Abstract

Objective:

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) among boys has been associated with a variety of subsequent maladaptive behaviors. This study explored a potential connection between CSA and an increased likelihood of risky sexual behavior in adulthood. Further, the study examined whether or not alcohol use may contribute to this relationship.

Method:

As part of a study on alcohol and sexual decision-making, 280 heterosexual men completed multiple background questionnaires pertaining to past and current sexual experiences and patterns of alcohol use. CSA history was obtained and severity ratings were made based on type of contact reported.

Results:

CSA was reported by 56 men (20%). Structural equation modeling revealed that CSA positively predicted number of sexual partners directly as well as indirectly, through its effect on alcohol use. Specifically, greater CSA severity predicted significantly lower age of first intoxication, which in turn predicted greater current alcohol consumption, followed by greater use of alcohol before sexual intercourse, leading to an increased number of reported sexual partners. The reported frequency of condom use was not predicted by CSA severity or the alcohol use pathway.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that CSA influences risky sexual behavior via multiple pathways and that more severe CSA may lead to elevated sexual risk indices. Moreover, these results suggest that men may elevate their risk of sexually transmitted infections via high numbers of sexual partners versus irregular condom use.

Practical implications:

These results highlight the need for adequate assessment and early interventions in order to mitigate the effects CSA may have on subsequent alcohol use and risky sexual behavior. Secondly, ensuring that male CSA victims understand the inherent risks of high numbers of sexual partners may be an effective strategy to interrupt the path toward risk-taking.

Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) among males is not uncommon. Until recently, accurate prevalence rates have remained elusive---apparently because rates of abuse among boys have been masked by particularly low rates of abuse disclosure. Current estimates are that roughly 14% of males are sexually abused during childhood (Briere & Elliot, 2003). Unfortunately, this percentage may also be an underestimate due to continued low rates of disclosure.

While less robust than the research literature using female samples, there is ample evidence that male CSA is associated with a broad spectrum of detrimental sequelae (Holmes & Slap, 1998; Romano & De Luca, 2001). Increased alcohol consumption and elevated rates of sexual risk-taking have both been observed among various populations of male survivors of CSA (DiIorio, Hartwell, & Hansen, 2002; Paul, Catania, Pollack, & Stall, 2001; Hamburger, Leeb, & Swahn, 2008). Additionally, increased alcohol consumption has independently and convincingly been associated with increased risky sexual decision-making (Cooper, 2002; George & Stoner, 2000).

These two lines of independent but intersecting research findings---that CSA is associated with alcohol use and sexual risk-taking and that alcohol use is related to sexual risk-taking---suggest that alcohol is an important component in the path between CSA and subsequent sexual risk-taking. Using survey methodology, the current study investigated these possible linkages among CSA, alcohol use, and sexual risk-taking in a sample of adult heterosexual men from the community.

Childhood sexual abuse and risky sexual practices

Multiple studies indicate a positive association between CSA and risky sexual practices (e.g., elevated number of sexual partners and unprotected intercourse) among adolescent and adult males (for a review, please see Purcell, Malow, Dolezal, & Carballo-Dieguez, 2004). CSA experiences seem to influence sexual risk-taking in an early and ongoing fashion. Studies have associated CSA with early consensual sexual initiation (Wilsnack, Vogeltanz, Klassen, & Harris, 1997) with one study reporting that male CSA survivors were younger at onset of sexual intercourse than female CSA survivors (Chandy, Blum, & Resnick, 1996). Among adolescent male survivors of CSA, elevated rates have been observed for number of sexual partners (Saewyc, Magee, & Pettingell, 2004) and inconsistent condom use (Brown, Lourie, Zlotnick, & Cohn, 2000). Among adult survivors, in addition to a greater number of sexual partners and inconsistent condom use (Bartholow et al., 1994; DiIorio et al., 2002; Holmes & Slap, 1998), CSA has also been associated with exchanging sex for drugs or money (e.g., Van Dorn et al., 2005), and using alcohol prior to or during sex (e.g., Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2006). Among both adolescent and adult male survivors, elevated rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been observed (Holmes & Slap; Futterman, Hein, Reuben, Dell, & Shaffer, 1993; Paul et al., 2001).

Published findings linking male CSA with sexual risk-taking have largely been based on samples drawn from populations with high STI risk indices (e.g., men who have sex with men [MSM], homeless populations, STI clinic patients). As such, it is not clear if these results generalize across all male survivors of CSA. The present study addressed this gap by investigating these relationships in community sample of heterosexual men.

