Abstract

Purpose

The safety and feasibility of posterior screw fixation of the cervical spine in children has not been well documented in the orthopedic literature. We performed a retrospective review of our experience using posterior cervical screw fixation in children.

Methods

The medical records and radiologic records of 36 children at a mean age of 10 years (range 3–16 years) were reviewed. Diagnoses included: ten instability, 11 deformity, seven trauma, five tumor, and three congenital abnormalities. Operative reports and postoperative computed tomography (CT) scans were reviewed to determine the technical feasibility of screw placement, any screw-related complications, and to assess for correct screw position. In this series, there were no neurologic complications, no vertebral artery injuries, and no screw-related complications.

Results

Thirty patients (141 screws) had screws evaluated postoperatively and were shown to be completely contained on postoperative CT scans. There were no revisions due to screw failure or dislodgement. There were no vascular or neurologic complications.

Conclusions

Posterior screw fixation in the pediatric population may be done safely and greatly enhances fixation strength for a variety of disorders requiring instrumentation and fusion.

Keywords: Pediatric, Cervical spine, Screw fixation

Introduction

The ability to obtain solid internal fixation for cervical spinal disorders enhances fusion rates and reduces the need for postoperative halo application with its potentially untoward consequences. Lateral mass fixation of the cervical spine has been popularized by Roy-Camille and others as a safe and efficacious method of obtaining solid cervical fixation [1]. The lateral mass is a quadrangular structure of bone that affords optimum purchase for screw fixation in a region of the spine not otherwise well suited for pedicle screw fixation in children. Adverse events related to screw malposition are usually due to the close proximity to exiting cervical nerve roots and the vertebral artery [2]. While the potential complications of a misplaced screw are high, in practice, many large series of adult patients have shown that this technique can be applied safely [1, 3–5].

Children present to the pediatric spine surgeon with a multitude of cervical spine problems, including: craniocervical instability, congenital malformations, post-laminectomy kyphosis, and a variety of other acquired or traumatic cervical disorders. Children have a high osteogenic potential. With that being said, rigid fixation of the pediatric spine enhances the ability to obtain a fusion and diminishes the need and/or length of postoperative immobilization. Previous reports on cervical fixation in children have focused on non-rigid techniques such as wire-rod configurations. The earliest reports on rigid fixation in children included the description of transarticular screws in cases of upper cervical spine instability [6]. We published the first report on modern cervical spine instrumentation in children with a noted high fusion rate and low complication rate [7]. Since that report, we have had continued success with posterior cervical screw–rod constructs and have expanded the application to younger children. This report focuses on our experience with posterior cervical screw fixation in children and the techniques used in order to facilitate safe screw placement in children.

Materials and methods

We reviewed the spinal database at Children’s Hospital Boston to find a cohort of patients who had undergone cervical spine instrumentation and fusion using a screw–rod construct between the years 2003 and 2007. Patients’ medical records were reviewed to determine diagnoses and demographic data. Operative reports were reviewed to determine the type of operation performed, as well as to determine any intraoperative complications or difficulties encountered with screw placement. Postoperative computed tomography (CT) scans were independently reviewed to determine the containment of screws or any malposition of screws. Postoperative radiographs and records were reviewed to determine the presence of any complications, as well as to document the clinical and radiologic status of the patient at follow-up.

Surgical technique

We have found it useful to obtain a CT scan on patients prior to the operation. In our experience, even in the youngest of patients, lateral mass anatomy is reliably present for screw fixation. In patients with congenital fusions, the CT scan can help assess the potential starting points and any associated anomalies which may preclude fixation at certain levels. Patients potentially undergoing fixation with C2 screws must have fine-cut CT scans to assess the position of the vertebral artery in relationship to the isthmus of the pars.

