Abstract

Muscle wasting in various catabolic conditions is at least in part regulated by glucocorticoids. Increased calcium levels have been reported in atrophying muscle. Mechanisms regulating calcium homeostasis in muscle wasting, in particular the role of glucocorticoids, are poorly understood. Here we tested the hypothesis that glucocorticoids increase intracellular calcium concentrations in skeletal muscle and stimulate store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) and that these effects of glucocorticoids may at least in part be responsible for glucocorticoid-induced protein degradation. Treatment of cultured myotubes with dexamethasone, a frequently used in vitro model of muscle wasting, resulted in increased intracellular calcium concentrations determined by fura-2 AM fluorescence measurements. When SOCE was measured by using calcium “add-back” to muscle cells after depletion of intracellular calcium stores, results showed that SOCE was increased 15–25% by dexamethasone and that this response to dexamethasone was inhibited by the store-operated calcium channel blocker BTP2. Dexamethasone treatment stimulated the activity of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2), and dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE was reduced by the iPLA2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL). In additional experiments, treatment of myotubes with the store-operated calcium channel inhibitor gadolinium ion or BEL reduced dexamethasone-induced increase in protein degradation. Taken together, the results suggest that glucocorticoids increase calcium concentrations in myocytes and stimulate iPLA2-dependent SOCE and that glucocorticoid-induced muscle protein degradation may at least in part be regulated by increased iPLA2 activity, SOCE, and cellular calcium levels.

Keywords: glucocorticoids, muscle, wasting

muscle wasting, mainly reflecting stimulated degradation of myofibrillar proteins, is commonly seen in patients with sepsis, severe injury, and cancer (24, 52). Loss of muscle mass also occurs in patients with muscular dystrophy (30, 31). In previous studies, we found evidence (4, 15, 79) that sepsis-induced muscle proteolysis was associated with increased uptake and tissue levels of calcium in skeletal muscle. Additional reports suggest that muscle atrophy caused by other catabolic conditions, including denervation, burn injury, and muscular dystrophy, is also associated with increased tissue concentrations of calcium (2, 3, 10, 17, 64, 73). These observations are significant because calcium is an important regulator of muscle protein balance and may link systemic catabolic responses to stimulated protein breakdown in skeletal muscle (16, 34, 50). The mechanisms regulating calcium entry and cellular levels of calcium in muscle-wasting conditions are not known.

Glucocorticoids are prominent mediators of muscle wasting in various catabolic conditions, including sepsis, burn injury, and starvation (13, 22, 63, 71). The influence of glucocorticoids on muscle calcium homeostasis, however, is not well understood. Previous reports concerning the effects of glucocorticoids on calcium entry and concentrations in myocytes provided contradictory results, with evidence of both increased (74) and reduced (41, 51, 57) influx and cytosolic concentrations of calcium in glucocorticoid-treated muscle cells.

Intracellular calcium levels are regulated by multiple mechanisms, including store-operated calcium entry (SOCE). In this mechanism, depletion of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or (in skeletal muscle) the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) activates store-operated calcium channels, resulting in increased influx of calcium into the cell (56). The regulation of SOCE is incompletely understood, but in one model second messengers termed “calcium influx factors” (CIFs) are released from calcium-depleted ER or SR and stimulate SOCE (60, 61). CIFs may function by activating calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) secondary to displacement of inhibitory calmodulin (CaM) from iPLA2 (67). Activated iPLA2 in turn generates lysophospholipids that activate store-operated calcium channels.

In the present study, we determined the effects of dexamethasone on calcium entry in cultured L6 myotubes, a rat skeletal muscle cell line (80). This experimental model was used because we (49, 76) and others (29) found previously that treatment of cultured myotubes with dexamethasone resulted in increased calpain- and ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent proteolysis, similar to the situation observed in muscle wasting caused by sepsis (14, 28, 72, 77). Cytosolic calcium concentrations were determined by fura-2 AM fluorescence, and SOCE was measured by using calcium “add-back” to muscle cells after depletion of calcium stores. Results suggest that dexamethasone increases SOCE in cultured L6 muscle cells and that this effect of dexamethasone is, at least in part, regulated by iPLA2 activity. In additional experiments, treatment of myotubes with the store-operated calcium channel blocker gadolinium ion (Gd3+) or with the iPLA2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL) reduced dexamethasone-induced protein degradation, suggesting that iPLA2-regulated SOCE may be involved in glucocorticoid-mediated muscle proteolysis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

l-[Ring-3,5-3H]tyrosine (40–60 Ci/mmol), Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Kit for enhanced chemiluminescence detection, and Solvable tissue solubilizer were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). Immun-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane used for Western blotting, 10% Ready Tris-HCl Mini-gels, and Precision Plus Protein Standards were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Primers and probes for quantitative real-time PCR were custom-synthesized by Biosearch Technologies (Novato, CA). TaqMan One Step PCR Master Mix Reagent Kits were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Kodak X-Omat blue film was from Eastman Kodak (Rochester, NY). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) was purchased from Mediatech (Herndon, VA). Penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin, digitonin, and fura-2 AM were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and all other chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tissue culture plasticware was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY).

Cell Cultures

Rat L6 skeletal muscle cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). L6 cells were grown and maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in a 10% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. Since the extent of myoblast fusion into myotubes declines with increasing passage, cells were used at passage 2 for all experiments to maintain the differentiation potential of the cultures. Cells grown to ∼60% confluence in T75 culture flasks were trypsinized and seeded into 10-cm culture dishes, 6- or 12-multiwell culture plates, or additional T75 flasks for experiments. The cells were grown in the presence of 10% FBS until they reached ∼60% confluence, at which time the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% FBS for the induction of differentiation into myotubes. During this time, the myoblasts fused to form elongated, multinucleated myotubes. After 7 days, the cultures were treated with 10 μM cytosine arabinoside for 3 days to remove any dividing myoblasts.

Measurement of Calcium Levels by Spectrofluorometry

Real-time measurement of intracellular free calcium levels.

Myoblasts, seeded onto collagen-coated glass coverslips (Fisher, catalog no. 08-774-387), were induced to differentiate into myotubes as described above. Myotubes were loaded with fura-2 AM (5 μM) in DMEM for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. Subsequently, coverslips were rinsed in dye-free DMEM, mounted into a perfusion chamber containing DMEM at room temperature, and then transferred to a microscope stage (Nikon Eclipse TE-2000-U). Simultaneous fluorescence measurements were obtained within individual myotubes by monochromator-based excitation, as described by Walsh et al. (75). Fura-2-loaded cells were excited alternately at 340 and 380 nm with a LPS 150 Photonics Polychrome IV system (Martinsried, Germany). Emitted light was collected at 520 ± 15 nm after alternating excitation. The ratio of these emission intensities provides an index of the free Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm. Digital images of myotubes were captured with a digital charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-ER). Images were processed with compatible software (Universal Imaging, Downington, PA) to yield background-corrected pseudocolor images reflecting the 340-nm to 380-nm ratio. Images were acquired every 10 s to minimize photobleaching. Contributions of autofluorescence were measured but were negligible because of the bright staining of cells.

Measurement of SOCE.

Pretreated myotubes cultured in T75 flasks were harvested by trypsinization, centrifuged, and then resuspended in buffer. Myotubes were loaded with fura-2 AM (3 μM) for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. The cells were divided into aliquots of ∼2 × 105 cells and placed on ice in the dark until ready for use. The individual aliquot to be used was incubated at 37°C for 5 min before each experiment. Cells were subsequently pelleted by brief centrifugation and then resuspended in nominally calcium-free buffer. The SR was emptied of calcium by adding 1 μM thapsigargin (TG) or 100 nM arginine vasopressin (AVP). Intracellular free calcium levels ([Ca2+]i) were monitored by measuring fura fluorescence at 505 nm with 340/380-nm dual wavelength excitation in a Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorometer (Jobin Yvon-Spex, Edison, NJ), as previously described (32). Cuvette temperatures were kept at 37°C with constant stirring. Calibration was performed at the end of each experiment by the addition of 100 μM digitonin to determine the maximum fluorescence ratio (RMAX) and then 15 mM EGTA to determine the minimum fluorescence ratio (RMIN). The autofluorescence of a sample cell suspension treated with 100 μM digitonin and 2 μM MnCl2 was subtracted from total fluorescence. The [Ca2+]i was then calculated from the 340-nm to 380-nm fluorescence ratio (Kd = 220 nM) as described by Grynkiewicz et al. (20). Dye leakage was trivial and had no influence on [Ca2+]i calculations by our methods. The order of study of cell aliquots was alternated to avoid bias related to duration of dye loading or time of cell study. Calcium entry currents were measured by the readdition of 1.8 mM external calcium to cells stimulated in a calcium-free environment.

