Abstract

Objective

To evaluate an entertainment-based patient decision aid for prostate cancer screening among patients with low or high health literacy.

Methods

Male primary care patients from two clinical sites, one characterized as serving patients with low health literacy (n=149) and the second as serving patients with high health literacy (n=301), were randomized to receive an entertainment-based decision aid for prostate cancer screening or an audiobooklet-control aid with the same learner content but without the entertainment features. Postintervention and 2-week follow-up assessments were conducted.

Results

Patients at the low-literacy site were more engaged with the entertainment-based aid than patients at the high-literacy site. Overall, knowledge improved for all patients. Among patients at the low-literacy site, the entertainment-based aid was associated with lower decisional conflict and greater self-advocacy (i.e., mastering and obtaining information about screening) when compared to patients given the audiobooklet. No differences between the aids were observed for patients at the high-literacy site.

Conclusions

Entertainment education may be an effective strategy for promoting informed decision making about prostate cancer screening among patients with lower health literacy.

Practice Implications

As barriers to implementing computer-based patient decision support programs decrease, alternative models for delivering these programs should be explored.

Keywords: patient decision aids, prostate cancer screening, health literacy

1. Introduction

Leading professional organizations recommend that men be educated about the potential benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening before they undergo testing [1–3]. Such recommendations coincide with the development of many different decision-support tools, or decision aids, to assist men in making informed decisions about screening [4]. A recent systematic review concluded that decision aids increase patients’ knowledge of prostate cancer and screening, lead patients to want a more active role in decision making, and leave patients more confident about their decisions [5].

Providing decision support to patients with low health literacy is a challenging task [6,7]. Reading level clearly affects health literacy. In the United States, 26% of the adult population reads at or below the 6th grade level, and another 20% reads at the 7th or 8th grade level [8]. Low health literacy is more prevalent among African Americans, persons with fewer than 12 years of schooling, persons whose primary language is Spanish, and persons older than 50 years [8]. According to the Institute of Medicine, health literacy includes skills beyond reading and writing—such as numeracy, speech and speech comprehension, and basic math calculation—and relies on cultural and conceptual knowledge [9]. Current decision aids do not consider these additional skills and, for this reason, are of limited utility to a large segment of the adult population.

A promising approach to the delivery of decision support to patients with low health literacy relies on interactive multimedia (IMM) to present educational messages within the context of an entertaining story [10–13]. These new media technologies are designed to enhance the engagement of users through real-life experiences and to address their interests and emotions [14–16]. Incorporating entertainment elements into programs targeted to persons with lower health literacy and poor computer skills may promote the engagement of users [17]. Entertainment-education messages have been shown to be highly effective in changing the health behaviors of low-literacy audiences who may not be initially motivated to process a message [12,18]. Nevertheless, the use of IMM and entertainment education to promote informed decision making has been limited [19–21].

In this study of informed decision making for prostate cancer screening among primary care patients, we compared a computerized, interactive, multimedia patient decision aid that includes an entertaining soap-operatic component to an audiobooklet without the interactivity and entertainment features. Two patient groups representing different health-literacy levels were targeted, and the performance of the aids was compared between the low and high health literacy groups.

2. Methods

The study design was a randomized, controlled trial conducted in two clinical settings. Patients were randomized separately in each setting using permuted blocks. An audiobooklet was used as the active control. The Institutional Review Boards of Baylor College of Medicine and the Harris County Hospital District approved the project.

2.1. Setting

The first clinical setting (low health literacy site) was a general medicine clinic in a publicly funded hospital operated by a county health district. Patients served at this site do not have medical insurance, and many have a high school education or less. The second clinical setting (high health literacy site) was a university-affiliated family medicine clinic that serves a generally well-educated and privately insured patient population. Data collection began in January, 2004, and continued through February, 2006.

2.2. Subjects

Eligible subjects were male primary care patients who visited either clinic for nonacute care, who had no history of prostate cancer, and who were 50 to 70 years of age if not African American or were 40 to 70 years of age if African American.

2.3. Flow of the Study

The baseline questionnaire, decision aids, and postintervention evaluations were completed in conjunction with office visits at the study sites. Patients were contacted by telephone before scheduled office visits and in the waiting areas of the study sites. After assessing eligibility and procuring informed consent, patients were randomized to receive either the entertainment-based or the audiobooklet-control aid. The baseline questionnaire was administered to all study subjects; in addition, it was read by a research assistant to all subjects at the low-literacy site. Subjects then completed the decision aid (all subjects completed their assigned aid). Research assistants were available to assist patients with using the aids. Before leaving the study site, subjects also completed a postintervention evaluation. Two weeks after the office visit, subjects completed a follow-up assessment by telephone or by a mailed questionnaire. Research assistants were not blinded to the study.

