Abstract

In order to discriminate conductive hearing loss from sensorineural impairment, quantitative measurements were used to evaluate the effect of artificial conductive pathology on distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs), auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) and laser Doppler vibrometry (LDV) in mice. The conductive manipulations were created by perforating the pars flaccida of the tympanic membrane, filling or partially filling the middle-ear cavity with saline, fixing the ossicular chain, and interrupting the incudo-stapedial joint. In the saline-filled and ossicular-fixation groups, averaged DPOAE thresholds increased relative to the control state by 20 to 36 dB and 25 to 39 dB respectively with the largest threshold shifts occurring at frequencies less than 20 kHz, while averaged ABR thresholds increased 12 to 19 dB and 12 to 25 dB respectively without the predominant low-frequency effect. Both DPOAE and ABR thresholds were elevated by less than 10 dB in the half-filled saline condition; no significant change was observed after pars flaccida perforation. Conductive pathology generally produced a change in DPOAE threshold in dB that was 1.5 to 2.5 times larger than the ABR threshold change at frequencies less than 30 kHz; the changes in the two thresholds were nearly equal at the highest frequencies. While mild conductive pathology (ABR threshold shifts of < 10 dB) produced parallel shifts in DPOAE growth with level functions, manipulations that produced larger conductive hearing losses (ABR threshold shifts > 10 dB) were associated with significant deceases in DPOAE growth rate. Our LDV measurements are consistent with others and suggest that measurements of umbo velocity are not an accurate indicator of conductive hearing loss produced by ossicular lesions in mice.

Keywords: Middle ear pathology, Distortion product otoacoustic emissions, Auditory brainstem responses, Umbo velocity, Mouse

1. Introduction

The middle ear is a passive, linear and time-invariant acoustico-mechanical system that transfers sound energy from the external ear to the inner ear (Békésy 1960; Zwislocki 1963; Rosowski 1994; Avan et al. 2000). Middle-ear pathology can alter sound transfer to the inner ear and result in conductive hearing loss, where the degree and frequency dependence of the conductive loss varies with different types of pathology (Pinsker 1972; Merchant and Rosowski 2003). The standard method for distinguishing conductive hearing loss in humans is a comparison of the individual's threshold sensitivity to air-conducted and bone-conducted sound, where an increase in the threshold to air-conducted sound that is greater than the increase in the threshold to bone-conducted sound in the same ear (an air-bone gap) is an indication of conductive hearing loss.

A number of mechanical and acoustical techniques, e.g., tympanometry (Margolis and Shanks 1985), ear canal sound power reflectance (Feeney et al. 2003; Allen et al. 2005) and laser-Doppler vibrometer measurements of tympanic membrane motion (Huber et al. 2003; Rosowski et al. 2008) have been suggested as objective measurements of conductive impairment, but none, by itself, has been demonstrated to be simply related to the degree of conductive hearing loss. The problems with these objective measurements of TM mobility is that the presence of the ossicular joints allows there to be significant motion of the TM even when the stapes is immobilized (Nakajima et al. 2005), and that pathologies that interrupt the ossicular chain produce a nonlinear relationship between TM and stapes motion, where TM motion is increased while stapes motion is reduced (Møller 1965; Allen 1986; Peake et al. 1992; Rosowski et al. 2008).

The problem of discriminating conductive from sensorineural hearing impairments is most troublesome in animal models of hearing loss in which behavioral audiometry is not an option. Several studies have used measurements of TM mobility (tympanometry, reflectance, laser-vibrometry) to estimate conductive impairment in animal models of various specific middle-ear pathologies, e.g. otitis media with effusion (e.g. Gan et al. 2006), as estimators of middle-ear changes in developing or ageing ears (Doan et al. 1994; Rosowski et al., 2003) or to compare conductive function in different genotypes (Yoshida et al. 2000; Samadi et al. 2005). However, as noted above, TM mobility in humans is not the best indicator of general conductive impairment, and one of the points of this paper is to evaluate TM mobility measurements in various artificial conductive impairments in mice. Sound-induced stapes motion would be a superior measure of conductive loss, but such measurements are highly invasive and are difficult to achieve in some animal species, e.g., mice (Saunders and Summers 1982). Measurements of bone-conduction driven physiological responses have been used to quantify the effects of different middle and inner-ear manipulations on hearing function in individual animals (Tonndorf and Tabor 1962; Tonndorf and Duvall 1966) but there are no standards for such responses in any animal model. Furthermore, bone-conduction studies in animals are complicated by the need for non-standard broadband bone-conduction stimulators, (Steel et al. 1987) and by the generation of significant sound energy by most available vibration sources.

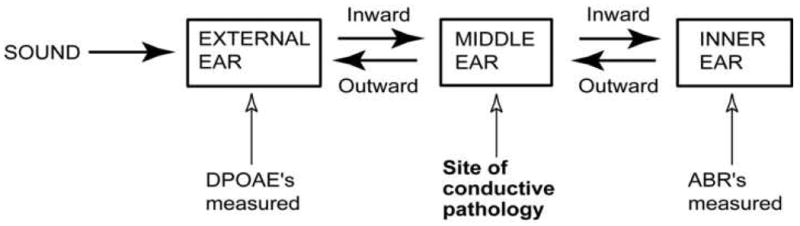

While controlled and standardized bone-conducted stimulation in animal models of hearing loss has been problematic (Steel et al. 1987), multiple non-invasive techniques have been used to quantify the hearing response produced by air-conducted sound in animals. Common techniques in use today include auditory brainstem response (ABR) and otoacoustic emission, especifically distortion-product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE), measurements (Kujawa and Liberman 1999; Parham et al. 2001; Maison et al. 2006; Zehnder et al. 2006). The contribution of middle-ear sound conduction to ABR and DPOAE generation is schematized in Figure 1, in which sound stimulus energy that passes through the external ear flows through the middle ear to the inner ear. The sensory processes within the inner ear give rise to both the synchronous synaptic activity that produces the ABR and the mechanical events that produce DPOAEs within the inner ear (Parham et al. 2001). Once generated within the inner-ear, the DPOAEs pass back through the middle ear and are measured within the external ear (Avan et al. 2000).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the flow of sound energy through the auditory periphery and the site of conductive pathology.

Figure 1 illustrates two significant differences in how the middle ear contributes to ABR and ear-canal DPOAE production. The first difference is that generation of ear-canal DPOAEs requires that sound energy passes through the middle ear twice, while it only passes through the middle ear once to generate ABRs. This asymmetry in the contribution of the middle ear suggests that middle-ear conductive impairments will produce larger effects on DPOAEs than ABRs.

The second difference is that whatever the contribution of the middle ear, it is generally thought to be a linear process, where alterations in middle-ear sound conduction should act as a simple change in the gain of the sound transfer function through the middle ear. On the other hand, the inner-ear processes that produce DPOAEs (as well as ABRs) are known to be nonlinear and saturating, and inner-ear pathology is expected to alter the growth rate and saturating values of DPOAEs (and ABRs) (Gehr et al. 2004). These differences in the effect of middle-ear conductive pathologies, and inner-ear sensorineural pathologies on DPOAE (and ABR) suggest that (a) The growth of an inner-ear response with stimulus level should be simply attenuated by conductive pathology, such that a simple increase in level will compensate for the pathology, and (b) Sensorineural pathology will affect the shape of the level-response function, altering the growth rate or the magnitude at saturation of DPOAEs and ABRs. The differences described above have been used to evaluate the presence of conductive impairments in several animal models. Gehr et al. (2004) and Janssen et al. (2005) suggested the use of observations of the growth of DPOAEs with stimulus level to separate conductive and sensorineural impairments, where simple horizontal shifts in growth with level functions are signs of conductive loss, while alterations in growth rate with level or value at saturation are signs of sensory loss. Zehnder et al. (2006), on the other hand, suggest that paired observations of the pathological changes in ABR and DPOAE threshold functions can help separate conductive pathology from sensory pathology, where sensory losses should produce equal changes in DPOAE and ABR thresholds, while conductive losses would have a larger effect on DPOAE thresholds.

