Abstract

We recently demonstrated that thapsigargin-induced passive store depletion activates Ca2+ entry in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) through stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1)/Orai1, independently of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels. However, under physiological stimulations, despite the ubiquitous depletion of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive stores, many VSMC PLC-coupled agonists (e.g., vasopressin and endothelin) activate various store-independent Ca2+ entry channels. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is an important VSMC promigratory agonist with an established role in vascular disease. Nevertheless, the molecular identity of the Ca2+ channels activated by PDGF in VSMC remains unknown. Here we show that inhibitors of store-operated Ca2+ entry (Gd3+ and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate at concentrations as low as 5 μM) prevent PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry in cultured rat aortic VSMC. Protein knockdown of STIM1, Orai1, and PDGF receptor-β (PDGFRβ) impaired PDGF-mediated Ca2+ influx, whereas Orai2, Orai3, TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6 knockdown had no effect. Scratch wound assay showed that knockdown of STIM1, Orai1, or PDGFRβ inhibited PDGF-mediated VSMC migration, but knockdown of STIM2, Orai2, and Orai3 was without effect. STIM1, Orai1, and PDGFRβ mRNA levels were upregulated in vivo in VSMC from balloon-injured rat carotid arteries compared with noninjured control vessels. Protein levels of STIM1 and Orai1 were also upregulated in medial and neointimal VSMC from injured carotid arteries compared with noninjured vessels, as assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. These results establish that STIM1 and Orai1 are important components for PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry and migration in VSMC and are upregulated in vivo during vascular injury and provide insights linking PDGF to STIM1/Orai1 during neointima formation.

Keywords: store-operated calcium channels, transient receptor potential canonical channels, platelet-derived growth factor, smooth muscle dedifferentiation, neointima formation

vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) are one of the major cell types in blood vessels that play a central role in controlling the vascular tone and maintaining the integrity of the vessel wall (19, 49). Stimulation of VSMC membrane receptors by vasoactive compounds (e.g., vasopressin and angiotensin II) and growth factors [e.g., platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and fibroblast growth factor] that typically couple to isoforms of PLC induces phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate breakdown into two second messengers: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 causes Ca2+ release through IP3 receptors from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (9). Since the amount of Ca2+ in the internal stores is finite, Ca2+ entry across plasma membrane channels is typically activated to replenish the empty stores and maintain a sustained increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ necessary for signaling downstream to the nucleus. One of the major routes for Ca2+ entry into cells is through store-operated Ca2+ (SOC) entry (SOCE) channels, which are activated by internal Ca2+ store depletion (36). Depletion of internal Ca2+ stores induces the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/SR-resident Ca2+ store sensor stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) to translocate to areas near the plasma membrane to signal the activation of SOC channels encoded by Orai1 proteins (13, 14, 17, 35). However, in addition to Ca2+-selective Orai1 (33, 34), diverse SOC conductances encoded by transient receptor potential (TRP) canonical (TRPC) proteins have been described in many VSMC types (2, 3, 42). We and others recently demonstrated the upregulation of STIM1/Orai1 proteins in vitro in synthetic cultured VSMC compared with quiescent contractile freshly isolated VSMC (8, 34). We also showed that passive store depletion by thapsigargin activates Ca2+ entry in VSMC through STIM1/Orai1, independently of Orai2, Orai3, and TRPC channels (34), and that store depletion-activated Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current-like currents are present in cultured synthetic migratory VSMC encoded by STIM1/Orai1 (34). Baryshnikov and coworkers (6) subsequently confirmed that SOCE is mediated by Orai1, independently of Orai2 and Orai3, and provided evidence for a functional association between Orai1, the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, and the plasma membrane-associated Ca2+-ATPase pump in proliferating smooth muscle cells. However, under physiological agonist, i.e., PDGF, stimulation, the exact Ca2+ entry route activated remains uncertain. Despite concomitant depletion of IP3-sensitive stores, ligation of many PLC-coupled receptors activates, instead, distinct Ca2+ entry channels that do not depend on the state of filling of the internal stores (11, 39). For instance, the store-independent arachidonic acid-activated Ca2+ entry pathway mediated by arachidonic acid-activated channels is activated in response to PLC-coupled receptor stimulation under certain agonist conditions (39, 40). Recently, arachidonic acid-activated channels were shown to depend on plasma membrane STIM1 and to be contributed by Orai1 and Orai3 proteins (27, 28). Furthermore, stimulation of α1-adrenergic receptors activates store-independent Ca2+ entry through the diacylglycerol-activated TRPC6 channel (22). Heteromultimeric TRPC6 and TRPC7 channels were shown to contribute to vasopressin-activated Ca2+ entry in A7r5 smooth muscle cells (26), and increased Ca2+ entry induced by endothelin-1, another PLC-coupled receptor vasoactive agonist, was attenuated by TRPC3 knockdown (50).

Expression of PDGF can occur in all resident cells of the artery and in inflammatory cells that infiltrate the artery during disease (37). PDGF and its receptors are expressed at low or undetectable levels in normal vessels, but their expression is increased during vascular injury and atherosclerosis (37). It is now clearly established that PDGF plays a prominent role in migration of VSMC into the neointima following acute vessel injury or in the presence of atherosclerotic lesions (37). PDGF mediates its effects through binding to its receptor with subsequent Ca2+ mobilization. However, the molecular identity of the Ca2+ influx channels activated by PDGF, in general, and in VSMC, in particular, remains unknown.

In this study, we investigated the contribution of several Ca2+ channel candidates, known to be activated downstream of PLC isoforms, to the molecular composition of PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry channels in VSMC. We employed protein knockdown using silencing RNA (siRNA) against PDGF receptor-β (PDGFRβ), the Ca2+ sensor STIM1, all three Orai isoforms, and the three TRPC isoforms expressed in primary VSMC (TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6). We show that PDGF activates Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane through the STIM1-Orai1 pathway, independently of TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6 and Orai2 and Orai3 proteins. We also show that STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown inhibits VSMC migration in response to PDGF in vitro and that STIM1 and Orai1 are upregulated in vivo in neointimal VSMC during vascular injury.

METHODS

Reagents.

Gd3+ was purchased from Acros Oragnic; recombinant rat PDGF-BB from R & D Biosystems; and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) from Calbiochem. All siRNA sequences were obtained from Dharmacon and, along with specific primers for rat STIM, Orai, and TRPC, are described elsewhere (34). The following primers were used: CGCATGGCCCAACCTGCTCA (forward) and TCGGAGGCTGTGGAGACCCG (reverse) for rat PDGFRβ and GUAGAAAUCCUUGGGUAUA (siRNA1) and ACAUCAAAUACGCGGACAU (siRNA2) for the siRNA against rat PDGFRβ. Anti-STIM1 was purchased from BD Biosciences, anti-β-actin NH2-terminal domain from Sigma, and anti-Orai1 (extracellular; catalog no. ACC-060) from Alomone. Western blot and immunofluorescence data were generated using the anti-Orai1 against the extracellular domain (Alomone), and similar results were obtained using anti-Orai1 antibodies from Sigma (catalog no. O8264) and ProSci (catalog no. 4041). All other chemical products were obtained from Fisher Scientific unless specified otherwise.

