Abstract

Fifty-six years after the introduction of Chiari’s pelvic osteotomy, we report the long-term function scores and radiographic grade of osteoarthritis in 66 patients with 80 pelvic osteotomies with a minimum followup time of 27 years (average, 32 years; range, 27–48 years). These 66 patients were those who could be contacted and who returned for a followup visit from among 450 patients operated between 1961 and 1981. Thirty-two hips (40%) in 28 patients had undergone a total joint arthroplasty after an average 26 years (range, 13–41 years). Forty-eight hips in 41 patients (60%) were not replaced, their Harris hip score being a median of 82 points (range, 37–100 points). For the 22 patients for whom we had complete radiographs the average preoperative CE angle was 11.6°, 48.6° (range, 31°–82.8°) immediately postoperatively, and 41.6° (range, 13.7°–90°) at last followup . Despite a functional hip score in most patients retaining their native hip, the degree of osteoarthritis progressed at last followup. We observed a similar mean age at the time of osteotomy in patients converted to total hip arthroplasty and those retaining their native hip. Age at time of surgery was inversely correlated (r = −0.78) with the interval between the osteotomy and THA. In this select patient group we found good functional outcome in patients who underwent Chiari pelvic osteotomy, with a conversion rate of 40% to total hip arthroplasty a mean of 32 years after the procedure.

Level of Evidence: Level IV, case series. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

In 1952 Karl Chiari performed the first pelvic osteotomy and waited 2 years before performing a second. After he judged this operation successful, he personally operated approximately 2000 patients from 1955 to 1982 (about 20 to 150 per year). There are 20 publications from the University Department of Orthopaedics on this subject [3, 4, 6–8] and Chiari himself wrote the first description in German in 1953 [3]. In 1974, he published the first article in English “Medial Displacement Osteotomy of the Pelvis” in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research [11]; there were several publications in German and French journals before and after this [3–10, 12–14].

After his death, his method was pursued in our department [1, 2, 27–30, 50], with perhaps the most important followup study reported by Windhager et al. in 1991 [50]. At that time the 20- to 34-year results of 242 selected pelvic osteotomies were reported of which 5% had complications. Over 50% had excellent or good results and only 18% were poor (using a system proposed by Tönnis [44, 45]. After Chiari’s death there was only one modification of the method: the patient was not immobilized in a plaster cast, but the pelvic osteotomy was fixed by two wires in the medial displacement position [50]. Articles are still being published about the Chiari osteotomy by various institutions [15–17, 20–25, 31–34, 36–40, 51], although since 1996 only single-digit Chiari pelvic osteotomies per year have been carried out at the University Department for Orthopaedics in Vienna. Surgical correction of dysplastic hip has become less frequent in part owing to ultrasound screening and early treatment of newborns. At the same time the number of other surgical techniques increased (polygonal pelvic osteotomy in adults [26], Salter pelvic osteotomy in children [41]). Further, patients with osteoarthritis are treated by total hip replacements at younger ages. Currently we limit the indication for a Chiari osteotomy to patients with high-grade dysplasia without signs of osteoarthritis.

More than 50 years after the development of this method, we decided to reexamine any patients we could reach. The purpose of the study was therefore to determine (1) how many and which patients had received total hip replacements at what interval; (2) their range of functional scores; and (3) the final correction of the CE angle and progression of OA (Tönnis).

