Abstract

Background

Acute care physical therapists contribute to the complex process of patient discharge planning. As physical therapists are experts at evaluating functional abilities and are able to incorporate various other factors relevant to discharge planning, it was expected that physical therapists’ recommendations of patient discharge location would be both accurate and appropriate.

Objective

This study determined how often the therapists’ recommendations for patient discharge location and services were implemented, representing the accuracy of the recommendations. The impact of unimplemented recommendations on readmission rate was examined, reflecting the appropriateness of the recommendations.

Design

This retrospective study included the discharge recommendations of 40 acute care physical therapists for 762 patients in a large academic medical center. The frequency of mismatch between the physical therapist's recommendation and the patient's actual discharge location and services was calculated. The mismatch variable had 3 levels: match, mismatch with services lacking, or mismatch with different services. Regression analysis was used to test whether mismatch status, patient age, length of admission, or discharge location predicted patient readmittance.

Results

Overall, physical therapists’ discharge recommendations were implemented 83% of the time. Patients were 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted when the therapist's discharge recommendation was not implemented and recommended follow-up services were lacking (mismatch with services lacking) compared with patients with a match.

Limitations

This study was limited to one facility. Limited information about the patients was collected, and data on patient readmission to other facilities were not collected.

Conclusions

This study supports the role of physical therapists in discharge planning in the acute care setting. Physical therapists demonstrated the ability to make accurate and appropriate discharge recommendations for patients who are acutely ill.

Discharge planning is the development of a discharge plan for follow-up services for a patient prior to leaving the hospital, with the aim of containing costs and improving patient outcomes.1 Discharge planning is a complex process, and many health care disciplines may contribute to the plan, including formal discharge planning coordinators, nurses, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and physicians. Reviews of discharge planning processes showed that they consistently involve the assessment of many factors, including cognitive, physical and social/financial status, environmental concerns, and access to formal and informal care.2,3

In an effort to assess these many factors, formal discharge planning in the United States often is practiced as a collaborative, multidisciplinary effort led by a case manager, particularly for patients identified as having an increased risk for poor outcomes.4,5 Although the shift toward collaborative discharge planning has improved patient outcomes, there remains room for further improvement. A study by Mamon and colleagues6 showed that multidisciplinary discharge planning efforts led by formal case managers appeared to be significantly more effective in arranging home nursing care and rehabilitation services than informal discharge planning; however, patients still often reported these and other needs were unmet after discharge. The study did not examine how the discharge planning process failed to accurately identify or meet the needs of the patients, but as many health care professionals participate in the multifactorial process, the final decision on discharge placement may not take into consideration each professional's recommendation. Important information from one discipline may be overlooked or excluded from the final discharge plan, leading to failure of the plan.

Poor discharge planning and the failure to provide necessary services may have an impact at several levels: failure of the patient to reach optimal health and functional status, increased cost to the hospital and decreased resource availability to others due to increased length of stay and readmission, or possible adverse events or conditions causing harm to the patient.7 In an effort to better understand failure of the plan, several factors have been associated with poor postdischarge outcomes: aged 80 years and older; inadequate support system; multiple, active, chronic health problems; history of depression; moderate to severe functional impairment; multiple hospitalizations during the prior 6 months; hospitalization within the past 30 days; fair or poor self-rating of health; or history of nonadherence to the therapeutic regimen.7

It is clear from the large number and broad nature of factors associated with poor discharge outcomes that discharge planning is a complex process requiring the assessment and assimilation of multiple factors. Additional evidence of discharge planning as a complex process is the lack of use of standardized quantitative measures to determine discharge recommendations. Despite the validation of measures such as the Berg Balance Scale to predict discharge disposition,8 physical therapists and hospitals do not rely solely on standardized tests in regard to discharge planning.9,10 Standardized screening forms are often used to identify patients at high risk of poor outcomes in order to initiate the formal multidisciplinary discharge planning process, but they are not used to make the decision on discharge location and services.3,5,6,11

The need for comprehensive assessment of functional status is one factor in discharge planning that is directly related to the practice of physical therapy. One study quantified change in functional status, reporting that 35% of patients aged 70 years and older showed a decline in activities of daily living function between hospital admission and discharge.12 Patients experiencing a decline in functional status while in the hospital may no longer be able to function adequately in the environment they lived in prior to admission, and are less likely to recover baseline function and health status.13 There is an association between decreased functional status and transfers to and from acute care settings.14 There also is an association between decreased functional status and complicated posthospital care transitions.15

