Abstract

Factors contributing to the development of a fibrotic vascular scar and pulmonary vascular remodeling leading to chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) are still unknown. This study investigates the potential contribution of multipotent progenitor cells and myofibroblasts to the development and progression of CTEPH. Histological examination of endarterectomized tissues from patients with CTEPH identified significant neointimal formation. Morphological heterogeneity was observed in cells isolated from these tissues, including a network-like growth pattern and the formation of colony-forming unit-fibroblast-like colonies (CFU-F). Cells typically coexpressed intermediate filaments vimentin and smooth muscle α-actin. Cells were characterized by immunofluorescence and quantitated by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) for the presence of cell surface markers typical of mesenchymal progenitor cells; cells were >99% CD44+ CD73+, CD90+, CD166+; >80% CD29+; 45–99% CD105+; CD34− and CD45−. Cells were capable of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation, determined by Oil Red O and Alizarin Red staining, respectively. Additionally, a population of Stro-1+ cells, a marker of bone marrow-derived stromal cells (4.2%), was sorted by FACS and also capable of adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation. In conclusion, this study is the first to identify a myofibroblast cell phenotype to be predominant within endarterectomized tissues, contributing extensively to the vascular lesion/clot. This cell may arise from transdifferentiation of adventitial fibroblasts or differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. The unique microenvironment created by the stabilized clot is likely a factor in stimulating such cellular changes. These findings will be critical in establishing future studies in the development of novel and much needed therapeutic approaches for pulmonary hypertension.

Keywords: progenitor cells, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, occlusion, remodeling

chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is a relatively common and very serious complication of acute pulmonary embolism; it is estimated that up to 4% of patients with acute pulmonary embolism develop CTEPH (2, 19). Presently, the clinical and hemodynamic features of the disease are well defined (4, 16, 32). To enable effective therapeutic and diagnostic strategies to be implemented for identification and prevention of CTEPH and to decrease the mortality, it is crucial to understand the associated pathophysiology and cell types contributing to the progression of the disease.

In addition to fibrotic coagulant material occluding the central pulmonary artery, vascular remodeling in arterial segments that are both surrounding (proximal) and distal to the occluded regions contributes to the elevated pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with CTEPH. Proximal and distal pulmonary arterial remodeling is generally associated with 1) excessive proliferation and migration of smooth muscle and endothelial cells (20, 26), 2) proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (27), and 3) accumulation of circulating inflammatory cells (13). It is also hypothesized that vascular progenitor cells, both resident in the vascular wall and circulating progenitor/precursor cells, which may become trapped in the thrombus, may play a role in the formation of fibrotic coagulant thromemboli and the proximal/distal vascular wall thickening (5). Misguided differentiation of these progenitor cells toward a smooth muscle cell (SMC)/fibroblast-like phenotype may enhance the vascular dysfunction. SMCs can be identified by a set of protein markers restricted to the smooth muscle lineage. Smooth muscle α-actin identifies SMC at early stages of differentiation. As SMC mature to a contractile phenotype established expression of other markers, such as smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) and smoothelin, are upregulated (28). More primitive myofibroblasts typically express type III filament vimentin (30). Furthermore, circulating mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells are associated with the expression of cell surface markers CD29, CD73, CD90, and CD105 (1, 6) and cells of stromal origin with expression of Stro-1 (14). Interestingly, mechanical stress, such as that which may be endured by pulmonary arteries during hypertension or in the presence of the fibrotic embolism, has been shown to promote the expression of smooth muscle-like properties in marrow stromal cells (14).

Factors associated with the unresolved clot may serve to trigger or potentiate this erroneous cell proliferation. Mitogenic, inflammatory, and vasoactive factors may become trapped in the prevailing fibrotic thrombus. Unique access to endarterectomized tissues from CTEPH patients enabled this novel study to investigate the phenotype of cells isolated from surgically removed pulmonary vascular tissues from patients undergoing pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Preparation and culture of cells from PTE tissues.

Surgically removed pulmonary vascular tissues from patients with CTEPH undergoing PTE were used in this study. Written informed consent was acquired before surgery from all 10 patients from whom tissue samples were obtained. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego (La Jolla, CA). PTE tissue, removed from patients in the operating room, was immediately placed in cold (4°C) PBS and microdissected in the laboratory. Tissues were incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2.5 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical), 0.5 mg/ml elastase (Sigma), and 1.0 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) for 55 min at 37°C to create a cell suspension. After the incubation, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added and cells were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 5 min. The single cells were resuspended, plated onto 25-mm coverslips or T-25 flasks, and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C in smooth muscle growth medium (SMGM, Cambrex) composed of smooth muscle basal medium (SMBM, Cambrex), 10% FBS, human epidermal growth factor, human fibroblast growth factor-B, and insulin for 1 wk. The medium was changed every 2 days. After reaching confluence, the cells were passaged using TrypLE (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and used for experiments as primary cells and at passages 2–6. Human pulmonary adventitial fibroblasts (hPAF; ScienCell) and human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMC; Lonza) were used where necessary as control cells.

Preparation and culture of rat PASMC.

Primary cultured pulmonary artery SMCs (PASMC) were prepared from the pulmonary arteries of male Sprague-Dawley rats (125–250 g). Briefly, isolated pulmonary arterial rings were incubated for 20 min in HBSS containing 1.5 mg/ml of collagenase (Worthington). Subsequently, the adventitia was carefully stripped off by a fine forcep and the endothelium removed by gentle perturbation of the intimal surface with a surgical blade. With the use of 2.0 mg/ml collagenase and 0.5 mg/ml elastase (Sigma), the remaining smooth muscle was digested for 45 min at 37°C. The cells were plated onto 25-mm coverslips for immunofluorescence studies in 10% FBS-DMEM and cultured in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator.

