Abstract

ATP-binding cassette A3 (ABCA3) is a lipid transport protein required for synthesis and storage of pulmonary surfactant in type II cells in the alveoli. Abca3 was conditionally deleted in respiratory epithelial cells (Abca3Δ/Δ) in vivo. The majority of mice in which Abca3 was deleted in alveolar type II cells died shortly after birth from respiratory distress related to surfactant deficiency. Approximately 30% of the Abca3Δ/Δ mice survived after birth. Surviving Abca3Δ/Δ mice developed emphysema in the absence of significant pulmonary inflammation. Staining of lung tissue and mRNA isolated from alveolar type II cells demonstrated that ∼50% of alveolar type II cells lacked ABCA3. Phospholipid content and composition were altered in lung tissue, lamellar bodies, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. In adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice, cells lacking ABCA3 had decreased expression of mRNAs associated with lipid synthesis and transport. FOXA2 and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α, transcription factors known to regulate genes regulating lung lipid metabolism, were markedly decreased in cells lacking ABCA3. Deletion of Abca3 disrupted surfactant lipid synthesis in a cell-autonomous manner. Compensatory surfactant synthesis was initiated in ABCA3-sufficient type II cells, indicating that surfactant homeostasis is a highly regulated process that includes sensing and coregulation among alveolar type II cells.

Keywords: gene regulation, lipids, lung, compensation

pulmonary surfactant reduces surface tension at the air-liquid interface in the alveolus, thereby maintaining lung volumes during the respiratory cycle. Surfactant consists of lipids and associated proteins that are required for surfactant function. Notably, surfactant proteins (SP) B and C (encoded by SFTPB and SFTPC) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) A3 (ABCA3) play critical roles in surfactant synthesis and function. Various autosomal-recessive mutations in SFTPB and ABCA3 cause fatal respiratory distress in human newborns due to the lack of surfactant (20, 42). In some cases, ABCA3 mutations are associated with interstitial lung diseases in older children (12, 17, 54). Histological analysis of lungs of such patients showed interstitial fibrosis. Heterozygosity for ABCA3 mutations increased the severity of interstitial lung disease associated with mutations in SFTPC, indicating that alterations in ABCA3 may influence the pathogenesis of lung diseases (10).

Coordination of the synthesis and packaging of surfactant components is essential for the transition to air breathing at birth and thereafter. Surfactant content and function are regulated at multiple levels, including synthesis, processing, intracellular transport, assembly, and storage of surfactant components, surfactant secretion, and catabolism of lipids and proteins. Expression of surfactant proteins and regulation of lipid metabolism during development are dependent on a number of transcription factors that are expressed in respiratory epithelial cells (6, 14, 15, 29, 30, 47). Less is known regarding control of surfactant lipid homeostasis in the postnatal lung. Maintenance of surfactant lipid content during lung injury may involve intra- and extracellular sensing modules capable of detecting and regulating lipid content and trafficking.

ABC proteins are members of a large family of transporters associated with ATP-dependent translocation of various substrates across cellular membranes. ABCA3 is expressed in various organs, including lung, brain, and kidney (32, 44). In the lung, Abca3 mRNA increases dramatically prior to birth (44). Abca3 gene expression is regulated by glucocorticoids (53) and cis-acting cassettes that mediate pulmonary cell- and lipid-sensitive pathways (7), allowing surfactant homeostasis at birth and thereafter. ABCA3 is a 1,704-amino acid and 190-kDa protein, highly expressed in alveolar type II cells, where it is present in the limiting membrane of lysosomal-derived intracellular inclusions termed lamellar bodies (LBs) (32, 52, 55). Abnormalities in lipid content and function were observed in surfactant from patients with ABCA3-related pulmonary disease (20). Deletion of the Abca3 gene in mouse models resulted in respiratory failure after birth, which was caused by the absence of surfactant in the alveoli. Loss of mature LBs in Abca3 gene-deleted mice was also observed and was consistent with findings in human infants with mutations in ABCA3 (2, 13, 19, 23). Taken together, ABCA3 is required for LB formation and pulmonary surfactant function.

While deletion of the Abca3 gene in mice demonstrated its requirement at birth, little is known about the effects of Abca3 deficiency in adult lung function. In this study, the Abca3 gene was conditionally deleted in respiratory epithelial cells. Deletion of Abca3 altered lung lipid content and synthesis. Maintenance of surfactant function in Abca3-deleted mice after birth was associated with compensatory lipid synthesis in nontargeted type II cells, revealing a novel compensatory system that senses surfactant deficiency caused by cell-selective deletion of Abca3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene construction for Abca3 floxed mouse.

To generate a conditional Abca3 floxed mutant allele, a 14.4-kb region of the mouse gene was subcloned from a positively identified bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone from inGenious Targeting Lab (Stony Brook, NY) and used to construct the targeting vector. The construct was designed such that the short-homology arm extended 1.9 kb 3′ of the loxP-floxed neomycin (Neo) cassette, in intron 7/8. The long-homology arm extended 12.5 kb 5′ of the Neo cassette, and a single loxP site was inserted in intron 3/4, 5′ of exon 4. The target region was 4.6 kb and included exons 4, 5, 6, and 7 (Fig. 1A). A targeting construct was generated with Neo-resistance (neoR) gene as a selective marker. The linearized targeting construct was electroporated into eukaryotic stem cells and grown in the antibiotic G418. Surviving clones were screened for homologous recombination by Southern and PCR analysis. Ten positive clones were detected in 288 samples analyzed. Eukaryotic stem cells from three positively identified loxP-floxed Abca3 clones (Abca3flx) were injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice, and germ-line transmission of the Abca3flx allele was achieved from all clones injected and backcrossed with C57BL6 for at least three generations.

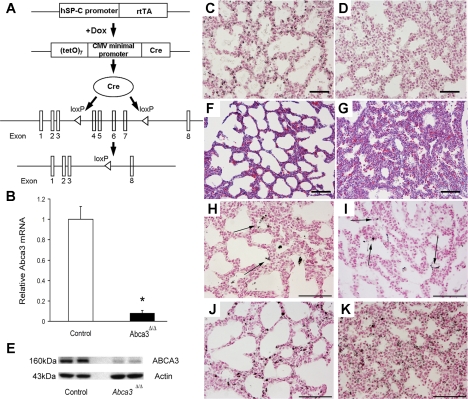

Fig. 1.

Conditional deletion of ATP-binding cassette A3 (Abca3) in respiratory epithelium. A: triple-transgenic mice were produced in which doxycycline (Dox) activates reverse tetracycline transactivator (rtTA) expressed under control of the surfactant protein C (hSP-C) promoter. The rtTA then activates Cre, which excises exons 4–7 and religates the target gene, inactivating the Abca3 gene permanently. Dams were treated with doxycycline from embryonic (E) day 6.5 (E6.5) to E14.5 to delete the Abca3 gene from respiratory epithelial cells. CMV, cytomegalovirus. B: quantitative RT-PCR was performed to estimate Abca3 mRNA in whole lung homogenate from newborn [postnatal day 0 (PND0)] Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice and normalized to β-actin mRNA. Results are expressed as means ± SE of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.01 vs. control littermates. Immunostaining for ABCA3 was performed on E18.5 Abca3Δ/Δ and control lungs. While ABCA3 was detected in control lungs (C), ABCA3 was rarely detected in Abca3Δ/Δ mice (D). Scale bars, 100 μm. Western blot analysis demonstrated a marked decrease in ABCA3 protein in Abca3Δ/Δ lungs compared with control (E). Atelectasis and thickened mesenchyme were observed in PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice (G) compared with control littermates (F). Scale bars, 100 μm. Immunostaining for mature surfactant protein (SP) B (H and I) and SP-C (J and K) was similar in PND0 control (H and J) and Abca3Δ/Δ mice (I and K). Scale bars, 200 μm. Photomicrographs are representative of ≥3 per group.

SP-C-rtTA (line 2)/(tetO)7CMV-Cre/Abca3flx/flx triple-transgenic mice were generated as described previously (34, 35, 39, 49). In the presence of doxycycline, exons 4, 5, 6, and 7 of the Abca3 gene were permanently deleted from respiratory epithelial cells prior to birth (Abca3Δ/Δ mice; Fig. 1A). For genotyping, DNA was purified from the tail of experimental mice, and PCR was performed for Abca3flx, SP-C-rtTA, and (tetO)7CMV-Cre genes using the following primers: 5′-AGC ACT TTT CCC TCT CTG GCC TTG AG-3′ and 5′-TGC CCA CCC AGC ACC ATG CT-3′ for Abca3flx, 5′-GAC ACA TAT AAG ACC CTG GCTA-3′ and 5′-AAA ATC TTG CCA GCT TTC CC-3′ for SP-C-rtTA, and 5′-TGC CAC CAA GTG ACA GCA ATG-3′ and 5′-AGA GAC GGA AAT CCA TCG CTCG-3′ for (tetO)7CMV-Cre. Abca3-deleted transgenic (Abca3Δ/Δ) mice and nondeleted (SP-C-rtTAtg/wt, Abca3flx/flx, control) littermates were used for the experiments. FVB/N-TgN(EIIa-Cre)C5379Lmgd mice carrying a Cre transgene, under the control of the adenovirus EIIa promoter, which targets expression of Cre recombinase to the early mouse embryo, were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Double-transgenic mice were generated by mating EIIa-Crewt/tg/Abca3flx/wt to Abca3flx/flx mice. Abca3flx/flx littermates lacking the Cre gene served as controls.