Yet another method for using DPOAE growth to evaluate normal and pathologic auditory thresholds has been proposed by Boege and Janssen (2002). This method is observation-based rather than model-based, and uses a nonlinear transformation of measured DPOAE and stimulus levels to predict auditory thresholds in human patients and experimental animals. This approach recently has been generalized to distortion products visible in measurements of sound-induced umbo velocity that are produced by two-tone stimulation of the ear (Dalhoff et al. 1007; Turcanu et al. 2007, 2009).

The purpose of this report is to quantitatively compare different estimators of conductive impairment based on measurements of TM mobility, DPOAE growth functions, and comparisons of changes in ABR and DPAOE thresholds, so that we can test the efficacy of these estimators. Measurements of TM mobility, ABR and DPOAE thresholds, and DPOAE growth functions were made in young CBA/CAJ mice before and after middle-ear manipulations that produce conductive hearing loss.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals and Surgical preparation

CBA/CaJ mice (Jackson Lab, ME, USA) were investigated at 12 - 24 weeks of age in a terminal procedure to test either DPOAE and ABR or LDV. Mice were anesthetized (ketamine, 100 mg/kg i.p.; xylazine, 10 mg/kg i.p.), with booster injections 1/3 to 1/2 the original dose as needed, during all surgical and measurement procedures. Body temperature was monitored and maintained near 37°C by a combination of heating the air in the experimental chamber and a temperature controlled heating pad. In the ears used in LDV experiments, the cartilaginous external ear canal was removed to expose the pars tensa and pars flaccida of the tympanic membrane (TM). Only animals with normal appearing TMs are included in the mean measurements. Excessive cerumen was not observed in any experimental ear. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

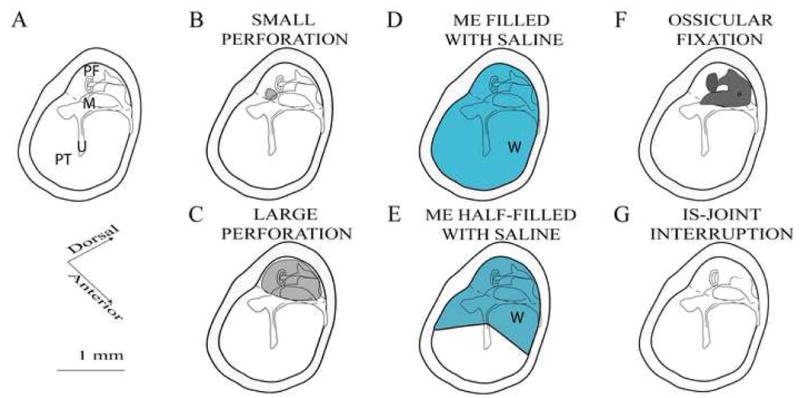

2.2 Experimental groups and conductive manipulations

Animals were split into two major experimental measurement groups, Group A: DPOAE and ABR measurements (n=36 ears), and Group B: TM-Velocity measurements (n=19 ears). Different sub-groups of each major group were used to measure the effects of different manipulations of the middle-ear system (Table 1) including: small and large perforations of the pars flaccida, the complete (filled) or half-filling of the middle-ear air space with physiological saline, ossicular chain fixations, and incudo-stapedial joint interruption (Figure 2). However, we report no ABR or DPOAE thresholds after incudo-stapedial joint interruption because we could measure no ABR or DPOAE response after interruption.

Table 1.

Experimental groups vs. manipulation and measurement procedures (ears)

| Groups | Manipulations | Measurements | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 1: Saline Filling | Control | Small Perforation | Saline Filled | Half Filled |

| DPOAE & ABR N=36 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| 2: Fixation | Control | Large Perforation | Ossicular Chain (OC) Fixation | ||

| 18 | 18 | 18 | 10 | ||

| Group B | Saline Filling | Small Perforation | Saline Filled | Half Filled | |

| LDV N=19 | 6 | Control 19 |

5 | 6 | 5 |

| Fixation + Interruption | Large Perforation | Ossicular Chain (OC) Fixation | + I-S joint Interruption | ||

| 13 | 11 | 8 | 5 | ||

Figure 2.

Schematics of the middle ear manipulations. A: The normal mouse middle ear with the larger pars tensa of the TM (PT), smaller pars flaccida (PF). The malleus (M) and umbo (U) are labeled. The incus and stapes (unlabeled) are posterior and dorsal to the malleus. B: The small gray circle in the PF shows the location of our small perforations. C: In large perforations, the PF is removed (the gray area). D: In the Saline-Filled condition a syringe is used to fill the entire ME with 3-4 microliters of saline via a separate perforation in the anterior PT. E: The Half-Filled condition is produced by wicking out about half of the water used to fill the middle ear. F: The Fixed Ossicular Chain (OC) condition results from the application of cyanoacrylic cement on the stapes, incus, posterior malleus and the posterior tympanic bone. G: The IS-joint is interrupted and the lenticular process of the incus removed.

The detailed procedures used to create the manipulation procedures follow.

Control: We placed a bead reflector on the tip of umbo for LDV measurement and did nothing for DPOAE and ABR measurement. We could see the intact, transparent tympanic membrane, a clear light cone and an aerated middle ear.

Perforation: For small perforations, we used a small hook to make a 0.2 mm diameter hole in the pars flaccida (Figure 2B). For large perforations, 90% or more of the flaccida was removed. Through the large perforation (Figure 2C), we could see the head of the malleus, the long process of the incus, incudo-stapedial joint, stapes crura and footplate.

Saline filling: Saline filling of the middle ear was always performed in ears with a small pars flaccida perforation. For the saline-filled condition, we filled the middle ear cavity with normal saline by puncturing the bottom of pars tensa with a fine needle and syringe and injecting saline until the water flowed out of the small pars flaccida hole (Figure 2D). The half-filled manipulation always followed the saline-filled condition. To reach the half-filled state, fine paper points placed through either the pars tensa perforation or small pars flaccida were used to absorb saline in the ventral part of the middle ear, so that saline filled the posterior dorsal middle ear down to the level of the umbo (Figure 2E). When the middle ear was filled with saline, the tympanic membrane became cloudy and protruded slightly into the ear canal causing a loss of the cone of light near the umbo. In the half-filled condition, an air-fluid line was observed at the umbo and the TM appeared cloudy posterior and dorsal to the umbo.

Fixation: Using a fine needle and syringe, we placed a small drop of cyanoacrylic liquid or surgical tissue glue on the footplate through the large hole in the pars flaccida. We would also place a larger drop of glue to fix the stapes, incus and anterior lamina of the malleus to the surrounding middle ear wall (Figure 2F).

Interruption: through the large perforation, we gently interrupted the incudo-stapedial joint using a small hook. We visually confirmed that the lenticular process of the incus and the head of stapes were separated from each other (Figure 2G).

2.2 Measurement of DPOAEs and ABRs

The DPOAE and ABR measurement methods are those of Maison et al. (2006). Stimuli were generated and delivered and responses monitored with A/D, D/A boards (National Instruments, Austin, TX), controlled by the LabVIEW programming environment. Two speakers were used to generate the two-tone DPOAE stimuli, and one of these was used to generate the ABR tone burst stimuli. An integrated probe-tube microphone monitored stimulus sound pressure and measured the DPOAE response. The sound stimuli were delivered to the ear canal using a coupler tip fitted within the opening of the ear canal to form a closed acoustic system. Sensitivity versus frequency calibration curves were generated for the probe microphone, enabling conversion from measured voltages to sound pressure levels.

The DPOAE stimuli consisted of two primary tones (f2:f1=1.2), presented with f2 level always 10 dB less than f1 level (L2=L1-10 dB) spanning the frequency range f2=5.6-45.2 kHz. Ear-canal sound pressures were filtered, amplified, digitized and Fast-Fourier transforms were computed from the averaged pressures. DPOAE detection threshold, defined as the lowest primary level that produces an emission level exceeding the noise floor by a criterion of 3 dB, were measured from an input-output (I/O) function.