Patients are placed prone in the operating room either with a halo vest applied prior to turning with subsequent removal of the posterior vest for the operation or are positioned in a Mayfield headrest, which is firmly secured to the operating table. At our institution, motor and sensory evoked potentials as well as electromyography (EMG) scans are used in all cases. Standard midline incision and posterior element dissection is performed with exposure to the lateral border of the lateral mass. We use a modified Magerl technique for lateral mass screw placement [8–10]. The medial and lateral borders of the lateral mass are defined, as well as the superior and inferior borders, which correspond to the facet levels above and below. With this region now outlined as a rectangular box, the starting point is an area 1 mm inferior and 1 mm medial to the middle of the box. We make a small burr hole in order to see a cancellous blush of blood. This blush confirms a starting position, as well as making a stable divot for drill placement. We use a hand-powered drill which has a stop mechanism to prevent unwarranted drilling depth. We then aim our drill 30° laterally and 30° cephalad. We check a spot fluoroscopy view in the lateral plane in order to assure that our starting position is correct and that our orientation in the cephalad direction parallels the plane of the facet joint (Fig. 1). Some surgeons may chose to place lateral mass screws without fluoroscopy. With that being said, the small nature of the lateral mass in children affords little to no opportunity for screw rescue due to malposition. Therefore, we use fluoroscopy with screw placement, although its use is minimal. Once the starting point has been obtained, we use the stop drill bit, which is set corresponding to the size of the patients and ranges from 10 mm in small children to 14 mm in adolescents. Once we have drilled, we then probe the region to assure containment. In our experience, unicortical screws have afforded sufficient fixation, as has been shown in the literature. We tap our pilot screw hole followed by placement of a 3.5-mm polyaxial screw. Most screws are 10–14 mm in length; occasionally in a small child, we will use an 8-mm screw. It should be noted that most polyaxial screw heads are not placed completely flush to the bone, given the cephalad and lateral direction. Thus, if the pilot hole has been safely drilled and probed to 8 mm, then a 10-mm screw will be safely placed. Screw placement is also checked with a spot lateral fluoroscopic view to confirm the position. Once screws are placed, appropriate rod placement is performed, followed by decortications and autogenous graft placement. We recommend cross-link application to the rods if at all possible.

Fig. 1.

a Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of a 13-year-old male who sustained a three-column cervical spine injury while playing football. b Postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan confirming correct orientation of the lateral mass screws. c, d Postoperative radiographs documenting the restoration of alignment after circumferential fusion

Results

We identified 36 patients who fitted the criteria for this review. The mean age of the patients at the time of the operation was 11 years (range 3–16 years). The diagnosis included: ten non-traumatic instability, 11 deformity, seven trauma, five tumor, and three congenital abnormalities. Nine patients underwent an anterior procedure in addition to the posterior procedure. The reason for anterior surgery included: five patients with fractures requiring anterior column support, two tumor patients requiring anterior surgery, and two deformity patients requiring anterior support. A mean number of five levels were included in the fusion (range 2–7). The mean number of screws placed per patient was five (range 2–11). There were no intraoperative screw-related complications. The operative reports revealed three instances in which a lateral mass was felt to be inadequate for screw purchase after drilling and tapping: a 6-year-old with Down’s syndrome, a 5-year-old with Klippel-Feil syndrome, and a 4-year-old with post-laminectomy kyphosis. In all of these patients, screws were able to be placed at other levels. A retrospective analysis of preoperative CT scans in these patients revealed no clear reason for the inability to obtain purchase at the stated levels.

There were no postoperative neurologic abnormalities. The postoperative complications included: one acute infection, one sterile seroma requiring irrigation and debridement, and one broken rod with pseudarthrosis. The acute surgical site infection was in a patient who had post-laminectomy kyphosis and a history of radiation for spinal cord tumor. Her infection cleared with serial VAC dressing changes and intravenous antibiotics. She had a documented fusion by CT scan at 29 months follow-up. The patient with a seroma was a Down’s syndrome patient with basilar invagination and was noted to have persistent wound drainage, and was taken back to the operating room for wound irrigation and repeat closure 4 days after the index operation. He was culture-negative and developed no further complications, and fused uneventfully. The patient with a pseudarthrosis and broken rod has the diagnosis of Gorham’s disappearing bone disease. He presented at 29 months follow-up with a broken rod. He was revised via rod exchange and, subsequently, has undergone anterior surgery with grafting and instrumentation due to his tumor involvement.