Histochemistry.

Pieces of tissue were isolated from regions surrounding the occlusion (referred to as proximal) and from regions distal to the occlusion (referred to as distal). These were embedded and frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Sakura Tissue Tek). Frozen sections (10-μm) were cut on a cryostat. Standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and counterstaining with elastin van Gieson (EVG) were performed on the slides as per the manufacturer's instructions. For subsequent studies, the sections were stained using the SMαA antibody and the ABC Staining System (Santa Cruz Biotech) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Morphological analysis.

Morphology of the cells was analyzed by phase-contrast images taken on an inverted Nikon Eclipse/TE200 coupled to a Sony-SSC-D5 monochrome video camera, using a charge-coupled device. Images were taken by using both ×10 and ×20 objective lenses, as indicated in the text.

Immunofluorescence.

The cells, cultured on 25-mm coverslips, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were then incubated with primary antibodies in blocking solution (PBS supplemented with 4% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2% normal serum; Santa Cruz Biotech) overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorescent probes. Cells were counterstained with nuclear dye, DAPI (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotech) and mounted in anti-fade Fluoromount-G mounting medium (Southern Biotech) for imaging on either an Olympus DSU disc spinning microscope and SlideBook software or a Delta Vision deconvolution microscope system (Nikon TE-200) and softWoRx Suite (Applied Precision). The images were processed by Image J (NIH software) and Photoshop (Adobe) software packages.

Fluorescent-activated cell sorting.

CTEPH cells and normal pulmonary adventitial fibroblasts (ScienCell) were analyzed by fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS). Briefly, cells were dissociated using TrypLE, centrifuged at 4°C, washed in cold PBS, and centrifuged again. Cells were resuspended in buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 0.1% NaN3) to aliquot into a total of 100 μl with directly conjugated antibodies and incubated on ice in the dark for 30 min. Cells were centrifuged, washed, and centrifuged before resuspension in cold buffer (200–500 μl dependent on cell number) and then transferred to FACS tubes. For analysis only cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde/PBS and analyzed on a BD Biosciences FACSCanto. A DakoCytomation MoFlo was used to sort cells (Stro-1+) that were collected in media (DMEM low glucose with Glutamax, Invitrogen) with 20% FBS and plated on collagen-coated dishes in media with 10% FBS. Only antibodies directly conjugated with fluorescent probes were used for FACS analysis.

RT-PCR.

To determine the mRNA expression of markers typically expressed in different cell types, RT-PCR was performed. Total RNA [ratio of optical density (OD) at 260 nm to OD at 280 nm > 1.6] was prepared from CTEPH cells, human PASMCs, and human adventitial fibroblasts using TRIzol (Invitrogen). All RNA was DNase treated and reverse transcribed with the Superscript first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Negative controls omitting the reverse transcriptase were prepared and checked concomitantly by RT-PCR for genomic contamination (data not shown). The sense and antisense intron spanning primers were specifically designed from the coding regions of the markers and checked for fidelity and specificity using the BLAST program. The primers are listed in Table 1. The cDNA samples were amplified in a DNA thermal cycler (MyCycler, Bio-Rad), the PCR products were electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose gel, and amplified cDNA bands were visualized by GelStar nucleic acid stain (Lonza). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide sequences of the primers user for RT-PCR

| Standard Names (Reference No.) | Size, bp | Predicted Sense/Antisense | Location, nt | Gene (Chromosome) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMαA | 308 | GCATCCATGAAACCACCTAC | 871–1197 | 10q22-q24 |

| (NM_001613.1) | GAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACAA | |||

| Smoothelin | 516 | GACTTTGAAGAGCGGAAGCT | 2019–2535 | 22q12 |

| (NM_134269.1) | CTCCAGCTTCTCAATCATGG | |||

| SM-MHC | 180 | GGTTGGCGACTGTTCTTTCC | 2509–2688 | 2p16.3 |

| (NM_152994.2) | CTTCTGTATTTGCCTCACTGGTTA | |||

| SM-22α | 372 | ACCTCGGCAGATCATCAGTTAG | 1103–1474 | 11q23.2 |

| (NM_001001522) | GGTTCTTCTTCAATGGGCTTTT | |||

| Vimentin | 390 | GTGGATGTTTCCAAGCCTGA | 896–1285 | 10p13 |

| (NM_003380.2) | GAGCAGGTCTTGGTATTCAC | |||

| CD-117 (c-kit) | 342 | CGTTTGAAAGTGACGTCTGG | 2561–2902 | 4q11-q12 |

| (NM_000222) | CGACAGAATTGATCCGCACA | |||

| Nestin | 366 | CATTGGTGTTAATGGCCAGG | 4729–5094 | 1q23 |

| (NM_006617.1) | GTTAAGAGTGCTGCTCCTGA | |||

| Desmin | 301 | GTACAAGTCGAAGGTGTCAG | 971–1274 | 2q35 |

| (NM_001927.3) | CATCTTCACGTTGAGCAGGT | |||

| CD29 | 385 | CTGCAGTAACAATGGAGAGTGC | 1708–2092 | 10p11.2 |

| (NM_133376.1) | GAAGGCTCTGCACTGAACACAT | |||

| CD73 | 386 | CACAGGCAATCCACCTTCCAAA | 796–1181 | 6q14-q21 |

| (NM_002526.1) | CATCCGTGTGTCTCAGGTTGTT | |||

| CD90 | 428 | CTCCCTGCCTAAGGAAGCTAAA | 1279–1706 | 11q22.3-q23 |

| (NM_006288.3) | GTGGCACTATACACAGTCACAG | |||

| GAPDH | 243 | GACAACGAATTTGGCTACAGC | 1045–1287 | 12p13.31 |

| (NM_002046.3) | GATGGTACATGACAAGGTGC |

Differentiation experiment.

