Abstract

Objectives. We compared the ability of several heat–health warning systems to predict days of heat-associated mortality using common data sets.

Methods. Heat–health warning systems initiate emergency public health interventions once forecasts have identified weather conditions to breach predetermined trigger levels. We examined 4 commonly used trigger-setting approaches: (1) synoptic classification, (2) epidemiologic assessment of the temperature–mortality relationship, (3) temperature–humidity index, and (4) physiologic classification. We applied each approach in Chicago, Illinois; London, United Kingdom; Madrid, Spain; and Montreal, Canada, to identify days expected to be associated with the highest heat-related mortality.

Results. We found little agreement across the approaches in which days were identified as most dangerous. In general, days identified by temperature–mortality assessment were associated with the highest excess mortality.

Conclusions. Triggering of alert days and ultimately the initiation of emergency responses by a heat–health warning system varies significantly across approaches adopted to establish triggers.

Prompted by growing concerns about global warming and past dramatic heat wave events,1–3 many jurisdictions worldwide have introduced partnerships between weather services, civil protection agencies, and public health authorities to inform their residents about and protect them from the dangers of hot weather to health.4–9 Major components of these heat plans are announcing advisories and implementing emergency measures when forecast weather is expected to adversely affect the health of all or selected residents of a city or region. Collectively, such initiatives are called heat–health warning systems (HHWSs).

HHWSs are designed to be activated, or triggered, once temperature and possibly other weather factors are forecast to breach predefined values expected to be associated with unacceptable levels of adverse health effects. These values are commonly referred to as triggers, and the optimal setting of triggers facilitates efficient and coordinated emergency responses; effective communication among civil protection, meteorological, and public health authorities; and, of course, reduction of heat-related mortality and morbidity.

Fundamentally different trigger-setting procedures are used by various HHWSs in cities, regions, and countries across North America and Europe, and in some parts of Australia and Asia.10–13 Such variations reflect different theories about the nature of the relationship between heat and health. For example, triggers may be determined by epidemiological analysis of retrospective mortality data12 or from experimental models of heat stress and known physiologic effects of heat fluxes.14 Variations between the approaches may also reflect differences in specific objectives and proprietorship. More prosaic reasons may also account for differences: after the 2003 heat wave in Paris, France, French researchers were given limited time and resources to devise a system and from necessity employed a relatively simple approach.12

Despite these differences, the general goal of each system should, in principle, be the same: to identify those days associated with the largest health effects attributable to adverse weather conditions. To date, however, no study has examined the extent to which identification (and eventual triggering) of heat-alert days depends on the particular approach used to establish triggers. We compared alternative approaches for setting HHWS triggers by measuring how well they predicted heat-associated mortality from a common set of historical weather and mortality records. Our primary objective was to assess the degree to which the same heat-alert days were identified by the different approaches.

METHODS

We obtained daily counts of all-cause mortality and hourly weather data for 20-year periods for the metropolitan areas of Chicago, Illinois (1985–2004); London, United Kingdom (1984–2003); and Montreal, Canada (1983–2002); and for the city of Madrid, Spain (1987–2006). We selected these locations because data were available and because they represented different climatic conditions. Wherever possible, we requested data from before the advent of a functioning HHWS, which may have served to alter the relationship between weather and health. We obtained mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics (Chicago), Office for National Statistics (London), Madrid Regional Health Department (Madrid), and Quebec Institute of Public Health Info-Centre (Montreal).

We obtained hourly weather data for the following meteorological variables: temperature, dew point, barometric pressure, wind direction, wind speed, and cloud cover. We estimated hourly solar radiation from hourly cloud cover data, hourly extraterrestrial solar radiation for clear sky, zenith angle (the angle from a vertical line to the position of the sun), and other meteorological factors. Where appropriate, we created daily measures of maximum and minimum temperature from the hourly temperature values. All weather data came from the National Climate Data Center (Chicago), British Atmospheric Data Centre (London), Spanish National Institute of Meteorology (Madrid), and Environment Canada (Montreal).

Approaches to Determining Triggers

We grouped the various trigger-setting approaches currently in operation in HHWSs across the world into 4 main types: synoptic classification, epidemiologic assessment of the temperature–mortality relationship, temperature–humidity index, and physiologic classification. Detailed information about each approach and examples of locations where they are currently used is presented in Appendix 1 (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) and has been published elsewhere.7,12,15,16

In brief, synoptic classification takes into account that health may be affected by several weather factors acting in combination. It identifies different air-mass categories and uses epidemiological analysis of historical mortality data to model the mortality relationship within each category. This system is in most widespread use. The temperature–mortality approach also uses epidemiological analysis of historical mortality data but simply models the direct relationship between temperature and mortality. Triggers are based on temperature values that have an acceptable combination of sensitivity and specificity in identifying days of high mortality.