Material and Methods

We identified all patients undergoing Chiari pelvic osteotomy at our institution since 1952 by screening the archived original charts of all patients admitted for surgery. The total number of patients identified was 1380 (1588 hips). From these we focused on a subgroup of all 450 patients with Chiari pelvic osteotomies performed between 1961 and 1981 and whose preoperative films were available in the archives; we attempted to contact all of these patients for followup. Based on the contact information from the patients’ charts we searched the hospital, healthcare provider, and public records for names of the patients and the current contact address. We were able to obtain contact data for 280 of the 450 patients (62%). Because of name or address changes it was not possible to locate the other 170 patients. The patients were contacted by mail or telephone and invited to our institution. Of the 280 patients, 18 had died, 29 were living in foreign countries, and the invitation letter was unanswered by 167 patients. Sixty-six of the 450 patients (15%) with 80 pelvic osteotomies returned to our institution for a followup examination. Of these, 57 were female and nine male. The preoperative diagnosis was hip dysplasia in 50 patients, dysplasia with subluxation of the femoral head in eight patients, congenital hip dislocation in five patients, coxa magna after Perthes disease in two patients, and osteoarthritis secondary to dysplasia in 15 patients. The minimum followup was 27 years (average, 32 years; range, 27–48 years) from the operation. The average age of the patients at the time of the index operation was 23 years (range, 2–50 years) and was 54 years (range, 31–78 years) at the time of the latest followup. Local ethics committee approval was obtained prior to the initiation of this study.

In the original method described by Chiari [4, 11] the patient was placed in a plaster cast in abduction for 3 weeks. Beginning in 1982 the position was held by two 2.2 mm Kirschner wires without immobilization [50].

Postoperatively the patients were mobilized with crutches without weight bearing for 3 weeks and then with weight bearing as tolerated for another 3 weeks.

Three of us (CC, JH, AL) performed the clinical evaluations. This consisted of a physical examination, calculation of the Harris hip score [19], and administration of a patient questionnaire requesting data on pain (visual analogue scale, 0–10 cm). Leg length discrepancy was measured clinically with the patient in a supine position using a measuring tape from the anterior superior iliac crest to the tip of the medial malleolus.

Pre- and postoperative radiographs were collected in the archives, scanned, and uploaded to the PACS system. A complete series of radiographs consisting of preoperative, postoperative, and followup images was available for 22 of 66 patients (33%). At followup, standardized anteroposterior standing radiographs of the pelvis, as well as anteroposterior and axial radiographs centered on the operated hip were performed with kV and mAs settings according to individual patient constitution, and a focus-to-film distance of 110 cm on a digital imaging system (Agfa Diagnostic Centre, Agfa-Gevaert, Belgium).

One of us (AL) graded the radiographs using the Tönnis grading system for osteoarthritis [47]. The center-edge angle of Wiberg was measured to identify and quantify acetabular dysplasia [35]. Medial displacement was defined as the extent of the medial shift of the distal fragment as a percentage of the width of the innominate bone at the level of osteotomy [36]. All measurements were made electronically, with use of magnified views and contrast control, where necessary (IMPAX, Agfa-Gevaert, Belgium).

We correlated the age at the time of Chiari PO with age at the time of conversion to THA using a nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient. One-way ANOVA using the Bonferroni post-hoc test was used to evaluate differences between the CE angles preoperatively, postoperatively, and at time of followup. Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism 4.0 (San Diego, CA) statistical software.

Results

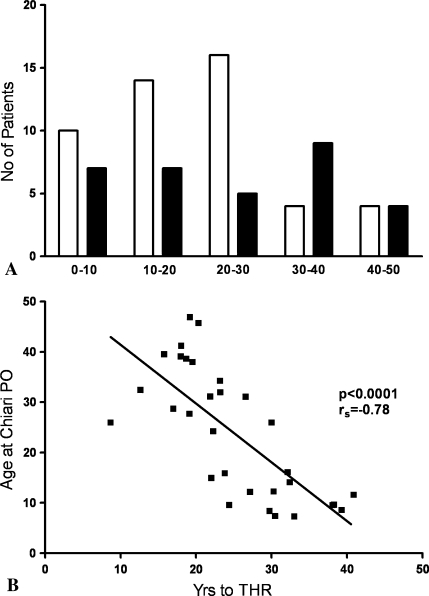

Thirty-two of the 80 hips (40%) had undergone a total joint arthroplasty. The average interval between the pelvic osteotomy and the hip arthroplasty was 26 years (range, 13–41 years). We found no difference in mean age at the time of Chiari PO between patients who had already had THR and the ones who have not. However, most patients who have not had THR were younger than 30 years old at time of Chiari PO, while the group who already received THR was more evenly distributed among age groups (Fig. 1A). Age at the time of surgery inversely correlated (r = −0.78, p < 0.001) with the interval between the osteotomy and THA (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1A–B.