Childhood sexual abuse and alcohol use

To date, Purcell and colleagues (2004) have suggested the only conceptual model, tailored specifically for males, to explain the link between CSA and subsequent risky sexual behavior. The model they proposed suggests that CSA exerts influence on the distal outcome (HIV risk behavior) indirectly through its effect on more proximal outcomes that may serve as mediating variables. One of the proposed paths to risk-taking is through the use of substances, including alcohol. Alcohol use is a particularly important path to investigate given that some studies suggest that alcohol use among survivors of CSA may be of particular concern among males (e.g., Garnefski & Arends, 1998).

CSA in boys has been linked to increased and maladaptive alcohol use (Dube et al., 2005; Hamburger, Leeb, & Swahn, 2008; Nagy, Adcock, & Nagy, 1994; Garnefski & Arends, 1998; DiIorio et al., 2002; Senn et al., 2006; Wolfe, Francis, & Straatman, 2006). CSA may affect a person's drinking behavior beginning early in life. In a study of abused and non-abused boys aged 12 to 19, Garnefski and Arends noted that abused boys reported drinking nearly three times the amount of alcohol consumed by their non-abused counterparts. More recently, in an epidemiological study of survivors of childhood maltreatment, Hamburger et al. found that among male middle school and high school students, CSA was positively associated with preteen alcohol use. Further, the authors also reported that, when compared to those without a history of sexual abuse, these male survivors of CSA were 2.5 times more likely to report binge drinking (defined as consuming five or more drinks in a row).

While both male and female victims of CSA have shown elevated drinking levels, maladaptive adolescent drinking among CSA survivors may pose a unique risk for males. In 1996 a group of researchers reported that while female survivors of CSA reported consuming alcohol more frequently than males CSA survivors, the males were more likely than sexually abused females to consume five or more drinks during one episode and to drink before or during school (Chandy et al., 1996). Similarly, Garnefski and Arends (1998) reported a gender interaction such that both male and female survivors of CSA drank more than those without a history of CSA, but that the difference between the groups was significantly larger among males.

In addition to early drinking initiation and binge drinking early in life, CSA has been linked to increased alcohol consumption and related problems for men in mid-life as well. DiIorio and colleagues, in a study of men ranging in age from 18 to 70 (mean age was 32), reported that men who experienced unwanted sexual activity during childhood were significantly more likely to report alcohol-related problems than men without histories of CSA (DiIorio et al., 2002). Using a population drawn from a managed care system in Southern California, a study of almost 8,000 men (mean age was 56) reported that men with a history of CSA had increased odds of reporting problems with alcohol. Further, the authors reported that victims of abuse that included intercourse were at increased odds for reporting problems with alcohol compared to men whose abuse experiences were limited to non-intercourse activities (Dube et al., 2005). This is in line with prior research that has linked increased severity of abuse with worsened outcomes (for a review, see Romano & De Luca, 2001). In sum, studies have consistently indicated that a history of CSA in boyhood is associated with elevated, maladaptive, and enduring patterns of drinking behavior.

Alcohol use and risky sexual practices

Research has demonstrated a relationship between alcohol consumption and an array of risky sexual practices. This positive association has been demonstrated in research using both survey and experimental methods (for a review, see Cooper, 2002). Since Cooper's review, research has continued to support the alcohol-risky sex link. For instance, a recent study reported that heavy alcohol use was significantly associated with having multiple sex partners in the prior 12 months and was the single biggest risk factor for having experienced an unprotected sexual encounter while intoxicated (Kim, De La Rosa, Trepka, & Kelley, 2007). Fully 30.8% of those that reported heavy drinking also reported unprotected intercourse under the influence of alcohol. This compares to just 7.5% of participants that did not report heavy alcohol use, and suggests that the volume of alcohol consumption (versus drinking in general) may be an important alcohol-use dimension to incorporate conceptually. However, Kim and colleagues did not find that alcohol use was related to condom use behavior overall. This latter finding is in line with much of the event-level research (in which specific events are probed), which suggests added complexity in the association between alcohol consumption and overall condom use (Cooper, 2006). However, extending the finding of Kim et al.'s global association study, a 2007 event-level study of the relationship between alcohol consumption and unsafe sex among first-year college students reported significantly increased odds of having unsafe sex on days on which participants drank more than their average daily consumption (Neal & Fromme, 2007). Another recent event-level analysis found that while the link between alcohol use and condom use was only a trend, alcohol use was significantly related to a decrease in discussing “topics pertinent to safe sexual practices” (Goldstein, Barnett, Pedlow, & Murphy, 2007).