Preparation of Total Cell Lysates

Total cell lysates were prepared by harvesting the myotubes directly in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Nonidet P-40) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). After the lysates were scraped into Eppendorf tubes, the samples were briefly sonicated with a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, model 100) followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Concentrations of soluble proteins in the supernatants of the total cell lysates were determined by using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) with bovine serum albumin as standard. Cell lysates were stored at −80°C until analyzed.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed to determine protein levels of iPLA2 in dexamethasone-treated myotubes. Aliquots containing 50 μg of cellular protein, prepared as described above, were boiled in Laemmli sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 10% Ready Tris-HCl Gels and then transferred electrophoretically at 2,000 mA for 1 h in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3, containing 20% methanol) onto Immun-Blot PVDF membranes at 4°C. The membranes were blocked with TTBS buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 130 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated overnight with a 1:500 dilution of iPLA2 antibody (goat polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide mapping within an internal region of rat iPLA2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubation with the primary antibody, the membranes were washed with TTBS three times and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a donkey anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:10,000 dilution. After an additional three washes with TTBS, immunoreactive protein bands were visualized with the Western Lightning Kit for enhanced chemiluminescence followed by exposure to Kodak X-Omat blue film.

The identity of the iPLA2 band on the Western blots was confirmed by including precision molecular weight standards during electrophoresis and by performing competition studies using a blocking peptide. iPLA2 antibody was preincubated with a specific blocking peptide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS for 2 h with gentle mixing at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with this “blocked” antibody overnight, followed by processing and analysis as described above. Blots were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions and reprobed with α-tubulin antibody to confirm equal loading of lanes.

Determination of iPLA2 mRNA

iPLA2 mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. Rat primers for iPLA2 (gene accession no. NM_001005560) were designed with Primer Express 1.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Cellular RNA was extracted from cultured myotubes grown in six-multiwell plates by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method (9) with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). Multiplex real-time PCR was performed for quantitation of mRNA expression with simultaneous amplification of 18S RNA as endogenous controls to normalize the mRNA concentrations. TaqMan analysis using the One Step PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit and subsequent calculations were performed with an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). For each sample, 100 ng of total RNA was subjected to real-time PCR (in duplicate) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The sequences of the primer oligonucleotides and the double-labeled TaqMan oligonucleotide probe for iPLA2 mRNA were the following: 5′-CCT CGC TGT ACC CCA AAC AT-3′ (forward); 5′-CCG CCA TAC TAA CTG GTC TGC-3′ (reverse); 5′-AAC CTG AAG CCG CCC ACC CAG-3′ (probe). Three or four individual wells were used for each experimental group. mRNA levels in control myotubes were arbitrarily set to 1.0.

Measurement of PLA2 Activity

The enzymatic activity of iPLA2 was measured with a commercially available assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Myotubes grown on 10-cm culture dishes were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone. Cells were harvested with a cell scraper in PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in cold buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and sonicated for 5 s. Cell homogenates were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter Devices [30,000 nominal molecular weight limit (NMWL)] and centrifuged at 3,000 g (4°C) to concentrate the samples. The iPLA2 activity was determined by first measuring total PLA2 activity. Samples were incubated with the PLA2 substrate arachidonoyl thio-phosphatidylcholine for 1 h at room temperature in calcium-containing buffer in the absence or presence of the specific iPLA2 inhibitor BEL (5 μM final concentration). The reaction was stopped by adding 5,5′-dithiobis(2-dinitrobenzoic acid)-EGTA for 5 min, and the absorbance was subsequently determined at 414 nm with a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The iPLA2 activity was calculated as the portion of total PLA2 activity that was inhibited by BEL. After PLA2 activity measurements, aliquots of the supernatant were saved for protein determinations. Phospholipase activities were expressed as nanomoles per minute per milligram of protein. Because inhibition of PLA2 activity with BEL does not distinguish between iPLA2β and iPLA2γ activity, additional experiments were performed with the selective iPLA2β inhibitor S-BEL or the selective iPLA2γ inhibitor R-BEL as described by Jenkins et al. (33). The assay was performed as described above except that BEL was substituted by S-BEL (5 μM) or R-BEL (5 μM) (Cayman Chemical).

Measurement of Protein Degradation

Rates of protein degradation were determined by measuring the release of TCA-soluble radioactivity from proteins prelabeled with [3H]tyrosine as described previously (29, 77). In short, myotubes were labeled with 1.0 μCi/ml l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine for 48 h in DMEM containing 2% FBS. Cells were then treated for 24 h with dexamethasone in the absence or presence of inhibitors in DMEM containing 2 mM unlabeled tyrosine. After treatment, the culture medium was transferred into a microcentrifuge tube containing 100 μl of bovine serum albumin (10 mg/ml) and TCA was added to a final concentration of 10% (wt/vol). Samples were incubated at 4°C for 1 h, followed by centrifugation for 5 min. The supernatant was used for determination of TCA-soluble radioactivity. The protein precipitates were dissolved with a tissue solubilizer (Solvable). Cell monolayers were solubilized with 0.5 M NaOH containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Radioactivity in the cell monolayer and TCA-soluble and -insoluble fractions were measured with a Packard TRI-CARB 1600 TR liquid scintillation analyzer. Protein degradation was expressed as the percentage of protein degraded over the 24-h period and was calculated as 100 times the TCA-soluble radioactivity in the medium divided by the TCA-soluble plus the TCA-insoluble radioactivity in the medium plus the cell layer (i.e., myotube) radioactivity (29, 76).

Small Interfering RNA Gene Silencing

Rat PLA2G6 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (ON-TARGET plus SMART pool) and control siRNA (NON-TARGET plus SMART pool), purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), were used to silence gene expression of iPLA2. It should be noted that it is possible that the siRNA construct used here downregulated both the long and short isoforms of iPLA2. Myotubes grown in six-multiwell culture plates were transfected with 200 nM PLA2G6 siRNA or control siRNA with DharmaFECT 3 Reagent (4%) in DMEM without FBS or antibiotics for 24 h. After transfection, cells were used for measurements of iPLA2 mRNA levels and SOCE.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t-test or by ANOVA followed by Tukey's or Student-Newman-Keuls test, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Most experiments were repeated at least three times to provide evidence of reproducibility.

RESULTS

Dexamethasone Increases Intracellular Calcium Concentrations in L6 Myotubes

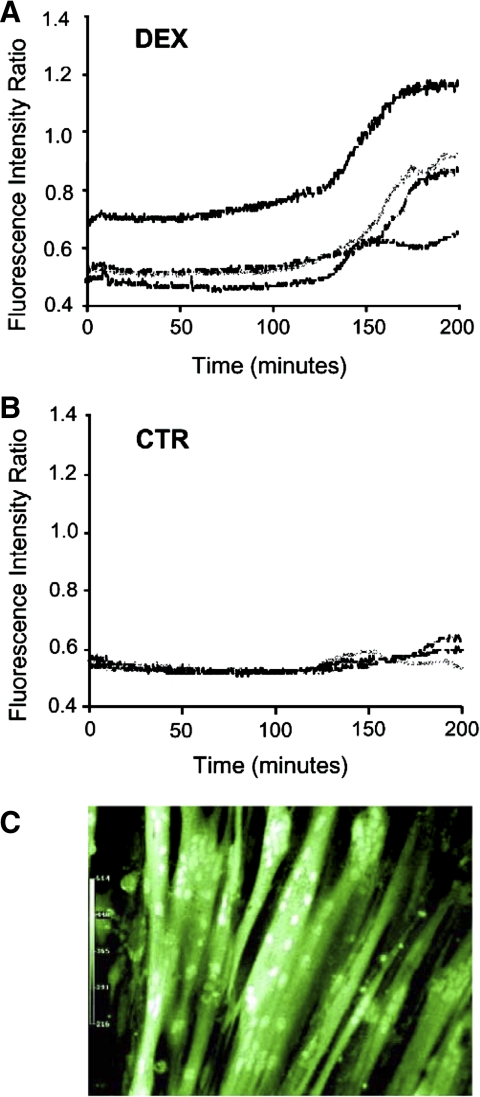

In initial experiments, we determined intracellular calcium concentrations during ongoing treatment of cultured L6 myotubes with dexamethasone by measuring fura-2 fluorescence. In these experiments, L6 myotubes were cultured on collagen-coated coverslips to allow for the continual measurement of calcium concentrations after loading of the myotubes with fura-2. Treatment of the L6 myotubes with 1 μM dexamethasone resulted in increased intracellular calcium concentrations (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the intracellular calcium levels remained stable in control myotubes during the same period of time (Fig. 1B). The increase in calcium concentrations was noted after treatment of the myotubes with dexamethasone for ∼2 h and reached an apparent maximum after 3 h. Because this experiment required culturing the myotubes on special collagen-coated coverslips, rather than in regular culture wells, it was important to ascertain that this culture environment did not affect myotube morphology and viability. Cell rounding or detachment did not occur in control or dexamethasone-treated myotubes cultured on collagen-coated coverslips, and fluorescent images showed a robust formation of normal-looking, differentiated myotubes (Fig. 1C), supporting the validity of this experimental approach to determine intracellular calcium levels during treatment with dexamethasone.

Fig. 1.

Effect of dexamethasone on cytosolic calcium concentrations in cultured L6 myotubes. L6 myotubes were cultured on collagen-coated glass coverslips and were loaded with fura-2 AM (5 μM). Myotubes were then treated with 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex; A) or observed for the same period of time in the absence of dexamethasone [control (CTR); B]. Fluorescence measurements were obtained continuously within individual myotubes for 200 min at 520 nm after 340/380-nm dual excitation. Each line represents measurements from a single myotube. C: digital images of L6 myotubes allowed to differentiate on collagen-coated glass coverslips.

