process dependent on Ste2, the receptor for α-pheromone. In addition, pheromone production by α cells was found to promote same-sex mating between wild-type a cells. These results establish that homothallic mating can occur in C. albicans, revealing the potential for genetic exchange even within unisexual populations of the organism. Furthermore, Bar1 protease has an unexpected but pivotal role in determining whether sexual reproduction can potentially be homothallic or is exclusively heterothallic. These findings also have implications for the mode of sexual reproduction in related species that propagate unisexually, and indicate a role for specialized sexual cycles in the survival and adaptation of pathogenic fungi.

The hemiascomycetous fungi are a diverse range of species that include the prototypical model yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as well as the prevalent human pathogen, Candida albicans. Sexual reproduction in both fungi is driven by the secretion of sex-specific pheromones that promote mating between partners of the opposite sex11–13. Pheromone gradients are sensed by G-protein-coupled cell-surface receptors that initiate the mating response14,15. C. albicans mating is thought to be exclusively heterothallic, whereas isolates of S. cerevisiae that express HO endonuclease are homothallic because of mating-type switching16. The discovery that unisexual populations of C. albicans can express both a and α mating pheromones 17 led us to test whether autocrine pheromone signalling and homothallism can occur in this species.

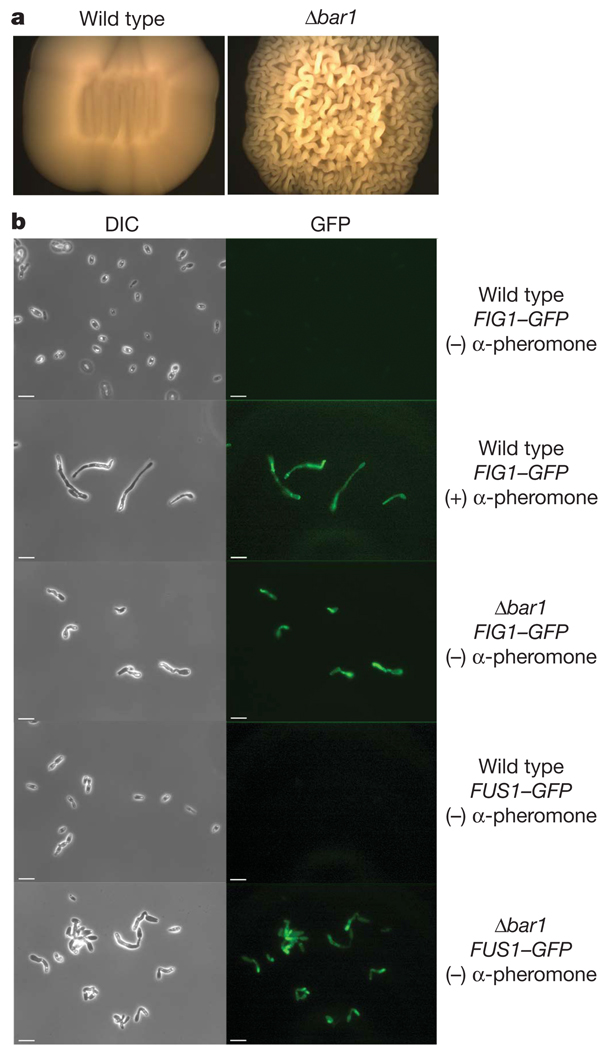

C. albicans a cells derived from the laboratory strain SC5314 were treated with synthetic α-pheromone and the quantitative polymerase chain reaction used to compare the induction of both a- and α-pheromone genes (MFa, and MFα, respectively). Opaque-phase cells were used for these experiments, as these are the mating-competent form of C. albicans 6. Both MFa (300-fold) and MFα (373-fold) were highly induced in response to α-pheromone, in contrast to S. cerevisiae where only a-pheromone is upregulated18. In both C. albicans and S. cerevisiae, an extracellular barrier activity acts to antagonize the function of α-pheromone. The activity, encoded by BAR1, is an aspartyl protease that cleaves α-pheromone, inactivating it7–10. We therefore analysed a C. albicans Δbar1 mutant to determine whether α-pheromone production has a functional role in these cells. C. albicans Δbar1 cells exhibited distinctive colony morphologies when cultured on solid media. Mutant colonies appeared increasingly wrinkled during growth on yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium (Fig. 1a). Cells retrieved from these colonies were highly elongated and showed similarities to cells that had undergone extended exposure to pheromone12. To confirm that elongated cells were undergoing a mating-type response and were not hyphal (filamentous) cells, green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporters were introduced under the control of pheromone-specific promoters. Both FIG1 and FUS1 genes are highly expressed in response to pheromone17, and pFIG1-GFP and pFUS1-GFP constructs were therefore used to monitor activation of the mating program. Significantly, both FIG1 and FUS1 expression was induced, confirming that cells were undergoing a mating-like response, even in the absence of exogenous pheromone or a mating partner of the opposite sex (Fig. 1b). To confirm that this phenomenon was not limited to strains derived from SC5314, Δbar1 mutants were also generated in P37005, a natural a/a isolate of C. albicans, and found to exhibit similar cell and colony phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Deletion of BAR1 results in an autocrine mating response.

a, Patches of wild-type and Δbar1 a cells after 4 days growth on YPD medium. b, Mating response of wild-type and Δbar1 a cells with and without α-pheromone in Spider medium for 36 h. Differential interference contrast (DIC, left) and GFP fluorescence (GFP, right) images are shown. Induction of the mating response was monitored using GFP reporters under the control of the mating-response genes FIG1 or FUS1. All C. albicans cells used in this study were in the opaque phase as this is the mating-competent form of the organism6,30. Scale bars, 16 µm.

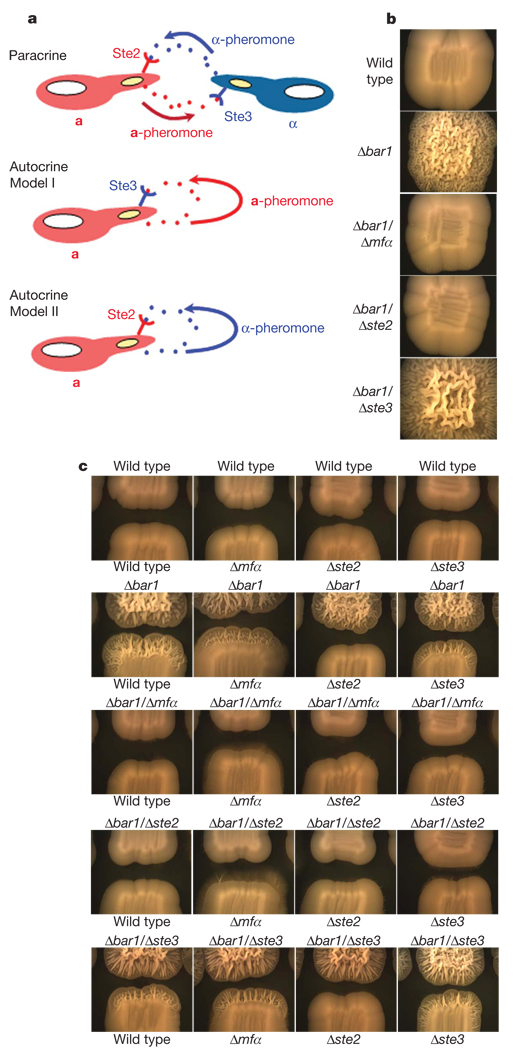

Two models were considered for how autocrine pheromone signalling could lead to activation of a mating response. First, a-pheromone secretion could signal to Ste3, the receptor for a-pheromone (Fig. 2a, model I). Alternatively, α-pheromone could induce mating via binding to Ste2, the receptor for α-pheromone (model II). Although not mutually exclusive, these two models were tested by construction of strains lacking different combinations of pheromone or pheromone receptor genes. Significantly, loss of either α-pheromone (MFα) or its receptor (Ste2) completely abolished the wrinkled colony appearance of Δbar1 a strains (Fig. 2b). In contrast, loss of STE3 (encoding the receptor for a pheromone) had no effect on colony phenotype (Fig. 2b). Thus, autocrine signalling in a cells is driven by α-pheromone production and requires the presence of Ste2, the cognate receptor for α-pheromone (model II).