The studies described above show that level of functional ability is related to discharge location; however, other studies demonstrate that the relationship, consistent with the theme of discharge planning, is complex. Although patients returning home had a higher level of function than those who were discharged elsewhere, some patients who were significantly impaired returned home with family support. Patients who had family support but were discharged to facilities were the most impaired.8 Additionally, researchers studying the effect of functional level on length of hospital admission found that patients with a higher level of function demonstrated a shorter length of stay than average, but patients with a low level of function who were discharged to a supportive environment also had a shorter-than-average length of stay.16 These findings highlight the complex relationship between functional ability and discharge needs and further support physical therapist evaluation of functional abilities, assistance required for safety, and recommendations for discharge location based on what the patient requires and what is available to them.

Physical therapists in the acute care setting play an important role in the multidisciplinary discharge planning process. “Discharge to the appropriate level of care” often is a goal in acute care physical therapy,17 and therapists routinely make recommendations regarding discharge placement and any continuing therapy services for patients. Due to short average lengths of admission in acute care, patients often need continued physical therapy services after leaving acute care, and therapists may recommend that continued services take place in the home, a skilled nursing facility (SNF), a rehabilitation center, or an outpatient setting.18

Although creating a discharge plan is a multidisciplinary process, physical therapists practicing in acute care are in a unique position to assess the discharge needs of a patient. This is well described within the scope of practice in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice: “The plan of care identifies anticipated goals and expected outcomes, taking into consideration the expectations of the patient/client and appropriate others…. The plan of care includes the anticipated discharge plans. In consultation with appropriate individuals, the physical therapist plans for discharge and provides for appropriate follow-up or referral.”19(p46) Furthermore, physical therapists are health care professionals who diagnose and treat individuals of all ages who have medical problems or other health-related conditions that limit their ability to move and perform functional activities in their daily lives,19 and the assessment of functional abilities is a particularly important and complex aspect in determining discharge needs.

Having established that physical therapists are well qualified to participate in the complex discharge planning process, how do they come to a decision on a discharge recommendation? According to a qualitative study by Jette et al,9 physical therapists appeared to use a patient's level of functioning and disability as the core dimension in their initial decision-making process. In general, they were guided by 4 constructs when making a discharge recommendation: patients’ functioning and disability, patients’ wants and needs, patients’ ability to participate in care, and patients’ life context. The therapists gathered and integrated information from multiple constructs before making their discharge recommendation, showing consideration of what the patients required and what was available in their environment.9

Building upon previous descriptions of the complexities of the decision-making process and the idea that physical therapists are uniquely suited to contribute useful insight through their evaluation and assessment skills, we wanted to validate the participation of acute care physical therapists in the discharge planning process. Because we hypothesized that therapists are able to successfully incorporate all of the various factors involved in the discharge planning process and that there is value placed on the therapist's recommendation by the final discharge plan decision maker, we anticipated that the therapist's discharge recommendations for patients in the acute care setting would match the patient's actual discharge location and services a majority of the time. Furthermore, supporting the idea that therapists are appropriate in their recommendations, we expected an increased likelihood of hospital readmissions when recommendations were not implemented.

Method

The University of Michigan Hospital is a 700-bed acute care teaching hospital. Our facility is a level 1 trauma center offering and receiving helicopter transfers for patients from Michigan and its surrounding states who are in critical and complex situations; many of our patients are transferred from outside hospitals for ongoing care.

Discharge Planning Process

The discharge planning process in our facility occurs in a fairly, but not completely, standardized manner. The initial parts of the process are standard; practice management coordinators use a screening form based on the factors associated with poor discharge outcomes to screen all admitted patients and identify those who are at increased risk for poor discharge outcomes. Patients who are not identified as high risk by the screening process have discharge planning done by their staff nurse, unless formal discharge planning is later requested. For patients who are identified as high risk, formal discharge planning is initiated, with practice management coordinators taking the lead role in the discharge planning process. They read the documentation on discharge recommendations from the physical therapist evaluation and any subsequent physical therapist documentation and incorporate it into a multidisciplinary discharge planning process, including any documentation they read from the medical/surgical team, unit nurses, and, when consulted, occupational therapists and social workers. In this basic process, the coordinator may or may not seek additional information from other members of the health care team. If a consensus has been identified, the coordinator proceeds to arrange insurance benefits and necessary services. If there is not a consensus, the coordinator will elicit additional information from the other members of the health care team, usually using the hospital alphanumeric paging and telephone systems. A lack of consensus can occur, for example, if the patient's preferences change or if insurance benefits are not available.