Well-designed laboratory experiments have corroborated event-level survey research indicating that alcohol intoxication fosters risky sexual decision-making (see review, Hendershot & George, 2007). For example, in multiple studies, alcohol's pharmacological effect has been shown to impair a person's ability to simultaneously attend to opposing cues (Steele & Josephs, 1990). Instead, alcohol seems to render a person disproportionately affected by the cues that are most salient. In the sexual domain, when instigatory cues such as sexual arousal and desire are more salient than inhibitory cues (e.g., not knowing a potential partner's sexual history), alcohol intoxication can increase a person's intention to take sexual risks (Davis, Hendershot, George, Norris, & Heiman, 2007; George et al., 2009; Stoner, et al., 2008). Acute alcohol intoxication has also been experimentally shown to interfere with a person's ability to effectively negotiate condom usage (Maisto, Carey, Carey, & Gordon, 2002; Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, & Schum, 2004). In sum, alcohol's association with sexual risk-taking, while not a simple relationship, is supported by substantial and diverse research findings.

CSA – Alcohol Use – Risky Sex Nexus: Prior Research

To date, only one published study has examined the role of alcohol as a potential mediator in the relationship between CSA and later sexual risk-taking among males. Using a high-risk sample drawn from an STI clinic, Senn and colleagues (2006) reported that, among men, alcohol use during intercourse mediated the relationship between CSA and number of sexual partners in the past three months. CSA was associated with number of episodes of unprotected sex, but this relationship was not mediated by alcohol use during intercourse. Additionally, alcohol use did not mediate CSA's effects on risk-taking behaviors among women in the sample. The finding that gender moderated the mediated relationship again suggests that perhaps alcohol use is an especially meaningful component in this relationship for men (versus women) and highlights the need for more research in this domain using a variety of samples. In line with most of the published research on CSA, Senn and colleagues defined CSA history dichotomously (present v. absent). However, because abuse severity has been associated with worse outcomes, taking severity of abuse into account may allow for a more thorough understanding of these relationships. The present study incorporated abuse severity in the categorization of abused participants.

The present study

The present study aimed to extend previous work by examining the relationships among CSA, alcohol use, and risky sexual decision-making among males by sampling an understudied population. Instead of consisting of homeless men, MSM, or men recruited from a clinical setting, our sample was comprised of heterosexual men recruited from the general community. This population of men have risk indices that are presumably lower than the aforementioned populations, but are an important demographic to understand; a fact that is underscored by the increasing rate of sexually-contracted HIV infections among heterosexual women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Additionally, rather than dichotomize CSA, the present study defined CSA on a continuum of severity.

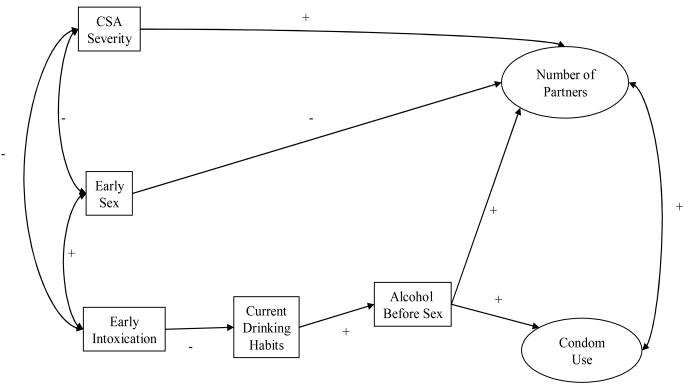

The present study addressed three hypotheses. First, it was hypothesized that severity of CSA would be directly associated with increases in risky sexual practices. Second, it was hypothesized that severity of abuse experience would be positively associated with alcohol use. Furthermore, we predicted that CSA severity would be associated with earlier use of alcohol and that alcohol use would endure over time. Last, it was hypothesized that severity of CSA would influence risky sexual behavior indirectly via an alcohol use pathway. The hypothesized model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Method

Participants

Single heterosexual men (n = 280) were recruited from the greater Seattle area via ads in local weekly newspapers, the University of Washington student newspaper, and flyers posted at the university and nearby community colleges and other social environments. Ads and flyers stated that the study was about “social drinking and decision-making.” Inclusion requirements consisted of being (a) between the ages of 21 and 35, (b) interested in dating an opposite sex partner, (c) not currently in a steady, committed dating relationship, and (d) a moderate drinker. Exclusion criteria consisted of (a) current problem drinking, (b) a history of problem drinking, and (c) having a current health condition or medication for which alcohol is contraindicated. Alcohol-related requirements for study participation were due to the alcohol-administration protocol employed in the larger experimental procedure.

Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Demographic information for the full sample is provided in the first column. The second and third columns, respectively, provide demographic information for those with histories with and without CSA. As indicated in the Table, the CSA sample included a significantly higher proportion of African-Americans, a lower proportion of current students, and a lower proportion of those with an annual salary of $61,000 or more

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 280)

| Variable | Full sample | CSA+ sample | CSA− sample |

Significant difference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.4 (3.9) | 26.2 (3.5) | 25.1 (4.0) | ||||

| Drinking Level (number of drinks per week) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (9.3) | 14.6 (8.4) | 16.5 (9.5) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Race/ethnicity a | |||||||

| African-American | 15 | 5.4 | 7 | 12.5 | 8 | 3.6 | ** |

| Latino | 9 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.8 | 8 | 3.6 | |

| European-American | 203 | 72.5 | 36 | 64.3 | 167 | 74.6 | |

| Asian-American | 7 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 3.1 | |

| Native Hawaiian- Pacific Islander |

5 | 1.8 | 2 | 3.6 | 3 | 1.3 | |

| Native North American | 5 | 1.8 | 2 | 3.6 | 3 | 1.3 | |

| Multi-racial/Other | 29 | 10.4 | 6 | 10.7 | 23 | 10.3 | |

| Student Status a | |||||||

| Yes | 105 | 38.5 | 14 | 25.0 | 91 | 40.6 | * |

| Annual Income (household) a | |||||||

| ≤ $10,999 | 63 | 22.5 | 16 | 28.6 | 47 | 21.0 | |

| $11,000 - $20,999 | 70 | 25.0 | 19 | 33.9 | 51 | 22.8 | |

| $21,000 - $30,999 | 53 | 18.9 | 10 | 17.9 | 43 | 19.2 | |

| $31,000 - $40,999 | 16 | 5.7 | 2 | 3.6 | 14 | 6.3 | |

| $41,000 - $50,999 | 12 | 4.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 11 | 4.9 | |

| $51,000 - $60,999 | 5 | 1.8 | 1 | 1.8 | 4 | 1.8 | |

| ≥ $61,000 | 47 | 16.8 | 4 | 7.1 | 43 | 19.2 | * |

Sums may not equal 280 because some participants selected “No Answer”.

p < .05

p < .01

Procedure

Callers interested in participating in the study were screened via telephone and eligible callers were immediately scheduled for a laboratory visit. Once participants arrived at our lab, informed consent was obtained and the participant was escorted to a private office. At this point the participant was left alone to complete a series of background questionnaires as part of a larger experimental study; these background measures are the focus of the current analysis. Prior to being discharged, all participants were debriefed, compensated for their time, and issued resource materials regarding STIs. All procedures and materials were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Washington.

Measures

Childhood sexual abuse and abuse severity coding

To assess CSA, we used a modified version of a frequently used measure originally created by David Finkelhor (1979). This questionnaire defines CSA as sexual activities at or before age 14 with a person 5 or more years older. This measure assesses various types of sexual experiences including exhibition, fondling, oral sex, and penetrative sex. For the current study, participants' CSA status was coded based on their most severe type of physical contact experienced. Specifically, participants that reported no CSA or exhibition only were coded as “0”; participants that reported fondling (but not oral sex or intercourse) were coded as “1”; those that reported oral sex (but not penetrative intercourse) were coded as “2”, and participants that reported penetrative intercourse were coded as “3”. Gauging severity by type of sexual contact is consistent with prior research (Hulme, 2007).

Self-reported HIV/STI risk behaviors

During the questionnaire session, participants were asked to report the age at which they first had consensual intercourse, numbers of sexual partners, and their patterns of condom use in a variety of situations. Specifically, participants were asked to report (a) their number of lifetime sexual partners, (b) their number of sexual partners in the past year, and (c) the number of one-time sexual partners in their lifetime (i.e., “one-night stands”). Regarding condom use, participants were asked how often in the last 12 months they had sex without a condom (a) overall, (b) on a first date, and (c) when a condom was not available. Response options for the condom items ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (about half the time) to 6 (all of the time).

