Abstract

The mucolipin family of Transient Receptor Potential (TRPML) proteins is predicted to encode ion channels expressed in intracellular endosomes and lysosomes. Loss-of-function mutations of human TRPML1 cause type IV mucolipidosis (ML4), a childhood neurodegenerative disease. Meanwhile, gain-of-function mutations in the mouse TRPML3 result in the varitint-waddler (Va) phenotype with hearing and pigmentation defects. The broad spectrum phenotypes of ML4 and Va appear to result from certain aspects of endosomal/lysosomal dysfunction. Lysosomes, traditionally believed to be the terminal “recycling center” for biological “garbage”, are now known to play indispensable roles in intracellular signal transduction and membrane trafficking. Studies employing animal models and cell lines in which TRPML genes have been genetically disrupted or depleted have uncovered roles of TRPMLs in multiple cellular functions including membrane trafficking, signal transduction, and organellar ion homeostasis. Physiological assays of mammalian cell lines in which TRPMLs are heterologously over-expressed have revealed the channel properties of TRPMLs in mediating cation (Ca2+/Fe2+) efflux from endosomes and lysosomes in response to unidentified cellular cues. This review aims to summarize these recent advances in the TRPML field and to correlate the channel properties of endolysosomal TRPMLs with their biological functions. We will also discuss the potential cellular mechanisms by which TRPML deficiency leads to neurodegeneration.

Keywords: transient receptor potential (TRP) channel, endosomes, lysosomes, TRPML, membrane traffic, intracellular channel

Introduction

The endolysosome system in the cell is comprised of early endosomes (EEs), recycling endosomes (REs), late endosomes (LEs), and lysosomes (LYs) and is essential for a variety of cellular functions including membrane trafficking, protein transport, autophagy, and signal transduction (reviewed in Refs. [1,2]). EEs are derived from the plasma membrane upon endocytosis and are involved in intracellular trafficking of components that are sorted into recycling endosome or late endosome pathways (Fig. 1). Lysosomes are membrane-enclosed compartments that are derived from LEs and filled with hydrolytic enzymes. A hallmark feature of the endolysosome system is an acidic pH in the lumen (luminal pH is approximately 6, 5.5, and 4.5 in the EE, LE, and LY, respectively), which is established and maintained by the V-ATPase H+ pump [2]. The membrane potentials of endosomes or lysosomes are not precisely known but are presumed to be positive in the lumen (approximately in the range of + 30 to +110 mV) based on measurements from other related acidic organelles [1]. Similar to other intracellular organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [3], endolysosomes also provide storage for intracellular Ca2+ and have a luminal Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]lumen) of approximately 0.5 mM [4]. An unidentified H+-Ca2+ exchanger is thought to maintain the intraendolysosomal Ca2+ gradient at the expense of the H+ gradient [1,2,5]. The release of Ca2+ from endolysosomes may play important roles in signal transduction [6,7] and membrane trafficking [2,5,8]. Although it is known that lysosomes frequently fuse with the plasma membrane and other intracellular membranes such as endosomes, autophagosomes, and phagosomes under resting conditions or upon cellular stimulation, the mechanisms underlying fusion events are not well established. While Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptors (SNAREs) are essential structural components involved in intracellular trafficking (e.g., membrane fusion and fission) [9], both small GTPase Rabs [10] and phosphoinositides (PIPs) [11] function as important regulatory players. In addition, the level of juxta-organellar Ca2+ also plays a central role in regulating membrane trafficking [12,13]. However, the ion channels . responsible for intralysosomal Ca2+ release have still remained elusive. Candidate endolysosomal Ca2+ channels include several members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) protein family (i.e. TRPMLs, TRPV2, and TRPM2) and the recently identified two-pore Ca2+ channels (TPCs) [1,6,7].

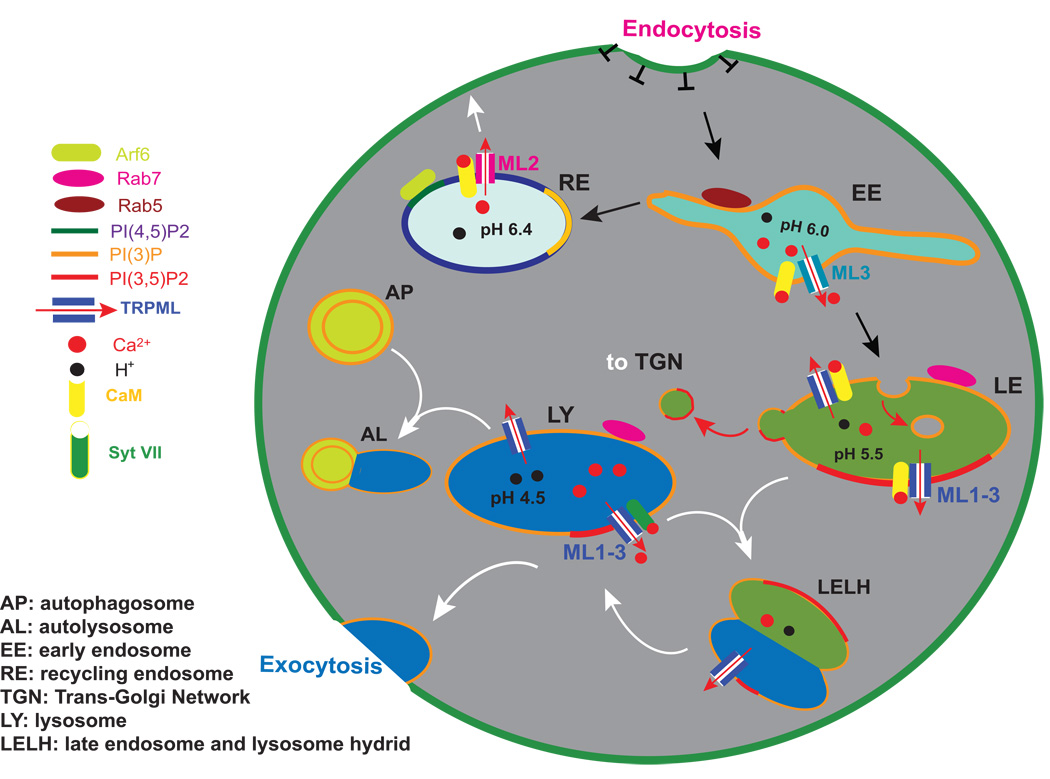

Figure 1. TRPMLs in the endocytic pathway.

Intracellular compartments undergo cargo-dependent maturation (indicated by black arrows), membrane fusion (white arrows), and fission/budding (red arrows). The molecular identities of intracellular compartments are defined by specific recruitment of small G proteins (Rab and Arf GTPases) and the composition of phosphoinositides (PIPs). Endolysosomes are Ca2+ stores with luminal Ca2+ concentration estimated to be approximately 0.5 mM. The pH of each organelle is indicated. In endolysosomes, TRPML-mediated intra-endosomal Ca2+ release may activate Ca2+ sensor proteins such as Synaptotagmin (Syt) and calmodulin (CaM) to trigger homotypic and heterotypic fusion. TRPML3 is present in early endosomes (EEs; pH 6.0; PI(3)P; Rab5), which are derived from the primary endocytic vesicles after endocytosis. In addition to the late endocytic pathway, contents in the EE can also be sorted into recycling endosomes (RE; pH 6.4), which are subsequently recycled back to the plasma membrane. TRPML2 is present in Arf6 – positive REs. The channel activity of TRPML2 (in RE) may regulate the activation of small GTPase Arf6, an important regulator of the recycling pathway. EEs can undergo maturation (membrane trafficking) to become late endosomes (LEs; pH 5.5; PI(3)P+PI(3,5)P2; Rab7). Membrane proteins enter the degradation pathway following membrane invagination to form multi-vesicular bodies (MVB) in LEs. LEs can fuse with LYs (LYs; pH 4.5; PI(3)P+PI(3,5)P2; Rab7) to form LE-LY hybrids. LYs can then be reformed from LE-LY hybrids. Other than fusion with LEs, LYs can also undergo fusion with autophagosomes (APs) to form autolysosomes (ALs) or with the plasma membrane during lysosomal exocytosis. TRPML1-3 channels are predominantly localized in LEs and LYs. Activation of TRPML channels by unidentified cellular cues may induce intralysosomal Ca2+ release. LEs, LYs, or hybrids of LEs and LYs will then undergo CaM- or Syt- dependent membrane fusion or fission/budding. Retrograde transport vesicles, derived from EEs, LEs, or LYs upon membrane fission transport lipids and proteins in a retrograde direction to the trans-Golgi Network (TGN).