Figure 2. Autocrine signalling in C. albicans a cells.

a, Model of conventional paracrine signalling between a and α cells and two models for autocrine signalling. Note that ‘autocrine’ signalling is used here to refer to signalling within populations of a cells. b, C. albicans a cells after 4 days growth on YPD medium. Whereas Δbar1 strains showed a highly wrinkled morphology, reconstituted strains in which the BAR1 gene had been reintegrated did not show wrinkling (not shown). c, Demonstration of autocrine signalling among different populations of a cells after 4 days growth on YPD medium. Wrinkling at the edge of a test colony is indicative of autocrine signalling.

Autocrine pheromone signalling was also observed between neighbouring colonies of cells, as Δbar1 a cells induced a response in adjacent colonies of a cells. Cells from wrinkled colonies again exhibited polarized growth indicative of a mating response (data not shown). Neighbouring cells failed to respond in the absence of STE2, indicating that signalling required the receptor for α-pheromone (Fig. 2c, row 2). Furthermore, Δbar1 cells were unable to induce a response in adjacent cells if either MFα or STE2 was also deleted (Fig. 2c, rows 3 and 4). The dependence of signalling on STE2 is demonstrative of a positive feedback loop in these cells; α-pheromone secreted by Δbar1 cells binds to Ste2 receptors on these cells and results in further augmentation of pheromone production. Only when this feedback loop is in effect does pheromone secretion reach the levels necessary for autocrine signalling. STE3, encoding the receptor for a-pheromone, was not involved in this signalling (Fig. 2c, column 4 and row 5). Production of α-pheromone by Δbar1 a cells was also evident in halo assays and was shown to increase biofilm formation by these cell types (see Supplementary Information).