Animal husbandry and doxycycline administration.

Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation. All animals were housed in humidity- and temperature-controlled rooms on a 14:10-h light-dark cycle. Mice were allowed food and water ad libitum. There was no serological evidence of pulmonary pathogens or bacterial infections in sentinel mice maintained within the colony. Gestation was dated by detection of the vaginal plug [as embryonic (E) day 0.5 (E0.5)] and correlated with the weight of each pup at the time of death. Doxycycline (625 mg/kg; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) was administered to the dams in the food from E6.5 to E14.5, resulting in extensive deletion of Abca3 in respiratory epithelial cells. Mice were then fed normal food.

Tissue preparation, histology, and immunohistochemistry.

Lung tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry were performed essentially as described previously (28, 46). Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Primary antibodies were used at the following dilutions: surfactant protein (SP)-B (1:2,000, rabbit polyclonal; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), proSP-C (1:4,000, rabbit polyclonal; AB3428, Chemicon), ABCA3 (1:1,000, rabbit polyclonal; Seven Hills Bioreagents), FOXA2 (1:4,000 and 1:8,000, rabbit polyclonal; Seven Hills Bioreagents), and cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000, rabbit polyclonal; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Vector, Burlingame, CA). All experiments are representative of findings from at least four Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice. Lung sections were stained with orcein to detect elastic fibers (Poly Scientific, Bay Shore, NY).

Transmission electron microscopy.

Lung tissue from postnatal day 0 (PND0) and 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice and littermate controls was fixed in modified Karnovsky's fixative consisting of 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and 0.1% calcium chloride (pH 7.3). Adult tissue was stained en bloc with 4% uracyl acetate, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, dehydrated, and embedded in epoxy resin (EMbed 812, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, PA), as previously described (56). Ultrathin sections were postfixed with uracyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed in Morgagni 268 and Hitachi 7600 transmission electron microscopes (TEM), and digitized images were collected with an Advantage Plus 2K × 2K TEM equipped with a charge-coupled device digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA).

Morphometry.

Morphometric measurements were performed on 9 mo-old mice of both genotypes. The overall proportion [%fractional (%Fx) area] of respiratory parenchyma and air space was determined by a point-counting method (50). Measurements were performed on two sections taken at intervals throughout the left, right upper, and right lower lobes. Slides were viewed with an ×20 objective. Images (fields) were acquired randomly with a digitalized camera and quantified using MetaMorph imaging software (version 7.5, Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). A computer-generated, 121-point lattice grid was superimposed on each field, and the number of intersections (points) falling over respiratory parenchyma (alveoli and alveolar ducts) or air space was counted. Points falling over bronchioles, large vessels, and smaller arterioles and venules were excluded from the study. %Fx area was calculated by dividing the number of points for each compartment (n) by the total number of points contained within the field (N) and then multiplying by 100: %Fx area = n/N × 100. Fifteen random fields per section were analyzed to gather the data. The x- and y-coordinates for each field measured were selected by a random-number generator (Microsoft Excel 2003, Redmond, WA).

The number of ABCA3-stained cells was determined by a point-counting method. Five mice of both genotypes were studied. Measurements were performed throughout the left, right upper, and right lower lobes, and the number of ABCA3-stained cells was counted manually. The density of ABCA3-stained cells was calculated by dividing the number of ABCA3-stained cells by alveolar area (mm2). Fifteen fields per section were analyzed. The x- and y-coordinates for each field measured were selected by a random-number generator. Bronchioles, large vessels, and smaller arterioles and venules were excluded.

The cross-sectional area of LBs in alveolar type II cells from 9-mo-old control and Abca3Δ/Δ mice was determined from ultrathin (90-nm-thick) sections cut from one to two Epon blocks from each group (n = 1 for control and n = 3 for Abca3Δ/Δ mice) and transferred to 200-mesh copper grids. Ten electron micrographs were randomly selected from one to two sections per block. Each electron micrograph was coded according to genotype and digitally acquired at a final magnification of ×10,000. The cross-sectional areas of all LBs were determined using the region measurement function in MetaMorph imaging software (version 7.5).

The percentage of type II cells with or without LBs was assessed by TEM of tissue from 9-mo-old control and Abca3Δ/Δ mice. A total of 292 type II cells found in 1–2 grids from 3 different Abca3Δ/Δ mice were analyzed.

Isolation of alveolar type II epithelial cells.

Alveolar type II cells were isolated from 9-mo-old control and Abca3Δ/Δ mouse lung with use of collagenase and differential plating, as described previously (38). Type II cells were used 2 h after isolation for RNA analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting.

After isolation, alveolar type II cells were stained for 10 min in the presence of 1 μM Nile red (NR). Cells were then washed three times in PBS and brought to a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/ml in sorting buffer [1× PBS (Ca2+/Mg2+ free), 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 1% fetal bovine serum, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml]. Cells were sorted and analyzed by a FACSAria II sorter (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) within 2 h of staining. Excitation was at 533 nm using a yellow-green laser, and emission was collected at 628 nm. A more intense red fluorescence of the phospholipid-enriched cells is obtained, because the emission maxima wavelength of phospholipids stained with NR is longer than that observed for neutral lipids (9, 21). NR-positive cells were initially gated on the basis of side scatter and mean fluorescence intensity of the NR signal. Data were exported and analyzed with FACSDiVa software (Becton Dickinson).

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

Nine-mo-old mice (n = 5/group) were anesthetized and killed by exsanguination. Tracheas were cannulated, and five 1-ml aliquots of 0.9% NaCl were flushed into the lungs and withdrawn by syringe three times for each aliquot. The volumes of recovered bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (BALF) from all the groups were similar. After centrifugation, BAL cells were counted using a hemocytometer to determine total BAL cell concentration. BAL cells were used for RNA extraction, or, after cytospin, cells were stained to determine differential cell counts (Diff-Quik, Dade Behring, Miami, FL).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from whole lung homogenate of PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice or isolated lung alveolar type II cells or BAL cells of adult mice with use of RNeasy Protect Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were obtained from five control or Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Quantitative PCRs using Taqman probes (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA) were performed with primer sets specific for Abca3 (Mm00550501_m1), surfactant protein (Sftp) Sftpa1 (Mm00499170_m1), Sftpb (Mm00455681_m1), Sftpc (Mm00488144_m1), fatty acid synthase (Fasn, Mm01253292_m1), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (Scd1, Mm01197142_m1), lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 (Lpcat1, Mm00461015_m1), fatty acid-binding protein 5 (Fabp5, Mm00783731_s1), choline phosphate cytidylyltransferase 1 (Pcyt1a, Mm00447774_m1), napsin A aspartic peptidase (Napsa, Mm00492829_m1), steroidogenic acute regulatory domain protein (Stard) 2 (Stard2, Mm00476629_m1), Stard7 (Mm00460536_m1), Stard9 (Mm00626196_m1), Stard10 (Mm00502345_m1), Abca1 (Mm00442646_m1), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (Hmgcs1, 00524111_m1), nuclear factor of activated T cells (Nfatc3, Mm01249200_m1), NK2 homeobox 1 Nkx2.1 (Mm00447558_m1), forkhead box A2 (Foxa2, Mm01976556_s1), CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α (Cebpa, Mm01265914_s1), macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (Mip1a, Mm00441258), transforming growth factor-β1 (Tgfb1, Mm03024053), TNFα (Tnfa, Mm00443258_m1), IL-1β (Il-1b, Mm01336189_m1), and matrix metallopeptidase 12 (Mmp12, Mm00838401_g1). A probe set for 18S rRNA was used as the normalization standard. The PCR and relative quantifications were performed using 25 ng of cDNA per reaction in a real-time PCR system (model 7300, Applied BioSystems). Relative quantification data from quantitative PCR analysis were statistically analyzed using Student's t-tests.

Western blot analysis for ABCA3.

ABCA3 expression was quantified by Western blot analysis in whole lung homogenate. Samples were obtained from PND0 control and Abca3Δ/Δ mice (n = 3 for each genotype). Proteins were extracted using NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL), diluted in Laemmli buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing condition. After transfer, the membrane was blocked for 2 h at room temperature in PBS [20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6) and 137 mM NaCl] + 0.2% Tween 20 containing 5% skim milk and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following dilutions of antibody were used: anti-ABCA3 (COOH-terminal region, 1:1,000, rabbit polyclonal; a kind gift from Dr. Inagaki, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) (52) and actin (1:1,000, goat polyclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) were used at 1:5,000 dilutions. Immunoreactive bands were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK).