VSMC dispersion and culture.

Male rats were euthanized by suffocation in a CO2 chamber. Aortas were dissected out into ice-cold physiological saline solution. Fat tissues and endothelium were removed. The artery was cut into small pieces and digested with a papain solution for 20 min at 37°C and then with a mixture of collagenase II and collagenase for 15 min at 37°C. The digestion solution was removed, and the cells were washed and gently liberated with a fire-polished glass pipette and transferred to culture plates. Isolated VSMC undergo phenotypic modulation in culture that is complete within 30 h (18). Isolated VSMC were maintained in culture (45% DMEM-45% Ham's F-12–10% FBS supplemented with l-glutamine) at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity, passaged (synthetic), and used within one to six passages in all experiments.

RT-PCR and real-time PCR.

Detailed protocol and sequences of specific primers are described elsewhere (34). Expression of TRPC, STIM, or Orai was compared with expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH and measured using the comparative threshold cycle method, as previously described (1, 34).

Cell transfections.

Transfections in VSMC were carried out using Nucleofector II (Amaxa) according to the manufacturer's instructions. As a marker of cell transfection, 0.5 μg of green fluorescent protein was cotransfected with siRNA for identification of successfully transfected cells during experiments. As a control, we used a scrambled nontargeting sequence, as reported previously (34). For Ca2+ imaging experiments, cells were transfected with 10 μg of the siRNA of choice per 1 × 106 cells, seeded to round glass coverslips (for imaging) or plates (for various assays), and used 72 h after transfection.

Ca2+ measurements.

Ca2+ was measured as described previously (1, 45, 47). Briefly, coverslips with attached cells were mounted in a Teflon chamber and incubated at 37°C for 45 min in culture medium (DMEM with 10% FBS) containing 4 μM fura 2-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were then washed and bathed in HEPES-buffered saline solution (in mM: 140 NaCl, 1.13 MgCl2, 4.7 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose, and 10 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH) for ≥10 min before Ca2+ was measured. For Ca2+ measurements, fluorescence images of several cells were recorded and analyzed with a digital fluorescence imaging system (InCyt Im2, Intracellular Imaging, Cincinnati, OH). Fura 2 fluorescence at an emission wavelength of 510 nm was induced by excitation of fura 2 alternately at 340 and 380 nm. The ratio of fluorescence at 340 nm to that at 380 nm was obtained on a pixel-by-pixel basis. All experiments were conducted at room temperature.

Western blots.

Cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 0.2 mM EDTA], and 20–50 μg of proteins in denaturing conditions were subjected to SDS-PAGE (7.5%) and then electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After the blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (NFDM) dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TTBS) for 2 h at room temperature, they were washed three times with TTBS for 5 min each and probed overnight at 4°C with specific primary antibodies [anti-STIM1 (1:250 dilution), anti-Orai1 (Alomone; 1:1,000 dilution), and β-actin NH2-terminal (NT) domain (1:2,000 dilution)] in TTBS containing 2% NFDM. On the next day, membranes were washed (3 times for 5 min each) with TTBS and incubated for 45 min at room temperature with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (1:10,000 dilution; Jackson) for STIM1 and actin or anti-rabbit IgG for Orai1 (1:20,000 dilution; Jackson) in TTBS containing 2% NFDM. Detection was performed using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham).

Migration assays.

VSMC were transfected with scrambled control or target siRNA, seeded, and allowed to form a monolayer for 48 h. The dish was scraped with the tip of a 100-μl pipette, and the resulting wound was washed with PBS. Culture medium containing 0.4% FBS with or without 100 ng/ml PDGF was added to the cells, which were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. VSMC showed very little or no migratory response in the absence of PDGF. At different times, bright-field images were captured at ×10 magnification (Leica DM IRB microscope) and analyzed (Adobe Photoshop CS3), and the total number of pixels in empty spaces inside the wound were counted and normalized to the control (scrambled siRNA) to gauge changes associated with knockdown of specific proteins. Data are represented as percentage of migration relative to the scrambled siRNA control.

Balloon injury of rat carotid arteries.

The use of rats for these experiments has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Albany Medical College Animal Resource Facility, which is licensed by the US Department of Agriculture and the Division of Laboratories and Research of the New York State Department of Public Health and is accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (350–400 g body wt; Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) were anesthetized with xylazine (5 mg/kg) and ketamine (70 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection, and balloon angioplasty was carried out essentially as previously described (20). Briefly, an embolectomy was performed as follows: a 2-F Fogarty balloon was inserted through a small arteriotomy in the external carotid artery and passed into the common carotid artery. After balloon inflation at 2 atm pressure, the catheter was partially withdrawn and reinserted three times. After recovery from operation and anesthesia, animals received a postoperative dose of the analgesic buprenorphine (Buprenex; 0.02 mg/kg sc). Sham-operated animals were subjected to a similar procedure but without balloon insertion.

Immunofluorescence.

Rats were euthanized by asphyxiation with CO2, and injured or noninjured carotid arteries were harvested and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and frozen by submersion in liquid nitrogen. Tissue sections (7 μm) were cut using a cryostat (Leica CM3050), mounted onto glass slides, and stored at −80°C. The carotid sections were fixed with precooled acetone for 10 min at 4°C and rinsed with 1× PBS. The sections were incubated in a PBS washing buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, in blocking buffer (1× PBS, 5% goat serum, 0.5% fish gelatin, and 0.1% Triton X-100) for 30 min and then with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. A mouse monoclonal anti-STIM1 primary antibody was diluted 1:25 (BD Biosciences), or three rabbit polyclonal anti-Orai1 antibodies {anti-Orai1 extracellular [catalog no. ACC-060(6), Alomone], Orai1 NT domain [catalog no. 4041(34), ProSci], and anti-Orai1 (catalog no. O8264, Sigma)}, used independently, were diluted 1:25, 1:10, and 1:25, respectively, in blocking buffer. All three Orai1 antibodies showed similar results: robust upregulation of Orai1 in injured vessel sections. The sections were rinsed with washing buffer and then incubated with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. For STIM1 staining, an FITC-coupled anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) was diluted 1:300 in blocking buffer. For Orai1 staining, an FITC-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) was diluted 1:300 in blocking buffer. Control sections were stained with secondary antibodies alone. Finally, the sections were mounted with a mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The sections were later visualized using a confocal microscope (LSM 510 META). Images were collected using a ×63 oil immersion lens and a zoom setting of 0.7 (low magnification) or 2 (high magnification). LSM software was used to drive the hardware and image acquisition. For images collected at low magnification, intensity levels can be visualized without modification; for images collected at high magnification, ImageJ and Photoshop were used to provide a higher level of contrast for better visualization of protein subcellular distribution. Vertical sections were collected at high magnification at 0.5-μm intervals, with pinhole settings at 1 Airy unit. ImageJ Volume Viewer plug-in was used to generate a vertical cross-sectional image using trilinear interpolation.