2.4. Intervention and Control Decision Aids

Design of the intervention decision aid followed the Edutainment Decision Aid Model (EDAM) developed by Jibaja-Weiss and Volk [10]. The EDAM is a tool that helps designers of decision aids combine a carefully crafted storyline with factual medical information. The design objectives were to create a multimedia computer-based aid that considers the limitations of low-literate patients, including naïve computer users, through a user-friendly interface that is similar to a dramatic television program. The aid was structured into two major components: didactic soap-opera episodes integrated with interactive learning modules (ILMs) that complement the content of the episodes. The soap-opera genre was selected because it is a familiar, nonthreatening, and engaging environment that allows behaviors desirable for informed decision making to be modeled, with the goal of promoting the self-efficacy of the viewer [13,22]. The graphical user interface included user-friendly screen backgrounds and illustrations depicting familiar environments (e.g., at home watching television, in a lunchroom at work). Navigational instructions were provided throughout the program with voice-over narration.

The ethnicity of the main character was tailored to the viewer through a series of questions completed upon entering the program. The cast was multiethnic and blue-collar, reflecting the patients targeted at the low-literacy site. The storyline of the soap opera took the main character through the process of making a decision about prostate cancer screening. The soap-operatic segments were interwoven with ILMs that communicated key factual information about prostate cancer and screening. The six ILMs were: 1) basic facts about the prostate; 2) risk factors for prostate cancer; 3) screening tests for prostate cancer; 4) treatment options for prostate cancer; 5) complications of prostate cancer treatment; and 6) a review of the issues (a diagram of the program flow can be found elsewhere [10]). The 6th ILM, Prostate Cancer Testing Decision Review, included a review of the main points of the previous ILMs interleaved with testimonials from several celebrities about the importance of learning about prostate cancer and screening. The key messages from the review module are given in an appendix to this article. Celebrity testimonials emphasized the importance of learning about prostate cancer screening, but offered no endorsement of screening. The final main section of the program was a values-clarification exercise that used a social-matching scenario wherein the viewer is asked to identify a character who most resembles how he feels (i.e., “Pick who is most like you”).

Table 1 summarizes the key design differences between the entertainment-based and the audiobooklet-control aids. The audiobooklet contained the same factual content as the entertainment-based aid, including screen shots taken from the ILMs, and was accompanied by an audio CD with narration. The audiobooklet lacked the interactivity, entertainment component (i.e., soap operas), testimonials, and values-clarification exercise.

Table 1.

Comparison of Entertainment-Based and Audiobooklet Decision Aids.

| Descriptor | Entertainment Aid | Audiobooklet Aid |

|---|---|---|

| General description | Computerized program, interactive, with an entertainment-education component and narration. | Booklet with learner content presented with illustrations and text. Audio CD provides guided narration. |

| Length | Low literacy site: | 18 minutes |

| Mean = 68.4 minutes | ||

| (SD = 23.8) | ||

| High literacy site: | ||

| Mean = 53.1 minutes | ||

| (SD = 14.5) | ||

| User tailoring | Tailored to ethnicity and prostate cancer risk (age, family history, and African- American race) of user. | None |

| Use of text | Minimal use, with bulleted, headline format. | Minimal use, with bulleted, headline format. |

| Interactivity | Uses Interactive Learning Modules to elicit learner input. | None |

| Factual content | Facts about prostate cancer, risk, screening methods, treatment options, complications. | Same as entertainment-based aid. |

| Entertainment education | Telenovella “soap opera” episodes to promote media identification and engagement. | None |

| Testimonials | Uses celebrities to discuss the importance of learning about prostate cancer and screening. | None |

| Values clarification | Social-matching exercise. | None |

SD, standard deviation.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Acceptability of the Decision Aids

The postevaluation included indicators from the Ottawa Decision Aid Centre on acceptability of decision aids: ratings of the amount of information, length of the programs, clarity of the presentation, and balance for or against screening [23].

2.6.2. Engagement with the Entertainment-Based Aid

To more fully explore the users’ experience with the entertainment-based aid, subjects answered 16 questions about the content and presentation of the aid during the postintervention evaluation. The questions were drawn from research on narrative persuasion and the idea that a subject’s attitude toward a message is dependent on the extent to which he or she is involved or absorbed into the narrative [24]. The response format was “yes,” “no,” or “unsure” and addressed four components of the aid: 1) the general look and feel of the program, 2) the soap-operatic segments, 3) the values-clarification exercise, and 4) the celebrity testimonials.

2.6.3. Knowledge of Prostate Cancer and Screening

The primary outcome for this study, the knowledge measure was adapted from measures used in previous studies by the research team [25]. The items were written as questions with options of a “yes,” “no,” or “unsure” response. The content of the questions was drawn from the ILMs and from the factual information in the audioblooklet.

2.6.4. Decisional Conflict Scale

Decisional conflict, as conceptualized by Janis and Mann [26], is a state of uncertainty about options involving risks, tradeoffs, and the potential for regret. Considerable evidence suggests that decision conflict is modifiable by decision aids [4]. We administered the standard 16-item version and a 10-item low-literacy version of the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) [27] at the high-literacy and low-literacy sites, respectively. The standard version includes five subscales: 1) uncertainty or lack of assuredness about the decision, 2) feeling informed about the options and their benefits and risks, 3) feeling clear about one’s personal values in making the decision, 4) feeling social support in making the decision, and 5) feelings of having made an effective decision and planning to follow through. The subscales have excellent internal-consistency reliability (alpha range: 0.78–0.92) and construct validity. The low-literacy version uses a question-and-answer format with three response options: “yes,” “no,” or “unsure.” The version has good internal-consistency reliability (alpha, 0.86) and evidence of responsive to change after a decision aid is delivered. Scoring conventions followed the new DCS manual, wherein scores are expressed on a 0 (low decisional conflict) to 100 (high decisional conflict) scale [28].

