Abstract

Alcohol use health consequences are considerable; prevention efforts are needed, particularly for adolescents and college students. The national minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is a primary alcohol-control policy in the United States. An advocacy group supported by some college presidents seeks public debate on the minimum legal drinking age and proposes reducing it to 18 years.

We reviewed recent trends in drinking and related consequences, evidence on effectiveness of the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years, research on drinking among college students related to the minimum legal drinking age, and the case to lower the minimum legal drinking age.

Evidence supporting the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is strong and growing. A wide range of empirically supported interventions is available to reduce underage drinking. Public health professionals can play a role in advocating these interventions.

SINCE 1984 THE NATIONAL minimum legal drinking age in the United States has been 21 years. During the intervening 25 years there have been periodic efforts to lower the minimum legal drinking age, including recent legislation introduced in 7 states, although none of these bills have been enacted. In 2008 a group of university and college presidents expressed their discontent with the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years by signing on to the Amethyst Initiative, a much publicized advocacy effort to encourage public debate about lowering the drinking age. This group of college presidents, and their partner organization, Choose Responsibility, propose reducing the minimum legal drinking age to 18 years. This policy change is a central feature of a campaign its organizers contend will help young adults aged 18 to 20 years make healthy decisions about alcohol and lead to reductions in drinking and its negative effects. Because the consequences of alcohol use are considerable, and changes in the minimum legal drinking age may have important ramifications for health and safety, this issue requires serious consideration and participation from the public health community.

ALCOHOL AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Alcohol consumption is the third leading actual cause of death in the United States, a major contributing factor to unintentional injuries, the leading cause of death for youths and young adults, and accounts for an estimated 75 000 or more total deaths in the United States annually.1–3 Alcohol use is associated with a wide range of adverse health and social consequences, including physical and sexual assault, unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, violence, vandalism, crime, overdose, other substance use, and high-risk behavior, resulting in a heavy burden of social and health costs.2,4,5 Drinking alcohol most commonly begins during adolescence and early initiation of alcohol use is associated with alcohol problems in adulthood.6,7 Underage drinkers drink on fewer occasions, but when they drink they are more likely to binge drink.8,9 In recognition of the harms caused by underage drinking the US Surgeon General issued a Call to Action in 2007 to prevent and reduce drinking among youths.5

MINIMUM LEGAL DRINKING AGE IN THE UNITED STATES

Minimum legal drinking age laws have been a primary alcohol-control strategy in the United States for 75 years. When the 21st Amendment to the US Constitution repealed Prohibition in 1933, most states set a minimum legal drinking age of 21 years, although the specific provisions of the law in each state varied.10 These laws began to change in the 1970s when many states lowered the minimum legal drinking age along with reducing the minimum age to vote during the Vietnam War.11

The lower minimum legal drinking age was followed by increases in the sale and consumption of alcohol and in alcohol-involved traffic fatalities, particularly among young adults aged 18–20 years.12–14 On the basis of these unintended health consequences of the lower drinking age, some states reinstated the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years.15 By the early 1980s, this situation created a patchwork of differential legal restrictions across states and contributed to the problem of underage youths in states with a minimum legal drinking age of 21 years driving to states with a lower minimum legal drinking age to purchase and consume alcohol. In direct response to these concerns, Congress and President Ronald Reagan worked to create a consistent national drinking age. The National Minimum Drinking Age Act became law in 1984, requiring that states prohibit the purchase and public possession of alcohol for persons aged younger than 21 years in order to receive all of their federal highway funds.16 By 1988 all states had a minimum legal drinking age of 21 years.