Emerging evidence suggests that the mucolipin subfamily of TRP proteins (TRPMLs) consists of endolysosomal cation channels. TRP channels are a large family of cation channels with diverse physiological functions particularly in sensory signaling [14–16]. Similar to all other TRPs, TRPMLs are 6 transmembrane (6TM)-spanning proteins that consist of cytosolic N-and C- termini (see Fig. 2 for membrane topology). In mammals, there are three TRPML proteins (TRPML1–3, also called MCOLN1–3). Loss-of-function mutations in the human TRPML1 gene cause Type IV Mucolipidosis (ML4), a devastating neurodegenerative disease that causes mental retardation and retinal degeneration [17–19]. In addition, some patients also develop iron deficient anemia [18]. Gain-of-function mutations of the mouse TRPML3 gene result in the varitint-waddler (Va) phenotype that is characterized by deafness, circling behavior, and pigmentation defects [20]. The broad spectrum of phenotypes for both ML4 and Va appears to result from certain aspects of endosomal/lysosomal dysfunction. TRPML1−/− cells from ML4 patients are characterized by the accumulation of enlarged endosomal/lysosomal compartments (vacuoles) in which lipids and other biomaterials accumulate, suggesting defective lysosomal biogenesis and trafficking [21,22]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms of TRPMLs that are required for normal lysosomal functions are not known largely due to the lack of reliable physiological assays. Conventional assays used for assessing plasma membrane channels, such as the whole-cell patch-clamp technique, are not suitable for studying TRPMLs due to the inaccessible nature of the lysosome. Fortunately, this technical barrier has recently been overcome in a new series of studies using an activating mutation strategy [23–26]. In addition, a modified patch-clamp technique has been developed that allows a direct recording on lysosomal membranes [27,28]. This review aims to summarize recent advances in the field and to correlate the channel properties of endolysosomal TRPMLs with their currently established biological functions.

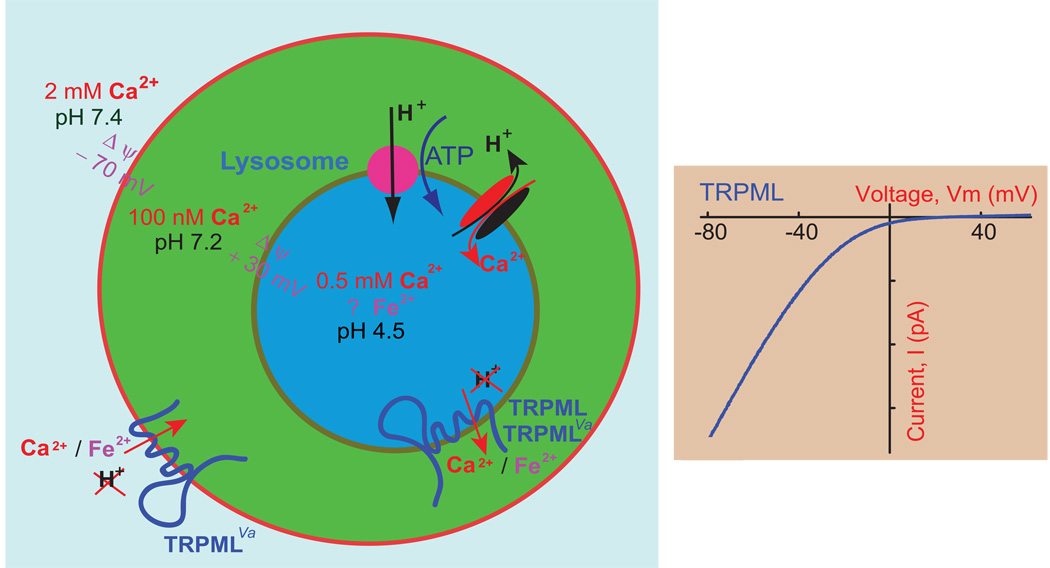

Figure 2. TRPMLs in the lysosome.

A) While the ionic compositions of the extracellular space and cytosol have been well established, ion concentrations in the lumen of lysosomes are not clear. The luminal pH is between 4 and 5 and is established by a V-type ATPase. The [Ca2+]LY is approximately 0.5 mM and maintained by an unidentified H+-Ca2+ exchanger. The resting membrane potential (Δφ) of the cell is approximately −70 mV (cytoplasmic-side negative). Based on studies of phagosomes, the membrane potential across the lysosomal membrane is estimated to be approximately + 30 mV (luminal-side positive). TRPMLs are permeable to Fe2+ (except for TRPML3) and Ca2+; none of the TRPML isoforms are permeable to H+. Although wild-type TRPMLs are predominantly expressed in the lysosome, TRPMLVaproteins are present at the plasma membrane. B) Current-voltage (I–V) relationship of TRPML channels. All TRPMLs exhibit a strong inward rectification.

TRPML tissue distribution and subcellular localization

In order to gain insight into the biological functions of TRPMLs, it is important to know the relative expression levels of each individual isoform in specific tissues. Unfortunately, most of the available TRPML antibodies are inadequate for this purpose and therefore published data have measured TRPML mRNA expression levels using nucleotide-based techniques such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), northern blot, and in situ hybridization. In mammals, TRPML1 is expressed in every tissue with the highest levels of expression located in the brain, kidney, spleen, liver, and heart [19] (Table 1). Consistent with its ubiquitous expression pattern, the enlarged vacuole phenotype that is associated with the loss of TRPML1 is observed in all cell types of ML4 patients and TRPML1 knockout mice [17,29]. In contrast to TRPML1, the expression of TRPML2 and TRPML3 is more restricted (Table 1). Mouse TRPML2 has two alternatively spliced variants [30]. The longer variant of TRPML2 (TRPML2lv) has an additional 28 amino acids at its N terminus compared to the shorter variant (TRPML2sv) [30]. Real-time PCR analysis revealed that TRPML2sv has a higher expression level than TRPML2lv in most tissues and is the dominant variant expressed in mouse thymus, spleen, and kidney [30]. TRPML3 mRNA is detectable in the thymus, lung, kidney, spleen, and eye [30,31] and the protein was found to be expressed in hair cells of the cochlea [20,23] and melanocytes of the skin [32] using TRPML3-specific antibodies for detection. TRPML3 protein was also detected in several epithelial cell lines including HEK293, HeLa, and the retinal pigmented epithelial cell line ARPE19 [33–35]. Interestingly, the expression level of TRPML2, but not TRPML3, is altered in a tissue-specific manner in TRPML1−/− cells [30]. It is likely that the three isoforms of mammalian TRPMLs have unique tissue-specific functions in addition to their shared cellular functions. In contrast to mammals, Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans only express one TRPML protein [36,37].

Table 1.