2.6.5. Patient Involvement in Health-Care Decision Making: The Patient Self-Advocacy Scale

Patient self-advocacy is the degree to which a patient takes a participative stance in health-care decision making and is reflected in definitions of informed decision making [29]. We used the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale (PSAS) [30] to assess the subjects’ involvement in health-care decision-making interactions— specifically their beliefs about the benefits of acquiring information and the propensity to self-educate—and how this acquired information influences the patient-physician relationship. The three scales of the PSAS are: 1) illness and treatment education (information-seeking beliefs and behaviors), 2) assertiveness (control over health care and interactions with a physician), and 3) mindful nonadherence (the tendency to reject treatments when they fail to meet expectations of the patient). Internal consistency reliability is good (alpha range: .64—.78) and there is evidence of construct validity [30].

The original, 12-item version uses a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The first four statements were adapted for prostate cancer screening; the remaining statements were unchanged from the original version. For the low-literacy site, the PSAS statements were reexpressed as questions. For example, “I am more assertive about my health care needs than most people” became “Are you more assertive about your health care needs than most people?” The adapted response options were “yes,” “no,” and “unsure.”

2.7. Data Analysis

A target sample size of 75 subjects per group was adopted to detect a moderate effect size when comparing the two aids on the knowledge measure. The characteristics of the subjects who completed the 2-week follow-up were compared with those of the subjects lost to follow-up using t-tests and contingency tables with chi-square serving as the test statistic. Postintervention measures of the acceptability of the two decision aids were compared separately for each study site using contingency tables. Among patients who received the entertainment-based aid, responses to the engagement questions were compared across the two study sites using One-way Analysis of Variance. Because we expected differences across study sites in knowledge at the baseline assessment, Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance was used to test for changes in knowledge from the baseline to the 2-week follow-up. Means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. A significant interaction of time (baseline to 2-week follow-up) by intervention group and by study site would suggest that the decision aids performed differently across the two study sites. For the DCS and PSAS measures, Analysis of Covariance was used, with the baseline scores serving as a covariate. Models were run separately for low-literacy and high-literacy subjects because different versions of the measures were used. Means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Controlling for previous PSA testing did not impact the analyses of knowledge scores, DCS, or PSAS measures. The reported findings are therefore not adjusted for previous PSA testing. The analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows, Version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, 2006).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