LB preparation.

Nine-month-old mice (n = 8/group) were anesthetized and killed by exsanguination. After BAL, the lungs were rapidly removed and chilled in 0.25 M sucrose in Tris buffer (0.01 M Tris·HCl, 0.001 M CaCl2, 0.002 M MgSO4, and 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4). The right lobes were minced finely with scissors and homogenized with 0.25 M sucrose by use of a loosely fitting Teflon plunger (clearance of ∼0.09 mm) with a Pyrex Potter homogenizer. Debris and intact cells were spun down at 2,000 rpm (600 g) for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was strained through lens paper. The crude lung homogenate was brought to 1.2 M sucrose by the addition of 2.5 M sucrose. Four-milliliter aliquots were placed in polyallomer tubes and overlaid by a sucrose gradient consisting of 3 ml of 0.7 M sucrose buffer, 7 ml of 0.5 M sucrose buffer, and 3 ml of 0.3 M sucrose. The tubes were centrifuged for 3 h at 104,000 g at 4°C in a Beckman L-70 ultracentrifuge with an SW28 swinging-bucket rotor. After centrifugation, the LB fraction was collected from the top and stored at −80°C.

Analysis of surfactant components.

Saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) was measured in homogenized whole lung tissue from PND0 mice (n = 4–6 mice for each genotype) as previously described (3). The phospholipids in chloroform-methanol extracts of homogenized lung were separated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography for compositional analyses as previously described (26). The spots were visualized with iodine vapor, scraped, and assayed for phosphorus content as previously described (26).

Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry of phospholipid molecular species and phosphatidylcholine synthesis.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of methyl-D9-choline chloride (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) 3 h before they were killed. Phospholipids were extracted from BALF, lavaged lung tissue, and LBs with chloroform and methanol according to Bligh and Dyer (8) after addition of the following internal standards: phosphatidylcholine (PC14:0/14:0, 10 pmol), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE14:0/14:0, 4 pmol), phosphatidylglycerol (PG14:0/14:0, 2 pmol), and phosphatidylserine (PS14:0/14:0, 2 pmol). Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry of phospholipids was performed as previously described (36). In addition, incorporation of methyl-D9-choline as a measure of PC synthesis in the various tissue fractions was determined by precursor scan of mass-to charge ratio (m/z) 193 (P193) expressed relative to total PC, determined as the sum of precursor scan of m/z 184 (P184) and P193 (5). The volumes of recovered BALF from all the groups were similar. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

RNA microarray analysis.

For Affymetrix MicroArray, E18.5 lung RNAs from Abca3Δ/Δ mice and littermate controls were prepared using the RNeasy Protect Mini kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA was treated with DNase at room temperature for 15 min. Lung cRNA was hybridized to the Murine Genome 430 2.0 Array (consisting of 45,000 probe sets representing >34,000 mouse genes; Affymetrix) using the manufacturer's protocol. Affymetrix MicroArray Suite version 5.0 was used to scan and quantitate the gene chips using default scan settings. Normalization was performed using the Robust Multichip Average model, which consists of three steps: background adjustment, quartile normalization, and summarization (24, 25). Microarray analysis was performed with the software package BRB Array Tools, developed by the Biometric Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html). Differentially expressed genes were identified using a univariate F test and permutation test (n = 100) with a significance level of 0.05. Data were prefiltered by excluding probe sets as follows: 1) those whose expression differed ≤1.2 from the median in 80% of the samples, 2) those whose expression data were missing in >50% of the samples, or 3) those with >70% of absent calls by the Affimetrix algorithm in six samples. Gene Ontology and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis were performed using the publicly available web-based tool DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery) (16). Gene frequency and probability in each functional category were calculated by Fisher's Exact test using Mouse Genome 430 2.0 as background control. Biological association networks were built using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Student's t-test was used to determine the levels of difference between groups. Values for all measurements are expressed as means ± SE, and P values for significance are indicated for each experiment.

RESULTS

Abca3 is required for postnatal adaptation to air breathing.

Abca3 mRNA was previously detected in alveolar type II cells in the murine lung, as well as in other organs, including brain and kidney (32, 44). To identify the role of Abca3 in alveolar type II cells, triple-transgenic SP-C-rtTAtg/wt, TetO-Cretg/wt, and Abca3flx/flx (Abca3Δ/Δ) mice were produced; in these mice, Abca3 was selectively and permanently deleted in the respiratory epithelium following administration of doxycycline to the dam from E6.5 to E14.5 (Fig. 1A). Analysis of Abca3 gene expression demonstrated a dramatic reduction of Abca3 mRNA and ABCA3 protein in newborn (PND0) Abca3Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 1, B–E); 67% of PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice died at birth. The lungs of the Abca3Δ/Δ mice that died at PND0 failed to inflate. Atelectasis was observed (Fig. 1, F–G). Immunostaining for mature SP-B and proSP-C were similar in Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice (Fig. 1, H–K). To confirm the targeting of the conditional Abca3 floxed mutant allele, EIIa-Cretg/wt, Abca3flx/flx mice wherein Abca3 is deleted prior to implantation in the uterine wall, died soon after birth from respiratory failure, confirming the recombination of the Abca3flx allele and supporting its requirement for the transition to air breathing at birth (data not shown).

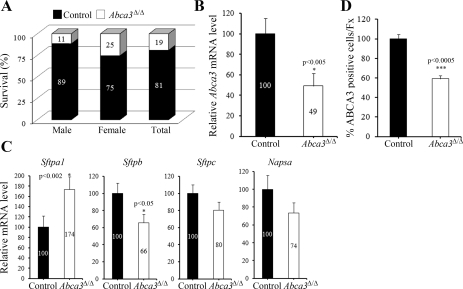

Adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice develop emphysema.

Approximately 33% of the Abca3Δ/Δ mice survived postnatally and to 9 mo of age. Postnatal survival was better in females than males (Fig. 2A). The efficiency of Abca3 deletion in alveolar type II cells in surviving mice at 9 mo was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry. Both Abca3 mRNA and the number of cells stained for ABCA3 were decreased by ∼50% in type II cells isolated from adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control littermates (Fig. 2, B and D), indicating the heterogeneity of Abca3 targeting. Deletion of Abca3 in adult mice altered surfactant-associated protein mRNA expression. While a marked decrease in Sftpb was observed in Abca3Δ/Δ lungs, Sftpc and Napsa were similar in both groups of mice (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Sftpa1 was significantly increased in Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control littermates.

Fig. 2.

Survival after partial deletion of Abca3. Survival rate was determined in 9-mo-old male and female control and Abca3Δ/Δ mice (A). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to estimate Abca3 (B) and surfactant-associated protein (Sftpa1, Sftpb, Sftpc, Napsa) mRNAs (C) in alveolar type II cells isolated from adult control or Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA. To assess the number of type II cells expressing ABCA3, lung sections of 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice and control littermates were prepared and immunostained for ABCA3. Numbers of ABCA3-stained cells (D) were calculated as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE of 4 animals per group.

Surviving Abca3Δ/Δ mice developed normally after birth. While alveolarization was unchanged at 4 wk of age, air space enlargement was observed in 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 3, A–D). The relative proportion of respiratory parenchyma (Fig. 3E) and air space (Fig. 3F; fractional area) were altered in 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control littermates, with a significant increase in the fractional area of air space (P < 0.002) in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. The enlargement of alveoli was associated with alterations in the distribution and structure of elastic fibers. Thickened elastin fibers were observed surrounding enlarged air spaces in Abca3Δ/Δ mice, in contrast to fine elastin fibers in septae of normal lung (data not shown). Inflammation was not readily apparent in the Abca3Δ/Δ mice, and total cell counts were similar in lung lavage fluid (Fig. 3G), wherein monocytes/macrophages were the main cell population. Inflammatory cytokine mRNA levels in Abca3Δ/Δ mice were not statistically different from those in control littermates (Fig. 3H). There was no histological or serological evidence of infection, and sentinel mice did not harbor viral or bacterial pathogens.

Fig. 3.

Adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice develop emphysema. Lung sections of Abca3Δ/Δ (B and D) and control littermates (A and C) were prepared from 4-wk-old (A and B) and 9-mo-old (C and D) mice and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. While no histological abnormalities were observed in 4-wk-old mice, Abca3Δ/Δ mice developed emphysema by 9 mo of age (D, inset). Photomicrographs are representative of ≥4 individual mice at each time. Scale bars, 500 μm. Magnification of inset is 3 times the original magnification. Changes in fractional areas (%Fx area) of respiratory parenchyma (E) and air space (F) were determined in 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.001. G: cell populations in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid (BALF) from adult Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates. BALF cell counts were similar in Abca3Δ/Δ mice and control mice. mRNAs for selected cytokines were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR in isolated BAL cells from lungs of adult Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates and normalized to β-actin mRNA, indicating no evidence of activation of inflammation (H). Values are means ± SE of 5 animals per group. *P < 0.01 vs. control littermates. NS, no statistical difference.