Physical therapist involvement in the discharge planning process starts when the medical/surgical team sends an electronic consult to the Division of Physical Therapy through our online medical charting system. The therapist does an initial evaluation, with the exact procedures varying according to the ability of the patient to participate. The overall process is best described in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice:

[Physical therapists] engage in an examination process that includes taking the patient/client history, conducting a systems review, and performing tests and measures to identify potential and existing problems. To establish diagnoses, prognoses, and plans of care, physical therapists perform evaluations, synthesizing the examination data and determining whether the problems to be addressed are within the scope of physical therapist practice. Based on their judgments about diagnoses and prognoses and based on patient/client goals, physical therapists provide interventions (the interactions and procedures used in managing and instructing patients/clients), conduct reexaminations, modify interventions as necessary to achieve anticipated goals and expected outcomes, and develop and implement discharge plans.19(p21)

The physical therapist documents his or her evaluation in the computerized patient medical record. At the top of every therapist evaluation and any subsequent documentation, information is highlighted that is particularly relevant to discharge recommendations, specifically therapist recommendations for discharge location, the amount of assistance required for patient safety, necessary assistive devices, and the need for ongoing physical therapy and the appropriate setting. This information is consistently provided by therapists, regardless of whether or not patients are receiving formal discharge planning. Follow-up physical therapy treatments are provided as appropriate throughout the patient's acute care stay, and discharge recommendations are updated and documented each time a therapist works with the patient.

Although all physical therapist recommendations are consistently documented in the medical record in a standard manner, the remaining discharge process varies in how communication is exchanged. Beyond the basic discharge planning process, some service areas of the hospital follow additional procedures that increase in-person communication between health care providers. Three of the services hold additional daily or weekly “discharge rounds” interdisciplinary meetings, attended by the resident physician, practice management coordinator, occupational therapist, physical therapist, and social worker. In addition, some coordinators work with 1 or 2 specific services and make it a point to meet in person with the therapists, whereas other coordinators float among services and do not do so.

Data Collection

To conduct our retrospective study of the outcomes of the discharge planning process, we obtained University of Michigan Privacy Board approval for waiver of informed consent to access patient medical records and institutional review board approval for the use of physical therapists as human participants. We accessed the medical records of all patients who received a physical therapist evaluation during our study period. We also collected data about career history from consenting therapists to further describe therapist practice at our facility.

We created a secure database and separated identifying information about patients and therapists from de-identified, coded data collection forms. We selected one week (Sunday–Saturday) in each season of the preceding year. The weeks were in December 2007 and March, June, and September 2008 and did not include any holidays.

Two research assistants were trained, using case studies, to access medical records and find the relevant information and enter it into the database. Information was collected primarily from physical therapist evaluations and treatment notes, physician discharge notes, and practice management coordinator evaluations and notes. Occasionally, data were found in emergency department documentation, physician admitting history and physical documents, social work notes, nursing notes, and outpatient or rehabilitation facility documentation from our health system. Any questions related to data collection were resolved by consensus of the 3 primary investigators (B.A.S., C.J.F, and N.F.).

Variables and Inclusion Criteria

We identified 51 physical therapists who were working in acute care during our selected weeks. Forty out of the possible 51 therapists consented to participate in our study. The 11 therapists who were not included were those we could not contact, who were no longer employed at the university, or who were temporary staff who did not evaluate patients during the 4 weeks we analyzed. One of the 3 primary investigators discussed the study with each therapist before the informed consent form was signed. After consent, participating therapists were asked to provide the following background information: total months of practice as an acute care physical therapist, total months and setting of other, nonacute care physical therapist experience, and total months of practice as an acute care physical therapist at University of Michigan Hospital.

We used hospital billing records to identify that 780 patients received a physical therapist evaluation during our specified 4 one-week periods, and we included all of them in our study. We specified the following operational definitions and collected the following data from patient medical records:

Age of patient, in years.

Patient's primary service at discharge—service team of attending physician at the time of discharge, listed by abbreviation code.

Date of admission, in MM/DD/YYYY format.

Date of discharge, in MM/DD/YYYY format.

Date of physical therapy evaluation, in MM/DD/YYYY format.

Discharge location—the physical location the patient was sent to at the end of the hospital admission, coded as home without physical therapy, home with outpatient therapy, home with home therapist, subacute rehabilitation/SNF, acute rehabilitation, extended care facility without therapy, or expired.