ABRs were elicited using 5-ms tone pips (5.6-45.2 kHz; 0.5-ms rise/fall; cos2 shaping; 30/s). Responses were detected by subdermal needle electrodes, placed at the vertex (active), ventrolateral to the test ear (reference), and base-of tail (common), amplified (10,000 times), filtered (0.3-3kHz bandpass), and averaged (512 sweeps at each frequency level combination; artifact reject = 15-μV peak to peak). ABR “thresholds” were defined as the lowest sound level at which response peaks were clearly present.

2.3 Laser-Doppler Vibrometry

Umbo velocity was measured with a laser-Doppler vibrometer in response to tones of frequencies from 1 to 50 kHz. A small (20-50 μm diameter) reflective bead was placed on the umbo. An open-backed sound coupler-attached to a DT-48 earphone by an 8 cm long rubber tube was sealed over the ear canal opening and the beam of a Polytec laser vibrometer was focused on the bead. The output of the vibrometer was averaged synchronously during repetitive acoustic stimulation (n=500 to 2000). After multiple repeated measurements of umbo velocity (Vu), the laser was turned off and a probe-tube coupled to a 1/4 inch microphone was placed in the coupler, such that the opening of the probe was positioned within the opening of the bony canal. The sound stimulus was restarted and the output of the microphone was averaged during 500 to 1000 repeated stimuli. An independently determined probe-tube transfer function was used to convert the measured microphone voltage to sound pressure (Pec), and the Umbo-Velocity Transfer Function (Hu) was computed as the ratio of the measured velocity and ear-canal pressure: (Hu = Vu / Pec) (Rosowski et al. 2003).

2.4 Statistical analyses of the effects of the manipulations on the measured quantities

The basic break out of the different experimental groups is described in Table 1. There were three groups of control animals each used in separate experimental series. The first two groups (of 18 animals each) were used in measurements of DPOAE and ABR thresholds before and after different middle-ear manipulations. In group A1 DPOAE and ABR thresholds were measured in one ear from each of 18 control animals. We successfully produced a small perforation of the pars flaccida in 15 of these ears; DPOAE and ABR measurements were repeated after perforation. Eight of these ears were then filled with saline before repeating the threshold measurements while the remaining seven ears were half-filled with saline before repeated measurements. Unpaired t-tests with unequal variance were performed between the 18 control ears, the 15 small-perforation ears, the 8 saline-filled ears and the 7 half-filled ears at each of the seven test frequencies without Bonferroni corrections. We also performed two-way nested ANOVA analyses (with frequency and ear-condition as parameters) of paired groupings of control and manipulated ears (e.g. the eight measurements in the saline-filled ears were compared with the control measurements in those same eight ears). The two statistical tests gave similar results. Similar testing was performed in Group A2 where DPOAE and ABR thresholds were measured in 1 ear from 18 control mice before and after a large perforation was introduced in pars flaccida, and after using glue to fix the ossicular chain to the bony middle-ear wall. The placement of the glue, without also gluing the TM, was performed successfully in 10 of the 18 ears.

The third group (Group B) of 19 ears was used in the laser Doppler vibrometer measurements of umbo velocity. Of these 19 control ears, 6 were used in saline-filling measurements in which vibrometry was performed after placing a small perforation in pars flaccida in 5 ears, after complete saline filling in all of the 6 ears, and after half-filling in 5 ears. In the 13 ossicular manipulation ears, a large perforation of the pars flaccida was successfully performed in all ears, but vibrometer measurements were only performed after this manipulation in 11 ears. In eight of the 13 ears vibrometry was repeated after using glue to fix the ossicular chain, while vibrometry was performed in the remaining 5 ears after I-S joint interruption. Statistical comparisons using unpaired t-tests with unequal variance were performed between the different groups at each of the test frequencies without Bonferroni corrections. Two-way nested ANOVA analyses (with frequency and ear-condition as parameters) of paired groupings of control and manipulated ears were also performed, and the two statistical tests gave similar results.

3. Results

3.1 Experimental Group A: DPOAE and ABR threshold shifts caused by conductive pathology

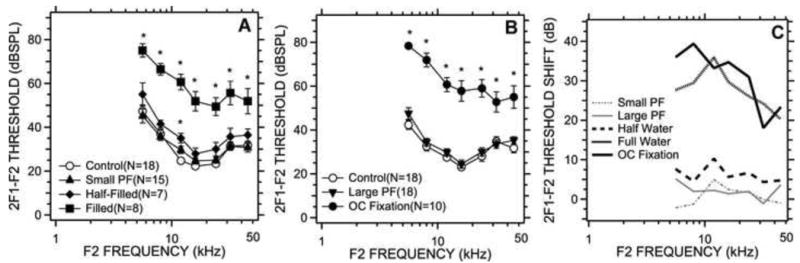

We measured the DPOAE thresholds before and after pars flaccida perforation, middle ear saline filling (full and half level) and ossicular chain fixation. Figures 3A & B compare the mean and standard error of the mean of DPOAE thresholds in the control, post pars flaccida perforation, post saline filling and post ossicular chain fixation in two different manipulation sub-groups respectively. Middle-ear saline filling and ossicular fixations produced elevations in the mean DPOAE thresholds at all frequencies; however, there was no obvious threshold change after pars flaccida perforation (either by a small hole or large hole). While the mean DPOAE thresholds with half-saline filling were slightly elevated compared to the control condition, our t-tests suggested these two populations were only statistically separable at 12 kHz (a t-test comparing the two sets at 12 kHz yielded a p<0.01), while the paired two-way nested ANOVA suggested no significant effect of the half-saline filling. Significant differences were observed between full saline filling and control (t-tests suggested p<0.01 at all frequencies, and the ANOVA suggested a significant effect of manipulation at p < 0.001), ossicular chain fixation and control (t-tests suggested p<0.01 at all frequencies, and the ANOVA suggested a significant effect of manipulation at p < 0.001), as well as between full-water and half-water filling (t-tests at 8 kHz, 12 kHz, 16 kHz and 24 kHz suggested p<0.01, and p<0.05 at 5.6 kHz, 32 kHz and 45.2 kHz).

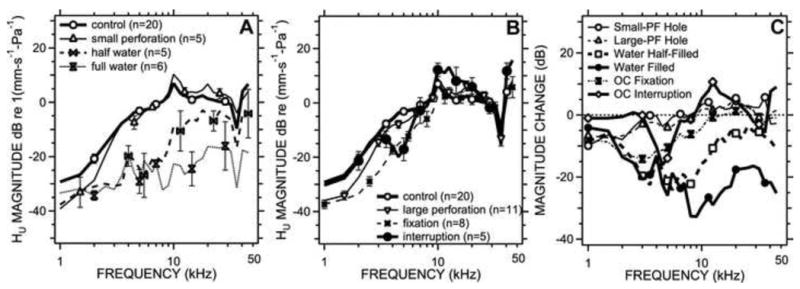

Figure 3.

DPOAE thresholds measured before and after middle-ear manipulation. 3A compares the mean DPOAE thresholds among control, small perforation of the pars flaccida, middle-ear half- and completely filled with saline states. Error bars in this and subsequent figures represent standard error of the mean (S.E.M). 3B compares the DPOAE thresholds (mean ± S.E.M) in the control, post large perforation of the pars flaccida and post ossicular chain (OC) fixation. 3C shows the mean changes in DPOAE threshold caused by the different manipulations. Points marked with a ‘*’ are significantly different from control based on t-tests of the data at each frequency.

Figure 3C shows the mean DPOAE threshold shifts caused by our conductive manipulations. The largest threshold shifts occurred at low frequency: In the saline filled group, thresholds increased by 20 to 36 dB with the largest increase at 12 kHz. In the ossicular-fixation group, threshold increases of 25 to 39 dB were observed with the largest increase at 8 kHz. The middle ears half-filled with saline showed threshold changes that are less than 10 dB at most frequencies, with the largest shift at 12 kHz. All of the ANOVA analyses suggested a significant effect of frequency (p < 0.001) on the measured DPOAE thresholds before and after manipulation.