SOCE Regulates Intracellular Calcium Levels in L6 Myotubes

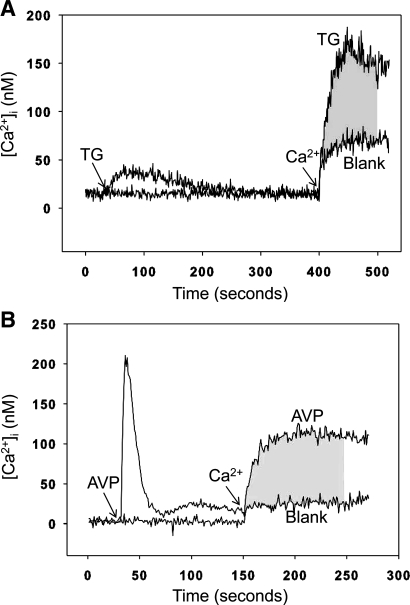

One mechanism by which intracellular calcium levels can be increased is via stimulated SOCE (56). We next wanted to determine whether increased calcium levels in dexamethasone-treated myotubes are associated with increased SOCE. To examine that question, we first established conditions allowing for analysis of SOCE in cultured L6 myotubes. Differentiated myotubes were harvested, suspended in culture medium, and loaded with fura-2. The myotubes were then resuspended in calcium-free medium, and TG or AVP was used to empty the SR. Calcium was then added back to the system at a concentration of 1.8 mM. TG depletes calcium stores by inhibiting sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase (SERCA) in muscle cells (35). Vasopressin depletes calcium stores by a G protein-coupled receptor mechanism that activates the SR inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor (21). Although AVP may be less established than TG for use in muscle cells, recent studies suggest that vasopressin exerts effects in skeletal muscle (53). Treatment of the suspended myotubes with TG resulted in increased cytosolic calcium levels consistent with release of calcium from the SR stores into the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). When calcium was added back to the system after depletion of the calcium stores, a rapid increase in cytosolic calcium concentrations (influx) was noted, consistent with SOCE. This increase was substantially higher than the “blank” increase noted after addition of calcium without pretreatment with TG. The difference in the influx area under the curve (AUC) between TG-treated myotube suspensions and the blank was calculated during 100 s after addition of calcium and was used as a measure of SOCE. When AVP was used to empty the SR in the suspended myotubes, the release of calcium from the SR stores into the cytoplasm was more transient and AVP-induced SOCE was calculated as described for TG-induced SOCE (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the results in Fig. 2 illustrate how SOCE was calculated in the present study and suggest that calcium homeostasis in cultured L6 myotubes is at least in part regulated by SOCE, which is consistent with previous reports showing activation of SOCE when SR calcium stores were depleted in skeletal muscle cells (7, 37, 45).

Fig. 2.

Calculation of store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) in cultured L6 myotubes as area under the curve (AUC). L6 myotubes were loaded with fura-2 AM (3 μM) and suspended in calcium-free buffer. The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) calcium store was depleted with 1 μM thapsigargin (TG; A) or 100 nM arginine vasopressin (AVP; B), followed by the addition of calcium (1.8 mM) to the suspension buffer as indicated. Myotubes in which the SR calcium store was not depleted served as blank. Cytosolic free calcium levels ([Ca2+]i) were monitored by measuring fura fluorescence at 505 nm with 340/380-nm dual-wavelength excitation. The difference in influx between TG- or AVP-treated myotubes and the blank was calculated as AUC during 100 s after addition of calcium (shaded area) and was used as a measure of SOCE.

The baseline intracellular calcium levels observed in Fig. 2 were lower than is commonly reported in most cell types, including muscle cells. This finding may reflect inaccurate calibration of fura-2 as described in a recent report (75) and illustrates the fact that the relative changes in calcium levels caused by store emptying and readdition of calcium are more important than the absolute values. Because SOCE was calculated as the AUC, the importance of the absolute levels was also minimized (assuming that the baseline and the tracing after readdition of calcium were shifted upward or downward to the same extent).

Of note, the method used to study SOCE differed from the experiments depicted in Fig. 1. Thus, when SOCE was measured, we used aliquots of suspended myotubes that had been harvested by trypsinization, centrifuged, and resuspended in buffer. This experimental design allowed for several in vitro treatments (treatments with TG or AVP followed by readdition of calcium in the absence or presence of various inhibitors) and measurement of fluorescence over short periods of time (minutes) in multiple samples from the same myotubes. Although this method offered the advantage of high throughput in our experiments, potential limitations need to be considered. For example, it is possible that cells sustained mechanical injury during the process of harvesting and subsequent preparation. The fact that the cells responded to TG and AVP and readdition of calcium in a manner similar to what has been described in many other cell types that did not go through the same mechanical procedures as the myotubes in the present study suggests, however, that whatever injury the cells sustained during harvesting and subsequent preparation did not preclude reproducible measurements of SOCE.

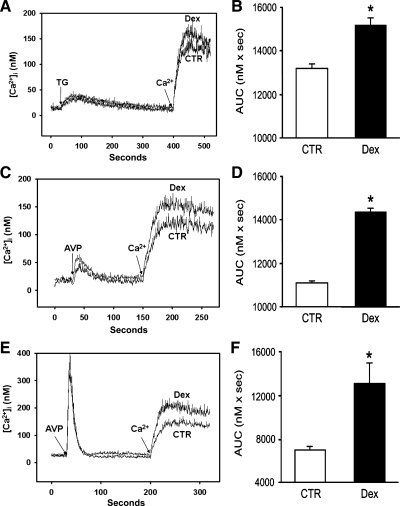

Treatment of L6 Myotubes with Dexamethasone Stimulates SOCE

We next wanted to determine the influence of dexamethasone on SOCE in cultured L6 myotubes. After treatment of the myotubes with 1 μM dexamethasone for 24 h, SOCE, calculated in suspended myotubes as the AUC during 100 s after readdition of 1.8 mM calcium as described in Fig. 2, was increased, and this effect of dexamethasone was noted when either TG or AVP was used to empty the calcium stores. Dexamethasone increased TG-induced SOCE by ∼15% (Fig. 3, A and B) and AVP-induced SOCE by ∼25% (Fig. 3, C and D). The release of calcium from the intracellular stores in the suspended myotubes by TG or AVP was not affected by the dexamethasone treatment, as indicated by similar cytosolic calcium levels after addition of the drugs to dexamethasone-treated and control myotubes. Because dexamethasone treatment stimulated AVP-induced SOCE more than TG-induced SOCE (Fig. 3, B and D), AVP was used to induce SOCE in the remaining experiments in the present study.

Fig. 3.

Effect of dexamethasone on TG- and AVP-induced SOCE in L6 myotubes and myoblasts. Cultured L6 myotubes or myoblasts were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or corresponding concentration of solvent (0.1% ethanol; CTR). After treatment with dexamethasone for 24 h, myotubes or myoblasts were suspended and loaded with fura-2 AM (3 μM). Myotube SR calcium stores were depleted with TG (1 μM; A and B) or AVP (100 nM; C and D) in calcium-free suspension medium, followed by addition of 1.8 mM calcium. A and C depict typical tracings, and B and D represent calculations of SOCE. E and F: AVP-induced SOCE in L6 myoblasts after 24 treatment with dexamethasone (1 μM) or corresponding concentration of solvent (0.1% ethanol). SOCE was calculated as AUC as described in Fig. 2. Results in B, D, and F are means ± SE with n = 3–5 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

Although the dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE noted here may seem relatively small, it should be pointed out that the results represent “snapshots” in cells studied after 24 h of dexamethasone treatment. If a similar effect of dexamethasone is present during a period of the treatment (as indicated by time course experiments below), the “cumulative” effects on intracellular calcium levels may be greater than indicated by the single measurement of SOCE after 24 h.

Because other studies suggest that the influence of glucocorticoids on calcium homeostasis may be different in undifferentiated and differentiated cultured muscle cells (74), we next determined the effect of dexamethasone on SOCE in L6 myoblasts. Similar to the response in L6 myotubes, treatment of L6 myoblasts with dexamethasone resulted in increased AVP-induced SOCE (Fig. 3, E and F).

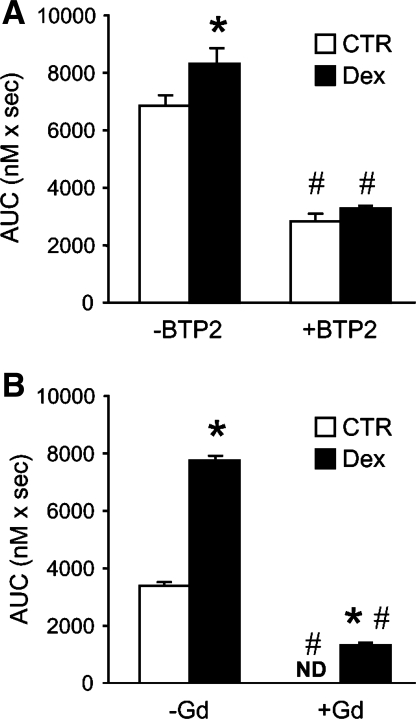

To further test whether the increase in cellular calcium levels after treatment with dexamethasone reflected increased SOCE, myotubes were treated with the store-operated calcium channel blocker BTP2 (26, 84). When suspended myotubes were exposed to BTP2, basal SOCE was reduced and the dexamethasone-induced increase in calcium entry was abolished (Fig. 4A). Because BTP2 may not be completely specific in its effects on SOCE, we performed an additional experiment using another SOCE inhibitor, Gd3+. As shown in Fig. 4B, the presence of 1 μM Gd3+ blocked basal SOCE and effectively inhibited SOCE in dexamethasone-treated myotubes. Taken together, the results in Fig. 4 support the interpretation that the dexamethasone-stimulated increase in calcium entry is at least in part SOCE dependent.