Self-reported alcohol use behaviors

To assess participants' alcohol use, we probed alcohol use early in life, typical drinking amount, and the use of alcohol prior to or during intercourse. In order to gauge the age of drinking initiation, participants were asked “At what age did you first drink enough alcohol to feel drunk?” To assess their general drinking habits, participants were also asked to report the typical amount of alcohol they consume on each day of the week. These responses were summed to generate the typical amount of alcohol consumed on a weekly basis. To ascertain concurrent drinking and sex, participants were asked “In the past 12 months, how often have you consumed alcohol prior to or during sexual activity?” Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (about half the time) to 6 (all of the time).

Overview of data analytic strategy

Path analysis using Mplus statistical modeling software for Windows (version 4.0, Muthén & Muthén, 2004) with maximum likelihood estimation (ML estimator) was used to test the theoretical model (Figure 1). Latent variables were created for number of sexual partners and condom use during sexual events. Based on the theoretical model, the following path model was tested: the number of partners latent variable and the condom use latent variable were regressed on CSA severity, early consensual sex, and use of alcohol before sex. The use of alcohol before sex was regressed on current alcohol consumption habits. Current alcohol consumption was regressed on early drinking. Correlations were estimated between the number of partners and condom use latent variables. Correlations were also estimated among CSA severity, early consensual sex, and early drinking.

Results

Rates of childhood sexual abuse

Precisely a fifth of our sample of heterosexual men reported CSA that included physical contact(n = 56). Of the men that reported contact CSA, 26 reported that their most severe experience was fondling, 11 men reported that their most severe experience consisted of oral sex (performing or receiving), and 19 men reported experiences that included intercourse (penetrative or receptive).

Model specification

Bivariate correlations among the measured variables appear in Table 2. The measured variables were all related to one another in the expected direction. Factor loadings for the latent variables are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations among Measured Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSA Severity | -- | −.39*** | −.22*** | .02 | .00 | .24*** | .10* | .14** | .04 | .11* | .06 |

| 2. Age of First Consensual Sex | -- | .41*** | −.08 | −.10* | −.48*** | −.29*** | −.32*** | −.02 | −.09 | −.08 | |

| 3. Age of First Intoxication | -- | −.17** | −.05 | −.19** | −.11+ | −.07 | −.06 | −.09 | −.14* | ||

| 4. Current Alcohol Consumption | -- | .36*** | .07 | .16** | .00 | .02 | .03 | .04 | |||

| 5. Use of Alcohol Before Sex | -- | .21*** | .26*** | .12* | .11* | .19*** | .01 | ||||

| 6. # of Vaginal Sex Partners - Lifetime | -- | .59*** | .68*** | .01 | .06 | .13* | |||||

| 7. # of Sex Partners - Past Year | -- | .40*** | −.06 | .07 | .08 | ||||||

| 8. # of One-Time Sex Partners - Lifetime | -- | .01 | .04 | .11* | |||||||

| 9. Sex without a Condom – Past Year | -- | .53*** | .46*** | ||||||||

| 10. Condom Not Available – Past Year | -- | .52*** | |||||||||

| 11. Partner Not Want Condom – Past Year | -- |

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Factor Loadings for Latent Variables in the Model

| Raw Estimate | Std. Error | Z-Score | Std. Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Partners | ||||

| # of Vaginal Sex Partners - Lifetime | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .98 |

| # of Sex Partners – Past Year | 0.12 | 0.01 | 11.94 | .61 |

| # of One-Time Sex Partners – Lifetime | 0.29 | 0.02 | 13.62 | .71 |

| Condom Use | ||||

| Sex without a Condom – Past Year | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | .54 |