For immunofluorescence in cultured synthetic VSMC, cells were transfected with nontargeting siRNA or Orai1 siRNA (see above) and allowed to grow for 72 h on coverslips coated with collagen. At 4°C, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with paraformaldehyde. Cells were then permeabilized for 5 min with PBS-0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.5% fish gelatin) for 30 min. The cells were allowed to incubate overnight in anti-Orai1 primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer at 1:25 (Alomone) at 4°C. The cells were rinsed and then treated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody diluted in blocking buffer at 1:300 for 1 h. The coverslips were mounted in mounting medium containing DAPI and imaged using a wide-field microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1) at low (×40) magnification. Images show intensity levels without modification. Nonpermeabilized cells were treated for immunofluorescence using the same protocol without Triton X-100. After treatment with secondary antibody, the cells were allowed to incubate in wheat germ agglutinin-Alexa Fluor 594 at 4°C for 10 min at 5 μg/ml. The coverslips were mounted with a mounting medium containing DAPI and imaged using a confocal microscope (LSM 510 META) under high magnification and processed for visualization as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as the number of cells from several transfections (means ± SE). Each condition reflects results from several coverslips originating from at least two independent transfections. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA was carried out using Origin software. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Pharmacological characterization of PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry.

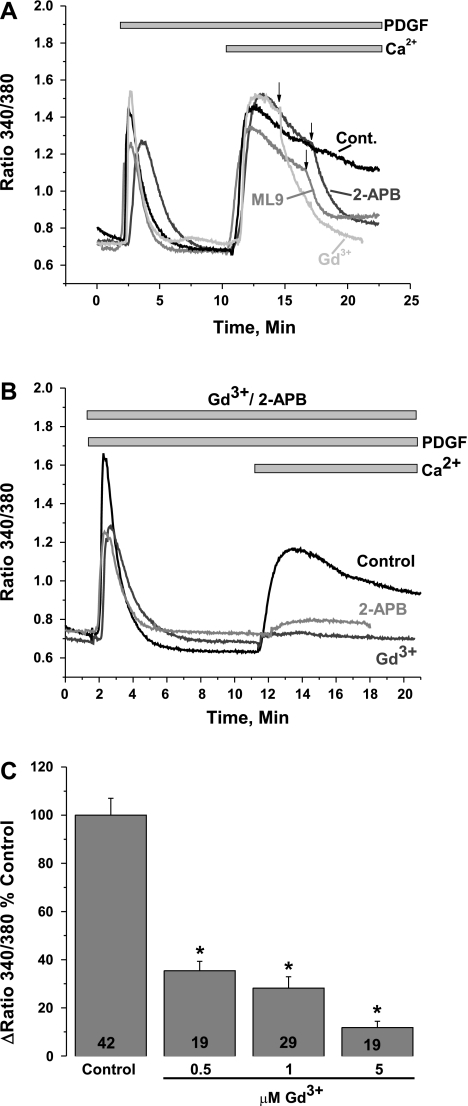

We recently showed that SOCE in human umbilical vein and human pulmonary artery endothelial cells and rat aortic VSMC is mediated by STIM1 and Orai1 independently of other Orai isoforms and TRPC proteins (1, 34). To test whether PDGF mediates Ca2+ entry in VSMC via store-dependent or store-independent channels, we used pharmacological inhibitors of SOCE and found that PDGF activates a Ca2+ entry pathway that displays classical SOCE features similar to those observed in nonexcitable cells, such as HEK-293 and rat basophilic leukemia cells. In primary cultured VSMC (synthetic), PDGF-evoked Ca2+ entry was essentially blocked with 5 μM Gd3+ and 30 μM 2-APB and, as recently demonstrated in HEK-293 cells (41), by 50 μM ML-9 (Fig. 1A), suggesting that STIM1 and Orai1 might be the molecular players in the PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry pathway in VSMC. We showed recently that SOCE in primary cultured VSMC displays a unique feature, i.e., concentrations of 2-APB as low as 5 μM are inhibitory (34). In additional experiments in cells incubated with Gd3+ (5 μM) or 2-APB (5 μM) before restoration of extracellular Ca2+, PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry was also sensitive to these concentrations of Gd3+ and 2-APB in a manner that is reminiscent of thapsigargin-activated SOCE in VSMC (34) (Fig. 1B). Results similar to those described in Fig. 1, A and B, were obtained from experiments with the VSMC cell line A7r5 (data not shown). Dose-response analysis of Gd3+ inhibition showed that Gd3+ concentrations as low as 0.5 μM substantially inhibited PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry (64.64 ± 3.98% inhibition, n = 19), whereas 5 μM Gd3+ essentially inhibited PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry (88.18 ± 2.61% inhibition, n = 19; Fig. 1C) in a manner reminiscent of that seen with thapsigargin-activated SOCE in HEK-293 cells (44).

Fig. 1.

A: in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF, 50 ng/ml) activates Ca2+ release from internal stores in primary cultured vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). Upon Ca2+ restoration to the extracellular milieu (2 mM), PDGF activates a Ca2+ entry pathway (cont, average of results from 18 cells) that is sensitive to 5 μM Gd3+ (n = 8), 30 μM 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB, n = 29), and 50 μM ML-9 (n = 18). Arrows indicate addition of drugs. Values are expressed as ratio of fluorescence at 340 nm to fluorescence at 380 nm. B: preincubation with 5 μM Gd3+ (n = 10) or 5 μM 2-APB (n = 18) essentially abrogated PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry; n = 15 for control. C: dose-response inhibition of PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry by Gd3+. Note substantial inhibition of Ca2+ entry at 0.5 μM Gd3+. Numbers within bars represent total number of cells. All Ca2+ imaging traces show average data from several cells analyzed simultaneously. Data are representative of 3–4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

STIM1 and Orai1 mediate PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry in VSMC.

