Abstract

Aim

Since few studies have examined the associations of plasma levels of coagulation factors II, V, IX, X, XI, XII, plasminogen, or α-2 antiplasmin with coronary heart disease (CHD), we sought to examine the associations of these factors with incident CHD in a prospective case-cohort study.

Methods

This case-cohort sample consisted of 368 African-American or white incident CHD cases that occurred between 1990–92 and 1998 in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, and a cohort random sample of n=412. Hemostatic factors were measured in the case-cohort sample using plasma stored at −70°C since 1990–92.

Results

After adjustment for age, sex and race, coagulation factors IX and XI, and α-2 antiplasmin were associated positively with risk of CHD: The hazard ratio [95% confidence interval] for the highest vs lowest quartiles was 1.52 [1.01–2.27] for factor IX; 2.26 [1.47–3.48] for factor XI; and 1.64 [1.05–2.57] for α-2 antiplasmin. However, these hemostatic factors were correlated with classical risk factors, so that after multivariable adjustment their associations with CHD were attenuated and no longer statistically significant. No associations were observed between CHD and factors II, V, X, XII, or plasminogen.

Conclusions

Positive associations of factors IX and XI, and α-2 antiplasmin with incident CHD were not strong and were accounted for by classical coronary risk factors. (213 words/250 limits)

Keywords: epidemiology, cardiovascular disease, ischemic disease, fibrinolytic factors, blood clotting

INTRODUCTION

Associations of several hemostatic factors, such as fibrinogen, factors VII and VIII, von Willebrand factor, tissue plasminogen activator antigen, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, with risk of atherosclerotic diseases have been widely examined1).The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study reported that fibrinogen, factor VIII, von Willebrand factor and plasminogen were associated positively, but only fibrinogen strongly and independently, with risk of coronary heart disease (CHD)2,3). Factors II, V, IX, X, XI and XII are also involved in formation of thrombi, and plasminogen and α-2 antiplasmin play roles in fibrinolysis. These factors have been hypothesized to be risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and some have been associated with venous thrombosis1). However, their prospective associations with CHD have been less thoroughly studied. We thus conducted a case-cohort study to examine the association of these novel hemostatic factors (coagulation factors II, V, IX, X, XI, XII, plasminogen and α-2 antiplasmin) with risk of incident CHD in ARIC. Most of these factors have not yet been examined previously in ARIC2,3) or other prospective studies of CHD occurrence. The a priori hypothesis was that these factors would be associated with increased risk of CHD, independently of classical risk factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The ARIC Study comprised a community-based sample of 15,792 persons from 4 centers: Forsyth County, North Carolina; the city of Jackson, Mississippi; northwestern suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Washington County, Maryland. Participants were 45 to 64 years of age during the baseline period (visit 1: 1987 to 1989). The ARIC study protocol was approved by each field center’s institutional review board. After written informed consent was obtained, participants underwent a baseline clinical examination. Re-examinations were performed every 3 years, up to 9 years. Details of the ARIC study protocol were described elsewhere4).

Incident CHD

Participants were followed for incident cardiovascular events through 1998 via annual telephone contact and surveillance of hospital and death records. For patients hospitalized with a potential myocardial infarction, trained abstractors recorded the presenting symptoms and related clinical information, including cardiac biomarkers, and photocopied up to three 12-lead ECGs for Minnesota coding. Out-of-hospital deaths were investigated by means of death certificates and, in most cases, by an interview with one or more next of kin and a questionnaire filled out by the patient's physician. Coroner reports or autopsy reports, when available, were abstracted for use in validation. A CHD event was defined as a validated definite or probable hospitalized myocardial infarction, a definite CHD death, a silent myocardial infarction by electrocardiogram, or a coronary revascularization. The criteria for definite or probable myocardial infarction were based on combinations of chest pain symptoms, ECG changes, and cardiac biomarker levels5,6). The criteria for definite fatal CHD were based on chest pain symptoms, history of CHD, underlying cause of death from the death certificate, and any other associated hospital information or medical history, including that from an ARIC clinic visit6). Stable or unstable angina pectoris were not captured as a CHD event.

