Abstract

Objectives. We calculated the percentage of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) attributable to overweight and obesity.

Methods. We analyzed 2004 through 2006 data from 7 states using the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System linked to revised 2003 birth certificate information. We used logistic regression to estimate the magnitude of the association between prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) and GDM and calculated the percentage of GDM attributable to overweight and obesity.

Results. GDM prevalence rates by BMI category were as follows: underweight (13–18.4 kg/m2), 0.7%; normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), 2.3%; overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), 4.8%; obese (30–34.9 kg/m2), 5.5%; and extremely obese (35–64.9 kg/m2), 11.5%. Percentages of GDM attributable to overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity were 15.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 8.6, 22.2), 9.7% (95% CI = 5.2, 14.3), and 21.1% (CI = 15.2, 26.9), respectively. The overall population-attributable fraction was 46.2% (95% CI = 36.1, 56.3).

Conclusions. If all overweight and obese women (BMI of 25 kg/m2 or above) had a GDM risk equal to that of normal-weight women, nearly half of GDM cases could be prevented. Public health efforts to reduce prepregnancy BMI by promoting physical activity and healthy eating among women of reproductive age should be intensified.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as carbohydrate intolerance leading to hyperglycemia with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.1 GDM affects 1% to 14% of pregnancies, depending on the population studied and the diagnostic tests used.1,2 It has been associated with maternal, fetal, and infant complications, including infant macrosomia and birth trauma, infant hypoglycemia, cesarean section, and increased medical costs.3–7 Although some women with diagnosed GDM will have persistent abnormal glycemia, most women will revert to normal carbohydrate metabolism after delivery.8 However, women with a history of GDM remain at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus in the future.9 GDM and type 2 diabetes share many common risk factors, including overweight and obesity, and GDM is considered by many to be a precursor of type 2 diabetes.10

In addition, evidence suggests that the incidence of GDM increased in the 1990s.11,12 This rise, which was concurrent with the growing prevalence of prepregnancy obesity (a 69.3% increase between 1993–1994 and 2002–2003)13 and increases in type 2 diabetes in the general population (a 48.8% increase from 1994 through 2002),14 was independent of other risk factors such as maternal age and parity.13 Although GDM risk increases substantially with increasing prepregnancy body mass index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared),15 the percentage of GDM specifically attributable to overweight and obesity is currently unknown.

Population-based risk estimates are needed to calculate the percentage of GDM cases that could potentially be prevented if all women who are overweight or obese had a GDM risk equivalent to that of women of normal weight. We sought to calculate the percentage of pregnancies affected by GDM and the percentage of GDM attributable to overweight and obesity as a means of better understanding the potential effects of weight management on GDM prevalence.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), an ongoing population-based surveillance system that collects information on self-reported maternal characteristics before, during, and after pregnancy in participating states. Each month, a stratified systematic sample of approximately 150 mothers is selected from the birth certificate records of each state. To participate in PRAMS, women must be state residents who have recently delivered a live-born infant, typically in the preceding 3 or 4 months.

A self-administered, 14-page questionnaire is mailed to each eligible mother. If the mother fails to respond, a second or third questionnaire is sent to her. If there is no response to these additional mailings, attempts are made to reach the mother for a telephone interview. Each mother's self-reported survey data are linked back to her child's birth certificate record; only selected birth certificate variables are included in the final PRAMS data set. Currently, 37 states, New York City, and the Yankton Sioux Tribe in South Dakota participate in PRAMS.

We selected states that had an annual weighted PRAMS response rate of 70% or higher and had implemented the 2003 revised US birth certificate, the latter because this version of the birth certificate includes information on GDM separate from preexisting diabetes and does not combine the 2 conditions. Our study sample included 23 904 women who were surveyed in 2004, 2005, or 2006 in 7 states: Florida (2004–2005), Nebraska (2005–2006), New York (excluding New York City; 2004–2006), Ohio (2006), South Carolina (2004–2006), Vermont (2004–2006), and Washington (2004–2006). We increased the sampling weights of records from states with fewer years of data so that the sum of each state's weights represented the same number of years.