The temperature–humidity index encompasses the spectrum of existing indexes that are composite measures of temperature and humidity. Apparent temperature is an example of such an index.17 Humidex is more commonly used operationally, so we used it to represent the third approach.15 The physiologic approach relies on principles of heat-budget models of the human body. We used the environmental stress index (ESI), which is derived from commonly used and easily measured weather variables and was developed and tested for hot–humid and hot–dry climates.18 It has been found to be highly correlated with the wet-bulb and globe temperature, a physiologic heat metric widely used in occupational health settings.19 The synoptic and temperature–mortality approaches rely on explicit assessment of location-specific mortality; the Humidex and ESI approaches have implicit notions of the relationship between heat and health.

Analysis

We applied each of these 4 approaches to each of the 4 cities to identify heat-adverse days (i.e., those days expected to be associated with the highest mortality attributable to heat). In a series of 3 steps, we assessed the degree to which the different systems identified the same days and the level of excess mortality that occurred on identified days.

Step 1.

The investigator for each approach received 20 years of mortality and weather data from each of the 4 cities, of which 10 years served to calibrate the approaches. To achieve a good spread of hot and cool summers in both the 10-year calibration data set and the remaining 10 years, we assigned the hottest summer (according to the average daily mean temperature during June through August) to the calibration data set, along with odd-numbered years as ranked by heat (third hottest, fifth hottest, etc.). The remaining data set consisted of the even-numbered years by heat ranking (second hottest, fourth hottest, etc.). The data sets therefore did not comprise contiguous years. The allocation of the hottest summer to the calibration data set ensured that the extremely hot summers of Chicago 1995 and Europe 2003 both contributed to the calibration of the approaches, all of which used the same sets of years as calibration data.

The algorithm for each approach was applied to the 10-year calibration data sets to identify the weather conditions estimated to be associated with the largest adverse health effects in each of the 4 cities. The investigators for the first 2 approaches fully documented the algorithm applied and ensured that it was as true as possible to the method originally developed for use in the respective HHWSs. This step was not necessary for the Humidex and ESI approaches because neither required explicit characterization of the weather–mortality relationship in each location.

Step 2.

The investigator for each method applied the weather parameters specified in step 1 to the remaining 10-year data set and identified and ranked the 50 days expected to be the most heat adverse for each city. No death data were provided for these 10 years, so ranking was not influenced by actual mortality levels.

Step 3.

We assembled the ranked heat-adverse days identified by each system centrally for comparison by the following procedure: (1) we described the extent of overlap between days identified by the various systems, (2) we observed mean temperature and total deaths on identified days (observed death counts were available centrally), and (3) we estimated total excess mortality and percentage excess mortality on identified days.

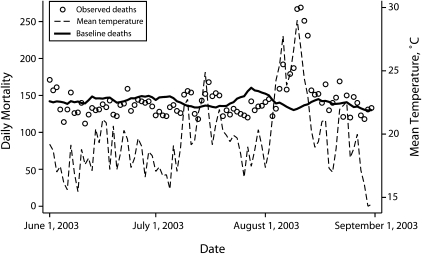

Excess mortality was calculated as the difference (in absolute and percentage terms) between observed deaths and a baseline level. The baseline was derived from mortality counts averaged across the 2 previous and 2 subsequent years of each triggered day. To obtain a stable baseline, in our averaging we considered days matched by day of year to the triggered day and 3 days before and after the triggered day. Thus, for a given triggered day, we calculated the baseline by averaging 28 days (4 years × 7 days). In situations in which the triggered day occurred at the margins of the data set, mortality data sets extending beyond the 20-year periods were made available so that the baseline could still be created from a contribution of 28 days. To illustrate the suitability of the baseline derivation, we show in Figure 1 the observed and baseline mortality levels in London for the hot summer of 2003.

FIGURE 1.

Daily mortality and mean temperature: London, United Kingdom, June 1, 2003–August 31, 2003.

Decisions on the method of calculation of excess deaths, in particular the derivation of a baseline, were a priori and completely independent of any calculation of excess deaths conducted as part of the algorithms of the individual systems. All calculations were conducted in Stata version 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents summary statistics of the 4 study areas, separated by calibration years and test years. Chicago and Madrid had considerably hotter summers than did the other 2 locations. Madrid's data are for the city rather than metropolitan area and therefore record by far the lowest death count.

TABLE 1.

Average Daily Temperatures and Mortality Counts During June Through August: Chicago, IL, 1985–2004; London, United Kingdom, 1984–2003; Madrid, Spain, 1987–2006; and Montreal, Canada, 1983–2002

| Calibration Yearsa |

Test Yearsb |

|||||||

| Minimum Temperature, °C | Mean Temperature, °C | Maximum Temperature, °C | Mortality, No. | Minimum Temperature, °C | Mean Temperature, °C | Maximum Temperature, °C | Mortality, No. | |

| Chicago, IL | 16.52 | 22.13 | 27.75 | 161.6 | 16.10 | 21.89 | 27.68 | 161.2 |

| London, United Kingdom | 13.16 | 17.84 | 22.51 | 153.1 | 12.81 | 17.65 | 22.48 | 161.1 |

| Madrid, Spain | 18.27 | 24.68 | 31.10 | 66.6 | 17.81 | 24.35 | 30.89 | 65.8 |

| Montreal, Canada | 15.42 | 20.07 | 24.72 | 131.9 | 15.07 | 19.94 | 24.81 | 129.4 |

Years used to calibrate the 4 systems for determining heat-adverse days were the years from the data set that were the hottest, the third hottest, the fifth hottest, and so on. Calibration years for Chicago were 1985–1987, 1993, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, and 2003; for London, 1986, 1988, 1992, 1994, 1996–1998, 2000, 2001, and 2003; for Madrid, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, and 2005; and for Montreal, 1989–1992, 1994–1996, and 1998–2000.