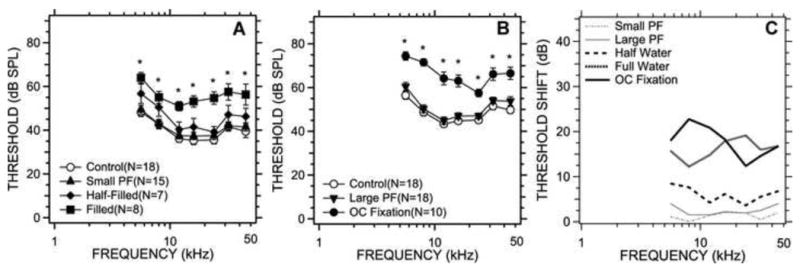

We measured ABR thresholds right after the DPOAE measurements. Figures 4A & B compare the mean ABR thresholds and the standard error of the mean among control, pars flaccida perforation, saline-filling and ossicular chain fixation groups. The middle-ear manipulations (with the exception of the pars flaccida perforations) elevated the average ABR thresholds at all frequencies. Similar to the DPOAE thresholds, pars flaccida perforation and the half-filled saline condition produced small elevations in the ABR thresholds (t-tests at all frequencies showed no significant changes from control, p>0.05, resulted from these manipulations). T-tests suggested significant threshold differences between full saline filling and control, and ossicular chain fixation and control at all frequencies (p<0.01), while ANOVA analyses also showed significant effects of these manipulations (p < 0.001). Significant differences were observed between full- and half-saline filling at 12 kHz, 16 kHz (p<0.05), and 24 kHz (p<0.01).

Figure 4.

ABR thresholds measured before and after middle-ear manipulation. 4A compares the ABR thresholds (mean ± S.E.M) among the control, small perforation of the pars flaccida, and the middle-ear half- and completely filled with saline states. 4B compares the ABR thresholds (mean ± S.E.M) in the control, post large perforation of the pars flaccida and post ossicular chain (OC) fixation. 4C illustrates the mean changes in ABR threshold caused by the different manipulations. Points marked with a ‘*’ are significantly different from control.

Figure 4C illustrates the ABR mean threshold shifts caused by all conductive manipulations. Large increases in threshold were observed in the saline-filled group (12dB to 19dB) and the ossicular fixation group (12dB to 25dB). The threshold increases in the half saline-filled group were less than 10 dB. No significant changes were observed in pars flaccida perforation conditions. The ABR threshold shifts in all conditions were relatively constant with frequency, and did not show the predominant low-frequency effect observed in the DPOAE threshold increases (Figure 3C).

3.2 experimental Group B: Umbo Velocity changes caused by conductive pathology

The Umbo Velocity Transfer Function, Hu, was measured before and after four different kinds of TM-Ossicular manipulations. Figure 5A shows the comparison of mean magnitudes and standard error of the mean in the normalized umbo velocity in the control, small perforation of the pars flaccida, the saline filled and half-filled conditions. The small perforation produced statistically insignificant decreases in mean magnitude of Hu at frequencies below 10 kHz and increases between 10 to 14 kHz when compared to control (p>0.05), and the ANOVA suggested the manipulation had an overall insignificant effect on the velocity (p> 0.10). Half-filling the middle ear with saline, resulted in significant mean magnitude reductions in Hu at frequencies 4 kHz, 8 kHz (p<0.01) and 2 kHz, 5.5 kHz, 16 kHz, 22.5 kHz (p<0.05), and the ANOVA suggested the effect of the manipulation was moderately significant (p < 0.025). The largest reductions produced by half-filling were at frequencies near 6 kHz and were about 20dB on average compared to control. Half-filling had smaller effects at frequencies above 10 kHz. Completely filling the middle ear with saline resulted in a significant decrease in Hu similar to half-filling at frequencies less than 10 kHz, and produced larger decreases of 15 to 30 dB on average above 10 kHz compared to control. The t-test at 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 5.5 kHz, 8 kHz, 11.5 kHz, 16 kHz, 22.5 kHz, 32 kHz, and 45.2 kHz frequencies indicated the differences between the complete saline-filling and control groups were significant (p<0.01), while the ANOVA suggested that complete saline filling had a highly significant effect on the measured velocity (p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

The magnitude of sound-driven umbo-velocity Hu before and after middle-ear manipulation. 5A compares the Hu magnitude (mean ± S.E.M) (in units of dB re 1 mm-s-1-Pa-1) in the control, small perforation of the pars flaccida, and middle-ear half- and completely filled with saline states. No significant differences were observed between control and the pars flaccida small perforation conditions; significant differences were observed between saline filling and control (p<0.01) at all frequencies, and half-filling and control (p<0.01 at 4 kHz, 8 kHz; p<0.05 at 2 kHz, 5.5 kHz, 16 kHz, and 22.5 kHz). 5B compares the TM-Velocity magnitudes (mean ± S.E.M) in the control, post large pars flaccida perforation and post ossicular chain fixation. Significant differences were observed between large pars flaccida perforation and control (p<0.01 at 2 kHz; p<0.05 at 5.5 kHz), ossicular fixation and control (p<0.01 at 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 5.5 kHz; p<0.05 at 8 kHz), as well as after ossicular interruption and control (p<0.01 at 4 kHz, 45.5 kHz; p<0.05 at 5.5 kHz, 11.5 kHz). 5C shows the mean TM-Velocity changes caused by pars flaccida perforation and half and complete saline filling of middle ear, as well as ossicular chain fixation.

We also measured umbo velocity transfer function in ears before and after manipulations of the ossicular chain. Figure 5B compares the mean magnitudes and standard error mean in Hu in the control condition and after: removing the pars flaccida, applying glue to the ossicular chain, and interrupting the incudo-stapedial joint. Removal of the pars flaccida produced larger changes than the small hole but only at the lowest frequencies (p<0.01 at 2 kHz; p<0.05 at 5.5 kHz). Gluing the ossicular chain to the cavity wall produced reductions in Hu magnitude of about 10 dB on average that were statistically significant at frequencies less than 10 kHz (p<0.01 at 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 5.5 kHz; p<0.05 at 8 kHz) and insignificant at higher frequencies. Interrupting the incudo-stapedial joint produced small repeatable frequency dependent increases and decreases in Hu magnitude that were significant at 4.5 kHz, 45.5 kHz (p<0.01) and at 5.5 kHz, 11.5 kHz (p<0.05), however, the mean magnitude changes compared to control were generally less than 10 dB. The nested ANOVA performed found no significant differences between the velocity in the control state and that measured after any of these three manipulations.

The mean changes in Hu that were produced by our manipulations are illustrated in Figure 5C. Introduction of either a small hole in the pars flaccida of the TM or removal of the entire pars flaccida had only a small effect on average Hu (change of less than 9 dB, with the biggest changes at the lowest frequencies). Fixation of the ossicles resulted in Hu magnitudes that were decreased by 10 dB on average at frequencies less than 10 kHz with only small effects at higher frequencies. Interruption of the incudo-stapedial joint produced increases and decreases in Hu that were generally less than +/- 10 dB and were frequency dependent. The largest effects on Hu at most frequencies resulted from saline-filling the middle ear, which produced 20 to 30 dB decreases in Hu at frequencies>10 kHz.