Fig. 4.

Effects of BTP2 and Gd3+ on SOCE in control and dexamethasone-treated myotubes. Cultured myotubes were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or corresponding concentration of solvent (0.1% ethanol). After treatment, myotubes were suspended and AVP-induced SOCE was measured in the absence or presence of 25 μM BTP2 (A) or 1 μM Gd3+ (B). AVP-induced SOCE was calculated as AUC during 100 s as described in Fig. 2. Results are means ± SE with n = 3–5 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control (no dexamethasone); #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding group without BTP2 or Gd3+. ND, not detectable.

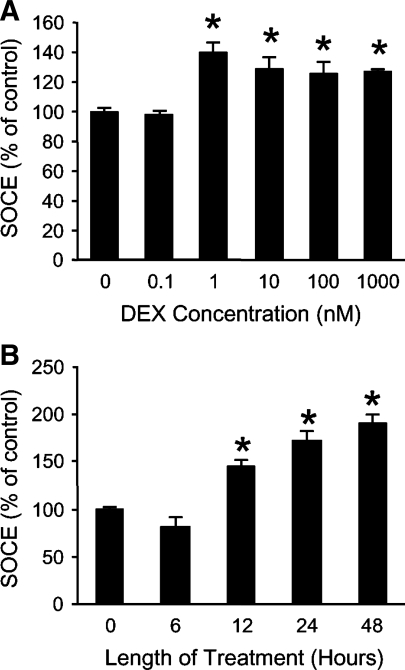

To better characterize the influence of dexamethasone on SOCE in muscle cells, cultured L6 myotubes were treated with different concentrations of dexamethasone for varying periods of time. AVP-induced SOCE was increased after 24-h treatment with 1 nM dexamethasone, with no additional increase noted at higher concentrations (Fig. 5A). It should be noted that 1 μM dexamethasone was used in most experiments in the present study because we (49, 76) and others (12, 29, 39, 62) used this (or higher) concentration in previous experiments in which dexamethasone-stimulated protein degradation was studied in cultured myotubes. However, similar to SOCE, in a recent study, we found (49) that protein degradation was stimulated by dexamethasone concentrations as low as 1 nM in cultured myotubes, suggesting that there is an association between SOCE and protein degradation even at low dexamethasone concentrations. Although 1 μM dexamethasone is a high concentration (corresponding to 25 μM corticosterone, the natural glucocorticoid in rodents), it was important to use this concentration in the present study to make experiments reflect glucocorticoid-induced muscle catabolism (22) and to make it possible to compare results with multiple previous studies (12, 29, 39, 49, 62, 76). Various aspects of treating cultured myotubes with different concentrations of dexamethasone or corticosterone were examined in detail recently (49). When L6 myotubes were treated with 1 μM dexamethasone for different lengths of time, SOCE was increased in a time-dependent fashion, with the earliest increase noted after treatment for 12 h (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of treatment of L6 myotubes with different concentrations of dexamethasone for different periods of time on SOCE. A: cultured myotubes were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of dexamethasone, followed by measurement of AVP-dependent SOCE in suspended myotubes as AUC during 100 s after addition of 1.8 mM calcium to fura-2 AM-loaded suspended myotubes. Results are expressed as % of control (SOCE in myotubes treated for 24 h with solvent) and are given as means ± SE with n = 6 in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 nM dexamethasone. B: cultured L6 myotubes were treated with 1 μM dexamethasone for different periods of time, followed by measurement of SOCE as described above. Results are means ± SE with n = 3–5 in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. CTR (no treatment with dexamethasone).

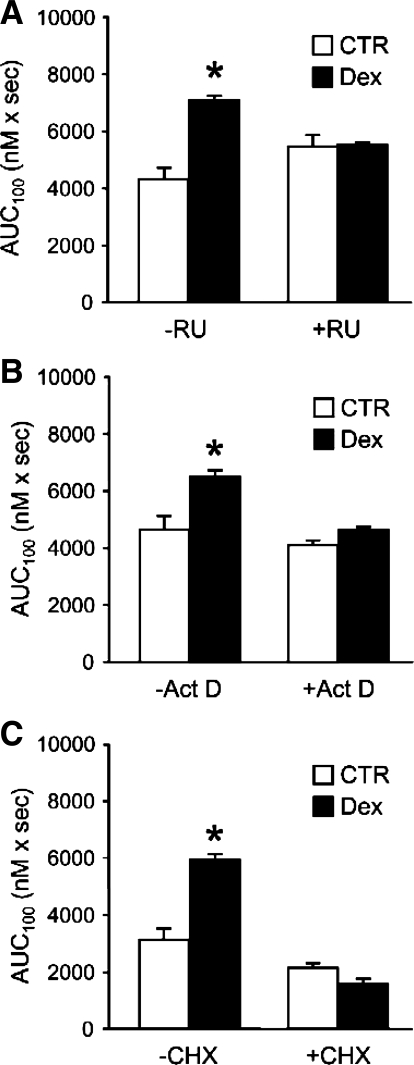

Stimulation of SOCE by Dexamethasone in L6 Myotubes Is Glucocorticoid Receptor Dependent

Although most effects of glucocorticoids are glucocorticoid receptor (GR) dependent (44), there is evidence that some metabolic effects of glucocorticoids are GR independent (43, 69). To examine the role of the GR in dexamethasone-induced SOCE, we next treated myotubes with 1 μM dexamethasone for 24 h in the absence or presence of the GR antagonist RU38486 (59). The dexamethasone-stimulated increase in SOCE was prevented by RU38486 (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the increase in SOCE caused by dexamethasone required ligand binding to and activation of the GR.

Fig. 6.

Effects of RU38486 (RU), actinomycin D (Act D), and cycloheximide (CHX) on SOCE in dexamethasone-treated L6 myotubes. Cultured myotubes were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or corresponding concentration of solvent (ethanol) in the absence or presence of 1 μM RU (A), 1 μg/ml Act D (B), or 10 μg/ml CHX (C). AVP-induced SOCE was determined as AUC during 100 s (AUC100) after addition of 1.8 mM calcium to fura-2-loaded myotubes suspended in calcium-free medium as described in Fig. 2. Results are means ± SE with n = 6 in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding control group.

The activated GR functions as a transcription factor, and most effects of glucocorticoids therefore reflect activation of gene transcription (25, 44). To test the role of transcriptional activation in dexamethasone-induced SOCE stimulation, myotubes were treated with dexamethasone in the presence of the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D. As can be seen in Fig. 6B, 1 μg/ml of actinomycin D abolished the effect of dexamethasone on SOCE. When myotubes were treated with dexamethasone in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (10 μg/ml), the increase in SOCE was also prevented (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the dexamethasone-induced SOCE was dependent on de novo protein synthesis. Taken together, the results in Fig. 6 suggest that the dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE required binding of the hormone to the GR and production of a protein or proteins, the synthesis of which was regulated at the transcriptional level.

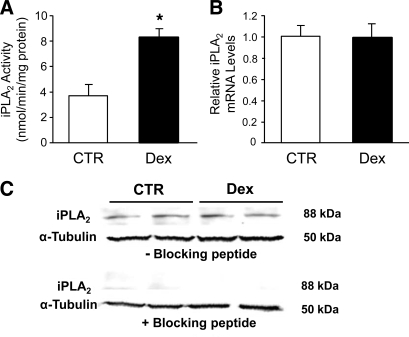

Dexamethasone-Stimulated SOCE Is iPLA2 Dependent

Recent studies suggest that SOCE is under the control of iPLA2 in different cell types (7, 27, 46, 61, 67, 68, 82), but it is not known whether glucocorticoid-induced calcium entry is regulated via this mechanism. Here, we examined the potential role of iPLA2 in dexamethasone-stimulated SOCE by first measuring iPLA2 activity in control and dexamethasone-treated myotubes and found that dexamethasone treatment resulted in a 2.5-fold increase in iPLA2 activity (Fig. 7A). Of note, the method used here to determine iPLA2 activity (using BEL in the assay as described in experimental procedures) does not discriminate between iPLA2β and iPLA2γ activity (33). To test the role of iPLA2β and iPLA2γ in dexamethasone-induced activity, we used the selective iPLA2β and iPLA2γ inhibitors S-BEL and R-BEL, respectively. With these inhibitors basal iPLA2β activity was not detectable in control myotubes, whereas after treatment with dexamethasone for 24 h the iPLA2β activity was increased to 1.22 ± 0.21 nmol·min−1·mg protein−1 (n = 6; P < 0.05 vs. control). Interestingly, iPLA2γ activity was not detectable in control or dexamethasone-treated myotubes. Thus the increase in iPLA2 activity shown in Fig. 7A most likely reflected stimulated iPLA2β activity.