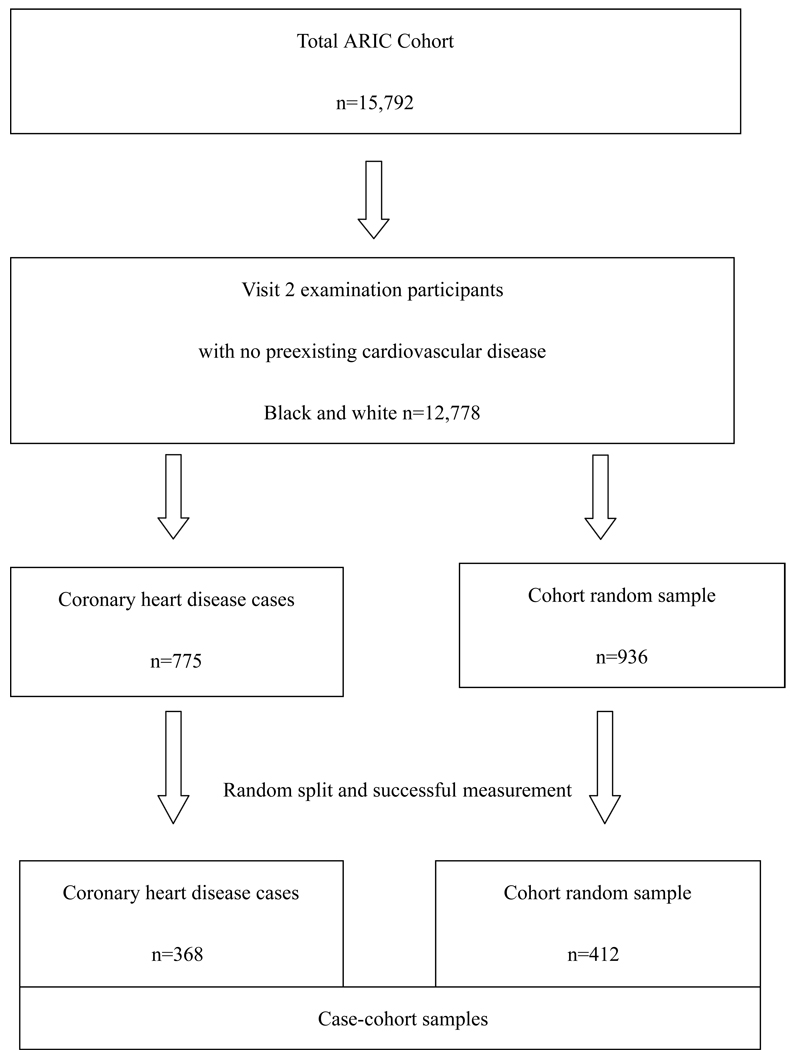

Case-cohort design

A case-cohort design was employed to study prospective associations between parameters measured in stored blood specimens at ARIC visit 2 (1990–1992) and subsequent cardiovascular events (CHD and stroke). Subjects were excluded if they had not participated in visit 2 examinations; if they had preexisting CHD or a transient ischemic attack/stroke before the visit 2 examination or were missing information on CHD history. Due to small numbers, we also excluded subjects whose race was neither white nor American-African, or if they were African-American in the Washington County or Minneapolis field center (total n=3,014 excluded).

Incident cardiovascular events were identified from visit 2 through Dec 31st, 1998 (median follow-up =7.5 years). A total of 775 CHD events were identified during follow-up. A stratified cohort random sample (CRS) of 936 participants was selected from the eligible ARIC cohort (n=12,778). Stratification was done by age (<55 or ≥55 years), sex and race (African-American or white). The number of subjects sampled in each stratum related to the number of incident CHD cases in that stratum from visit 2 examination through 1997. That is, in the two age-strata for white males the CRS numbers drawn were equal to the number of CHD cases in the strata, but in the other 6 strata the CRS numbers drawn were twice the number of CHD cases. Therefore some strata were oversampled, and thus we weighted each stratum of the CRS by the reciprocals of the sampling rates. The list of cases and the CRS was randomly sorted and split into two roughly equal parts. One part was selected to have hemostatic factors measured, and we successfully obtained values for 85%. In the end, 368 incident CHD events and 412 CRS subjects (including 25 CHD events in persons selected in the CRS) were included in this case-cohort study. Those included were not significantly different from those not included on major risk factors. Likewise, the CRS had largely identical risk factor levels as the whole ARIC cohort.