| Condom Not Available – Past Year | 1.69 | 0.21 | 8.04 | .74 |

| Partner Not Want Condom – Past Year | 1.53 | 0.19 | 8.22 | .72 |

Note.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

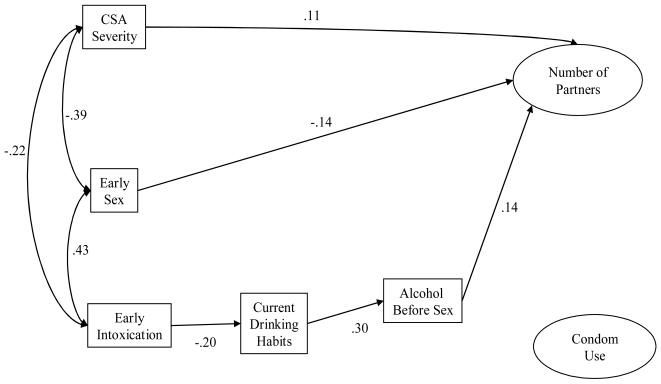

The hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2(35) = 54.952, p = .017, CFI = .976, TLI = .964, RMSEA = .037, SRMR = .040. Inspection of the path coefficients revealed that none of the hypothesized relationships between condom use and the predictor variables of CSA severity, early sex, and the use of alcohol before sex were significant, nor was the covariance between condom use and number of partners. These non-significant paths were fixed to zero, and the model was rerun. Illustrated in Figure 2, the final model also fit the data well, χ2(40) = 59.952, p = .022, CFI = .976, TLI = .969, RMSEA = .034, SRMR = .044. Chi-square difference testing (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) comparing the hypothesized model to the final model indicated that the final model fit the data as well as the hypothesized model, Δχ2(5) = 5.000, p = n.s. All of the paths that were free to vary in the final model remained significant. The final model accounted for 26% of the variance in number of partners.

Figure 2.

Testing indirect effects

Following procedures outlined by Bryan and colleagues (Bryan, Schmiege, & Broaddus, 2007), we tested the total indirect effect of early drinking on number of partners working through current alcohol consumption habits and the use of alcohol before sex. As predicted, the total indirect effect of early drinking on number of partners was significant (z = −2.212, p > .05).

Discussion

The present study examined relationships among history of childhood sexual abuse, risky sexual behavior, and an alcohol use pathway that may connect these two phenomena. The goal of this study was to extend prior research linking CSA to sexual risk-taking by using a community sample of heterosexual men, using a continuous definition of CSA based on severity, and by taking more alcohol-use variables into account. In the present study, severity of CSA was directly and indirectly, through its effect on alcohol use, associated with behaviors that increase one's level of STI risk.

Increasing severity of CSA was associated with an earlier age of drinking initiation. Findings of this sort, based on a dichotomous definition for CSA, have been reported in the past (Sartor et al., 2007). The current study expands previous findings by revealing that abuse severity, not just the presence of abuse, is predictive of younger drinking initiation. The precise function that alcohol serves for abused males is not well understood and likely depends on abuse-related and other environmental factors. Perhaps the abused youth uses alcohol to cope with psychological difficulties and to avoid the pain associated with the abuse. It is also possible that drinking and involving oneself with alcohol and other “adult” activities functions to increase a person's sense of self-esteem among their “less mature” peers. It may also be that a boy who has had sexual intercourse (for instance) simply “grows up” faster than their unabused peers and that alcohol use is simply a function of the social norms of “maturity.” In that vein, it has been reported that sexually abused males tend to fall away from pro-social peer groups and that the peer group that becomes favored is more oriented to anti-social activities (Bergen, Martin, Richardson, Allison, & Roeger, 2004), which may include underage drinking. In addition to investigating these speculations, future research should also examine if characteristics of the CSA experience other than type of sexual contact (e.g. sex of perpetrator, age at the time of abuse, alcohol use during abusive incident[s]) are likely to influence if and why a boy turns to alcohol at an early age. Regardless of why a person may begin using alcohol at an early age, prior studies have shown early use to be associated with elevated alcohol consumption later in life (e.g., Grant, Stinson, & Harford, 2001); a finding we observed as well. In our sample early drinking initiation was negatively associated with elevated levels of current alcohol consumption; earlier drinking age was predictive of heavier current use. It is worth noting that severity of abuse experience did not correlate with current levels of alcohol use, which suggests that higher levels of current consumption may likely be a product of longstanding habitual alcohol use versus using alcohol to emotionally cope, into adulthood, with the fallout from the abuse. Unsurprisingly, and in accordance with our conceptual model, in the context of elevated current drinking levels, participants reported more frequent use of alcohol prior to or during sexual intercourse.

In turn, those that reported more frequently having sex while under the influence of alcohol also reported having had more sexual partners. Possible explanations for this finding include alcohol myopia theory (Steele & Josephs, 1990) or reverse causation (that an individual is looking for a sexual partner, and that drinking establishments provide the most opportunities to find one). The finding that concomitant alcohol-use and sex is significantly associated with number of sexual partners, even while incorporating overall consumption rates in the model, seems to argue in favor of the former explanation. Specifically, if social drinking (i.e., being in a bar for example) alone is responsible for the effect, one would expect that the independent effect of concomitant alcohol and sex (while controlling for overall drinking) would be redundant and would not be statistically significant.

CSA severity also indirectly affected number of partners through earlier initiation of consensual sexual activities. At least in part, this is likely due to the latent variable structure of the dependent variable. The number of lifetime sexual partners one reported was incorporated into our number of partners latent variable. It is likely that those with longer sexual histories would report a greater number of sexual partners. Thus, in the full model, it is important to control for the length of time participants had been sexually active.