Test years, used to compare the 4 methods for determining heat-adverse days, were for Chicago, 1988–1992, 1994, 1996, 1999, 2001, and 2004; for London, 1984, 1985, 1987, 1989–1991, 1993, 1995, 2002; for Madrid, 1988, 1990, 1992–1994, 1996, 1998, 2002, 2004, and 2006; and for Montreal, 1983–1988, 1993, 1997, 2001, and 2002.

Table 2 lists the dates of the 20 most heat-adverse days identified by each system, ranging from the most heat adverse (rank 1) to the 20th most heat adverse (rank 20) and shows degree of agreement between methods. The very hot summers of Chicago 1995 and Europe 2003 were allocated to their respective calibration data sets and so do not appear as part of the results here. Agreement was poor for Chicago and Madrid, with no date appearing in the top 20 ranking of every approach. For Chicago, the highest-ranked date identified by the synoptic approach was not identified at all in the top 20 days of the other 3 methods. Similarly, in Madrid, the top-ranked date identified by the temperature–mortality approach was not present in the top 20 days of any of the other 3 approaches. Agreement was better for London and Montreal, with 6 dates common to the top 20 rankings of all approaches in both cities.

TABLE 2.

Dates of the 20 Most Heat-Adverse Days Identified by 4 Approaches to Determining Triggers for Heat Warnings: Chicago, IL, 1985–2004; London, United Kingdom, 1984–2003; Madrid, Spain, 1987-2006; and Montreal, Canada, 1983–2002

| Dates Identified by Synoptic Classificationb |

Dates Identified by Temperature–Mortality Approachc |

Dates Identified by Humidexd |

Dates Identified by Environmental Stress Indexe |

|||||||||||||

| Ranka | Chicago | London | Madrid | Montreal | Chicago | London | Madrid | Montreal | Chicago | London | Madrid | Montreal | Chicago | London | Madrid | Montreal |

| 1 | 8/08/88 | 8/03/90 | 7/29/94 | 8/08/01 | 8/03/88 | 8/03/95 | 8/26/92 | 7/03/02f | 7/05/94 | 8/03/90 | 7/08/96 | 7/02/02f | 7/05/94 | 8/01/95f | 7/18/96 | 7/02/02f |

| 2 | 8/17/88 | 8/04/90f | 7/28/94 | 8/09/01f | 8/04/88 | 8/02/95f | 8/07/92 | 8/09/01f | 7/30/99 | 7/10/95 | 7/26/92 | 7/03/02f | 6/15/94 | 7/10/95 | 6/03/88 | 7/03/02f |

| 3 | 5/01/96 | 8/15/02 | 7/27/94 | 8/07/01 | 8/02/88 | 7/23/89 | 7/21/90 | 8/14/02 | 7/29/99 | 8/01/95f | 7/28/93 | 8/03/88 | 6/14/94 | 7/29/02 | 7/29/93 | 7/13/87 |

| 4 | 6/20/88 | 7/22/89f | 7/28/92 | 6/15/01 | 8/17/88 | 7/24/89 | 7/25/04 | 8/08/01 | 7/22/99 | 8/02/90f | 7/01/96 | 7/12/87f | 6/18/94 | 8/04/90f | 8/24/04 | 7/06/93 |

| 5 | 8/02/04 | 8/02/90f | 7/20/98 | 7/03/02f | 6/21/88 | 8/04/95 | 7/12/06 | 8/05/88 | 7/04/90 | 8/04/90f | 7/18/96 | 8/04/88f | 7/29/99 | 7/31/95f | 7/28/93 | 7/11/87f |

| 6 | 7/08/88 | 8/01/95f | 7/15/94 | 7/09/88 | 7/01/99 | 8/04/90f | 7/20/90 | 8/04/88f | 8/16/88 | 7/22/89f | 7/29/93 | 7/13/87 | 7/30/99 | 8/02/95f | 7/27/92 | 7/09/87 |

| 7 | 7/09/88 | 7/30/84 | 7/20/06 | 6/15/88 | 6/22/88 | 8/03/90 | 7/11/06 | 7/04/02 | 7/10/89 | 7/31/95f | 8/20/93 | 7/06/93 | 7/22/99 | 7/06/89 | 7/10/06 | 8/09/01f |

