Abstract

A-kinase (PKA) anchoring proteins (AKAPs) are essential for targeting type II PKA to specific locales in the cell to control function. In the present study, AKAP5 (formerly AKAP150) and AKAP6 were identified in mouse parotid acini by type II PKA regulatory subunit (RII) overlay assay and Western blot analysis of mouse parotid cellular fractions, and the role of AKAP5 in mouse parotid acinar cell secretion was determined. Mice were euthanized with CO2. Immunofluorescence staining of acinar cells localized AKAP5 to the basolateral membrane, whereas AKAP6 was associated with the perinuclear region. In functional studies, amylase secretion from acinar cells of AKAP5 mutant [knockout (KO)] mice treated with the β-adrenergic agonist, isoproterenol, was reduced overall by 30–40% compared with wild-type (WT) mice. In contrast, amylase secretion in response to the adenylyl cyclase (AC) activator, forskolin, and the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) activator, N6-phenyl-cAMP, was not statistically different in acini from WT and AKAP5 KO mice. Treatment of acini with isoproterenol mimicked the effect of the Epac activator, 8-(4-methoxyphenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP), in stimulating Rap1. However, in contrast to isoproterenol, treatment of acini with 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP resulted in stimulation of amylase secretion from both AKAP5 KO and WT acinar cells. As a scaffolding protein, AKAP5 was found to coimmunoprecipitate with AC6, but not AC8. Data suggest that isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion occurs via both an AKAP5/AC6/PKA complex and a PKA-independent, Epac pathway in mouse parotid acini.

Keywords: A-kinase anchoring protein 5; knockout mice; isoproterenol; Epac; 8-(4-methoxyphenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; Rap1

salivary protein secretion from parotid acinar cells, which imparts digestive, antimicrobial, and lubricating functions of saliva, is known to be regulated mainly by the cAMP signaling pathway in rat parotid acinar cells (17) and by both cAMP and calcium signaling pathways in mouse parotid cells (51). β-Adrenergic receptor stimulation was shown to cause cAMP-dependent protein secretion in the parotid gland via the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) (47). As a holoenzyme, PKA is composed of two catalytic subunits and a regulatory dimer in the absence of cAMP (46). Two known isoenzymes of PKA, type I PKA (PKA-I) and type II PKA (PKA-II), have been identified in rat parotid acini (28, 29). The binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunits leads to the disassociation of the free, active catalytic subunits to phosphorylate variable PKA substrates in parotid acini, including unidentified substrates in the apical actin network, secretory granule, and plasma membrane (17, 28, 29, 36).

The restricted localization of PKA can be explained by the association between regulatory subunits of PKA and the recent discovery of A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). To date, about 70 different AKAPs have been identified (53), and the number of this protein family is still expanding. Most AKAPs bind to PKA-II, while dual-specific AKAPs are capable of binding to both types of PKA (53). A limited number of AKAPs are also reported to bind to PKA-I only (25, 27). AKAPs are adaptor proteins that serve as bridges between PKA, substrates of PKA, and variable subcellular organelles, via domains that bind to PKA and to specific subcellular organelles, including the nucleus, the Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and actin cytoskeleton in the cell (53). The ability of AKAPs to bind to kinases other than PKAs, protein phosphatases, phosphodiesterases, receptors, and ion channels also leads to integration of different signaling pathways in these scaffolding proteins (53).

A role for AKAPs in protein secretion in different cell types was established using peptides that disrupt the association between PKA and AKAP. Expression of Ht-31, a peptide that displaces PKA from AKAP in clonal RINm5F cells, abrogated cAMP-stimulated insulin secretion (26). Treatment of cells with biotinylated Ht-31 in lipofectamine-permeabilized primary rat pancreatic islets blocked glucagon-like peptide-1-mediated insulin secretion (26). Glucagon-induced insulin release from INS-1 cells was also eliminated by TAT-AKAPis, another AKAP inhibitor (15). In guinea pig chief cells, cAMP-dependent pepsinogen secretion was reduced by 32% in the presence of the cell-permeable form of Ht-31 (54). On the basis of these studies, it appeared feasible to determine the involvement of AKAPs in cAMP/PKA-mediated events. However, peptides disrupting the association between AKAPs and PKA may not be useful for identifying the role of a specific AKAP in protein secretion, since multiple AKAPs are likely expressed in secretory cells. Studies show that AKAP8 (formerly AKAP95) and AKAP5 (AKAP79/150) are expressed in rat parotid acini (24) and that ezrin is expressed in mouse parotid acini (2). Thus, experiments performed with cells isolated from AKAP knockout (KO) mice, or cells in which dominant-negative mutants or small interfering RNA are introduced, would be helpful in clarifying the role of AKAPs in physiological processes.