For osteogenic differentiation, cells were plated on 16-well CultureWell slides (Invitrogen). Regular medium was replaced by osteogenic differentiation medium (Invitrogen) for 7–24 days. At day 7, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 min and stained with alkaline phosphatase (15 min) (Chemicon International) and after 14–21 days, cells were fixed for 10–15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Alizarin Red (10 min) (Sigma). For adipogenic differentiation cells were plated on 16-well CultureWell slides. Medium was replaced with adipogenic differentiation medium (Invitrogen), and after 7–21 days, cells were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Oil Red O lipid stain for 10 min (Sigma). For each condition, 12 differentiation and 4 control experiments were conducted for each of three patient PTE-derived cell populations.

Reagents.

Antibodies used in the study were smooth muscle α-actin (1:400, Sigma); CD105, CD73-PE (BD Biosciences); CD73, Stro-1, Stro-1-FITC, CD34 (Santa Cruz Biotech), Vimentin, CD166-PE (R&D Systems,); and CD29-PE-Cy5, CD44-AlexaFluor 700, CD45 PerCP-Cy5.5 (eBioscience). Secondary antibodies conjugated to FITC (1:200, Sigma) and Rhodamine Red (1:200, Jackson Laboratories) were used. Unless otherwise stated, antibodies were used at 1:50 for immunofluorescence and directly conjugated antibodies at 1:5 for FACS.

RESULTS

Endarterectomized tissues from CTEPH patients, who were graded with class II and III functional severity of disease based on the New York Heart Association Classification, were obtained for the study. Preoperative mean pulmonary arterial pressure ranged from 49 to 56 mmHg with the pulmonary vascular resistance ranging from 502 to 1,150 dyn·s−1·cm5.

Pulmonary artery vascular remodeling in CTEPH.

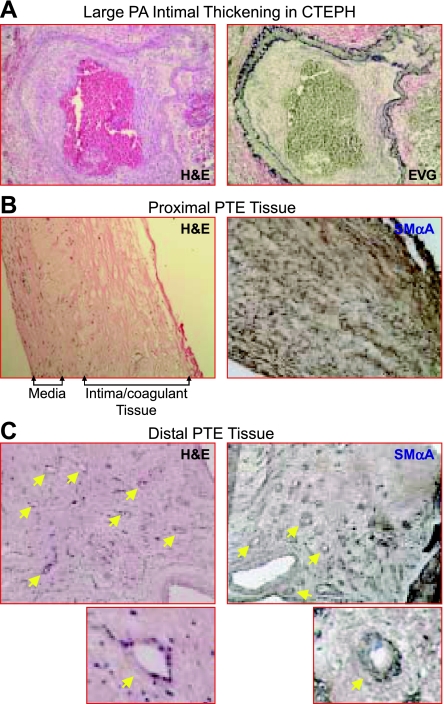

Lung autopsy specimens from CTEPH patients were analyzed for structural abnormalities in the large pulmonary artery. Histological analysis indicated significant intimal thickening and neointimal formation in the large pulmonary artery. In Figure 1A, representative histology sections from autopsy lung samples from patients with CTEPH are stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Fig. 1, left) and counter stained with elastin van Gieson (right). In these images distinct elastic lamiae are evident with gross neointimal thickening surrounding the occluded artery (right). Cells can be seen within this region and throughout the occluding fibrotic clot region.

Fig. 1.

Histological analysis of autopsy and endarterectomized tissues (PTE) from chronic chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patients. A: autopsied lung sections from CTEPH patients stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, left) and costained with elastin van gieson (right). Sections from endarterectomized tissues in the region of the fibrotic clot (proximal, B) and in the regions distal to the fibrotic clot (distal, C), H&E staining (left; ×60) are shown. Smooth muscle α-actin (SMαA) staining is shown (brown in right). In the proximal region (B), the smooth muscle layer in the media and fibrotic coagulant tissue mixed with the intimal layer are indicated. In the distal region (C), the recanalization small vessels are indicated by yellow arrows.

During PTE, to ensure maximal resolution of the obstructed artery, both the fibrotic clot region and the innermost layers of the pulmonary artery are excised. This includes the neointimal layer and 1–2 layers of SMC from the media, taken from both the region in close proximity to the obstruction and also in vessels 1–2 divisions distal to the occlusion. Although not clinically accurate, for the purpose of defining the regions in this study, cells and tissue sections taken from the region directly surrounding the fibrotic clot are referred to as “proximal” vascular tissue and those taken from areas after the fibrotic clot region are referred to as the “distal” vascular tissue (29). Immunostaining of the tissue sections indicated a significant amount of general SMαA staining with a distinct smooth muscle layer representing the media of the large pulmonary artery. Histological analysis of sections indicates a fibrin/collagen network embedded with a distinct medial layer and neointimal formation (Fig. 1B, left). SMαA-expressing cells are present throughout this proximal PTE region (Fig. 1B, right). In the more distal PTE sections, a substantial recannalization of the thickened arterial wall is evident. Recannalized regions are indicated by the arrows in the H&E- and SMαA-stained tissue sections (Fig. 1C). Additionally, formation of smooth muscle layers surrounding the newly formed vessels can be seen.

Morphological heterogeneity in PTE tissue-derived cells.

