Abstract

Most US jails and prisons do not provide condoms to prisoners because of concerns about possible negative consequences. Since 1989, the jail system of San Francisco, California, has provided condoms to male prisoners through 1-on-1 counseling sessions. Given the limitations of this approach, we installed, stocked, and monitored a free condom-dispensing machine in a jail to examine the feasibility of this method of providing condoms to jail prisoners. After the machine was installed, we observed increases in prisoners' awareness of programmatic access to condoms and in their likelihood of having obtained condoms. Particularly large increases in condom uptake were reported among those in high-risk groups. Sexual activity did not increase, custody operations were not impeded, and staff acceptance of condom access for prisoners increased.

KEY FINDINGS

▪Prisoners' awareness of programmatic access to condoms and their likelihood of having obtained condoms increased after a free condom-dispensing machine was installed in the jail where they were incarcerated.

▪Prisoners who were gay, female/transgender/other gender, or previously diagnosed with HIV were more likely to have obtained condoms than prisoners who were heterosexual, male, or HIV-negative.

▪Sexual activity did not increase.

▪Custody operations were not impeded, and custody staff acceptance of condom access for prisoners improved.

Jails are important venues for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. The prevalence of HIV/AIDS is estimated to be about 4 times higher among prisoners than among the general US population,1,2 and many attributes that put individuals at risk for incarceration also increase HIV risk. Substantial evidence exists to suggest that high-risk behavior and transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections occurduring incarceration.3–5 Because of high turnover and recidivism rates among jail prisoners, disease prevention among prisoners also has implications for the health of the larger community.

Since 1989, the San Francisco, California, jail system has allowed prisoners to obtain condoms (1 at a time) in individually scheduled health-education sessions with staff from the Forensic AIDS Project (FAP) of the county health department. FAP staff have not formally tracked condom uptake among San Francisco jail prisoners, but they have anecdotally reported very low uptake (K. M. Klein, director, Forensic AIDS Project, oral communication, August 2006).

Condom-dispensing machines are used in jails and prisons abroad,6 but before the current study, no US jail or prison facility had used this method to provide condoms to prisoners. To examine the feasibility of applying this method in San Francisco jails, we installed, stocked, and monitored a free condom-dispensing machine in 1 of the city's jails.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

The Novel Condom Access Program for San Francisco County Jail Prisoners was a collaboration between the Center for Health Justice (a community-based organization focused on HIV prevention and treatment among prisoners in California), the San Francisco Sheriff's Department, FAP, and the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies of the University of California, San Francisco, which funded the evaluation. We installed, stocked, and monitored 1 condom-dispensing machine in a gymnasium facility to which 800 prisoners had weekly access.

The machine, purchased from an online vendor for $200, was stocked with individually wrapped Lifestyles brand vending condoms that cost about 22 cents each but were dispensed at no charge. Before installing the machine, program staff briefed custody staff and prisoners in the affected jail units about the program's operation and purpose.

The C&G Manufacturing Series 1000 condom-dispensing machine used during the pilot study.

Between April 17, 2007, and August 17, 2007, a Center for Health Justice or FAP staff member regularly restocked the machine, escorted by custody staff. After the study period the machine remained in operation. San Francisco jail prisoners now have access to FAP-supplied condoms through 2 methods: individual health-education sessions and the condom-dispensing machine.

EVALUATION

We tracked the number of condoms dispensed, and we assessed the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of both prisoners and staff. We conducted quantitative preintervention and postintervention surveys and face-to-face qualitative postintervention interviews with a convenience sample of prisoners. We used the Pearson χ2 test and the Fisher exact test (when recommended because of small sample sizes) to estimate P values for differences between the preintervention and postintervention samples. We also conducted qualitative interviews with 5 sheriff's department staffers who were responsible for the affected jail areas. Prisoner participants were recruited by announcing the voluntary study in housing units, during recreation periods, and during a transgender health class. The research team selected staff participants on the basis of their relationship to the operation of the affected housing areas.

Between April 17, 2007, and August 17, 2007, the machine was checked and restocked 15 times, or approximately once per week. Condom-dispensing rates were tracked by counting the number restocked each time. The machine dispensed a total of 1331condoms (mean = 89 per week). During the first 2 weeks, a total of 413 condoms were dispensed. After that, the number dispensed declined to a mean of 76 per week.

Prisoner Responses

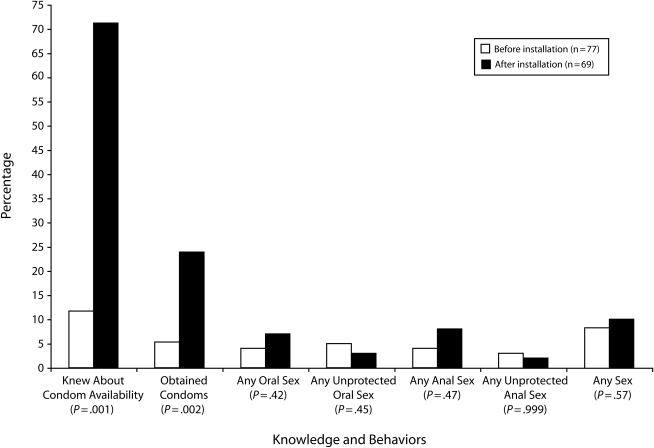

Seventy-seven prisoners were surveyed before machine installation, and 69 were surveyed after the 4-month evaluation period. Their characteristics were similar to the demographics of the larger jail population; with the exception of interviewing fewer Hispanics and younger people at postintervention, the 2 samples differed little between time points (Table 1). Awareness of condom availability and uptake increased overall following machine installation; sexual activity did not (Figure 1). Postintervention awareness increased among all groups. Respondents at increased risk for HIV infection or transmission—transgender people, those who self-reported as HIV-positive, and those whose self-identified as anything other than heterosexual or straight (the other sexual orientation options were homosexual or gay, bisexual, or other)—reported higher program utilization than those who self-identified as heterosexual or HIV-negative.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Prisoner Participants in a Pilot Study of the First Condom-Dispensing Machine in a US Jail: San Francisco, CA, 2007