Fig. 7.

Effect of dexamethasone on the activity and expression of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) in L6 myotubes. Cultured L6 myotubes were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or corresponding concentration (0.1%) of ethanol (CTR). A: iPLA2 activity determined as described in experimental procedures. Results are means ± SE with n = 5 in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. control. B: iPLA2 mRNA levels determined by real-time PCR and normalized to 18S mRNA. Results are expressed as arbitrary units, with mRNA levels in control myotubes (no dexamethasone treatment) set to 1.0. Results are means ± SE with n = 4 in each group. C: iPLA2 protein levels determined by Western blotting performed in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of a specific blocking peptide. Molecular masses of the bands given on right of blots were determined from a molecular weight ladder included during electrophoresis.

Increased enzyme activity may reflect increased abundance of the enzyme or an increase in specific activity. To determine whether the stimulated iPLA2 activity noted in the present experiments was associated with increased amounts of the enzyme, we next examined the expression of iPLA2 in dexamethasone-treated myotubes by Western blotting and real-time PCR. Results from these experiments showed that iPLA2 protein and mRNA levels were not affected by dexamethasone (Fig. 7, B and C). Therefore, the increased iPLA2 activity in dexamethasone-treated myotubes probably reflected an increase in iPLA2-specific activity rather than increased abundance of the enzyme.

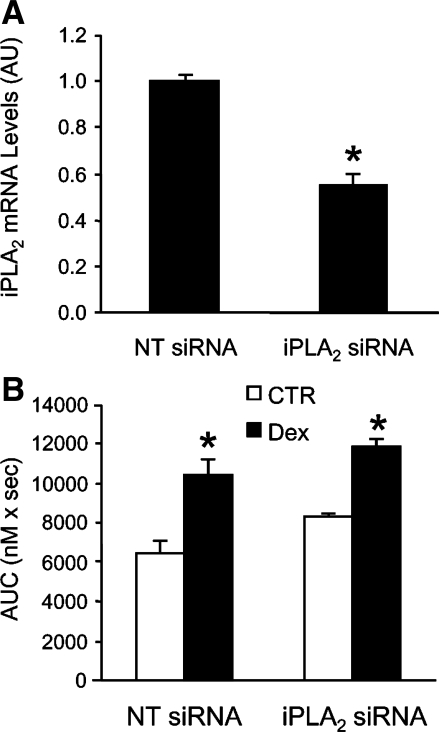

To further test whether the overall expression of iPLA2 influences SOCE in dexamethasone-treated myotubes, we downregulated iPLA2 levels, using siRNA gene silencing. When myotubes were transfected with iPLA2 siRNA, the effectiveness of the transfection was confirmed by an ∼40% reduction of iPLA2 mRNA levels (Fig. 8A). This degree of downregulation is similar to that in previous experiments in which siRNA constructs were used to silence genes in cultured myotubes (81). Of note, myotubes were transfected with iPLA2 siRNA for 24 h in the present experiments, and it is possible that an extended period of siRNA treatment would have resulted in a greater downregulation of iPLA2. Indeed, in a recent study in which cultured prostate cancer cells were transfected with iPLA2 siRNA, iPLA2 mRNA levels were reduced by 50–56% after 48 h and by 70–79% after 72 h (54).

Fig. 8.

Effect of iPLA2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) on iPLA2 expression and SOCE in cultured L6 myotubes. A: cultured L6 myotubes were transfected with iPLA2 siRNA (200 nM) or corresponding concentration of nontargeting (NT) control siRNA for 24 h. After transfection, mRNA levels for iPLA2 were determined by real-time PCR and were normalized to 18S mRNA. Results are expressed as arbitrary units (AU), with mRNA levels in myotubes transfected with NT siRNA set to 1.0. Results are means ± SE with n = 4 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. NT siRNA. B: L6 myotubes that had been transfected for 24 h with NT or iPLA2 siRNA were treated for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone or corresponding concentration of solvent, followed by measurement of AVP-induced SOCE. SOCE was determined as described in Fig. 2 as AUC during 100 s after addition of calcium (1.8 mM) to fura-2-loaded myotubes suspended in calcium-free medium. Results are means ± SE with n = 3–5 in each group. *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding control group (no dexamethasone treatment).

The dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE was similar in myotubes treated with nontargeting (scrambled) or iPLA2-specific siRNA (Fig. 8B), supporting the concept that dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE did not depend on the expression of iPLA2 but rather reflected an increase in specific enzyme activity. This interpretation needs to be done with caution, however, because it is possible that an even greater downregulation of iPLA2 than observed here (see Fig. 8A) may have resulted in a reduction of dexamethasone-induced SOCE. However, the fact that there was no trend toward reduced SOCE, despite the 40–50% reduction of iPLA2 expression, and the fact that dexamethasone did not increase iPLA2 mRNA or protein levels together suggest that dexamethasone-induced SOCE does not depend on the abundance of iPLA2.

Because these results suggest that dexamethasone increased iPLA2 activity (mainly reflecting increased iPLA2β activity), we next wanted to test whether inhibition of iPLA2 activity during treatment with dexamethasone would prevent the dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE. When cultured myotubes were treated with BEL, SOCE was reduced under both basal and dexamethasone-treated conditions (Table 1). When the BEL-induced inhibition of SOCE was calculated in myotubes cultured in the absence or presence of dexamethasone, the “BEL-dependent” SOCE was 51% higher in dexamethasone-treated myotubes (Table 1). This finding further supports a role of iPLA2 activation in dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE.

Table 1.

SOCE in cultured L6 myotubes after treatment for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone in absence or presence of 1 μM BEL

| −Dex | +Dex | Dex-Induced Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −BEL | 6,498 ± 322 | 9,062 ± 1,021† | |

| +BEL | 4,800 ± 214* | 6,494 ± 99*† | |

| BEL-dependent SOCE | 1,698 | 2,568 | +51% |

Results are mean ± SE store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) [area under the curve during 100 s after addition of calcium (AUC100; nM×s); n = 8 in each group] in cultured L6 myotubes after treatment for 24 h with 1 μM dexamethasone (Dex) in the absence or presence of 1 μM bromoenol lactone (BEL). The difference in SOCE between myotubes treated in the absence and presence of BEL was calculated as “BEL-dependent SOCE.” Almost identical results were observed in a repeat experiment.

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding −BEL group;

P < 0.05 vs. corresponding −Dex group.

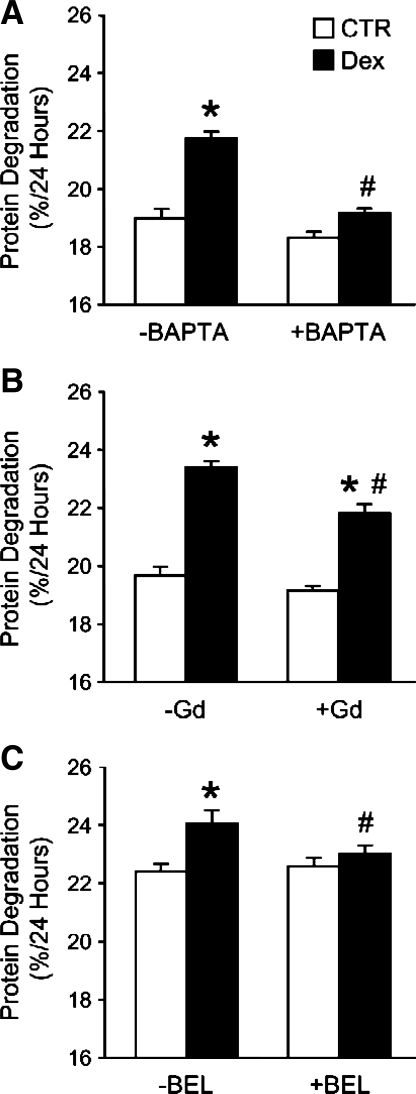

Dexamethasone-Stimulated Protein Degradation in L6 Myotubes Is Calcium- and SOCE Dependent and May Be Regulated by iPLA2

In previous studies from our (49, 76) and other (12, 29, 39, 62) laboratories, treatment of cultured myotubes with dexamethasone resulted in stimulated protein degradation, reflecting the important role of glucocorticoids as mediators of protein breakdown in various muscle-wasting conditions (13, 22, 52, 63, 71). Here, we tested the potential role of calcium and SOCE in dexamethasone-induced protein degradation in cultured L6 myotubes. When myotubes were treated with the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA, the dexamethasone-induced increase in protein degradation was inhibited, supporting a role of calcium in the response to dexamethasone (Fig. 9A). To test whether SOCE may be involved in the dexamethasone-induced protein degradation, myotubes were exposed to the store-operated calcium channel blocker Gd3+ during the 24-h dexamethasone treatment period. The dexamethasone-induced increase in protein degradation was blunted by 100 μM Gd3+, suggesting that the increase in protein degradation was, at least in part, regulated by SOCE (Fig. 9B). Basal protein degradation rates were not affected by Gd3+ in this experiment. No effects on dexamethasone-stimulated protein degradation were noted at lower Gd3+ concentrations (not shown), which was apparently different from the inhibition of SOCE by 1 μM Gd3+ (see Fig. 4B). It is important to point out, however, that the effects of Gd3+ on SOCE were examined during a short time (minutes) after addition of Gd3+ to suspended myotubes, whereas when protein degradation was measured, Gd3+ was added to a confluent layer of myotubes in culture wells and was present for 24 h. It is possible that higher concentrations of Gd3+ are needed in a confluent myotube layer than in suspended myotubes. It is also possible that “acute” effects of Gd3+ are induced by lower concentrations than those needed for a more protracted and sustained effect. Regardless of the potential reasons why different concentrations of Gd3+ were needed to inhibit dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE and protein degradation, the effects of Gd3+ on protein degradation observed here need to be interpreted with caution because of potential nonspecific effects of the drug at high concentrations.