In the present study, we determined the expression of AKAPs in mouse parotid acinar cells and the role of AKAP5 in secretion. We report that mouse parotid acini express AKAP5, which is involved in isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion in mouse parotid acini. Data further suggest that isoproterenol stimulates secretion via a secondary pathway involving Epac, a guanine nucleotide exchange protein activated directly by cAMP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Materials were obtained as follows: collagenase (lot 12794922) from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany); hyaluronidase, l-glutamine, BSA (faction V), and cAMP agarose from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); isoproterenol from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); N6-phenyl-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (6-Phe-cAMP) and 8-(4-methoxyphenylthio)-2′-O-methyl-adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP) from Biolog Life Science Institute (Bremen, Germany); forskolin from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA); recombinant rat type II PKA regulatory β-subunits (RIIβ) from Alexis Biochemicals(Lausen, Switzerland); St-Ht31 from Promega (Madison, WI); goat anti-AKAP5 (C-20), anti-PKARIIβ (M-18) subunit, and adenylyl cyclase (AC) antibodies (AC6, C-17; AC8, R-20) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); goat anti-AKAP6 from Imgenex (San Diego, CA); Rap1 activation assay kit from Upstate (Millipore, Billerica, MA); ChromPure IgG and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA); Alexa Fluor (AF) dye-conjugated secondary antibodies, phalloidin, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); and Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western Blotting System from GE Healthcare, Amersham Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA). Rabbit serum against AKAP6, VO145, was a generous gift from John Scott (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Pharmacology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Rabbit anti-AKAP5 polyclonal antibody, 1889J, was kindly gifted by Dr. Yvonne Lai (ICOS, Bothell, WA).

Preparation of parotid acini.

AKAP5 KO mutant mice (20) and wild-type (WT) mice, strain C57BL/6, were bred from heterozygous mating. Genotyping of animals was performed by amplifying AKAP5 or a neomycin cassette from tail genomic DNA. For the AKAP5 PCR, the forward primer was 5′-GGC CTT GTG ACA CAC AGG AA-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-CAG GCG GCT TCT GCT TCT T-3′. The forward primer for the neomycin PCR was 5′-ATG GCC GCT TTT CTG GAT T-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-GCC AAG CTC TTC AGC AAT ATC A-3′.

KO and WT mice were euthanized under an atmosphere of CO2 before cervical dislocation, using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol no. 2133-01) for tissue and parotid acinar cell preparation. Small aggregates of parotid acinar cells were prepared as described previously (42). Briefly, parotid glands from male mice (20–30 g) were removed and minced in Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate buffer (KHB) containing purified 0.08 mg/ml collagenase, 0.025 mg/ml hyaluronidase, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 0.1% BSA. Enzyme digestion was performed at 37°C for 60 min under continuous 5% CO2-95% O2 gassing. The cell suspension was dispersed by gently pipetting 12 times after incubation at 30, 40, 50, and 55 min, and 5 times at 60 min. Cells were washed, filtered, and rested in 1% BSA in KHB for 30 min at 37°C with continuous gassing before use.

Preparation of cellular fractions from mouse parotid acini.

Acini were collected for preparation of soluble and particulate fractions from a 10% (wt/vol) suspension of acinar cells in ice-cold homogenate buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and the protease inhibitor cocktail (1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.7 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 0.2 mM PMSF), as described by Watson et al. (50). Cell homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000 g at 4°C for 1 h to yield the particulate membrane fraction. ER and nuclear membranes were prepared from cells homogenized in isotonic mannitol buffer (290 mM mannitol, 10 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2) and centrifuged at 1,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was used to prepare ER membranes as described previously by Ozawa and Nishiyama (35). The 1,000-g pellet was solubilized in ice-cold TKM buffer [1.67 M sucrose in 5 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), KCl 25 mM, and MgCl2 5 mM] and used to prepare nuclear membranes as described by Nakagawa et al. (32). Cytoskeletal components were prepared from a 10% suspended cells in Triton extraction buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris·HCl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM EGTA), as described by Burgoyne et al. (8) and Fischer et al. (16) with modification. The cytoskeleton fraction was collected by centrifugation of cell homogenates at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The 10,000-g supernatant was further centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C to yield the membrane skeletal fraction. Control tissues, including mouse brain and mouse heart, were prepared as described above for parotid acini.

Cyclic AMP agarose affinity pull-down assay and immunoprecipitation.

Cyclic AMP-binding proteins were isolated and purified from mouse parotid acini, using a cAMP agarose affinity pull-down assay described by Raymond et al. (38). Briefly, cells suspended in ice-cold buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM DTT, and 10 μM IBMX were homogenized and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Cell lysate supernatant (2 mg) was cleared with protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and incubated with cAMP agarose overnight at 4°C.

For immunoprecipitation experiments, parotid acini obtained from AKAP5 KO mice and the WT strain were lysed on ice with RIPA buffer, pH 7.2 (1× PBS, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris·HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and the protease inhibitor cocktail). Lysate proteins (250–500 μg) were precleared for 30 min at 4°C with 1 μg of control IgG and 20 μl of protein A/G agarose and incubated with 4 μg of AKAP5 antibody at 4°C for 4 h, followed by a 20-μl addition of resuspended protein A/G agarose for an additional 2 h of incubation. Agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min and solubilized in 40–60 μl of 1:1 ratio of NuPAGE LDS sample buffer and NuPAGE reducing buffer (Invitrogen).