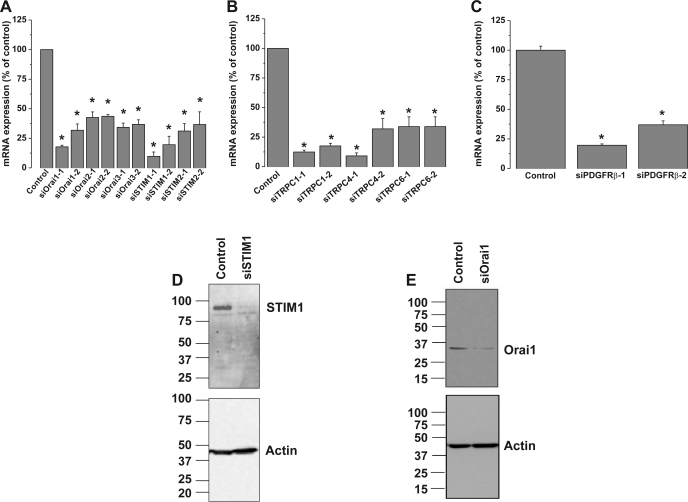

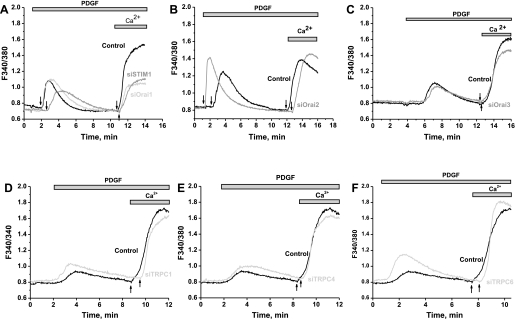

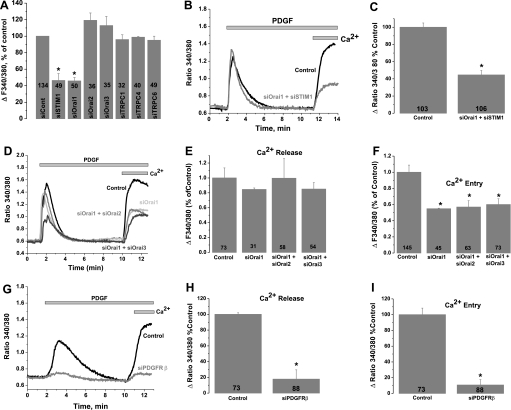

To determine the molecular identity of the plasma membrane Ca2+ channels activated by PDGF in primary cultured VSMC, we used siRNA against STIM1, Orai, and TRPC isoforms. Knockdown of STIM1, Orai, or TRPC isoforms in VSMC was achieved with two different siRNA sequences, used individually (see Ref. 34 for siRNA sequences). As measured by quantitative RT-PCR, siRNA sequences induced a marked decrease in their target mRNA levels 72 h after transfection (Fig. 2, A and B): by 82.14 ± 1.34% for siOrai1-1, 57.38 ± 4.68% for siOrai2-1, 65.67 ± 3.55% for siOrai3-1, 90.18 ± 3.57% for siSTIM1-1, 68.79 ± 6.23% for siSTIM2-1, 87.6 ± 1.6% for siTRPC1-1, 90.82 ± 2.48% for siTRPC4-1, and 66.1 ± 8.24% for siTRPC6-1 (n = 6). As assessed by Western blotting and reported previously (34), extensive characterization of the same siRNA in VSMC by our group showed that they induce a decrease in protein levels of their respective targets: by 74.7 ± 7.5% for STIM1-1, 58.3 ± 7.0% for Orai1-1, 58.8 ± 6.4% for Orai3-1, 61.8 ± 7.7% for TRPC1-1, 66.2 ± 12.1% for TRPC4-1, and 85.4 ± 5.8% for TRPC6-1 (n = 3). Representative Western blot analysis of STIM1 and Orai1 from cells transfected with scrambled control siRNA, siRNA against STIM1, or siRNA against Orai1 are shown in Fig. 2, D and E. Interestingly, downregulation of STIM1 or Orai1 using siRNA significantly suppressed PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry in primary cultured VSMC, whereas neither Orai2, Orai3, TRPC1, TRPC4, nor TRPC6 knockdown affected the amplitude of PDGF-induced Ca2+ entry in primary cultured VSMC (Fig. 3). Representative traces in Fig. 3 show an average of several VSMC originating from single coverslips 72 h after transfection with control scrambled siRNA or target siRNA and assayed on the same day. Knockdown of individual STIM, Orai, or TRPC isoforms in VSMC had no significant effect on SR Ca2+ release (data not shown). Figure 4A shows results from statistical analysis of Ca2+ entry measured using fura 2 imaging after knockdown of different proteins in several individual cells obtained from different coverslips from at least three independent transfections. The inhibition of Ca2+ entry compared with control was 53.58 ± 8.36% for siSTIM1 (n = 49) and 54.17 ± 4.16% (n = 50) for siOrai1, with no significant inhibition detected on knockdown of other proteins (Fig. 4A). Results are representative of two independent siRNA sequences per target gene and are normalized to control cells transfected with a scrambled siRNA (for sequence see Ref. 34). Simultaneous knockdown of STIM1 and Orai1 had an effect (55.43 ± 5.08% inhibition, n = 106) similar to knockdown of STIM1 or Orai1 alone, strongly arguing that both proteins are involved in the same pathway. Figure 4B shows a representative trace with average cells from the same coverslip, and Fig. 4C shows results from statistical analysis of several cells from three independent experiments. Given the incomplete knockdown of Orai2 and Orai3, the contribution of these proteins to SOCE in VSMC might be smaller. In a separate set of experiments, we compared double knockdown of Orai1 + Orai2 or Orai1 + Orai3 with single knockdown of Orai1. Figure 4D shows that the extent of SOCE inhibition is similar whether Orai1 is knocked down alone or in combination with Orai2 and Orai3. This lack of additivity suggests that Orai2 and Orai3 do not contribute significantly to SOCE in VSMC. However, we cannot rule out completely a small contribution from Orai2 and/or Orai3 to SOCE in VSMC. Figure 4, E and F, shows results from statistical analysis of three to four independent experiments where Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry were measured in cells transfected with control siRNA and siRNA against Orai isoforms.

Fig. 2.

A–C: quantitative RT-PCR assessment of mRNA levels of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM) and Orai, transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) isoforms, and PDGF receptor-β (PDGFRβ, C) after knockdown by transfection of 2 specific silent RNA (siRNA) sequences used independently or a scrambled siRNA sequence used as a control. After 72 h, mRNA was isolated from cells and reverse transcribed, and quantitative PCR was performed using specific primers. Sequences for siRNA and primers for STIM, TRPC, and Orai are provided elsewhere (34); sequences for primers and siRNA against PDGFRβ are provided in methods. Data are representative of 3 independent transfections performed in triplicates. *P < 0.05. D and E: Western blots showing STIM1 and Orai1 protein knockdown after siRNA transfection as previously reported (34). Data are representative of 4 independent experiments.

Fig. 3.

Representative traces showing average of PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry from several cells on single coverslips from scrambled control- or targeted siRNA-transfected VSMC on the same day. Results obtained with targeted siRNA against STIM1 and Orai1 (A), Orai2 (B), Orai3 (C), TRPC1 (D), TRPC4 (E), and TRPC6 (F) are shown. PDGF was used at 50 ng/ml for siOrai2 and at 25 ng/ml for all other recordings. Data are representative of 3–6 independent experiments per targeted siRNA. PDGF was first added in the absence of extracellular Ca2+; arrows show exact times of Ca2+ restoration to the extracellular milieu for each trace.

Fig. 4.