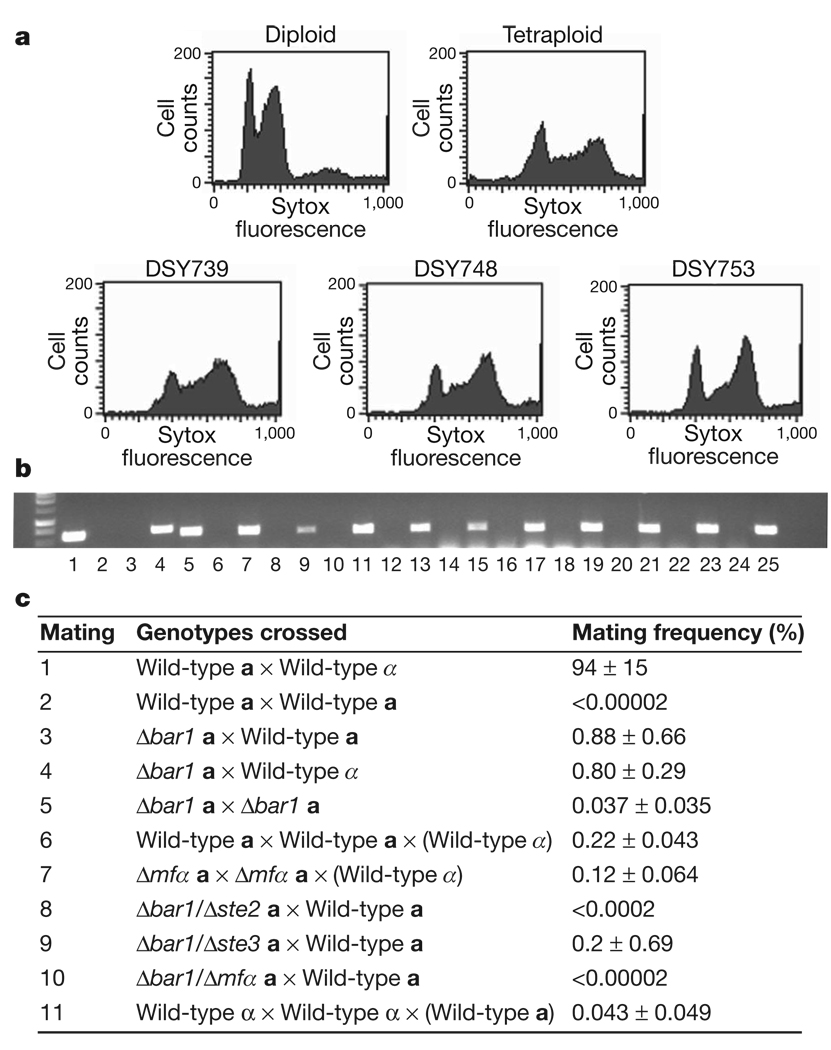

The existence of a robust autocrine mating pathway led us to test whether C. albicans is capable of homothallic mating. Two different auxotrophic Δbar1 strains were mixed and co-incubated on Spider medium for 3 days. Cells were recovered from the mating mixture and plated onto selective medium to detect potential a–a mating products. A number of prototrophic mating products were obtained and analysis by PCR and flow cytometry revealed that these were stable tetraploid cells of mating type a (Fig. 3a, b). To compare the frequency of homothallic and heterothallic mating in C. albicans, several quantitative mating crosses were performed (Fig. 3c). Mating between wild-type a and α cells occurred efficiently (94%), whereas no mating was observed between two wild-type a strains (<0.00002%). Significant levels of unisexual mating were obtained, however, using two Δbar1 a strains (0.037%), an increase of more than 1,850-fold over wild-type a–a mating. The efficiency of unisexual mating was further increased in crosses between Δbar1 and wild-type a strains, with 0.88% of cells undergoing mating, an increase of more than 40,000-fold over that between wild-type a strains (Fig. 3c). In fact, Δbar1 a cells mated as efficiently with other a cells as with α cells (0.80%), indicating a loss in sexual preference for one mating-type partner over the other. These experiments demonstrate that mating can take place even within unisexual populations of C. albicans cells, and that Bar1 acts to limit these types of self-fusion events. Notably, mating between wild-type a cells also occurred at an appreciable frequency (0.22%) if co-cultured with α cells. In these ménage à trois matings, α cells presumably provided levels of α-pheromone that were sufficient to overcome Bar1 activity and drive a–a mating. Levels of α-pheromone may be augmented by autocrine pheromone signalling in a cells, as deletion of MFα in a cells led to a slight reduction in the frequency of ménage à trois mating (0.12%). In addition, α cells did not need to be in contact with a cells to drive same-sex mating (Supplementary Fig. 4). Mating between wild-type α cells (0.043%) was similarly observed when co-cultured with a cells (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Homothallic mating in C. albicans.

a, Flow cytometric analysis indicating the tetraploid content of progeny isolated from a–a matings. The x-axis of each graph (Sytox) represents a linear scale of fluorescence and the y-axis (Cell counts) a linear scale of cell number. For analysis of additional same-sex mating products see Supplementary Fig. 6. b, PCR confirming the mating type of a–a mating products using primers directed at OBPa and OBPα. Odd-numbered lanes are OBPa reactions, whereas even-numbered lanes are OBPα reactions. Lanes 1, 2 and 3, 4 are control reactions for a and α cells, respectively. c, Table of mating frequencies for different genetic crosses. Values are listed as mean frequency ± s.d.