Measurements

Blood sample was collected at the visit 2 examination into sodium citrate anticoagulant tubes. Centrifuged plasma was stored at −70°C storage freezers until analyzed. After selection of cases and the CRS, stored plasma vials were retrieved from freezers. Coagulation and chromogenic assays were performed on the ACL9000 instrument (Instrumentation Laboratory Co, Lexington, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Coagulation factors II, V, IX, X, XI, XII were measured using corresponding factor deficient plasmas and either a high sensitivity rabbit brain thromboplastin (IL Test PT-Fibrinogen HS) or aPTT reagent (rabbit brain phospholipids and silica; IL Test aPTT-C Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time). Plasminogen and α-2 antiplasmin were measured by automated chromogenic assays (IL Test Plasminogen and IL Test plasmin inhibitor) using a synthetic chromogenic substrate S-2403. Calibration Plasma (Assess Calibration Plasma, Instrumentation Laboratory, Barcelona, Spain) was used for the quantitation of coagulation and chromogenic tests, and standardized normal control plasma (Assess Normal Control, Instrumentation Laboratory, Barcelona, Spain) was used for quality control. To test repeatability of measurements, we split 46 samples after blood drawing into pairs and separately processed, stored and blindly analyzed them. The reliability coefficients between paired measurements were 0.75 for factor II; 0.68 for factor V; 0.82 for factor IX; 0.68 for factor X; 0.90 for factor XI; 0.89 for factor XII; 0.86 for plasminogen; and 0.65 for α-2 antiplasmin.

Sitting blood pressure at the visit 2 examination was measured three times using a random-zero sphygmomanometer after five minutes rest and the mean of the last two measurements was used for analysis. Use of antihypertensive or cholesterol lowering medications within the two weeks before visit 2 interview was self-reported. Fasting plasma total, low and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations were measured by enzymatic methods. Diabetes mellitus was defined at baseline as a fasting glucose ≥126mg/dL, nonfasting glucose ≥200mg/dL, a history of physician-diagnosed diabetes, or use of diabetes medication. Cornell voltage was calculated by | S V3 | + R aVL on the baseline ECG, and Cornell voltage >28mV for men and >22mV for women was considered to reflect left ventricular hypertrophy. Smoking and drinking status (current, ex-, or never smokers or drinkers), usual alcohol intake, menopausal status, and current use of salicylates (including salicylate combinations), coumarin and hormone replacement therapy, were derived from interviews. Body mass index (kg/m2) was computed from weight in a scrub suit and standing height. Waist-hip ratio was calculated by the girth of the waist divided by the girth of the hips. Education level and sports index were derived from visit 1 interviews. Sports index represented sports during leisure time, based on the ARIC/Baecke questionnaire described elsewhere7). Pre-existing CHD at the visit 2 examination was defined by self-reported prior physician diagnosis of myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, or by prevalent myocardial infarction by 12 lead electrocardiogram, or by an incident myocardial infarction between visits 1 and 2. Pre-existing transient ischemic attack/stroke was defined by any self-reported physician diagnosis of transient ischemic attack or stroke at visit 1 or by an incident stroke between visits 1 and 2.

Statistical analysis

Unadjusted means or prevalences of baseline characteristics were computed for CHD cases and the CRS. For the CRS, mean values and prevalences were weighted according to the sampling fractions of sampling strata. We categorized subjects into quartiles of each hemostatic factor based on the distribution in the CRS. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of CHD in relation to quartiles were calculated using proportional hazard models, with Barlow’s methods8) to account for the case-cohort design. Trends across the quartiles were tested employing the median value for each quartile. Increments in HR and 95%CI for 1-standard deviation difference in hemostatic factors were calculated by fitting the factors as standardized linear independent variables. Adjustment was made for age (continuous), sex, race (white or African-American), and other Framingham risk factors, i.e., systolic blood pressure (continuous), antihypertensive medication use (yes, no), plasma total and HDL-cholesterol (continuous), diabetes status (yes, no) and smoking status (never, ex-, or current). As supplementary analyses, further adjustment for other cardiovascular risk factors, i.e. electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy (yes, no), waist-hip ratio (continuous) and drinking status (non-current or current) was performed. In the CRS, unweighted Spearman correlation coefficients were computed for each hemostatic factor with systolic blood pressure, plasma total and HDL-cholesterol, waist-hip ratio, gender, race, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, current smoking and current drinking. Adjusted R2 values were calculated for multiple regression models containing each hemostatic factor as a dependent variables and risk factors, age and antihypertensive medication use as the independent variables. All probability values for statistical tests were two-tailed and values of p<0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