Maternal Characteristics

We used birth certificate information to analyze data on maternal characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, parity, smoking status, prepregnancy weight and height, and GDM diagnosis. We did not obtain information on preexisting diabetes from the birth certificates because this information is not part of the final PRAMS data set. Maternal race/ethnicity was self-reported and categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or other (Alaska Natives, American Indians, Asian Americans, or individuals of other racial/ethnic backgrounds). In Vermont, all women with the exception of non-Hispanic Whites are combined as “other” because of the small number of women in other racial/ethnic groups residing in Vermont; thus, we included only information for non-Hispanic White women in our analyses of Vermont data.

Data analyzed from the PRAMS questionnaire included prenatal enrollment in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Medicaid status; smoking status; prepregnancy weight and height; and whether the woman had preexisting diabetes. Women who indicated on either the birth certificate or the PRAMS questionnaire that they had smoked during the final 3 months of their pregnancy were classified as smokers.

When available, we used prepregnancy weight and height data from birth certificates (such data were available in 92% of cases) to calculate prepregnancy BMI; we used information from PRAMS if birth certificate data were missing. Our reason for using birth certificate data in these calculations was that, in PRAMS, prepregnancy height and weight are collected typically 3 or 4 months after delivery. We excluded BMI values below the 0.01st percentile and above the 99.99th percentile (less than 13 kg/m2 and more than 64.9 kg/m2, respectively). Thus, on the basis of our exclusions and the BMI categories defined by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, we defined underweight as 13 to 18.4 kg/m2, normal weight as 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, overweight as 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, obese as 30 to 34.9 kg/m2, and extremely obese as 35 to 64.9 kg/m2.

Data Analysis

We excluded the following women from the analysis: those who reported on PRAMS that they had preexisting diabetes (these women by definition could not develop GDM), those for whom information about prepregnancy weight or height or information about GDM was missing, and those in Vermont who were of a racial/ethnic group other than non-Hispanic White. After these exclusions, data on 22 767 women (95% of the total sample) were available for the final analysis.

We estimated the prevalence and standard errors of various demographic characteristics by state and calculated the prevalence of GDM by category for each characteristic. Using sample-weighted multivariate logistic regression, we estimated the independent contributions of BMI to GDM risk via aggregated data from the 7 states in our study. We assessed potential confounding for each demographic characteristic and considered a covariate to be potential confounder if its inclusion in the regression models changed the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) by 10% or more. Using the logistic regression results, we computed relative risks (RRs) and their confidence intervals (CIs) according to methods described by Flanders and Rhodes.16

Finally, employing methods described by Graubard and Fears,17 we used the logistic regression results to estimate the population-attributable fraction (PAF) and its CI for each overweight or obese BMI category and for all overweight and obese categories combined. We interpreted each PAF estimate to be the reduction in disease prevalence that would be expected to occur if all women in the overweight or obese BMI categories had a GDM risk equivalent to that of women in the normal BMI category, assuming that the risk for GDM among those with a low or normal BMI remained unchanged.18

We also used locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) to estimate the probability of GDM as a continuous function of BMI. In this method, the smoothed value of the function at each data point is computed from a weighted regression fit to neighboring points. Neighboring points that are closer to the point at which the smoothing occurs are weighted more heavily.19,20