TRENDS IN ALCOHOL USE AND RELATED PROBLEMS

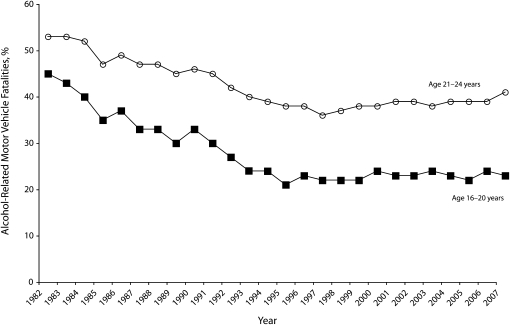

Overall in the United States, alcohol consumption, heavy drinking, and daily alcohol use have declined among young adults aged 18–20 years since the early 1980s, whereas shifts in drinking behavior among young adults aged 21 to 24 years have been more gradual and less consistent.17,18 Increases in binge drinking have been observed among young adults aged 21–24 years in the past decade, but drinking among those aged 18–20 years has remained stable during this time period for both college students and their peers who were not in college.19 Consistent with declining trends in consumption, the percentage of traffic fatalities involving alcohol declined dramatically from the early 1980s (when reliable national data first existed) through 1997, when rates leveled off.13 Figure 1 shows these national trends in alcohol-involved motor vehicle fatalities for youths aged 16 to 20 years and those aged 21–24 years with data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Analysis Reporting System, a census of deaths from traffic fatalities in the United States.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of alcohol-related motor vehicle fatalities among young adults aged 16 to 24 years, by age group: United States, 1982–2007.

Source. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Fatality Analysis Reporting System.

COLLEGE STUDENTS AND THE MINIMUM LEGAL DRINKING AGE

Although heavy drinking among older adolescents and young adults has declined over the past decades, no such declines have occurred among college students.17,18,20,21 College students are more likely to engage in heavy drinking than their peers who do not attend college,19,22–24 with 2 in 5 students nationally engaging in binge drinking on at least 1 occasion in the past 2 weeks.18,21 Approximately three quarters of college students aged 18–20 years drank alcohol in the past year, although they are less likely than their peers of legal drinking age to drink and to engage in binge drinking.8,19 The heaviest-drinking college students are more likely to have been heavy drinkers in high school.25–29

College students are heavy drinkers as a group, but drinking behavior varies widely by college.30,31 College environments that afford easy access to low-cost alcohol, have few policies restricting accessibility to alcohol, and have lax enforcement of existing policies create the conditions for heavy drinking among college students.8,30,32–43 The Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities Act requires college administrators to enforce the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years, a restriction that targets approximately half of the traditional college student population. However, surveys of college administrators indicate that enforcement of alcohol policies at most colleges is limited, and colleges tend to focus their prevention efforts on educational programs for students.44,45 One national survey found that fewer than 1 in 10 underage students who drink alcohol reported experiencing any consequences for violating alcohol policies imposed by their college.8

Although the level of enforcement of the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is low nationally, enforcement and comprehensiveness of policy restrictions do make a difference. At colleges where campus security strongly enforces the alcohol policy, students perceive the stronger enforcement efforts and are less likely to binge drink.34 Underage students who attend college in states with a comprehensive set of control policies restricting underage drinking are less likely to binge drink than underage students in states with no similar policies.8

THE AMETHYST INITIATIVE ARGUMENT

The overall lack of progress in reducing drinking and related problems among college students nationally is of concern to many college officials.44 As of November 2009, presidents and chancellors of 135 colleges and universities have signed on to the Amethyst Initiative (http://www.amethystinitiative.org) calling for a public debate about lowering the minimum legal drinking age to 18 years.46 Specifically, they suggest that the current minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is not working to prevent youths from using alcohol and experiencing the negative consequences of drinking. The Amethyst Initiative suggests that the observed declines in drinking, traffic fatalities, and related harms since the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years became law are a result of other factors, such as improvements in motor vehicle safety, and not the change in the minimum legal drinking age. Furthermore, they contend that drinking among young adults aged 18–20 years is being driven underground by the minimum legal drinking age away from bars—where it is more carefully monitored—to private parties, which are less safe. Some college presidents have expressed concern that these unsafe drinking environments have contributed to an increase in alcohol poisoning deaths among youths and young adults. They also argue that young adults aged 18–20 years drink more responsibly in Western European countries where the minimum legal drinking age is lower.

Several researchers have examined these and other assertions regarding the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years in detail with available scientific evidence.46–48 Public health professionals should become familiar with these arguments and the evidence to advocate effective public policy.