3.3 The effect of conductive manipulations on the DPOAE growth function

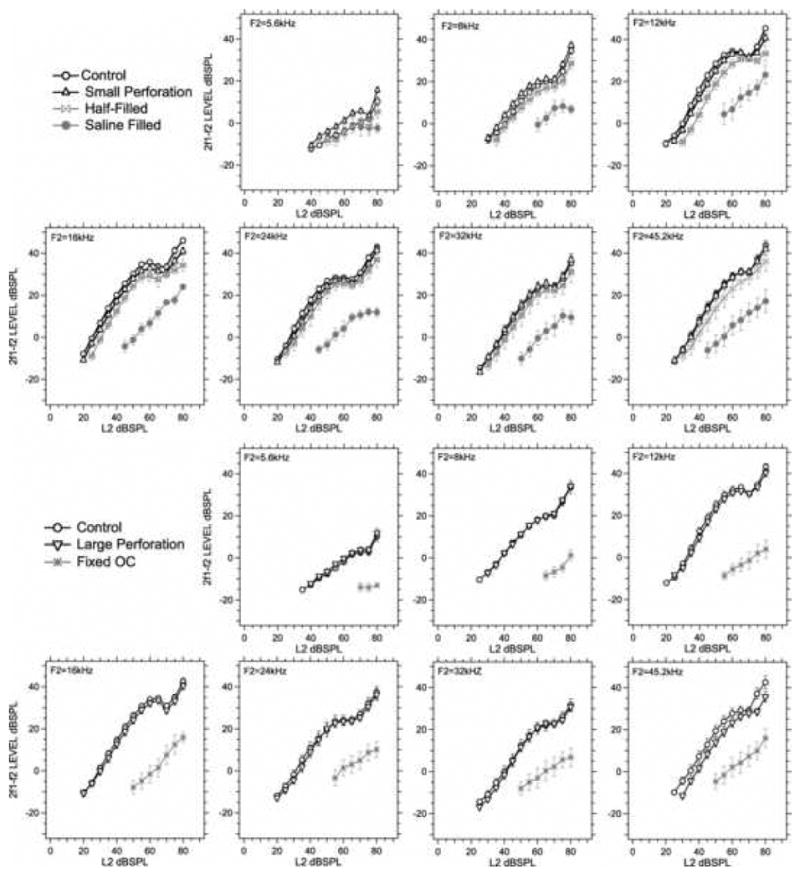

We also compared the effect of our manipulations on the growth of DPOAE with level. Figure 6 displays the mean of all DPOAE growth functions gathered in our different experimental populations for the control case as well as all of the conductive manipulations. The top two rows of this figure show that our small pars flaccida hole and half-saline filling conditions produced small changes in DPOAE growth that were generally consistent with small horizontal shifts of the DPOAE growth functions. Filling the middle ear with saline produced changes in the magnitude, growth rate with level and saturation values of the DPOAEs. The changes in the rate of growth are quantified in Table 2, which demonstrates a similarity in the frequency-dependent growth rate in the control, perforation and half-filled condition, and a significant decreases in growth rate (p < 0.01) at all frequencies after filling the middle ear with saline. The bottom two rows of Figure 6 and the rightmost columns of Table 2 indicate that removal of all of the pars flaccida had little effect on DPOAE growth with level at any frequency, while ossicular fixation produced highly significant (p< 0.001) decreases in DPOAE growth at all frequencies except 8 kHz.

Figure 6.

The averaged DPOAE I/O function (mean ± SEM) for the different middle-ear conditions at each of the seven frequencies. The number of animals included in the means varies from group to group.

Table 2.

The initial growth rate of DPOAE I/O functions computed as the slope of the mean I/O function at each middle-ear condition and stimulus frequency. The initial 5 points that are above the noise were used to determine the slope and the standard error of the slope with least-squares regression analyses.

| Frequency | Slope ± Standard error | Slope (mean ± SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kHz) | Control | Small PF | Half-Filled | Filled | Control | Large PF | OC Fixation |

| 5.6 | 0.42±0.03 | #0.56±0.04 | 0.50±0.06 | †-0.05±0.01 | 0.52±0.02 | #0.59±0.02 | †0.08±0.06 |

| 8 | 0.93±0.06 | #1.08±0.02 | 0.95±0.05 | *0.41±0.14 | 0.88±0.04 | 0.93±0.03 | 0.62±0.13 |

| 12 | 1.32±0.11 | 1.38±0.05 | 1.41±0.05 | †0.66±0.06 | 1.26±0.12 | 1.30±0.09 | †0.51±0.03 |

| 16 | 1.41±0.03 | 1.39±0.03 | 1.38±0.04 | †0.79±0.04 | 1.27±0.05 | 1.17±0.04 | †0.74±0.07 |

| 24 | 1.44±0.04 | #1.31±0.03 | *1.23±0.05 | †0.76±0.06 | 1.17±0.05 | 1.09±0.08 | †0.55±0.06 |

| 32 | 1.18±0.04 | #1.31±0.03 | 1.19±0.02 | *0.80±0.07 | 1.00±0.04 | 1.11±0.07 | †0.52±0.02 |

| 45.2 | 1.34±0.04 | 1.25±0.05 | *1.16±0.05 | †0.75±0.05 | 1.15±0.03 | #1.27±0.03 | †0.60±0.03 |

probability that the slope equals the control slope is less than 5% (p < 0.05)

probability that the slope equals the control slope is less than 1% (p < 0.01)

probability that the slope equals the control slope is less than 0.1% (p< 0.001)

4. Discussion

4.1 The effect of conductive manipulations on DPOAE and ABR threshold

The results summarized in Figures 3 and 4 illustrate that (a) small or large perforations of the mouse pars flaccida do not significantly alter DPOAE and ABR thresholds, (b) a middle ear half-filled with saline produces small increases in DPOAE and ABR thresholds, and (c) a middle ear filled with saline or with fixed ossicles produces significant increases in DPOAE and ABR thresholds.

A similar study in guinea pig (Ueda et al. 1998) demonstrated that small perforations of the pars tensa have little effect on DPOAEs, but that larger perforations (taking up to 50% of the tensa area) reduce DPOAE amplitude by more than 20 dB. The common result between Ueda et al. (1998) and this study that small perforations have little effect on hearing sensitivity, especially at moderate and high frequencies, is consistent with other work (Bigelow et al. 1996; Voss et al. 2001). The different effects of larger perforations may be related to the significant structural and physiological differences in mice and guinea pigs: The guinea pig has a small or non-existent pars flaccida, while in mouse the flaccida is about 1/3 of the total TM area (Kohllöffel 1984). Also, the guinea-pig ear is sensitive to sounds of much lower frequency than the mouse (Fay 1988) and the sound frequencies where Ueda et al. (1998) report the largest perforation-induced losses in DPOAEs are so low that they produce little to no DPOAE or ABR response in mice.

Ueda et al. (1998) also report the results of saline-filling experiments in which half filling the bulla with saline produced only small decreases in DPOAE amplitude, while complete filling reduced the measured DPOAEs to the measurements noise level, which was 20 to 30 dB below the control level. These results are consistent with ours (Figure 3).

4.2 The effect of conductive manipulations on TM Velocity

The TM Velocity data shown in Figure 5 is consistent with other results. Our small and large perforations of pars flaccida produce small decreases in Hu that are only apparent at low-frequencies of stimulation (a decrease of less than 9 dB on average at frequencies less than 3 kHz). Such a small effect has been observed in mice before (Saunders and Summers 1982; Samadi et al. 2005). The relative insensitivity of Hu to ossicular fixations has been reported in humans, where stapes fixations that produce 40 dB or larger conductive hearing losses are associated with 6 dB reductions in Hu magnitude (Huber et al. 2001; Nakajima et al. 2005; Rosowski et al. 2008). The human Hu data are more sensitive to ossicular interruption, which causes a 10 to 15 dB increase in Hu magnitude at low frequencies, but we see smaller changes in mouse. The insensitivity of Hu in the mouse to fixations and interruptions of the ossicular chain is consistent with the expanded anterior process of the mouse malleus and its tight association with the tympanic ring (Rosowski 1992). Such an arrangement could produce a very stiff malleus that dominates ossicular function in mice.

While laser-Doppler vibrometer measurements of Hu combined with audiometric air and bone thresholds have proven useful in deciding the site of lesion in different conductive pathologies (Rosowski et al. 2008), Hu by itself is neither a simple nor reliable indicator of ossicular pathology. However, they appear to be a good estimator of the conductive hearing loss caused by fluid in the middle ear, in that measurements of Hu in human temporal bone and guinea pigs show a progression in the effect of saline filling of the middle-ear air space, much like our results (Ravicz et al. 2004; Gan et al. 2006; Dai and Gan 2008; Dai et al. 2008). Complete filling of the middle-ear cavity produces reductions in Hu magnitude of as large as 30 dB, consistent with the hearing loss observed in patients with middle ears filled with effusion (Ravicz et al. 2004). Partial filling of the cavity produces smaller changes in Hu.