Notably, despite the inclusion of the alcohol variables and early sexual initiation in the model, CSA severity remained directly associated with the number of sexual partners participants reported. This finding underscores the complicated nature of the relationship between CSA and subsequent sexual risk-taking. It is possible that frequent sexual activity itself is particularly reinforcing for abused males and may function to allay psychological distress (Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998). Survivors' sexual motives should be explored and may help us understand the direct association between abuse and number of sexual partners.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the path between alcohol use during sex and condom use did not reach statistical significance. Again, increasing amounts of research are documenting the complexity of condom use decision-making. Contextual variables (e.g., partner type), which were not measured in the present study, seem to be extremely important and should be taken into consideration by future researchers attempting to understand factors influencing condom use.

Limitations and implications

There are several limitations to keep in mind with regard to the above results. Participants' self-report of sexual abuse was relied on. As such, the veracity of these reports is not guaranteed. Despite organizing the model in a temporal fashion, as suggested by Purcell et al.'s (2004) proposed model, these data were collected cross-sectionally and an unreported third variable may be responsible for the reported relationships. Sexual initiation and the alcohol variables were analyzed as single items which are subject to response errors and do not yield psychometric data. Additionally, the question regarding current drinking probed drinking in the past month and is used in the model to “predict” frequency of alcohol use before or during sex, which references the last year. Markers of severity such as frequency and duration of abuse, relationship to perpetrator, number of abusers, or use of force were not taken into account. Childhood socioeconomic status may have influenced outcome trajectory, but this domain was not assessed in the current study.

With regard to the relationships among CSA and the alcohol variables, another caveat must be stated. It is possible that the participants' experience with CSA came after their first experience of being intoxicated. This is because the cutoff age for CSA was 14 and we had some participants whom reported that their first drink came before age 14. It is likely that the number of participants for whom this is true is very small, for two notable reasons. The first reason is that the mean age for first intoxication was over 14. Secondly, the vast majority of boys that are abused experience CSA before they are age 11, and we only had two participants that reported being intoxicated before they reached 11 (Holmes & Slap, 1998).

It is worth noting that this is a difficult sample to characterize. In some respects, the sample possessed elevated risk indices---the sample was entirely comprised of drinkers and those not involved in a steady relationship. Conversely, excluding men with problem drinking (which may be related to abuse history) may serve to reduce risk, but would also be expected to dilute the findings and favor the null hypothesis. It is important to keep in mind that 20% of our sample reported CSA, which is higher than what is generally reported among heterosexual males. As such, while our results may not generalize to the entire male CSA population, our eligibility criteria do not seem to have reduced reported rates of abuse. Additionally, as noted above, not taking into account other characteristics of abuse impedes a comprehensive sample description. More research is needed to further substantiate this presumptive course of events---in which CSA triggers some kind of distress that a person tries to ameliorate with alcohol, which in turn elevates a person's level of risk. Future research should incorporate measures of drinking motives and sex motives to improve our understanding of how these behaviors function for male survivors of abuse. Longitudinal research would allow for more confidence with regard to causality. As mentioned in the method section, African-Americans were over-represented in the CSA sample. With this finding in mind, the racial make-up of the overall CSA sample was compared to the non-CSA sample and the results were non-significant when race was kept categorical and when race was analyzed dichotomously (white/non-white). Given these null findings, and the small African-American cell sizes, analyzing the effect race may have on outcome was deemed impossible to execute with this sample. However, the finding among African-Americans underscores the need of future investigators to recruit sufficiently diverse samples. Increased sample diversity will enable improved outcome analyses and will undoubtedly improve external validity.

Several implications are important to note. Of paramount importance is noting that CSA is not uncommon and is associated with problematic short-term and long-term consequences among non-clinical populations of heterosexual males. This highlights the need for early and ongoing assessment and intervention. Additionally, type of experience should be queried by assessors because more severe abuse seems to be associated with more detrimental outcomes. Second, care providers and family members of sexually abused boys should be especially vigilant regarding alcohol use. This may be an especially important point of intervention and may serve to interrupt a path that seems to lead to increased risky sexual decision-making. Pending future research on how alcohol functions in the lives of abused males, these findings may indicate that an alcohol and risk-reduction intervention tailored specifically for male survivors of CSA may be warranted. Third, given the null findings with regard to condom use, these findings suggest that in practice, while counseling alcohol-using male CSA survivors, interventionists should stress not only the importance of condom use, but the risks inherent in sleeping with a high number of different partners as well. Males remain vulnerable to STIs such as herpes despite using condoms. Further, having multiple sexual partners increases the likelihood that one or more of these partners is a casual partner with an unknown sexual history and/or sexual health status (Joffe et al., 1992).