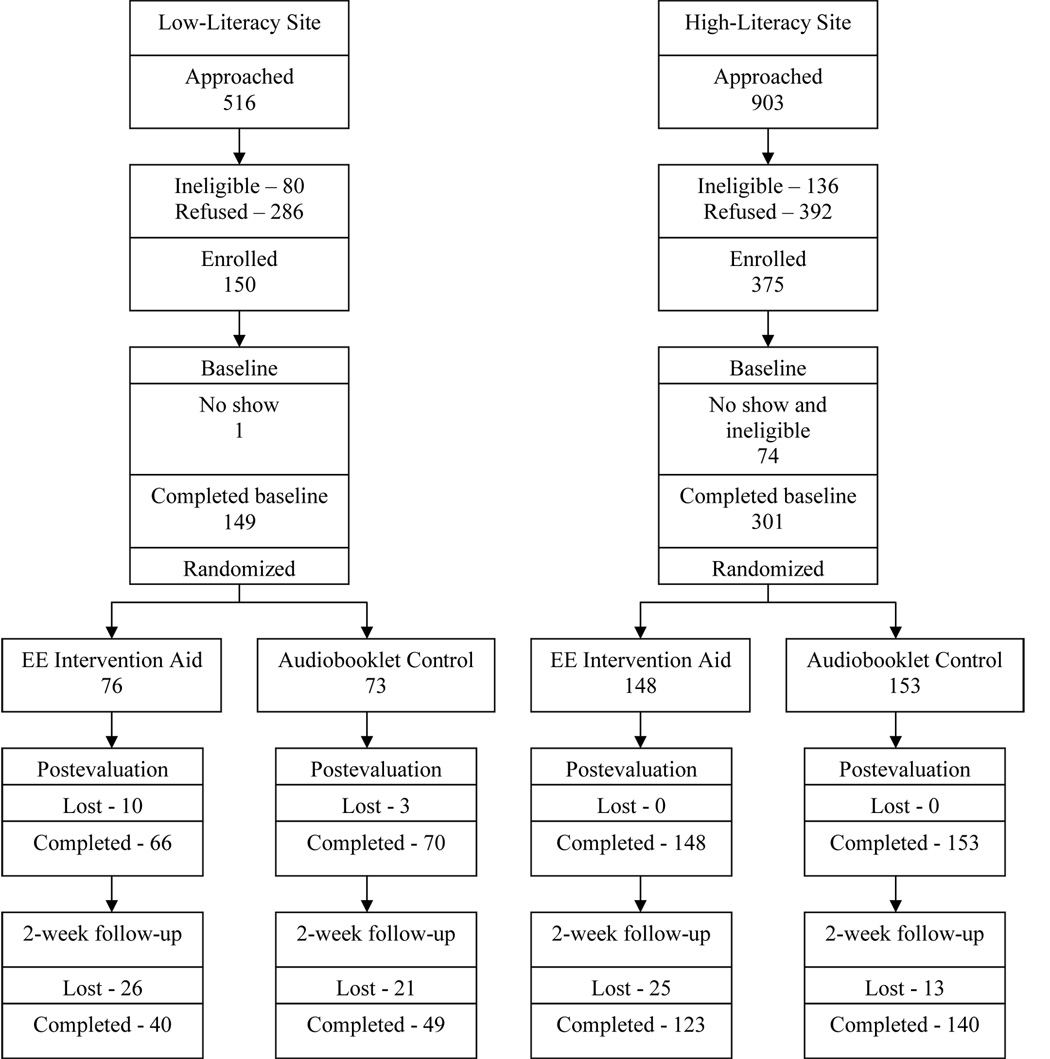

One hundred forty-nine patients at the low-literacy site and 301 patients at the high-literacy site were randomized (Fig. 1). There was no attrition by the time of the postintervention evaluation for the subjects at the high-literacy site, but 13 subjects at the low-literacy site did not complete this evaluation because they were referred to other services at the public hospital or because of time constraints. Eighty-nine (59.7%) of the subjects from the low-literacy site and 263 (84.1%) subjects from the high-literacy site completed the 2-week follow-up.

Figure 1.

Schema for the Study.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the subjects from the two study sites and compares those who did and did not complete the 2-week follow-up. At the low-literacy site, subjects who completed the 2-week follow-up were slightly younger and were more likely to have a family history of prostate cancer and to have had a previous prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Across sites, there were large differences in ethnic composition, having had a previous PSA test, and having had some college training.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Sample.

| Low-Literacy Site | High-Literacy Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed Follow-up |

Lost to Follow- up |

P- Value |

Completed Follow-up |

Lost to Follow- up |

P- Value |

|

| n=89 | n=60 | n=263 | n=38 | |||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean | 55.6 | 52.2 | .005 | 56.5 | 56.5 | .184 |

| SD | 7.3 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 7.1 | ||

| Ethnicity*(%) | ||||||

| African | 73.0 | 72.1 | .201 | 17.1 | 28.9 | .096 |

| American | ||||||

| Hispanic | 9.0 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 7.9 | ||

| White | 18.0 | 14.8 | 64.6 | 44.7 | ||

| Other | 0.0 | 4.9 | 10.6 | 18.4 | ||

| Family history of prostate cancer (%) |

||||||

| Yes | 15.7 | 3.3 | .014 | 16.3 | 23.7 | .450 |

| No | 78.7 | 81.7 | 71.5 | 68.4 | ||

| Unsure | 5.6 | 15.0 | 12.2 | 7.9 | ||

| Previous PSA test*(%) |

||||||

| Yes | 37.1 | 22.0 | .047 | 74.5 | 50.0 | .007 |

| No | 43.8 | 64.4 | 14.3 | 26.3 | ||

| Unsure | 19.1 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 23.7 | ||

| Education*(%) | ||||||

| < High school | 27.0 | 30.5 | .892 | 3.4 | 2.6 | .642 |

| High school graduate | 43.8 | 42.4 | 6.5 | 10.5 | ||

| > High school | 29.2 | 27.1 | 90.1 | 86.8 | ||

Indicates significant differences between patients at the low-literacy and high-literacy sites at the 2-week follow-up (P<.001).

SD, standard deviation; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

3.2. Acceptability of Decision Aids

Table 3 summarizes subjects’ responses to the acceptability measures completed after exposure to the decision aids. For the entertainment-based aid, subjects from the low-literacy site were more likely to rate the program as having too much information and were less likely to rate the program as too long when compared to subjects at the high-literacy site. More subjects at the high-literacy site considered the materials to be completely clear when compared to subjects at the low-literacy site. A similar pattern was observed for the amount and length acceptability measures among subjects who received the audiobooklet. Ratings of clarity did not differ between the study sites for subjects who received the audiobooklet, and there was a suggestion of minor differences between the subjects at both sites on ratings of program balance. Finally, when only subjects from the low literacy site were considered, the clarity of the audiobooklet was rated higher than the clarity of the entertainment aid (χ2 (3) = 9.75, P<.05). Yet, over 90% of low literacy site subjects indicated that most or everything was clearly presented, regardless of the aid received.

Table 3.