4.3 Comparison of changes in DPOAE, ABR and TM-Velocity caused by our conductive manipulations

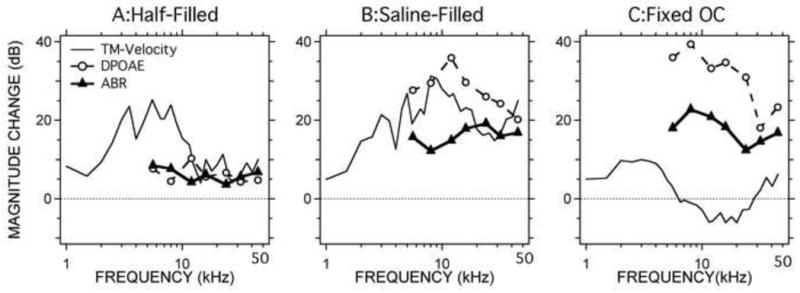

Our measurements of the effects of different conductive pathologies on DPOAE, ABR and Hu are summarized in Figure 7. Figure 7A is a plot of the mean increases in DPOAE and ABR thresholds along with the mean decreases in sound-driven umbo velocity, Hu, that resulted from half-filling the middle ear with saline. Figures 7B and C show the changes in these variables produced by filling the middle ear completely with saline and ossicular fixation to the middle-ear walls with glue. As we saw in Figures 3, 4 and 5, the largest effects on DPOAE and ABR thresholds are produced by fixing the ossicles, while the largest changes in Hu are observed in the saline-filled middle ears.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of changes in DPOAE threshold, ABR threshold and the inverse of TM-Velocity (1/Hu) caused by the middle-ear manipulations. 7A shows the changes caused by half-filling of saline. 7B compares the shifts caused by complete filling of saline. 7C illustrates the changes caused by ossicular chain fixation.

The changes produced by the three types of manipulation are similar in some ways, but different in others. One of the most obvious differences between the three measurement variables is that we report umbo velocity measurements at frequencies as low as 1 kHz, while ABR and DPOAE are reported at frequencies above 4 kHz. In the frequency range of overlap between the three measurements four features are readily visible: (1) In the middle ear half-filled with saline condition, at frequencies above 10 kHz, the mean changes in ABR, DPOAE and TM-sensitivity (as characterized by Hu) are small (<10 dB); at lower frequencies the changes in TM-sensitivity are larger. (2) Total filling with saline produces a large (15 to 35 dB) and significant reduction in the sensitivity of ABR, DPOAE and TM-sensitivity between 4 and 50 kHz. The decrease in DPOAE and TM sensitivity is largest near 10 kHz and falls slightly as frequency increases, but the change in ABR sensitivity is roughly flat with frequency. (3) Ossicular fixation produces a significant decrease in ABR and DPOAE sensitivity (an increase in threshold) of 15 to 40 dB with only small changes in TM-sensitivity. (4) At any frequency and condition where there is a significant increase in ABR thresholds, the increase in DPOAE thresholds is larger.

If we make the reasonable assumption that our manipulations only produce conductive hearing losses, then we can use the changes in ABR threshold as a measure of the conductive hearing loss. In the scheme of Figure 1, we quantify the alteration in ‘inward’ middle-ear transmission in terms of the change in ABR thresholds. With that assumption in place, Figure 7 then suggests that (a) the changes we measure in DPOAE threshold after our manipulations are significantly larger than the loss in ‘inward’ sound transmission through the ear, and (b) the measured change in TM-sensitivity either exaggerates or underestimates the real conductive hearing loss. Statement a. is consistent with the model of Figure 1, in that any difference between the conductive hearing loss affecting inward sound transfer and the change in DPOAE thresholds can be explained by a ‘conductive’ alteration in outward sound transfer. Statement b. is consistent with other observations that LDV measurements of umbo velocity are not accurate estimators of conductive hearing loss.

4.4 Quantification of the difference in the effect of conductive pathologies on DPOAE and ABR

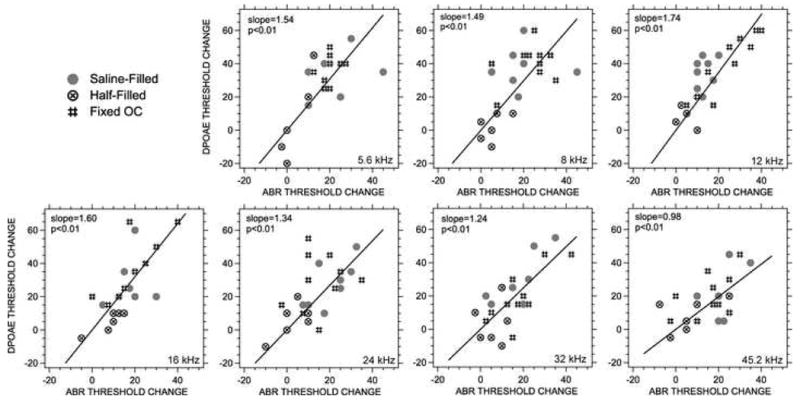

While comparisons of the data in Figure 7 demonstrate that induced conductive pathology has a larger effect on DPOAE thresholds than ABR thresholds, which is consistent with the pathology affecting both the inward and outward transfer of sound energy through the middle ear, we now try to quantify the relative effect of the conductive pathologies on the inward and outward transfer of sound through the middle ear. The first step in this process is to relate the changes in ABR and DPOAE thresholds. Figure 8 shows plots of the manipulation-induced changes in DPOAE threshold vs the changes in ABR thresholds for each manipulation in each ear at each of the seven frequencies. The top-left panel shows all of the data at 5.6 kHz, where each point represents the paired change in DPOAE and ABR thresholds produced by one manipulation in one ear. We only plot the results of the three manipulations that produced significant alterations in thresholds, including half- and full-saline filling, and ossicular fixation. Individual data are only included if each of the post-manipulation thresholds were measurable. The other six panels show the changes at the six other measurement frequencies. Included in each panel is a line described by least-squares linear regression calculation assuming an intercept of 0. (The assumption of 0 intercept is consistent with the expectation that a conductive manipulation that does not affect ABR threshold has no effect on DPOAE threshold.) The slopes that relate the dB change in DPOAE thresholds to the dB change in ABR thresholds vary between 1.74 and 0.98 with the largest slopes in the lower frequencies, and all of these slopes are statistically different from 0.

Figure 8.

The relationship between DPOAE and ABR threshold shifts (A regression analysis). The points represent paired measurements of the change in ABR and DPOAE threshold produced by either half-filling with saline, full-filling with saline or ossicular chain fixation in the different ears. The regression lines were computed using least-squares techniques assuming the intercept of the line is 0. The probability that the slope is 0 is included in each panel; all of the lines explain a significant part of the variation in the data.