RESEARCH ON THE MINIMUM LEGAL DRINKING AGE

The minimum legal drinking age has been perhaps the single most studied alcohol-control policy.12,46,48,49 Differences in laws among states and within states over time have allowed researchers to study the effect of this policy and come to some reliable conclusions. A review of 241 studies published between 1960 and 2000 that examined the effects of lowering or raising minimum drinking age laws identified 135 high-quality studies in terms of sampling, research design, and having an appropriate comparison group.12 Of the 79 quality studies that examined the relationship between the minimum legal drinking age and traffic crashes, 58% found fewer crashes associated with a higher minimum legal drinking age, whereas no study found fewer crashes associated with a lower minimum legal drinking age.12 Consistent with these findings, a higher minimum legal drinking age was associated with lower rates of alcohol consumption and other alcohol-related problems.12

Similar conclusions have been reached by subsequent studies that have accounted for other prevention policies and demographic shifts over time.13,50–52 Although 1 recent study cited by proponents of lowering the minimum legal drinking age concluded that the minimum legal drinking age does not save lives, the authors used methods that differed from those of other studies.53 The study compared states that adopted the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years early with those who adopted it later and concluded that later-adopting states (i.e., states that were compelled by the national policy) had no significant reduction in traffic fatalities. The analysis shows that early and late adopting states both had declines that were similar in magnitude, but these trends were not directly compared. They also examined overall fatalities, including those that did not involve alcohol, which would not be sensitive to changes in the minimum legal drinking age.

Another study of adults in the United States found that those who were legally able to purchase alcohol before age 21 years were more likely than those who could not to meet criteria for alcohol use disorder or another drug use disorder later in life.54 Despite uneven and sometimes lax enforcement, the best available evidence suggests that the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years has saved more than 800 lives annually among young adults aged 18–20 years in the United States.55,56

The minimum legal drinking age is not a single law or the sole policy designed to reduce heavy drinking and related harms among youths. It works in concert with other laws and alcohol-control policies. In addition to the effect of the primary restrictions on possessing and purchasing alcohol, other state laws that are designed to restrict underage drinking include zero tolerance laws for drinking and driving, administrative driver's license revocation, restrictions on possession of a false age identification, and mandatory training for servers on policies and procedures to prevent alcohol sales to minors and persons who are obviously intoxicated. In 1982, only 36 laws of this type were passed in all states. By 1997 the cumulative total grew to 204 and reached 245 in 2005.13

Recent research has examined the relative contribution of these policies and found that, in addition to the effect of the national minimum legal drinking age of 21 years, each of these policy restrictions is independently associated with lower levels of drinking and alcohol-involved fatalities among youths aged younger than 21 years.8,12,13,50–52 Drinking among youths and college students varies by state and is strongly associated with the level of drinking among adults and state alcohol control policies.33,57 States that had more alcohol control policies and laws to complement the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years had lower levels of drinking and related problems among underage youths.8,33,50,51

Private, off-campus residences and bars are the most frequently cited venues for heavy drinking among underage college students.8,58 However, licensed establishments are not the safe and controlled venues for drinking claimed by the Amethyst Initiative. Despite state-level restrictions on the purchase and consumption of alcohol for persons aged younger than 21 years, many college communities have local ordinances that allow persons aged 18–20 years entry into bars. Underage patrons are frequently able to obtain alcohol and drink heavily in off-campus bars, and heavy drinking is associated with disruptive and aggressive behavior and physical altercations in these venues.58,59 Studies in licensed establishments across multiple communities have shown that a high level of purchase attempts by underage and obviously intoxicated patrons are successful.60–63 Yet when establishment staff are trained and policies are enforced, illegal alcohol sales to these patrons are reduced.60,62

Countries with lower minimum legal drinking ages do not fare better. Contrary to the assertion of the Amethyst Initiative, heavy alcohol use among adolescents is a common problem across Europe. Frequent binge drinking among adolescents aged 15 to 16 years in many countries occurs at more than double the rate as in the United States.5,64,65 The European region has the highest overall consumption of alcohol among adults and the highest proportion of alcohol-attributable deaths in the world.65 Further, the experience with lowering the minimum legal drinking age in other countries is consistent with what occurred in the United States in the 1970s. In 1999 New Zealand lowered its national drinking age from 20 years to 18 years, resulting in significant increases in the occurrence of alcohol-involved emergency room admissions and traffic crashes among youths aged 15 to 19 years.66,67