In all of the analyses other than those involving LOESS, the data were weighted to adjust for survey design, months of data sampling for the state, nonresponse, and the extent to which some individuals in the target population were not included in the sampled population. We used Sudaan version 10.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to fit the logistic models and compute ORs and their standard errors, S-Plus version 7.020 to perform the LOESS analyses, and SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all other computations.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the PRAMS population in each of the 7 states are described in Table 1. The overall GDM prevalence was 4.0% (SE = 0.2), with a range from 3.1% (SE = 0.4) in Florida to 5.0% (SE = 0.7) in Ohio (Table 1). For all states combined, GDM prevalence estimates by BMI category were as follows: underweight, 0.7% (SE = 0.3); normal weight, 2.3% (SE = 0.3); overweight, 4.8% (SE = 0.5); obese, 5.5% (SE = 0.7); and extremely obese, 11.5% (SE = 1.3; Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Sample-Weighted Demographic Characteristics: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 7 US States, 2004–2006

| Maternal Characteristic | Total(2004–2006), % (SE) | Florida(2004–2005), % (SE) | Nebraska(2005–2006),% (SE) | New Yorka(2004–2006), % (SE) | Ohio(2006), % (SE) | South Carolina(2004–2006), % (SE) | Vermont(2004–2006), % (SE) | Washington(2004–2006), % (SE) |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| < 20 | 10.4 (0.3) | 11.0 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.5) | 7.5 (0.7) | 12.0 (1.2) | 13.3 (0.9) | 7.1 (0.5) | 9.0 (0.6) |

| 20–34 | 74.7 (0.5) | 74.9 (0.8) | 80.2 (0.8) | 70.7 (1.1) | 75.5 (1.5) | 76.2 (1.1) | 75.7 (0.8) | 76.2 (0.9) |

| ≥ 35 | 14.9 (0.4) | 14.1 (0.8) | 12.4 (0.7) | 21.7 (1.0) | 12.5 (1.1) | 10.5 (0.8) | 17.1 (0.7) | 14.8 (0.7) |

| Education, y | ||||||||

| < 12 | 18.2 (0.5) | 20.4 (0.8) | 14.9 (0.6) | 16.2 (1.0) | 15.7 (1.3) | 23.0 (1.2) | 9.3 (0.6) | 17.4 (0.7) |

| 12 | 27.9 (0.6) | 32.4 (1.0) | 21.1 (0.9) | 23.1 (1.0) | 28.4 (1.6) | 26.0 (1.2) | 32.1 (0.9) | 24.5 (0.9) |

| > 12 | 53.9 (0.6) | 47.2 (1.1) | 64.1 (0.9) | 60.7 (1.2) | 55.9 (1.7) | 50.9 (1.3) | 58.6 (0.9) | 58.1 (1.0) |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 15.6 (0.4) | 27.1 (1.0) | 14.0 (0.1) | 13.1 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.7) | 7.4 (0.7) | NA | 17.5 (0.1) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 63.9 (0.5) | 48.2 (1.0) | 75.5 (0.2) | 74.5 (1.1) | 77.3 (1.0) | 58.3 (1.3) | 100.0 | 64.9 (0.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 15.2 (0.2) | 20.1 (0.5) | 5.5 (0.1) | 7.9 (0.7) | 14.8 (0.2) | 31.9 (1.3) | NA | 3.2 (0.1) |

| Other | 5.3 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.5) | 4.9 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.4) | NA | 14.4 (0.4) |

| Married | ||||||||

| Yes | 61.9 (0.6) | 58.2 (1.0) | 71.1 (0.9) | 67.0 (1.2) | 60.1 (1.7) | 56.9 (1.3) | 68.8 (0.9) | 69.6 (0.9) |

| No | 38.1 (0.6) | 41.8 (1.0) | 28.9 (0.9) | 33.0 (1.2) | 39.9 (1.7) | 43.1 (1.3) | 31.2 (0.9) | 30.4 (0.9) |

| Medicaid recipient | ||||||||

| Yes | 45.9 (0.6) | 51.2 (1.1) | 40.9 (1.0) | 35.5 (1.2) | 41.7 (1.7) | 58.1 (1.3) | 42.1 (0.9) | 49.2 (1.0) |

