Abstract

T cell activation required for host defense against infection is an intricately regulated and precisely controlled process. Although in vitro studies indicate three distinct stimulatory signals are required for T cell activation, the precise contribution of each signal in regulating T cell proliferation and differentiation after in vivo infection is unknown. In this study, altered peptide ligands (APLs) derived from the protective Salmonella-specific FliC antigen and CD4+ T cells specific for the immune-dominant FliC431–439 peptide within this antigen were used to determine how changes in TCR stimulation impact CD4+ T cell proliferation, differentiation, and protective potency. To explore the prevalence and potential use of altered TCR stimulation by bacterial pathogens, naturally-occurring APLs containing single amino acid substitutions in putative TCR contact residues within the FliC431–439 peptide were identified and used for stimulation under both non-infection and infection conditions. Based on this analysis, naturally-occurring APLs that prime proliferation of FliC-specific CD4+ T cells either more potently or less potently compared with the wild-type FliC431–439 peptide were identified. Remarkably, despite these differences in proliferation, all APLs primed reduced IFN-γ production by FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells after stimulation in vivo. Moreover, after expression of the parental FliC431–439 peptide or each APL in recombinant Listeria monocytogenes, only CD4+ T cells stimulated with the wild-type FliC431–439 peptide conferred significant protection against challenge with virulent Salmonella. These results reveal important and unanticipated roles for TCR stimulation in controlling pathogen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation, differentiation, and protective potency.

INTRODUCTION

Three distinct, yet inter-related, stimulatory signals are required for the activation and differentiation of naïve T cells into cytokine-producing effector T cells (1, 2). Although naïve T cells likely receive these stimulation signals concurrently during contact with antigen-presenting cells in a coordinated fashion, each signal has also been shown to individually control unique facets in T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation. For example, antigen specificity controlled by T cell receptor (TCR) signaling dictates which subset of T cells becomes initially activated (3, 4), while costimulation signals primarily mediated by CD28 signaling prevent these newly activated T cells from becoming anergic (5, 6). In this regard, a growing list of specific cytokines that includes IL-6, IL-12, IL-21, type I IFNs, and TGF-β have each been demonstrated to provide additional stimulation signals that controls the expansion, survival, and differentiation program of newly activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (7–15). Therefore, coordinated stimulation through the TCR, costimulation receptors, and specific cytokine receptors each has the potential to play unique and defined roles required for synchronized T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation.

Although there is ample evidence supporting the ability of specific cytokines to control CD4+ T cell differentiation into each distinct T-helper lineage, other T cell stimulation signals have also been implicated to play important roles in this process. Altered peptide ligands (APLs) containing amino acid substitutions in TCR contact residues from defined MHC class II peptide antigens have been used to characterize how TCR stimulation can also control the CD4+ T cell differentiation regardless and independent of exogenous cytokines. For example, stimulation of CD4+ T cells from TCR transgenic mice specific for an I-Ab restricted peptide within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85B (Ag85B) with wild-type Ag85B244–252 peptide primes robust IFN-γ with minimal IL-4 production, while stimulation with a peptide variant containing a single glycine to alanine substitution within the TCR contact residue at position 248 abolishes IFN-γ production and is replaced by reciprocal IL-4 production (16). In agreement with these results where T cells are stimulated in vitro, stimulation with APLs can also have profound effects on CD4+ T cell differentiation in vivo. For example, CD4+ T cell IFN-γ production that normally occurs after “immunization” with the human collagen IV protein is abolished and replaced by IL-4 production when a peptide variant containing a single amino acid substitution within a defined TCR contact residue is used instead (17). Recently, the impact of TCR stimulation has also been extended to play important roles in controlling the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response after in vivo infection. Using recombinant Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) that express either the parental H-2Kb OVA257–264 peptide or defined APLs derived from this peptide, TCR stimulation was found to dictate the kinetics of CD8+ T cell contraction and migration within lymphoid organs (18). Interestingly, despite these differences, OVA257–264-specific CD8+ T cells were activated and formed functional memory cells similarly regardless of differences in TCR stimulation (18). Taken together, these results indicate differences in TCR stimulation may control critical and unanticipated features in T cell differentiation and the antigen-specific T cell response during infection.

In this study, we sought to explore how differences in TCR stimulation may impact proliferation, differentiation, and protective potency for pathogen-specific CD4+ T cells. Given the importance and protective effects of CD4+ T cells in host defense against Salmonella typhimurium, a defined MHC class II peptide that spans amino acids 431–439 within the protective FliC antigen of Salmonella was utilized in this study (19–24). This FliC431–439 peptide is presented to CD4+ T cells by the murine MHC class II molecule, I-Ab, since CD4+ T cells from FliC-specific TCR transgenic mice derived from C57BL/6 mice expand in an antigen-specific manner after adoptive transfer into syngeneic recipient mice (21, 25). Furthermore, given the highly conserved nature of FliC and other flagellin components among diverse bacterial species, we examined the prevalence and explored the potential use of altered TCR stimulation for CD4+ T cells specific to this antigen by other bacteria. This lead to the identification of four naturally-occurring APLs containing single amino acid substitutions in putative TCR contact residues within the FliC431–439 peptide. When compared with the parental FliC431–439 peptide, naturally-occurring APLs that prime proliferation of FliC-specific CD4+ T cells either more or less potently were identified. Remarkably, despite these differences in proliferation, each APL compared with the parental FliC peptide primed reduced IFN-γ production in vivo and conferred diminished protection against subsequent challenge with virulent Salmonella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 (I-Ab) mice were purchased from The National Cancer Institute and used between 6–8 weeks of age. FliC431–439-specific (SM1) CD4+ TCR transgenic mice were intercrossed with CD45.1+ mice and maintained on a Rag-1-deficient background as described (25). All mice were housed within University of Minnesota specific pathogen-free facilities and experiments were conducted under institutional IACUC approved protocols.