One impetus for the reduction in the US minimum legal drinking age to 18 years in the 1970s was the institution of the Selective Service System to draft eligible males aged 18 to 25 years into compulsory military service during the Vietnam War. The rationale was that men old enough to serve in the military were old enough to drink alcohol. Recent research has pointed to the significant problem of binge drinking among active duty military personnel, particularly among personnel who are underage, and prompted concern over the negative impact drinking has on job performance and preparedness.68

Alcohol-related deaths among adolescents and young adults have increased in recent years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides the Alcohol-Related Disease Impact software to assess alcohol-attributable mortality trends with data from the National Vital Statistics System (https://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/ardi/HomePage.aspx). Table 1 shows that alcohol deaths rose among young adults aged 18 to 24 years for 2001 to 2006, with slightly higher increases among those aged 21–24 years. Most of the increase in deaths resulted from poisonings attributable to alcohol mixed with other substances, including opioids and other narcotics. However, alcohol poisoning deaths for young adults aged 18–20 years in this category did not increase and remain at about 9 or 10 deaths per year. Although a limitation of the ARDI system is that it assumes that the proportion of poisoning deaths over time that are attributable to alcohol is constant, these findings are consistent with an observed increase in the use of prescription drugs such as Vicodin and OxyContin among young adults.18

TABLE 1.

Trends in Alcohol-Attributable Mortality Among Young Adults Aged 18–24 Years: United States, 2001–2006

| No. of Alcohol-Attributable Deaths Among Young Adults Aged 18–20 Years |

No. of Alcohol-Attributable Deaths Among Young Adults Aged 21–24 Years |

|||||||||||||

| Alcohol-Attributable Deaths | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | % Change 2001 to 2006 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | % Change 2001 to 2006 |

| Chronic conditionsa | 56 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 51 | 51 | −9.3 | 281 | 264 | 271 | 274 | 253 | 254 | −9.8 |

| Acute conditions | ||||||||||||||

| Motor-vehicle traffic deaths | 971 | 1042 | 987 | 988 | 980 | 980 | 0.9 | 1890 | 2004 | 1939 | 1966 | 2042 | 2058 | 8.9 |

| Homicide | 597 | 604 | 613 | 603 | 646 | 648 | 8.5 | 1201 | 1230 | 1245 | 1198 | 1276 | 1282 | 6.7 |

| Suicide | 262 | 256 | 253 | 274 | 265 | 265 | 1.3 | 569 | 580 | 580 | 589 | 582 | 584 | 2.6 |

| Poisoning (alcohol) | 9 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 13.2 | 21 | 28 | 19 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 17.5 |

| Poisoning (not primarily alcohol) | 112 | 137 | 152 | 173 | 192 | 192 | 71.8 | 330 | 410 | 471 | 503 | 596 | 598 | 81.3 |

| Nonhighway deaths | 150 | 151 | 142 | 143 | 141 | 143 | −4.5 | 267 | 269 | 255 | 258 | 255 | 260 | −2.5 |

| Total | 2157 | 2251 | 2214 | 2247 | 2284 | 2289 | 6.1 | 4559 | 4784 | 4779 | 4812 | 5028 | 5060 | 11.0 |

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Alcohol-Related Disease Impact software (http://www.cdc.gov/Alcohol/ardi.htm).

Chronic conditions refer to persistent long-term medical conditions or diseases such as alcoholic myopathy, alcoholic liver disease, or fetal alcohol syndrome. The specific conditions considered are available at: https://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/ardi.

The public discussion about the minimum legal drinking age has focused on such arguments as whether the minimum legal drinking age was indeed responsible for observed declines in drinking and related problems. Less attention has been given to the central tenet of the Amethyst Initiative that a lower drinking age would lead to declines in drinking among college students and related problems. There is no scientific evidence to suggest that a lower minimum legal drinking age would create conditions for responsible drinking or would lead young adults aged 18–20 years to make healthy decisions about drinking.