| No | 54.1 (0.6) | 48.8 (1.1) | 59.1 (1.0) | 64.5 (1.2) | 58.3 (1.7) | 41.9 (1.3) | 57.9 (0.9) | 50.8 (1.0) |

| WIC recipient | ||||||||

| Yes | 55.7 (0.6) | 52.1 (1.1) | 63.3 (0.9) | 62.4 (1.2) | 58.1 (1.7) | 45.0 (1.3) | 59.2 (0.9) | 55.9 (1.0) |

| No | 44.3 (0.6) | 47.9 (1.1) | 36.7 (0.9) | 37.6 (1.2) | 41.9 (1.7) | 55.0 (1.3) | 40.8 (0.9) | 44.1 (1.0) |

| Parity | ||||||||

| 0 | 42.1 (0.6) | 43.3 (1.1) | 36.7 (1.0) | 41.6 (1.2) | 41.0 (1.7) | 42.4 (1.3) | 44.8 (0.9) | 42.9 (1.0) |

| 1–2 | 47.9 (0.6) | 46.8 (1.1) | 50.8 (1.1) | 49.1 (1.2) | 47.3 (1.8) | 50.3 (1.3) | 48.2 (0.9) | 47.0 (1.1) |

| > 2 | 10.0 (0.4) | 9.8 (0.7) | 12.5 (0.7) | 9.3 (0.7) | 11.7 (1.1) | 7.3 (0.7) | 6.9 (0.5) | 10.1 (0.6) |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Smokerc | 13.4 (0.4) | 9.1 (0.7) | 15.8 (0.8) | 15.5 (0.9) | 17.4 (1.3) | 15.6 (1.0) | 18.3 (0.7) | 11.5 (0.7) |

| Nonsmoker | 86.6 (0.4) | 90.9 (0.7) | 84.2 (0.8) | 84.5 (0.9) | 82.6 (1.3) | 84.4 (1.0) | 81.7 (0.7) | 88.5 (0.7) |

| BMI category, kg/m2 | ||||||||

| Underweight (13–18.4) | 4.8 (0.3) | 6.1 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.3) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 50.3 (0.6) | 53.8 (1.1) | 50.3 (1.1) | 50.4 (1.2) | 48.0 (1.7) | 44.1 (1.3) | 50.5 (0.9) | 49.0 (1.0) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 23.8 (0.5) | 22.1 (0.9) | 24.5 (0.9) | 24.3 (1.0) | 24.2 (1.5) | 25.3 (1.2) | 24.1 (0.8) | 26.4 (0.9) |

| Obese (30–34.9) | 11.9 (0.4) | 10.5 (0.7) | 13.0 (0.7) | 12.3 (0.8) | 12.3 (1.2) | 14.7 (0.9) | 12.2 (0.6) | 12.0 (0.7) |

| Extremely obese (35–64.9) | 9.2 (0.4) | 7.6 (0.6) | 7.9 (0.6) | 9.7 (0.7) | 10.4 (1.0) | 11.2 (0.8) | 10.1 (0.6) | 9.5 (0.6) |

| GDM | ||||||||

| Yes | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 5.0 (0.7) | 4.9 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.4) |

| No | 96.0 (0.2) | 96.9 (0.4) | 96.0 (0.4) | 96.2 (0.4) | 95.0 (0.7) | 95.1 (0.6) | 96.6 (0.3) | 95.2 (0.4) |

Note. BMI = body mass index; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; NA = not applicable; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. The total sample size was N = 22767; for Florida, n = 4053; for Nebraska, n = 3411; for New York, n = 2744; for Ohio, n = 1497; for South Carolina, n = 3848; for Vermont, n = 3097; for Washington, n = 4117. Overall and state sample sizes are unweighted.

Excludes New York City.

Only non-Hispanic White women were included in analyses of Vermont data.

Defined as smoking during the final 3 months of pregnancy (self-reported in PRAMS) or during the third trimester (reported on birth certificates).

TABLE 2.