Fig. 9.

Effects of BAPTA, Gd3+, and bromoenol lactone (BEL) on dexamethasone-induced protein degradation in cultured L6 myotubes. Protein degradation was determined as release of TCA-soluble radioactivity during 24 h in the absence or presence of 1 μM dexamethasone from proteins prelabeled with [3H]tyrosine and expressed as %/24 h. Dexamethasone treatment was performed in the absence or presence of 20 μM BAPTA (A), 100 μM Gd3+ (B), or 1 μM BEL (C). Results are means ± SE with n = 6 for each group. *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding control (no dexamethasone) group; #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding dexamethasone group.

Next, we treated myotubes with dexamethasone in the absence or presence of the iPLA2 inhibitor BEL and found that the dexamethasone-induced increase in protein degradation was almost completely abolished when myotubes were exposed to 1 μM BEL (Fig. 9C), the same concentration of BEL that inhibited SOCE (compare with Table 1).

Taken together, the results in Fig. 9 support an important role for calcium in glucocorticoid-induced muscle proteolysis and suggest that dexamethasone-induced protein degradation in cultured L6 myotubes may at least in part be regulated by SOCE and iPLA2 activity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, treatment of cultured L6 myotubes with dexamethasone resulted in stimulated SOCE and increased cytoplasmic calcium levels. The dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE was associated with increased iPLA2 activity and was reduced by the iPLA2 inhibitor BEL, suggesting that the increase in SOCE was at least in part regulated by iPLA2. Furthermore, our results suggest that the effect of dexamethasone on SOCE was GR dependent and required de novo protein synthesis regulated at the transcriptional level.

It should be noted that although dexamethasone-treated myotubes were used in the present study to examine glucocorticoid-regulated metabolic changes, important differences exist between dexamethasone and naturally occurring glucocorticoids, in particular with regard to the metabolism of the hormones. The action of glucocorticoids in peripheral tissues are in part determined by the enzymes 11β-hydrosteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) and type 2 (11β-HSD2) (36). Thus 11β-HSD1 catalyzes the conversion of inactive 11-dehydrocorticosterone (cortisone in humans) to the active corticosterone (cortisol in humans), whereas 11β-HSD2 does the opposite. Interestingly, there is evidence that the influence of the 11β-HSD system on dexamethasone is different from the effects on natural glucocorticoids. For example, 11β-HSD2 actively catalyzes the oxidoreduction of 11-dehydrodexamethasone to active dexamethasone but does not oxidoreduce cortisone to cortisol (11). In addition, there is recent evidence that the 11-dehydro form of dexamethasone (generated by 11β-HSD2) is biologically active (as opposed to the 11-dehydro form of natural glucocorticoids) (18). Finally, dexamethasone may upregulate the expression and activity of 11β-HSD2 (70), further supporting the notion that there are significant differences between dexamethasone and natural glucocorticoids with regard to 11β-HSD2-regulated metabolism of the hormones and their influence on the 11β-HSD system.

An interesting observation in the present study was the different time courses in our initial experiment (showing a lag time of 2–3 h before intracellular calcium levels increased during ongoing dexamethasone treatment) and the experiments in which SOCE was measured (showing a lag time of 12 h between start of dexamethasone treatment and increased SOCE). The most likely explanation for this observation is that the results from the different experiments reflected different mechanisms of calcium entry. Thus results in our initial experiments seem to reflect a relatively acute response, whereas results from experiments in which SOCE was measured seem to reflect a more subacute response, possibly reflecting iPLA2-dependent SOCE. Of note, our initial experiment did not measure SOCE since the intracellular stores were not depleted. Although the mechanism of the acute response observed in our initial experiment is not known at present, it is possible that dexamethasone-induced changes in Na+ transport and concentrations and in Na+/Ca2+ exchange were involved (55). In a previous study, Na+ transport was altered in catabolic muscle from rats with sepsis (47), lending support to the concept that changes in calcium and sodium homeostasis may be connected in muscle wasting. Regardless of the mechanism involved, the present observations are important because they suggest that glucocorticoids can increase muscle calcium uptake through different mechanisms.

Another important aspect of the present experiments that needs to be taken into account when the results are interpreted is the fact that the medium in which the myotubes were cultured contained FBS. Therefore, it is possible that the effects of dexamethasone on SOCE and protein degradation were influenced by other components present in the serum. The presence of thyroid hormone may be of particular interest because recent studies suggest that the effects of dexamethasone in cultured myotubes may be potentiated by thyroid hormone (62). In addition, we found previously that muscle protein breakdown during sepsis may at least in part be regulated by thyroid hormones (23), although glucocorticoids play a more prominent role in mediating catabolic effects in skeletal muscle (22). Because FBS was present in the medium of both control and dexamethasone-treated myotubes, it is less likely that the results of dexamethasone treatment were influenced by thyroid hormone (or other factors) in the medium, although it cannot be ruled out that the effects of dexamethasone were potentiated by the presence of thyroid hormone.

It should be noted that although the present and other studies (7, 37, 40, 45) are consistent with SOCE in skeletal muscle cells, the influence of glucocorticoids on muscle calcium entry and concentrations has been examined only in a few previous studies, with apparently conflicting results (41, 51, 57, 74). The present finding of increased calcium entry and concentrations in muscle cells treated with dexamethasone is consistent with a report by Vandebrouck et al. (74). In that study, treatment of cultured human muscle cells with methylprednisolone resulted in a 30–50% increase in cellular calcium concentrations. Of note, the effects of methylprednisolone were seen both in muscle cells from patients without muscle disease and in muscle cells from patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Because methylprednisolone increased calcium levels in myoblasts, but not in myotubes from normal muscle, it was speculated that the increase in calcium levels may have been secondary to glucocorticoid-mediated stimulation of myogenesis (74). In the present study, dexamethasone stimulated TG- and AVP-induced SOCE in both myoblasts and differentiated myotubes, suggesting that the dexamethasone-induced increase in SOCE did not reflect dexamethasone-regulated muscle cell differentiation, at least not under the present experimental conditions. It should be noted that in the study by Vandebrouck et al. (74), the influence of methylprednisolone on muscle cell calcium levels was determined but SOCE was not assessed.

Apparently conflicting results with regard to the effects of glucocorticoids on muscle cell calcium homeostasis were reported in a series of papers by Ruegg and coworkers (41, 51, 57). In those studies, treatment with methylprednisolone of C2C12 myotubes or of cultured muscle cells isolated from the hindlimbs of wild-type or dystrophin-deficient mutant mdx mice resulted in reduced calcium uptake and cellular concentrations of calcium. An even more pronounced inhibition of calcium uptake was observed after treatment with dexamethasone (57). Importantly, the effects of glucocorticoids on SOCE were not determined in the reports by Ruegg and coworkers (41, 51, 57). The reason(s) for the conflicting results is not apparent but may be related to species differences, human muscle cells being studied by Vandebrouck et al. (74) and mouse myocytes being used by Ruegg and coworkers (41, 51, 57).

In addition to muscle cells, the influence of glucocorticoids on calcium homeostasis has also been examined in other cell types, including thymocytes, mouse lymphoma cells, astrocytes, and human B lymphoblasts (6, 19, 38, 48, 66). In most of those studies, glucocorticoids increased calcium influx and cytosolic concentrations, and results were consistent with glucocorticoid-mediated changes in calcium stores and increased SOCE. Thus glucocorticoid-induced changes in calcium homeostasis, including increased SOCE, are probably not limited to skeletal muscle cells but may be important in other cell types as well.

Results in the present report, both from the initial experiments studying changes in calcium levels by the continual measurement of fura-2 fluorescence in myotubes on collagen-coated coverslips and from the experiments measuring SOCE, suggest that the dexamethasone treatment did not have an immediate effect on calcium homeostasis but required several hours to be noticeable. Similar observations were reported previously (38, 48). For example, when cultured mouse lymphoma cells were treated with dexamethasone, it took 3–4 h to deplete cellular calcium stores (38). This delay was interpreted as being consistent with a model in which glucocorticoid-induced calcium fluxes are the result of GR-mediated transcriptional activation of gene(s) involved in the regulation of calcium uptake and retention by the ER. This interpretation was supported by the results from experiments in which the effects of glucocorticoids on calcium uptake and concentrations were blocked by actinomycin D in the present and other studies (48). Results in other reports as well suggest that glucocorticoids regulate cellular calcium homeostasis through the classic GR-mediated genomic mechanism rather than through rapid, nongenomic mechanisms (19, 38, 48).