Immunoblot analysis and RII overlay assay.

Solubilized proteins of cell lysates, cellular fractions, cAMP-binding proteins, and immunoprecipitates were coresolved with proteins of standard molecular weight on SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (Invitrogen) membrane (49). Filters were blocked with 1% IgG-free, protease-free BSA (Jackson ImmunoResearch), 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 1% polyethylene glycol in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (T-TBS). For the RII overlay assay, after blocking, filters were incubated with 5 nM of recombinant RIIβ subunits in the presence or absence of 2 μM St-Ht31 in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. Cellular proteins not binding to recombinant rat RIIβ in the presence of 2 μM St-Ht31 were considered as AKAPs. Immunoblot analysis was performed using antibodies to detect rat RIIβ (0.4 μg/ml in 0.1% T-TBS), endogenous AKAP5 (0.4 μg/ml), AKAP6 (0.5 μg/ml), AC6 (2 μg/ml), or AC8 (0.2 μg/ml), with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:20,000). The signal was detected by ECL Western Blotting System. The molecular weight of a specific protein was determined by plotting its mobility against standard proteins of known molecular weight on a logarithmic scale using the FragmeNT Analysis v1.2 software (GE Healthcare UK).

Immunocytofluorescence analysis.

Isolated mouse parotid acinar cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and blocked with 1% BSA and 0.1% gelatin for 1 h at room temperature. AKAPs were labeled by an overnight incubation with goat anti-AKAP5 antibody (diluted 1:100 in 0.1% BSA) or rabbit anti-AKAP6 antiserum at 4°C overnight, followed by a 1-h incubation with AF dye-coupled secondary antibody (1:2,000). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Stained acinar cells were fixed on poly-l-lysine-coated slides, observed with ×60 objective of a Zeiss LSM 510 META laser-scanning microscope at the Keck imaging Center (University of Washington, Seattle). Images of fluorescence intensity were collected by Zeiss LSM 510 software and transferred to readable TIFF files by Zeiss LSM Image Browser.

Amylase secretion.

After resting, acinar cells were treated with appropriate pharmacologic agents or the carrier control in KHB containing 0.1% BSA and no added CaCl2 and placed in a rotary water bath at 37°C for 20 min. Amylase secreted from acinar cells was reported as a percentage of total amylase. To obtain total amylase before stimulation, an aliquot of cells was lysed by 0.2% Triton X-100. Amylase activity was measured by the method of Bernfeld (4).

Rap1 activity assay.

Activation of Rap1 was determined by affinity purification of GTP-Rap1 with Ral GDS-RBD agarose using reagents and protocol of the Rap1 Activation Assay Kit from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY) modified to include 2 mM activated sodium orthovanadate, 25 mM sodium fluoride in lysis, and wash buffers. Concomitantly, acinar cell lysates were incubated with GDP and GTPγS per kit protocol to obtain negative and positive Rap1-GTP controls, respectively. Total Rap1 of cell lysates used for GTP-Rap1 was performed to normalize Rap1 activation results.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in agonist-stimulated amylase secretion from AKAP5 KO and WT mice were tested for significance using multivariate analysis of variance and F-statistic at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

AKAPs identified in mouse parotid acini by RII overlay assay and immunoblot analyses.

To date, the expression of AKAPs in mouse parotid acini has not been reported. Thus, to identify AKAPs in parotid acini, we performed an RII overlay assay. As shown in Fig. 1A, seventeen putative AKAPs with a molecular mass between 40 kDa and 500 kDa were identified in cellular fractions prepared from total cell and cAMP agarose affinity precipitates of mouse parotid acinar cell lysates. The majority of proteins did not bind RII in the presence of St-Ht31, which competed with the binding of RII with the resolved cellular AKAPs transferred to the membrane, while the signal intensity of a few was reduced by more than 60% (Fig. 1A, right). Blot intensities of two AKAPs were reduced by St-Ht31 (a and b in Fig. 1A), coinciding with AKAP5 and AKAP6, which were identified by immunoblot analyses (Fig. 1, B and C). AKAP5 was enriched in the particulate membrane fraction as well as the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1B). An antibody against AKAP6 detected a protein of 290 kDa, which was most abundant in the nuclear membrane isolated from mouse parotid acini (Fig. 1C). A protein of ∼220 kDa, enriched in ER of mouse parotid acini, was also detected (Fig. 1C). Since the molecular weight of this protein is smaller than the reported molecular weight of AKAP6 (30), this protein is likely to be the degradation product of the 290-kDa AKAP6.

Fig. 1.