| Preintervention (N = 77), No. (%) | Postintervention (N = 69), No. (%) | Pa | |

| Age, y | .076 | ||

| 18–34 | 27 (35) | 13 (19) | |

| 35–44 | 26 (34) | 26 (38) | |

| ≥45 | 24 (31) | 30 (44) | |

| Race/ethnicity | .015 | ||

| Black | 41 (57) | 33 (53) | |

| White | 15 (21) | 22 (35) | |

| Hispanic | 9 (12) | 0 | |

| Asian | 8 (11) | 7 (11) | |

| Gender | .985 | ||

| Men | 68 (88) | 61 (88) | |

| Transgender/women/other | 9 (12) | 8 (12) | |

| Self-identified sexual orientation | .778 | ||

| Heterosexual | 64 (86) | 58 (88) | |

| Homosexual/bisexual/other | 11 (15) | 9 (13) | |

| No. of incarcerations | .465 | ||

| 1 | 6 (8) | 8 (12) | |

| ≥2 | 68 (92) | 58 (88) | |

| Current incarceration length, d | .688 | ||

| 1–14 | 5 (6) | 4 (6) | |

| 15–60 | 10 (13) | 15 (23) | |

| ≥61 | 62 (81) | 49 (73) | |

| HIV statusb | .407 | ||

| Positive | 10 (14) | 6 (10) | |

| Negative | 60 (85) | 54 (90) | |

| Education | .290 | ||

| Less than high school | 12 (16) | 5 (8) | |

| High school or GED | 42 (55) | 41 (61) | |

| Some college or degree | 23 (30) | 22 (33) |

Note. GED = general equivalency degree.

P value for difference across the subcategories in each group.

Self-reported HIV status.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of jail prisoner participants self-reported knowledge of condom availability, obtainment of condoms, and engagement in sexual behaviors, before and after condom machine installation: San Francisco, CA, 2007.

In the qualitative interviews (n = 9), many prisoners reported that sex in jail occurs mostly among the transgender and openly gay prisoners, and most respondents supported condom access. Some, however, said they believed that prisoners were more likely to have sex if condoms were available, because then “[sex] can be safe.”

Interviewees reported little or no embarrassment associated with accessing the machine themselves and few or no negative thoughts about prisoners who did. One prisoner said, “If people see me [take a condom] I don't care… . Everybody takes them.” Another said, “That person is being protected and don't want to catch nothing and don't want to give nothing.”

Staff Responses

We conducted pre- and postintervention interviews with 2 custody staff members and 3 administrative staff members (1 custody staff member was unavailable for the postintervention interview). In the preintervention interview, 3 staffers expressed reservations about providing prisoners condoms. Those with regular prisoner contact were primarily concerned about discipline and operational issues, and higher-level administrators were concerned that condom access would send a “mixed message,” because sex is illegal in jail. At postintervention, all said they approved of increased prisoner access to condoms.

NEXT STEPS

Policymakers have used the results of this study to support the expansion of in-custody condom distribution via machine dispensersin California. Shortly after the study's conclusion, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger directed state prison administrators to determine the “risks and viability” of giving state prisoners access to condoms through a pilot program in 1 state prison facility.7 State prison officials visited the San Francisco jails, viewed the machine installed for the study, and discussed implementation with administrators. A 12-month pilot program for the state prison system installed condom machines in Solano State Prison in November 2008, with findings anticipated in late 2010. This success aside, the controversial nature of these programs means that widespread political support seems unlikely in the short term.

Despite this pilot study's potential limitations, such as selective participation or bias in participant responses, our findings provide support for the overall acceptability and viability of this method of prisoner condom access, which is novel in the United States. We also found that installation of the condom machine was associated with increases in awareness and utilization of condoms, compared with the existing condom-distribution program, which required greater initiative from the prisoner. Finally, our findings indicate that pilot programs that test whether condoms present security challenges within particular custody settings have the potential to shift custody and administrative staff attitudes in favor of this important public health measure.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies of the University of California, San Francisco, and by the California HIV Research Program (grant HP08-LA-001).

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and cooperation of San Francisco Sheriff Michael Hennessey and the staff of County Jail 4, as well as Kate Monico Klein, director of the Forensic AIDS Project, and her staff.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the committee on human research of the University of California, San Francisco. Approval for secondary analysis was received from the institutional review boards of Charles Drew University and the University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- 1.Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2004 Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Dept of Justice; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008;57(39):1073–1076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV transmission among male inmates in a state prison system—Georgia, 1992–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55(15):421–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brewer TF, Vlahov D, Taylor E, Hall D, Munoz A, Polk BF. Transmission of HIV-1 within a statewide prison system. AIDS 1988;2(5):363–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe MI, Xu F, Patel P, et al. An outbreak of syphilis in Alabama prisons: correctional health policy and communicable disease control. Am J Public Health 2001;91(8):1220–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Policy Brief: Reduction of HIV Transmission in Prisons Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarzenegger A. Governor's veto: Inmate and Community Public Health and Safety Act. Cal AB 1334 2007 [Google Scholar]