Peptides

The parental I-Ab-restricted wild-type FliC431–439 peptide, and each APL derived from this peptide were purchased from United Biochemical Research (≥ 90% purity; Seattle, WA): RFNSAITNLGN (WT FliC), RFNSAITNIGN (FliCL438I), RFDSAITNLGN (FliCN432D), RFESAITNLGN (FliCN432E), and RFNFAITNLGN (FliCS433F). The I-Ab-restricted Ag85B244–252 peptide (AYNAAGGHNAV) was used as an irrelevant stimulation control. All peptides were dissolved in DMSO (100 mM), and further diluted in sterile saline to the indicated concentration used for in vitro stimulation. For in vivo stimulation, 50 μg each peptide was diluted with saline (200 μL) and intravenously injected into mice.

T cell stimulation

For in vitro stimulation, splenocytes from SM1 TCR transgenic mice were cultured in 96-well round-bottom plates (1 × 106 cells/mL) containing the indicated concentration of each peptide in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM Sodium pyruvate, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% nonessential amino acids, and penicillin (100 U/mL) + streptomycin (100 U/mL). For some experiments, CD4+ T cells from SM1 TCR transgenic mice were labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) prior to stimulation using standard labeling conditions (5 μM for 10 minutes at room temperature). For adoptive transfer, 2 × 104 CD4+ T cells from SM1 TCR transgenic mice were intravenously inoculated into recipient mice one day prior to peptide inoculation or recombinant Lm infection. Antibodies and other reagents for cell surface, intracellular, or intranuclear staining were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For measuring cytokine production by cells stimulated in vitro, brefeldin A was added to cultures for the final 5 hours prior to intracellular cytokine staining. For measuring cytokine production by CD4+ T cells ex vivo, splenocytes were stimulated with WT FliC431–439 peptide or each FliC-derived APL in the presence of brefeldin A for 5 hours prior to intracellular cytokine staining.

Bacteria

Lm ΔActA strain DPL-1942 along with methods for Lm transformation has been described previously (26–28). Briefly, recombinant Lm expressing either the parental wild-type FliC431–439 peptide or each APL derived from this peptide were generated by cloning the coding sequence for each into the “open” pAM401-based expression construct that allows transcription behind the Lm-specific hly promoter and secretion based on the LLO-specific signal sequence (28, 29). Specifically, the coding and non-coding sequences that correspond to each peptide (Supplementary Table 1) were annealed together and ligated in-frame into the PstI and StuI sites within the coding sequence for hen egg ovalbumin. Peptide antigens introduced in this site form a recombinant fusion protein containing the desired antigen (amino-terminus) and a truncated form of ovalbumin (carboxy-terminus) that primes antigen-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (28, 29). Relevant portions of each construct were verified by DNA sequencing. Lm protein preparation, SDS gel electrophoresis, and blotting using anti-HA antibody (clone HA-11, Covance) were performed as described (28, 29). For infection, Lm was grown to log phase in brain heart infusion media (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) containing chloramphenicol (20 μg/mL) at 37°C, washed and diluted with saline to a final concentration of 1 × 106 CFUs per 200 μL and injected intravenously into mice as described (28, 29). Lm ΔActA cannot spread from infected cells into adjacent non-infected cells, is rapidly cleared after infection, and therefore allows the use of higher inocula to optimally prime the expansion of pathogen-specific CD4+ T cells (29). The virulent Salmonella typhimurium (ST) strain SL1344 has been described (21, 25), and was grown to early log phase in brain heart infusion broth at 37oC. For infections, 1 × 102 ST CFUs were washed and diluted in saline (200 μL) and injected intravenously into mice.

Statistics

The differences in mean numbers of recoverable bacterial CFUs between groups of mice were evaluated using the Student’s t test with p <0.05 taken as statistically significant (GraphPad Prism Software).