Deletion of Abca3 alters lamellar body formation and surfactant composition.

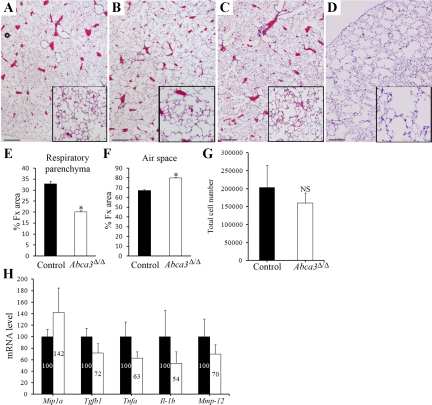

In newborn mice, in contrast to control littermates, LBs were not observed in type II cells from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice that died at birth from respiratory distress (Fig. 4, A and B). Alveolar type II cells from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice contained more glycogen, and some contained atypical lipid structures. Secreted surfactant and tubular myelin were absent from the alveoli of the newborn Abca3Δ/Δ mice, while evidence of type I cell injury and early hyaline membrane formation, consistent with respiratory distress syndrome, was also detected by TEM (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Deletion of Abca3 influences lamellar body (LB) formation in adult type II epithelial cells. Electron microscopy was used to study lung sections from PND0 control (A) and Abca3Δ/Δ (B) and adult control (C) and Abca3Δ/Δ (D–J) mice. Type II cells from PND0 control mice contained numerous LBs (arrow; A, inset). LBs were absent in PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Glycogen (Gly) was increased in type II cells from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice (B). Membranous structures were present in the cytoplasm of type II cells from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice (B, inset). In adult mice, sizes and numbers of LBs were consistent in type II cells from control mice (C). D–J: heterogeneity of LB size and numbers in type II cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Subsets of type II epithelial cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice lacked LBs and contained abnormal electron-dense bodies (arrows, E and F) or contained multiple LBs (D) or abnormal (∗, I) or extremely large (J) LBs. Lipid vesicles were visualized in cytoplasm of subsets of type II epithelial cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice (arrowhead, G and H). Original magnification: ×10,000 (A–C), ×20,000 (E, G, and H), ×40,000 (D and F). N, nucleus; m, mitochondria.

Numerous LBs were observed in 9-mo-old control mice (Fig. 4C). Although the average LB cross-sectional area was similar between control and Abca3Δ/Δ mice, variations in size and number of LBs were seen in the Abca3Δ/Δ mice (see supplemental Fig. 1 in the online version of this article). In Abca3Δ/Δ mice, two distinct subsets of type II cells were altered. One subset of type II cells contained no LBs (68%), but liposome-like vesicular structures of intermediate electron density with electron-dense inclusions were observed (Fig. 4, E and F). In addition, this subset contained variable numbers of lipid inclusions that were absent from the controls (Fig. 4, G and H). The second subset of type II cells contained normal (26%) and “giant” (6%) LBs, either single lamellar-like bodies or larger structures containing several LBs (Fig. 4, D, I, J; see supplemental Fig. 1). These data support the concept that changes in surfactant lipid homeostasis in nondeleted type II cells may compensate for the absence of LBs in cells in which Abca3 was deleted.

Effect of deletion of Abca3 on phospholipid composition and synthesis.

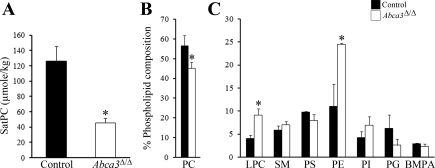

Consistent with the ultrastructure alterations observed in newborns, Sat PC (Fig. 5A), PC, and, to a lesser extent, PG content were decreased in lungs from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 5, B and C); lung lysophosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine contents were increased.

Fig. 5.

Surfactant phospholipid composition is altered in newborn Abca3Δ/Δ mice. A: saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) was decreased in whole lung tissue from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice. *P < 0.05. B and C: relative distribution of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), sphingomyelin (SM), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and bis(monoacylglycerol)phosphate (BMPA) in lung tissue from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates as determined by 2-dimensional thin-layer chromatography, as described previously (26). Values are means ± SE of 4 animals per group. *P < 0.05.

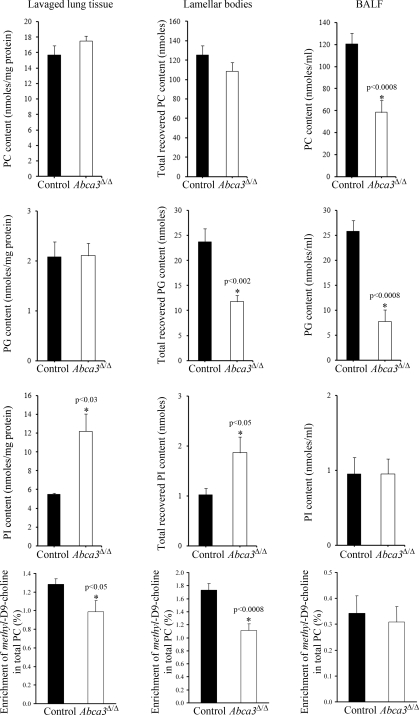

Despite the altered morphology of type II cells in the adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice, the concentration of total PC in lavaged lungs and LBs, calculated as the sum of individual molecular species determined by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry, was not significantly different in adult Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice (Fig. 6). The concentration of total PC was, however, decreased by 50% in BALF from adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Both groups of mice showed a comparable sequential enrichment pattern of surfactant-specific PC species from lavaged lungs, through LBs to BALF. Comparison of profiles of PC synthesis and concentration indicated that acyl remodeling mechanisms were also unaltered in Abca3Δ/Δ compared with control mice (data not shown). PC synthesis, calculated as the sum of methyl-D9-choline incorporation into PC molecular species after 3 h of labeling, was decreased by 20% in lavaged lung in Abca3Δ/Δ mice, from 1.28 ± 0.06 to 1.00 ± 0.12% total PC (mean ± SE, P < 0.05; Fig. 6). Incorporation of stable isotope into PC in isolated LBs was 1.73 ± 0.10% total PC in controls and was significantly decreased in lungs of Abca3Δ/Δ mice to 1.11 ± 0.10% total PC (mean ± SE, P < 0.001). In contrast, methyl-D9-choline enrichment in BALF PC was essentially identical in Abca3Δ/Δ mice and controls, although newly synthesized PC was considerably less abundant in BALF than in lavaged tissue or LB at 0.34 ± 0.07 vs. 0.31 ± 0.06% total PC. PG content was markedly decreased in LBs and BALF fractions, but not in lung parenchyma (Fig. 6). In agreement with previous analyses (37), this detailed lipidomic characterization showed that disaturated PG species consistently represented <20% of PG in tissue, LB, and BALF of all mice. The decrease in PG16:0/16:0 content was accounted for by increased longer-chain PG species (see supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). Analysis of the “minor components” of surfactant showed alterations in phosphatidylinositol (PI). PI was increased twofold in lung tissue and LB fractions. Notably, content of PI16:0/22:6 increased in the progression from tissue, through LB to BALF. The content of PI16:1/18:1, PI16:0/18:1, PI18:1/18:2, and PI18:1/18:1 was increased in Abca3Δ/Δ compared with control mice at the expense of longer-chain PI species (see supplemental Fig. 2, C–E).

Fig. 6.

Phospholipid composition and synthesis are altered in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Relative distribution of the phospholipid classes PC, phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and phosphatidylinositol (PI) in lung tissue (after lavage), isolated LBs, and BALF from Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates were analyzed by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. There was a reduction in total PC (BALF) and PG (BALF and LB) and an increase in total PI in the Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Synthesis of PC was determined from incorporation of methyl-D9-choline into intact molecular species and expressed as fractional enrichment of labeled substrate relative to total PC. This analysis showed that while the rate of PC synthesis was decreased in lavaged tissue and LBs and despite the lower PC content in BALF, synthesis and secretion of BALF PC from functional type II cells were unaltered in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Sums of individual molecular species from each phospholipid class are expressed as means ± SE of 6–8 animals per group.

Deletion of Abca3 influences genes regulating lipid synthesis and transport in type II epithelial cells.