Sample-Weighted Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) Prevalence, by Demographic Characteristics: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 7 US States, 2004–2006

| Maternal Characteristic | GDM Prevalence, % (SE) |

| Overall | 4.0 (0.2) |

| Age, y | |

| < 20 | 1.0 (0.3) |

| 20–34 | 3.6 (0.3) |

| ≥ 35 | 8.4 (0.9) |

| Education, y | |

| < 12 | 2.8 (0.4) |

| 12 | 3.9 (0.5) |

| > 12 | 4.5 (0.3) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |

| Hispanic | 4.4 (0.6) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 4.0 (0.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3.6 (0.4) |

| Other | 5.4 (1.0) |

| Married | |

| Yes | 4.6 (0.3) |

| No | 3.1 (0.3) |

| Medicaid recipient | |

| Yes | 3.4 (0.3) |

| No | 4.6 (0.4) |

| WIC recipient | |

| Yes | 4.3 (0.4) |

| No | 3.7 (0.3) |

| Parity | |

| 0 | 3.0 (0.3) |

| 1–2 | 4.8 (0.4) |

| > 2 | 5.0 (0.9) |

| Smoking status | |

| Smokerb | 3.7 (0.6) |

| Nonsmoker | 4.1 (0.3) |

| BMI category, kg/m2 | |

| Underweight (13–18.4) | 0.7 (0.3) |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 2.3 (0.3) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 4.8 (0.5) |

| Obese (30–34.9) | 5.5 (0.7) |

| Extremely obese (35–64.9) | 11.5 (1.4) |

Note. BMI = body mass index; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Only non-Hispanic White women were included in analyses of Vermont data.

Defined as smoking during the final 3 months of pregnancy (self-reported in PRAMS) or during the third trimester (reported on birth certificates).

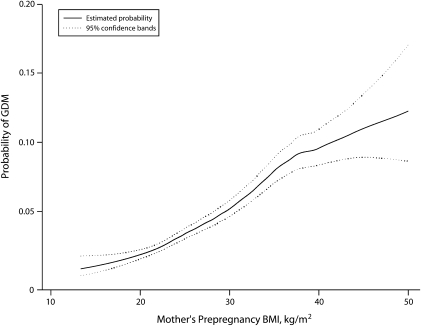

In addition, we found that 0.9% (SE = 0.4) of women with gestational diabetes were underweight, 28.4% (SE = 2.8) were of normal weight, 28.5% (SE = 2.7) were overweight, 16.2% (SE = 2.1) were obese, and 26.0% (SE = 2.7) were extremely obese. The probability of GDM increased with increasing BMI, although the confidence bands became quite wide when BMIs exceeded 40 kg/m2 (Figure 1). There was no clear BMI threshold below which a dose–response relationship was not evident.

FIGURE 1.

Unweighted probability of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), by mother's prepregnancy body mass index (BMI): Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 7 US states, 2004–2006.

Note. BMI is defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Because none of the potential confounders changed ORs by 10% or more, we included in our adjusted model covariates that have been found in the literature to be associated with both the exposure (BMI) and the outcome (GDM). When the normal-weight BMI category was used as a reference group, we found that the unadjusted RRs of developing GDM were 0.3 (95% CI = 0.1, 0.7) for underweight women, 2.1 (95% CI = 1.6, 2.9) for overweight women, 2.4 (95% CI = 1.7, 3.4) for obese women, and 5.0 (95% CI = 3.6, 6.9) for extremely obese women. RRs did not change after adjustment for maternal age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and parity (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sample-Weighted Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) Risk Data: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, 7 US States, 2004–2006

| RR (95% CI) |

PAFb (95% CI) |

|||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Underweight (13–18.4 kg/m2) | 0.32 (0.14, 0.75) | 0.38 (0.16, 0.89) | … | … |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2; Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | … | … |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 2.12 (1.55, 2.90) | 2.17 (1.58, 2.97) | 15.1 (8.3, 21.9) | 15.4 (8.6, 22.2) |