It is not known at present which GR-regulated gene(s) are involved in glucocorticoid-induced changes in calcium homeostasis. Although increased iPLA2 activity was involved in dexamethasone-induced SOCE activation in the present study, unchanged mRNA and protein levels of the phospholipase suggest that dexamethasone did not activate transcription of the iPLA2 gene. It is possible that a protein or proteins that regulate the activity of iPLA2, for example, CIF (67), or factors regulating the depletion of calcium from the SR were produced in response to dexamethasone. In addition, increased expression of store-operated calcium channels or factors that influence the activity of the channels, such as stromal interaction molecule (STIM) 1 and 2 (8, 42, 83), may be involved in dexamethasone-induced activation of SOCE. It will be important in future studies to determine the specific gene products that are involved in glucocorticoid-induced calcium entry in skeletal muscle cells.

Increased cellular calcium concentrations may have multiple consequences pertinent to muscle wasting. For example, it is an old observation that calcium can stimulate muscle protein breakdown (16, 34). This effect of calcium may reflect increased calpain (14, 77) and proteasome (50) activity. Most likely, other consequences of increased calcium levels are also involved in the regulation of muscle mass, such as activation of transcription factors and various nuclear cofactors that regulate gene transcription (5).

An important finding in the present study was that increased calcium entry and cytoplasmic calcium concentrations may be involved in glucocorticoid-induced muscle proteolysis. These observations are important in the context of previous reports in which muscle calcium uptake and concentrations were increased during sepsis (4, 15, 79) and after burn injury (64), conditions associated with increased muscle protein degradation (13, 71). Because other studies suggest that the increase in muscle proteolysis in these and other catabolic conditions is, at least in part, mediated by glucocorticoids (13, 22, 63, 71), it may be speculated that a glucocorticoid-mediated increase in SOCE is involved in stimulated muscle proteolysis in these conditions. If that is the case, it still remains to be determined which mechanism(s) accounts for the depletion (or reduction) of calcium stores allowing for activation of SOCE in muscle-wasting conditions. Previous studies suggest that sensitization of the ryanodine receptor (RyR)1 channel may participate in emptying of calcium stores and activation of SOCE in skeletal muscle (65). Interestingly, in a recent study in our laboratory (15), treatment of rats with the RyR1 inhibitor dantrolene prevented sepsis-induced increase in muscle calcium levels (and protein breakdown rates), suggesting that RyR1-mediated calcium store depletion, followed by activation of SOCE, may have been a mechanism of the increased muscle calcium levels noted in that study. An alternative mechanism for reducing SR calcium levels is inhibition of SERCA activity (58). In recent experiments in our laboratory (unpublished observations), SERCA2 protein levels were reduced in skeletal muscle of septic rats, providing support for a potential role of inhibited SERCA activity in SOCE during sepsis. The exact role of RyR1, SERCA, and other potential mechanisms that may account for depletion of calcium stores, increased SOCE, and protein breakdown in muscle wasting caused by glucocorticoids, sepsis, and other catabolic conditions remains to be determined.