(A) Age-distribution of our patient population at the time of Chiari PO, who already underwent THR (black) and who did not (white). (B) Correlation between the age at the time of Chiari PO and the time to THR. Patients who underwent Chiari PO early in their life had a longer interval until THR when compared to patients who underwent the procedure later in life.

Forty-eight of the 80 hips (60%) were not replaced. The median Harris hip score was 82 points (mean, 79 points; range, 37–100 points) (Table 1). The visual analogue scale for pain averaged 2.5 cm (range, 0–8.7 cm). The operated leg was, on average, 1.1 cm short (range, 0–8 cm). A limp was noted in 26 hips. Trendelenburg sign was positive in 11 hips.

Table 1.

Harris hip scores and range of movement at followup

| Mean | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Harris hip score subscales | ||

| Pain | 33 | 10–44 |

| Function | 37 | 3–47 |

| Deformity | 3 | 0–4 |

| Motion | 4 | 1–5 |

| Total | 79 | 37–100 |

| Range of movement | ||

| Flexion | 91° | 40–130° |

| Abduction | 37° | 10–70° |

| Adduction | 25° | 5–50° |

| External rotation | 25° | 0–50° |

| Internal rotation | 16° | 0–90° |

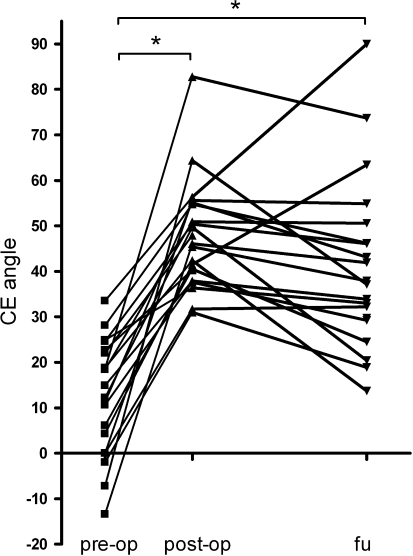

The average preoperative CE angle was 11.6° (range, −13° to 34°), the average postoperative CE angle was 48.6° (range, 31° to 82.8°), and the average CE angle at followup was 41.6° (range, 13.7° to 90°). We observed an improvement (p < 0.001) in the CE angle postoperatively which persisted at the time of followup. No change occurred between the postoperative CE angle and the CE angle at the time of followup (Fig. 2). The preoperative degree of osteoarthritis (Tönnis) was 0 in 10, 1 in 11, and 2 in one patient. At followup, the degree of osteoarthritis was 0 in one, 1 in one, 2 in seven, and 3 in 13 patients. The average medial displacement of the distal fragment was 49.3% (range, 22.9%–100%). We observed no correlation between the HHS at time of followup and the medialization achieved at the time of surgery.

Fig. 2.

The change in CE angle with time following Chiari PO is shown.

Discussion

Chiari’s pelvic osteotomy was developed 50 years ago at our institution. To have some sense of the long term outcomes, we determined (1) how many and which patients had received total hip replacements at what interval, (2) their range of functional scores and (3) the final correction of the CE angle and progression of OA (Tönnis).

Our study is limited by a number of factors. First, the total number of patients treated with Chiari’s osteotomy at our institution was higher than the actual 1380 patients identified by screening the charts because the charts from 1970 to 1975 were incomplete. Second, we were able to follow only a small percentage of the patients (15% of those whose records could be identified). Therefore, we cannot ensure the data are representative. Although in this selected group of patients age inversely correlated with the interval between the osteotomy and THA, the low number of patients is limiting. Nonetheless, we believe the data of value due to the long average followup period of 32 years.