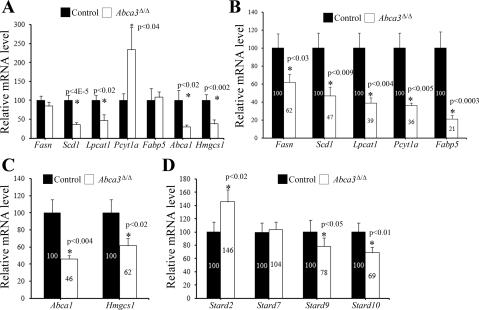

RNA was extracted from whole lung homogenate from E18.5 Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice. RNAs were hybridized to the murine genome MOE430 chip. Data were analyzed using the publically available web-based tool DAVID. RNA microarray analysis of E18.5 Abca3Δ/Δ mice revealed that deletion of Abca3 influenced a number of mRNAs related to lipid metabolism (Table 1). To determine whether deletion of Abca3 in respiratory epithelial cells altered expression of genes regulating lipid homeostasis, expression of mRNAs of genes associated with lipid synthesis and transport was assessed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7A). A marked decrease in mRNAs influencing fatty acid (Scd1 and Lpcat1) and cholesterol (Hmgcs1 and Abca1) metabolism was observed in the lungs of newborn Abca3Δ/Δ mice, perhaps indicating response to altered lipid handling in the absence of ABCA3. In contrast, Pcyt1a mRNA coding for the choline cytidylyltransferase-α (CCTα) protein was upregulated in lungs from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice.

Table 1.

Alterations in gene expression after deletion of Abca3 in type II epithelial cells

| Gene | Reference Sequence ID | Description | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqp3 | 1422008_a_at | Aquaporin 3 | −7.092 |

| Sftpa1 | 1429626_at | Surfactant-associated protein A1 | −3.953 |

| Gjb6 | 1448397_at | Gap junction membrane channel protein-β6 | −3.636 |

| Aqp5 | 1418818_at | Aquaporin 5 | −3.195 |

| Lipg | 1421262_at | Lipase, endothelial | −2.445 |

| Pnliprp1 | 1415777_at | Pancreatic lipase-related protein 1 | −2.155 |

| Lpcat1 | 1424460_at | Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 | −2.114 |

| Rab27a | 1429123_at | Rab27a member RAS oncogene family (GTP-binding) | −1.898 |

| Pnpla2 | 1428591_at | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 2 | −1.587 |

| Sc5d | 1434520_at | Sterol-C5-desaturase homolog | +1.712 |

Differences in mRNAs in the lung of embryonic day 18.5 Abca3Δ/Δ and control mice were identified through microarray analysis. Genes most changed after deletion of Abca3 are shown. Differentially expressed genes were identified using a univariate F test and a permutation test (n = 100) with a significance level of 0.05.

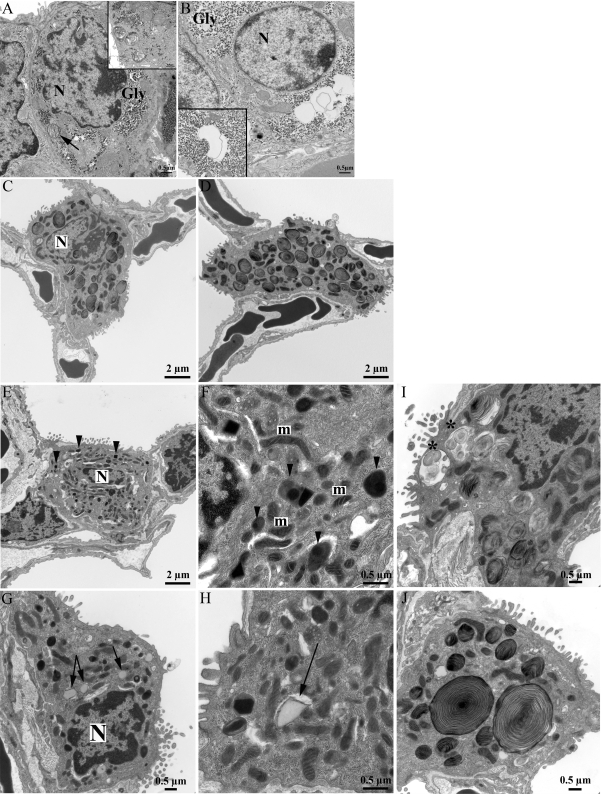

Fig. 7.

Deletion of Abca3 alters expression of mRNAs controlling lipid metabolism in adult type II epithelial cells. mRNAs for selected genes associated with lipid synthesis and transfer were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR in total lung from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ and control littermates (A) and from alveolar type II cells isolated from adult control or Abca3Δ/Δ mice for fatty acid and PC (B; Fasn, Scd1, Lpcat1, Pcyt1a, and Fabp5), cholesterol (C; Abca1 and Hmgcs1), or members of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (Star)-related transfer (START) domain superfamily (D; Stard2, Stard7, Stard9, and Stard10). Results were normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed as means ± SE of 4 animals per group. Scd1, Lpcat1, Abca1, and Hmgcs1 were significantly decreased in lungs from PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control littermates. mRNAs from fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism were significantly decreased in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. While Stard9 and Stard10 were reduced in adult Abca3Δ/Δ type II cells, Stard2 was significantly increased.

Expression of mRNAs of genes associated with lipid synthesis, transport, and secretion in alveolar type II cells isolated from 9-mo-old mice was assessed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7). A marked decrease in mRNAs influencing fatty acid metabolism (Scd1, Fasn, Fabp5, Lpcat1, and Pcyt1a; Fig. 7B) and cholesterol metabolism (Hmgcs1 and Abca1; Fig. 7C) was observed in total type II cells of 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Levels of mRNAs encoding a family of lipid transfer proteins, Stard2, Stard7, Stard9, and Stard10, were assessed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 7D). Stard2 was significantly upregulated in total type II cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control, whereas Stard9 and Stard10 were slightly reduced.

To determine whether the alterations in mRNA expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism are triggered by cell death in response to Abca3 deletion in the respiratory epithelium, apoptosis was assessed by immunohistochemistry using cleaved caspase-3 as a marker. No differences in cleaved caspase-3 staining were observed in lungs of 4-wk-old and 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with control littermates (data not shown), indicating that alveolar type II cell survival was not affected by the deletion of Abca3.

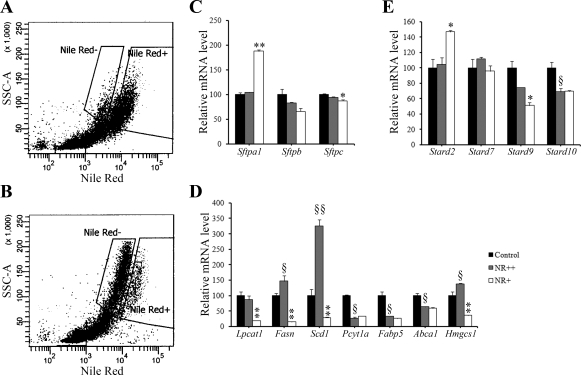

To assess the potential compensatory regulation of gene expression between the two populations of alveolar type II cells in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice, type II cells were isolated from the lung and then distinguished by flow cytofluorometry using NR. Highly enriched populations of NR-positive (NR++) and NR weakly (NR+) stained cells were obtained by excluding from the sort cells in the region of overlap between the two peaks. NR is a fluorescent hydrophobic probe that stains both neutral lipid and phospholipid inclusions using specific filter packages. When cells were subjected to flow cytofluorometric analysis under red fluorescence conditions (>630 nm), two cell populations stained with NR were observed in Abca3Δ/Δ mice; only one cell population (NR++) was present in control mice. In Abca3Δ/Δ mice, the phospholipid-loaded (NR++) cells (undeleted Abca3 cells) were differentiated by stronger fluorescence intensity, which was similar to findings in Abca3flx/flx cells in control mice. Abca3Δ/Δ cells displayed weaker fluorescence (NR+; Fig. 8A), because these cells lack LBs and NR is taken up by cell membrane lipids as well as by intracellular lipid droplets. Expression of mRNAs of genes associated with surfactant, lipid synthesis, transport, and secretion was assessed by qRT-PCR in NR++ and NR+ type II cells. Sftpa1 was significantly increased in NR+ compared with NR++ and control type II cells. A marked decrease in mRNAs influencing fatty acid (Scd1, Fasn, and Lpcat1) and cholesterol (Hmgcs1; Fig. 8C) metabolism was observed in NR+ type II cells isolated from 9-mo-old Abca3Δ/Δ mice compared with NR++ type II cells, supporting a decrease in the activity of surfactant synthesis pathways in the targeted cells. In contrast, Fasn, Scd1, and Hmgcs1 mRNA expression was increased in NR++ cells compared with control type II cells, perhaps indicating a selective compensatory lipid synthesis pathway in ABCA3-sufficient cells. On the other hand, mRNA expression of other genes (Sftpb, Pcyt1a, Fabp5, and Abca1) was similarly decreased in NR+ and NR++ type II cells, indicating that compensatory mechanisms were partial in response to deletion of Abca3. Finally, Stard2 was significantly increased in Abca3-deficient cells compared with Abca3-sufficient cells, whereas Stard9 was slightly reduced (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