Decision Aid Acceptability Measures.

| Entertainment Aid | Audiobooklet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Literacy Site |

High- Literacy Site |

P- Value |

Low- Literacy Site |

High- Literacy Site |

P-Value | |

| (n=65) | (n=148) | (n=70) | (n=153) | |||

| Amount of information (%) | ||||||

| Less than wanted | 9.2 | 5.4 | 10.0 | 7.2 | ||

| About right | 50.8 | 85.8 | 0.00 | 58.6 | 85.6 | 0.00 |

| More than wanted | 40.0 | 8.8 | 31.4 | 7.2 | ||

| Program length (%) | ||||||

| Too long | 10.8 | 42.6 | 2.9 | 5.3 | ||

| About right | 75.4 | 56.1 | 0.00 | 75.7 | 90.1 | 0.00 |

| Should be longer | 13.8 | 1.4 | 21.4 | 4.6 | ||

| Clarity of presentation (%) | ||||||

| Everything clear | 52.3 | 70.9 | 74.3 | 76.5 | ||

| Most things clear | 40.0 | 25.7 | 21.4 | 21.6 | ||

| Some things clear | 4.6 | 2.7 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.21 |

| Most things unclear | 3.1 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 0.7 | ||

| Balance of program (%) | ||||||

| Slanted to favor screening | 49.2 | 58.8 | 44.9 | 54.9 | ||

| Completely balanced | 46.2 | 39.9 | 0.20 | 47.8 | 45.1 | 0.01 |

| Slanted to favor no screening | 4.6 | 1.4 | 7.2 | 0.0 | ||

P-values were calculated from chi-square tests.

More than 90% of subjects who completed the entertainment-based aid rated the program helpful, would recommend the program to others, and wanted similar programs. Subjects from the low-literacy site were more likely to have wanted to ask questions about the program content (66.7% vs. 25.7%; P<0.001) than were subjects from the high-literacy site.

3.3. Engagement with the Entertainment-Based Aid

Responses to the engagement questions for subjects assigned to the entertainment-based aid are given in Table 4. Patients from the low-literacy site reported greater engagement with the soap-operatic segments, the values-clarification exercise, and the celebrity testimonials when compared to patients from the high-literacy site.

Table 4.

Engagement Scale* Scores for Low-Literacy and High-Literacy Subjects Who Completed the Entertainment-Education Decision Aid.

| Engagement Scales | Low- Literacy Site (n=64) |

High- Literacy Site (n=146) |

F-ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|||

| General Scale | 69.3 (31.3) |

66.3 (29.1) |

0.44 | 0.510 |

| Soap Opera Scale | 90.2 (15.5) |

80.3 (23.2) |

9.61 | 0.002 |

| Values Scale | 97.7 (7.8) |

80.9 (29.9) |

19.40 | 0.000 |

| Testimonials Scale | 96.1 (12.2) |

87.9 (22.0) |

7.81 | 0.006 |

Two subjects from the low-literacy site and two from the high literacy site had incomplete responses to the engagement questions, and were dropped from this analysis.

Uses a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating greater engagement with the program.

SD, standard deviation.

3.4. Change in Knowledge

Overall, subjects from the low-literacy site had lower knowledge scores than did subjects from the high-literacy site. Nevertheless, subjects from both sites had significant improvements in knowledge—regardless of the decision aid they received—and there were no significant differences between the aids in subjects’ knowledge gains.

3.5. Decisional Conflict

Findings of decisional conflict are reported separately by site because a low-literacy version of the DCS was used at the low-literacy site (Table 5). At the 2-week follow-up, subjects from the low-literacy site who received the entertainment-based aid felt clearer about their personal values relative to the screening decision (values subscale), and were less conflicted overall about the screening decision (total scale) when compared to subjects who received the audiobooklet. The analysis comparing subjects who received the entertainment-based aid and those who received the audiobooklet on feeling more informed (informed subscale) about the decision and its benefits and risks did not reach statistical significance. For subjects at the high-literacy site, there were no differences on the DCS between those who received the entertainment-based aid and those who received the audiobooklet.

Table 5.

Decisional Conflict Scale Scores at the 2-Week Follow-up for Both Intervention Groups at Both Study Sites.

| Low-Literacy Site* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | EE Intervention | Audiobooklet |

P- Value |

||

| n | Mean†(95% CI) | n | Mean†(95% CI) | ||

| Uncertainty | 39 | 5.8 (0.1–11.4) | 48 | 6.8 (1.7–11.9) | 0.80 |

| Informed | 39 | 9.1 (0.9–17.2) | 46 | 18.8 (11.2–26.3) | 0.09 |

| Values | 40 | 17.4 (6.0–28.8) | 48 | 34.9 (24.6–45.3) | 0.03 |

| Social Support | 39 | 17.8 (8.5–27.1) | 48 | 27.6 (19.2–35.9) | 0.12 |

| Total | 38 | 12.0 (5.0–18.9) | 46 | 21.7 (15.4–28.0) | 0.04 |

| High-Literacy Site* | |||||

| Scale | EE Intervention | Audiobooklet |

P- value |

||

| n | Mean†(95% CI) | n | Mean†(95% CI) | ||

| Uncertainty | 120 | 14.3 (11.8–16.7) | 136 | 16.5 (14.1–18.8) | 0.20 |

| Informed | 116 | 10.2 (7.5–12.9) | 138 | 10.3 (7.8–12.8) | 0.96 |

| Values | 117 | 16.4 (13.4–19.5) | 136 | 18.6 (15.8–21.5) | 0.30 |

| Social Support | 119 | 15.8 (12.9–18.7) | 137 | 16.0 (13.3–18.7) | 0.93 |

| Effective Decision | 120 | 11.0 (8.7–13.3) | 137 | 12.7 (10.5–14.8) | 0.30 |

| Total | 108 | 12.7 (10.4–15.0) | 131 | 15.0 (12.9–17.1) | 0.15 |

The low-literacy version of the Decisional Conflict Scale (includes only 4 scales) was used for the low health literacy site, and the traditional version was used for high health literacy site. Because the versions are different, the scores derived from them should not be compared across the study sites.