As table 1 shows, visit 2 systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, diabetes and current smoking were higher among cases than the CRS. There was no difference in mean levels of hemostatic factors between cases and the CRS.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of men and women aged 47–68 in the ARIC case-cohort sample.

| Cohort Random Sample (n=412) |

CHD events (n=368) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | Mean (SD†) or percent |

Mean (SD) or percent |

| Age, y | 56.9 (5.4) | 58.4 (5.4) |

| Male, % | 41.9 | 67.4*** |

| African American, % | 24.0 | 21.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 121.4 (18.7) | 130.5 (21.6)** |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72.3 (10.8) | 74.5 (11.0) |

| Antihypertensive medication, % | 29.9 | 41.6 |

| Plasma total cholesterol, mg/dl | 206.7 (38.4) | 221.2 (41.9)* |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 131.1 (36.1) | 147.5 (37.0)** |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dl | 50.4 (16.8) | 41.2 (12.8)*** |

| Cholesterol lowering medication, % | 5.5 | 6.8 |

| Diabetes, % | 15.9 | 26.8* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.1 (5.7) | 28.6 (5.0) |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.92 (0.08) | 0.96 (0.06)*** |

| ECG left ventricular hypertrophy, % | 2.2 | 4.4 |

| Current smoker, % | 17.4 | 30.8* |

| Current drinker, % | 59.1 | 49.6 |

| Alcohol intake, g/week | 31.7 (100.4) | 33.3 (92.9) |

| Sports index | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.7) |

| Education (> high school graduate), % | 47.2 | 37.9 |

| Salicylate use, % | 27.1 | 31.5 |

| Coumarin use, % | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Premenopausal, % among women | 7.9 | 5.0 |

| Hormone use, % among women | 28.5 | 17.7 |

| Factor II, % | 99.6 (11.9) | 99.5 (16.6) |

| Factor V, % | 105.4 (33.6) | 108.9 (32.0) |

| Factor IX, % | 88.5 (29.3) | 92.5 (33.1) |

| Factor X, % | 102.9 (25.8) | 101.4 (32.1) |

| Factor XI, % | 84.1 (19.7) | 86.9 (20.7) |

| Factor XII, % | 78.8 (24.0) | 74.7 (23.7) |

| α-2 antiplasmin, % | 97.7 (12.9) | 98.3 (10.7) |

| Plasminogen, % | 116.1 (14.0) | 115.0 (14.8) |

25 people overlap between the CRS and event groups.

Due to some missing data, sample size ranged 397–412 for the CRS and 354–368 for the CHD event group.

Unweighted standard deviations presented to make comparable with events.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 for difference from the CRS.

Table 2 shows multivariate adjusted HRs of CHD according to quartiles of each hemostatic factor. In the age, sex and race-adjusted model, several factors were positively associated with CHD, namely, factor IX (the HR for the highest vs lowest quartiles = 1.52 [1.01–2.27], p for trend =0.05), factor XI (2.26 [1.47–3.48], p for trend =0.001) and α-2 antiplasmin (1.64 [1.05–2.57], p for trend =0.006). Although the trend across the quartiles of factor V did not reach statistical significance, the HR for 1-standard deviation was statistically significant for factor V, as well as factors IX and XI, and α-2 antiplasmin. All these associations, however, were attenuated and no longer statistically significant after adjustment for Framingham risk factors (the HR for the highest vs lowest quartiles =0.93 [0.56–1.54], p for trend =0.57 for factor IX; 1.27 [0.73–2.21], p for trend =0.59 for factor XI; and 0.81 [0.45–1.47], p for trend =0.81 for α-2 antiplasmin). These results were unchanged when we further adjusted for electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy, waist-hip ratio and drinking status (data not shown). No significant associations were observed between factors II, X, XII, or plasminogen and incident CHD.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) of coronary heart disease, ARIC case-cohort sample.