RESULTS

Identification of naturally-occurring FliC431–439-derived APLs

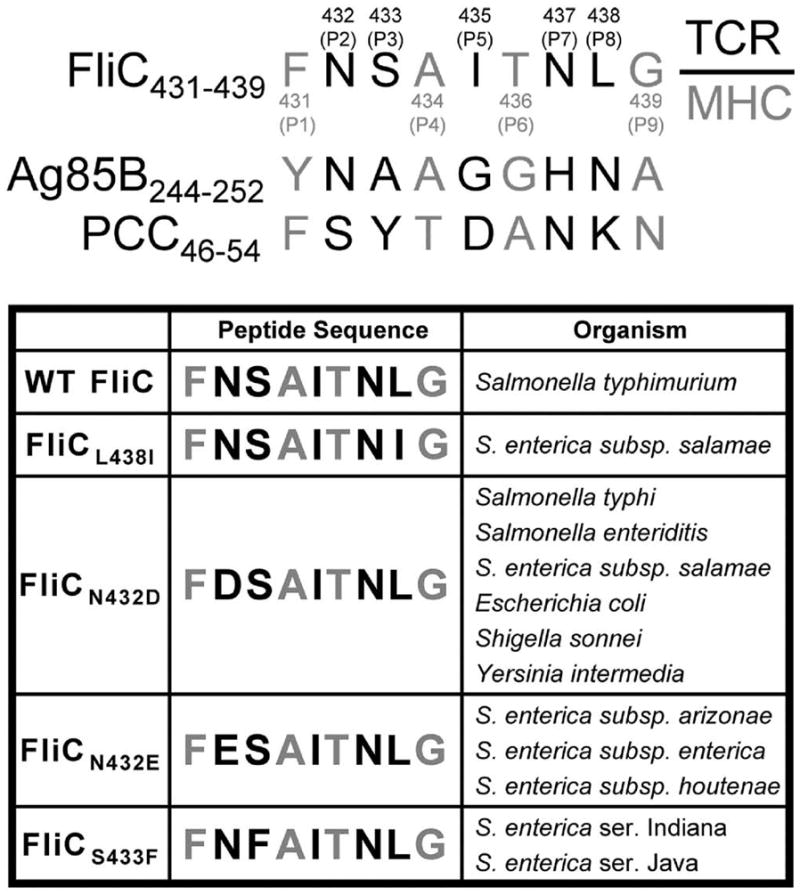

The flagellin structural protein, FliC, is an immune-dominant antigen that confers protection against Salmonella typhimurium infection (21). The peptide that spans amino acids 431–439 within FliC are presented by MHC class II I-Ab as CD4+ T cells with specificity for this peptide are readily identified in naïve C57BL/6 mice and cell lines derived from these mice after stimulation with heat-killed Salmonella (25, 30). Alignment with other well-characterized I-Ab peptides reveals the putative MHC class II anchor and TCR contact residues within the FliC431–439 peptide (Fig 1) (31–34). An essential role for amino acid positions P1, P4, P6 and P9 in direct contact and anchoring the peptide to I-Ab MHC has been demonstrated through mutational analysis and biochemical-binding/affinity assays (31, 32), and these results have been confirmed by the resolved crystal structure of I-Ab-restricted peptides bound to this MHC molecule (33, 34). These studies reveal amino acids containing large, hydrophobic aromatic side chains are predominantly found at position P1, while amino acids with small, uncharged side chains are frequently present at positions P4, P6 and P9. Accordingly, the phenylalanine corresponding to residue 431 within FliC corresponds to position P1, and alanine434, threonine436, and glycine439 correspond to positions P4, P6, and P9, respectively (Fig 1). The importance of positions P2, P3, P5, P7, and P8 for direct contact with the TCR has also been confirmed by both biochemical and crystallographic experimental approaches (31–34). In turn, residues asparagine432, serine433, isoleucine435, asparagine437, and leucine438 within FliC431–439 correspond to the TCR contact sites at positions P2, P3, P5, P7, and P8, respectively (Fig 1). Therefore to identify potential naturally-occurring APLs within the FliC431–439 peptide antigen, a directed BLAST search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) peptide database was performed for known proteins containing substitutions in these TCR contact sites. The parental FliC431–439 peptide sequence containing substitutions incorporating each of the other 19 possible amino acids at each TCR contact residue were used for this database search. This analysis revealed four naturally-occurring FliC431–439-derived APLs that were each identified within the flagellar FliC protein homologue of various Salmonella serovars and other Gram-negative bacteria known to colonize or invade through the gastrointestinal tract (Fig 1). Interestingly, all of these FliC431–439-derived APLs were identified from human clinical isolates of virulent bacteria (35). Among these FliC431–439-derived APLs, one APL contains a conserved leucine (L) → isoleucine (I) substitution at residue 438 (FliCL438I), which retains an uncharged, hydrophobic residue at position P8, while the other three APLs each contain non-conservative substitutions at either position P2 (FliCN432D, FliCN432E) or position P3 (FliCS433F). In the case of APLs FliCN432D and FliCN432E, an uncharged asparagine (N) residue is replaced by a negatively charged aspartate (D) or glutamate (E) residue, respectively. For APL FliCS433F, the small, hydrophilic serine (S) residue is replaced by a large, hydrophobic phenylalanine (F) residue. The presence of these APLs within the immune-dominant epitope of FliC isolated from clinical samples of Salmonella and other Gram-negative bacterial pathogens suggests altered TCR stimulation may play an important role in controlling the CD4+ T cell response to this antigen.

Figure 1.

Alignment of FliC431–439 with other I-Ab peptides. Putative TCR contact or MHC anchor residues within each peptide are indicated by black and gray font, respectively. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amino acid residues that correspond to each position for the FliC431–439 peptide compared with the indicated residues from antigen-85B (Ag85B) or pigeon cytochrome C (PCC) (top). Alignment of each naturally-occurring FliC431–439 –derived APL compared with the parental FliC431–439 peptide (bottom).

Characterization of FliC431–439-derived APLs in vitro

Salmonella FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells derived from SM1 TCR transgenic mice were used to characterize potential differences in how each naturally-occurring APL compared with the parental wild-type FliC431–439 (WT FliC) peptide primes CD4+ T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation (25). As expected, WT FliC readily primes the proliferation of CD4+ T cells from SM1 TCR transgenic mice. More than 95% of these CD4+ T cells were CFSE dilute by day 5 after stimulation with this peptide at 10 μM and 100 μM, while progressive reductions in percent CFSE dilute cells were found when lower concentrations of WT FliC peptide were used (Fig 2A). Interestingly, while the degree of CFSE dilution for cells stimulated with APL FliCL438I was comparable to cells stimulated with WT FliC at higher peptide concentrations (10 μM and 100 μM), the reduction in CFSE dilution after stimulation with APL FliCL438I did not become apparent until much lower concentrations compared with WT FliC peptide (Fig 2A). In contrast, although stimulation with APLs FliCN432D, FliCN432E, and FliCS433F each triggered some CFSE dilution among FliC-specific CD4+ T cells at the highest peptide concentration, this level of CFSE dilution was significantly reduced compared with cells stimulated with either WT FliC or APL FliCL438I and became rapidly extinguished when a 10-fold reduction in concentration was used for stimulation. Collectively, these results indicate naturally-occurring FliC431–439-derived APLs either stimulate CD4+ T cell proliferation more potently (APL FliCL438I) or less potently (APLs FliCN432D, FliCN432E, and FliCS433F) compared with the parental WT FliC431–439 peptide.

Figure 2.

FliC-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation and activation after in vitro stimulation. A. CFSE dilution in SM1 CD4+ T cells after stimulation with WT FliC peptide or each APL (line histogram) at the indicated concentration, or after stimulation with Control peptide (shaded histogram, 10 μM) for 5 days. Numbers in each plot indicate the percent CFSElo cells. B. CD25, CD44, CD62L and Annexin V expression by FliC-specific CD4+ T cells after stimulation with 10 μM WT FliC or each APL (line histogram) or Control peptide (shaded histogram) for 5 days. These results are representative of three independent experiments each with similar results.