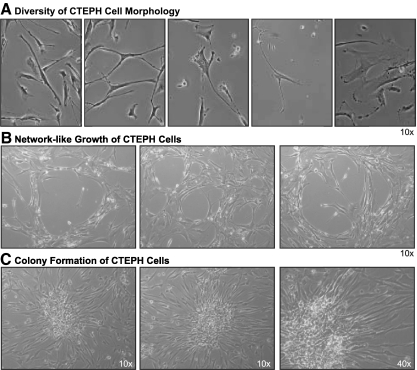

Cells were isolated from the PTE tissues and maintained in culture. Phase-contrast imaging of primary cultured cells highlights a substantial diversity in morphology of the cells, diverging from the typically elongated spindle shape morphology of smooth muscle cells. Regularly observed phenotypes in endarterectomized tissue-derived cells from CTEPH patients included: 1) typical elongated smooth muscle cells, 2) shortened more primitive precursor type cells, 3) myofibroblasts encompassing a retractile cell body with an array of processes having several orders of bifurcation, 4) cells with small cell bodies and multiple long processes, and 5) large, flatter cells. Representative images of varied cell types, observed in all PTE tissue-derived patient cells, are shown in Fig. 2A. The cells regularly formed a honeycomb type network in culture, indicative of adventitial fibroblasts (Fig. 2B). Most interestingly, cells from all CTEPH patients consistently formed colonies in culture. Representative colony units are shown in Fig. 2C. The colonies composed of small round cells clustered in the center surrounded by more elongated cells fanning radically from the cluster. These cells resemble colony-forming unit fibroblasts (CFU-Fibroblasts) (10).

Fig. 2.

Morphological diversity exists in cells isolated from the PTE tissues. A: representative phase-contrast images of morphologically distinct cells isolated from PTE tissues (×20). B: honeycomb “network-like” growth of isolated cells (×10). C: representative phase-contrast images of colony formation by isolated cells (×10, left; and ×40, right).

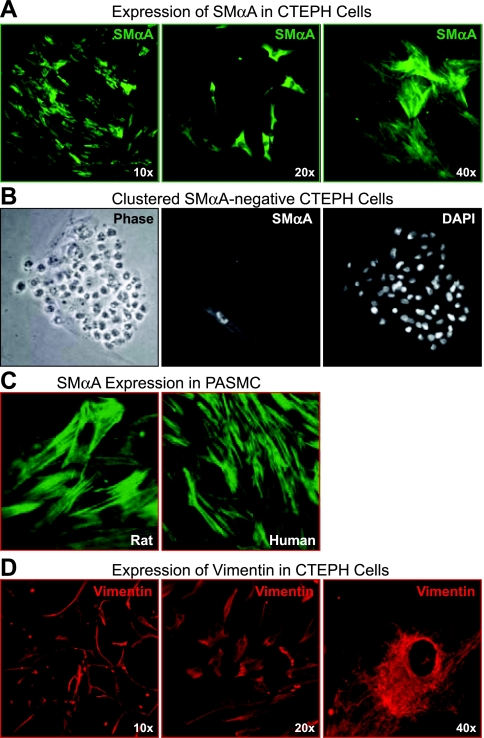

A myofibroblast-like cell phenotype is predominant in PTE tissue.

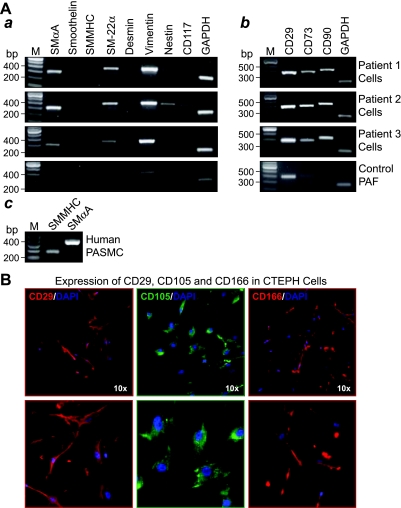

To determine the cell types constituting the PTE tissue; RT-PCR, immunofluorescence and FACS techniques were utilized to study the presence of markers typical of mature smooth muscle cells, in addition to other, more primitive, mesenchymal cell types. Markers included 1) SMαA as a marker of SMC, present in both immature and fully mature SMC; 2) transgelin (SM-22α), a calponin that is one of the earliest markers of smooth muscle differentiation; 3) smoothelin, a cytoskeletal filament expressed in fully mature contractile smooth muscle cells; 4) SM-MHC, a contractile protein found in mature SMC; 5) desmin, a type III intermediate filament found near the Z line in sarcomeres and one of the early markers for muscle during embryogenesis; 6) nestin, a type VI intermediate filament protein transiently expressed in many cell types during development and is predominantly in neural precursor cells; and 7) vimentin, an intermediate filament marker typically characteristic of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Vimentin is a cytoskeletal component responsible for maintaining cell integrity and is dynamic in nature in fibroblast cells. In addition, expression of CD117 (c-kit receptor), a cytokine receptor expressed on several cell types though typically associated with hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors cells, was assessed. Functional signaling via CD117 contributes to cellular processes such as cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation (23).

As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, cells isolated from the PTE tissue display differential staining by SMαA. Although SMαA-positive cells accounted for >85% of the total cells, there was much diversity within these positive cells as to the extent and pattern of this staining. Some cells had well-defined actin filament structures representative of a more mature SMC with an established contractile phenotype (Fig. 3A, left and right); some cells contained strong staining within the cytoplasm but with no defined actin filaments, suggesting a more immature SMC type, perhaps myofibroblasts (Fig. 3A, middle); others had very weak or no staining. Figure 3B shows a cluster of stem cell-like cells (left). Whereas the stem cell-like cells stained heavily with DAPI, indicating dense clustering nuclei (right), they did not stain at all with SMαA (middle), suggesting the presence of primitive cells with no SMC characteristics. Only a more regular elongated cell on the edge of this cluster stained for SMαA (Fig. 3B, middle). In rat PASMC, isolated with a similar methodology, SMαA staining gives a uniform filamentous staining in all the cells, indicative of a population of mature SMC with defined actin filaments (Fig. 3C). Vimentin was strongly expressed in all cells with defined filamentous staining (shown in the representative images at varied magnifications in Fig. 3D) and a strong mRNA signal (Fig. 4Aa).