| 8 | 8/06/88 | 7/30/02 | 7/18/98 | 7/02/02f | 7/16/88 | 8/01/95f | 8/21/93 | 7/13/87 | 8/09/92 | 7/29/02 | 8/05/93 | 8/09/01f | 8/07/96 | 7/22/89f | 7/17/06 | 8/04/88f |

| 9 | 8/15/88 | 7/31/95f | 8/03/06 | 8/04/88f | 7/22/91 | 7/22/89f | 8/20/93 | 8/15/02 | 8/27/90 | 7/06/89 | 7/22/96 | 7/01/02 | 7/20/94 | 7/21/90 | 8/20/93 | 7/04/83 |

| 10 | 6/18/94 | 8/10/91 | 7/26/94 | 7/06/93 | 7/27/99 | 8/02/99 | 7/13/06 | 7/24/01 | 8/17/88 | 8/02/95f | 7/27/92 | 8/16/87 | 6/17/94 | 7/30/95 | 7/10/94 | 6/15/01 |

| 11 | 6/20/94 | 7/11/91 | 7/30/94 | 7/12/87f | 7/26/99 | 8/05/90 | 7/22/90 | 8/16/02 | 7/05/99 | 7/21/90 | 7/15/92 | 7/11/87f | 7/04/94 | 6/29/87 | 7/01/96 | 8/17/87 |

| 12 | 7/15/88 | 7/09/91 | 8/12/98 | 8/12/02 | 8/18/88 | 7/31/95f | 8/06/92 | 7/12/87f | 8/07/01 | 7/20/95 | 7/18/92 | 8/05/88 | 7/04/90 | 7/20/95 | 7/20/90 | 7/08/88 |

| 13 | 8/04/88 | 8/02/95f | 6/16/96 | 7/22/02 | 7/20/91 | 8/02/90f | 7/14/06 | 7/10/88 | 7/21/99 | 6/30/95 | 8/24/04 | 7/04/83 | 8/16/88 | 6/28/95 | 5/14/98 | 8/07/01 |

| 14 | 7/07/88 | 7/10/95 | 7/21/06 | 8/03/88 | 8/05/01 | 7/21/90 | 7/26/04 | 8/06/88 | 7/23/99 | 6/29/87 | 7/20/90 | 7/08/88 | 7/05/99 | 7/21/95 | 7/09/06 | 7/12/87f |

| 15 | 5/16/91 | 7/29/02 | 7/12/06 | 7/11/87f | 7/21/91 | 8/01/99 | 7/29/02 | 8/10/01 | 7/04/99 | 7/23/89 | 7/21/96 | 8/13/88 | 7/24/99 | 7/05/91 | 7/21/90 | 8/03/88 |

| 16 | 7/10/88 | 8/21/91 | 7/25/96 | 7/01/02 | 8/16/88 | 8/12/95 | 8/12/98 | 7/09/88 | 7/28/99 | 8/21/87 | 8/27/94 | 8/17/87 | 6/16/94 | 8/11/95 | 7/30/98 | 7/30/88 |

| 17 | 7/25/99 | 7/28/95 | 7/17/06 | 7/04/83 | 6/16/94 | 6/30/95 | 8/03/06 | 7/11/87f | 9/06/90 | 7/15/90 | 5/14/98 | 8/14/02 | 7/21/99 | 8/02/90f | 7/17/92 | 8/08/01 |

| 18 | 7/22/91 | 6/30/95 | 8/07/92 | 8/17/87 | 7/02/99 | 7/25/89 | 7/15/06 | 8/13/02 | 6/15/94 | 8/01/90 | 9/03/94 | 8/07/01 | 8/05/96 | 7/29/95 | 7/20/96 | 7/09/88 |

| 19 | 7/13/99 | 7/23/89 | 8/02/06 | 8/13/88 | 8/14/88 | 8/20/95 | 7/29/94 | 7/02/02f | 7/24/99 | 7/30/95 | 7/03/96 | 7/24/01 | 7/23/99 | 8/03/95 | 8/05/93 | 7/10/88 |

| 20 | 7/21/91 | 8/31/84 | 8/01/04 | 8/02/88 | 8/15/88 | 8/03/99 | 8/07/93 | 7/14/87 | 8/18/90 | 7/24/89 | 6/29/94 | 7/09/87 | 7/06/94 | 6/17/02 | 7/01/94 | 7/23/01 |

Note. Heat-adverse days are identified as likely to negatively affect health.

From most heat adverse (1) to 20th-most heat adverse (20).

This approach identifies air mass types based on a combination of weather factors.

This approach models the direct relationship of temperature and mortality.

This approach is based on a temperature-humidity index.

This approach relies on physiologic principles of heat-budget models of the human body.

Dates identified by all 4 systems as among the top 20 heat-adverse days.

Table 3 lists the averaged daily mean temperature, daily number of deaths, daily excess deaths, and percentage daily excess deaths for a selection of the ranked days. In Chicago, the most heat-adverse day identified by the synoptic method was associated with a greater percentage excess than was the top day identified by the temperature–mortality approach, despite the lower mean temperature. At lower-ranked days, the percentage excesses on days identified by the temperature–mortality approach were broadly similar to the days identified by the synoptic method, despite consistently identifying hotter days. In general, the Humidex and ESI approaches tended to identify days of lower-percentage excess mortality in Chicago.