The Mammalian TRPML Channels

| TRPML1 (MCOLN1) |

TRPML2 (MCOLN2) |

TRPML3 (MCOLN3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Expression | Ubiquitously | Thymus, liver, kidney, heart, spleen |

Cochlea, thymus, kidney, lung, eye, spleen, skin (melanocytes), somato-sensory neurons |

|

Subcellular localization |

Late endosome and lysosome (LEL) |

Recycling endosome, LEL |

Plasma membrane, early endosome, LEL |

| Ion selectivity | Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mn2+, Fe2+, Mg2+, Zn2+, etc. |

Na+, K+, Ca2+, Fe2+ | Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ |

|

Current-Voltage Relationship (I–V) |

Strong inwardly rectifying | Strong inwardly rectifying |

Strong inwardly rectifying |

|

Single channel conductance in pS |

76 (from −140 to −100 mV) and 11 (from −80 to −40 mV) |

Not Described | ~50 |

|

Activation mechanisms |

Voltage; NAADP (?); PKA (?); extracellular or luminal low pH |

Voltage; extracellular or luminal low pH |

Voltage; Na2+ removal followed by re-addition |

|

Blockers and inhibitors |

Verapamil; Gd3+; La3+ | Not Described | Verapamil; Gd3+; extracellular or luminal low pH |

|

Interacting proteins |

TRPML2; TRPML3; Hsc70; Hsp40; ALG-2 |

TRPML1; TRPML3 |

TRPML1; TRPML2 |

| Cellular functions | Membrane trafficking in late endocytic pathways; autophagy; lysosomal biogenesis; lysosomal iron release; lysosomal exocytosis; possible LEL pH homeostasis |

Membrane trafficking in late endocytic pathways and Arf6-regulated recycling pathway |

Membrane trafficking along endolysosomal pathways; autophagy; possible hair cell function |

| Human Disease | Mucolipidosis type IV (ML4; MIM #252650; autosomal recessive lysosomal storage neurodegenerative disease with progressive psychomotor retardation, retina degeneration, iron deficiency, achlorhydria, and mental retardation); ML4 cells show enlarged endolysosomes, lipid accumulation, autophagic dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction, possible acidification defect, and lipofuscin accumulation in the brain |

Not Described | Not Described |

| Genetic models | 1) TRPML1 knockout mice: inclusion bodies, enlarged vacuoles, psychomotor defect, retinal degeneration, death at age approximately 8 months 2) Cup-5 null C. elegans: enlarged vacuoles, excess apoptotic cells, and embryonic lethality 3) Drosophila trpml mutant: defective autophagy, impaired synaptic transmission, accumulation of apoptotic cells, oxidative stress, lipofuscin accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, motor defects, and massive neurodegeneration |

Not Described | Varitint-waddler mouse (Va) with A419P mutation in the 5th TM domain; Va(J) mouse with an additional mutation at I362T; Heterozygous and homozygous mice exhibit pigmentation defects in the skin, circling behavior with degeneration of vestibular apparatus, and low fertility |

| References | [18,19,22,26– 30,32,36,40,48,53,63,79–82] |

[26,30,32,42,44] | [20,23,25,26,30,32,34,35,46,83] |

TRPMLs primarily localize to a population of membrane-bonded vesicles along the endocytosis and exocytosis pathways. Overexpression studies using TRPML1 tagged or fused with reporter genes, such as EGFP or mCherry, have revealed that TRPML1 primarily localizes to the lysosome-associated membrane protein (Lamp-1) or Rab7- positive late endosomal and lysosomal (LEL) compartments [28,34,35,38–43]. TRPML1 localization to the LEL has been beautifully confirmed by immunostaining and gradient fractionation studies on endogenous proteins [33,35]. Lysosomal localization of TRPML1 protein is likely mediated by Clathrin adaptor AP2-dependent internalization from the plasma membrane and/or AP1/AP3-dependent trafficking from the trans-Golgi Network (TGN) by direct interaction with two individual di-leucine motifs that exist near the N- and C- termini of TRPML1 [40,42,43].

Similar to TRPML1, TRPML2 and TRPML3 that were tagged and overexpressed also co-localize with Lamp-1 and Rab7 in LEL compartments [34,35,41,44,45]. Immunolocalization studies have also shown that TRPML2 localizes to the vesicles along the long, tubular structures within cells in addition to the LEL [44]. These long, tubular structures correspond to the recycling endosomes of the GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor-6 (Arf-6) associated pathway [44]. By using cellular fractionation and primary antibodies specific to TRPML3, Kim et al. demonstrated that TRPML3 localizes to LELs, EEs, and the plasma membrane [35]. The plasma membrane localization of TRPML3 is consistent with the substantial whole cell currents that can be recorded from TRPML3-expressing HEK293 cells [24,25].

Channel properties of TRPMLs

TRPML1 and TRPML2 are primarily localized to the LEL, making it difficult to characterize their channel properties. In contrast, overexpressed, wild-type TRPML3 is present at the plasma membrane and has been characterized using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique [24,25]. These studies have shown that TRPML3 is an inwardly rectifying, Ca2+-permeable cation channel (thoroughly reviewed in Ref. [31]) . TRPML3-mediated current (ITRPML3) is inhibited by an acidic extracellular (analogous to the luminal side) pH with H+ presumably binding to multiple histidine residues within the TM1-TM2 loop [46]. Interestingly, ITRPML3 is potentiated by the removal and subsequent re-addition of extracellular Na+ [25,46]. The physiological implications of these two observations remain to be established. Mutation of mouse TRPML3 (A419P) causes the varitint-waddler (Va) phenotype, which is characterized by deafness, circling behavior, and pigmentation defects [20]. Much larger currents were seen for TRPML3A419P (TRPML3Va) compared to wild-type TRPML3 [24]. ITRPML3-Va resembles ITRPML3 in the basic channel pore properties including current-voltage (I–V), single channel conductance, and ion selectivity [23,25,32]. However, since ITRPML3-Va cannot be further activated by Na+ manipulation [25], the Va mutation is likely to disrupt channel gating by locking the channel in an open state [31]. Therefore, the reported Va-induced small alteration of Ca2+ permeability [46] could be secondary to the effect on gating. This would be in accordance with the gating-permeation coupling theory recently proposed for other TRPs [47].

The Va activating-mutation approach has been used to effectively characterized the pore properties of TRPML1 and TRPML2 in multiple studies [26,28,30,32]. Introduction of Va-like mutations in the analogous positions of TRPML1(V432P) and TRPML2 (A396P) allowed for the characterization of the pore properties of TRPML1 and TRPML2 using whole-cell recordings [27,28,30,32]. We initially reported that TRPML2sv-Va was functional but TRPML2lv-Va was not [24,28]. However, a single mutation in our original mouse TRPML2lv-Va clone might have actually been a cloning artifact (as opposed to a polymorphism as originally thought), since correction of this mutation resulted in a measurable inwardly rectifying whole-cell current [30] (personal communication with M. Cuajunco and C . Grimm). Similar to ITRPML3, both ITRPML1-Va and ITRPML2-Va are inwardly rectifying and Ca2+-permeable cationic currents. Using a lysosome patch-clamp technique, Dong et al. were able to characterize wild-type TRPML1 [28] and TRPML2 (Dong et al., unpublished results) in their native membranes (LEL). Lysosomal ITRPML1 and ITRPML2 exhibited almost identical pore properties (I-V, kinetics, and voltage-dependence) as their respective Va mutant channels, supporting the hypothesis that the activating mutation (Va) is a useful approach for characterizing the pore properties of TRPML1 and TRPML2. Nevertheless, whole lysosome ITRPML1-Va is at least 10 times larger than whole lysosome ITRPML1 [28], suggesting that Va is also a gain-of-function mutation in LEL. Previous studies have resulted in very controversial results on the channel properties of TRPML1 (summarized in Ref. [21]). However, the reported currents from these studies contrast dramatically with ITRPML1 and ITRPML1-Va data described above. For example, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of overexpressed TRPML1 were reported to yield outwardly rectifying monovalent, cation-selective [38] or H+-selective [48] channels. ITRPML and ITRPML-Va, however, are inwardly rectifying and permeable to Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Fe2+/Mn2+, but not H+ [24,27,28]. Although differences may exist for ion channel studies using different heterologous expression systems, it is unlikely that different laboratories cannot reach a consensus on the basic pore properties of one single channel protein. In the view of the authors of this article, the inwardly rectifying currents (under physiological conditions) are likely to represent the true electrophysiological functions of TRPMLs. Consistent with the overexpression studies, the endogenous TRPML-like current in LEL is also strongly inwardly rectifying (Dong et al., unpublished results).