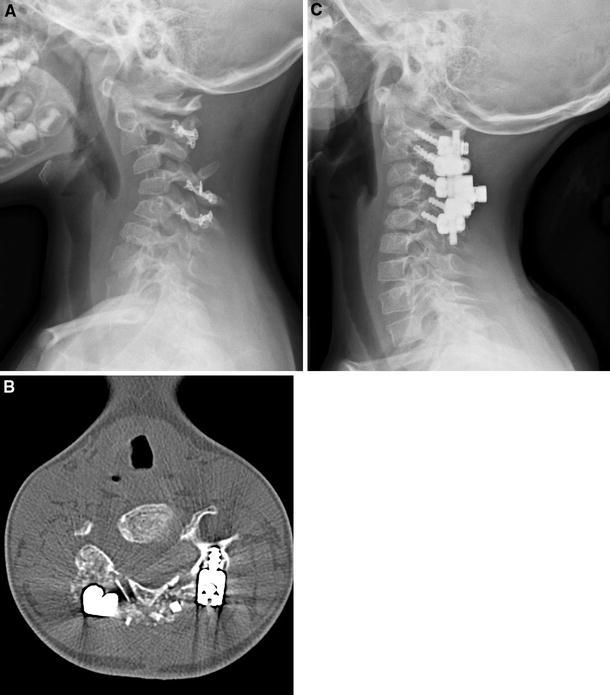

Thirty patients had postoperative CT scans available for review to include an evaluation of 141 screws. The axial, sagittal, and coronal cuts of the CT scans were evaluated and all screws were fully contained (Fig. 2). There were no malpositioned screws in this series. All patients had clinically obtained fusion with the exception of the Gorham’s patient. Fusion was deemed likely if there was no implant failure and there were no clinical problems related to the surgical site. The length of follow-up in this series was 23 months (range 12–36 months). No patient required revision of cervical instrumentation due to screw malposition, dislodgement, or breakage. There were no nerve root injuries, no spinal cord or vertebral artery injuries, and no cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks.

Fig. 2.

a Lateral radiograph of a 4-year-old patient who developed post-laminoplasty kyphosis after surgical treatment of a spinal cord arteriovenous malformation. b Postoperative CT scan documenting the containment of a lateral mass screw. c Postoperative lateral radiograph documenting improvement of her sagittal alignment following posterior instrumented fusion

Discussion

Our experience with posterior screw fixation of the cervical spine in children mirrors the success seen in the adult population [3], namely, our containment of screws into the lateral mass or pars was 100% via postoperative CT scanning. There were no neurologic complaints at long-term follow-up and there have been no screw revisions to date.

The lateral mass is a quadrangular area of bone which is readily definable both radiographically and clinically. Radiographically, we have found preoperative CT scanning to be a reliable method of determining the feasibility of screw fixation. In our series, no patient had lateral masses which precluded screw fixation. There were three instances in which the lateral mass could not be used for screw fixation, all of which were in young children. In the author’s opinion, this was likely due to having a sub-optimal starting point and not having the center of the quadrangular region of bone available for purchase of the screw. Asymmetry of drilling and tapping may have placed the screw path mostly against one side of the box, leading to a cortical wall and no resultant purchase of bone. In patients with congenital fusions requiring fixation, we have found that the CT scans help define the starting point(s) for screw fixation and help define which lateral masses have anatomy which is readily available for screw fixation. In our experience, CT scans are critical in cases requiring screw fixation in the pars, as the vertebral artery course is definable by CT scanning in relation to the isthmus of the pars of the axis.