Physical therapist at discharge—physical therapist identifier code of the therapist who documented the final discharge recommendation.

Physical therapist discharge recommendation—the discharge location and services that were determined by the therapist as necessary to promote patient safety and any recovery, as based on the patient's current level of function and available resources at discharge, coded as home without physical therapy, home with outpatient therapy, home with home therapist, subacute rehabilitation/SNF, acute rehabilitation, or extended care facility without therapy.

Match—when the actual discharge location and services were the same as the discharge recommendation in the final therapist documentation.

- Mismatch—when the actual discharge location or services were not the same as the discharge recommendation in the final therapist documentation.

- ∘ Mismatch with services lacking—the patient did not receive follow-up services when a home therapist was recommended.

- ∘ Mismatch with different services than recommended or extra services—the patient received home physical therapy instead of recommended outpatient therapy or the patient received home therapy when no follow-up therapy was recommended.

- Reason for mismatch, categorized as:

- ∘ Patient refusal of placement—the therapist recommended placement or services, and the patient or his or her legal representative declined,

- ∘ Insurance issues—the therapist recommended placement or services, and the patient did not receive them due to lack of insurance or insurance denial of services,

- ∘ Medical complexity of the patient precludes placement—the patient is on a ventilator or receiving enteral/parental feedings, for example, or

- ∘ Other—any other reason.

Readmission—if the patient was admitted to our acute care facility within 30 days of discharge, a time period consistent with similar studies.11,20

Data Analysis

We used Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Office 2007)* for database formation and SPSS software (versions 16.0 and 17.0)† for statistical analyses. We used descriptive statistics to summarize physical therapist and patient characteristics. We calculated the frequency of occurrence of patient discharge locations, mismatch, and readmission. Patients who expired were included in demographic and descriptive data but excluded from statistical analyses of mismatches or readmission. We used a general linear modeling technique, explained below, to determine which variables were associated with an increased risk of readmission. An alpha level of .05 was used for all hypothesis testing.

We did logistic regression analysis using generalized estimating equations to control for correlation of the outcomes by physical therapy and to predict the probability that a patient would be readmitted. The predictor variables we included in the model were mismatch status, patient age, length of admission, and discharge location. These are all of the variables we collected that could have had an effect on readmission. Patient age and length of admission were collapsed from continuous variables into categories to allow for more meaningful analysis. Age was categorized as ≤35 years, 36 to 55 years, 56 to 70 years, 71 to 84 years, and ≥85 years. Length of admission was categorized as less than 2 days, 2 to 4 days, 5 to 7 days, 8 to 10 days, 11 to 14 days, and ≥15 days. Mismatch status and discharge location were categorized as previously defined.

We used this analytic approach rather than the more common method of linear regression for 2 reasons. First, our response variable (readmission) is a dichotomous outcome. Second, it allowed us to control for the fact that each physical therapist made discharge recommendations for multiple patients and outcomes for a given therapist were not independent.21,22 Preliminary models tested for correlation of outcomes by physical therapy, but the observed correlation was not significant. The reported results specified an independent correlation structure.

Results

Patient Demographics

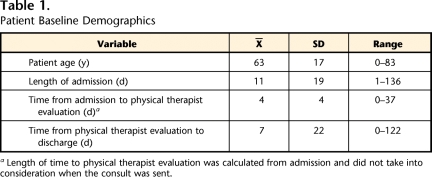

Of the 780 patients we identified as having received physical therapist evaluations in the specified 4 weeks, we successfully collected data from the medical records of 762 patients. Eighteen patients were excluded because their discharge location or the therapist recommendation could not be determined. This situation occurred when information was missing from the medical record or clerical errors led to an inability to locate the patient's medical record. Of the 762 patients from whom we collected data, 743 were eventually discharged from acute care, and 19 expired. Patients tended to be older adults who were distributed across medical (48%), surgical (27%), neurology (7%) and trauma/orthopedic (18%) services. Although the ranges were broad, the patients had an average hospital admission of 11 days and were evaluated by a physical therapist around day 4 of their admission (Tab. 1). The discharge locations of the patients from whom we collected data were as follows: home without physical therapy (44%), home with home therapy (26%), subacute rehabilitation/SNF (19%), acute rehabilitation (5.5%), expired (2.5%), home with outpatient therapy (2%), and extended care facility without therapy (1%).

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Demographics

a Length of time to physical therapist evaluation was calculated from admission and did not take into consideration when the consult was sent.