| Obese (30–34.9 kg/m2) | 2.41 (1.71, 3.41) | 2.51 (1.76, 3.56) | 9.5 (4.9, 14.0) | 9.7 (5.2, 14.3) |

| Extremely obese (35–64.9 kg/m2) | 5.02 (3.64, 6.93) | 5.03 (3.64, 6.95) | 20.8 (15.0, 26.6) | 21.1 (15.2, 26.9) |

| All BMI categories above normal weight | … | … | 45.4 (35.3, 55.5) | 46.2 (36.1, 56.3) |

Note. BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; PAF = population-attributable fraction; RR = relative risk. The sample size used for unadjusted RR was n = 22 767; for adjusted RR, n = 22 200.

Adjusted models included covariates for maternal age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and parity.

We interpreted each PAF estimate to be the reduction in disease prevalence that would be expected to occur if all women in the overweight or obese BMI categories had a GDM risk equivalent to that of women in the normal BMI category, assuming that the risk for GDM among those with a low or normal BMI remained unchanged.

The overall adjusted PAF due to overweight and obesity was 46.2% (95% CI = 36.1, 56.3; Table 2). Adjusted percentages of GDM individually attributable to overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity were 15.4% (95% CI = 8.6, 22.2), 9.7% (95% CI = 5.2, 14.3), and 21.1% (95% CI = 15.2, 26.9), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our results show an increased risk of GDM associated with increasing BMI. The overall PAF due to overweight and obesity was 46.2%. In other words, if all women with BMIs of 25 or above had a GDM risk equal to that of women in the normal BMI category, nearly half of GDM cases potentially could be prevented. In addition, we found that more than 70% of all women with GDM had a BMI of 25 or higher, whereas approximately a quarter had a normal BMI.

High maternal BMIs have been consistently associated with an increased risk of GDM in the literature.15,21 In a meta-analysis estimating the magnitude of GDM risk among women with high prepregnancy BMIs, Chu et al. found that GDM risk increases substantially with increasing prepregnancy BMI.15 Their results showed that, relative to women of normal weight, the unadjusted ORs for developing GDM were 2.14 (95% CI = 1.82, 2.53) among overweight women, 3.56 (95% CI = 3.05, 4.21) among obese women, and 8.56 (95% CI = 5.07, 16.04) among extremely obese women.14 Moreover, similar to our findings, a dose–response relationship between increasing BMI and type 2 diabetes has been described in the general population, even within the normal BMI category.22–24

Although women with GDM are at increased risk for type 2 diabetes,9 evidence strongly suggests that type 2 diabetes is preventable in this population. Several randomized trials have demonstrated that weight loss and increased physical activity reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes in individuals at high risk, including women with a history of GDM.25–27 Similarly, evidence suggests that GDM risk is reduced in women who engage in high levels of physical activity28 and consume high-fiber diets.29 Therefore, to the extent that prepregnancy overweight and obesity cause GDM, reducing prepregnancy weight in these women should reduce diabetes-related adverse pregnancy outcomes. Sustaining this weight loss beyond pregnancy should reduce women's future risk for type 2 diabetes.30

Limitations

To our knowledge, our study provides the first population-based estimates of the contribution of overweight and obesity to GDM. However, the study involves some limitations. Prepregnancy weight is self-reported in PRAMS and is likely to be self-reported on birth certificates; estimates of obesity prevalence based on self-reported weight tend to be lower than those based on measured data.31 Therefore, we may have underestimated the prevalence of prepregnancy overweight and obesity, which could have resulted in an underestimation of the contribution of overweight and obesity to the PAF assuming that the BMI misclassification was nondifferential.