The Chiari osteotomy was the first described operation for dysplasia with pelvic transection. Of the currently performed osteotomies developed later by Salter [41], Tönnis et al. [46], and Ganz et al. [18] there are comparable long-term data only for the Salter osteotomy (Table 2). In a recent publication, the results of children operated between the ages of 1.5 and 5 years were published after 40 to 48 years [43, 49]. At a mean of 45 years, 54% of surviving hips had an average CE angle of 40°. At 30 years in this same cohort, 99% of the hips had no reoperation, a higher percentage than with the Chiari osteotomy. However, as the average age at surgery with the Chiari osteotomy was 23 years, a comparison is not possible because a similar followup time results in most patients in the Chiari group being approximately 20 years older (and in their fifth or sixth decades). It is more feasible to compare the osteotomy with the 51 Tönnis osteotomy cases, although such followup period has been reported only to an average of 15 years [48]. Of these, 88% still had preserved their hips and 64% had excellent results. The severity of the dysplasia was comparable to that in our patients (CE angle 9° compared to 11° in the Chiari osteotomy) but the severity of the osteoarthritis was not comparable to ours as 41 of their cases had Grade 0, 10 had Grade 1, and none were Grade 2. In our patients Grades 0 and 1 were equally distributed and there was also one case of Grade 2; thus our patients tended to have worse osteoarthritis [48]. It is difficult to compare survival of the Chiari osteotomy with the Ganz osteotomy, as this was developed later and the only long-term data arise from 63 patients followed 19 to 23 years [42]. In that series of patients with the Ganz osteotomy 60% survived without hip arthroplasty after an average of 20 years, while in a report of the Chiari osteotomy 91% of the patients survived after an average of 24.8 years [50]. The CE angle of 6° was comparable in both studies.

Table 2.

Literature overview on longterm results of pelvic osteotomies

| Study | PO type | Hips | Mean followup | Survival | CE angle | Osteoarthritis grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al. [43] | Salter | 80 | 45 years | 54%* | 40° | Kellgren 0 or 1 57% |

| Kellgren 2 14% | ||||||

| Kellgren 3 or 4 29% | ||||||

| Van Hellemondt et al. [48] | Tönnis | 51 | 15 years | 88%** | 28° | Tönnis 0 57% |

| Tönnis 1 41% | ||||||

| Tönnis 2 2% | ||||||

| Steppacher et al. [42] | Ganz | 68 | 20 years | 60.5%* | 34° | Mean Tönnis 1.1±1 |

| Windhager et al. [50] | Chiari | 236 | 25 years | 91%** | Not evaluated | Tönnis 0 6.8% |

| Tönnis 1 40.5% | ||||||

| Tönnis 2 34.7% | ||||||

| Tönnis 3 18% | ||||||

| Kotz et al. (current study) | Chiari | 80 | 32 years | 60%** | 42° | Tönnis 0 4.5% |

| Tönnis 1 4.5% | ||||||

| Tönnis 2 32% | ||||||

| Tönnis 3 59% |

*Kaplan Meier analysis.

**Preservation rate at followup.

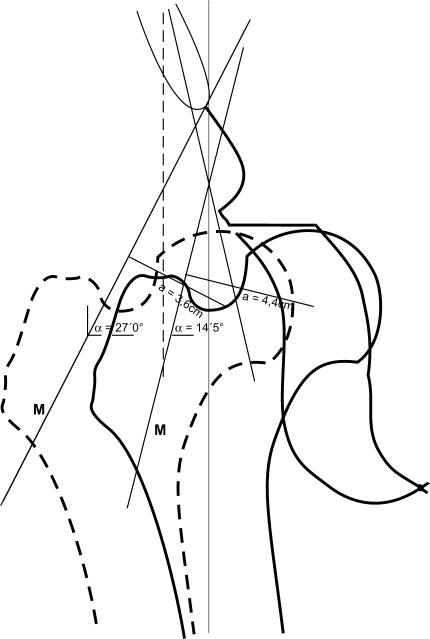

The Chiari osteotomy is often criticized for forming a substitute acetabulum with the hip capsule. We believe the biologic disadvantage of a secondary acetabulum is outweighed by a positive effect due to the biomechanical advantage of medialization with a shortening of the hip’s load arm (Fig. 3), so that despite progressive osteoarthritic changes our findings in this selected group of patients were judged satisfactory even after several decades (Fig. 4). However, further studies on a larger number of patients are required to confirm the long-term outcome of this procedure.