Deletion of Abca3 induces compensatory mechanisms in both type II cell populations present in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Flow cytofluorometric data of alveolar type II cells from adult control (A) and Abca3Δ/Δ (B) mice stained with Nile red (NR) showed 1 cell population with high fluorescence intensity (NR++) and 1 cell population with lower fluorescence intensity (NR+). mRNAs were extracted from alveolar type II cells isolated from adult control or Abca3Δ/Δ mice and sorted according to NR fluorescence intensity. SSC-A, side-scatter area. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to estimate gene mRNA levels for surfactant-associated proteins (C; Sftpa1, Sftpb, and Sftpc), lipid metabolism (D; Fasn, Scd1, Lpcat1, Pcyt1a, Fabp5, Abca1, and Hmgcs1), or members of the START domain superfamily (E; Stard2, Stard7, Stard9, and Stard10). Sftpa1 and Stard2 were significantly increased in NR+ cells compared with control and NR++ cells. Fasn, Scd1, Lpcat1, Pcyt1a, and Hmgcs1 were significantly reduced in NR+ cells compared with control and NR++ cells. Fasn, Scd1 and Hmgcs1 were significantly increased in NR++ cells compared with control cells. Results were normalized to 18S rRNA and are representative of 4 animals per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. NR++ cells. §P < 0.05 and §§P < 0.01 vs. control cells.

Deletion of Abca3 alters the transcriptional network associated with lipid homeostasis in alveolar type II cells.

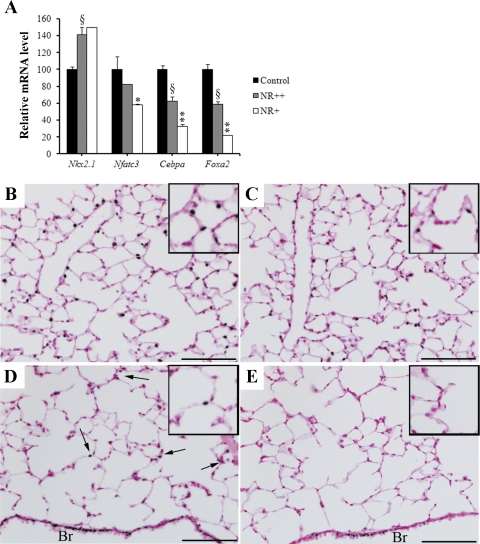

Nfatc3, Cebpa, and Foxa2 mRNAs, genes known to influence expression of genes regulating surfactant lipid homeostasis, were significantly reduced in NR+ type II cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 9A). Nkx2.1 mRNA was similar in NR++ and NR+ cells. Immunostaining for FOXA2 was readily detected in type II cells in control mice (Fig. 9, B and C). In contrast, numbers and intensity of FOXA2 staining of type II cells were decreased in Abca3Δ/Δ mice (Fig. 9, D and E).

Fig. 9.

Deletion of Abca3 influences the transcriptional program in alveolar type II cells. A: mRNAs were extracted from alveolar type II cells isolated from adult control or Abca3Δ/Δ mice and sorted according to NR fluorescence intensity. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to estimate gene mRNA levels for transcription factors known to play a critical role in lung homeostasis (Nkx2.1, Nfatc3, Foxa2, and Cebpa). Results were normalized to 18S rRNA. Nfatc3, Foxa2, and Cebpa mRNAs were significantly reduced in NR+ cells compared with control and NR++ cells. Foxa2 and Cebpa mRNAs were significantly decreased in NR++ cells compared with control cells. In contrast, Nkx2.1 was significantly increased in NR++ and NR+ cells compared with control cells. Results are representative of 4 animals per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. NR++ cells. §P < 0.05 vs. control cells. Lung tissue from adult control (B and C) and Abca3Δ/Δ (D and E) mice was immunostained for FOXA2 at 1:4,000 (B and D) and 1:8,000 (C and E) dilutions. FOXA2 was detected in control lungs at both dilutions (B and C). In Abca3Δ/Δ mice, while FOXA2 was detected in the bronchiolar epithelium (Br) at both dilutions, FOXA2 was detected in few type II cells (arrows) at 1:4,000 (D) and absent at 1: 8,000 (E). Scale bars, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

Abca3, a lipid transporter protein that is highly expressed in the lung alveolar type II cells (32, 52, 55), is critical for surfactant lipid homeostasis and for adaptation to air breathing. Germ-line deletion of the mouse Abca3 gene caused respiratory distress immediately followed by death at birth (2, 13, 19, 23), and severe mutations in ABCA3 caused respiratory failure in newborn infants (42). Since chronic lung disease was reported in older patients (11, 17), we used a conditional system to selectively delete Abca3 in alveolar epithelial cells of the mouse lung to assess the long-term effect of Abca3 deficiency in the lung.

In the present work, respiratory epithelium-specific, conditional deletion of Abca3 caused respiratory distress and death, confirming previous findings that Abca3 was critical for adaptation for air breathing (2, 13, 19, 23). In mice that died at birth, Abca3 mRNA was reduced by 85–90% and was associated with the absence of LBs in type II epithelial cells. Thickened mesenchyme and glycogen accumulation in Abca3Δ/Δ type II cells were consistent with immaturity of the alveolar epithelium, indicating that Abca3 participates in lung maturation. Levels of SP-B and proSP-C, which are important for surfactant homeostasis, were not altered in newborn Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Surviving Abca3Δ/Δ mice developed emphysema, in contrast to previous models, in which lungs of Abca3+/− mice were normal in adulthood (13, 19). ABCA3-deficient and -sufficient cells were identified in the present model. While ABCA3 was decreased by 50% in each type II cell in Abca3+/− mice, lungs of Abca3Δ/Δ mice contained two subpopulations of type II cells: those expressing ABCA3 and those not expressing ABCA3. Thus Abca3Δ/Δ mice represent a model wherein the alveolar epithelium is variably affected, a model that is perhaps consistent with lung injury or infection, in which Abca3 gene expression is altered regionally. The present model indicates that ABCA3-sufficient type II cells compensate for the loss of ABCA3 in other cells to maintain surfactant production. Abca3Δ/Δ mice developed emphysema, perhaps indicating that ABCA3 deficiency resulted in cell injury and lung remodeling. Although the majority of mutations in ABCA3 are associated with neonatal lethality, a few ABCA3 mutations are associated with interstitial lung disease in older children who survive beyond the perinatal period (12, 17, 54). The heterozygosity for an ABCA3 mutation was associated with a more severe clinical presentation in the case of a SFTPC mutation, indicating the importance of ABCA3 in alveolar homeostasis that may influence the pathogenesis of lung disease (10).

Expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism was decreased during the perinatal period as well as in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Expression of genes dedicated to the biosynthesis of fatty acids and phospholipids was decreased, consistent with altered lipid content in the lungs of newborn Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Decreased expression of mRNAs related to lipid metabolism [acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acoxl), Lpcat1, Sftpa1, lipase (Lipg), glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain-containing protein 2 (Gdpd2), pancreatic lipase-related protein 1 (Pnliprp1), delta-like 1 (Dlk1), and patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 2 (Pnpla2)] was observed at E18.5. Such changes in gene expression may represent an indirect effect of ABCA3 deficiency and alteration in cellular lipids or, alternatively, a generalized delay in type II cell maturation. Gene Ontology and network analysis on mRNAs that were altered >1.5-fold suggested “lipid/sterol metabolism” as a major group of associated genes influenced by Abca3 deletion. Expression of genes regulating lipid synthesis (Lpcat1, Scd1, Abca1, and Hmgcs1) was decreased at PND0 in Abca3Δ/Δ mice, consistent with the RNA microarray data. In contrast, Pcyt1a was increased in PND0 Abca3Δ/Δ lungs, perhaps indicating a compensatory role for CCTα in PC synthesis after birth. Lung epithelial cell-specific deletion of Pcyt1a resulted in severe respiratory failure at birth due to a major defect in phospholipid synthesis and LB formation (45). In the adult Abca3Δ/Δ type II cells, decreased expression of several genes, including Scd1, Fasn, Lpcat1, and Pcyt1a, as well as Hmgcs1 (a gene critical for cholesterol synthesis), also was observed, demonstrating that chronic deletion of Abca3 altered lipid biosynthesis in type II epithelial cells after birth. Expression of a number of lipid transporters, including the fatty acid-binding protein 5 (Fabp5) and cholesterol transporter ATP-binding cassette A1 (Abca1), was decreased in type II cells of Abca3Δ/Δ mice. For most of these genes, levels of mRNA were reduced by 40–70%, consistent with the loss of ABCA3 in 50% of type II cells in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. This inhibition of lipid biosynthesis and transport may serve to counterregulate surfactant production, since it can no longer be packaged and secreted properly in the alveolar space. Alternatively, cell injury related to the lack of ABCA3 may initiate an inhibitory effect on lipid biosynthesis. While Sftpa1 mRNA was decreased in newborn Abca3Δ/Δ lungs, it was increased in ABCA3-deficient type II cells in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice, perhaps indicating a compensatory role for SFTPA1 in the formation of tubular myelin in the ABCA3-deficient cells.