CT is an excellent way to evaluate screw position postoperatively in these patients. Nearly all of our patients had postoperative CT scans via a pediatric protocol to minimize radiation. The sagittal, coronal, and axial cuts allow for the study of screw fixation. The containment of our screws was 100%. This to not surprising given the use of a modified Magerl technique coupled with spot lateral fluoroscopic views and meticulous probing of the screw path. The complete containment of all screws is important not only for rigid fixation, but also accounts for the absence of neurologic complications in our series, which has been reported at 1% in the adult literature. We also use a technique of unicortical screw fixation, as this has proven to be biomechanically sound for lateral mass screws and helps minimize the chance for inadvertent nerve or vertebral artery injury. We have not had any difficulty with screw fixation at C6 or C7 in the pediatric population and still prefer lateral mass screws over pedicle screws at these levels. Lateral mass screws also allow for stable cervical base fixation in patients with long constructs involving the cervicothoracic junction.

In our series of patients, some of the children underwent application of a halo for a period of time after the operation. It should be noted that fixation was solid in these patients and screw position was adequate. It is our belief that maintenance in a halo is a reasonable practice in younger children who may be less reliable. The length of time in a halo was not prohibitive and was likely shortened given the screw–rod constructs. As our experience increases in younger children, we still recommend halo application for a short period of time in order to maximize the chance for arthrodesis and to minimize an event such as a fall, which would possibly compromise fixation and arthrodesis.

Lateral mass fixation in the pediatric population is feasible and efficacious. Using a modified Magerl technique with meticulous probing along with intraoperative lateral fluoroscopy allowed for complete containment and accurate screw position in all patients. Screw fixation must be accompanied by neurologic monitoring, meticulous exposure, and abundant decortications and autologous graft in order to obtain arthrodesis. The clinical and radiologic outcome has been excellent in this series of pediatric patients. We recommend posterior screw fixation in children requiring arthrodesis for a cervical spine disorder.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Footnotes

This study was approved by the IRB at Children’s Hospital Boston.

References

- 1.Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Laville C, et al. Treatment of lower cervical spinal injuries—C3 to C7. Spine. 1992;17(10 Suppl):S442–S446. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199210001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu R, Haman SP, Ebraheim NA, et al. The anatomic relation of lateral mass screws to the spinal nerves. A comparison of the Magerl, Anderson, and An techniques. Spine. 1999;24(19):2057–2061. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekhon LH. Posterior cervical lateral mass screw fixation: analysis of 1026 consecutive screws in 143 patients. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(4):297–303. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000166640.23448.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swank ML, Sutterlin CE, 3rd, Bossons CR, et al. Rigid internal fixation with lateral mass plates in multilevel anterior and posterior reconstruction of the cervical spine. Spine. 1997;22(3):274–282. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deen HG, Birch BD, Wharen RE, et al. Lateral mass screw–rod fixation of the cervical spine: a prospective clinical series with 1-year follow-up. Spine J. 2003;3(6):489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockmeyer DL, York JE, Apfelbaum RI. Anatomical suitability of C1–2 transarticular screw placement in pediatric patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(Suppl 1):7–11. doi: 10.3171/spi.2000.92.1.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedequist D, Hresko T, Proctor M. Modern cervical spine instrumentation in children. Spine. 2008;33(4):379–383. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318163f9cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu R, Ebraheim NA, Klausner T, et al. Modified Magerl technique of lateral mass screw placement in the lower cervical spine: an anatomic study. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(3):237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris BM, Hilibrand AS, Nien YH, et al. A comparison of three screw types for unicortical fixation in the lateral mass of the cervical spine. Spine. 2001;26(22):2427–2431. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller JG, Carlson GD, Abitbol JJ, et al. Anatomic comparison of the Roy-Camille and Magerl techniques for screw placement in the lower cervical spine. Spine. 1991;16(10 Suppl):S552–S557. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199110001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]