Means are adjusted for baseline scores on the Decisional Conflict Scale. Higher scores indicate greater decisional conflict.

95% CI, the 95% confidence interval for the mean; EE, entertainment education.

3.6. Self-Advocacy

Findings about self-advocacy are reported separately by site because a low-literacy adaptation of the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale was used at the low-literacy site (Table 6). At the low-literacy site, subjects who received the entertainment-based aid reported being more willing and having greater ability to obtain educational information about screening than did those who received the audiobooklet. There were no differences between the decision-aid groups in subjects’ assertiveness with their doctors or the potential for mindful nonadherence. Finally, there were no differences in self-advocacy scores among the subjects at the high-literacy site based on the decision aid received.

Table 6.

Patient Self-Advocacy Scale Scores at the 2-Week Follow-up for Both Intervention Groups at Both Study Sites.

| Low-Literacy Site* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | EE Intervention | Audiobooklet |

P- Value |

||

| n | Mean†(95% CI) | n | Mean†(95% CI) | ||

| Illness and Treatment |

39 | 1.45 (1.30–1.61) | 49 | 1.69 (1.55–1.83) | 0.03 |

| Education Assertiveness |

40 | 1.50 (1.36–1.64) | 49 | 1.55 (1.42–1.68) | 0.61 |

| Non-adherence | 40 | 2.03 (1.86–2.21) | 48 | 2.03 (1.87–2.19) | 0.97 |

| Total | 39 | 1.66 (1.56–1.76) | 48 | 1.75 (1.67–1.84) | 0.15 |

| High-Literacy Site* | |||||

| Scale | EE Intervention |

Audiobooklet |

P- Value |

||

| n | Mean†(95% CI) | n | Mean†(95% CI) | ||

| Illness and Treatment |

122 | 2.02 (1.92–2.11) | 135 | 1.97 (1.88–2.06) | 0.52 |

| Education Assertiveness |

119 | 2.15 (2.06–2.24) | 136 | 2.25 (2.16–2.33) | 0.12 |

| Non-adherence | 119 | 3.03 (2.93–3.14) | 134 | 3.12 (3.02–3.22) | 0.24 |

| Total | 116 | 2.41 (2.34–2.47) | 126 | 2.45 (2.39–2.47) | 0.38 |

The low-literacy adaptation of the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale (includes only four scales) was used at the low health literacy site, and the original version was used at the high health literacy site.

Means are adjusted for baseline scores on the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale. Lower scores indicate greater self-advocacy.

95% CI, the 95% confidence interval for the mean; EE, entertainment education.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

This study evaluated a promising approach for delivering decision support to patients with low health literacy. Only a few studies have used entertainment education as a model for delivery of decision support to patients facing conditions of uncertainly [20,21]. We evaluated an entertainment-based decision aid among patients with low health literacy at a county health clinic and with high health literacy at a university-affiliated clinic. The control condition was an audiobooklet decision aid lacking the entertainment component, providing a worthy comparison to the entertainment aid beyond a no-intervention control.

The acceptability measures offer an interesting picture of both decision aids. Among patients who received the entertainment-based aid, those at the low-literacy site were more likely to have wanted additional information, and those at the high-literacy site were more likely to rate the program as too lengthy.

These findings have several implications for how decision aids might be used clinically. Patients with higher health literacy may be more interested in learning the key facts needed to make a decision and in receiving this information quickly. In contrast, patients with lower health literacy appear to enjoy the additional, engaging components and are less concerned about program length. However, many patients find the information to be overly extensive, which suggests that alternative approaches for delivering decision support may be needed. For example, exposing patients to the aid over several office visits or before an office visit to allow self-paced learning may be important modifications for low-literacy patients.

Gains in knowledge were the same at both study sites, no matter which decision aid was used. This finding is not surprising, because the two aids contained the same factual content. Apparently, the multimedia entertainment-based aid offers no advantage over the audiobooklet in educating patients about the key facts regarding prostate cancer, screening, and treatment.

Differences between the aids in decisional conflict were only evident among the low-literacy patients. Regardless of the aid received, low-literacy patients were clear about which choice was best for them, which is consistent with the general public’s enthusiasm about early detection of cancer [31]. Moreover, low-literacy patients who received the entertainment-based aid had less decisional conflict and were clearer about those factors related to the decision to be screened that were most important to them. This latter finding is particularly interesting, because the entertainment-based aid included an explicit values-clarification component structured as a social-matching exercise. Further support of the importance of this component comes from the engagement measures which showed that low-literacy patients were more engaged with the social-matching exercise than were high-literacy patients. Although there have been recent criticisms of explicit values-clarification exercises in patient decision aids [32], our findings suggest that the use of these techniques may have a favorable impact on decision-making outcomes for patients with lower health literacy and that additional investigation is warranted.