Fig. 3.

Myofibroblasts are identified in cells isolated from PTE tissues. A: representative immunofluorescent images showing both general cytoplasmic or defined actin filament staining with SMαA (green). B: phase and immunofluorescent images of a cluster of SMαA-negative cells, nuclei are counterstained with DAPI. C: defined SMαA filament staining (green) in freshly isolated smooth muscle cells from rat pulmonary artery and human pulmonary artery. D: intermediate filament, vimentin (red), staining is shown at increasing magnification in representative images.

Fig. 4.

Markers for myofibroblasts and mesenchymal progenitors are expressed in cells isolated from PTE tissues. A: representative RT-PCR gel images showing mRNA expression for cell surface markers and cytoskeletal filaments associated with immature and progenitor cell types in isolated PTE cells. B: positive RT-PCR control showing mature smooth muscle marker, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC). C: representative immunofluorescent images showing expression of cell surface markers CD29, CD105, and CD166 typical of mesenchymal stem cells; bottom images are enlarged sections of the ×10 magnification top panels. PAF; pulmonary adventitial fibroblast.

RT-PCR was carried out on RNA extracted from the total isolated cell population for each patient. Intron spanning primers were designed specifically for sequences of these aforementioned cell type markers (Table 1). The RT-PCR results confirmed the presence of the early smooth muscle differentiation markers SMαA and transgelin, whereas the markers of more mature contractile smooth muscle were not detected. In addition, intermediate filaments' nestin and vimentin were detected in all patient cells and CD117 was frequently detected. The presence of these intermediate filaments and the cytokine receptor is suggestive of the presence of more primitive precursor type cells and not fully mature cells. Furthermore, the patient cells all strongly expressed cell surface markers CD29, CD73, and CD90, typical of mesenchymal lineage, and, more specifically, mesenchymal stem or progenitor cells (Fig. 4Ab). Immunofluorescent staining confirmed the expression of CD73 and CD29 at the protein level and additionally demonstrated strong immunostaining of CD105 and CD166 as shown in the representative images of the patient cells in Fig. 4B. The bottom panels are enlarged sections of the top panels to highlight the cellular expression of these markers; the nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue).

Mesenchymal progenitor cells.

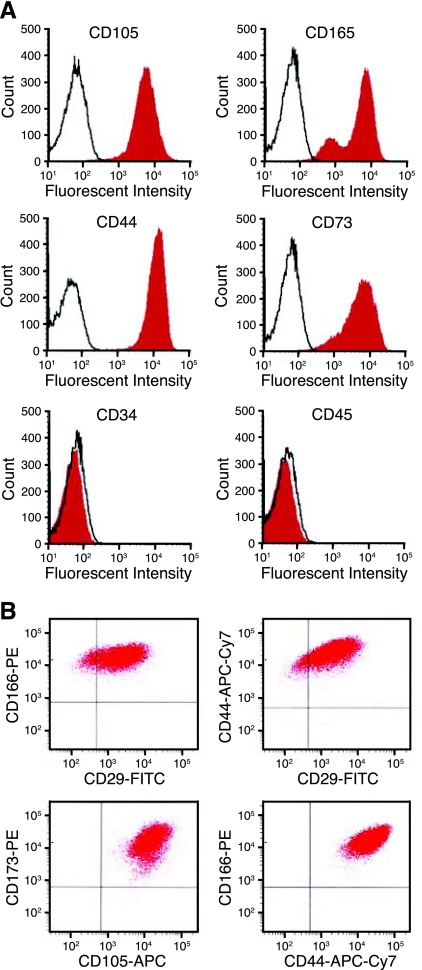

Acquisition of a smooth muscle-like cellular phenotype by circulating progenitor cells and by resident vascular progenitor cells, which have been recruited to sites of vascular injury has been previously shown (9, 12, 15, 22, 25). Given the seemingly primitive nature of the cells present in the PTE cell populations from CTEPH patients, we investigated the potential presence of mesenchymal stem or progenitor cells. Although mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) have a diverse array of phenotypical markers, a core set of the human MSC markers most consistently present were used in this study. Quantitative cell analysis was carried out by FACS using a core set of five positive and two negative cell surface markers; positive, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD105, CD166 and negative for CD34 and CD45. The patient cell populations were greater than 95% positive for CD44, CD73, and CD166 and negative for CD34 and CD45 (<0.2% of the parent population). Cells expressing CD29 and CD105 correlated to 69.2 ± 5.8% and 70.8 ± 14.9% of the parent population (n = 3). Representative FACS histograms and double-stained scatter plots for cells isolated from PTE tissues from a CTEPH patient are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

CD105, CD166, CD44, CD73 positive, CD34 and CD45 negative cells are present in cells isolated from PTE tissues. A: representative histograms of fluorescent activated cells sorting for cell surface markers present or absent in mesenchymal stem cells. B: dot plots of double-stained CTEPH cells.

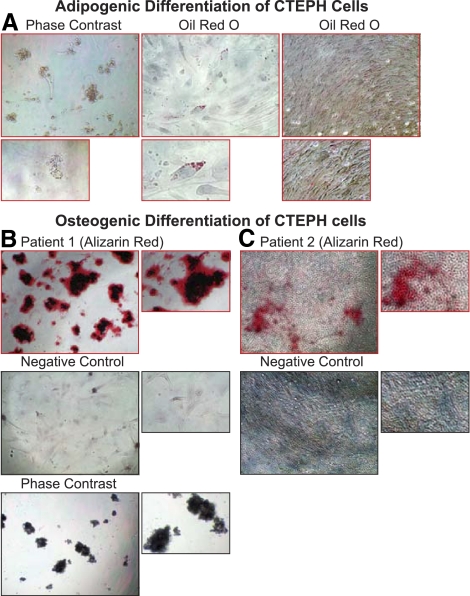

Differentiation capacity of the PTE tissue-derived cells.