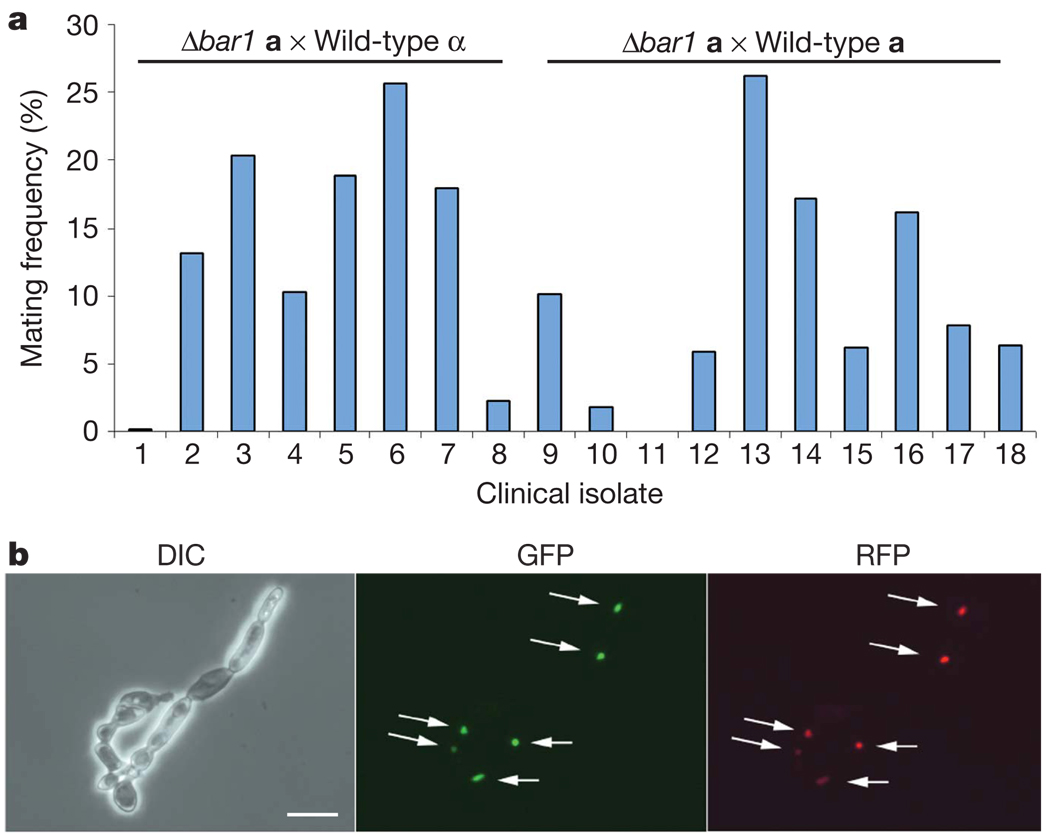

If self-mating in unisexual populations is a direct consequence of autocrine pheromone signalling, then mutants deficient in signalling should be unable to self-mate. Both Δbar1/Δste2 and Δbar1/Δmfα a strains did not exhibit autocrine signalling and also showed no detectable mating with wild-type a strains (<0.0002%; Fig. 3c). In contrast, Δbar1/Δste3 a strains were competent for both autocrine signalling and unisexual mating (1.2%). The potential for unisexual mating is therefore dependent on the ability of cells to undergo autocrine pheromone signalling. To examine the efficiency of inbreeding and outbreeding by different C. albicans strains, SC5314 Δbar1 a strains were also mated with different clinical isolates (Fig. 4a). Again, Δbar1 strains mated with both a and α isolates at a similar frequency (average of 9.8% and 17.6%, respectively). In fact, mating was generally more efficient between SC5314 and clinical isolates (up to 26% a–a mating) than that between SC5314 strains alone. Mating zygotes could be detected in unisexual crosses and fluorescent labelling of the nuclei confirmed that karyogamy had taken place (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 5). The tetraploid products of unisexual mating were generally stable, but could be induced to undergo chromosome loss to produce diploid cells, thereby completing a parasexual mating cycle (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Figure 4. Homothallic mating across clades in C. albicans.

a, Mating frequencies of an SC5314 Δbar1 a cell crossed with naturally occurring isolates from different clades of C. albicans. 1–8 are crosses between Δbar1 a cells and clinical α cells. 9–18 are crosses between Δbar1 a cells and clinical a cells. For a complete list of strains see Methods. b, Mating zygote formed between a Δbar1 a cell derived from SC5314 (DSY906, expressing HTB–RFP; histone H2B gene–red fluorescent protein) and a clinical a cell derived from IHEM16614 (DSY908, expressing HTB–YFP). Arrows indicate fused nuclei expressing both fluorescent proteins. DIC (left), YFP fluorescence (observed using the GFP channel, middle) and RFP fluorescence (right) images are shown. Scale bar, 15 µm.