Based on these differences in proliferation, the impact of stimulation with each APL compared to the parental WT FliC peptide on T cell activation by FliC-specific CD4+ T cells were quantified. Consistent with their ability to readily prime proliferation, CD4+ T cells stimulated with WT FliC and APL FliCL438I dramatically up-regulated CD25 and CD44 expression and down-regulated CD62L expression (Fig 2B). Conversely and consistent with the weak levels of proliferation, stimulation with APLs FliCN432E or FliCS433F did not cause appreciable changes in CD25, CD44 or CD62L expression and the expression level for each was essentially identical to cells stimulated with an irrelevant control peptide. Interestingly, increased CD25 and CD44 expression was found after stimulation with APL FliCN432D albeit to a lesser extent than cells stimulated with either WT FliC or APL FliCL438I peptides (Fig 2B). Importantly, these differences in CD4+ T cell proliferation and activation triggered by WT FliC peptide compared with each APL are not due to differences in apoptotic cell death because no significant differences in the levels of Annexin V expression were observed (Fig 2B). Therefore, the expression of cell surface markers associated with T cell activation (CD25 and CD44 up-regulation, CD62L down-regulation) directly correlates with the robust proliferation of FliC-specific CD4+ T cells after stimulation with WT FliC and APL FliCL438I, while reduced or minimal changes in the expression of each marker is associated with only limited proliferation after stimulation with APLs FliCN432D, FliCN432E or FliCS433F.

These differences in proliferation and expression of T cell activation markers were extended to explore potential differences in CD4+ T cell differentiation by measuring the production of T-helper lineage-defining cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-17 representative of Th1, Th2, and Th17 lineages, respectively. Stimulation with WT FliC peptide primed IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells at higher peptide concentrations (10 μM and 1 μM), and the level of IFN-γ production was dramatically diminished as the concentration of WT FliC peptide was reduced to 0.1 μM (Fig 3A). Interestingly, while APL FliCL438I compared with WT FliC primed proliferation to a similar or greater extent at all peptide concentrations tested, IFN-γ production was markedly reduced at relatively high peptide concentrations (10 μM and 1 μM), but was only marginally reduced and exceeded the level present in WT FliC-stimulated cells when lower peptide concentrations were used (0.1 μM) (Fig 3A). Furthermore, the level of IFN-γ production by cells stimulated with APLs FliCN432D, FliCN432E, and FliCS433F was essentially at background levels and comparable to cells stimulated with an irrelevant peptide control. Importantly, the reduced IFN-γ production by cells stimulated with each FliC431–439-derived APL compared with WT FliC peptide was not associated with a reciprocal increase in the production of either IL-4 or IL-17, as the levels for both of these cytokines remained at the limits of detection for all stimulated cells quantified using both intracellular cytokine staining and ELISA.

Figure 3.

Reduced IFN-γ and T-bet expression after stimulation with each APL compared with WT FliC peptide. A. Percent IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells after stimulation with each peptide at the indicated concentration. Numbers in each plot represent percent IFN-γ+ cells among FliC-specific CD4+ T cells. B. T-bet expression after stimulation with WT FliC or each APL (line histogram) and Control peptide (shaded histogram) at the indicated peptide concentration. Numbers in each plot indicate mean fluorescent intensity of T-bet staining. These results are representative of at least three independent experiments each with similar results.

Given the importance of the T-box transcription factor T-bet in CD4+ T cell IFN-γ production and Th1 differentiation, additional experiments quantified relative T-bet expression in FliC-specific CD4+ T cells stimulated with WT FliC or each APL peptide (36, 37). Levels of T-bet expression were found to be directly correlated with the production of IFN-γ. The mean fluorescent intensity for T-bet expression in cells stimulated with WT FliC peptide at the higher peptide concentration (10 μM) was dramatically increased (~7-fold) compared with cells stimulated with an irrelevant control peptide, and this level of T-bet expression progressively diminished to background levels when the peptide concentration was reduced. In contrast but completely consistent with the level of IFN-γ production, T-bet expression in cells stimulated with APL FliCL438I compared with WT FliC peptide was reduced 20% at the 10 μM peptide concentration, but did not return to levels comparable to cells stimulated with an irrelevant control peptide even after dilution to 0.1 μM (Fig 3B). As expected, T-bet expression for FliC-specific CD4+ T cells stimulated with APLs FliCN432D, FliCN432E, or FliCS433F were each only at background levels consistent with the absence of IFN-γ production. Taken together, these results demonstrate that although APL FliCL438I and WT FliC both efficiently prime CD4+ T cell proliferation, CD25 and CD44 up-regulation, and CD62L down-regulation at relatively high peptide concentrations (10 μM), stimulation with WT FliC compared to APL FliCL438I primes significantly more IFN-γ production which is associated with increased T-bet expression. However, at lower peptide concentrations (0.1 μM), IFN-γ production and T-bet expression is maintained for cells stimulated with APL FliCL438I but not WT FliC peptide. These results reflect important differences in CD4+ T cell differentiation following stimulation with each of these naturally-occurring antigens.

Characterization of FliC431–439-derived APLs in vivo

Based on these stark contrasts in degree of T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation between each naturally-occurring FliC431–439-derived APL and WT FliC peptide after stimulation in vitro, additional experiments sought to characterize potential differences in the expansion and differentiation of FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells after in vivo stimulation. For these experiments, purified WT FliC peptide, APL FliCL438I, APL FliCN432D (representative of results with APLN432E and APLS433F), and an irrelevant control peptide were each intravenously inoculated into mice adoptively transferred with congenically-marked (CD45.1+) FliC-specific CD4+ T cells from SM1 TCR transgenic mice one day prior. Both purified WT FliC peptide and APL FliCL438I primed robust expansion of FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cells – more than 100-fold increase in percentages and total numbers of CD45.1+CD4+ T cells were present in mice inoculated with WT FliC or APL FliCL438I compared with mice inoculated with irrelevant control peptide (Fig 4A and 4B). In contrast but in complete agreement with the weak levels of proliferation after stimulation in vitro, intravenous inoculation with APL FliCN432D did not prime significant CD4+ T cell expansion as the percent and total numbers of CD45.1+CD4+ T cells recovered from these mice were not significantly different from mice inoculated with irrelevant control peptide (Fig 4A and 4B). When cytokine production by FliC-specific CD4+ T cells stimulated in vivo was quantified, the overall number of IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells was markedly reduced for FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ cells primed with APL FliCL438I compared with WT FliC peptide following ex vivo stimulation with WT FliC peptide (Fig 4C). Importantly, this reduction in IFN-γ production by FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ cells primed with APL FliCL438I compared with WT FliC peptide reflect intrinsic differences due to in vivo priming as similar reductions were found when APL FliCL438I was used for ex vivo stimulation (Fig 4C). Furthermore, FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cells produced no detectable IFN-γ when primed in vivo with APL FliCN432D or the irrelevant control peptide after stimulation ex vivo with either WT FliC peptide or each APL (Fig 4C). Therefore, despite either enhanced or reduced levels of proliferation, markedly reduced IFN-γ production after stimulation with each APL compared with the WT FliC peptide is observed under non-infection conditions in vivo.