Low-literacy patients who received the entertainment-based aid had higher scores on the self-advocacy measures than did patients who received the audiobooklet. In particular, low-literacy patients who viewed the entertainment-based aid felt they were more educated about prostate cancer screening and said they would actively seek out information. This finding is encouraging in light of the goals for informed decision-making and for helping patients to become greater advocates for their own care [29]. However, there were no differences between the assertiveness and mindful nonadherence measures for either literacy group or for either decision aid. This finding is not surprising given the extensive literature demonstrating that less education is associated with greater preference to defer authority in decision making [33].

4.2 Limitations

This study has a number of noteworthy limitations. The study was conducted in two clinical sites, one public and one private, limiting its generalizability. The follow-up rate for patients at the low-literacy site was about 60%, and patients from both sites who completed the 2-week follow-up appeared to be more interested in or favorable toward screening. The higher rate of loss to follow-up among subjects from the low literacy site was not unexpected. It can be difficult to maintain up-to-date contact information with this population, even over short follow-up periods. Patients who completed the follow-up were older and more interested in prostate cancer screening than patients who did not complete the follow-up, perhaps leading to stronger effects for the low literacy site subjects than might have been observed otherwise.

While the aids had the same factual content, the entertainment-based aid was longer due to the added features. The study design did not allow for examining which combinations of features (e.g., soap opera segments, testimonials) were most strongly related to the outcomes. Despite the neutral messages, we recognize that some subjects may interpret the participation of a celebrity in the aid as an endorsement of screening. There was no direct assessment of literacy levels for individual patients; rather, literacy was inferred based on the clinical setting and characteristics of the samples. In clinical practice, assessing literacy levels of individual patients may not be feasible and increase stigmatization of patients [34]. Assessing health literacy of individual patients is not consistent with recommendations for universal precautions, where the goal is to reduce the health literacy demands made upon all patients [34]. Finally, the influence of some other factor in explaining the differences across sites cannot be ruled out.

4.2. Conclusion

The use of interactive, multimedia decision aids for prostate cancer screening with an entertainment-education component holds great promise for involving patients with low health literacy in decision making. Patients appear to be engaged with the experience, are clearer about how their values affect their preferences, and feel more empowered about their ability to find and master information. Entertainment education may be a powerful strategy for delivering decision support to a large segment of the population with low health literacy.

4.3. Practice Implications

Questions remain about the implementation of prostate cancer screening decision aids in routine clinical practice. As with all patient decision aids, uptake in clinical practice remains very low [35]. The aids may also be too long for delivery in the clinical setting immediately before an office visit. Alternative models for delivering patient decision support need to be explored as barriers to accessing technology decrease.

Acknowledgements

The Acceptability and DCS are copyrighted by the Ottawa Health Decision Centre at the Ottawa Health Research Institute. We want to thank Viola Benavidez and Smita Saraykar for their help in collecting the data for this study. We also thank Pamela Paradis Metoyer, ELS(D) for providing editorial expertise for the manuscript.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. 5 R01 HS10612) and the National Cancer Institute (grant no. R25CA057712, awarded to Suzanne Kneuper). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no involvement in the design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix

Appendix.

Summary of Content from Learning Modules from Decision Aid “Making Informed Decisions about Testing for Prostate Cancer.”

| Topic Area | Messages |

|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer Facts | The decision to be tested for prostate cancer is not easy, because testing can lead to a new series of decisions a man must make, the results of which can change his life in both beneficial and not so beneficial ways. This program has been designed to help in making these important decisions. Concerning this emotional subject, most doctors and professional medical groups agree that being well informed about the pros and cons of testing and treatment is essential in making a decision about being tested. |

| Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men and is the second leading cause of cancer deaths. | |

| The cancer cells can spread to the bones and lungs, and eventually lead to death. | |

| Most prostate cancers grow slowly. More men die with prostate cancer than of prostate cancer. For many men, they never know they have prostate cancer. | |

| Prostate Cancer Risk | As a man ages, his risk goes up. Most cancers are found in men over the age of 65, and are less common in men under 50. |

| African American men and those with a blood relative who had prostate cancer have the highest risk. | |

| Testing for Prostate Cancer | Finding the cancer early may make it more likely that the man can be cured. |

| Both the PSA and Digital Rectal Exam should be used for testing. | |

| Testing is not perfect and can lead to unnecessary biopsies. Sometimes cancer is present and the test misses it. | |

| Treatment for Prostate Cancer | There are several effective treatments for prostate cancer. |

| Factors like a man’s age, stage and grade of tumor, and his general health determine what his treatment options are. | |

| For some men, usually older men, watching and waiting is a treatment option. | |

| Treatment Complications for Prostate Cancer | Treatment has important side effects, including impotence, incontinence, and bowel problems. |

Core content was the same for the Entertainment and Audiobooklet decision aids.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Contributor Information

Robert J. Volk, Department of Family and Community Medicine, and Houston Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics, Baylor College of Medicine, Address: 3701 Kirby, Suite 600, Houston, Texas 77098-3915, Telephone: 713-798-1660, Fax: 713-798-7940, E-mail:bvolk@bcm.edu

Maria L. Jibaja-Weiss, Department of Family and Community Medicine, and Houston Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics, Baylor College of Medicine

Sarah T. Hawley, Division of General Medicine, Ann Arbor VAMC, University of Michigan

Suzanne Kneuper, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine.