Currently the minimal criteria of a mesenchymal stem cell, as determined by the International Society for Cellular Therapy, are that the cells are plastic adherent, express CD73, CD90, CD105, and are capable of undergoing differentiation into multiple lineages, including adipogenesis, osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, and myogenesis (8). The differentiation capacity of the PTE cells from CTEPH patients was assessed by using defined differentiation media and protocols (Invitrogen). Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation capacities were assessed after 7 and 24 days. After 7 days, adipogenic differentiation, determined by Oil Red O lipid staining, was present in all patient cells (Fig. 6A). Osteogenic differentiation of the cells was determined at 7 days by alkaline phosphatase staining and 24 days by alizarin Red staining for calcium-rich deposits. Cells readily differentiated toward osteogenic lineage and, after 24 days, formed distinct clusters strongly staining for alizarin red. The representative images (Fig. 6, B and C) show the negative controls in the bottom panels for experiments maintained in standard media and the differentiation in the top panels indicating alizarin red staining at 24 days differentiation.

Fig. 6.

PTE tissue-derived cell populations are capable of adipogenesis and osteogenesis. A: adipogenic differentiation (7 days); left, representative phase contrast image (×10). Center and right, subconfluent and confluent cells stained with Oil Red O lipid stain. Bottom, enlarged sections of the top panels for clarity. B and C: osteogenic differentiation (24 days) in two PTE tissue-derived cell populations from different patients. Top panels show cells in differentiation conditions stained with Alizarin Red; center panels show Alizarin Red staining of cells maintained in standard media (negative control); and bottom panel in B shows a representative phase contrast image (×10).

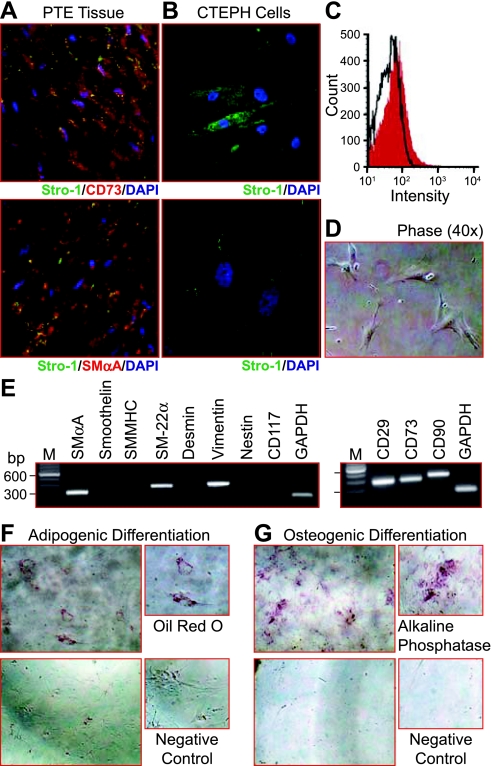

A subpopulation of multipotent Stro-1+ cells in PTE tissue-derived cells.

In light of the consistent formation of colony forming units, the expression of Stro-1 was assessed in the PTE cells. Stro-1 identifies clonogenic bone marrow-derived stromal cell progenitors, which form fibroblast colony-forming units (CFU-F). These cells are known to generate cells with a fibroblast-like phenotype, adipocytes, smooth muscle-like cells and can undergo osteogenesis (7). Given the potential for differentiation of cells maintained in culture, the presence of Stro-1 was initially assessed in tissue sections from the PTE tissues. Stro-1 expression was detected in the tissue sections, also with expression of CD73 and SMαA as indicated in the immunofluorescent images (Fig. 7A). Stro-1 expression was also detected in isolated cells (Fig. 7B). A small population (4.2%) of Stro-1 expressing cells was sorted by FACS (Fig. 7C). The sorted cells were expanded on collagen IV-coated plates and were more uniform in morphology. The phase-contrast image in Fig. 7D shows sorted cells 2 days after plating. After 7 days these single cells formed colonies from which either RNA was extracted or cells were split for assessment of the differentiation potential. RT-PCR determined expression of SMαA, transgelin (SM-22α), and vimentin in addition to CD29, CD73, and CD90 (Fig. 7E). At day 7 of differentiation some adipogenesis was observed; however, a more distinct expression of alkaline phosphatase indicates that the cells readily differentiate toward an osteogenic lineage (Fig. 7, F and G, respectively).

Fig. 7.

A subpopulation of multipotent Stro-1+ cells is present in CTEPH cells. A: Stro-1+ cells (green) are detected in PTE tissue sections and colocalized with CD73 (red, top) and SMαA (red, bottom). B: representative immunofluorescent images of Stro-1+-isolated cells (green). C: histogram summarizing the fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis for Stro-1 in cells isolated from PTE tissues, a 4.2% positive population was sorted. D: phase contrast (×40) image showing morphological homogeneity of Stro-1+ isolated cells. E: representative RT-PCR gel images showing mRNA expression for cell surface markers and cytoskeletal filaments associated with immature and progenitor cell types in Stro-1+ cells. F and G: representative brightfield images indicating adipogenic (Oil Red O, F) and osteogenic alkaline phosphatase, G: differentiation of Stro-1+, respectively. Images are takes at 7 days of differentiation at ×10; top panels are cells in differentiation media and bottom panels are cells in standard culture conditions.