A: PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry after VSMC transfection with scrambled or targeted siRNA (against STIM1, Orai1, Orai2, Orai3, TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6) was measured using fura 2, and extent of Ca2+ entry was analyzed in several cells originating from several independent experiments and is represented as the difference between the fura 2 signal before and after Ca2+ (2 mM) restoration. Results are averages of cells from 3–6 independent experiments per condition. Numbers within bars represent total number of cells for each condition. B: representative traces depicting effect of STIM1 and Orai1 simultaneous silencing on PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry (n = 15). Condition with control scrambled siRNA-transfected cells (n = 22) is also shown. C: extent of Ca2+ entry in many scrambled control- and siOrai1 + siSTIM1-transfected cells. Results are averages 3 independent experiments; numbers within bars represent total number of cells. D: representative traces depicting effect of Orai1 (n = 15), siOrai1 + siOrai2 (n = 18), and siOrai1 + siOrai3 (n = 14) knockdown on PDGF-mediated Ca2+ entry compared with control scrambled siRNA-transfected cells (n = 20). E and F: Ca2+ release and entry in scrambled control-, siOrai1-, siOrai1 + siOrai2-, and siOrai1 + siOrai3-transfected cells. Results are averages from 3–4 independent experiments; numbers within bars represent total number of cells. G: representative traces depicting effect of PDGFRβ knockdown on PDGF-mediated Ca2+ release and entry (n = 16); control trace represents an average of 25 scrambled siRNA-transfected cells. H and I: Ca2+ release and entry in scrambled control- and PDGFRβ-transfected cells. Results are averages from 4 independent experiments; numbers within bars represent total number of cells. In all experiments, PDGF was used at a concentration of 50 ng/ml. *P < 0.05 vs. control for A, C, F, H, and I.

Protein knockdown of the PDGFRβ using two independent siRNA caused a substantial decrease in Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry in response to PDGF. Figure 4G shows representative traces from individual coverslips, and Fig. 4, H and I, shows results from statistical analysis of Ca2+ release (82.24 ± 11.8% inhibition, n = 88) and Ca2+ entry (89.29% ± 6.87 inhibition, n = 88), respectively, from four independent experiments. The ability of siRNAs against the PDGFRβ to induce a substantial decrease in PDGFRβ mRNA was determined by quantitative PCR (Fig. 2C): 80.04 ± 1.12% decrease for siPDGFRβ1 and 63.02% ± 3.3% decrease for siPDGFRβ2.

STIM1, Orai1, and PDGFRβ are important for PDGF-induced VSMC migration.

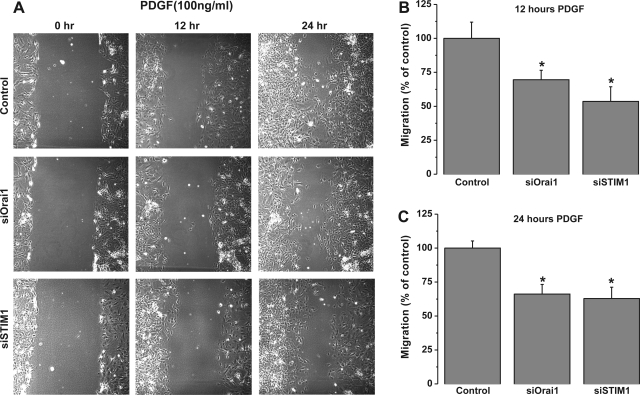

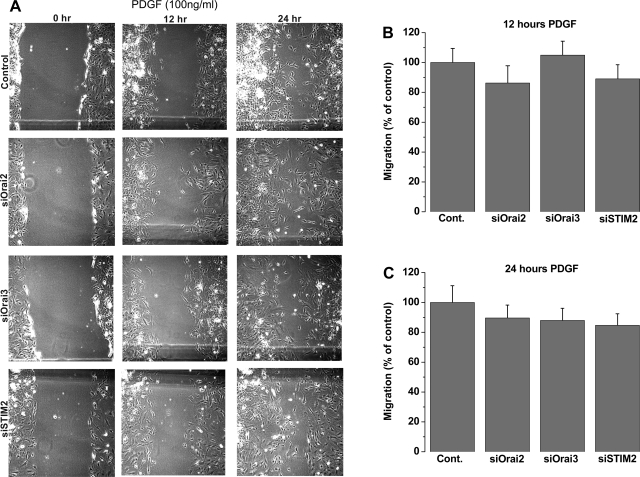

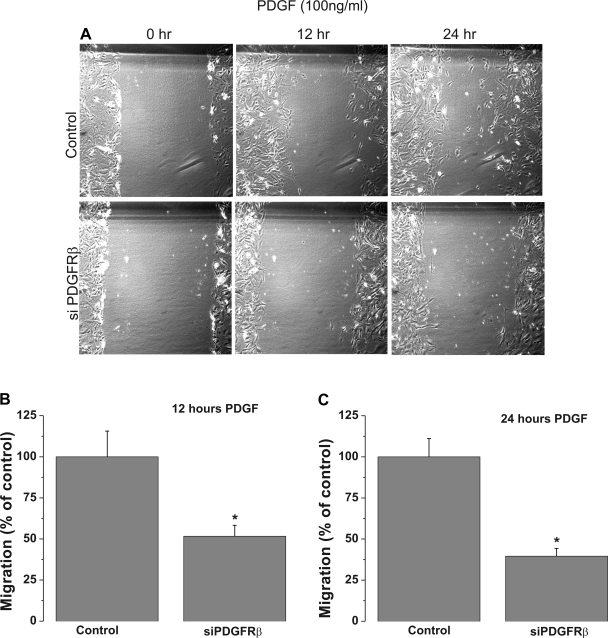

Primary cultured VSMC transfected with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA against different STIM and Orai isoforms were used in a scratch wound assay to assess VSMC migration in response to PDGF stimulation. The cultured rat aortic VSMC used in our laboratory have a doubling time of 22–24 h. To avoid contributions from VSMC proliferation, wound closures were analyzed 12 h after the scratch, when VSMC migration is apparent and proliferation is minimal. siRNA against STIM1 or Orai1 led to a substantial decrease in the wound surface covered by VSMC in response to 100 ng/ml PDGF at 12 and 24 h after the wound: 46.4 ± 10.7% at 12 h for STIM1 and 30.4 ± 6.9% at 12 h for Orai1 (Fig. 5). However, STIM2, Orai2, and Orai3 silencing had no significant effect on VSMC migration (Fig. 6). Figure 7 shows that knockdown of PDGFRβ in VSMC using siRNA caused a substantial decrease in the wound surface covered by VSMC in response to 100 ng/ml PDGF at 12 and 24 h after the scratch compared with scrambled control-transfected cells: 48.31 ± 6.56% at 12 h vs. 60.46 ± 4.78% at 24 h (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5.

A: bright-field views of scratch wound migration assay in serum-free medium containing 100 ng/ml PDGF at 0–24 h after the wound in primary cultured VSMC transfected with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA against STIM1 or Orai1. B and C: data from 3 independent experiments (with 4 wells per condition) at 12 and 24 h after the wound. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 6.

A: bright-field views of scratch wound migration assay in serum-free medium containing 100 ng/ml PDGF at 0–24 h after the wound in primary cultured VSMC transfected with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA against STIM2, Orai2, or Orai3. B and C: data from 3 independent experiments (with 4 wells per condition) at 12 and 24 h after the wound.

Fig. 7.

A: bright-field views of scratch wound migration assay in serum-free medium containing 100 ng/ml PDGF at 0–24 h after the wound in primary cultured VSMC transfected with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA against PDGFRβ. B and C: data from 2 independent experiments (with 4 wells per condition) at 12 and 24 h after the wound. *P < 0.05. Data were generated using PDGFRβ siRNA1; similar results were obtained with PDGFRβ siRNA2 (not shown).