Mismatches

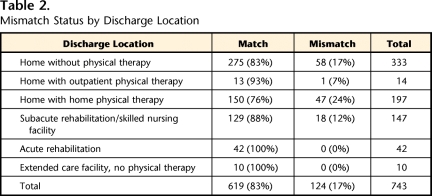

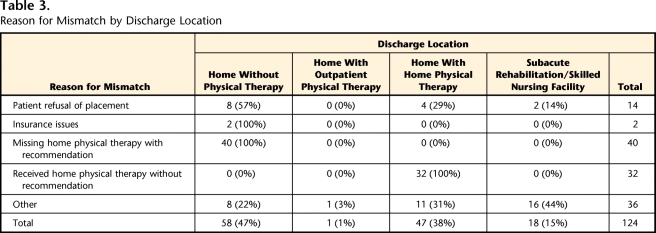

There was a mismatch between physical therapist recommendation and patient discharge location in 124 of 743 cases, or 17% of the time. The breakdown by service groups was: neurology/neurosurgery, 21%; medicine, 19%; surgery, 16%; and trauma/orthopedics, 7%. Mismatches are categorized by discharge location in Table 2 and by reason for mismatch in Table 3. The majority of mismatches occurred in patients who were discharged home. The most frequent reason for mismatch was patients who did not receive home therapy when recommended. The second largest group of mismatches were patients who received home therapy services that were not recommended, a condition that reflects unnecessary use of resources. Patient refusal of placement or services was the third largest category, and lack of insurance or insurance denial of services caused very few mismatches.

Table 2.

Mismatch Status by Discharge Location

Table 3.

Reason for Mismatch by Discharge Location

Although most mismatches occurred in patients who were ultimately discharged home, mismatches in the “other” category of reasons for mismatch did include patients who were subsequently discharged to a subacute rehabilitation facility or SNF. These cases were scenarios where no beds were available at the recommended level of care in the patient's preferred geographical area or where patients were denied admittance to an acute rehabilitation facility despite the recommendation.

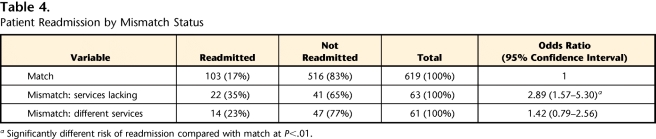

Readmission

As shown in Table 4, 139 patients (approximately 18% of our sample) were readmitted to our hospital within 30 days of their discharge. Our overall readmission rate is consistent with that of other studies.20,23 In our logistic regression analysis to predict the probability that a patient would be readmitted, mismatch status, discharge location, and length of admission were significant predictor variables. Patient age was not a significant predictor variable.

Table 4.

Patient Readmission by Mismatch Status

a Significantly different risk of readmission compared with match at P<.01.

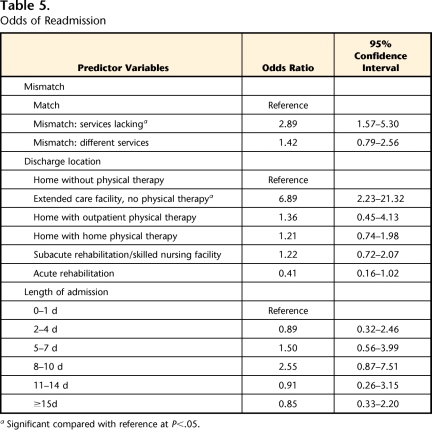

Table 5 shows the results of follow-up hypothesis testing. Holding all other variables constant, a patient was 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted when the therapist discharge recommendation was not implemented and services were lacking compared with patients with a match (mismatch with services lacking versus match, odds ratio [OR]=2.89, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.57–5.30). Patients whose therapist discharge recommendations were not implemented and who received different services or extra services were not significantly more likely to be readmitted than patients with a match (mismatch with different services versus match, OR=1.42, 95% CI=0.79–2.56).

Table 5.

Odds of Readmission

a Significant compared with reference at P<.05.

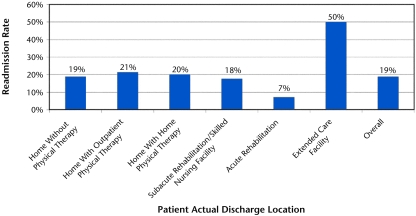

Follow-up testing also revealed that patients discharged to an extended care facility were 6.9 times more likely to be readmitted (OR=6.89, 95% CI=2.23–21.32) as compared to patients discharged home without therapy. The results for patients discharged to an acute rehabilitation setting approached significance in the direction of lower risk of readmission (OR=0.41, 95% CI=0.16–1.02) as compared to patients discharged home without therapy. In Figure 1 we show the different readmission rates by discharge location.