TABLE 3.

Averaged Daily Mean Temperature, Observed Deaths, Excess Deaths and Percentage Excess Deaths on Days Identified as Heat Adverse by 4 Approaches to Determining Triggers for Heat Warnings: Chicago, IL, 1985–2004; London, United Kingdom, 1984–2003; Madrid, Spain, 1987-2006; and Montreal, Canada, 1983–2002

| Synoptic Classificationb |

Temperature–Mortality Approachc |

Humidexd |

Environmental Stress Indexe |

|||||||||||||

| Top-Ranked Heat-Adverse Daysa | Average Mean Temperature, °C | Average No. of Daily Deaths | Average No. of Daily Excess Deaths | Average Excess, % | Average Mean Temperature, °C | Average No. of Daily Deaths | Average No. of Daily Excess Deaths | Average Excess, % | Average Mean Temperature, °C | Average No. of Daily Deaths | Average No. of Daily Excess Deaths | Average Excess, % | Average Mean Temperature, °C | Average No. of Daily Deaths | Average No. of Daily Excess Deaths | Average Excess, % |

| Chicago | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 29.2 | 201.0 | 38.7 | 23.9f | 31.1 | 174.0 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 28.3 | 188.0 | 24.0 | 14.6 | 28.3 | 188.0 | 24.0 | 14.6 |

| 3 | 23.9 | 191.3 | 30.2 | 18.7f | 31.3 | 190.3 | 29.1 | 18.0 | 23.8 | 186.7 | 26.0 | 16.2 | 29.3 | 174.0 | 7.4 | 4.5 |

| 5 | 24.3 | 178.8 | 18.6 | 11.6 | 31.0 | 185.8 | 24.6 | 15.3f | 25.6 | 170.0 | 8.9 | 5.5 | 26.6 | 175.8 | 10.9 | 6.6 |

| 10 | 25.5 | 178.5 | 17.3 | 10.7 | 30.1 | 180.4 | 20.5 | 12.8f | 27.4 | 171.1 | 10.8 | 6.8 | 25.6 | 172.5 | 9.4 | 5.8 |

| 15 | 26.0 | 176.5 | 15.0 | 9.2 | 29.7 | 177.2 | 18.1 | 11.4f | 26.5 | 168.1 | 8.3 | 5.2 | 26.5 | 170.7 | 8.3 | 5.1 |

| 20 | 26.3 | 171.7 | 10.9 | 6.7 | 29.3 | 173.9 | 14.8 | 9.3f | 26.7 | 166.4 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 26.7 | 169.1 | 7.4 | 4.6 |

| 30 | 25.6 | 173.1 | 12.5 | 7.7 | 29.1 | 172.7 | 13.0 | 8.1f | 26.6 | 169.2 | 8.4 | 5.2 | 26.6 | 170.4 | 8.7 | 5.5 |

| 40 | 26.0 | 175.1 | 14.4 | 8.9f | 28.7 | 170.6 | 10.7 | 6.7 | 26.9 | 168.6 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 26.6 | 170.4 | 8.3 | 5.2 |

| 50 | 25.4 | 174.0 | 12.9 | 8.0f | 28.5 | 168.5 | 8.2 | 5.1 | 26.9 | 167.2 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 26.4 | 169.6 | 7.3 | 4.6 |

| London | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 27.4 | 221.0 | 61.8 | 38.8 | 26.1 | 214.0 | 65.3 | 43.9f | 27.4 | 221.0 | 61.8 | 38.8 | 26.6 | 178.0 | 27.1 | 18.0 |

| 3 | 25.6 | 191.3 | 35.3 | 22.1 | 26.3 | 200.7 | 45.1 | 29.4f | 26.0 | 190.0 | 35.9 | 23.0 | 25.3 | 171.7 | 21.5 | 14.3 |

| 5 | 26.0 | 192.2 | 33.2 | 20.6 | 25.0 | 198.4 | 41.9 | 26.9f | 26.2 | 193.4 | 37.2 | 23.6 | 25.6 | 185.0 | 32.8 | 21.5 |

| 10 | 25.0 | 188.3 | 31.1 | 19.9 | 25.8 | 197.4 | 41.3 | 26.5f | 26.0 | 193.7 | 37.0 | 23.5 | 25.5 | 188.0 | 31.8 | 20.3 |

| 15 | 24.5 | 182.6 | 26.5 | 17.0 | 25.3 | 192.7 | 36.8 | 23.6f | 25.3 | 190.3 | 31.7 | 19.9 | 24.6 | 184.0 | 27.1 | 17.2 |

| 20 | 24.0 | 179.4 | 22.2 | 14.3 | 24.7 | 188.3 | 32.4 | 20.8f | 24.9 | 187.1 | 28.2 | 17.7 | 24.5 | 182.1 | 26.5 | 17.0 |