In addition, because PRAMS collects data only on women who have delivered a live-born infant, our analysis did not include women whose pregnancies ended in a miscarriage, fetal death, or stillbirth. However, GDM typically develops in the late second or early third trimester of pregnancy, and only a small proportion of women (6.3 per 1000 women) experience fetal loss after 20 weeks. Therefore, our estimates of GDM prevalence should not have been substantially affected by the restriction of our analysis to live births.

Our data also may not be generalizable to states not included in our analyses. For example, GDM prevalence has been shown to vary by racial/ethnic group. Nineteen percent of all US live births were represented in our analyses, and non-Hispanic White women were overrepresented in our study (64% of the mothers included in our analysis were non-Hispanic White, as compared with 55% in the total US population of mothers delivering a live-born infant).32 Moreover, prepregnancy obesity varies by state, ranging from 13.9% to 25.1% in 26 PRAMS states that represented 47% of all live births in the United States during 2004–2005.33 This variation, in part, may explain the differences in the prevalence of GDM across states. Therefore, a national estimate of the contribution of prepregnancy weight to GDM risk may be different from our estimate.

Furthermore, although the association between BMI and GDM risk appears to vary according to race/ethnicity, we were not able to calculate PAFs for specific racial/ethnic groups as a result of our small poststratification sample sizes. Large databases are needed to conduct more in-depth analyses of BMI and GDM in specific racial/ethnic groups. In addition, our analysis did not account for potential confounders such as physical activity, diet, and genetics because PRAMS does not collect information on these indicators.

Finally, the quality of the GDM variable on the revised 2003 birth certificate has not been validated in the published literature. However, studies in states that have amended their 1989 birth certificate to differentiate between preexisting diabetes and GDM have consistently shown specificities above 98% and sensitivities ranging from 46% to 83% in identifying GDM.34 With the implementation of the revised 2003 birth certificate and as certifiers have become more familiar with the separate categories, accuracy of GDM identification most likely has improved.35

Conclusions

A large percentage of GDM cases are potentially attributable to overweight and obesity and could be avoided by preventing these conditions. Data such as ours can help public health officials estimate the potential effects of prevention interventions on GDM prevalence rates. Lifestyle interventions designed to reduce BMIs have the potential to lower GDM risk. Therefore, public health efforts to promote recommended levels of physical activity and healthy eating habits among women of reproductive age should be intensified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Morrow for his technical expertise and consultation. Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) included in this study were collected at the state level by the following state working group collaborators and their staff: Albert Woolbright (Alabama), Kathy Perham-Hester (Alaska), Mary McGehee (Arkansas), Alyson Shupe (Colorado), Charlon Kroelinger (Delaware), Jamie Fairclough (Florida), Carol Hoban (Georgia), Mark Eshima (Hawaii), Theresa Sandidge (Illinois), Joan Wightkin (Louisiana), Kim Haggan (Maine), Diana Cheng (Maryland), Hafsatou Diop (Massachusetts), Violanda Grigorescu (Michigan), Jan Jernell (Minnesota), Marilyn Jones (Mississippi), Venkata Garikapaty (Missouri), JoAnn Dotson (Montana), Brenda Coufal (Nebraska), Lakota Kruse (New Jersey), Eirian Coronado (New Mexico), Anne Radigan-Garcia (New York State), Candace Mulready-Ward (New York City), Paul Buescher (North Carolina), Sandra Anseth (North Dakota), Connie Geidenberger (Ohio), Alicia Lincoln (Oklahoma), Kenneth Rosenberg (Oregon), Kenneth Huling (Pennsylvania), Sam Viner-Brown (Rhode Island), Mike Smith (South Carolina), Christine Rinki (South Dakota), Kate Sullivan (Texas), David Law (Tennessee), Laurie Baksh (Utah), Peggy Brozicevic (Vermont), Marilyn Wenner (Virginia), Linda Lohdefinck (Washington), Melissa Baker (West Virginia), Katherine Kvale (Wisconsin), and Angi Crotsenberg (Wyoming). Data were also collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention PRAMS team.