Lungs of surviving Abca3Δ/Δ mice contained two distinct populations of alveolar type II cells: one lacking LBs and the other containing LBs of various size. Absence of LBs related to the deletion of Abca3 in type II cells was consistent with previous mouse and human studies (2, 13, 19, 20, 23, 42). The presence of large atypical LBs and ABCA3 protein in a subset of type II cells indicates both targeting and compensatory responses to the lack of surfactant synthesis in coexisting Abca3 targeted cells, a concept supported by analysis of Abca3 mRNA levels and ABCA3 expression by immunohistochemistry. Mouse Abca3Δ/Δ cells lacking LBs contained structures of intermediate electron density with electron-dense inclusions scattered throughout the cytoplasm of type II cells, similar to findings in patients with ABCA3 mutations (11, 18, 40, 42, 43). Abca3Δ/Δ cells lacking LBs were enriched in atypical lipid vesicles that appear to contain neutral lipids based on their staining characteristics. In contrast, alveolar type II cells wherein deletion of Abca3 did not occur contained heterogeneous populations of LBs, some of which were enlarged. The abnormal accumulation of LBs may indicate the existence of a compensatory pathway that serves to enhance surfactant production. Fasn, Scd1, and Hmgcs1 mRNAs were increased in type II cells from Abca3Δ/Δ mice, wherein deletion of Abca3 did not occur, providing further support for the concept of a compensatory pathway maintaining surfactant synthesis. It is unclear whether the lack of ABCA3 in a subset of cells or compensatory changes in ABCA3-sufficient cells influences cell injury and leads to emphysema in the Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Nonuniform exogenous expression of SFTPB in distal respiratory epithelial type II cells of Sftpb−/− mice, resulting in the presence of both SFTPB-deficient and -sufficient cells, was associated with air space enlargement and alterations in LB structure, phenotype similar to the adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice (33). These data suggest that focal variations of surfactant production and secretion may be responsible for alterations in lung structure and function and that they may be partially corrected by SFTPB- or ABCA3-sufficient cells.

Deletion of Abca3 altered Sat PC levels and phospholipid composition in newborn and adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice. The decreased PC and PG content in newborn Abca3Δ/Δ lungs is consistent with previous reports in Abca3−/− mice (2, 13, 19). PC and PG contribute to surfactant function, and thus their dramatic reduction in newborn Abca3−/− mice is likely directly correlated with respiratory distress and death at birth. Our results and other studies demonstrate that deletion of Abca3 in alveolar type II cells from newborn mice reduces surfactant PC, especially short acyl chain species, which are important for maintaining normal lung function (4, 36). In the surviving Abca3Δ/Δ mice, while PC was significantly reduced in BALF, no differences were observed in the lung tissue (after lavage) and LB fractions, perhaps indicating differences in secretion or recycling. In agreement with the morphological analysis, two metabolically distinct LB populations could be distinguished in the adult Abca3Δ/Δ mouse lung. The methyl-D9-choline incorporation data suggest that one subset of Abca3Δ/Δ mouse lung LBs accumulates and secretes PC at a rate similar to that of control mice. The second subset of LBs contains a more metabolically inert pool of PC that is not secreted. The lower PC content of BALF in adult Abca3Δ/Δ mice would then be a direct consequence of fewer type II cells containing functional LBs. While methyl-D9-choline incorporation data might suggest a defect in surfactant secretion in Abca3Δ/Δ mice, the similarity of fractional incorporation of label into BALF PC in the two groups of animals indicates little change in the kinetics of surfactant PC secretion from functional type II cells in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. PG was markedly reduced in LB and BALF fractions, but not in the lung tissue, indicating that PG transport and packaging in LBs and secretion are altered after deletion of Abca3. Analysis of the minor surfactant phospholipids demonstrated significant increases in PI (lung tissue after lavage and LBs) in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Similar alterations in PC, PG, and PI were shown in “at-risk” or acute respiratory distress syndrome patients (22). Whether ABCA3 deficiency enhances susceptibility to lung injury is unclear. Adult Stat3Δ/Δ mice, in which levels of Abca3 mRNA and protein and lung Sat PC are reduced, are susceptible to lung injury induced by hyperoxia (31).

Stard2 mRNA was increased in ABCA3-deficient type II cells. The steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)-related lipid transfer (START) domain proteins bind lipids (1). The START domain is thought to be a lipid-exchange and/or a lipid sensing domain that mediates lipid transfer between intracellular compartments. PC and PE are known ligands for STARD2 and STARD10. STARD2 may play a role in the maintenance of lipid homeostasis in Abca3Δ/Δ mice. Since START domain proteins frequently contain homeodomains, they may function as lipid-responsive transcription factors or coactivators (41). Kanno et al. (27) showed that STARD2 coactivates transcriptional activity of paired box protein (PAX3) in vitro, providing a potential mechanism by which lipid metabolism is linked to transcriptional programs.

Previous studies established that NKX2.1 (15), FOXA2 (47, 48), C/EBPα (30), and NFATc3 (14) are critical for perinatal lung function, directly regulating surfactant protein, and influencing surfactant lipid synthesis. Comparison of lung mRNAs from CebpaΔ/Δ (30), Cnb1Δ/Δ (14), Foxa2Δ/Δ (47), and Titf1PM/PM mice (15) demonstrated that a number of mRNAs were similarly influenced in each model. Genes involved in the regulation of lung lipid homeostasis were decreased after deletion or mutation of each of these transcription factors. In the present study, Foxa2 and Cebpa mRNAs were markedly reduced in Abca3Δ/Δ type II cells, suggesting their potential role in the downregulation of genes regulating lung lipid homeostasis. Susceptibility of adult CebpaΔ/Δ mice to lung injury induced by hyperoxia was associated with the decrease of genes regulating surfactant lipid homeostasis and surfactant protein biosynthesis, processing, and transport (51). Mechanisms by which ABCA3 deficiency influences transcriptional pathways to modulate lipid homeostasis in type II cells remain unknown.