Although the pore properties of TRPMLs have been well characterized, the mechanisms of how TRPMLs are gated/activated under physiological conditions are not known. Since the Va mutation appears to lock TRPML channels in the open state [25,31], studies of ITRPML-Va may not yield useful information regarding TRPML regulation. ITRPML1-Va and ITRPML2-Va are both potentiated by low pH, however the effect is quite modest [24,28]. In addition, H+ may have increased the single channel conductance but most likely did not increase the open probability of the channels. Therefore, the physiological implication of this pH modulation remains to be established. Heterologously-expressed wild-type TRPML3 is present in the plasma membrane [24,25,35], which allows for the study of channel activation mechanisms. Wild-type TRPML1 and TRPML2 might also be able to traffic to the plasma membrane under certain conditions or in specific cell types, though these situations have not been reported. Another possible method for investigating TRPML gating is to analyze lysosome recordings. Using this method, we are currently studying how over-expressed and endogenous TRPMLs are regulated by luminal and cytosolic factors that are known to affect lysosomal functions (Dong et al., unpublished findings). For TRPML3, Kim et al. was able to investigate the activation mechanisms of ITRPML3 using whole-cell recordings and reported that ITRPML3 is dramatically enhanced by Na+ manipulation (removal followed by re-addition) [25]. However, it remains to be established how TRPML3 is activated by mechanisms that are physiologically more relevant.

TRPML in membrane trafficking

Human ML4 mutations cause the abnormal accumulation of sphingolipids, phospholipids, acidic mucopholysaccharides, and cholesterol in swollen/enlarged LEL-like vacuoles in all cell types [22,49]. Consistent with this observation, abnormal lipid accumulation and enlarged LELs are also seen in cells from TRPML1 knockout mice [29], TRPML−/− (cup-5) C. elegans [37], and TRPML−/− Drosophila [36]. Electron microscopy (EM) studies suggest that enlarged LELs in TRPML−/− cells are likely to be the late endosome-lysosome hybrid organelles from which lysosomes are reformed under normal conditions [50]. Since the hydrolase activity that is involved in lipid processing is relatively normal, the defect observed in TRPML−/− cells is most likely related to the sorting and trafficking processes of the endocytic pathway [22]. Analyses of trafficking kinetics suggest that the defect is in the late endocytic pathways only [22]. Specifically, the exit of lipids from the LEL to the TGN is defective in ML4 cells [22,40]. In support of these obervations, shRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPML1 expression in mouse macrophages results in a similar defect in retrograde lipid transport [41]. Taken together, TRPML1 is likely to be required for the formation of transport vesicles from the LEL compartment to the TGN and for the reformation of lysosomes from the late endosome-lysosome hybrid organelles [37,41,50]. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that TRPML1 expression is dramatically increased following induction of lysosome biogenesis [51]. Since membrane fission and/or stabilization of transport vesicles are known to be dependent on luminal Ca2+ [2,5,52] and/or intraluminal Ca2+ release [5,13], it is likely that the Ca2+ permeability of TRPML1 is required for the membrane fission from LEL compartments or late endosome-lysosome hybrids and the biogenesis of both retrograde transport vesicles and lysosomes (Fig. 1). TRPML1 may also be required for the reformation of lysosomes from autolysosomes [36,53].

Other trafficking defects are also observed in TRPML−/− cells. ML4 fibroblasts have been reported to exhibit a delay in the delivery of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) to lysosomes [53]. In mouse macrophages where TRPML1 protein level has been reduced by shRNA, the transport of endocytosed molecules to lysosomes is delayed [41]. Autophagosomes have also been shown to accumulate in ML4 cells. This could be due to either increased autophagosome formation or delayed fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes to form autolysosomes (AL) (Fig. 1) [53]. ML4 fibroblasts also show a defect in ionomycin-induced lysosomal exocytosis [54]. However, this effect could be a secondary observation, since ionomycin (Ca2+ ionophore) presumably acts directly on the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin VII (SytVII) thereby bypassing upstream TRPML activation. Nevertheless, experiments showing that HEK293 cells transfected with a gain-of-function mutant TRPML1 exhibit enhanced lysosomal exocytosis provide additional evidence that TRPML1 plays a role in this process [27]. The gain-of-function mutation is likely to have mimicked an unidentified cellular stimulation to induce intralysosomal Ca2+ release since these experiments were performed using a Ca2+-free extracellular solution to exclude the involvement of the gain-of-function TRPML1 channels at the plasma membrane. Taken together, we hypothesize that TRPML1 plays a role in multiple membrane fusion processes related to late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 1). Membrane fusion in the endocytic pathway is dependent on the release of luminal Ca2+ that occurs as a post-docking event [55]. Using Ca2+ chelators in cell-free assays, Pryor et al. showed that luminal Ca2+ is required for both lysosome reformation and heterotypic fusion of late endosomes and lysosomes [13]. Release of luminal Ca2+ is thought to promote the post-docking events through the activation of Calmodulin (CaM) [13]. In consideration of these data, it is possible that TRPML1 may be tightly regulated to release Ca2+ as a mechanism of facilitating the endocytic process in a correct spatiotemporal method. TRPML1, therefore, may play a dual role in membrane fusion and fission in the late endocytic pathways (late endosomes, lysosomes, autophagosomes, and the plasma membrane).

In comparison to TRPML1, the role of TRPML2 and TRPML3 in regulating membrane trafficking is less well understood. TRPML2 and TRPML3 may function indirectly through the formation of heteromultimers with TRPML1, since both heterologously-expressed [42] and endogenous TRPMLs [56] can physically associate with each other (Table 1). However, the extent of co-localization appears to be limited [33]. Therefore, it is more likely that TRPML2 and TRPML3 functions are primarily cell type specific. In LEL, it is reasonable to hypothesize that TRPML2/3 play a similar role in membrane trafficking as TRPML1. TRPML2 has been reported to traffic via the Arf6-associated recycling pathway in Hela cells [44]. While overexpression of TRPML2 promotes efficient activation of Arf6, inactivation of TRPML2 by a dominant-negative approach decreases recycling of CD59 proteins to the plasma membrane [44]. Thus, TRPML2 may interact and cross-talk with other trafficking regulators to control cargo sorting. The localization of TRPML3 is more dynamic with expression in multiple intracellular compartments. The diverse expression of TRPML3 may correlate with its role in membrane trafficking [34,35]. Overexpression of TRPML3 causes enlarged early-endosome-like structures and defective delivery and degradation of EGF and EGFR that is consistent with its expression in EEs [34,35]. Since heterologously-expressed TRPMLs display basal activity in the LEL [28], it is possible that overexpression of TRPML3 promotes endosomal membrane fusion. Interestingly, knockdown of TRPML3 appears to enhance endocytosis and degradation [34], a result that is inconsistent with the role of TRPML1 in degradation and trafficking in the late endocytic pathways [22,40,41]. It is possible that this observed effect is due to a function of TRPML3 in early endocytic pathways. The exact step where TRPML3 functions in the early endocytic pathway is still not clear. While Kim et al. showed that TRPML3 overexpression decreases constitutive and regulated endocytosis in HEK and HeLa cells [35], Martina et al. found that internalization of EGFR is not affected but that its delivery from the plasma membrane to the lysosome is impaired in human epithelial cells [34]. It is possible that these observed differences are due to the use of different cell types. Finally, TRPML3 may also be involved in the regulation of autophagy since both overexpression and knockdown of TRPML3 inhibit autophagy [34,35].