| Quartiles of hemostatic factors | HR for 1-SD increase |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (low) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (high) | P for trend | |||

| Factor II, % | 9.38–92.2 | 92.3–99.9 | 100–106 | 107–201 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 736 | 761 | 715 | 784 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 91 | 101 | 76 | 100 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.15 (0.76–1.72) | 1.03 (0.67–1.59) | 1.36 (0.89–2.07) | 0.20 | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 0.77 (0.46–1.29) | 0.91 (0.55–1.52) | 0.89 (0.50–1.60) | 0.89 | 0.96 (0.75–1.22) | |

| Factor V, % | 13.3–84.1 | 84.2–109 | 109–128 | 128–202 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 764 | 726 | 666 | 732 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 84 | 90 | 85 | 100 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.12 (0.74–1.71) | 1.39 (0.90–2.14) | 1.32 (0.87–2.00) | 0.13 | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 0.86 (0.51–1.45) | 1.28 (0.76–2.15) | 1.22 (0.74–2.02) | 0.25 | 1.15 (0.96–1.38) | |

| Factor IX, % | 17.6–71.8 | 71.9–87.2 | 87.3–105 | 106–250 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 784 | 741 | 746 | 726 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 94 | 86 | 81 | 106 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.68–1.55) | 0.96 (0.63–1.45) | 1.52 (1.01–2.27) | 0.05 | 1.26 (1.09–1.47) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.64–1.65) | 0.54 (0.32–0.91) | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) | 0.57 | 1.06 (0.89–1.27) | |

| Factor X, % | 6.86–85.9 | 86.0–99.8 | 99.9–112 | 113–331 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 763 | 749 | 750 | 735 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 102 | 89 | 94 | 83 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 0.97 (0.65–1.46) | 1.03 (0.69–1.54) | 0.99 (0.66–1.49) | 0.97 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 0.72 (0.43–1.20) | 0.76 (0.46–1.25) | 0.61 (0.36–1.03) | 0.10 | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | |

| Factor XI, % | 36.1–69.6 | 69.7–82.5 | 82.6–96.2 | 96.3–182 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 768 | 763 | 724 | 743 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 62 | 110 | 91 | 104 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.91 (1.25–2.92) | 1.86 (1.20–2.90) | 2.26 (1.47–3.48) | 0.001 | 1.30 (1.13–1.51) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.51 (0.91–2.50) | 1.52 (0.91–2.55) | 1.27 (0.73–2.21) | 0.59 | 1.14 (0.95–1.38) | |

| Factor XII, % | 15.7–61.5 | 61.6–77.4 | 77.5–91.9 | 92.0–157 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 749 | 741 | 717 | 790 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 110 | 100 | 73 | 84 | |||

| Model 1 | Model 1 | 1.0 | 0.88 (0.59–1.31) | 0.68 (0.44–1.04) | 0.78 (0.52–1.19) | 0.15 | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.26 (0.77–2.07) | 0.83 (0.49–1.40) | 1.17 (0.70–1.94) | 0.84 | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | |

| α-2 antiplasmin, % | 35.3–91.3 | 91.4–98.4 | 98.5–105 | 106–136 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 783 | 756 | 778 | 680 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 76 | 94 | 122 | 76 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.37 (0.90–2.10) | 2.10 (1.38–3.19) | 1.64 (1.05–2.57) | 0.006 | 1.27 (1.08–1.48) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.16 (0.70–1.91) | 1.69 (1.02–2.78) | 0.81 (0.45–1.47) | 0.81 | 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Plasminogen, % | 62.7–106 | 106–116 | 117–125 | 125–159 | |||

| CRS (person-years) | 748 | 797 | 736 | 715 | |||

| CHD events* (n) | 99 | 97 | 81 | 91 | |||

| HR (95%CI) | Model 1 | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.70–1.56) | 1.12 (0.73–1.73) | 1.47 (0.95–2.27) | 0.09 | 1.12 (0.96–1.31) |

| Model 2 | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.64–1.60) | 0.89 (0.53–1.48) | 0.81 (0.45–1.45) | 0.44 | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) | |

Events include 25 people overlapping between the CRS and event groups.