Recent studies showed upregulation of STIM1 and Orai1 proteins in proliferative migratory rat mesenteric arteries compared with quiescent freshly isolated VSMC from the same vascular bed (8), and our group recently reported similar findings in rat aortic VSMC (34). The involvement of STIM1 and Orai1 in PDGF-mediated VSMC migration in vitro prompted us to determine whether STIM and Orai proteins and PDGFRβ are upregulated in proliferative and migratory VSMC in vivo in an animal model of vascular disease.

STIM1, Orai1, and PDGFRβ are upregulated in VSMC during vascular injury.

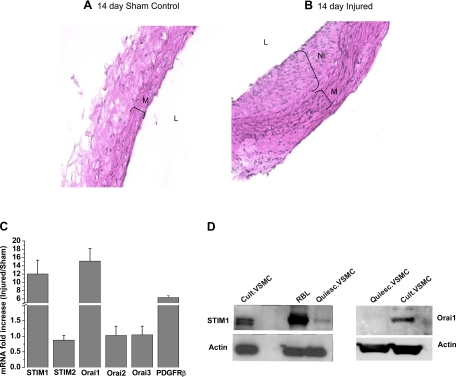

Although the role of Orai1 in neointima formation remains unknown, two recent reports described an essential role for STIM1 in neointima formation following arterial balloon injury in the rat (5, 16). Therefore, we sought to analyze the potential upregulation of STIM1, Orai1, and PDGFRβ in VSMC in vivo in a rat model of vascular injury. We subjected carotid arteries of male rats to balloon injury (see methods) and used sham-operated animals as controls. Our vascular injury model has been well described in numerous published studies over many years (7, 25). In contrast to diet-induced injuries, mechanical injuries are characterized predominantly by VSMC proliferation and migration, with only early and transient lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration and very few detectable immune cells days after the injury (43). Figure 8, A and B, shows representative hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections from sham control or injured carotid vessels 14 days after treatment. Figure 8C shows that mRNA levels encoding STIM1, Orai1, and PDGFRβ are significantly upregulated in injured carotid arteries 14 days after injury compared with noninjured time-matched sham-operated rats: 12.03 ± 3.33 fold for STIM1, 15.13 ± 3.02 fold for Orai1, and 6.33 ± 0.44 fold for PDGFRβ. However, the mRNA levels of STIM2, Orai2, and Orai3 were unaffected. As reported earlier (34), representative Western blots in Fig. 8D show that STIM1 and Orai1 upregulation also occurs in vitro in synthetic cultured VSMC, suggesting that contributions from infiltrating leukocytes to the increase in STIM1 and Orai1 in vivo are unlikely.

Fig. 8.

A and B: hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections of carotid arteries from a time-matched (14 days) noninjured sham control rat and a balloon-injured rat (14 days after injury). M, media; NI, neointima; L, lumen. C: quantitative RT-PCR assessment of mRNA levels of STIM and Orai isoforms and PDGFRβ. mRNAs were isolated from VSMC from sham control and injured rat carotid arteries. Values are expressed as fold increase in mRNA in injured carotid arteries compared with sham control. Data were obtained from 3 control and 3 injured rats that were analyzed in 3–7 independent runs. D: Western blots showing higher levels of STIM1 and Orai1 protein expression in synthetic (cultured) VSMC than in quiescent freshly isolated VSMC, as demonstrated previously (34). Rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells were used in parallel as a positive control.

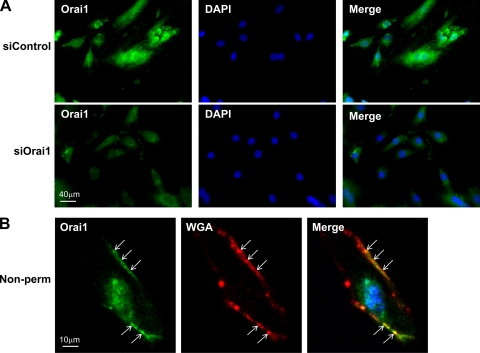

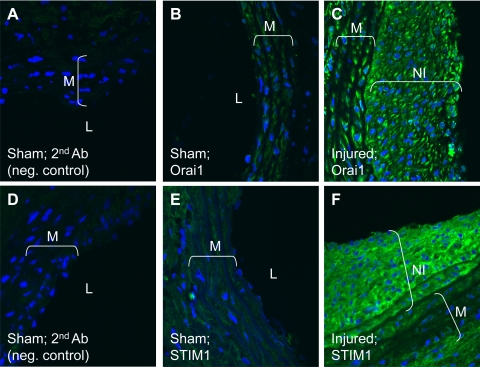

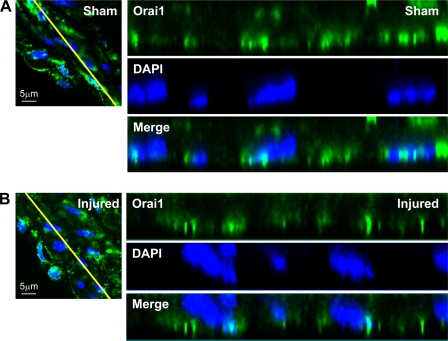

Although we showed in Fig. 2E that Orai1 antibody recognized a single band at the appropriate molecular weight that was decreased 72 h after transfection with specific siRNA against Orai1, strongly arguing for the specificity of this antibody for Orai1, we performed additional experiments in cultured VSMC to further validate the use of Orai1 antibody in immunofluorescence studies in vessel sections. We used a similar Orai1 knockdown approach followed by immunofluorescence staining with anti-Orai1 in cultured synthetic VSMC, as depicted in Fig. 9A. In these experiments, we used standard protocols with Triton X-100 permeabilization and visualization of images using a wide-field microscope under low-magnification conditions (see methods) to process VSMC for immunofluorescence staining. Figure 9A clearly shows a dramatic decrease in Orai1 staining 72 h after treatment with siRNA against Orai1. To address the putative plasma membrane association of Orai1 in VSMC cells, we used immunofluorescence staining under nonpermeabilized conditions and then imaged the cells using a confocal microscope at high magnification. As shown in Fig. 9B, Orai1 staining colocalizes with that of wheat germ agglutinin, a well-known plasma membrane marker in nonpermeabilized cells, suggesting a plasma membrane localization of Orai1. Next, we used immunofluorescence staining to probe for STIM1 and Orai1 protein expression in vessel sections of carotid arteries from sham-operated and injured rats. Figure 10 shows increased protein expression of STIM1 and Orai1 in medial and neointimal VSMC from injured rat carotid arteries (14 days after injury) compared with medial VSMC from noninjured vessels. In Fig. 10, fluorescence images were obtained under similar conditions at low magnification to provide an accurate representation of differences in STIM1 and Orai1 fluorescence levels between the sham-operated and injured carotid vessels. To further characterize the subcellular distribution of Orai1 in tissues from control and injured carotid arteries, we collected vertical sections at 0.5-μm intervals using confocal microscopy (1 Airy unit) at high magnification (×63 lens and zoom factor of 2). ImageJ Volume Viewer plug-in was used to generate a vertical cross section of the tissue slice, which shows a peripheral localization of Orai1, consistent with a plasma membrane association (Fig. 11). Orai1 staining appeared to be more polarized in cells from sections of injured carotid arteries than from sections of control vessels; additional studies are clearly needed to understand the contribution of this polarized Orai1 staining to VSMC migration in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 9.