It is yet unclear how TRPMLs coordinate with the other key regulators of vesicle trafficking such as GTPases (Rab and Arf) and phosphoinositides since the endogenous activators of TRPMLs have not been identified. Constitutive activation of Rab5 causes enlarged early endosomes by stimulating homotypic fusion [10]. This is reminiscent of the enlarged endosomes seen in cells with TRPML3 overexpression. It is possible that Rab5 may recruit effectors to activate TRPMLs. Alternatively, the activity of TRPMLs may regulate the activity of Rabs, as shown in the case of TRPML2 and Arf6 GTPase [44]. Similarly, alterations of endolysosomal phosphoinositide (PIP) levels (PI(3)P and PI(3,5)P2) also results in enlarged endolysosomes and defective endosome-to-TGN retrograde trafficking [11], a situation that is similar to the enlarged LEL and abnormal late endocytic trafficking phenotype seen in ML4 cells. It is possible that TRPMLs are regulated directly by PIPs as shown for many other plasma membrane TRPs [57]. Alternatively, TRPMLs may regulate key enzymes involved in PIP production or hydrolysis. Taken together, TRPMLs may cross-talk with these proteins and/or lipids to regulate endolysosomal traffic. Since membrane trafficking is an active process, we expect that TRPMLs would be frequently activated in the intact cell, unlike the situation in a lysosome recording configuration in which there is not substantial channel activity. It is worth noting that like most other TRPs, overexpressed TRPMLs tend to exhibit basal currents. However, as TRPMLs do not exhibit significant voltage-dependent inactivation, even a small TRPML current may lead to substantial Ca2+ release. Therefore, it is necessary for TRPMLs to be tightly regulated in the lysosome. It is likely that TRPMLs are only transiently activated in the intact cell. TRPML-mediated channel activation may be able to be captured as “spontaneous” lysosomal Ca2+ release events using high-resolution, live imaging techniques in the near future. Different Ca2+ sensors might be recruited in a compartment-specific manner downstream of Ca2+ release. While CaM has been reported to be functional in late endosomes [13,55,58], SytVII might convert the signal into Ca2+-dependent fusion with the plasma membrane [59]. Recently, Vergarajauregui et al. reported that ALG-2, a penta-EF-hand protein, physically associated with TRPML1 but not TRPML2 or TRPML3 [60]. ALG-2 might also serve as a Ca2+ sensor to couple TRPML1 activation to endolysosomal fusion/fission events. Interestingly, the interaction of TRPML1 and ALG-2 is strongly dependent on Ca2+ [60], suggesting that this interaction is physiologically significant. Future research may indicate whether ALG-2 also plays a role in the modulation of TRPML channel activity in the LEL.

TRPMLs in signal transduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that a modest Ca2+ release from lysosomes plays an indispensable role in the transduction of extracellular signals by inducing a large and rapid release of Ca2+ from the ER through the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) or ryanodine receptor (RyR) [7,61]. However, the mechanisms by which Ca2+ is released from lysosomes has remained elusive. There are two significant questions that remain unanswered. First, it is not known which intracellular messenger is generated upon extracellular stimulation. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) has been an attractive candidate that is believed to induce Ca2+ release from lysosomes [7,61]. Second, identification of the lysosome Ca2+ channels that are activated by NAADP and other lysosome-acting cytosolic factors remains elusive. TRPMLs could potentially be the lysosomal Ca2+ release channels based on their subcellular location and Ca2+ permeability. Zhang et al. recently showed that a NAADP-sensitive current could be blocked by an anti-TRPML1 antibody or reduced by TRPML1-specific siRNA using reconstituted lipid bilayers from biochemically purified lysosomal membranes [62,63]. One caveat of these studies is that the NAADP-activated current was Cs+ permeable and possessed a linear I–V, two properties not shared by ITRPML1. Nevertheless, ET-1, a known NAADP stimulator in coronary arterial myocytes [62], was found to induce a local Ca2+ release from lysosomes followed by a global Ca2+ rise [64]. This response was significantly reduced after pre-treatment with TRPML1-specific siRNA [62]. It is possible that TRPML1 may form heteromultimers with other candidate NAADP receptors such as TPCs [7]. Future work will be required to clarify the role of TRPML1 in lysosomal Ca2+ signaling that is mediated by NAADP or other lysosome-acting intracellular messengers.

TRPMLs in endolysosomal H+ homeostasis

Lysosomal H+ homeostasis is known to play an essential role in multiple lysosome-mediated functions. First, a change of luminal pH may dramatically affect the functions of acidic hydrolytic enzymes in the lysosome and impair the degradative functions occurring in the lysosome [5]. Second, similar to Ca2+, luminal H+ is known to affect membrane fusion/fission via unknown mechanisms [2,5]. Recently, Miedel et al. developed an alternative model to explain ML4 pathogenesis based on the evidence that lysosomal pH in ML4 cells or cells treated with TRPML1-specific siRNA is lower than in normal cells [48,65]. This new model is referred to as the “metabolic model” as opposed to the aforementioned “biogenesis” or “trafficking” model. The central idea of the “metabolic model” hypothesizes that a decreased lysosomal pH may interfere with the degradation of internalized lipids since H+ ions are important for sorting processes and proper function of lysosomal acid hydrolases. If this model is proven to be correct, enzyme therapies would be an effective method to treat ML4 [65].

Despite data supporting this newly proposed model, there are several observations that contradict this hypothesis. Firstly, it is not immediately clear what causes lysosomal hyperacidification in the absence of TRPML1 given that ITRPML and ITRPML-Va exhibit no permeability to protons [24]. However, although ITRPML3 is H+-impermeable and is indeed suppressed by low pH, overexpression of TRPML3 results in the alkalization of endo-lysosomes [34]. Therefore, it is likely that H+ homeostasis is regulated by intralysosomal Ca2+ release possibly through an unidentified Ca2+-H+ exchanger. Leucine zipper/EF hand-containing transmembrane-1 (Letm1), the recently identified mitochondrial Ca2+-H+ exchanger, can function in a bidirectional manner [66]. Similarly, TRPML-mediated juxtaorganellar [Ca2+]cyt elevation may induce H+ efflux through a lysosomal counterpart of Letm1. It remains to be determined whether lysosomal hyperacidification associated with loss of TRPML1 is caused by such indirect mechanisms. Secondly, reduction of lysosomal pH in ML4 cells is still controversial [40] since hypoacidification and no change of lysosomal pH have also been observed in ML4 cells [22,67]. Impaired H+ homeostasis may affect the activity of a Ca2+-H+ exchanger and/or luminal Ca2+ buffering and could lead to impaired Ca2+ homeostasis. However, lysosomal Ca2+ content appears to be normal in ML4 cells [68]. Finally, based on the metabolic model, it is argued that the trafficking defect in ML4 cells may be due to the secondary effect of gradual lipid accumulation [65]. However, since aberrant lipid trafficking in ML4 cells was rescued by over-expressed wild-type TRPML1 [40], the secondary effect is likely to be minimal.