EXPERTS ASSESS THE MINIMUM LEGAL DRINKING AGE

The minimum legal drinking age of 21 years has a strong legal basis and considerable political and empirical support.46 On the basis of the collective weight of evidence about the minimum legal drinking age, panels of experts and government agencies have consistently concluded that the national minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is effective public policy for reducing drinking and related problems and recommend closing loopholes in the law and strengthening enforcement. A report issued by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in 2002 recognized the distinct problem of drinking among college students and outlined a set of empirically based interventions to prevent and reduce drinking by college students.69 A prominent recommendation of this report was to increase enforcement of minimum drinking age laws.69 Other groups that have concluded that the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is an effective policy include the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Office of the US Surgeon General, and the Governors Highway Safety Association. The American Public Health Association has been vocal on this issue as well,70 and in 2008 members supported Policy Statement LB-08-02: “Maintaining and Enforcing the Age-21 Legal Drinking Age.”

REDUCING UNDERAGE DRINKING AND RELATED CONSEQUENCES

The Amethyst Initiative highlights the important and challenging problem of heavy drinking among college students. Despite considerable attention to this issue since the early 1990s, very little progress has been made in reducing drinking and binge drinking among students.18,20,21 Colleges and communities can do a number of things to reduce and prevent underage drinking. The NIAAA College Drinking Task Force recommendations included implementation of public information campaigns about, and enforcement of, laws to prevent alcohol-impaired driving, restrictions on alcohol retail outlets, increasing prices and excise taxes on alcoholic beverages, and implementing responsible beverage service policies at on- and off-campus venues.69 Few colleges have implemented these recommended policies and practices since the release of that report (T. F. Nelson, ScD, unpublished data, 2009). The Amethyst Initiative has not advocated, or taken a position on, any of these empirically based initiatives.46 It is difficult to imagine how the college presidents who may question the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years can enforce it on their campuses. Public health professionals can partner with colleges and help acquaint administrators with effective alcohol-control strategies, including policies such as the minimum legal drinking age, and counter the misleading messages issued by the Amethyst Initiative.

A major challenge to understanding and evaluating the best available interventions is the lack of consistent, ongoing surveillance research from a national perspective. The Monitoring the Future Study and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health collect data on young people of college age, but, because of their designs, these surveys lack the depth to evaluate changes at the college level that can reduce student drinking. The Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study has contributed to the understanding of these issues because it specifically studied students within colleges and assessed the college environments, including policy and programmatic initiatives.30 However, the most recent nationally representative study of the College Alcohol Study was conducted in 2001. A dedicated, ongoing survey is needed to understand whether progress is being made to reduce heavy drinking among college students.

The weight of the scientific evidence, evaluated by many experts and government agencies, demonstrates that the minimum legal drinking age of 21 years is effective public policy for reducing underage drinking and preventing the negative consequences that can result from underage drinking. The evidence suggests that making alcohol more available by reducing the minimum legal drinking age to 18 years will lead to an increase in drinking and related harms. The evidence shows instead that strengthening enforcement and establishing policies to support the existing minimum legal drinking age are effective approaches to lower alcohol-related morbidity and mortality among youths. Public health professionals can play an important leadership role to prevent and reduce the impact alcohol has on health by advocating effective, empirically supported alcohol-control policy initiatives at the local, state, and national level.

Acknowledgments

The Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study was generously supported by multiple grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

We thank M. Stahre of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Alcohol Team for analysis of the Alcohol-Related Disease Impact system.