Fig. 3.

Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis distributes the load over a more extensive surface area in a large socket, while at the same time reducing the load by changing the leverage.

Fig. 4A–B.

(A) Preoperative radiograph of a 25 year old female patient with bilateral hip dysplasia. (B) The radiograph shows a 44-year result after bilateral Chiari osteotomies. The heads are fully covered. Despite narrowing of the joint space the patient is pain-free and shows a good functional result.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heidrun Hofmann, Lena Hirtler, Barbara Lifka, and Stefan Pucher for collecting the patients’ data and radiographs from the archives and Joanna Wagner for helping with the preparation of the manuscript. We thank the AFOR Stiftung (Selzach, Switzerland) for supporting this study with a research stipend.

Footnotes

One author (CC) received financial support by a research stipend of the AFOR (Association for Orthopaedic Research) foundation.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Böhler N, Chiari K, Grundschober F, Niebauer G, Plenk H., Jr Guidelines for Chiari’s osteotomy in the immature skeleton developed from a canine model. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;192:299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böhler N, Chiari K, Kristen H. Radiolucent spatulas for simplifying Chiari’s surgical technic of pelvic osteotomy [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1983;121:159. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1051332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiari K. Pelvic osteotomy in hip arthroplasty [in German] Wien Med Wochenschr. 1953;103:707–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiari K. Results of pelvic osteotomy as of the shelf method acetabular roof plastic [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1955;87:14–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiari K. Operative treatment of the hip joint in congenital hip joint dislocation [in German] Wien Med Wochenschr. 1957;107:1020–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiari K. Pelvic osteotomy in plastic surgery of the acetabular roof [in German] Langenbecks Arch Klin Chir Ver Dtsch Z Chir. 1959;292:856–857. doi: 10.1007/BF02449840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiari K. Operative therapy of coxarthrosis [in German] Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1964;76:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiari K. Pelvic osteotomy in the treatment of coxarthrosis [in German] Beitr Orthop Traumatol. 1968;15:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiari K. Pelvis osteotomy in the treatment of coxarthroses [in German] Acta Orthop Belg. 1971;37:509–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiari K. Proceedings: Late results following pelvic osteotomy–prevention of pre-arthrosis [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1974;112:603–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiari K. Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974:55–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Chiari K. History and present indications for corrective surgery of the acetabulum in hip dysplasia (author’s transl) [in German] Arch Orthop Unfallchir. 1976;86:67–76. doi: 10.1007/BF00415304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiari K, Drexler H, Hofer H. Diagnosis of hip joint dysplasia in general practice [in German] Landarzt. 1965;41:223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiari K, Endler M, Hackel H. Indications and results of osteotomy of the pelvis using Chiari’s method in advanced arthrosis [in German] Acta Orthop Belg. 1978;44:176–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debnath UK, Guha AR, Karlakki S, Varghese J, Evans GA. Combined femoral and Chiari osteotomies for reconstruction of the painful subluxation or dislocation of the hip in cerebral palsy. A long-term outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1373–1378. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B10.17742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong HC, Lu W, Li YH, Leong JC. Chiari osteotomy and shelf augmentation in the treatment of hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:740–744. doi: 10.1097/00004694-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagala J, Blacha J, Bednarek A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy in the treatment of hip dysplasia in adults [in German] Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2006;71:183–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman S, Jaklic A, Iglic A, Kralj-Iglic V. Hip stress reduction after Chiari osteotomy. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2002;40:369–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02345067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herman S, Kralj-Iglic V, Iglic A, Antolic V. Biomechanical analysis of Chiari osteotomy. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2002;7:365–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosny GA, Fabry G. Chiari osteotomy in children and young adults. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10:37–42. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito H, Matsuno T, Minami A. Comparison of the surgical approaches for a Chiari pelvic osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:204–208. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B2.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito H, Matsuno T, Minami A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy for advanced osteoarthritis in patients with hip dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1439–1445. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito H, Matsuno T, Minami A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy for advanced osteoarthritis in patients with hip dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(Suppl 1):213–225. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotz R, Da Vid T, Helwig U, Uyka D, Wanivenhaus A, Windhager R. Polygonal triple osteotomy of the pelvis. A correction for dysplastic hip joints. Int Orthop. 