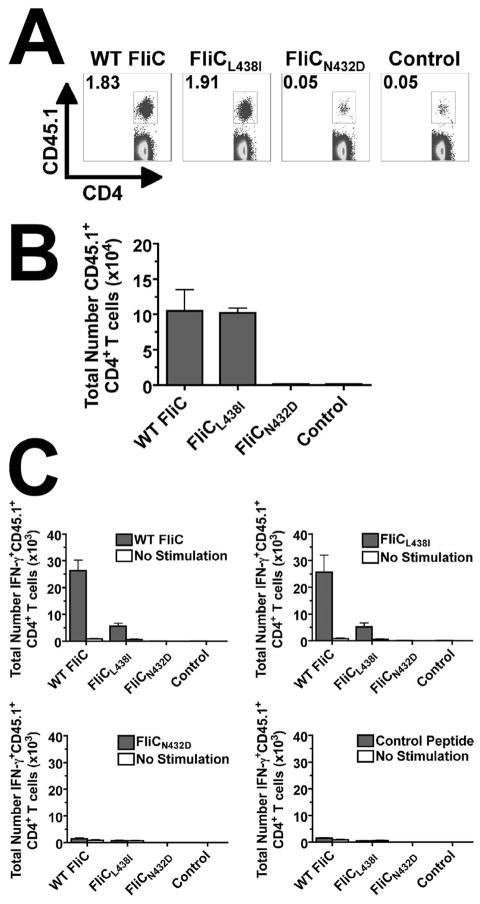

Figure 4.

Pathogen-specific CD4+ T cell expansion and cytokine production after in vivo stimulation. A. Percent FliC-specific (CD45.1+) T cells among CD4+ splenocytes. Number in each plot indicates percent CD45.1+ cells among CD4+ T cells. B. Total number of CD45.1+CD4+ T cells day 5 after intravenous injection of each peptide (50 μg). C. Total number of IFN-γ producing CD45.1+CD4+ T cells for mice described in A after ex vivo peptide stimulation (10 μM; shaded bar) with either WT FliC (top left), FliCL438I (top right), FliCN432D (bottom left), or Control peptide (bottom right) compared to no stimulation control (open bar). These results are representative of two independent experiments each with similar results containing six mice per group. Bar, standard error.

Stimulation with FliC431–439-derived APLs expressed in Listeria monocytogenes

Additional experiments sought to characterize how stimulation with WT FliC peptide and each APL would impact CD4+ T cell priming during experimental infection in vivo because infection triggers complex cascades of immune cytokines and signaling molecules not reproduced by stimulation with purified peptide alone. Since even aflagellated Salmonella retains a high degree of virulence in C57BL/6 mice (38), this natural vector could not be used for priming FliC-specific CD4+ T cells after infection in vivo. Therefore, recombinant Lm was engineered to express either WT FliC or each FliC-derived APL. For these experiments, the attenuated Lm ΔActA parental strain was used allowing a relatively high bacterial inoculum to be used that optimizes the priming and expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells after recombinant Lm infection (29). The coding sequence for either the WT FliC peptide or each APL was cloned behind the Lm-specific hly promoter with an N-terminus listeriolysin O-specific signal sequence that allows each recombinant protein to be secreted by the bacterium (Fig 5A). The uniform expression and secretion of the recombinant proteins that contain either the WT FliC peptide, each APL, or control peptide antigen was verified by protein immune-blotting using antibody against the HA tag (Fig 5B). Although protective immunity to Lm infection is predominantly mediated by CD8+ T cells, we and others have shown infection with either virulent or Lm ΔActA also primes the robust expansion of CD4+ T cells with specificity to both endogenous Lm or recombinant antigens secreted by Lm (11, 27, 29). Similar to results after stimulation with purified peptide, mice infected with Lm expressing either WT FliC (rLM-WT) or APL FliCL438I (rLM-L438I) each contained robust FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cell expansion, while mice infected with Lm expressing APL FliCN432D (rLM-N432D) contained only background levels of CD45.1+CD4+ T cells comparable to levels found in mice infected with Lm expressing an irrelevant control antigen (rLM-Control) (Fig 5C).

Figure 5.

FliC-specific CD4+ T cell expansion and cytokine production after recombinant Lm infection. A. Construct map indicating placement of coding sequences for WT FliC and each APL within the pAM401-based expression vector (Phly, Lm hly promoter; SS, signal sequence of hly; HA, hemagglutinin tag; cat, chloramphenicol acetlytransferase) (left). B. Western blot of supernatant protein from rLM-WT (lane 1), rLM-L438I (lane 2), rLM-N432D (lane 3), and rLM-Control (lane 4) (right). C. Total number of FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cells at day 3 (left) and day 30 (right) after infection with each recombinant Lm strain. D. Percent IFN-γ producing CD45.1+CD4+ T cells after ex vivo peptide stimulation with WT FliC peptide (10 μM) among splenocytes day 3 after infection with each recombinant Lm strain. Number in each plot indicates percent IFN-γ+ cells among CD45.1+CD4+ T cells. E. Total number of IFN-γ producing CD45.1+CD4+ T cells among splenocytes after ex vivo stimulation with WT FliC peptide (10 μM; shaded bar) or no peptide (open bar) day 3 (left) or day 30 (right) following recombinant Lm infection. These results are combined from at least two independent experiments each with similar results containing four to six mice per group. Bar, standard error.