TRPMLs in lysosomal iron release

In most mammalian cells iron is acquired through the endocytosis of Fe3+-bound transferrin receptors. Iron may also enter the endocytic pathways via autophagic ingestion of iron-binding proteins, for example, cytochrome C [69]. After reduction by an endolysosomal ferrireductase, Fe2+ is released from the endosome or lysosome into the cytoplasm via the Fe2+ permeable channels or transporter [69]. As mentioned above, ITRPML1 is permeable to both Ca2+ and Fe2+/Mn2+. Since TRPML1 is localized to the LEL, it has become a strong candidate as an endolysomal Fe2+ release channel [28]. In support of these data, some ML4 patients were reportedly associated with iron-deficiency and/or anemia [18].

Dong et al. has shown that TRPML1 can function as a Fe2+ permeable channel in the LEL based on patch-clamping LEL membranes [28]. Using iron imaging and staining methods, it was shown that ML4 fibroblasts exhibit a reduction of cytosolic Fe2+ levels and an increase of intralysosomal Fe2+ levels when compared to control cells [28]. The authors proposed that Fe2+ release from endosomes and lysosomes is specifically blocked due to a loss of function of TRPML1. Intralysosomal iron overload caused by a TRPML1-deficiency may lead to serious physiological consequences and could contribute to the neurodegeneration seen in ML4 patients (to be discussed below). Fe2+ permeability is not a general feature of all TRPML isoforms. TRPML2, but not TRPML3, is also permeable to Fe2+ (Dong et al., 2008), suggesting a cell type specific function for TRPML2. For example, TRPML2 is expressed on B and T lymphocytes [41,45] and iron metabolism is important for lymphocyte maturation and function [70].

The fact that TRPML1 plays dual roles in iron metabolism and lysosomal Ca2+ signaling may seem counterintuitive. However, since most TRPs are non-selective for cations, it is not surprising that many of them exhibit dual permeability to ions such as Na+ and Ca2+, each of which is involved with a distinct cellular output. When TRPs in somatosensory neurons are activated by sensory cues such as temperature, Na+ influx-mediated membrane depolarization is the major signal that mediates greater than 90% of the inward current [71]. Membrane depolarization leads to the propagation of an action potential along the axon that carries the information to the spinal cord and brain. Sensory activation of TRPs also results in small amounts of Ca2+ influx, that is sufficient to cause sensory adaption and/or peptide release from sensory neurons [15,71]. Although TRPML1 is permeable to both Fe2+ and Ca2+, TRPML1-defiency results in impaired Fe2+ homeostasis [28] but normal Ca2+ homeostasis [68]. The explanation for this difference may be the fact that the lysosomal Ca2+ gradient is dynamically maintained by the activity of the putative H+-Ca2+ exchanger while lysosomal Fe2+ is mainly controlled by the release pathway. In order to separate the effects of Ca2+ versus Fe2+, TRPML1 mutations that cause a selective disruption of individual permeability may prove insightful.

TRPMLs in neurodegeneration

The primary symptom of ML4 patients and TRPML1 KO mice is neurological despite the fact that TRPML-deficiency causes a clear cellular phenotype in all cell types [17,72]. Massive neuronal cell death and axonal degeneration are also seen in the brains of TRPML−/− flies [36]. Although glial cell death can also be detected in the fly brain, successful rescue of cell death by neuron-specific expression of TRPML suggests that non-neuronal cell death is secondary to neuronal death [36]. Neuronal cell death increases as an animal ages possibly because of an accumulation of toxic factors [36,72]. One potential factor is lipofuscin, which specifically accumulates in the brains of TRPML1 KO mice and TRPML−/− flies [36,72]. Lipofusin accumulates primarily in the lysosomes of TRPML−/− cells [36,72] and its production is likely to be a direct result of TRPML-deficiency. Indeed, the Ca2+ and Fe2+ permeability of TRPML1 is sufficient to explain lipofusin production in TRPML−/− cells. First, impaired Ca2+ release may result in trafficking defects and the delayed exit of lipids from the LEL compartment. This delayed exit suggests that TRPML2, TRPML3, or other lysosomal Ca2+ channels may compensate for the deficiency. Alternatively, less efficient trafficking pathways may exist in the cell. Regardless, this observed trafficking defect may still be tolerated by most ML4 cells since the primary symptom of ML4 patients is neurological defects despite the trafficking defect and enlarged LEL phenotype observed in all cell types [17]. Second, lysosomal Fe2+ overload associated with loss of TRPML1 may convert the accumulated lipids (due to a trafficking defect) into non-degradable lipofuscin under oxidative conditions through increase production of reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH•; Fenton reaction) [73]. In proliferating cells, lysosomal lipofuscin may not be toxic since it can be diluted during cell division [73]. However, in nonproliferative postmitotic cells such as neurons, accumulation of lipofuscin can result in cell death and neurodegeneration. It is hypothesized that correcting either the Ca2+ or Fe2+ defect may attenuate the symptoms of ML4 [69]. Therefore, lysosome-targeting iron chelators may be a useful therapy for ML4 [69].

Lipofuscin accumulation is often associated with disrupted autophagy, a lysosome-mediated degradation process that is impaired in many neurodegenerative diseases [74]. Lipofuscin is a non-degradable factor that may cause significant impairment of normal functions of lysosomes when in excess [73]. There are at least three basic functions of lysosomes: digestive and autophagic functions, signal transduction, and membrane trafficking. All of these functions can be inhibited by lipofuscin production. Indeed, impairment of autophagy has been reported in TRPML−/− cells [36,53,75] and TRPML1 interacts directly with the autophagic machineries [75]. In addition, overexpression of TRPMLs also results in an inhibition of autophagy [34,35]. Thus TRPMLs may have a direct role in autophagy that is independent of lipofuscin accumulation. Similarly, loss-of-function of TRPML1 affects membrane trafficking in a direct and indirect (lipofuscin-dependent) manner. Impaired autophagy appears to be a general feature of many lysosomal storage diseases [21]. Mitochondrial fragmentation is commonly seen in ML4 and other storage diseases since autophagy is required for recycling of damaged mitochondria [21,68]. Impaired mitochondrial function in turn causes oxidative stress [76]. During oxidative stress, TRPML1-deficiency causes intralysosomal Fe2+ overload and an increase in the production of free radicals and lipofuscin. Notably, intralysosomal Fe2+ concentration increases significantly during autophagic ingestion of mitochondria, which are known to contain abundant iron-binding proteins [73]. Therefore, one question to ask is how lipofuscin accumulation causes neurodegeneration. Since lipofuscin accumulation causes a significant impairment of membrane trafficking and autophagy, the subsequent effects of impaired autophagy, mitochondria fragmentation, oxidative stress, intralysosomal overload, and continued lipofuscin production may constitute a vicious cycle that leads to neuronal cell death and axonal degeneration. From a therapeutic point of view, breaking the cycle may protect neurons from degradation. For example, reducing oxidative stress by overexpressing HSP70 chaperone protein in neurons was able to break the cycle and attenuate neurodegeneration [36]. Along this line, correcting either the Ca2+ or Fe2+ defect might attenuate neurodegeneration and the neurological symptoms of ML4.

TRPML in other physiological functions

TRPMLs may also indirectly contribute to neurodegeneration. Recently, Venkatachalam et al. found that overexpression of Drosophila TRPML in non-neuronal cells was able to significantly reduce neuronal cell death [36]. Further analysis suggested that Drosophila TRPML is required for clearance of apoptotic neurons by glial and immune cells. It is not known whether mammalian TRPMLs have a similar function. However, considering the expression of all three TRPML proteins in lymphoid organs, it is possible that there is a general function for all TRPML members in immune cells. Since the reduction of oxidative stress in non-neuronal cells is ineffective in attenuating neurodegeneration [36], the mechanism by which TRPMLs are required for the functions of immune cells is probably different from those used in neurons. It is worth nothing that while there are three mammalian TRPML isoforms, C. elegans and Drosophila only express one single TRPML protein. C. elegans and Drosophila TRPML mutants appear to exhibit more severe symptoms than ML4 patients and TRPML1 KO mice [18,29,36,37]. Therefore, TRPML2 and TRPML3 may also participate in the non-neuronal functions such as those occurring in immune cells. Human TRPML2 has been shown to co-localize with major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) and CD59 antigen [44], whereas mouse TRPML1 has been shown to co-localize with MHC –II in macrophage cell lines [41]. Together, these data suggest that TRPMLs are possibly involved in immune cell development, differentiation, and antigen processing.