Figure.

Rate of readmission by discharge location. Overall readmission rate was 18%, and patients discharged to extended care facilities without physical therapy were significantly more likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days.

Physical Therapists

The 40 therapists included in the sample had a mean of 110 months of total experience as a practicing physical therapist (range=3−354 months). As 23 of the physical therapists had career experience beyond the acute care setting, the range of acute care experience was the same; however, the mean was lower (mean of 57.5 months of acute care experience).

Discussion

Overall, patients were discharged in accordance with the physical therapist discharge recommendation 83% of the time. When the discharge recommendation was not implemented and recommended follow-up services were not received, patients were 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted to our hospital within 30 days of discharge. Together, these results indicate that therapists are able to integrate multiple factors contributing to the discharge needs of the patient to make accurate and appropriate discharge recommendations.

An overall match rate of 83% between the therapist discharge recommendation and the patient's actual discharge location and services indicates therapists are able to successfully incorporate all of the various factors involved in the discharge planning process. This finding indicates that there is value placed on the therapist recommendation by the final discharge plan decision maker. It is possible, however, that in some cases the discharge recommendation happened to match the patient's actual discharge location without actually influencing the decision making of the nurse or practice management coordinator making the final decision. It is difficult for us to explain the patients who did not receive home physical therapy when recommended or the patients who received home therapy services that were not recommended—by far the largest causes of a mismatch. Either situation is a poor outcome, as it leads to a patient lacking in necessary services or unnecessary use of limited resources. These cases ultimately reflect a lack of communication between the physical therapist and the practice management coordinator, even though the therapist recommendations were clearly documented in the electronic medical record.

In the case of patients not receiving home physical therapy that was recommended, it is possible that the therapist documentation was not completed before the discharge plan was in place and no verbal exchange about the recommendation took place, or that the practice management coordinator did not value the information. Alternatively, it is possible that the patient was not receiving formal discharge planning and, despite the therapist identifying the patient's need for services, no one followed up to set up home therapy services. Interestingly, Mamon et al6 reported a similar finding that 43% of patients over the age of 60 years who were discharged home reported that they had an unmet need for physical therapy or rehabilitation services. Although physical therapist recommendations were not reported in their study, the findings indicate that there seem to be a number of patients being discharged with unmet needs. Perhaps practice management coordinators need to screen patients for formal discharge planning needs at discharge or after discharge, not just at admission. Patients lacking necessary follow-up services are a problem that needs to be addressed, as our findings show that when physical therapist discharge recommendations were not implemented and recommended follow-up services were not received, patients were 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted to our hospital.

As the United States struggles to balance efficiency and quality of health care, the ability of physical therapists to provide accurate and appropriate discharge recommendations becomes even more important. Discharge planning is increasingly becoming part of an integrated package of health care, and even small reductions in readmission rates could free up capacity for subsequent admissions in a health care system where there is a shortage of acute hospital beds.1 Decreases in readmission rates, appropriate allocation of resources, and avoidance of unnecessary services can help contain escalating health care costs.

Another aspect of containing health care costs relates to the employment of physical therapists in the acute care setting. Since the initiation of the Medicare prospective payment system and its use of diagnosis-related groups, payments to hospitals have been determined based on the patient's diagnosis, regardless of whether the patient receives services such as physical therapy. Acute care physical therapists have the challenge of justifying their salary cost to the hospital as outweighed by the benefit to the patient and the hospital. This challenge is difficult for a number of reasons. Therapists often are consulted to work with the patients who are more medically and functionally compromised—patients who are more likely to have negative outcomes than their less compromised peers. In addition, therapists often are advocating for additional services for patients, such as discharge to a rehabilitation facility, and the patient's length of stay often increases as he or she waits for admission to another facility. These findings demonstrate that therapists benefit both the patient and the hospital through their crucial role in the discharge planning process. When therapist discharge recommendations were implemented and recommended follow-up services were received, the patient and the hospital had an increased likelihood of positive outcomes through a decreased risk of readmission.