A: identification of A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) in mouse parotid acini by type II PKA regulatory subunit (RII) overlay assay of cellular fractions enriched in cytoskeleton (Ck), membrane skeleton (Msk), soluble fraction (Sn), and cAMP pull-down isolates (PD), in the absence and presence of St-Ht31 (50 μM). Intracellular proteins that are likely to be AKAPs are indicated by arrows. Among these proteins, a and b were identified as AKAP6 (a) and AKAP5 (b), respectively, by Western blot analyses. B: identification of AKAP5 by Western blot analyses in cell lysates isolated from parotid acini (MP) of AKAP5 knockout (KO) mice and its wild-type strain (WT). Cellular fractions of acinar cells obtained from WT mice, including nuclear membranes (N), particulate membranes (PM), the soluble fraction (S), cytoskeleton, membrane skeleton, and the soluble fraction not containing cytoskeleton and membrane skeleton, were also subjected to Western blot identification of AKAP5. Mouse brain (MB) of the WT strain served as the control tissue. C: AKAP6 and its protein degradation products (*) were identified by Western blot analyses of cellular fractions collected from mouse parotid acini, including the nuclear membrane, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the soluble fraction, and the membrane fraction which excluded the N and ER (M). Cellular proteins were also extracted from mouse heart (MH), which served as the control tissue.

Immunofluorescent localization of AKAP5 and AKAP6 in mouse parotid acini.

AKAP5 and AKAP6 were localized in mouse parotid acinar cells by immunofluorescent confocal microscopy using specific AKAP5 and AKAP6 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 2, AKAP5 was primarily localized to the plasma membrane of the cells. Actin labeled with AF-conjugated phalloidin was known to be most prominent in the apical region (34) and was not colocalized with AKAP5. In contrast to AKAP5, cells stained with rabbit AKAP6 antiserum showed fluorescent signals concentrated around nuclei, which were stained with DAPI, in some parotid acini, but not all (Fig. 3). This finding is consistent with the detection of a 290-kDa protein in the nuclear membrane-enriched fraction by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescent localization of AKAP5 in mouse parotid acini. A: acinar cells were incubated with a goat AKAP5 antibody followed by an Alexa Fluor (AF) 488-conjugated secondary antibody to label AKAP5 (green). B: actin cytoskeleton was stained with AF555-conjugated phalloidin (red). C: nuclei were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). D: images were merged to show that AKAP5 is most abundant in the plasma membrane.

Fig. 3.

Immunofluorescent localization of AKAP6 in mouse parotid acini. A: acinar cells were incubated with rabbit AKAP6 antiserum followed by an AF555-conjugated secondary antibody to label AKAP6 (red). B: nuclei were labeled with DAPI (blue). C: images were merged to show perinuclear localization of AKAP6 in some, but not all acini (arrows).

Association of AKAP5 with AC6.

As a scaffolding protein, AKAP5 was found to interact with AC6 in brain (3) and with AC4 and AC6 in human diploid fibroblasts (39). Since protein sequences of human and rodent homologues of AKAP5 are highly conserved (40), it was possible that AKAP5 is associated with more than one isoform of AC in mouse parotid acini. Thus, immunoprecipitation of AKAP5 was performed to evaluate its association with AC6 and AC8, adenylyl cyclases known to be expressed in mouse parotid acini (50). As shown in Fig. 4, AC6, but not AC8, was detected in AKAP5 immunoprecipitates of WT cells. AC6 was not coimmunoprecipitated with AKAP5 in cells from AKAP5 KO mice, which served as a negative control.

Fig. 4.

Left: Western blot identification of adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6), AC8, and AKAP5 in particulate membranes of parotid acinar cell lysates of WT C57BL6 mice. Middle and right: identification of AC6 in immunoprecipitates of AKAP5 (AKAP5 IP) from acinar cell lysates isolated from WT and KO mice.

Isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion in mouse parotid acini isolated from control and AKAP5 KO mice.

Among two identified AKAPs in mouse parotid acini, AKAP5 is the only AKAP reported to play a role in cAMP-stimulated protein secretion from different cell types (26, 54). Thus, to determine the involvement of AKAP5 in β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated amylase release, experiments were performed using acini obtained from control C57BL/6 and AKAP5 KO mice. We found that amylase activity in acinar cells obtained from wild-type animals was 133.5 ± 10.1 U/mg protein, not statistically different (P > 0.05) from amylase activities in cells of AKAP5 KO mice (132.5 ± 10.3 U/mg protein). For the secretion studies, acini were incubated with varying concentrations of the β-adrenergic agonist, isoproterenol (5–50 nM), for 20 min. Isoproterenol concentrations that stimulated amylase secretion with a linear relationship of concentrations over time were used for the experiment (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, amylase secreted from acini of AKAP5 KO mice, compared with WT mice, was reduced by approximately 30–40% over the range of isoproterenol concentrations tested (P < 0.05). The incomplete abrogation of isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion in AKAP5 KO mice suggested that another/other factors/molecules that are activated by β-adrenergic receptor stimulation, but not directly associated with AKAP5, play a role in secretion. In contrast to the effects of isoproterenol on amylase secretion from acini of AKAP5 KO mice, no significant difference was noted in amylase secretion in response to the AC activator forskolin (3.3 to 10 μM) (Fig. 6A) or the specific PKA activator 6-Phe-cAMP (45–500 μM) (Fig. 6B) over the same 20-min time course.