Human Participant Protection

The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System protocol was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's institutional review board; the analysis plan was approved in the participating states. Informed consent was obtained from all participants via either mail or telephone.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists: gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98(3):525–538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt KJ, Schuller KL. The increasing prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2007;34(2):173–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casey BM, Lucas MJ, Mcintire DD, Leveno KJ. Pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes compared with the general obstetric population. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90(6):869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong X, Saunders LD, Wang FL, Demianczuk NN. Gestational diabetes mellitus: prevalence, risk factors, maternal and infant outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001;75(3):221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barahona MJ, Sucunza N, Garcia-Patterson A, et al. Period of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis and maternal and fetal morbidity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84(7):622–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen DM, Sorensen B, Feilberg-Jorgensen N, Westergaard JG, Beck-Nielsen H. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in 143 Danish women with gestational diabetes mellitus and 143 controls with a similar risk profile. Diabet Med 2000;17(4):281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Quick WW, Yang W, et al. Cost of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States in 2007. Popul Health Manag 2009;12(3):165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bottalico JN. Recurrent gestational diabetes: risk factors, diagnosis, management, and implications. Semin Perinatol 2007;31(3):176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002;25(10):1862–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.England LJ, Dietz PM, Njoroge T, et al. Preventing type 2 diabetes: public health implications for women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200(4):e1–e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Chen W, Sacks DA. Trends in the prevalence of preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus among a racially/ethnically diverse population of pregnant women, 1999–2005. Diabetes Care 2008;31(5):899–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara A, Kahn HS, Quesenberry CP, Riley C, Hedderson MM. An increase in the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus: northern California, 1991–2000. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103(3):526–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Dietz PM, England L, Morrow B, Callaghan WM. Trends in pre-pregnancy obesity in 9 states, 1993–2003. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(4):986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabelea D, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hartsfield CL, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF, McDuffie RS. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) over time and by birth cohort: Kaiser Permanente of Colorado GDM Screening Program. Diabetes Care 2005;28(3):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Kim SY, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007;30(8):2070–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanders WD, Rhodes PH. Large sample confidence intervals for regression standardized risks, risk ratios, and risk differences. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(7):697–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graubard BI, Fears TR. Standard errors for attributable risk for simple and complex sample designs. Biometrics 2005;61(3):847–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine BJ. The other causality question: estimating attributable fractions for obesity as a cause of mortality. Int J Obes 2008;32(suppl 3):S4–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized Additive Models London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 20.S-Plus Version 7, Guide to Statistics Seattle, WA: Insightful Corp; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torloni MR, Betran AP, Horta BL, et al. Prepregnancy BMI and the risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2009;10(2):194–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana JS, Li TY, Manson JE, Hu FB. Adiposity compared with physical inactivity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2007;30(1):53–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146(3):214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, et al. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2006;29(7):1585–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, et al. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: the Diabetes Prevention Program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;142(8):611–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratner RE. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in women with previous gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30(suppl 2):S242–S245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang C, Solomon CG, Manson JE, Hu FB. A prospective study of pregravid physical activity and sedentary behaviors in relation to the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(5):543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C, Liu S, Solomon CG, Hu FB. Dietary fiber intake, dietary glycemic load, and the risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2006;29(10):2223–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artal R, Catanzaro RB, Gavard JA, Mostello DJ, Friganza JC. A lifestyle intervention of weight-gain restriction: diet and exercise in obese women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2007;32(3):596–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 2002;288(14):1723–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2007;56(6):1–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chu SY, Kim SY, Bish CL. Prepregnancy obesity prevalence in the United States, 2004–2005. Matern Child Health J 2009;13(5):614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devlin HM, Desai J, Walaszek A. Reviewing performance of birth certificate and hospital discharge data to identify births complicated by maternal diabetes. Matern Child Health J 2009;13(5):660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menacker F, Martin JA. Expanded health data from the new birth certificate, 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2008;56(13):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]