DISCUSSION

The results of the study describe a diverse morphological phenotype of cells present in the endarterectomized tissues from CTEPH patients. This study identifies a substantial presence of progenitor cell types of a mesenchymal-derived lineage in the arterial segments in close proximity to the thromboembolic tissue in CTEPH patients. The formation of fibrotic clot tissues in the central pulmonary artery and the thickening of vascular wall are potentially driven by dysregulated differentiation and proliferation progenitor cells into a myofibroblast cell phenotype. In addition, migration of resident adventitial fibroblasts and a phenotypic change to myofibroblasts [shown to occur in the presence of thrombin (3)] in the smooth muscle medial layers may contribute significantly to the pulmonary vascular remodeling observed in CTEPH.

Phase-contrast microscopy identified a diverse morphological phenotype of the cells isolated from the endarterectomized tissues. Such diversity was not observed in cells isolated using similar methodology from the pulmonary arteries of rats, suggesting a genuine cellular heterogeneity in PTE cells from CTEPH patients. Whereas the presence of vimentin is most commonly associated with fibroblasts, the coexpression of SMαA in most of the cells isolated from the endarterectomized tissues suggests that these cells are unlikely pure fibroblasts and that the cells have mostly differentiated along a SMC-type lineage to at least the level of myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts are SMαA-expressing fibroblasts that have been shown to be characteristic in the vascular remodeling observed in animals with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (9, 11). Myofibroblasts were originally thought to originate from differentiation of resident fibroblasts in the adventitia (21); however, a recent paper by Frid et al. (9) also showed evidence for mononuclear cells of a monocyte/macrophage lineage to form myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts have not yet been observed to fully differentiate into SMCs and generally form a population of mesenchymal progenitor cells that are distinct from circulating smooth muscle precursor cells(24). Once active, they are known to release proinflammatory cytokines, promitogenic and proangiogenic factors that can subsequently contribute to vasoconstriction, cell proliferation, and increased vascular permeability, having potent effects on the resident SMCs in the vasculature tissue as well (11, 18). In addition, they have been shown to secrete extracellular matrix protein collagen; indeed studies have demonstrated a myofibroblast cell phenotype to be responsible for increased lung collagen gene expression during pulmonary fibrosis (31). Our studies also indicate a significant collagen deposition in the fibrin matrix of the fibrotic clot in CTEPH patients (29).

Typically, selective isolation and growth of cells isolated from pulmonary arteries produce a fairly uniform population of mature SMCs. The vast diversity of cell types present in the cell population isolated from endarterectomized tissues is indicative of a misguided regulation of SMC turnover in these tissues. Although other studies have shown a contribution of vascular progenitor cells, both circulating and resident in the vascular wall, to arteriosclerosis, such diversity in a population of isolated cells is not observed. Given that the endarterectomized tissue at most contains the tunica intima and the innermost layers of the tunica media, it is unlikely that the cells isolated are direct “contamination” of fibroblasts or macrophages from the tunica adventitia. It is possible that differentiation and migration of more primitive cell types such as myofibroblasts in addition to progenitor cells, is stimulated by factors that accumulate in the unresolved fibrotic clot resulting in vascular cell proliferation and vascular remodeling in the arteries distal to the occlusion. The extent of this remodeling may determine the likelihood of the patient having persistent pulmonary hypertension after surgery. It is also possible that particular factors associated with an unresolved clot and the development of CTEPH may be the stimulus for triggering such cellular dysregulation. For example, reported differences in the resistance to lysis of fibrin isolated from CTEPH patients may form such a stimulus (17).

A fundamental finding of this study is the ability of a large percentage of the CTEPH cells to undergo multilineage differentiation, including adipogenesis, osteogenesis, and myogenesis; suggestive of a cell population composing of progenitor cells. Furthermore, the population of isolated Stro-1 positive cells that also had a similar differentiation capacity indicates a contribution of bone marrow-derived circulating progenitor/stem cells. The correlation between preoperative treatments and genetic predispositions to thromboemboli may form an interesting subsequent study. It will now be essential to obtain tissue samples from more CTEPH patients undergoing PTE surgery and to perform single cell clonogenic assays from the fresh tissues to precisely determine and quantitate the cellular phenotypes. Furthermore, the influence of factors associated with the fibrotic clot such as fibrin and thrombin, on the differentiation and migratory capacity of the respective cells types may shed light on potential mechanisms for recruitment of such cell types to create the intimal lesion in CTEPH patients.