References

- 1.Health, United States, 2008, With Special Feature on the Health of Young Adults, With Chartbook Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291(10):1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(37):866–870 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnie RJ, O'Connell ME. Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility Washington, DC: National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking, 2007 Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Edwards EM. Age at drinking onset, alcohol dependence, and their relation to drug use and dependence, driving under the influence of drugs, and motor-vehicle crash involvement because of drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2008;69(2):192–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner LA, White HR. Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Subst Use Misuse 2003;38(14):1983–2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Kuo M. Underage college students' drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies. Findings from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. J Am Coll Health 2002;50(5):223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. DHHS publication SMA 07-4293 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wechsler H, Sands ES. Minimum-age laws and youthful drinking: an introduction. : Wechsler H, Minimum-Drinking-Age Laws Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1980:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosher JF. The history of youthful-drinking laws: implications for current policy. : Wechsler H, Minimum-Drinking-Age Laws Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1980:11–38 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL. Effects of minimum drinking age laws: review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 2002;(14):206–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang JN. Statistical analysis of alcohol-related driving trends, 1982–2005. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; 2008. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration technical report DOT HS 810 942 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglass RL. The legal drinking age and traffic casualties: a special case of changing alcohol availability in a public health context. : Wechsler H, Minimum-Drinking-Age Laws Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1980:93–132 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagenaar AC. Research affects public policy: the case of the legal drinking age in the United States. Addiction 1993;88(suppl):75S–81S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. National Minimum Drinking Age Act, 23 USC §158 (1984)