Related experiments quantified IFN-γ production by FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cells after stimulation with WT FliC or each APL administered in the context of recombinant Lm infection. Since Lm ΔActA at an inocula of 106 CFUs triggers the robust production of cytokines such as IL-12 and type I IFN that together synergistically primes IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells (39), we hypothesized that the observed differences in IFN-γ production relative to the degree of proliferation for FliC-specific CD4+ T cells primed with WT FliC compared with APL FliCL438I would be normalized in this highly polarizing Th1 cytokine environment. Alternatively, persistent reductions in IFN-γ production relative to the degree of proliferation for FliC-specific CD4+ T cells primed with APL FliCL438I compared with WT FliC peptide would demonstrate a critical role for TCR stimulation in controlling CD4+ T cell IFN-γ production even in the cytokine milieu triggered by Lm ΔActA infection. Remarkably and in complete agreement with stimulation studies using purified peptide, IFN-γ producing FliC-specific CD45.1+CD4+ T cells were drastically reduced in mice primed with rLM-L438I compared with rLM-WT (~ 60% reduction, p <0.05) (Fig 5D and 5E). As expected, the few cells that did not appreciably expand after infection with rLM-N432D also did not produce detectable amounts of IFN-γ relative to mice inoculated with recombinant Lm expressing an irrelevant antigen (rLM-Control) (Fig 5D and 5E). Additional experiments extended the time course for these experiments to characterize the survival of CD4+ T cells at later time points after infection with each recombinant Lm. By day 30 post-infection, the numbers of CD45.1+CD4+ T cells for mice infected with either rLM-WT and rLM-L438I had contracted ~20-fold compared with day 3 levels (Fig 5C). Interestingly, despite this large degree of contraction, the ~60% reduction in number of IFN-γ producing CD45.1+CD4+ T cells was maintained for rLM-L438I infected compared with rLM-WT infected mice through this later time point (Fig 5E).

IFN-γ production dictates CD4+ T cell protective potency

Given the overall importance of CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ in host defense against intracellular bacterial pathogens like Salmonella (19–24), additional experiments sought to characterize the role of IFN-γ production by Salmonella-specific CD4+ T cells in immunity against this infection. Mice primed initially with recombinant Lm expressing WT FliC or each APL were challenged with a lethal dose of virulent Salmonella typhimurium (ST) 30 days after Lm infection, and the degree of protection was quantified by enumerating the number of recoverable ST CFUs from each group of mice in the spleen and liver. Compared with mice transferred with FliC-specific CD4+ T cells alone, significant differences in ST CFUs were found only for mice primed with rLM-WT where an approximate 10-fold reduction (p < 0.05) in ST bacterial burden was found day 5 after challenge (Fig 6). By contrast, mice primed with rLM-L438I, rLM-N432D, or rLM-Control each had significantly increased ST CFUs compared to mice primed with rLm-WT and at levels not significantly different to control mice that only received FliC-specific CD4+ T cells without Lm infection (Fig 6). This observed reduction in ST CFUs conferred by infection with rLM-WT cannot be attributed to non-specific immune activation secondary to Lm ΔActA infection as mice primed with rLM-L438I, rLM-N432D, and rLM-Control were each infected with the same inocula of Lm ΔActA. Furthermore, since similar numbers of FliC-specific CD4+ T cells are present both during expansion and after T cell contraction (Fig 5B) for mice primed with WT FliC and APL FliCL438I, differences in absolute number of FliC-specific CD4+ T cells alone also cannot account for reductions in ST CFUs conferred by rLM-WT compared to rLM-L438I. Despite the significant reduction in ST CFUs observed in mice primed with rLM-WT compared to mice primed with rLM-L438I, rLM-N432D, or rLM-Control, the overall survival and time to death between these groups of mice was not significantly different. Regardless of initial priming condition, the majority of mice in each group became moribund or died by day 7 post-challenge. Taken together, these results indicate a critical role for IFN-γ production by pathogen-specific CD4+ T cells in host defense against Salmonella infection and demonstrate how alterations in TCR stimulation can have dramatic impacts on CD4+ T cell differentiation and protective potency.

Figure 6.

WT FliC peptide expressed in recombinant Lm confers protection to Salmonella. Number of recoverable Salmonella CFUs in the spleen (top) and liver (bottom) of mice day 5 after challenge with virulent Salmonella typhimurium. Each group of mice were adoptively transferred with FliC-specific CD4+ T cells and initially infected with the indicated recombinant Lm or no Lm infection 30 days prior to Salmonella challenge. These data represent eight to fourteen mice per group combined from four independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

CD4+ T cell activation and differentiation requires at least three distinct, yet inter-related stimulatory signals mediated through the T cell receptor, co-stimulation receptors, and receptors for specific “inflammatory” cytokines (7–15). Although these signals together uniformly stimulate T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation, each signal has been proposed to play specific and defined roles in this process. For example, the antigen specificity for the T cell response is controlled by stimulation through the T cell receptor, while lineage differentiation is believed to be largely dictated by the presence or absence of specific cytokines. Unfortunately, since these roles have been primarily characterized following T cell stimulation in vitro or during non-infection conditions in vivo, the precise role for each stimulatory signal in controlling the specific incremental steps required for T cell activation during infection when the expression levels for all T cell stimulatory signals are drastically altered remains largely undefined. Moreover, the impact of changes in each stimulatory signal on CD4+ T cell-mediated protection to infection is unknown. Accordingly, the importance of TCR stimulation in CD4+ T cell activation was experimentally examined by measuring potential differences in proliferation, expansion, and differentiation after stimulation under non-infection and infection conditions with the Salmonella-derived FliC431–439 MHC class II peptide or APLs containing substitutions in TCR contact residues derived from this peptide. In these experiments, naturally-occurring altered peptide ligands containing amino acid substitutions in TCR contact residues within the FliC431–439 peptide were identified and used for stimulation to explore how natural ligands from other bacterial pathogens may control the CD4+ T cell response to this antigen. Among these naturally-occurring APLs, one primed FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation more potently while others primed CD4+ T cell proliferation less potently compared with the parental wild-type FliC peptide following stimulation in vitro. Despite differences in proliferation, these APLs primed dramatically reduced IFN-γ production following stimulation in vivo. Importantly, the protective potency of these CD4+ T cells after challenge with virulent Salmonella was directly correlated with IFN-γ production regardless of expansion magnitude, and this increased protective potency was reflected in the significant reduction in Salmonella bacterial burden after secondary challenge. Interestingly, however, these reductions in Salmonella CFUs were not associated with detectable difference in survival. This observation may be due to the inherent defects in innate host defense against virulent Salmonella typhimurium infection present in C57BL/6 mice. Nevertheless, these results collectively demonstrate a critical and previously unanticipated role for TCR stimulation in controlling CD4+ T cell differentiation into protective, IFN-γ producing effector T cells.