In addition to whether or not the therapist recommendation was implemented, risk of readmission also was partially predicted by the patient's actual discharge location. Patients discharged to an extended care facility without physical therapy were 6.9 times more likely to be readmitted, whereas patients discharged to acute rehabilitation approached a significantly lower risk of 0.4 times as likely to be readmitted. This finding probably reflects the nature of illness and reason for admission of these patients, and possibly reflects the quality of follow-up care they receive. Patients usually are discharged to an extended care facility without a recommendation for continued physical therapy because they are very ill with a poor prognosis for functional gains, whereas patients are discharged to an acute rehabilitation setting because it is believed that they will tolerate and benefit from at least 3 hours per day of interdisciplinary rehabilitation. Acute rehabilitation patients also continue to receive 24-hour nursing care and the other benefits (and drawbacks) of a hospital setting, whereas patients discharged home do not. Patients discharged to subacute rehabilitation or an SNF also receive 24-hour nursing care and daily rehabilitation, but, for a variety of reasons, have not been admitted to acute rehabilitation or discharged home. Further speculation on the relationship between discharge location and risk for readmission is beyond the scope and design of our study.

Of further interest, although we acknowledge this information is specific to our facility, the frequency of mismatch was not evenly distributed across the different primary attending services that discharged the patients. Some services had a higher rate of mismatch than others. The rate was highest for neurology/neurosurgery and lowest for trauma/orthopedics. One contributing factor may be the nature of admissions; the orthopedic surgeons perform a high volume of planned surgeries compared with the trauma/orthopedics and neurology/neurosurgery services, which have a lesser volume of patients and larger proportion of unplanned admissions. Planned admissions allow patients adequate time to confirm insurance benefits and consider discharge needs ahead of time.

Different frequency of mismatch also is likely related to the culture of each service and differential value placed on the physical therapist recommendation, as well as the slightly different processes by which communication is exchanged (eg, the presence or absence of formal interdisciplinary meetings). Within our 4 weeks of representative data, evaluations provided by each physical therapist were distributed across the different services, avoiding undue influence of this phenomenon on our final results but still reflecting the service-specific rates of mismatch.

Limitations and Further Questions

The major limitation of our study is that it is unique to our facility and may have limited generalizability to other acute care settings. The large size of our hospital leads to many staff members in each discipline, each of whom practices in an individual manner within the community of their discipline and within the larger hospital community. Resident physicians and physical therapists rotate between service areas of the hospital, interacting with different members of the health care team and providing care to different types of patients within each area. As an academic medical center and level 1 trauma center, the facility tends to care for patients who are more severely ill and complex, which certainly influences discharge locations and readmission rates.

In addition to the facility-specific aspects of our study, other limitations were that we collected limited information on the patients who received physical therapist evaluations. We did not address readmission of patients to hospitals other than our own and we did not assess the reason for readmission. We did not collect information on reason for admission, severity of illness, comorbidities, or functional level of the patients, which is information that would allow us to understand more about patterns of recommendation for discharge location or rates of readmission. In a cognizant effort to respect patient privacy, we did not collect information on patient sex, race, or ethnicity, as we felt a discussion of how these variables might relate to discharge location and readmission rates was beyond the scope of our report.

In regard to tracking readmission only to our own hospital, our readmission rate reflects only readmission to our hospital and is likely lower than an overall readmission rate, as there are almost certainly patients discharged from our facility who were readmitted to facilities closer to their home. Although our readmission rate needs to be interpreted in context, the proportion of mismatches should be accurate. Patients who were part of a mismatch should have been equally likely to be readmitted to our hospital compared with an outside hospital. By not assessing the reason for readmission, we may have included patients who were readmitted for purely medical, and not functional, reasons. Overall, readmission for any reason reflects a failure of the discharge plan, which may have been avoided with proper supportive postdischarge care. A decline in physical function is known to contribute to emergency department visits in older adults.24

Future research, with a larger sample size, could investigate how clinical experience influences the accuracy of discharge recommendations of acute care physical therapists. We also think it would be interesting to follow up with patients and gather their perception of their recovery and functional status in relation to their discharge services and location. We are particularly interested in the patients who were functioning at a level where both subacute rehabilitiation/SNF and home with home physical therapy were viable options. In addition, we were not able to address how frequency of acute care physical therapist treatments influences discharge locations, which may be of particular relevance in these “borderline” situations.

Conclusions

Overall, our data strongly support the role of physical therapists in discharge planning in acute care. Physical therapists demonstrated the ability to make accurate discharge recommendations for patients with complex clinical presentations who are acutely ill; these patients were discharged in accordance with the therapist discharge recommendation 83% of the time. More important, we showed that the therapist discharge recommendations were appropriate, as patients were 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted when the discharge recommendations were not implemented and recommended follow-up services were lacking.