- 17.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2007. Volume I: Secondary School Students Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. NIH publication 08-6418A [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2007. Volume II: College Students and Adults Ages 19-45 Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. NIH publication 08-6418B [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl 2009(16):12–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grucza RA, Norberg KE, Bierut LJ. Binge drinking among youths and young adults in the United States: 1979–2006. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48(7):692–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. J Am Coll Health 2002;50(5):203–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. J Stud Alcohol 2004;65(4):477–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. J Stud Alcohol Suppl 2002;(14):23–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slutske WS, Hunt-Carter EE, Nabors-Oberg RE, et al. Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? Evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. J Abnorm Psychol 2004;113(4):530–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight JR, Wechsler H, Kuo M, Seibring M, Weitzman ER, Schuckit MA. Alcohol abuse and dependence among U.S. college students. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63(3):263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Castillo S. Correlates of college student binge drinking. Am J Public Health 1995;85(7):921–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hingson R, Heeren T, Zakocs R, Winter M, Wechsler H. Age of first intoxication, heavy drinking, driving after drinking and risk of unintentional injury among US college students. J Stud Alcohol 2003;64(1):23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160(7):739–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addict Behav 2007;32(4):819–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2008;69(4):481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. A national survey of students at 140 campuses. JAMA 1994;272(21):1672–1677 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler H, Kuo M, Lee H, Dowdall GW. Environmental correlates of underage alcohol use and related problems of college students. Am J Prev Med 2000;19(1):24–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson TF, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Wechsler H. The state sets the rate: the relationship among state-specific college binge drinking, state binge drinking rates, and selected state alcohol control policies. Am J Public Health 2005;95(3):441–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight JR, Harris SK, Sherritt L, Kelley K, Van Hook S, Wechsler H. Heavy drinking and alcohol policy enforcement in a statewide public college system. J Stud Alcohol 2003;64(5):696–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H. Binge drinking in college: the impact of price, availability, and alcohol control policies. Contemp Econ Policy 1996;14:112–124 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo M, Wechsler H, Greenberg P, Lee H. The marketing of alcohol to college students: the role of low prices and special promotions. Am J Prev Med 2003;25(3):204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Nelson TF. Alcohol use and problems at colleges banning alcohol: results of a national survey. J Stud Alcohol 2001;62(2):133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Lee H. Drinking and driving among college students: the influence of alcohol-control policies. Am J Prev Med 2003;25(3):212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechsler H, Lee JE, Nelson TF, Lee H. Drinking levels, alcohol problems and secondhand effects in substance-free college residences: results of a national study. J Stud Alcohol 2001;62(1):23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weitzman ER, Folkman A, Folkman MP, Wechsler H. The relationship of alcohol outlet density to heavy and frequent drinking and drinking-related problems among college students at eight universities. Health Place 2003;9(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams J, Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H. Are there differential effects of price and policy on college students' drinking intensity? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2002. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w8702. Accessed February 16, 2010. NBER working paper 8702 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaloupka FJ, Wechsler H, Williams J. Are there differential effects of price and policy on college students' drinking intensity? Contemp Econ Policy 2005;23(1):78–90 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weitzman ER, Nelson TF, Wechsler H. Taking up binge drinking in college: the influences of person, social group, and environment. J Adolesc Health 2003;32(1):26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wechsler H, Seibring M, Liu IC, Ahl M. Colleges respond to student binge drinking: reducing student demand or limiting access. J Am Coll Health 2004;52(4):159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler H, Kelley K, Weitzman ER, SanGiovanni JP, Seibring M. What colleges are doing about student binge drinking. A survey of college administrators. J Am Coll Health 2000;48(5):219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toomey TL, Nelson TF, Lenk KM. The age 21 minimum legal drinking age: a case study linking past and current debates. Addiction 2009;104(12):1958–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fell JC. An Examination for the Criticisms of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age 21 Laws in the United States From a Traffic-Safety Perspective Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hingson RW. The legal drinking age and underage drinking in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163(7):598–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wechsler H. Minimum-Drinking-Age Laws: An Evaluation Lexington, MA: DC Heath and Company; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fell JC, Fisher DA, Voas RB, Blackman K, Tippetts AS. The impact of underage drinking laws on alcohol-related fatal crashes of young drivers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33(7):1208–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fell JC, Fisher DA, Voas RB, Blackman K, Tippetts AS. The relationship of underage drinking laws to reductions in drinking drivers in fatal crashes in the United States. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40(4):1430–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving. Am J Prev Med 2001;21(suppl 4):66–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miron JA, Tetelbaum E. Does the minimum legal drinking age save lives? Econ Inq 2009;47(2):317–336 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Norberg KE, Bierut LJ, Grucza RA. Long-term effects of minimum drinking age laws on past-year alcohol and drug use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33(12):2180–2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Traffic Safety Facts: Lives Saved in 2007 by Restraint Use and Minimum Drinking Age Laws. US Department of Transportation Washington, DC: National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kindelberger J. Calculating Lives Saved Due to Minimum Drinking Age Laws Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nelson DE, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Nelson HA. State alcohol-use estimates among youth and adults, 1993–2005. Am J Prev Med 2009;36(3):218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harford TC, Wechsler H, Seibring M. Attendance and alcohol use at parties and bars in college: a national survey of current drinkers. J Stud Alcohol 2002;63(6):726–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harford TC, Wechsler H, Muthen BO. Alcohol-related aggression and drinking at off-campus parties and bars: a national study of current drinkers in college. J Stud Alcohol 2003;64(5):704–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toomey TL, Erickson DJ, Lenk KM, Kilian GR, Perry CL, Wagenaar AC. A randomized trial to evaluate a management training program to prevent illegal alcohol sales. Addiction 2008;103(3):405–413, discussion 414–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lenk KM, Toomey TL, Erickson DJ. Propensity of alcohol establishments to sell to obviously intoxicated patrons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006;30(7):1194–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Erickson DJ. Preventing youth access to alcohol: outcomes from a multi-community time-series trial. Addiction 2005;100(3):335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toomey TL, Wagenaar AC, Erickson DJ, Fletcher LA, Patrek W, Lenk KM. Illegal alcohol sales to obviously intoxicated patrons at licensed establishments. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28(5):769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlstrom S, et al. The 2007 ESPAD Report: Substance Use Among Students in 35 European Countries Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009;373(9682):2223–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kypri K, Voas RB, Langley JD, et al. Minimum purchasing age for alcohol and traffic crash injuries among 15- to 19-year-olds in New Zealand. Am J Public Health 2006;96(1):126–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Everitt R, Jones P. Changing the minimum legal drinking age—its effect on a central city emergency department. N Z Med J 2002;115(1146):9–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS. Binge drinking among U.S. active-duty military personnel. Am J Prev Med 2009;36(3):208–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism A Call to Action: Changing the Culture of Drinking at U.S. Colleges Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Degutis L. Choose accountability: keep the legal US drinking age at 21. The Nation's Health October 1, 2008:3 [Google Scholar]