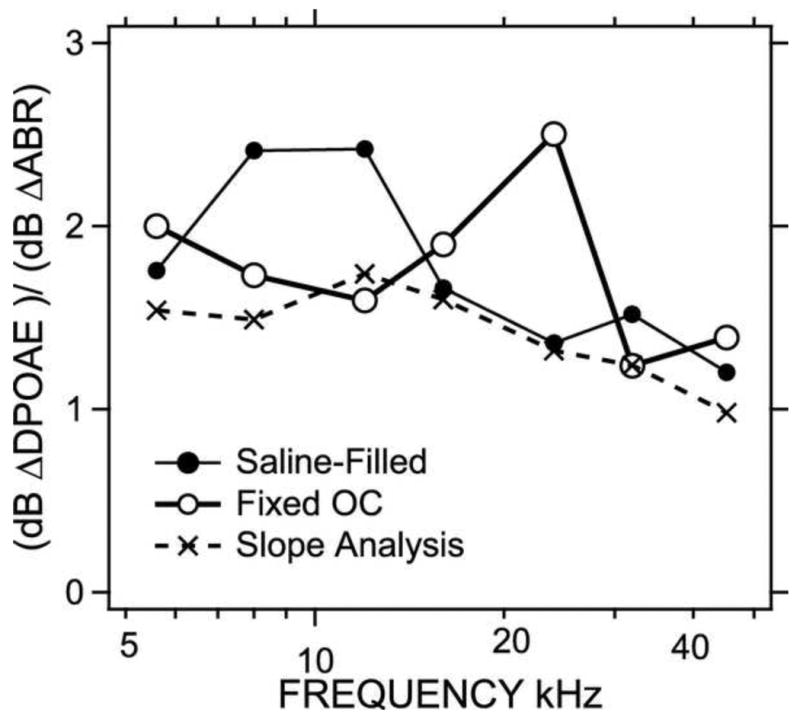

The slopes of the seven functions in Figure 8 are plotted vs. frequency in Figure 9 (the dashed line). The suggestion from the slope analysis is that the additional conductive loss imposed on the outward transfer of DPOAE sound is greater at low frequencies and decreases as frequency increases until the additional loss disappears at 44 kHz. (At 44 kHz, the dB change in DPOAE threshold equals the change in ABR threshold.) We can compute the same relative change from the mean data of Figure 7, by computing the ratio between the mean dB changes in DPOAE and ABR thresholds. The thin line with filled circles of Figure 9 shows the ratio of the mean threshold changes from the saline-filled condition, while the thicker line with open circles shows the ratio of the threshold changes produced by ossicular fixation. The two sets of ratio values are somewhat larger than the computed slopes, though they share the common feature of being near 1 at the highest frequencies and closer to 2 at the lower frequencies.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the slopes computed by the regression analyses of Figure 8 and the ratio of the dB threshold shifts of DPOAE and ABR measurements.

If we again assume that the changes we see in ABR quantify the conductive hearing loss produced in the inward flow of sound into the middle ear, this ratio and slope analysis quantifies the independent effect of the conductive pathology on the outward flow of sound from the inner ear to the external ear. Specifically, Figure 9 quantifies Y, the change in DPOAE threshold (quantified in dB) relative to the change in ABR threshold, where:

| (1) |

If we equate ΔdBABR and ΔdBinward, then

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

where (Y-1) describes the frequency-dependent proportionality factor relating the multiplicative change in outward and inward transmission. This analysis suggests that at points where the calculations plotted in Figure 9 are near 2, Y = 2 and the induced conductive change in outward and inward sound transfer are about equal (ΔdBoutward ≅ ΔdBinward). At the other extreme, at the highest frequencies in Figure 9, where Y approximates 1, then the change in DPOAE can be mostly explained by the conductive change in inward sound with little change in outward sound travel (ΔdBoutward ≅ 0).

4.5 Conductive alterations in the growth of the DPOAE I/O function

Some authors have proposed that conductive alterations in linear sound processing by the middle ear should produce parallel shifts in DPOAE growth functions (Gehr et al. 2004; Janssen et al. 2004). In terms of Figure 1, the suggestion is that conductive pathology only affects the gain of the inward and outward sound transfer and has no effect on the generation of DPOAEs within the inner ear. Such a change in linear gain should produce simple horizontal shifts in the growth of DPOAEs. The alterations we observe in the growth rate and in the saturation values in DPOAE growth functions (Figure 6, Table 2) with 15 to 35 dB conductive losses are not consistent with simple parallel shifts in DPOAE growth. This inconsistency suggests a more complicated relationship between DPOAE growth and conductive hearing loss: One possibility is that the altered middle-ear load has an effect on the distortion generation process, but while many models of OAE generation (e.g. Shera et al. 2005) suggest that alterations in middle-ear load may affect the frequency dependence of distortion generation, a change in growth rate of distortion with stimulus levels is unexpected. A second possible explanation is that our techniques, where the large conductive loss is only introduced after two or three smaller changes, produce some sensorineural loss that is responsible for the change in slopes and the saturation values in the DPOAE values.

However, the small shift-like changes in growth we see after the more minor conductive manipulations suggest that our measurement techniques are not introducing sensory changes in DPOAE production. A third possibility is that the large conductive losses introduced by our manipulations reduces the DPOAE levels generated by the primary inner-ear distortion source to such low levels that secondary DPOAE sources, e.g. middle-ear or other mechanical nonlinearities within the ear or stimulus generation system, which may not depend on backward sound transmission (Rosowski et al. 1984), now dominate the measured DPOAEs.

Another method for using DPOAE growth to evaluate normal and pathologic auditory thresholds has been proposed by Boege and Janssen (2002) who measured the growth of DPOAEs in ear-canal sound pressure and expanded on by others (Dalhoff et al. 1007; Turcanu et al. 2007, 2009) who measure the growth of DPOAEs reflected in distortions within the umbo-velocity response to two-tone stimuli. This method is not directly based on any simple linear model of the middle ear, but instead uses a nonlinear transformation of measured distortion and stimulus levels to predict auditory thresholds in human patients and experimental animals. The results of this procedure look encouraging, but no mechanistic explanation for why it works has been put forward.

4.6 Separation of conductive and sensorineural hearing losses

The identification of the conductive components of hearing loss is generally easy in human adults and adolescents, where the air-bone gap computed from the combination of air-conduction and bone-conduction audiometry is the gold standard method of quantifying a conductive hearing loss. In non-human animals, however, where no bone-conduction standards exist, the separation of conductive and inner-ear pathologies is more problematic. This separation of conductive and sensori-neural pathology is of special interest when trying to determine the hearing phenotype in the never ending series of mouse genotypes that are available for study. A specific example is the osteoprotegrin knockout mouse (OPG-/-) used as model of human otosclerosis (Kanzaki et al. 2006; Zehnder et al. 2006). Adult, moderately aged OPG-/- mice show clear ossicular abnormalities that have been used to explain observations of increased auditory thresholds to sound (Kanzaki et al. 2006). Indeed, older OPG-/- mice show DPOAE threshold increases (in dB) that are about a factor of two greater than the dB increases in ABR thresholds when compared with similarly aged-control mice (Zehnder et al. 2006), just as our study suggests for a conductive hearing loss. However, in younger OPG-/- mice, the shifts in ABR and DPOAE thresholds are more equal (Zehnder et al. 2006), which is more consistent with sensory hearing loss. The suggestion, from our analysis in the present paper, is that the OPG-/- mouse exhibits a mixed hearing loss that progresses with age, with a large conductive hearing loss prominent in older mice. It would seem then, that comparisons of changes in DPOAE and ABR thresholds may be useful for determining the site of lesion while screening hearing in mice of different genotypes.

5. Conclusions

Perforation of the mouse pars flaccida has no significant effect on ABR and DPOAE thresholds, but a large pars flaccida hole has a small but significant effect on TM velocity (HU) magnitude at frequencies < 3 kHz.

A middle ear half-filled with saline produces small increases in ABR and DPOAE thresholds and similar-sized decreases in TM velocity.

A middle ear full of saline produces significant increases in ABR and DPOAE thresholds and similar sized decreases in TM velocity.

Ossicular fixations produce large increases in ABR and DPOAE but only small changes in TM velocity.

While measurements of TM velocity after filling the middle-ear with fluid showed changes in TM sensitivity that are comparable to the changes in DPOAE and ABR thresholds, ossicular manipulations produce widely different changes in umbo velocity and ABR and DPOAE thresholds.

Conductive pathology produces a DPOAE threshold change in dB that is 1.5 to 2.5 times larger than the ABR threshold change at frequencies less than 30 kHz and nearly equal at the highest frequencies.

Our data do not generally support the idea that manipulations of the middle ear produce simple shifts in DPOAE I/O functions.