| 30 | 23.0 | 175.1 | 16.6 | 10.7 | 24.1 | 181.3 | 25.1 | 16.1f | 24.2 | 180.7 | 23.2 | 14.6 | 24.0 | 177.8 | 21.7 | 13.9 |

| 40 | 23.1 | 173.2 | 15.9 | 10.3 | 23.8 | 175.1 | 19.7 | 12.7 | 24.0 | 177.3 | 19.1 | 12.0 | 23.9 | 179.4 | 21.5 | 13.6f |

| 50 | 22.7 | 172.4 | 14.4 | 9.3 | 23.5 | 173.2 | 17.1 | 11.0 | 23.8 | 178.2 | 19.3 | 12.2f | 23.7 | 177.2 | 18.0 | 11.4 |

| Madrid | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 29.2 | 70.0 | –1.5 | –2.1f | 29.5 | 55.0 | –5.8 | –9.5 | 17.3 | 56.0 | –10.1 | –15.2 | 27.8 | 61.0 | –7.6 | –11.0 |

| 3 | 29.4 | 71.1 | –2.1 | –2.7 | 29.7 | 69.3 | 3.3 | 4.2f | 25.3 | 64.3 | –4.6 | –7.0 | 27.5 | 66.7 | –1.3 | –2.2 |

| 5 | 29.5 | 75.2 | 4.4 | 7.0f | 30.1 | 68.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 26.3 | 65.2 | –2.9 | –4.3 | 28.1 | 72.4 | 4.5 | 6.8 |

| 10 | 29.6 | 70.8 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 30.2 | 70.4 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 28.3 | 66.7 | –1.8 | –2.6 | 29.0 | 73.5 | 6.8 | 10.8f |

| 15 | 29.3 | 70.8 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 29.8 | 72.1 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 28.6 | 69.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 28.2 | 73.1 | 5.7 | 8.9f |

| 20 | 29.3 | 71.9 | 3.7 | 5.8 | 29.7 | 71.6 | 4.1 | 6.0 | 27.2 | 67.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 28.4 | 73.5 | 5.8 | 9.1f |

| 30 | 29.2 | 72.3 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 29.8 | 74.2 | 6.8 | 10.2f | 27.7 | 68.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 28.4 | 72.8 | 5.7 | 9.0 |

| 40 | 28.8 | 72.1 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 29.6 | 74.8 | 7.0 | 10.4f | 27.7 | 68.1 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 28.5 | 72.4 | 5.3 | 8.2 |

| 50 | 28.6 | 71.3 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 29.5 | 74.8 | 7.0 | 10.5f | 27.8 | 69.5 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 28.6 | 71.5 | 4.1 | 6.5 |

| Montreal | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 27.1 | 155.0 | 23.2 | 17.6 | 28.9 | 222.0 | 85.3 | 62.4f | 29.0 | 183.0 | 45.1 | 32.7 | 29.0 | 183.0 | 45.1 | 32.7 |

| 3 | 28.2 | 154.7 | 21.5 | 16.1 | 28.6 | 183.3 | 46.6 | 34.0 | 28.0 | 177.0 | 43.5 | 31.7 | 28.6 | 212.3 | 80.5 | 62.3f |

| 5 | 28.2 | 173.6 | 37.8 | 27.7 | 28.0 | 168.6 | 35.0 | 25.8 | 28.1 | 168.4 | 38.3 | 28.8 | 27.9 | 183.8 | 52.9 | 41.1f |

| 10 | 28.0 | 167.5 | 34.3 | 25.7 | 27.8 | 174.0 | 40.9 | 31.1f | 27.6 | 163.2 | 33.6 | 26.0 | 27.7 | 169.9 | 39.0 | 30.0 |

| 15 | 27.7 | 163.5 | 30.6 | 23.0 | 27.3 | 172.5 | 39.9 | 30.4f | 27.4 | 156.9 | 28.7 | 22.3 | 27.7 | 160.8 | 31.2 | 24.0 |

| 20 | 27.5 | 157.4 | 26.3 | 19.8 | 27.2 | 174.2 | 41.8 | 32.1f | 27.5 | 155.3 | 25.9 | 19.9 | 27.6 | 162.4 | 32.0 | 24.6 |

| 30 | 27.0 | 153.4 | 22.9 | 17.4 | 26.5 | 166.5 | 32.7 | 25.0f | 27.4 | 155.6 | 26.3 | 20.3 | 27.3 | 158.9 | 28.6 | 21.9 |

| 40 | 26.5 | 150.9 | 19.5 | 14.8 | 26.2 | 160.7 | 27.7 | 21.1f | 27.1 | 155.8 | 26.3 | 20.2 | 27.1 | 157.6 | 27.1 | 20.7 |

| 50 | 26.5 | 152.5 | 22.0 | 16.9 | 26.1 | 158.1 | 25.7 | 19.6f | 26.6 | 152.7 | 23.8 | 18.4 | 26.7 | 155.9 | 25.1 | 19.3 |

Note. Heat-adverse days are identified as likely to negatively affect health.