Fig. 5.

Amylase secretion from mouse parotid acinar cells isolated from AKAP5 WT (■) and KO (□) mice. Acini were incubated in a Ca2+-free 0.1% BSA buffer in the presence of isoproterenol (1–50 nM) for 20 min. Amylase released during isoproterenol incubation was represented as its percentage of total cellular amylase activity. Basal secretions, which refers to amylase release in the presence of the control vehicle, i.e., water, from WT mice and AKAP5 KO mice were 3.7% and 4.7% of total amylase, respectively, and were subtracted from all values. Data represent four independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Fig. 6.

Amylase secretion from mouse parotid acinar cells isolated from WT (■) and AKAP5 KO (□) mice. Acini were incubated in a Ca2+-free buffer containing 0.1% BSA, in the presence of forskolin (3.3–10 μM; A) and N6-phenyl-cAMP (6-Phe-cAMP; 45–500 μM; B) for 20 min. Basal secretion from acini of WT mice and AKAP5 KO mice was subtracted from all values. Data represent three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Isoproterenol-stimulated amylase release in AKAP5 KO mice involves Epac.

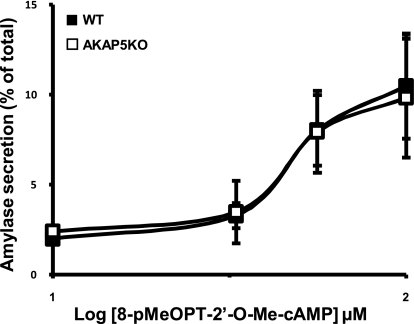

Because isoproterenol-stimulated amylase release was inhibited by 50% in acini from AKAP5 KO mice, data suggested that isoproterenol may stimulate a signaling pathway that is independent of PKA. Recent studies have shown that cAMP, in addition to activating PKA, activates Epac, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that directly activates Rap1 (12). Furthermore, we demonstrated that the translocation of Rap1 is related to isoproterenol-stimulated secretion in rat parotid acini (13). Thus, studies were undertaken to determine whether isoproterenol-stimulated amylase release from mouse parotid acini was, in part, due to the activation of Epac, and consequently, Rap1. For these studies, we first compared the effects of isoproterenol with the Epac activator, 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, on the activation of Rap1 in mouse parotid acini. As shown in Fig. 7, A and B, both 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (100 μM) and isoproterenol (100 nM) stimulated Rap1 in a time-dependent manner. Next, we determined the effects of the Epac activator, 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, on amylase secretion in cells obtained from WT and AKAP5 KO mice. As shown in Fig. 8, 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (10–100 μM) stimulated amylase secretion in both WT and AKAP5 KO cells over a 20-min period; overall differences in secretion between KO and WT cells were not statistically significant.

Fig. 7.

Time-dependent Rap1 activation stimulated by isoproterenol (100 nM; A) and 8-(4-methoxyphenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP; 100 μM; B) in mouse parotid acini. Data are representative of two independent experiments for each agonist.

Fig. 8.

Concentration effects of 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (1–100 μM) on amylase secretion from mouse parotid cells isolated from AKAP5 WT (■) and KO (□) mice. Results are representative of three experiments performed in duplicate.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, we used AKAP5 KO mice to determine the role of AKAP5 in mouse parotid secretion. Data show that AKAP5 is, in part, involved in isoproterenol-stimulated amylase release. Data further suggest that isoproterenol stimulates amylase secretion via a signaling pathway involving Epac. However, the extent to which Epac contributes to isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion was not directly determined. Unfortunately, to date, an inhibitor of Epac is not currently available.

In mouse parotid acini, data show a restricted distribution of AKAPs. AKAP5 was associated with the plasma membrane and cytoskeleton (Fig. 1B), whereas AKAP6 was associated with the nuclear membrane (Fig. 1C). As reported previously, AKAP5 is known as a membrane-binding protein (11), and its association with actin was reported in neuronal and epithelial cells (19). The finding that AKAP6 is associated with the nuclear membrane of mouse parotid acini is consistent with the observation made in mouse cardiomyocytes (55). Considering that two other AKAPs, ezrin and myosin-VIIa-and Rab-interacting protein (MyRIP), were shown to be in the apical membrane of mouse parotid acini (2) and apical and granule membranes of rat parotid acini (22), respectively, spatial regulation of the cAMP/PKA pathway via AKAPs is likely to be present in parotid acini.