A two-step model for the initial up-regulation and eventual stabilization of T-bet expression in naïve CD4+ T cells required for IFN-γ production and Th1 differentiation has been proposed (40, 41). In this model, the initial expression of T-bet is dependent on TCR stimulation and IFN-γ production, while the latter phase of T-bet stabilization is dependent on IL-12 receptor stimulation. Interestingly, termination of TCR stimulation permitted up-regulation of IL-12 receptor expression required for maintaining T-bet expression (40). Our demonstration that APL FliCL438I is a more potent inducer of FliC-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation compared with WT FliC yet only weakly up-regulates IFN-γ production at high concentrations is consistent with this hypothesis. The discordant expression of T-bet with proliferation potency after APL FliCL438I stimulation may be due to stronger TCR stimulation that inhibits the latter phase of T-bet expression required for the stabilization of IFN-γ production by FliC-specific CD4+ T cells. This notion that APL FliCL438I compared to WT FliC stimulates stronger TCR signaling is supported by our results demonstrating T-bet expression and IFN-γ production by FliC-specific CD4+ T cells stimulated with APL FliCL438I is less perturbed by reductions in peptide concentration (Fig 3A). Additional experiments that more specifically characterize the kinetics of T-bet, IFN-γ, and IL-12 receptor expression are needed to elucidate the mechanism underlying this observed discordance between CD4+ T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production.

The identification of naturally-occurring APLs within protective immune-dominant antigens suggests that alterations in TCR stimulation may be used by pathogenic bacteria to modulate or avoid the pathogen-specific T cell response. This notion is bolstered by the identification of naturally-occurring APLs derived from Salmonella FliC431–439 among human clinical isolates of various invasive bacterial pathogens that we describe in this study (Fig 1). For example, APL FliCN432D has been described in over 100 unique Salmonella clinical isolates derived from serovars that have the potential to cause typhoidal or non-typhoidal disease in humans (35, 42). Moreover, this APL has also been identified in numerous clinical isolates of other invasive Gram-negative human pathogens such as Shigella sonnei, Yersinia intermedia, and both toxigenic and hemorrhagic forms of Escherichia coli (43–49). Collectively, the identification of APLs within FliC431–439 from this diverse range of bacterial pathogens that cause clinical disease indicates pathogens containing these mutations not only retain virulence, but may be more capable of enhanced pathogenesis associated with immune evasion of protective T cells. Although our experiments examined the response for CD4+ T cells with unique specificity to one Salmonella-specific immune-dominant peptide antigen, these results nevertheless provide experimental evidence implicating alterations in CD4+ T cell TCR stimulation as a potential immune evasion strategy utilized by bacterial pathogens. Therefore, further investigation characterizing the differences in virulence properties and immune response to pathogens that contain APLs in immune-dominant T cell antigens is needed, and will likely reveal novel and important information on the pathogenesis and immune response to these infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Marc Jenkins, Stephen McSorley, David Masopust, and Vaiva Vezys for helpful discussions, and Dr. Stephen McSorley for the gift of SM1 TCR transgenic mice and critical review of this manuscript.