A: VSMC were transfected with nontargeting siRNA (siControl) or siRNA targeting Orai1 (siOrai1), fixed, and processed for immunofluorescence under permeabilized conditions using anti-Orai1; 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used as a nuclear marker. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. A reduction in Orai1 expression is clearly detected in siOrai1 images. B: VSMC were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence under nonpermeabilized conditions (without Triton X-100) using anti-Orai1 (Orai1), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-Alexa Fluor 594 was used as a plasma membrane marker and DAPI as a nuclear marker, and images were collected using confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate colocalization between Orai1 and WGA at the plasma membrane (Merge, yellow staining). Images were modified in Adobe Photoshop to a higher level of contrast for better visualization.

Fig. 10.

Immunofluorescence staining of carotid artery sections from rats subjected to balloon injury (C and F; 14 days after injury) and control noninjured vessels from sham-operated animals (A, B, D, and E) using anti-Orai1 (B and C) and anti-STIM1 (E and F) antibodies followed by a secondary antibody coupled to FITC. A and D: secondary antibody-alone control. Brackets indicate neointima (NI) in injured vessels. Data are representative of results obtained independently from sections originating from 3 control and 3 injured rats. M, media; L, lumen.

Fig. 11.

Carotid artery sections from rats subjected to balloon injury (B; 14 days after injury) and control noninjured vessels from sham-operated animals (A) were processed for immunofluorescence staining using anti-Orai1; DAPI was used as a nuclear marker. Vertical sections were collected at 0.5-μm intervals using confocal microscopy at high magnification. A representative image is shown at right. ImageJ Volume Viewer plug-in was used to generate a vertical cross section (yellow line) of the tissue slice. Images were modified in Adobe Photoshop to a higher level of contrast for better visualization. Orai1 shows a peripheral subcellular localization, which is consistent with a plasma membrane association.

DISCUSSION

Agonist binding to G protein-coupled receptors or receptor tyrosine kinase activates isoforms of PLC to cause Ca2+ release from the SR and Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space. Receptor-activated Ca2+ entry channels are of two major types: 1) SOC channels activated by the fall of the Ca2+ concentration within the SR through the action of IP3 on its receptor and 2) store-independent channels activated by diverse mechanisms involving, among others, second messengers (31). Identification of the Ca2+-binding protein STIM1 has provided insights into the molecular identity of SOC channels and the signaling mechanisms connecting internal Ca2+ store depletion to this Ca2+ entry (for review see Ref. 35). STIM1, the long-sought Ca2+ sensor in the ER/SR (24, 38) that is capable of oligomerization and reorganization into punctuate structures in defined ER-plasma membrane junctional areas, upon store depletion, signals the activation of the SOC channel at the plasma membrane composed of the membrane protein Orai1 (15, 48). The mechanisms of STIM1-Orai1 coupling are beginning to emerge and appear to involve direct binding of a minimal, highly conserved ∼107-amino acid region of STIM1 to the NH2 and COOH termini of Orai1 to open the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel (23, 29, 32, 51). However, a wide variety of store-dependent and store-independent nonselective cation conductances activated downstream of PLC-coupled receptors have been described by different groups in many cell types, including VSMC (3, 21, 31). Molecular candidates for these cation channels include homomultimers and heteromultimers within Orai and TRP family members, as well as heteromultimers of Orai/TRP isoforms (4, 12, 46).

In vitro and in vivo studies in mouse mutants have established PDGF as a major proproliferative and promigratory growth factor for many cell types of mesenchymal origin, including fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (10). The importance of PDGF signaling during cardiovascular diseases such as restenosis and atherosclerosis is clearly established, whereby PDGF attracts PDGFRβ-expressing medial VSMC, thus promoting their accumulation in the neointima (37). PDGF receptors are receptor tyrosine kinases that couple to PLCγ activation and cause an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ via plasma membrane Ca2+ entry channels. However, the molecular identity of PDGF-activated Ca2+ entry channels in VSMC remained unknown. In this report we show that, in cultured synthetic VSMC, PDGF activates a Ca2+ entry pathway pharmacologically reminiscent of classical SOCE, namely, inhibition by low concentrations of lanthanides (5 μM Gd3+), 2-APB (5 μM), and ML-9 (50 μM). We also show that PDGF-induced Ca2+ entry was substantially inhibited by knockdown of Orai1, STIM1, and PDGFRβ, whereas knockdown of Orai2, Orai3, TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6 had no significant effect, establishing STIM1/Orai1 as the Ca2+ entry route activated in response to PDGFRβ stimulation in VSMC.

The primary cultured VSMC used in this study (also known as synthetic) are dedifferentiated VSMC that have lost their contractile markers and are highly proliferative and migratory compared with the quiescent freshly isolated VSMC (19, 30). These synthetic VSMC recapitulate most of the phenotype and gene expression patterns of proliferative and migratory VSMC found in vivo during vascular diseases such as restenosis and atherosclerosis (19, 30). We and others previously showed increased STIM1 and Orai1 protein expression and upregulated SOCE in these cultured VSMC compared with their quiescent freshly isolated counterparts (8, 34). Here we show that knockdown of STIM1 or Orai1 inhibits VSMC migration in vitro in response to PDGF, whereas STIM2, Orai2, and Orai3 silencing had no significant effect, suggesting that the STIM1-Orai1 pathway is the mediator of PDGF action on PDGFRβ in VSMC. Furthermore, we also show that, during vascular injury, medial and neointimal VSMC upregulate the mRNA and protein expressions of PDGFRβ, STIM1, and Orai1. Two recent studies demonstrated that in vivo silencing of STIM1 with use of viral particles encoding STIM1-targeted short hairpin RNA in rat balloon-injured vessels inhibits neointima formation (5, 16). However, Orai1 upregulation or its contribution to VSMC migratory phenotype in vivo has not been studied. Our results powerfully complement these studies by providing a plausible mechanism for the role of STIM1/Orai1 in neointima formation. Clearly, additional studies are needed to understand the roles of all STIM and Orai isoforms in mediating Ca2+ entry in response to various growth factors/agonists, so we might gain insights into the use of these proteins as targets for vascular disease therapy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Early Career Grant K22 ES-014729 and supplements (K22 ES-014729S1 and K22 ES-014729S2) allocated through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (to M. Trebak).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr. David W. Saffen (Fudan University, Shanghai, China) for generous gifts of reagents and advice. We also gratefully acknowledge the administrative support of Wendy Vienneau and Jo Anne Evans.