In conclusion, the present study indicated that CSA among heterosexual male social drinkers is relatively common and that having been abused is associated with increased sexual risk-taking. Further, the observed increases in sexual risk-taking may partially be explained with an alcohol-use trajectory that may start early in a person's life. Taken together, the present findings underscore the need for early CSA assessment and intervention before a chronic and maladaptive pattern of alcohol use exacts a toll on the health of the abused male.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant AA13565 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to William H. George.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartholow BN, Doll LS, Joy D, Douglas JM, Jr., Bolan G, Harrison JS, Moss PM, McKirnan D. Emotional, behavioral, and HIV risks associated with sexual abuse among adult homosexual and bisexual men. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:747–761. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, Martin, Richardson, Allison, Roeger L. Sexual abuse, antisocial behaviour and substance use: Gender differences in young community adolescents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Zlotnick C, Cohn J. Impact of sexual abuse on the HIV-risk-related behavior of adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1413–1415. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS and Women. 2007 June 28; Retrieved January 23, 2009 from http://cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/print/overview_partner.htm.

- Chandy JM, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Gender-specific outcomes for sexually abused adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:1219–1231. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Shapiro CM, Powers AM. Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: a functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1528–1558. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Suppl. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Does drinking promote risky sexual behavior? A complex answer to a simple question. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR. Alcohol's effects on sexual decision making: an integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:843–851. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Hartwell T, Hansen N. Childhood sexual abuse and risk behaviors among men at high risk for hiv infection. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:214–219. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Sexually victimized children. The Free Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Futterman D, Hein K, Reuben N, Dell R, Shaffer N. Human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: The first 50 patients in a New York City program. Pediatrics. 1993;91:730–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Arends E. Sexual abuse and adolescent maladjustment: differences between male and female victims. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21:99–107. doi: 10.1006/jado.1997.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht R, Hendershot CS, Kajumulo K. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Barnett NP, Pedlow CT, Murphy JG. Drinking in conjunction with sexual experiences among at-risk college student drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:697–705. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger ME, Leeb RT, Swahn MH. Childhood maltreatment and early alcohol use among high-risk adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:291–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, George WH. Alcohol and sexuality research in the AIDS era: trends in publication activity, target populations and research design. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual abuse of boys: Definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe GP, Foxman B, Schmidt AJ, Farris KB, Carter RJ, Neumann S, Tolo KA, Walters AM. Multiple partners and partner choice as risk factors for sexual transmitted disease among female college students. Sexually Transmitted Disease. 1992;19:272–278. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, De La Rosa M, Trepka MJ, Kelley M. Condom use among unmarried students in a Hispanic-serving university. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:448–461. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM. The effects of alcohol and expectancies on risk perception and behavioral skills relevant to safer sex among heterosexual young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:476–485. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Mplus Technical Appendices. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy S, Adcock AG, Nagy MC. A comparison of risky health behaviors of sexually active, sexually abused, and abstaining adolescents. Pediatrics. 1994;93:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:294–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R. Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The urban men's health study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:557–584. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Malow RM, Dolezal C, Carballo-Die'guez A. Sexual abuse of boys: Short- and long-term associations and implications for HIV prevention. In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O'Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, De Luca RV. Male sexual abuse: A review of effects, abuse characteristics, and links with later psychological functioning. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell S. Teenage pregnancy and associated risk behaviors among sexually abused adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:98–105. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.98.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, McCutcheon VV, Nelson EC, Waldron M, Heath AC. Childhood sexual abuse and the course of alcohol dependence development: findings from a female twin sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:720–731. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner SA, Norris J, George WH, Morrison DM, Zawacki T, Davis KC, Hessler DM. Women's condom use assertiveness and sexual risk-taking: Effects of alcohol intoxication and adult victimization. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dorn RA, Mustillo S, Elbogen EB, Dorsey S, Swanson JW, Swartz MS. The effects of early sexual abuse on adult risky sexual behaviors among persons with severe mental illness. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1265–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women's substance abuse: National survey findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Francis KJ, Straatman AL. Child abuse in religiously-affiliated institutions: long-term impact on men's mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]