Previous studies have shown that introducing Ht-31 disrupted the interaction between AKAP and PKA in secretory cells(26, 54). However, since Ht-31 competes with the binding of PKA to AKAPs without specificity, it was not possible to establish the contribution of a specific AKAP in physiological processes using this compound. Therefore, the generation of AKAP5 KO mice was deemed necessary for establishing a role for AKAP5 in regulating amylase secretion from parotid acini. In the present study, we show that isoproterenol-stimulated secretion was reduced by 30–40% overall in acini from AKAP5 KO mice, while stimulation of secretion by forskolin, an activator of ACs (23), and 6-Phe-cAMP, a PKA-specific activator, (44) was not affected. The partial reduction of isoproterenol, but not of 6-Phe-cAMP or forskolin-stimulated amylase secretion in AKAP5 KO mice, revealed that AKAP5-mediated secretion occurs at the receptor level of the cAMP pathway. AKAP5 was shown to interact with β1-adrenergic receptor (18), the major β-adrenergic receptor in mouse parotid acini (9). Its downstream molecule, AC6, an adenylyl cyclase reported to be stimulated by isoproterenol in mouse parotid acini (50), is associated with AKAP5 (Fig. 4). Thus, AKAP5 serves as a bridge between the β-adrenergic receptor and AC6, mediating cAMP generation by AC6 and sequential amylase secretion in response to isoproterenol.

Failure to achieve a 100% decrease in amylase secretion from acini of AKAP5 mutant mice suggested that another/other factors are involved. One factor is the ability of isoproterenol to stimulate secretion via activation of another AC, e.g., AC8, that is expressed in mouse parotid acini (50). A second possibility is that isoproterenol activates PKA-I as well as PKA-II to stimulate amylase secretion (37, 48). PKA-I was known not to associate with AKAP5 (21), and thus, may account, at least in part, for the failure to observe complete inhibition of isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion in cells isolated from AKAP5 KO mice. In mouse parotid acini, only PKA-II is associated with AKAP5. PKA-II interaction with other AKAPs is also likely to play a role in stimulated secretion from mouse parotid acini. This hypothesis is substantiated by RII overlay and immunoblot analyses that identify AKAP6 and other AKAPs in mouse parotid acinar cells (Fig. 1). Our recent study (42) suggests that in mouse parotid acini, an AKAP is involved in Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from ryanodine stores, which is necessary for Ca2+-stimulated secretion. It is likely to be AKAP6, which was shown to associate with Ca2+ mobilization from ryanodine stores (41). Additionally, other AKAPs expressed in parotid acini, ezrin (2) and MyRIP (22), are also likely to contribute to cAMP-stimulated secretion.

Data presented in Fig. 8 support the premise that PKA is not the only cAMP effector to stimulate amylase release in parotid acini. Secretion may also be regulated by PKA-independent pathways, because 1) isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion from mouse parotid acini was only partially reduced, i.e., by 30–40% in acini from AKAP5 KO mice; 2) isoproterenol mimicked the effects of the Epac activator 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP in stimulating Rap1, the only known effector for Epac (13), and 3) no significant difference was noted in 8-pMeOPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP-stimulated amylase secretion from acini of WT and AKAP5 KO mice. Unfortunately, the extent of Epac-dependent, isoproterenol-stimulated amylase secretion was not determined, because an inhibitor of Epac is not available.

Epacs are guanine nucleotide exchange factors that are directly activated by cAMP in a PKA-dependent manner (12). Binding of cAMP to Epac leads to a conformational change exposing the GEF domain, which, in turn, activates downstream targets. Rap1 is the only known effector of Epac (7). There are two forms of Epac, i.e., Epac1 and Epac2, which are encoded by different genes. Epac1 is activated both in vitro and in vivo by direct binding to cAMP (12). Epac1 mRNA is ubiquitously expressed in high levels in several tissues including thyroid, kidney, heart, and skeletal muscle (6). Epac2, which contains an additional amino-terminal cAMP-binding site, has a much lower affinity for cAMP. Epac1 has been suggested to play a role in PKA-independent processes in eukaryocytes which include cell proliferation, apoptosis, and secretion (43). In rat parotid acini, Epac1 is localized to intracellular membranes and plasma membrane (45).

In addition to Epac, other PKA-independent molecules/factors, such as small GTPases Rab3D (10, 33, 52), Rap1, and Rac (52), may be involved in secretion as well. Recent data support a potential link between Rap1 and actin dynamics. This comes from the discovery that Rap1 directly interacts with Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors, Tiam1 and Vav2 (1). The recruitment of Rac1 to the plasma membrane and following actin reorganization are key steps toward amylase secretion from pancreatic acinar cells (5). Thus, Tiam1 and Vav2 may serve as bridge proteins between Rap on secretory granules and the actin cytoskeleton near the apical plasma membrane. Although the localization of Tiam1/Vav2 in parotid cells is not known, studies by Michiels et al. (31) support an association with plasma membrane fractions in fibroblasts and COS cells.