In addition to their putative involvement in neurodegeneration, TRPMLs may have other physiological functions as well. Although loss-of-function studies reveal a role of TRPMLs in neurodegeneration, their neuronal functions under physiological conditions are not clear. Neurite outgrowth is known to be dependent on lysosomal exocytosis [77], a process that involves TRPML1 activity [1,27]. In astrocytes, release of certain transmitters such as ATP is dependent on lysosomal exocytosis [78]. TRPML1 is also required for normal functions of secretory epithelial cells. For example, acid secretion from parietal cells is significantly reduced in ML4 patients [18]. Finally, although an abundance of data describe the intracellular functions of TRPMLs, the potential role of TRPMLs at the plasma membrane cannot be excluded. In specialized cells and/or under certain conditions, TRPMLs may be present and functional in the plasma membrane. This is especially true for TRPML3, which exhibits whole-cell currents when heterologously expressed in a variety of cell lines. The availability of TRPML2 and TRPML3 KO studies will help facilitate our understanding of their physiological functions.

Summary, Perspectives, and Future Directions

TRPMLs channels have been found to be localized to intracellular vesicles and interact with a variety of vesicular proteins. The basic channel pore properties of TRPMLs have been characterized, however the gating regulation is currently not known. Although functional studies suggest that TRPMLs play active roles in membrane fusion and fission, signal transduction, and vesicular homeostasis, the exact mechanisms of these functions have not been elucidated. In the future, we hope to see the advancement of our knowledge of TRPMLs in the following areas:

Identification of TRPML regulators and activators, which will help further characterize the roles of TRPMLs in signal transduction and/or membrane trafficking.

Development of specific antibodies to detect endogenous TRPMLs. With these research tools, a full knowledge of TRPML sub-cellular localization and tissue-expression pattern can be obtained.

With the development of TRPML2 and TRPML3 KO mice, more cell-type specific functions will be revealed for TRPML2 and TRPML3.

The use of real-time live imaging methods to capture TRPML-mediated juxtaorganellar Ca2+ transients. These seemingly “spontaneous” events may correlate with membrane fusion events that can be monitored with fluorescence imaging approaches.