Ranked in order of heat-adverse conditions, from 1 (most adverse) to 50.

This approach identifies air mass types based on a combination of weather factors.

This approach models the direct relationship of temperature and mortality.

This approach is based on a temperature-humidity index.

This approach relies on physiologic principles of heat-budget models of the human body.

System identifying the day or days with the greatest percentage excess at each selection of rankings.

The top day identified in London by the temperature–mortality approach was associated with the lowest mean temperature but the greatest percentage excess mortality compared with the top day of each of the other 3 approaches. For the remaining ranked days, although temperatures were similar on days identified across the approaches, the temperature–mortality approach consistently identified days of greater percentage excess mortality compared with the Humidex, which in turn consistently identified days of greater percentage excess mortality compared with the other 2 approaches. We observed a similar pattern in Montreal, with the temperature–mortality approach performing the best, followed in order by the ESI, Humidex, and synoptic approaches.

In Madrid, no approach identified a top-ranked day that was associated with an excess in mortality. For the other ranked days, the temperature–mortality and ESI approaches identified days of higher excess mortality, followed by the synoptic approach and then Humidex.

DISCUSSION

It is important to note that our study was not an evaluation of the various HHWSs in operation around the world. Formal evaluations of such systems require consideration of several aspects we did not address. For example, the effectiveness of an HHWS is highly dependent on the accuracy of forecast weather; temperature is more accurately forecast than is humidity, so this may favor an approach relying on temperature forecasts alone rather than on a temperature–humidity index. The choice of trigger-setting approach will likely also depend on other considerations, such as economic costs of development and implementation. To date, few evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of HHWSs have been carried out.4,20–22

We also did not undertake to identify a gold-standard approach for trigger setting in HHWSs. Any attempt to rank the 4 methods would require consideration of the excess deaths occurring on identified days. By that criterion, the temperature–mortality approach generally identified days of greatest excess mortality most accurately. However, this may simply reflect the fact that our approach to calculating excess mortality, although logical and established independently of the system algorithms, most closely resembled the temperature-mortality system's own approach to calculating excess mortality. Still, by the criterion of simple identification of days expected to be associated with large adverse mortality effects, we found little agreement across the 4 approaches.

In general, the agreement we observed was greater in the cooler cities of London and Montreal. By contrast, in Chicago, excess mortality on days identified by the synoptic approach were similar to those identified by the temperature–mortality approach, despite consistently lower temperatures on the days identified by the synoptic approach. This suggests that the additional weather factors that contribute to the synoptic method (namely, dew point, barometric pressure, wind direction, wind speed, and cloud cover) may be important predictors of mortality in a hot city such as Chicago but less so in cooler cities. In Madrid agreement was also poor, and none of the methods identified days of any notable mortality excesses within their 3 highest-ranked days. This curious result may indicate that the population of Madrid is well adapted to protecting itself during extreme-heat days. None of the city's highest-ranked days occurred after 2003, when the introduction of public health intervention measures may have served to reduce risk.

We found closer agreement between the synoptic and temperature–mortality approaches and between the ESI and Humidex. The former 2 methods are based on explicit mortality assessments of setting-specific data; the latter 2 were originally designed to indicate conditions of heat stress or discomfort (not necessarily heat-related death) and are not calibrated with local health data. Also, both the synoptic and temperature–mortality approaches consider cumulative day effects of heat exposure, unlike the other 2 methods. For our evaluation of the ESI, data on solar radiation contained many missing values and hourly data were not always available, so it is somewhat surprising that this approach was still able to identify heat-adverse days with relative success. For Chicago, information on solar radiation was only available from a neighboring station approximately 40 miles away, which may have contributed to this approach's poorer performance in this location.

It should be noted that each approach was constrained to identify the same number of days. So the only difference between the approaches lay in which days were identified. This constraint was somewhat unnatural for some of the methods and not fully representative of how they operate in practice. However, without this constraint, comparison between the approaches would not have been very meaningful.

In operation, the number of alert days triggered in any system will depend on the priorities of the coordinating bodies in a particular situation. Calling an alert only during days of extreme weather conditions runs the risk of ignoring other days when substantial public health effects may also be present, whereas calling an alert more often results in more false-positive days, which may desensitize the public to the dangers of hot weather, as well as expend more public resources. During the approximately 5 years that the 2 Canadian HHWSs have been operating in their current form, Toronto, which uses the synoptic approach, has issued numerous alerts, whereas the temperature–mortality approach used by the city of Montreal has never triggered an alert.23 In our findings, we placed more emphasis on agreement between the highest-ranked heat-adverse days and less on the lower-ranked days, for which it may be unrealistic to expect good agreement across the approaches.