The present study demonstrates that Abca3 is required not only for respiration at birth, but also for maintaining lung phospholipid homeostasis after birth, influencing lipid biosynthesis and trafficking. Present findings support the presence of a sensing pathway within and between ABCA3-sufficient and -deficient alveolar type II cells that initiates compensation at transcriptional and metabolic levels. Maintenance of respiratory function, despite alterations in lipid synthesis and secretion by a subset of Abca3 gene-deleted type II epithelial cells, indicates compensatory mechanisms by which type II cells maintain surfactant lipid homeostasis in the alveolar epithelium. Alterations of ABCA3 expression may render individuals, newborns, infants, and older individuals more susceptible to acute and chronic lung diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-38859 (J. A. Whitsett).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpy F, Tomasetto C. Give lipids a START: the StAR-related lipid transfer (START) domain in mammals. J Cell Sci 118: 2791–2801, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ban N, Matsumura Y, Sakai H, Takanezawa Y, Sasaki M, Arai H, Inagaki N. ABCA3 as a lipid transporter in pulmonary surfactant biogenesis. J Biol Chem 282: 9628–9634, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem 234: 466–468, 1959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernhard W, Haslam PL, Floros J. From birds to humans: new concepts on airways relative to alveolar surfactant. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30: 6–11, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernhard W, Pynn CJ, Jaworski A, Rau GA, Hohlfeld JM, Freihorst J, Poets CF, Stoll D, Postle AD. Mass spectrometric analysis of surfactant metabolism in human volunteers using deuteriated choline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 54–58, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besnard V, Wert SE, Stahlman MT, Postle AD, Xu Y, Ikegami M, Whitsett JA. Deletion of Scap in alveolar type II cells influences lung lipid homeostasis and identifies a compensatory role for pulmonary lipofibroblasts. J Biol Chem 284: 4018–4030, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Besnard V, Xu Y, Whitsett JA. Sterol response element binding protein and thyroid transcription factor-1 (Nkx2.1) regulate Abca3 gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1395–L1405, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 37: 911–917, 1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown WJ, Sullivan TR, Greenspan P. Nile red staining of lysosomal phospholipid inclusions. Histochemistry 97: 349–354, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullard JE, Nogee LM. Heterozygosity for ABCA3 mutations modifies the severity of lung disease associated with a surfactant protein C gene (SFTPC) mutation. Pediatr Res 62: 176–179, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bullard JE, Wert SE, Nogee LM. ABCA3 deficiency: neonatal respiratory failure and interstitial lung disease. Semin Perinatol 30: 327–334, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullard JE, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M, Nogee LM. ABCA3 mutations associated with pediatric interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 1026–1031, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheong N, Zhang H, Madesh M, Zhao M, Yu K, Dodia C, Fisher AB, Savani RC, Shuman H. ABCA3 is critical for lamellar body biogenesis in vivo. J Biol Chem 282: 23811–23817, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dave V, Childs T, Xu Y, Ikegami M, Besnard V, Maeda Y, Wert SE, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR, Whitsett JA. Calcineurin/Nfat signaling is required for perinatal lung maturation and function. J Clin Invest 116: 2597–2609, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeFelice M, Silberschmidt D, DiLauro R, Xu Y, Wert SE, Weaver TE, Bachurski CJ, Clark JC, Whitsett JA. TTF-1 phosphorylation is required for peripheral lung morphogenesis, perinatal survival, and tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem 278: 35574–35583, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol 4: P3, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doan ML, Guillerman RP, Dishop MK, Nogee LM, Langston C, Mallory GB, Sockrider MM, Fan LL. Clinical, radiological and pathological features of ABCA3 mutations in children. Thorax 63: 366–373, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards V, Cutz E, Viero S, Moore AM, Nogee L. Ultrastructure of lamellar bodies in congenital surfactant deficiency. Ultrastruct Pathol 29: 503–509, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzgerald ML, Xavier R, Haley KJ, Welti R, Goss JL, Brown CE, Zhuang DZ, Bell SA, Lu N, McKee M, Seed B, Freeman MW. ABCA3 inactivation in mice causes respiratory failure, loss of pulmonary surfactant, and depletion of lung phosphatidylglycerol. J Lipid Res 48: 621–632, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garmany TH, Moxley MA, White FV, Dean M, Hull WM, Whitsett JA, Nogee LM, Hamvas A. Surfactant composition and function in patients with ABCA3 mutations. Pediatr Res 59: 801–805, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenspan P, Fowler SD. Spectrofluorometric studies of the lipid probe, Nile red. J Lipid Res 26: 781–789, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory TJ, Longmore WJ, Moxley MA, Whitsett JA, Reed CR, Fowler AA, 3rd, Hudson LD, Maunder RJ, Crim C, Hyers TM. Surfactant chemical composition and biophysical activity in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest 88: 1976–1981, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammel M, Michel G, Hoefer C, Klaften M, Muller-Hocker J, de Angelis MH, Holzinger A. Targeted inactivation of the murine Abca3 gene leads to respiratory failure in newborns with defective lamellar bodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359: 947–951, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res 31: e15, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4: 249–264, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jobe A, Kirkpatrick E, Gluck L. Labeling of phospholipids in the surfactant and subcellular fractions of rabbit lung. J Biol Chem 253: 3810–3816, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanno K, Wu MK, Agate DS, Fanelli BJ, Wagle N, Scapa EF, Ukomadu C, Cohen DE. Interacting proteins dictate function of the minimal START domain phosphatidylcholine transfer protein/StarD2. J Biol Chem 282: 30728–30736, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin S, Phillips KS, Wilder MR, Weaver TE. Structural requirements for intracellular transport of pulmonary surfactant protein B (SP-B). Biochim Biophys Acta 1312: 177–185, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Morrisey EE, Whitsett JA. GATA-6 is required for maturation of the lung in late gestation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L468–L475, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martis PC, Whitsett JA, Xu Y, Perl AK, Wan H, Ikegami M. C/EBPα is required for lung maturation at birth. Development 133: 1155–1164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuzaki Y, Besnard V, Clark JC, Xu Y, Wert SE, Ikegami M, Whitsett JA. STAT3 regulates ABCA3 expression and influences lamellar body formation in alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38: 551–558, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulugeta S, Gray JM, Notarfrancesco KL, Gonzales LW, Koval M, Feinstein SI, Ballard PL, Fisher AB, Shuman H. Identification of LBM180, a lamellar body limiting membrane protein of alveolar type II cells, as the ABC transporter protein ABCA3. J Biol Chem 277: 22147–22155, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesslein LL, Melton KR, Ikegami M, Na CL, Wert SE, Rice WR, Whitsett JA, Weaver TE. Partial SP-B deficiency perturbs lung function and causes air space abnormalities. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L1154–L1161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perl AK, Wert SE, Nagy A, Lobe CG, Whitsett JA. Early restriction of peripheral and proximal cell lineages during formation of the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10482–10487, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perl AK, Zhang L, Whitsett JA. Conditional expression of genes in the respiratory epithelium in transgenic mice: cautionary notes and toward building a better mouse trap. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40: 1–3, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Postle AD, Gonzales LW, Bernhard W, Clark GT, Godinez MH, Godinez RI, Ballard PL. Lipidomics of cellular and secreted phospholipids from differentiated human fetal type II alveolar epithelial cells. J Lipid Res 47: 1322–1331, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Postle AD, Heeley EL, Wilton DC. A comparison of the molecular species compositions of mammalian lung surfactant phospholipids. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 129: 65–73, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice WR, Conkright JJ, Na CL, Ikegami M, Shannon JM, Weaver TE. Maintenance of the mouse type II cell phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 283: L256–L264, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sauer B. Inducible gene targeting in mice using the Cre/lox system. Methods 14: 381–392, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saugstad OD, Hansen TW, Ronnestad A, Nakstad B, Tollofsrud PA, Reinholt F, Hamvas A, Coles FS, Dean M, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Nogee LM. Novel mutations in the gene encoding ATP binding cassette protein member A3 (ABCA3) resulting in fatal neonatal lung disease. Acta Paediatr 96: 185–190, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrick K, Nguyen D, Karlowski WM, Mayer KF. START lipid/sterol-binding domains are amplified in plants and are predominantly associated with homeodomain transcription factors. Genome Biol 5: R41, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shulenin S, Nogee LM, Annilo T, Wert SE, Whitsett JA, Dean M. ABCA3 gene mutations in newborns with fatal surfactant deficiency. N Engl J Med 350: 1296–1303, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Somaschini M, Nogee LM, Sassi I, Danhaive O, Presi S, Boldrini R, Montrasio C, Ferrari M, Wert SE, Carrera P. Unexplained neonatal respiratory distress due to congenital surfactant deficiency. J Pediatr 150: 649–653, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stahlman MT, Besnard V, Wert SE, Weaver TE, Dingle S, Xu Y, von Zychlin K, Olson SJ, Whitsett JA. Expression of ABCA3 in developing lung and other tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 55: 71–83, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian Y, Zhou R, Rehg JE, Jackowski S. Role of phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-α in lung development. Mol Cell Biol 27: 975–982, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vorbroker DK, Profitt SA, Nogee LM, Whitsett JA. Aberrant processing of surfactant protein C in hereditary SP-B deficiency. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 268: L647–L656, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan H, Dingle S, Xu Y, Besnard V, Kaestner KH, Ang SL, Wert S, Stahlman MT, Whitsett JA. Compensatory roles of Foxa1 and Foxa2 during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem 280: 13809–13816, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wan H, Xu Y, Ikegami M, Stahlman MT, Kaestner KH, Ang SL, Whitsett JA. Foxa2 is required for transition to air breathing at birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14449–14454, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wert SE, Glasser SW, Korfhagen TR, Whitsett JA. Transcriptional elements from the human SP-C gene direct expression in the primordial respiratory epithelium of transgenic mice. Dev Biol 156: 426–443, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wert SE, Yoshida M, LeVine AM, Ikegami M, Jones T, Ross GF, Fisher JH, Korfhagen TR, Whitsett JA. Increased metalloproteinase activity, oxidant production, and emphysema in surfactant protein D gene-inactivated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5972–5977, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu Y, Saegusa C, Schehr A, Grant S, Whitsett JA, Ikegami M. C/EBPα is required for pulmonary cytoprotection during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L286–L298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamano G, Funahashi H, Kawanami O, Zhao LX, Ban N, Uchida Y, Morohoshi T, Ogawa J, Shioda S, Inagaki N. ABCA3 is a lamellar body membrane protein in human lung alveolar type II cells. FEBS Lett 508: 221–225, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida I, Ban N, Inagaki N. Expression of ABCA3, a causative gene for fatal surfactant deficiency, is up-regulated by glucocorticoids in lung alveolar type II cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323: 547–555, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young LR, Nogee LM, Barnett B, Panos RJ, Colby TV, Deutsch GH. Usual interstitial pneumonia in an adolescent with ABCA3 mutations. Chest 134: 192–195, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zen K, Notarfrancesco K, Oorschot V, Slot JW, Fisher AB, Shuman H. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies to alveolar type II cell lamellar body membrane. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L172–L183, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou L, Dey CR, Wert SE, Yan C, Costa RH, Whitsett JA. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-3β limits cellular diversity in the developing respiratory epithelium and alters lung morphogenesis in vivo. Dev Dyn 210: 305–314, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.