Ion imaging methods will be applied to accurately measure luminal ion concentrations during both basal and stimulated states. This will provide basic information about the electric properties of endolysosomes and vesicles to better understand how TRPMLs function in these compartments.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to colleagues whose works are not cited due to space limitations. In many cases, review articles were referenced at the expense of original contributions. The work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by start-up funds to H.X. from the Department of MCDB and Biological Science Scholar Program, the University of Michigan, an NIH RO1 grant (NS062792 to H.X), pilot grants (to H.X.) from the UM Initiative on Rare Disease Research, Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIH grant P50-AG08671 to Gilman), and National Multiple Sclerosis Society. We appreciate the encouragement and helpful comments from other members of the Xu laboratory.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dong X, Wang X, Xu H. TRP channels of intracellualr membranes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelangeli F, Ogunbayo OA, Wootton LL. A plethora of interacting organellar Ca2+ stores. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christensen KA, Myers JT, Swanson JA. pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:599–607. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luzio JP, Bright NA, Pryor PR. The role of calcium and other ions in sorting and delivery in the late endocytic pathway. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1088–1091. doi: 10.1042/BST0351088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange I, Yamamoto S, Partida-Sanchez S, Mori Y, Fleig A, Penner R. TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra23. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calcraft PJ, et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay JC. Calcium: a fundamental regulator of intracellular membrane fusion? EMBO Rep. 2007;8:236–240. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martens S, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of membrane fusion: disparate players and common principles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:543–556. doi: 10.1038/nrm2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth MG. Phosphoinositides in constitutive membrane traffic. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:699–730. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luzio JP, Rous BA, Bright NA, Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Piper RC. Lysosome-endosome fusion and lysosome biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 9):1515–1524. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.9.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Bright NA, Gray SR, Luzio JP. The role of intraorganellar Ca(2+) in late endosome-lysosome heterotypic fusion and in the reformation of lysosomes from hybrid organelles. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1053–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, Peters JA. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:165–217. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slaugenhaupt SA. The molecular basis of mucolipidosis type IV. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:445–450. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altarescu G, et al. The neurogenetics of mucolipidosis type IV. Neurology. 2002;59:306–313. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun M, et al. Mucolipidosis type IV is caused by mutations in a gene encoding a novel transient receptor potential channel. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2471–2478. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.17.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Palma F, Belyantseva IA, Kim HJ, Vogt TF, Kachar B, Noben-Trauth K. Mutations in Mcoln3 associated with deafness and pigmentation defects in varitint-waddler (Va) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14994–14999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222425399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puertollano R, Kiselyov K. TRPMLs: in sickness and in health. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1245–F1254. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90522.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CS, Bach G, Pagano RE. Abnormal transport along the lysosomal pathway in mucolipidosis, type IV disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6373–6378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagata K, Zheng L, Madathany T, Castiglioni AJ, Bartles JR, Garcia-Anoveros J. The varitint-waddler (Va) deafness mutation in TRPML3 generates constitutive, inward rectifying currents and causes cell degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:353–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707963105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H, Delling M, Li L, Dong X, Clapham DE. Activating mutation in a mucolipin transient receptor potential channel leads to melanocyte loss in varitint waddler mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709096104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HJ, Li Q, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, So I, Kiselyov K, Muallem S. Gain-of-function mutation in TRPML3 causes the mouse Varitint-Waddler phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36138–36142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimm C, Cuajungco MP, van Aken AF, Schnee M, Jors S, Kros CJ, Ricci AJ, Heller S. A helix-breaking mutation in TRPML3 leads to constitutive activity underlying deafness in the varitint-waddler mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19583–19588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709846104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong XP, et al. Activating mutations of the TRPML1 channel revealed by proline scanning mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong XP, Cheng X, Mills E, Delling M, Wang F, Kurz T, Xu H. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature. 2008;455:992–996. doi: 10.1038/nature07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venugopal B, et al. Neurologic, gastric, and opthalmologic pathologies in a murine model of mucolipidosis type IV. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1070–1083. doi: 10.1086/521954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samie MA, Grimm C, Evans JA, Curcio-Morelli C, Heller S, Slaugenhaupt SA, Cuajungco MP. The tissue-specific expression of TRPML2 (MCOLN-2) gene is influenced by the presence of TRPML1. Pflugers Arch. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0716-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuajungco MP, Samie MA. The varitint-waddler mouse phenotypes and the TRPML3 ion channel mutation: cause and consequence. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Delling M, Li L, Dong X, Clapham DE. Activating mutation in a mucolipin transient receptor potential channel leads to melanocyte loss in varitint-waddler mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18321–18326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709096104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeevi DA, Frumkin A, Offen-Glasner V, Kogot-Levin A, Bach G. A potentially dynamic lysosomal role for the endogenous TRPML proteins. J Pathol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/path.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martina JA, Lelouvier B, Puertollano R. The calcium channel mucolipin-3 is a novel regulator of trafficking along the endosomal pathway. Traffic. 2009;10:1143–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HJ, Soyombo AA, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, So I, Muallem S. The Ca(2+) channel TRPML3 regulates membrane trafficking and autophagy. Traffic. 2009;10:1157–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkatachalam K, Long AA, Elsaesser R, Nikolaeva D, Broadie K, Montell C. Motor deficit in a Drosophila model of mucolipidosis type IV due to defective clearance of apoptotic cells. Cell. 2008;135:838–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treusch S, Knuth S, Slaugenhaupt SA, Goldin E, Grant BD, Fares H. Caenorhabditis elegans functional orthologue of human protein h-mucolipin-1 is required for lysosome biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4483–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiselyov K, Chen J, Rbaibi Y, Oberdick D, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, Shcheynikov N, Muallem S, Soyombo A. TRP-ML1 is a lysosomal monovalent cation channel that undergoes proteolytic cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43218–43223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LaPlante JM, Ye CP, Quinn SJ, Goldin E, Brown EM, Slaugenhaupt SA, Vassilev PM. Functional links between mucolipin-1 and Ca2+− dependent membrane trafficking in mucolipidosis IV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pryor PR, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Luzio JP. Mucolipin-1 is a lysosomal membrane protein required for intracellular lactosylceramide traffic. Traffic. 2006;7:1388–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson EG, Schaheen L, Dang H, Fares H. Lysosomal trafficking functions of mucolipin-1 in murine macrophages. BMC Cell Biol. 2007;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatachalam K, Hofmann T, Montell C. Lysosomal localization of TRPML3 depends on TRPML2 and the mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17517–17527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600807200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vergarajauregui S, Puertollano R. Two di-leucine motifs regulate trafficking of mucolipin-1 to lysosomes. Traffic. 2006;7:337–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karacsonyi C, Miguel AS, Puertollano R. Mucolipin-2 localizes to the Arf6-associated pathway and regulates recycling of GPI-APs. Traffic. 2007;8:1404–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song Y, Dayalu R, Matthews SA, Scharenberg AM. TRPML cation channels regulate the specialized lysosomal compartment of vertebrate B-lymphocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:1253–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HJ, Li Q, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, So I, Kiselyov K, Soyombo AA, Muallem S. A novel mode of TRPML3 regulation by extracytosolic pH absent in the varitint-waddler phenotype. Embo J. 2008;27:1197–1205. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung MK, Guler AD, Caterina MJ. TRPV1 shows dynamic ionic selectivity during agonist stimulation. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:555–564. doi: 10.1038/nn.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soyombo AA, Tjon-Kon-Sang S, Rbaibi Y, Bashllari E, Bisceglia J, Muallem S, Kiselyov K. TRP-ML1 regulates lysosomal pH and acidic lysosomal lipid hydrolytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7294–7301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bargal R, Bach G. Phospholipids accumulation in mucolipidosis IV cultured fibroblasts. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1988;11:144–150. doi: 10.1007/BF01799863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piper RC, Luzio JP. CUPpling calcium to lysosomal biogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sardiello M, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325:473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahluwalia JP, Topp JD, Weirather K, Zimmerman M, Stamnes M. A role for calcium in stabilizing transport vesicle coats. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34148–34155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vergarajauregui S, Connelly PS, Daniels MP, Puertollano R. Autophagic dysfunction in mucolipidosis type IV patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2723–2737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaPlantea Janice M, John Falardeaub MS, Daib Daisy, Browna Edward M, Slaugenhauptb Susan A, Vassilev Peter M. Lysosomal exocytosis is impaired in mucolipidosis type IV Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2006;89:339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.05.016. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peters C, Mayer A. Ca2+/calmodulin signals the completion of docking and triggers a late step of vacuole fusion. Nature. 1998;396:575–580. doi: 10.1038/25133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeevi DA, Frumkin A, Offen-Glasner V, Kogot-Levin A, Bach G. A potentially dynamic lysosomal role for the endogenous TRPML proteins. J Pathol. 2009;219:153–162. doi: 10.1002/path.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohacs T, Nilius B. Regulation of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels by phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch. 2007;455:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burgoyne RD, Clague MJ. Calcium and calmodulin in membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1641:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(03)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca(2+)-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell. 2001;106:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vergarajauregui S, Martina JA, Puertollano R. Identification of the penta-EF-hand protein ALG-2 as a CA2+−dependent interactor of mucolipin-1. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Churchill GC, Okada Y, Thomas JM, Genazzani AA, Patel S, Galione A. NAADP mobilizes Ca(2+) from reserve granules, lysosome-related organelles, in sea urchin eggs. Cell. 2002;111:703–708. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang F, Jin S, Yi F, Li PL. TRP-ML1 Functions as a Lysosomal NAADP-Sensitive Ca(2+) Release Channel in Coronary Arterial Myocytes. J Cell Mol Med. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang F, Li PL. Reconstitution and Characterization of a Nicotinic Acid Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NAADP)-sensitive Ca2+ Release Channel from Liver Lysosomes of Rats. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25259–25269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thai TL, Churchill GC, Arendshorst WJ. NAADP receptors mediate calcium signaling stimulated by endothelin-1 and norepinephrine in renal afferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F510–F516. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00116.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miedel MT, Rbaibi Y, Guerriero CJ, Colletti G, Weixel KM, Weisz OA, Kiselyov K. Membrane traffic and turnover in TRP-ML1-deficient cells: a revised model for mucolipidosis type IV pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1477–1490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang D, Zhao L, Clapham DE. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies Letm1 as a mitochondrial Ca2+/H+ antiporter. Science. 2009;326:144–147. doi: 10.1126/science.1175145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bach G, Chen CS, Pagano RE. Elevated lysosomal pH in Mucolipidosis type IV cells. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;280:173–179. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jennings JJ, Jr, Zhu JH, Rbaibi Y, Luo X, Chu CT, Kiselyov K. Mitochondrial aberrations in mucolipidosis Type IV. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39041–39050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mills E, Dong X, H F, Xu H. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowlus CL. The role of iron in T cell development and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:73–78. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(02)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Micsenyi MC, Dobrenis K, Stephney G, Pickel J, Vanier MT, Slaugenhaupt SA, Walkley SU. Neuropathology of the Mcoln1(−/−) knockout mouse model of mucolipidosis type IV. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:125–135. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181942cf0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kurz T, Terman A, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. Lysosomes in iron metabolism, ageing and apoptosis. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:389–406. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0394-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:931–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Venugopal B, Mesires NT, Kennedy JC, Curcio-Morelli C, Laplante JM, Dice JF, Slaugenhaupt SA. Chaperone-mediated autophagy is defective in mucolipidosis type IV. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:344–353. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kurz T, Terman A, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. Lysosomes and oxidative stress in aging and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arantes RM, Andrews NW. A role for synaptotagmin VII- regulated exocytosis of lysosomes in neurite outgrowth from primary sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4630–4637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0009-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Z, et al. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:945–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bargal R, et al. Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV. Nat Genet. 2000;26:118–123. doi: 10.1038/79095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bassi MT, Manzoni M, Monti E, Pizzo MT, Ballabio A, Borsani G. Cloning of the gene encoding a novel integral membrane protein, mucolipidin-and identification of the two major founder mutations causing mucolipidosis type IV. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1110–1120. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9297(07)62941-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fares H, Greenwald I. Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat Genet. 2001;28:64–68. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.LaPlante JM, Falardeau J, Sun M, Kanazirska M, Brown EM, Slaugenhaupt SA, Vassilev PM. Identification and characterization of the single channel function of human mucolipin-1 implicated in mucolipidosis type IV, a disorder affecting the lysosomal pathway. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Aken AF, Atiba-Davies M, Marcotti W, Goodyear RJ, Bryant JE, Richardson GP, Noben-Trauth K, Kros CJ. TRPML3 mutations cause impaired mechano-electrical transduction and depolarization by an inward-rectifier cation current in auditory hair cells of varitint-waddler mice. J Physiol. 2008;586:5403–5418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]