The 4 approaches we assessed are representative of essentially all threshold-setting procedures currently used in HHWSs around the world. The only other notable approach is the ÍCARO (Importância do Calor: Repercussão sobre os Óbitos [Importance of heat and its repercussions on mortality]) system in Portugal, which relies on epidemiologic assessment of mortality during unique heat wave events in that country and thus is not realistically applicable to other settings.24 Our study demonstrates that the triggering of alert days (and ultimately the initiation of emergency responses) depends on an HHWS's particular approach to establishing trigger values. We still have much to learn about the full array of factors that drive heat stress, including possible synergistic effects of air pollution,25 and how they may vary from place to place. Also, it is likely that demographic and societal changes and the introduction of heat protection measures will contribute to continuing modification of the heat-risk profile over time. How this may be translated into effective heat intervention strategies is not straightforward, but public health authorities and weather services responsible for the implementation of HHWSs should consider carefully the implications of adopting a particular trigger-setting approach and should also be aware of the need to periodically reevaluate trigger values. It is apparent that all the approaches we assessed could be further refined to improve performance. In addition, because each approach performed well in some settings but not in all, HHWSs might benefit from incorporating more than 1 trigger-setting procedure into their decisions.

It is sobering that we observed little agreement in the heat-alert days identified by the various trigger-setting methods currently in use in HHWSs. We recommend that future evaluations of HHWSs should assess not only health effects on days when alerts are triggered but also what may be being missed on days when they are not.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Health Canada. Shakoor Hajat was funded by a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellowship (076583/Z/05/Z).

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because no human volunteers participated in the study.

References

- 1.Semenza JC, Rubin CH, Falter KH, et al. Heat-related deaths during the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago. N Engl J Med 1996;335(2):84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klinenberg E. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosatsky T. The 2003 European heat waves. Euro Surveill 2005;10(7):148–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smoyer-Tomic KE, Rainham DG. Beating the heat: development and evaluation of a Canadian hot weather health-response plan. Environ Health Perspect 2001;109(12):1241–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilbourne EM. Heat-related illness: current status of prevention efforts. Am J Prev Med 2002;22(4):328–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard SM, McGeehin MA. Municipal heat wave response plans. Am J Public Health 2004;94(9):1520–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheridan SC, Kalkstein LS. Progress in heat watch–warning system technology. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 2004;85:1931–1941 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovats RS, Ebi KL. Heatwaves and public health in Europe. Eur J Public Health 2006;16(6):592–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthies F, Menne B. Prevention and management of health hazards related to heatwaves. Int J Circumpolar Health 2009;68(1):8–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalkstein LS, Jamason PF, Greene JS, Libby J, Robinson L. The Philadelphia hot weather–health watch/warning system: development and application, Summer 1995. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 1996;77:1519–1528 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan J, Kalkstein LS, Huang J, Lin S, Yin H, Shao D. An operational heat/health warning system in Shanghai. Int J Biometeorol 2004;48(3):157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascal M, Laaidi K, Ledrans M, et al. France's heat health watch warning system. Int J Biometeorol 2006;50(3):144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholls N, Skinner C, Loughnan M, Tapper N. A simple heat alert system for Melbourne, Australia. Int J Biometeorol 2008;52(5):375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jendritzky G, Bucher K, Laschewski G, Walther H. Atmospheric heat exchange of the human being, bioclimate assessments, mortality and thermal stress. Int J Circumpolar Health 2000;59(3–4):222–227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masterton JM, Richardson FA. A Method of Quantifying Human Discomfort Due to Excessive Heat and Humidity Downsview, Ontario, Canada: Environment Canada; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran DS, Pandolf KB, Shapiro Y, et al. An environmental stress index (ESI) as a substitute for the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT). J Therm Biol 2001;26(4–5):427–431 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steadman RG. A universal scale of apparent temperature. J Appl Meteorol 1984;23:1674–1687 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran DS, Epstein Y. Evaluation of the environmental stress index (ESI) for hot/dry and hot/wet climates. Ind Health 2006;44(3):399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons K. Heat stress standard ISO 7243 and its global application. Ind Health 2006;44(3):368–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebi KL, Teisberg TJ, Kalkstein LS, Robinson L, Weiher RF. Heat watch/warning systems save lives: estimated costs and benefits for Philadelphia 1995–98. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 2004;85:1067–1074 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheridan SC. A survey of public perception and response to heat warnings across four North American cities: an evaluation of municipal effectiveness. Int J Biometeorol 2007;52(1):3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouillet A, Rey G, Wagner V, et al. Has the impact of heat waves on mortality changed in France since the European heat wave of summer 2003? A study of the 2006 heat wave. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37(2):309–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosatsky T, King N, Henry B. How Toronto and Montreal (Canada) respond to heat. : Kirch W, Menne B, Bertollini R, Extreme Weather Events and Public Health Responses Darmstadt, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2005:167–171 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nogueira PJ. Examples of heat health warning systems: Lisbon's ICARO's surveillance system, summer of 2003. : Kirch W, Menne B, Bertollini R, Extreme Weather Events and Public Health Responses Darmstadt, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2005:141–159 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dear K, Ranmuthugala G, Kjellstrom T, Skinner C, Hanigan I. Effects of temperature and ozone on daily mortality during the August 2003 heat wave in France. Arch Environ Occup Health 2005;60(4):205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]