Stephen J. Spann, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine

Brian J. Miles, Scott Department of Urology, Baylor College of Medicine

David J. Hyman, Department of Family and Community Medicine and Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine

References

- 1.American Urological Association (AUA) Oncology. Vol. 14. Williston Park: 2000. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) best practice policy; pp. 267–272.pp. 77–78. 80 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for prostate cancer: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:917–929. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:41–52. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M, Tetroe J, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Entwistle V, Rostom A, Fiset V, Barry M, Jones J. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Oxford, UK: The Cochrane Library; 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volk RJ, Hawley ST, Kneuper S, Holden EW, Stroud LA, Cooper CP, Berkowitz JM, Scholl LE, Saraykar SS, Pavlik VN. Trials of decision AIDS for prostate cancer screening: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagerlin A, Rovner D, Stableford S, Jentoft C, Wei JT, Holmes-Rovner M. Patient education materials about the treatment of early-stage prostate cancer: a critical review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:721–728. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-9-200405040-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes-Rovner M, Stableford S, Fagerlin A, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Ohene-Frempong J, Kelley-Balke K, Rovner DR. Evidence-based patient choice: a prostate cancer decision aid in plain language. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Panzer AM, Hamlin B, Kindig DA. Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academics Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ. Utilizing computerized entertainment education in the development of decision AIDS for lower literate and naive computer users. J Health Commun. 2007;12:681–697. doi: 10.1080/10810730701624356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nariman HN. Soap operas for social change - toward a methodology for entertainment-education television. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-education - a communication strategy for social change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singhal A, Rogers EM. A theoretical agenda for entertainment-education. Communication Theory. 2002;12:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herczeg M. Experience design for computer-based learning systems: Learning with engagement and emotions. ED-MEDIA 2004 World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications; Lugano, Switzerland. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: a review of the literature. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1999;6:272–282. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strecher VJ, Greenwood T, Wang C, Dumont D. Interactive multimedia and risk communication. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1999;25:134–139. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawless K, Gerber B, Smolin L. Diabetes and your eyes: a pilot study on multimedia education for underserved populations. ED-MEDIA 2004 World Conference on Education Materials, Hypermedia and Telecommunications; Lugano, Switzerland. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC. The contributions of health communication to eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2053–2055. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoki N, Ohta S, Okada T, Oishi M, Fukui T. INSULOT: a cellular phone-based edutainment learning tool for children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Friedman LC, Granchi TS, Neff NE, Spann SJ, Robinson EK, Aoki N, Beck JR. Preliminary testing of a just-in-time, user-defined values clarification exercise to aid lower literate women in making informed breast cancer treatment decisions. Health Expect. 2006;9:218–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jibaja-Weiss ML, Volk RJ, Granch TS, Nefe NE, Spann SJ, Aoki N, Beck JR. Entertainment education for informed breast cancer treatment decisions in low-literate women: development and initial evaluation of a patient decision aid. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:133–139. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2103_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood, CA: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor AM. User manual for acceptability: Ottawa Health Decision Centre at the Ottawa Health Research Institute. University of Ottawa; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cin SD, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Narrative persuasion and overcoming resistance. In: Knowles ES, Linn JA, editors. Resistance and persuasion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Dell KJ, Volk RJ, Cass AR, Spann SJ. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen test: are patients making informed decisions? J Fam Pract. 1999;48:682–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janis IL, Mann L. Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. New York: Free Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor AM. Decisional conflict scale. 4th edition. Ottawa Health Decision Centre at the Ottawa Health Research Institute (University of Ottawa); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor AM. User manual - decisional conflict scale(s): Ottawa Health Decision Centre at the Ottawa Health Research Institute. University of Ottawa; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B, Coates RC, Lee NC, Mullen P, Corso P, Hutchinson AAB, Hiatt R, Kerner J, George P, White C, Gandhi N, Saraiya M, Breslow R, Isham G, Teutsch SM, Hinman AR, Lawrence R. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brashers DE, Haas SM, Neidig JL. The patient self-advocacy scale: measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Commun. 1999;11:97–121. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. J Amer Med Assoc. 2004;2911:71–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson WL, Han PK, Fagerlin A, Stefanek M, Ubel PA. Rethinking the objectives of decision aids: a call for conceptual clarity. Med Decis Making. 2007;27:609–618. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07306780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients' preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham ID, Logan J, O'Connor A, Weeks KE, Aaron S, Cranney A, Dales R, Elmslie T, Hebert P, Jolly E, Laupacis A, Mitchell S, Tugwell P. A qualitative study of physicians' perceptions of three decision aids. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]