1992;16:311–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00189612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotz R, Slancar P. Pelvic osteotomy and delivery (author’s transl) [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1973;111:797–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotz R, Wagenbichler P. Influence of a Chiari pelvic osteotomy on subsequent labor and delivery [in German] Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1973;33:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lack W, Feldner-Busztin H, Ritschl P, Ramach W. The results of surgical treatment for Perthes’ disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lack W, Windhager R, Kutschera HP, Engel A. Chiari pelvic osteotomy for osteoarthritis secondary to hip dysplasia. Indications and long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:229–234. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macnicol MF, Lo HK, Yong KF. Pelvic remodelling after the Chiari osteotomy. A long-term review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:648–654. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B5.14653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellerowicz HH, Matussek J, Baum C. Long-term results of Salter and Chiari hip osteotomies in developmental hip dysplasia. A survey of over 10 years follow-up with a new hip evaluation score. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1998;117:222–227. doi: 10.1007/s004020050233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;418:81–86. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakano S, Nishisyo T, Hamada D, Kosaka H, Yukata K, Oba K, Kawasaki Y, Miyoshi H, Egawa H, Kinoshita I, Yasui N. Treatment of dysplastic osteoarthritis with labral tear by Chiari pelvic osteotomy: outcomes after more than 10 years follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelitz M, Guenther KP, Gunkel S, Puhl W. Reliability of radiological measurements in the assessment of hip dysplasia in adults. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:331–334. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.856.10474491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohashi H, Hirohashi K, Yamano Y. Factors influencing the outcome of Chiari pelvic osteotomy: a long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:517–525. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B4.9583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osebold WR, Lester EL, Watson P. Observations on the development of the acetabulum following Chiari osteotomy. Iowa Orthop J. 2002;22:66–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piontek T, Szulc A, Glowacki M, Ciemniewska K. Computer tomography evaluation of the hip joint after Chiari osteotomy. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2006;8:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piontek T, Szulc A, Glowacki M, Strzyzewski W. Distant outcomes of the Chiari osteotomy 30 years follow up evaluation. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2006;8:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy RR, Morin C. Chiari osteotomy in Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:1–9. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salter RB. Role of innominate osteotomy in the treatment of congenital dislocation and subluxation of the hip in the older child. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1966;48:1413–1439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steppacher SD, Tannast M, Ganz R, Siebenrock KA. Mean 20-year followup of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1633–1644. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0242-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas SR, Wedge JH, Salter RB. Outcome at forty-five years after open reduction and innominate osteotomy for late-presenting developmental dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2341–2350. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tönnis D. General radiography of the hip joint. In: Tonnis D, editor. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip in Children and Adults. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 100–142. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tönnis D. Clinical and radiographic schemes of evaluating therapeutic results. In: Tönnis D, editor. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip in Children and Adults. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tönnis D, Behrens K, Tscharani F. A new technique of triple osteotomy for turning dysplastic acetabula in adolescents and adults (trans) [in German] Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1981;119:253–265. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1051453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tönnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1747–1770. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hellemondt GG, Sonneveld H, Schreuder MH, Kooijman MA, Kleuver M. Triple osteotomy of the pelvis for acetabular dysplasia: results at a mean follow-up of 15 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:911–915. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wedge JH, Thomas SR, Salter RB. Outcome at forty-five years after open reduction and innominate osteotomy for late-presenting developmental dislocation of the hip. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 2 Pt 2):238–253. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Windhager R, Pongracz N, Schonecker W, Kotz R. Chiari osteotomy for congenital dislocation and subluxation of the hip. Results after 20 to 34 years follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:890–895. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B6.1955430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanagimoto S, Hotta H, Izumida R, Sakamaki T. Long-term results of Chiari pelvic osteotomy in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip: indications for Chiari pelvic osteotomy according to disease stage and femoral head shape. J Orthop Sci. 2005;10:557–563. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]