Our findings have implications for sexual reproduction in C. albicans and related species, as they reveal a mechanism for same-sex mating in hemiascomycetes. In C. albicans, heterothallic mating between a and α cells can occur, yet a predominantly clonal population structure suggests that outbreeding is rare19. The discovery of self-mating indicates that homothallism could act to create a burst of genetic diversity by increasing recombination within unisexual populations. Completion of the parasexual cycle could promote allele shuffling or increase karyotypic variation within the diploid genome. Furthermore, isolates of some related species are thought to be exclusively homothallic. For example, isolates of Lodderomyces elongisporus are able to form asci from identical cells, yet the genome apparently encodes only one pheromone gene (MFα) and one receptor gene (STE2)20. Discovery of autocrine signalling and self-mating reveals a mechanism by which such species could reproduce sexually despite the absence of mating partners of the opposite sex.

Homothallism has been well characterized in S. cerevisiae where it is a direct result of mating-type switching. C. albicans and related species are unable to undergo mating-type switching, yet we demonstrate two potential pathways by which self-mating can occur. First, inhibition of Bar1 activity promotes autocrine signalling and mating within unisexual populations of C. albicans. We hypothesize that certain niches in the mammalian host will favour self-fertilization by downregulating Bar1 activity. Second, we show that same-sex mating can occur because of pheromone signalling in conventional a–α mixes. In this case, pheromone secretion by even a limiting number of α cells can promote a–a mating (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, certain combinations of C. albicans a and α strains are incompatible for heterothallic mating as nuclei fail to undergo karyogamy21. Our results show that pheromones produced during contact between two such ‘infertile’ strains could still result in self-mating within sexes.

The program of same-sex mating in C. albicans shows unexpected similarities to that in other human fungal pathogens. In the basidio-mycetous fungus Cryptococcus neoformans mating between a and α isolates can occur, yet clinical and environmental isolates are over-whelmingly of the α mating type. Same-sex mating between α isolates of C. neoformans has been observed both in the laboratory and in the wild, and is thought to be the predominant mode of sexual reproduction in this organism22–25. Pneumocystis carinii is another fungal pathogen predicted to undergo a modified sexual cycle involving cells of the same mating type26. It thus seems that autocrine pheromone signalling and homothallism may be traits shared by a diverse group of medically relevant fungi. These pathogens have retained the ability to undergo sexual reproduction and yet have evolved modifications to these programs that support their survival and propagation. Elucidating the respective mechanisms of homothallism and heterothallism will therefore be critical to the understanding of these species as human pathogens.