The Bottom Line

What do we already know about this topic?

Acute care discharge planning is a complex process that involves clinicians from varied disciplines and the assessment of many factors. Physical therapists often are involved in discharge planning and make recommendations for follow-up services, but the accuracy and appropriateness of their recommendations have not been studied.

What new information does this study offer?

This study indicates that physical therapists are able to integrate multiple patient factors to make accurate and appropriate discharge recommendations. When the physical therapist's recommendation was not implemented and follow-up services were lacking, patients were more likely to be readmitted to the hospital.

If you’re a patient, what might these findings mean for you?

If you are in the hospital and have any concern that you will not be fully functional at discharge, you should seek a physical therapist's recommendation for the most appropriate discharge destination.

Footnotes

All authors provided concept/idea/research design, writing, data collection, and consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). Dr Smith and Ms Fields provided data analysis. Dr Smith provided project management. Ms Fields provided participants. Dr Smith and Ms Fernandez provided clerical support.

The authors thank the physical therapy staff at the University of Michigan Hospital for their participation and support, particularly Casandra Redmon and Lauren Lobert for data collection. They also thank Diane Jette, PT, DSc, for her comments on the initial idea.

A poster presentation of this research was given at the Combined Sections Meeting of the American Physical Therapy Association; February 17–20, 2010; San Diego, California.

This publication was made possible with support from the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute; grant UL1 RR024140 01 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Dr Smith is supported by a National Institute of Aging Institutional Training Grant to Jeri Janowsky (principal investigator). During her PhD studies, she was supported by grant H424C010067 from the US Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services to Dale Ulrich (principal investigator).

Microsoft Corp, One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052-6399.

SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, Chicago, IL 60606.

References

- 1.Shepperd S, Parkes J, McClaran JJ, Phillips C. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;3:CD000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson MF. Discharge planning: issues and challenges for gerontological nursing: a critique of the literature. J Adv Nurs 1994;19:492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddock KS. Characteristics of effective discharge planning programs for the frail elderly. J Gerontol Nurs 1991;17:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickey ML, Cook EF, Rossi LP, et al. Effect of case managers with a general medical patient population. J Eval Clin Pract 2000;6:23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamon J, Steinwachs DM, Fahey M, et al. Impact of hospital discharge planning on meeting patient needs after returning home. Health Serv Res 1992;27:155–175 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowles KH, Naylor MD, Foust JB. Patient characteristics at hospital discharge and a comparison of home care referral decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wee JY, Wong H, Palepu A. Validation of the Berg Balance Scale as a predictor of length of stay and discharge destination in stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:731–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jette DU, Grover L, Keck CP. A qualitative study of clinical decision making in recommending discharge placement from the acute care setting. Phys Ther 2003;83:224–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potthoff S, Kane RL, Franco SJ. Improving hospital discharge planning for elderly patients. Health Care Financ Rev 1997;19:47–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddock KS. Collaborative discharge planning: nursing and social services. Clin Nurse Spec 1994;8:248–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. The combined effects of baseline vulnerability and acute hospital events on the development of functional dependence among community-living older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54:M377–M383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd C, Landefeld CS, Counsell S, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2171–2179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman EA, Min SJ, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Posthospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1449–1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ensberg MD, Paletta MJ, Galecki AT, et al. Identifying elderly patients for early discharge after hospitalization for hip fracture. J Gerontol 1993;48:M187–M195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jette DU, Brown R, Collette N, et al. Physical therapists’ management of patients in the acute care setting: an observational study. Phys Ther 2009;89:1158–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curtis KA, Martin T. Perceptions of acute care physical therapy practice: issues for physical therapist preparation. Phys Ther 1993;73:581–594; discussion 594–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. 2nd ed.Phys Ther 2001;81:9–746 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einstadter D, Cebul RD, Franta PR. Effect of a nurse case manager on postdischarge follow-up. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:684–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of Biostatistics Florence, KY: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnik L, Liu D, Hart DL, Mor V. Benchmarking physical therapy clinic performance: Statistical methods to enhance internal validity when using observational data. Phys Ther 2008;88:1078–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowles KH, Ratcliffe SJ, Holmes JH, et al. Post-acute referral decisions made by multidisciplinary experts compared to hospital clinicians and the patients’ 12-week outcomes. Med Care 2008;46:158–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW. Does functional decline prompt emergency department visits and admission in older patients? Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:680–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]