Present address of M. Potier: INSERM U921 Nutrition Croissance Cancer, Faculté de Médecine, Bat Dutrochet, 10 Bd Tonnellé, 37032 Tours, France (e-mail: marie.potier-cartereau@univ-tours.fr).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdullaev IF, Bisaillon JM, Potier M, Gonzalez JC, Motiani RK, Trebak M. Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ Res 103: 1289–1299, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert AP, Large WA. Store-operated Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels in smooth muscle cells. Cell Calcium 33: 345–356, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert AP, Saleh SN, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Multiple activation mechanisms of store-operated TRPC channels in smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 583: 25–36, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambudkar IS, Ong HL, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay B, Cheng KT. TRPC1: the link between functionally distinct store-operated calcium channels. Cell Calcium 42: 213–223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubart FC, Sassi Y, Coulombe A, Mougenot N, Vrignaud C, Leprince P, Lechat P, Lompre AM, Hulot JS. RNA interference targeting STIM1 suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat. Mol Ther 17: 455–462, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baryshnikov SG, Pulina MV, Zulian A, Linde CI, Golovina VA. Orai1, a critical component of store-operated Ca2+ entry, is functionally associated with Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and plasma membrane Ca2+ pump in proliferating human arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C1103–C1112, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bendeck MP, Zempo N, Clowes AW, Galardy RE, Reidy MA. Smooth muscle cell migration and matrix metalloproteinase expression after arterial injury in the rat. Circ Res 75: 539–545, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA. Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C779–C790, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature 361: 315–325, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betsholtz C. Insight into the physiological functions of PDGF through genetic studies in mice. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 215–228, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bird GS, Aziz O, Lievremont JP, Wedel BJ, Trebak M, Vazquez G, Putney JW., Jr Mechanisms of phospholipase C-regulated calcium entry. Curr Mol Med 4: 291–301, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birnbaumer L. The TRPC class of ion channels: a critical review of their roles in slow, sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 49: 395–426, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cahalan MD, Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Roos J, Stauderman KA. Molecular basis of the CRAC channel. Cell Calcium 42: 133–144, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feske S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 690–702, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441: 179–185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo RW, Wang H, Gao P, Li MQ, Zeng CY, Yu Y, Chen JF, Song MB, Shi YK, Huang L. An essential role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in neointima formation following arterial injury. Cardiovasc Res 81: 660–668, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwack Y, Feske S, Srikanth S, Hogan PG, Rao A. Signalling to transcription: store-operated Ca2+ entry and NFAT activation in lymphocytes. Cell Calcium 42: 145–156, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House SJ, Ginnan RG, Armstrong SE, Singer HA. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II δ-isoform regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C2276–C2287, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.House SJ, Potier M, Bisaillon J, Singer HA, Trebak M. The non-excitable smooth muscle: calcium signaling and phenotypic switching during vascular disease. Pflügers Arch 456: 769–785, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.House SJ, Singer HA. CaMKII-δ isoform regulation of neointima formation after vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 441–447, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue R, Jensen LJ, Shi J, Morita H, Nishida M, Honda A, Ito Y. Transient receptor potential channels in cardiovascular function and disease. Circ Res 99: 119–131, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res 88: 325–332, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawasaki T, Lange I, Feske S. A minimal regulatory domain in the C terminus of STIM1 binds to and activates ORAI1 CRAC channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385: 49–54, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 15: 1235–1241, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malabanan KP, Kanellakis P, Bobik A, Khachigian LM. Activation transcription factor-4 induced by fibroblast growth factor-2 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor-A transcription in vascular smooth muscle cells and mediates intimal thickening in rat arteries following balloon injury. Circ Res 103: 378–387, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maruyama Y, Nakanishi Y, Walsh EJ, Wilson DP, Welsh DG, Cole WC. Heteromultimeric TRPC6-TRPC7 channels contribute to arginine vasopressin-induced cation current of A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 98: 1520–1527, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J Physiol 586: 185–195, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. STIM1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J Physiol 579: 703–715, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muik M, Fahrner M, Derler I, Schindl R, Bergsmann J, Frischauf I, Groschner K, Romanin C. A cytosolic homomerization and a modulatory domain within STIM1 C-terminus determine coupling to ORAI1 channels. J Biol Chem 284: 8421–8426, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 84: 767–801, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev 85: 757–810, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park CY, Hoover PJ, Mullins FM, Bachhawat P, Covington ED, Raunser S, Walz T, Garcia KC, Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS. STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136: 876–890, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP. ORAI and store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 744–749, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potier M, Gonzalez JC, Motiani RK, Abdullaev IF, Bisaillon JM, Singer HA, Trebak M. Evidence for STIM1- and Orai1-dependent store-operated calcium influx through I CRAC in vascular smooth muscle cells: role in proliferation and migration. FASEB J 23: 2425–2437,2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potier M, Trebak M. New developments in the signaling mechanisms of the store-operated calcium entry pathway. Pflügers Arch 457: 405–415, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium 7: 1–12, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raines EW. PDGF and cardiovascular disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 15: 237–254, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 169: 435–445, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL, Mignen O. ARC channels: a novel pathway for receptor-activated calcium entry. Physiology (Bethesda) 19: 355–361, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL, Mignen O. STIM1 and the noncapacitative ARC channels. Cell Calcium 42: 183–191, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Ca2+-store-dependent and -independent reversal of Stim1 localization and function. J Cell Sci 121: 762–772, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweeney M, Yu Y, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, McDaniel SS, Yuan JX. Inhibition of endogenous TRP1 decreases capacitative Ca2+ entry and attenuates pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L144–L155, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szocs K, Lassegue B, Sorescu D, Hilenski LL, Valppu L, Couse TL, Wilcox JN, Quinn MT, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Upregulation of Nox-based NAD(P)H oxidases in restenosis after carotid injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 21–27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trebak M, Bird GS, McKay RR, Putney JW., Jr Comparison of human TRPC3 channels in receptor-activated and store-operated modes. Differential sensitivity to channel blockers suggests fundamental differences in channel composition. J Biol Chem 277: 21617–21623, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trebak M, Hempel N, Wedel BJ, Smyth JT, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Negative regulation of TRPC3 channels by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of serine 712. Mol Pharmacol 67: 558–563, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trebak M, Lemonnier L, Smyth JT, Vazquez G, Putney JW., Jr Phospholipase C-coupled receptors and activation of TRPC channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol 593–614, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trebak M, St J Bird G, McKay RR, Birnbaumer L, Putney JW., Jr Signaling mechanism for receptor-activated canonical transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels. J Biol Chem 278: 16244–16252, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312: 1220–1223, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wamhoff BR, Bowles DK, Owens GK. Excitation-transcription coupling in arterial smooth muscle. Circ Res 98: 868–878, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xi Q, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, Chapman KE, Waters CM, Hassid A, Jaggar JH. IP3 constricts cerebral arteries via IP3 receptor-mediated TRPC3 channel activation and independently of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Circ Res 102: 1118–1126, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan JP, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Choi YJ, Worley PF, Muallem S. SOAR and the polybasic STIM1 domains gate and regulate Orai channels. Nat Cell Biol 11: 337–343, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]