GRANTS

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Grants DK-037908 (P.-O. Hasselgren), NR-008545 (P.-O. Hasselgren), GM-059179 (C. Hauser), and DK-069929 (D. Soybel).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Victoria Petkova for performing the real-time PCR assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ackermann EJ, Conde-Frieboes K, Dennis EA. Inhibition of macrophage Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 by bromoenol lactone and trifluoromethyl ketones. J Biol Chem 270: 445–450, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderton JM, Steinhardt RA. Calcium influx through calcium leak channels is responsible for the elevated levels of calcium-dependent proteolysis in dystrophic myotubes. J Biol Chem 275: 9452–9460, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basset O, Boittin FX, Dorchies OM, Chatton JY, van Breemen C, Ruegg UT. Involvement of 1,4,5-triphosphate in nicotinic calcium responses in dystrophic myotubes assessed by near-plasma membrane calcium measurement. J Biol Chem 279: 47092–47100, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson DW, Hasselgren PO, Hiyama DT, James JH, Li S, Rigel DF, Fischer JE. Effect of sepsis on calcium uptake and content in skeletal muscle and regulation in vitro by calcium of total and myofibrillar protein breakdown in control and septic muscle: results from a preliminary study. Surgery 106: 87–93, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Ca2+ signaling: dynamics, homeostasis, remodeling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 517–529, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bian X, Hughes FM, Huang Y, Cidlowski JA, Putney JW. Roles of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and intracellular Ca2+ stores in induction and suppression of apoptosis in S49 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C1241–C1249, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boittin FX, Petermann O, Hirn C, Mittand P, Dorchies OM, Roulet E, Ruegg UT. Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 enhances store-operated Ca2+ entry in dystrophic skeletal muscle fibers. J Cell Sci 119: 3733–3742, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS, Meyer T. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell 131: 1327–1339, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162: 156–159, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csukly K, Ascah A, Matas J, Gardiner PF, Fontaine E, Burelle Y. Muscle denervation promotes opening of the permeability transition pore and increases the expression of cyclophilin D. J Physiol 574: 319–327, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diederich S, Hanke B, Burkhardt P, Muller M, Schoneshofer M, Bahr V, Oelkers W. Metabolism of synthetic corticosteroids by 11beta-hydroxysteroid-dehydrogenases in man. Steroids 63: 271–277, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du J, Mitch WE, Wang X, Price SR. Glucocorticoids induce proteasome C3 subunit expression in L6 muscle cells by opposing the suppression of its transcription by NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem 275: 19661–19666, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang CH, James JH, Ogle C, Fischer JE, Hasselgren PO. Influence of burn injury on protein metabolism in different types of skeletal muscle and the role of glucocorticoids. J Am Coll Surg 180: 33–42, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fareed MU, Evenson AR, Wei W, Menconi M, Poylin V, Petkova V, Pignol B, Hasselgren PO. Treatment of rats with calpain inhibitors prevents sepsis-induced muscle proteolysis independent of atrogin-1 and MuRF1 expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1589–R1597, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer DR, Sun X, Williams AB, Gang G, Pritts TA, James JH, Molloy M, Fischer JE, Paul R, Hasselgren PO. Dantrolene reduces serum TNFalpha and corticosterone levels and muscle calcium, calpain gene expression, and protein breakdown in septic rats. Shock 15: 200–207, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furuno K, Goldberg AL. The activation of protein degradation in muscle by Ca2+ or muscle injury does not involve a lysosomal mechanism. Biochem J 237: 859–864, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gailly P. New aspects of calcium signaling in skeletal muscle cells: implications in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1600, 38–44, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbrecht MR, Schmidt TJ, Krozowski ZS, Snyder JM. 11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 and the regulation of surfactant protein A by dexamethasone metabolites. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E653–E660, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner JP, Zhang L. Glucocorticoid modulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in human B lymphoblasts. J Physiol 514: 385–396, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hantash BM, Thomas AP, Reeves JP. Regulation of the cardiac L-type calcium channel in L6 cells by arginine-vasopressin. Biochem J 400: 411–419, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasselgren PO. Glucocorticoids and muscle catabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2: 201–205, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasselgren PO, Chen IW, James JH, Sperling M, Fischer JE. Studies on the possible role of thyroid hormone in accelerated muscle protein breakdown during sepsis. Ann Surg 206: 18–24, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasselgren PO, Menconi MJ, Fareed MU, Yang H, Wei W, Evenson A. Novel aspects on the regulation of muscle wasting in sepsis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2156–2168, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi R, Wada H, Ito K, Adcock IM. Effects of glucocorticoids on gene transcription. Eur J Pharmacol 500: 51–62, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He LP, Hewavitharana T, Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Gill DL. A functional link between store-operated and TRPC channels revealed by the 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazol derivative, BTP2. J Biol Chem 280: 10997–11006, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hichami A, Joshi B, Simonin AM, Khan NA. Role of three isoforms of phospholipase A2 in capacitative calcium influx in human T-cells. Eur J Biochem 269: 5557–5563, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hobler SC, Williams A, Fischer D, Wang JJ, Sun X, Fischer JE, Monaco JJ, Hasselgren PO. Activity and expression of the 20S proteasome are increased in skeletal muscle during sepsis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 277: R434–R440, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong DH, Forsberg NE. Effects of dexamethasone on protein degradation and protease gene expression in rat L8 myotube cultures. Mol Cell Endocrinol 108: 199–209, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iannaccone ST. Current status of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Neurol 39: 879–893, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imbert N, Cognard C, Duport G, Guillou C, Raymond G. Abnormal calcium homeostasis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy myotubes contracting in vitro. Cell Calcium 18: 177–186, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Itagaki K, Kannan KB, Livingston DH, Deitch EA, Fekete Z, Hauser CJ. Store-operated calcium entry in human neutrophils reflects multiple contributions from independently regulated pathways. J Immunol 168: 4063–4069, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenkins CM, Han X, Mancuso DJ, Gross RW. Identification of calcium-independent iPLA2 (iPLA2) β, and not iPLA2 γ, as the mediator of arginine vasopressin-induced arachidonic acid release in A-10 smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 277: 32807–32814, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kameyama T, Etlinger JD. Calcium-dependent regulation of protein synthesis and degradation in muscle. Nature 279: 344–346, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kmonickova E, Melkusova P, Harmatha J, Vocak K, Farghali H, Zidek Z. Inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase thapsigargin stimulates production of nitric oxide and secretion of interferon-gamma. Eur J Pharmacol 588: 85–92, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krozowski Z, Li KX, Koyama K, Smith RE, Obeyesekere VR, Stein-Oakley A, Sasano H, Coulter C, Cole T, Sheppard KE. The type I and type II 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzymes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 69: 391–401, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurebayashi N, Ogawa Y. Depletion of Ca2+ in the sarcoplasmic reticulum stimulates Ca2+ entry into mouse skeletal muscle fibers. J Physiol 533: 185–199, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lam M, Dubyak G, Distelhorst CW. Effect of glucocorticosteroid treatment on intracellular calcium homeostasis in mouse lymphoma cells. Mol Endocrinol 7: 686–693, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latres E, Amini AR, Amini AA, Griffiths J, Martin FJ, Wei Y, Lin HC, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) inversely regulates atrophy-induced genes via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 2737–2744, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Launikonis BS, Rios E. Store-operated Ca2+ entry during intracellular Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Physiol 583: 81–97, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leijendekker WJ, Passaquin AC, Metzinger L, Ruegg UT. Regulation of cytosolic calcium in skeletal muscle cells of the mdx stress. Br J Pharmacol 118: 611–616, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liou J, Fivaz M, Inone T, Meyer T. Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 9301–9306, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Losel R, Wehling M. Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 46–56, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowenberg M, Stahn C, Hummes DW, Buttgereit F. Novel insights into mechanisms of glucocorticoid action and the development of new glucocorticoid ligands. Steroids 73: 1025–1029, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma J, Pan Z. Junctional membrane structure and store operated calcium entry in muscle cells. Front Biosci 8: d242–d255, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez J, Moreno JJ. Role of Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 and cytochrome P-450 in store-operated calcium entry in 3T6 fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol 70: 733–739, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarter FD, Nierman SR, James JH, Wang L, King JK, Friend LA, Fischer JE. Role of skeletal muscle Na+-K+ ATPase activity in increased lactate production in sub-acute sepsis. Life Sci 70: 1875–1888, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McConkey DJ, Nicotera P, Hartzell P, Bellomo G, Wyllie AH, Orrenius S. Glucocorticoids activate a suicide process in thymocytes through an elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Arch Biochem Biophys 269: 365–370, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Menconi M, Gonnella P, Petkova P, Lecker S, Hasselgren PO. Dexamethasone and corticosterone induce similar, but not identical, muscle wasting responses in cultured L6 and C2C12 myotubes. J Cell Biochem 105: 353–364, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menconi MJ, Wei W, Yang H, Wray CJ, Hasselgren PO. Treatment of cultured myotubes with the calcium ionophore A23187 increases proteasome activity via a CaMK II-caspase-calpain-dependent mechanism. Surgery 136: 135–142, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Metzinger L, Passaquin AC, Leijendekker WJ, Poindron P, Ruegg UT. Modulation by prednisolone of calcium handling in skeletal muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 116: 2811–2816, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Mechanisms of muscle wasting. N Engl J Med 335: 1897–1905, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moresi V, Garcia-Alvarez G, Pristera A, Rizzuto E, Albertini MC, Rocchi M, Marazzi G, Sassoon D, Adamo S, Coletti D. Modulation of caspase activity regulates skeletal muscle regeneration and function in response to vasopressin and tumor necrosis factor. PLoS ONE 4: e5570, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicotera TM, Schuster DP, Bourhim M, Chada K, Klaich G, Corral DA. Regulation of PSA secretion and survival signaling by calcium-independent phospholipase A2β in prostate cancer cells. Prostate 69: 1270–1280, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ozdemir S, Bito V, Holemans P, Vinet L, Mercadier JJ, Varro A, Sipido KR. Pharmacological inhibition of Na/Ca exchange results in increased cellular Ca2+ load attributable to the predominance of forward mode block. Circ Res 102: 1398–1405, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parekh AB, Putney JW. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85: 757–810, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Passaquin AC, Lhote P, Ruegg UT. Calcium influx inhibition by steroids and analogs in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 124: 1751–1759, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Periasamy M, Kalyanasundaram A. SERCA pump isoforms: their role in calcium transport and disease. Muscle Nerve 35: 430–442, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Philibert D. RU 38486: an original multifaceted antihormone in vivo. In: Adrenal Steroid Antagonism, edited by Agarwal MK. Hawthorne, NY: de Gruyter, 1984, p. 77–100 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Randriamampita C, Tsien RY. Emptying of intracellular Ca2+ stores releases a novel small messenger that stimulates Ca2+ influx. Nature 364: 809–814, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rzigalinski BA, Willoughby KA, Hoffman SW, Falck JR, Ellis EF. Calcium influx factor, further evidence it is a 5,6-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid. J Biol Chem 247: 175–182, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sacheck JM, Ohtsuka A, McLary SC, Goldberg AL. IGF-I stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E591–E601, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 117: 399–412, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sayeed MM. Signaling mechanisms of altered cellular responses in trauma, burn, and sepsis: role of Ca2+. Arch Surg 135: 1432–1442, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shevchenko S, Feng W, Varsanyi M, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Identification, characterization and partial purification of a thiol-protease which cleaves specifically the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel. J Membr Biol 161: 33–43, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simard M, Couldwell WT, Zhang W, Song H, Liu S, Cotrina ML, Goldman S, Nedergaard M. Glucocorticoids—potent modulators of astrocytic calcium signaling. Glia 28: 1–12, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smani T, Zakharov SI, Csutora P, Leno E, Trepakova EC, Bolotina VM. A novel mechanism for the store-operated calcium influx pathway. Nat Cell Biol 6: 113–120, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smani T, Zackharov SI, Leno E, Csutora P, Trepakova ES, Bolotina VM. Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 is a novel determinant of store-operated Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem 278: 11909–11915, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stahn C, Buttgereit F. Genomic and nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 4: 525–533, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suzuki S, Koyama K, Darnel A, Ishibashi H, Kobayashi S, Kubo H, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Krozowski ZS. Dexamethasone upregulates 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in BEAS-2B cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 1244–1249, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tiao G, Fagan J, Roegner V, Lieberman M, Wang JJ, Fischer JE, Hasselgren PO. Energy-ubiquitin-dependent muscle proteolysis during sepsis in rats is regulated by glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest 97: 339–348, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tiao G, Fagan JM, Samuels N, James JH, Hudson K, Lieberman M, Fischer JE, Hasselgren PO. Sepsis stimulates nonlysosomal, energy-dependent proteolysis and increases ubiquitin mRNA levels in rat skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest 94: 2255–2264, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vandebrouck A, Ducret T, Basset O, Sebille S, Raymond G, Ruegg U, Gailly P, Cognard C, Constantin B. Regulation of store-operated calcium entries and mitochondrial uptake by minidystrophin expression in cultured myotubes. FASEB J 20: 136–138, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vandebrouck C, Imbert N, Duport G, Cognard C, Raymond G. The effect of methylprednisolone on intracellular calcium of normal and dystrophic human skeletal muscle cells. Neurosci Lett 269: 110–114, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh BM, Naik HB, Dubach JM, Beshire M, Wieland AM, Soybel DI. Thiol-oxidant monochloramine mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ in parietal cells of rabbit gastric glands. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1687–C1697, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang L, Luo GJ, Wang JJ, Hasselgren PO. Dexamethasone stimulates proteasome- and calcium-dependent proteolysis in cultured L6 myotubes. Shock 10: 298–306, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wei W, Fareed MU, Evenson A, Menconi M, Yang H, Petkova V, Hasselgren PO. Sepsis stimulates calpain activity in skeletal muscle by decreasing calpastatin activity but does not activate caspase-3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R580–R590, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winstead MV, Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2: structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1488: 28–39, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wray CJ, Sun X, Gang G, Hasselgren PO. Dantrolene downregulates the gene expression and activity of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in septic skeletal muscle. J Surg Res 104: 82–87, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yaffe D. Retention of differentiation potentialities during prolonged cultivation of myogenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 61: 477–483, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang H, Wei W, Menconi M, Hasselgren PO. Dexamethasone-induced protein degradation in cultured myotubes is p300/HAT dependent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R337–R344, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zablocki K, Wasniewska M, Duszynski J. Participation of phospholipase A2 isoforms in the control of calcium influx into electrically non-excitable cells. Acta Biochim Pol 47: 591–599, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang SL, Yu Y, Roos J, Kozak JA, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. STIM 1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 437: 902–905, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zitt C, Strauss B, Schwarz EC, Spaeth N, Rast G, Hatzelmann A, Hoth M. Potent inhibition of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels and T-lymphocyte activation by the pyrazole derivative BTP2. J Biol Chem 279: 12427–12437, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]