Observations of larger increases in DPOAE vs ABR thresholds may indicate the contribution of middle-ear conductive pathology to the hearing loss.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH, and China Scholarship Council for financial support, as well as the Kujawa laboratory and the staffs of the Eaton-Peabody Lab and Department of Otolaryngology for aid in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen JB. Measurements of eardrum acoustic impedance. In: Allen J, Hall J, Hubbard A, Neely S, Tubis A, editors. Peripheral Auditory Mechanisms. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1986. pp. 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JB, Jeng PS, Levitt H. Evaluation of human middle ear function via an acoustic power assessment. JRRD. 2005;42:63–78. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.04.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avan P, Büki B, Maat B, Dordain M, Wit HP. Middle ear influence on otoacoustic emissions. I: Noninvasive investigation of the human transmission apparatus and comparison with model results. Hearing Research. 2000;140:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békésy von G. Experiments in Hearing. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow DC, Swanson PB, Saunders JC. The effect of tympanic membrane perforation size on umbo velocity in the rat. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:71–76. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199601000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boege P, Janssen T. Pure-tone threshold estimation from extrapolated otoacoustic emissions in normal and cochlear hearing loss ears. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;111:1810–18. doi: 10.1121/1.1460923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Gan RZ. Change of middle ear transfer function in otitis media with effusion model of guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2008;243:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai C, Wood MW, Gan RZ. Combined effect of fluid and pressure on middle ear function. Hear Res. 2008;236:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalhoff E, Turcanu D, Zenner HP, Gummer AW. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions measured as vibration on the eardrum of human subjects. PNAS. 2007;104:1546–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610185103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan DE, Cohen YE, Saunders JC. Middle-ear development: IV. Umbo motion in neonatal mice. J Comp Physiol A. 1994;174:103–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00192011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay RR. Hearing in Vertebrates: a Psychophysics Databook. Hill-Fay Associates; Winnetka, Illinois: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney MP, Grant IL, Marryott LP. Wideband energy reflectance in adults with middle-ear disorders. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2003;46:901–911. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/070). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan RZ, Dai C, Wood MW. Laser interferometry measurements of middle ear fluid and pressure effects on sound transmission. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;120:3799–3810. doi: 10.1121/1.2372454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehr DD, Janssen T, Michaelis CE, Deingruber K, Lamm K. Middle ear and cochlear disorders result in different DPOAE growth behaviour: Implications for the differentiation of sound conductive and cochlear hearing loss. Hear Res. 2004;193:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber AM, Schwab C, Linder T, Stoeckli SJ, Ferrazzinin M, Dillier N, Fisch U. Evaluation of eardrum laser doppler interferometry as a diagnostic tool. The Laryngoscope. 2001;111:501–507. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen T, Gehr DD, Klein A, Müller J. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions for hearing threshold estimation and differentiation between middle-ear and cochlear disorders in neonates. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117:2969–79. doi: 10.1121/1.1853101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki S, Ito M, Takada Y, Ogawa K, Matsuo K. Resorption of auditory ossicles and hearing loss in mice lacking osteoprotegerin. Bone. 2006;39:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohllöffel LUE. Notes on the comparative mechanics of hearing. III. On Shrapnell's membrane. Hearing Research. 1984;13:83–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Long-term sound conditioning enhances cochlear sensitivity. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:863–73. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.2.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maison SF, Rosahl TW, Homanics GE, Liberman MC. Functional role of GABAergic innervation of the cochlea: phenotypic analysis of mice lacking GABA(A) receptor subunits alpha 1, alpha 2, alpha 5, alpha 6, beta 2, beta 3, or delta. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10315–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2395-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peake WT, Rosowski JJ, Lynch TJ., III Middle-ear transmission: Acoustic vs. ossicular coupling in cat and human Hear Res. 1992;57:245–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90155-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker OT. Otological correlates of audiology. In: Katz J, editor. Handbook of Clinical Audiology. Williams and Wilkins; BAltimore: 1972. pp. 36–59. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis RH, Shanks JE. Tympanometry. In: Katz J, editor. Handbook of clinical audiology. Williams & Wilkens; BAltimore: 1985. pp. 438–475. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant SN, Rosowski JJ. Auditory physiology (middle-ear mechanics) In: Gulya A, Glasscock MI, editors. Surgery of the Ear, 5 ed. B.C. Decker. Hamilton Ontario; 2003. pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Møller AR. Experimental study of the acoustic impedance of the middle ear and its transmission properties. Acta oto-Laryngol. 1965;60:129–149. doi: 10.3109/00016486509126996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima HH, Ravicz ME, Rosowski JJ, Peake WT, Merchant SN. Experimental and clinical studies of malleus fixation. The Laryngoscope. 2005;115:147–154. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000150692.23506.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham K, Sun XM, Kim DO. Noninvasive assessment of auditory function in mice: Auditory brainstem response and distortion product otoacoustic emissions. In: Willott J, editor. Handbook of mouse auditory research: From behavior to molecular biology. CCR Press LLC; Boca Raton, FL: 2001. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ravicz ME, Rosowski JJ, Merchant SN. Mechanisms of hearing loss resulting from middle-ear fluid. Hear Res. 2004;195:105–30. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ. Hearing in transitional mammals: Predictions from the middle-ear anatomy and hearing capabilities of extant mammals. In: Webster DB A.N.P.a.R.R.F., editor. The Evolutionary Biology of Hearing. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1992. pp. 615–631. [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ. Outer and middle ear. In: Popper A, Fay R, editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research: Comparative Hearing: Mammals. IV. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1994. pp. 172–247. [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Brinsko KM, Tempel BL, Kujawa SG. The ageing of the middle ear in 129S6/SvEvTac and CBA/CaJ mice: Measurements of umbo velocity, hearing function and the incidence of pathology. JARO. 2003;4:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Nakajima HH, Merchant SN. Clinical utility of laser-Doppler vibrometer measurements in live normal and pathologic human ears. Ear & Hearing. 2008;29:3–19. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31815d63a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski JJ, Peake WT, White JR. Cochlear nonlinearities inferred from two-tone distortion products in the ear canal of the alligator lizard. Hear Res. 1984;13:141–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadi DS, Saunders JC, Crenshaw EBC., III Mutation of the POU-domain gene Brn4/Pou3f4 affects middle-ear sound conduction in the mouse. Hear Res. 2005;199:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JC, Summers RM. Auditory structure and function in the mouse middle ear: An evaluation by SEM and capacitive probe. J Comp Physiol, A. 1982;146:517–525. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA, Tubis A, Talmadge CL. Coherent reflection in a two-dimensional cochlea: Short-wave versus long-wave scattering in the generation of reflection-source otoacoustic emissions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:287–313. doi: 10.1121/1.1895025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel KP, Moorjani P, Bock GR. Mixed conductive and sensorineural hearing loss in LP/J mice. Hear Res. 1987;28:227–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonndorf J, Duvall AJ. Loading of the tympanic membrane: its effect upon bone conduction in experimental animals. Acta Oto-Lar, Suppl. 1966:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tonndorf J, Tabor JR. Closure of the cochlear windows: Its effects upon air and bone-conduction. Ann Otol Rhinol Lar. 1962;71:5–29. doi: 10.1177/000348946207100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcanu D, Dalhoff E, Zenner HP, Gummer AW. Laser-Doppler-vibrometrische Messungen von DPOAE and Menschen. Trommelfellschwingungen spiegeln Mittel- und Innenohrcharactkteristika wider. HNO. 2007;55:930–7. doi: 10.1007/s00106-007-1582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcanu D, Dalhoff E, Müller M, Zenner HP, Gummer AW. Accuracy of velocity distortion product otoacoustic emissions for estimating mechanically based hearing loss. Hear Res. 2009;251:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H, Nakata S, Hoshino M. Effects of effusion in the middle ear and perforation of the tympanic membrane on otoacoustic emissions in guinea pigs. Hear Res. 1998;122:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss SE, Rosowski JJ, Merchant SN, Peake WT. How do tympanic-membrane perforations affect human middle-ear sound transmission? Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:169–173. doi: 10.1080/000164801300043343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Hequembourg SJ, Atencio CA, Rosowski JJ, Liberman MC. Acoustic injury in mice: 129/SvEv is exceptionally resistant to noise-induced hearing loss. Hearing Research. 2000;141:97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehnder AF, Kristiansen AG, Adams JC, Kujawa SG, Merchant SN, McKenna MJ. Osteoprotegrin knockout mice demonstrate abnormal remodeling of the otic capsule and progressive hearing loss. The Laryngoscope. 2006;116:201–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000191466.09210.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwislocki J. Analysis of the middle-ear function. Part I: Input impedance. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1962;34:1514–1523. [Google Scholar]