We believe this study is the first to assess the cellular phenotypes and identify myofibroblasts and multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells as the predominant cells comprising the excised PTE tissues from patients with CTEPH. These findings will be critical in establishing future studies to determine the cellular and molecular mechanisms of the disease and in the development of novel and much needed therapeutic approaches.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-066012 and HL-05403) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC-30810103904 and NSFC-2009CB522107). A. L. Firth is supported by a Postdoctoral Training Fellowship from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate the technical support from Jenifer Meerloo in the UCSD Neuroscience Microscopy Shared Facility (NINDS P30 NS047101); Judy Norberg, Peggy O'Keefe, and Neal Sekiya in the Flow Cytometry Research Core Facility of the San Diego Center for AIDS Research (AI 36214) and the Veteran Affairs Research Center for AIDS & HIV Infection (VA San Diego Healthcare System). We also thank the team of surgeons and physicians at the University of California, San Diego Medical Center, who contributed to collecting the tissue specimens from which the cells in this study were derived.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartmann C, Rohde E, Schallmoser K, Purstner P, Lanzer G, Linkesch W, Strunk D. Two steps to functional mesenchymal stromal cells for clinical application. Transfusion 47: 1426–1435, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becattini C, Agnelli G, Pesavento R, Silingardi M, Poggio R, Taliani MR, Ageno W. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Chest 130: 172–175, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogatkevich GS, Tourkina E, Silver RM, Ludwicka-Bradley A. Thrombin differentiates normal lung fibroblasts to a myofibroblast phenotype via the proteolytically activated receptor-1 and a protein kinase C-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 45184–45192, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonderman D, Skoro-Sajer N, Jakowitsch J, Adlbrecht C, Dunkler D, Taghavi S, Klepetko W, Kneussl M, Lang IM. Predictors of outcome in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 115: 2153–2158, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davie NJ, Crossno JT, Jr, Frid MG, Hofmeister SE, Reeves JT, Hyde DM, Carpenter TC, Brunetti JA, McNiece IK, Stenmark KR. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary artery adventitial remodeling and neovascularization: contribution of progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286: L668–L678, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delorme B, Charbord P. Culture and characterization of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Methods Mol Med 140: 67–81, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennis JE, Carbillet JP, Caplan AI, Charbord P. The STRO-1+ marrow cell population is multipotential. Cells Tissues Organs 170: 73–82, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop D, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8: 315–317, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frid MG, Brunetti JA, Burke DL, Carpenter TC, Davie NJ, Reeves JT, Roedersheimer MT, van Rooijen N, Stenmark KR. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling requires recruitment of circulating mesenchymal precursors of a monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am J Pathol 168: 659–669, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedenstein AJ, Latzinik NV, Gorskaya Yu F, Luria EA, Moskvina IL. Bone marrow stromal colony formation requires stimulation by haemopoietic cells. Bone Miner 18: 199–213, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartlapp I, Abe R, Saeed RW, Peng T, Voelter W, Bucala R, Metz CN. Fibrocytes induce an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis in vivo. FASEB J 15: 2215–2224, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu Y, Zhang Z, Torsney E, Afzal AR, Davison F, Metzler B, Xu Q. Abundant progenitor cells in the adventitia contribute to atherosclerosis of vein grafts in ApoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 113: 1258–1265, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura H, Okada O, Tanabe N, Tanaka Y, Terai M, Takiguchi Y, Masuda M, Nakajima N, Hiroshima K, Inadera H, Matsushima K, Kuriyama T. Plasma monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and pulmonary vascular resistance in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 319–324, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi N, Yasu T, Ueba H, Sata M, Hashimoto S, Kuroki M, Saito M, Kawakami M. Mechanical stress promotes the expression of smooth muscle-like properties in marrow stromal cells. Exp Hematol 32: 1238–1245, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C, Nath KA, Katusic ZS, Caplice NM. Smooth muscle progenitor cells in vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14: 288–293, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmud E, Raisinghani A, Hassankhani A, Sadeghi HM, Strachan GM, Auger W, DeMaria AN, Blanchard DG. Correlation of left ventricular diastolic filling characteristics with right ventricular overload and pulmonary artery pressure in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 318–324, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris TA, Marsh JJ, Chiles PG, Auger WR, Fedullo PF, Woods VL., Jr Fibrinogen from patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension is resistant to lysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 1270–1275, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murdoch C, Giannoudis A, Lewis CE. Mechanisms regulating the recruitment of macrophages into hypoxic areas of tumors and other ischemic tissues. Blood 104: 2224–2234, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pengo V, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, Marchiori A, Davidson BL, Tiozzo F, Albanese P, Biasiolo A, Pegoraro C, Iliceto S, Prandoni P, Group TPHS. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 350: 2257–2264, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platoshyn O, Golovina VA, Bailey CL, Limsuwan A, Krick S, Juhaszova M, Seiden JE, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Sustained membrane depolarization and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1540–C1549, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sartore S, Chiavegato A, Faggin E, Franch R, Puato M, Ausoni S, Pauletto P. Contribution of adventitial fibroblasts to neointima formation and vascular remodeling: from innocent bystander to active participant. Circ Res 89: 1111–1121, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sata M. Role of circulating vascular progenitors in angiogenesis, vascular healing, and pulmonary hypertension: lessons from animal models. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 1008–1014, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma S, Gurudutta GU, Satija NK, Pati S, Afrin F, Gupta P, Verma YK, Singh VK, Tripathi RP. Stem cell c-KIT and HOXB4 genes: critical roles and mechanisms in self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation. Stem Cells Dev 15: 755–778, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simper D, Stalboerger PG, Panetta CJ, Wang S, Caplice NM. Smooth muscle progenitor cells in human blood. Circulation 106: 1199–1204, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenmark KR, Davie N, Frid M, Gerasimovskaya E, Das M. Role of the adventitia in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 134–145, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stenmark KR, Fagan KA, Frid MG. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ Res 99: 675–691, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenmark KR, Gerasimovskaya EV, Nemenoff RA, Das M. Hypoxic activation of adventitial fibroblasts: role in vascular remodeling. Chest 122: 326S–334S, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Loop FT, Schaart G, Timmer ED, Ramaekers FC, van Eys GJ. Smoothelin, a novel cytoskeletal protein specific for smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol 134: 401–411, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao W, Firth AL, Sacks RS, Ogawa A, Auger WR, Fedullo PF, Madani MM, Lin GY, Sakakibara N, Thistlethwaite PA, Jamieson SW, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Identification of putative endothelial progenitor cells (CD34+CD133+Flk-1+) in endarterectomized tissue of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L870–L878, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi ES, Kim H, Ahn H, Strother J, Morris T, Masliah E, Hansen LA, Park KJ, Friedman PJ. Distribution of obstructive intimal lesions and their cellular phenotypes in chronic pulmonary hypertension. A morphometric and immunohistochemical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1577–1586, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang K, Rekhter MD, Gordon D, Phan SH. Myofibroblasts and their role in lung collagen gene expression during pulmonary fibrosis. A combined immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Am J Pathol 145: 114–125, 1994 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoia MC, D'Armini AM, Beccaria M, Corsico A, Fulgoni P, Klersy C, Piovella F, Vigano M, Cerveri I. Mid term effects of pulmonary thromboendarterectomy on clinical and cardiopulmonary function status. Thorax 57: 608–612, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]