METHODS SUMMARY

C. albicans strains were derived from SC5314 except where otherwise noted. Mutant strains were created using either the PCR fusion or SAT1 flipper methods described previously27,28. For a complete list of strains and primers see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Media were made as described previously10. All C. albicans cells used in this study were in the opaque phase as this is the mating-competent form of the organism6. Quantitative PCR was performed on a cells that had been treated with 10 µg ml−1 α-pheromone for 4 h in Spider medium, as described previously10,29. For analysis of colony morphology, patches of C. albicans cells (~0.5 cm2) were spaced 0.75 cm apart on YPD medium and imaged after 4 days growth at 30 °C using a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C stereoscope with an Infinity 1 camera. Cells were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu-ORCA camera. Mating frequencies were determined by mixing 2 × 107 cells of differently marked auxotrophic strains on Spider medium and incubating at room temperature for 3 days. Cells were then resuspended in water and plated onto selective media to determine frequency of mating products10. For analysis of a–a mating in the presence of α cells, 2 × 107 cells of each of three strains were mixed and incubated on Spider medium (two differently marked a strains and an α strain negative for both markers). Cells were recovered and analysed as above. The same strategy (two differently marked α strains and an a strain negative for both markers) was applied to detect α–α mating. Flow cytometry to determine cell ploidy was performed by staining DNA with Sytox Green and analysis on a FACSCalibur4. PCR to determine mating type was performed using primers directed at OBPa/α as described previously30.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank D. MacCallum and the Aberdeen Fungal Group for strains, and J. Laney, T. Serio, R. Sherwood and M. Tessmer for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank D. Koveal and S. Gilman for assistance during the preliminary stages of this work. R.J.B. holds an Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. K.A. was supported by a training grant for Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions K.A. constructed mutant strains, analysed mating phenotypes, quantified mating frequencies and performed biofilm assays. D.S. constructed mutant strains, quantified mating frequencies and performed biofilm and halo assays. R.J.B. constructed mutant strains, quantified mating frequencies, performed adherence assays and analysed mating zygotes. K.A. and R.J.B. were involved in study design and writing of the manuscript.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Samaranayake LP, et al. Fungal infections associated with HIV infection. Oral Dis. 2002;8 Suppl. 2:151–160. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.8.s2.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisplinghoff H, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hull CM, Johnson AD. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science. 1999;285:1271–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magee BB, Magee PT. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLα strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MG, Johnson AD. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell. 2002;110:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00837-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks JB, Herskowitz I. Evidence for a new diffusible element of mating pheromones in yeast. Nature. 1976;260:246–248. doi: 10.1038/260246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacKay VL, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae BAR1 gene encodes an exported protein with homology to pepsin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:55–59. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manney TR. Expression of the BAR1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: induction by the α mating pheromone of an activity associated with a secreted protein. J. Bacteriol. 1983;155:291–301. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.1.291-301.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer D, Cote P, Whiteway M, Bennett RJ. Barrier activity in Candida albicans mediates pheromone degradation and promotes mating. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:907–918. doi: 10.1128/EC.00090-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett RJ, Uhl MA, Miller MG, Johnson AD. Identification and characterization of a Candida albicans mating pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8189–8201. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8189-8201.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockhart SR, Daniels KJ, Zhao R, Wessels D, Soll DR. Cell biology of mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2003;2:49–61. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.1.49-61.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panwar SL, Legrand M, Dignard D, Whiteway M, Magee PT. MFα1, the gene encoding the α mating pheromone of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2003;2:1350–1360. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1350-1360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson CL, Hartwell LH. Courtship in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: an early cell-cell interaction during mating. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:2202–2213. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segall JE. Polarization of yeast cells in spatial gradients of α mating factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8332–8336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall MN, Linder P. The Early Days of Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. The role of nutrient regulation and the Gpa2 protein in the mating pheromone response of C. albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;62:100–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts CJ, et al. Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science. 2000;287:873–880. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odds FC, et al. Molecular phylogenetics of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:1041–1052. doi: 10.1128/EC.00041-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler G, et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature. 2009;459:657–662. doi: 10.1038/nature08064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett RJ, Miller MG, Chua PR, Maxon ME, Johnson AD. Nuclear fusion occurs during mating in Candida albicans and is dependent on the KAR3 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1046–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser JA, et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–1364. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin X, et al. Diploids in the Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A population homozygous for the α mating type originate via unisexual mating. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000283. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bui T, Lin X, Malik R, Heitman J, Carter D. Isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from infected animals reveal genetic exchange in unisexual, α mating type populations. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1771–1780. doi: 10.1128/EC.00097-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smulian AG, Sesterhenn T, Tanaka R, Cushion MT. The ste3 pheromone receptor gene of Pneumocystis carinii is surrounded by a cluster of signal transduction genes. Genetics. 2001;157:991–1002. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noble SM, Johnson AD. Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:298–309. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.2.298-309.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reuβ O, Vik A, Kolter R, Morschhauser J. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene. 2004;341:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guthrie C, Fink GR. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockhart SR, et al. In Candida albicans, white-opaque switchers are homozygous for mating type. Genetics. 2002;162:737–745. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.