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex and race

Model 2: further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total and HDL-cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking status. Subjects with missing covariates were eliminated from model 2 analyses (14 eliminated).

SD: standard deviation; CRS: cohort random sample; CHD coronary heart disease; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval

To interpret these findings, we computed Spearman correlation coefficients of each hemostatic factor with classical risk factors (Table 3). As expected, each factor was correlated modestly with several classical risk factors. For example, factor IX was correlated r =0.15 with systolic blood pressure, r =0.13 with waist-to-hip ratio and r =0.26 with diabetes. Factor XI was correlated r =0.14 with total cholesterol and r =0.22 with diabetes. R2 values for multiple regression models including the classical risk factors were 0.10 for factor II, 0.11 for factor IX, 0.09 for factor XI, 0.08 for α-2 antiplasmin and 0.16 for plasminogen. All of these factors were correlated with each other (r>0.14), and the correlation was especially strong between factors IX and XI (r=0.63).

Table 3.

Unweighted Spearman correlation coefficients (r) of hemostatic factors with classical risk factors, ARIC cohort random sample.

| Continuous |

Dichotomous |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | Total cholesterol |

HDL- cholesterol |

WHR | Male gender |

AA race |

Diabetes | LVH | Current smoking |

Current drinking |

adjusted R2 |

|

| Factor II | −0.02 | 0.25*** | 0.21*** | −0.04 | −0.16*** | 0.11* | −0.01 | 0.10* | 0.14** | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Factor V | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.11* | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| Factor IX | 0.15** | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.13** | −0.11* | 0.12* | 0.26*** | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.11 |

| Factor X | 0.03 | 0.21*** | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.12* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12* | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Factor XI | 0.07 | 0.14** | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.17*** | 0.08 | 0.22 *** | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.09 |

| Factor XII | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.10* | −0.11* | −0.19*** | −0.14** | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| α-2 Antiplasmin | 0.12* | 0.12* | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.26*** | 0.03 | 0.15** | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| Plasminogen | 0.11* | 0.26*** | 0.16** | 0.03 | −0.26*** | 0.24*** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.16 |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; HDL: high density lipoprotein; WHR: waist-hip ratio; AA: African-American; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy

Independent variables for R2: age, sex, race, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total and HDL-cholesterol, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, waist-hip ratio, smoking and drinking status

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Further adjustment for salicylates and hormone replacement therapy did not change the results (excluding 52 people missing hormone therapy). There were only 5 people who had used coumarin at the Visit 2 examination (4 in CHD cases and 1 in the CRS). Excluding these people did not affect the results. Similarly, when we excluded premenopausal women (n=17 excluded), the results were virtually unchanged (data not shown). Furthermore, when we used a hard endpoint (i.e., hospitalized myocardial infarction plus fatal CHD only) as the outcome (number of cases =218), these trends were similar; no significant association after multivariate adjustment.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study, factors IX and XI and α-2 antiplasmin were associated positively with incident CHD, but these associations were non-significant after adjustment for classical coronary risk factors. The hemostatic factors were correlated with several classical risk factors, so the associations of these hemostatic factors with CHD were confounded by these risk factors. No significant associations across quartiles were observed for factors II, V, X, XII, or plasminogen with incident CHD.

Few previous studies have examined the associations between these hemostatic factors and incident CHD. In a previous nested case-control study of the Cardiovascular Health Study, no association was found between prothrombin (factor II) levels and incident or prevalent myocardial infarction9). Small case-control studies (n=22 to 300) suggested that factors V and XI were possibly associated with CHD10–12), and factors II, X, and XII were not10,11), generally consistent with our findings. No study had examined the association of factors IX or α-2 antiplasmin activations with incident CHD in the general population, to our knowledge. Factor IX activation peptide, factor XIa-C1 inhibitor, and factor XI-α1-antitripsin complexes – markers of activation of factor IX or XI – have been reported to be associated with CHD13,14). Taken together, the hemostatic factors we examined here were not independently associated with incident CHD.

A prior case-cohort study in ARIC (follow-up from 1987 to 1993)3) suggested that, although the association was nonlinear, a high level of plasminogen carried an elevated risk of incident CHD; HR =2.2 (1.2–4.2) for the highest vs lowest quintile. This was not replicated in the present study, due possibly to a large proportion of events later in follow-up (events occurring in the first year composed 9% in the present study compared with 19% in the prior ARIC report). The prior ARIC report suggested that the association for plasminogen was more prominent with early CHD events3).