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health Grant K08HD51584, the Minnesota Vikings Children’s Fund, the Minnesota Medical Foundation, and the University of Minnesota Grant-in-Aid of Research.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 determines tolerance versus full activation of naive CD8 T cells: dissociating proliferation and development of effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1141–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway CA, Jr, Bottomly K. Signals and signs for lymphocyte responses. Cell. 1994;76:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gett AV, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Geginat J. T cell fitness determined by signal strength. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:355–360. doi: 10.1038/ni908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lafferty KJ, Prowse SJ, Simeonovic CJ, Warren HS. Immunobiology of tissue transplantation: a return to the passenger leukocyte concept. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1:143–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkins MK, Johnson JG. Molecules involved in T-cell costimulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90054-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver CT, Hawrylowicz CM, Unanue ER. T helper cell subsets require the expression of distinct costimulatory signals by antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8181–8185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey KA, Mescher MF. IL-21 promotes differentiation of naive CD8 T cells to a unique effector phenotype. J Immunol. 2007;178:7640–7648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orgun NN, Mathis MA, Wilson CB, Way SS. Deviation from a strong Th1-dominated to a modest Th17-dominated CD4 T cell response in the absence of IL-12p40 and type I IFNs sustains protective CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:4109–4115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valenzuela J, Schmidt C, Mescher M. The roles of IL-12 in providing a third signal for clonal expansion of naive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6842–6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: the third member of the effector T cell trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy KM, Reiner SL. The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:933–944. doi: 10.1038/nri954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamura T, Ariga H, Kinashi T, Uehara S, Kikuchi T, Nakada M, Tokunaga T, Xu W, Kariyone A, Saito T, Kitamura T, Maxwell G, Takaki S, Takatsu K. The role of antigenic peptide in CD4+ T helper phenotype development in a T cell receptor transgenic model. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1691–1699. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeiffer C, Stein J, Southwood S, Ketelaar H, Sette A, Bottomly K. Altered peptide ligands can control CD4 T lymphocyte differentiation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1569–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zehn D, Lee SY, Bevan MJ. Complete but curtailed T-cell response to very low-affinity antigen. Nature. 2009;458:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nature07657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess J, Ladel C, Miko D, Kaufmann SH. Salmonella typhimurium aroA- infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-alpha beta cells and IFN-gamma in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J Immunol. 1996;156:3321–3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones BD, Falkow S. Salmonellosis: host immune responses and bacterial virulence determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McSorley SJ, Cookson BT, Jenkins MK. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2000;164:986–993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittrucker HW, Kaufmann SH. Immune response to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:457–463. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monack DM, Mueller A, Falkow S. Persistent bacterial infections: the interface of the pathogen and the host immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:747–765. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauciel C. Role of CD4+ T cells and T-independent mechanisms in acquired resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Immunol. 1990;145:1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McSorley SJ, Asch S, Costalonga M, Reinhardt RL, Jenkins MK. Tracking salmonella-specific CD4 T cells in vivo reveals a local mucosal response to a disseminated infection. Immunity. 2002;16:365–377. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brundage RA, Smith GA, Camilli A, Theriot JA, Portnoy DA. Expression and phosphorylation of the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11890–11894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foulds KE, Zenewicz LA, Shedlock DJ, Jiang J, Troy AE, Shen H. Cutting edge: CD4 and CD8 T cells are intrinsically different in their proliferative responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:1528–1532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orr MT, Orgun NN, Wilson CB, Way SS. Cutting Edge: Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes expressing a single immune-dominant peptide confers protective immunity to herpes simplex virus-1 infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4731–4735. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ertelt JM, Rowe JH, Johanns TM, Lai JC, McLachlan JB, Way SS. Selective priming and expansion of antigen-specific Foxp3- CD4+ T cells during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2009;182:3032–3038. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, McSorley SJ, Jameson SC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh Y, Kajino K, Ogasawara K, Takahashi A, Namba K, Negishi I, Matsuki N, Iwabuchi K, Kakinuma M, Good RA, Onoe K. Interaction of pigeon cytochrome c-(43–58) peptide analogs with either T cell antigen receptor or I-Ab molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12047–12052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariyone A, Higuchi K, Yamamoto S, Nagasaka-Kametaka A, Harada M, Takahashi A, Harada N, Ogasawara K, Takatsu K. Identification of amino acid residues of the T-cell epitope of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alpha antigen critical for Vbeta11(+) Th1 cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4312–4319. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4312-4319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Dai S, Crawford F, Fruge R, Marrack P, Kappler J. Alternate interactions define the binding of peptides to the MHC molecule IA(b) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8820–8825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132272099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu Y, Rudensky AY, Corper AL, Teyton L, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of MHC class II I-Ab in complex with a human CLIP peptide: prediction of an I-Ab peptide-binding motif. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:1157–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McQuiston JR, Parrenas R, Ortiz-Rivera M, Gheesling L, Brenner F, Fields PI. Sequencing and comparative analysis of flagellin genes fliC, fljB, and flpA from Salmonella. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1923–1932. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.1923-1932.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science (New York, NY) 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikeda JS, Schmitt CK, Darnell SC, Watson PR, Bispham J, Wallis TS, Weinstein DL, Metcalf ES, Adams P, O’Connor CD, O’Brien AD. Flagellar phase variation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contributes to virulence in the murine typhoid infection model but does not influence Salmonella-induced enteropathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3021–3030. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3021-3030.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Way SS, Havenar-Daughton C, Kolumam GA, Orgun NN, Murali-Krishna K. IL-12 and type-I IFN synergize for IFN-gamma production by CD4 T cells, whereas neither are required for IFN-gamma production by CD8 T cells after Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4498–4505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz EG, Mariani L, Radbruch A, Hofer T. Sequential Polarization and Imprinting of Type 1 T Helper Lymphocytes by Interferon-gamma and Interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;30:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullen AC, High FA, Hutchins AS, Lee HW, Villarino AV, Livingston DM, Kung AL, Cereb N, Yao TP, Yang SY, Reiner SL. Role of T-bet in commitment of TH1 cells before IL-12-dependent selection. Science (New York, NY) 2001;292:1907–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1059835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker S, Hardy J, Sanderson KE, Quail M, Goodhead I, Kingsley RA, Parkhill J, Stocker B, Dougan G. A novel linear plasmid mediates flagellar variation in Salmonella Typhi. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang F, Yang J, Zhang X, Chen L, Jiang Y, Yan Y, Tang X, Wang J, Xiong Z, Dong J, Xue Y, Zhu Y, Xu X, Sun L, Chen S, Nie H, Peng J, Xu J, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Wen Y, Yao Z, Shen Y, Qiang B, Hou Y, Yu J, Jin Q. Genome dynamics and diversity of Shigella species, the etiologic agents of bacillary dysentery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6445–6458. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kay BA, Wachsmuth K, Gemski P, Feeley JC, Quan TJ, Brenner DJ. Virulence and phenotypic characterization of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from humans in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:128–138. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.1.128-138.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beutin L, Strauch E. Identification of sequence diversity in the Escherichia coli fliC genes encoding flagellar types H8 and H40 and its use in typing of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O8, O22, O111, O174, and O179 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:333–339. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01627-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farmer JJ, 3rd, Fanning GR, Davis BR, O’Hara CM, Riddle C, Hickman-Brenner FW, Asbury MA, Lowery VA, 3rd, Brenner DJ. Escherichia fergusonii and Enterobacter taylorae, two new species of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:77–81. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.1.77-81.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasko DA, Rosovitz MJ, Myers GS, Mongodin EF, Fricke WF, Gajer P, Crabtree J, Sebaihia M, Thomson NR, Chaudhuri R, Henderson IR, Sperandio V, Ravel J. The pangenome structure of Escherichia coli: comparative genomic analysis of E. coli commensal and pathogenic isolates. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6881–6893. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tobe T, Hayashi T, Han CG, Schoolnik GK, Ohtsubo E, Sasakawa C. Complete DNA sequence and structural analysis of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence factor plasmid. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5455–5462. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5455-5462.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang WL, Bielaszewska M, Liesegang A, Tschape H, Schmidt H, Bitzan M, Karch H. Molecular characteristics and epidemiological significance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2134–2140. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2134-2140.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.