In summary, data suggest that stimulation of the β-adrenergic receptor by isoproterenol in mouse parotid acini involves activation of both PKA-dependent and PKA-independent signaling pathways to regulate mouse parotid acinar secretion.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant DE05249 and by a Bridge grant from the University of Washington.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mike Weisenhaus and Blake Nichols for assistance in breeding and genotyping the AKAP5 KO mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur WT, Quilliam LA, Cooper JA. Rap1 promotes cell spreading by localizing Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J Cell Biol 167: 111–122, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggaley E, McLarnon S, Demeter I, Varga G, Bruce JI. Differential regulation of the apical plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase by protein kinase A in parotid acinar cells. J Biol Chem 282: 37678–37693, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauman AL, Soughayer J, Nguyen BT, Willoughby D, Carnegie GK, Wong W, Hoshi N, Langeberg LK, Cooper DM, Dessauer CW, Scott JD. Dynamic regulation of cAMP synthesis through anchored PKA-adenylyl cyclase V/VI complexes. Mol Cell 23: 925–931, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernfeld P. Enzymes of starch degradation and synthesis. Adv Enzymol Relat Subj Biochem 12: 379–428, 1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi Y, Williams JA. A role for Rho and Rac in secretagogue-induced amylase release by pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C22–C32, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 733–738, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bos JL, de Bruyn K, Enserink J, Kuiperij B, Rangarajan S, Rehmann H, Riedl J, de Rooij J, van Mansfeld F, Zwartkruis F. The role of Rap1 in integrin-mediated cell adhesion. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 83–86, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgoyne RD, Morgan A, O'Sullivan AJ. The control of cytoskeletal actin and exocytosis in intact and permeabilized adrenal chromaffin cells: role of calcium and protein kinase C. Cell Signal 1: 323–334, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsoo B, Danielsson A, Henriksson R. Beta 1- and beta 2-adrenoceptor-mediated secretion of amylase from incubated rat parotid gland. Acta Physiol Scand 120: 429–435, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Edwards JA, Logsdon CD, Ernst SA, Williams JA. Dominant negative Rab3D inhibits amylase release from mouse pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem 277: 18002–18009, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dell'Acqua ML, Faux MC, Thorburn J, Thorburn A, Scott JD. Membrane-targeting sequences on AKAP79 bind phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. EMBO J 17: 2246–2260, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396: 474–477, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Silva NJ, Jacobson KL, Ott SM, Watson EL. β-Adrenergic-induced cytosolic redistribution of Rap1 in rat parotid acini: role in secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1667–C1673, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faruque OM, Le-Nguyen D, Lajoix AD, Vives E, Petit P, Bataille D, Hani el-H. Cell-permeable peptide-based disruption of endogenous PKA-AKAP complexes: a tool for studying the molecular roles of AKAP-mediated PKA subcellular anchoring. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C306–C316, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer TH, Gatling MN, Lacal JC, White GC. rap1B, a cAMP-dependent protein kinase substrate, associates with the platelet cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 265: 19405–19408, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita-Yoshigaki J. Divergence and convergence in regulated exocytosis: the characteristics of cAMP-dependent enzyme secretion of parotid salivary acinar cells. Cell Signal 10: 371–375, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner LA, Tavalin SJ, Goehring AS, Scott JD, Bahouth SW. AKAP79-mediated targeting of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to the beta1-adrenergic receptor promotes recycling and functional resensitization of the receptor. J Biol Chem 281: 33537–33553, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorski JA, Gomez LL, Scott JD, Dell'Acqua ML. Association of an A-kinase-anchoring protein signaling scaffold with cadherin adhesion molecules in neurons and epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3574–3590, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall DD, Davare MA, Shi M, Allen ML, Weisenhaus M, McKnight GS, Hell JW. Critical role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring to the L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 via A-kinase anchor protein 150 in neurons. Biochemistry 46: 1635–1646, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herberg FW, Maleszka A, Eide T, Vossebein L, Tasken K. Analysis of A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) interaction with protein kinase A (PKA) regulatory subunits: PKA isoform specificity in AKAP binding. J Mol Biol 298: 329–339, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai A, Yoshie S, Nashida T, Shimomura H, Fukuda M. The small GTPase Rab27B regulates amylase release from rat parotid acinar cells. J Cell Sci 117: 1945–1953, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insel PA, Ostrom RS. forskolin as a tool for examining adenylyl cyclase expression, regulation, and G protein signaling. Cell Mol Neurobiol 23: 305–314, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurihara K, Nakanishi N, Amano O, Yamamoto M, Iseki S. Specific expression of an A-kinase anchoring protein subtype, AKAP-150, and specific regulatory mechanism for Na(+),K(+)-ATPase via protein kinase A in the parotid gland among the three major salivary glands of the rat. Biochem Pharmacol 66: 239–250, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurosu T, Hernandez AI, Wolk J, Liu J, Schwartz JH. Alpha/beta-tubulin are A kinase anchor proteins for type I PKA in neurons. Brain Res 1251: 53–64, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lester LB, Langeberg LK, Scott JD. Anchoring of protein kinase A facilitates hormone-mediated insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14942–14947, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim CJ, Han J, Yousefi N, Ma Y, Amieux PS, McKnight GS, Taylor SS, Ginsberg MH. Alpha4 integrins are type I cAMP-dependent protein kinase-anchoring proteins. Nat Cell Biol 9: 415–421, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mednieks MI, Jungmann RA, Fischler C, Hand AR. Immunogold localization of the type II regulatory subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Monoclonal antibody characterization and RII distribution in rat parotid cells. J Histochem Cytochem 37: 339–346, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mednieks MI, Jungmann RA, Hand AR. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase regulatory subunits in rat parotid acinar cells. Eur J Cell Biol 44: 308–317, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michel JJ, Townley IK, Dodge-Kafka KL, Zhang F, Kapiloff MS, Scott JD. Spatial restriction of PDK1 activation cascades by anchoring to mAKAPalpha. Mol Cell 20: 661–672, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michiels F, Stam JC, Hordijk PL, van der Kammen RA, Ruuls-Van Stalle L, Feltkamp CA, Collard JG. Regulated membrane localization of Tiam1, mediated by the NH2-terminal pleckstrin homology domain, is required for Rac-dependent membrane ruffling and C-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. J Cell Biol 137: 387–398, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa Y, Purushotham KR, Wang PL, Fischer JE, Dunn WA, Schneyer CA, Humphreys-Beher MG. Alterations in the subcellular distribution of p21ras-GTPase activating protein in proliferating rat acinar cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 187: 1172–1179, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohnishi H, Samuelson LC, Yule DI, Ernst SA, Williams JA. Overexpression of Rab3D enhances regulated amylase secretion from pancreatic acini of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 100: 3044–3052, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okumura K, Tojyo Y, Kanazawa M. Changes in microfilament distribution during amylase exocytosis in rat parotid salivary glands in vitro. Arch Oral Biol 35: 677–679, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozawa T, Nishiyama A. Characterization of ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ release from microsomal vesicles of rat parotid acinar cells: regulation by cyclic ADP-ribose. J Membr Biol 156: 231–239, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perrin D, Moller K, Hanke K, Soling HD. cAMP and Ca(2+)-mediated secretion in parotid acinar cells is associated with reversible changes in the organization of the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol 116: 127–134, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quissell DO, Barzen KA, Deisher LM. Rat submandibular and parotid protein phosphorylation and exocytosis: effect of site-selective cAMP analogs. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 4: 443–448, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raymond DR, Wilson LS, Carter RL, Maurice DH. Numerous distinct PKA-, or EPAC-based, signalling complexes allow selective phosphodiesterase 3 and phosphodiesterase 4 coordination of cell adhesion. Cell Signal 19: 2507–2518, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhim JH, Jang IS, Yeo EJ, Song KY, Park SC. Role of protein kinase C-dependent A-kinase anchoring proteins in lysophosphatidic acid-induced cAMP signaling in human diploid fibroblasts. Aging Cell 5: 451–461, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson HR, Gibson ES, Benke TA, Dell'Acqua ML. Regulation of postsynaptic structure and function by an A-kinase anchoring protein-membrane-associated guanylate kinase scaffolding complex. J Neurosci 29: 7929–7943, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruehr ML, Russell MA, Ferguson DG, Bhat M, Ma J, Damron DS, Scott JD, Bond M. Targeting of protein kinase A by muscle A kinase-anchoring protein (mAKAP) regulates phosphorylation and function of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 278: 24831–24836, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saino T, Watson EL. Inhibition of serine/threonine phosphatase enhances arachidonic acid-induced [Ca2+]i via protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C88–C96, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seino S, Shibasaki T. PKA-dependent and PKA-independent pathways for cAMP-regulated exocytosis. Physiol Rev 85: 1303–1342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah K, Liu Y, Deirmengian C, Shokat KM. Engineering unnatural nucleotide specificity for Rous sarcoma virus tyrosine kinase to uniquely label its direct substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 3565–3570, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimomura H, Imai A, Nashida T. Evidence for the involvement of cAMP-GEF (Epac) pathway in amylase release from the rat parotid gland. Arch Biochem Biophys 431: 124–128, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skalhegg BS, Tasken K. Specificity in the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Differential expression, regulation, and subcellular localization of subunits of PKA. Front Biosci 5: D678–D693, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spearman TN, Butcher FR. Rat parotid gland protein kinase activation. Relationship to enzyme secretion. Mol Pharmacol 21: 121–127, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takuma T. Evidence for the involvement of cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the exocytosis of amylase from parotid acinar cells. J Biochem 108: 99–102, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. 1979. Biotechnology 24: 145–149, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson EL, Jacobson KL, Singh JC, Idzerda R, Ott SM, DiJulio DH, Wong ST, Storm DR. The type 8 adenylyl cyclase is critical for Ca2+ stimulation of cAMP accumulation in mouse parotid acini. J Biol Chem 275: 14691–14699, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson EL, Singh JC, Jacobson KL. Augmentation of cholinergic-mediated amylase release by forskolin in mouse parotid gland. Life Sci 37: 2531–2537, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams JA, Chen X, Sabbatini ME. Small G proteins as key regulators of pancreatic digestive enzyme secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E405–E414, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 959–970, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie G, Raufman JP. Association of protein kinase A with AKAP150 facilitates pepsinogen secretion from gastric chief cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G1051–G1058, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang J, Drazba JA, Ferguson DG, Bond M. A-kinase anchoring protein 100 (AKAP100) is localized in multiple subcellular compartments in the adult rat heart. J Cell Biol 142: 511–522, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]