Our observation did not support the hypothesis that these factors are independently associated with increased risk of CHD. That is, the association of coagulation factors IX and XI and α-2 antiplasmin with incident CHD, which we observed only in age, sex and race-adjusted models, seemed to reflect the association of these three factors with other classical risk factors for CHD. Thus, measuring these factors would have little impact for preventive cardiology, since this would add little benefit beyond classical risk factors in predicting CHD. Nevertheless, associations of factors IX and XI, and α-2 antiplasmin found in the age, sex and race-adjusted model might reflect possible mechanistic roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis.

Limitations of this study warrant discussion. First, the sample size was not large, although larger than most prior case-control studies. Given our CRS size (n=412), we could detect HR>1.6 between any two quartiles at 81% power. True associations weaker than HR=1.6, if any, may have been missed, but we did not find any estimates close to HR≈1.6 between the highest and lowest quintiles; that is, all multivariable-adjusted associations were 1.27 or less. This would be a weak association whether it was statistically significant or not. Therefore, our conclusions may not be affected greatly by our sample size, although the results should be interpreted cautiously. Second, we split the original CRS into two parts to reduce measurement cost. This limited our statistical power, but we believe this process was statistically valid, because the splitting was done after random sorting of the sampling list. Third, it is possible that our findings were basically negative due to measurement error. Having only a single measurement for each analyte may have obscured real associations. Also, the measurement repeatability was only modest for factors II, V, X and α-2 antiplasmin. Moreover, although the samples were stored at −70°C, we could not confirm the repeatability of measurements over the long sample preservation time (more than 10 years). Therefore, the null results presented here need to be confirmed by further studies.

In conclusion, higher levels of factors IX and XI, and α-2 antiplasmin were associated with increased risk of CHD, but not independent of other coronary risk factors.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of study sample selection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND NOTICE OF GRANT SUPPORT

The ARIC Study is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-55015, 55016, 55018, 55019, 55020, 55021, and 55022. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC Study for their important contributions. Kazumasa Yamagishi was supported by the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowe GDO. Can haematological tests predict cardiovascular risk? The 2005 Kettle Lecture. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:232–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folsom AR, Wu KK, Rosamond WD, Sharrett AR, Chambless LE. Prospective study of hemostatic factors and incidence of coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 1997;96:1102–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folsom AR, Aleksic N, Park E, Salomaa V, Juneja H, Wu KK. Prospective study of fibrinolytic factors and incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:611–617. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Operations Manual No. 3: Surveillance Component Procedures: Version 1.0. Chapel Hill: ARIC Coordinating Center, School of Public Health, University of North Carolina; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years' experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:685–693. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smiles AM, Jenny NS, Tang Z, Arnold A, Cushman M, Tracy RP. No association of plasma prothrombin concentration or the G20210A mutation with incident cardiovascular disease: Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:614–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redondo M, Watzke HH, Stucki B, Sulzer I, Biasiutti FD, Binder BR, Furlan M, Lammle B, Wuillemin WA. Coagulation factors II, V, VII, and X, prothrombin gene 20210G-->A transition, and factor V Leiden in coronary artery disease: high factor V clotting activity is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1020–1025. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merlo C, Wuillemin WA, Redondo M, Furlan M, Sulzer I, Kremer-Hovinga J, Binder BR, Lammle B. Elevated levels of plasma prekallikrein, high molecular weight kininogen and factor XI in coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161:261–267. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berliner JI, Rybicki AC, Kaplan RC, Monrad ES, Freeman R, Billett HH. Elevated levels of Factor XI are associated with cardiovascular disease in women. Thromb Res. 2002;107:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(02)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnema MC, Peters RJG, de Winter R, Lubbers YPT, Barzegar S, Bauer KA, Rosenberg RD, Hack CE, ten Cate H. Activation of clotting factors XI and IX in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2489–2493. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller GJ, Ireland HA, Cooper JA, Bauer KA, Morrissey JH, Humphries SE, Esnouf MP. Relationship between markers of activated coagulation, their correlation with inflammation, and association with coronary heart disease (NPHSII) J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:259–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]