Abstract

Mice with smooth muscle (SM)-specific knockout of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 (NCX1SM−/−) and the NCX inhibitor, SEA0400, were used to study the physiological role of NCX1 in mouse mesenteric arteries. NCX1 protein expression was greatly reduced in arteries from NCX1SM−/− mice generated with Cre recombinase. Mean blood pressure (BP) was 6–10 mmHg lower in NCX1SM−/− mice than in wild-type (WT) controls. Vasoconstriction was studied in isolated, pressurized mesenteric small arteries from WT and NCX1SM−/− mice and in heterozygotes with a global null mutation (NCX1Fx/−). Reduced NCX1 activity was manifested by a marked attenuation of responses to low extracellular Na+ concentration, nanomolar ouabain, and SEA0400. Myogenic tone (MT, 70 mmHg) was reduced by ∼15% in NCX1SM−/− arteries and, to a similar extent, by SEA0400 in WT arteries. MT was normal in arteries from NCX1Fx/− mice, which had normal BP. Vasoconstrictions to phenylephrine and elevated extracellular K+ concentration were significantly reduced in NCX1SM−/− arteries. Because a high extracellular K+ concentration-induced vasoconstriction involves the activation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (LVGCs), we measured LVGC-mediated currents and Ca2+ sparklets in isolated mesenteric artery myocytes. Both the currents and the sparklets were significantly reduced in NCX1SM−/− (vs. WT or NCX1Fx/−) myocytes, but the voltage-dependent inactivation of LVGCs was not augmented. An acute application of SEA0400 in WT myocytes had no effect on LVGC current. The LVGC agonist, Bay K 8644, eliminated the differences in LVGC currents and Ca2+ sparklets between NCX1SM−/− and control myocytes, suggesting that LVGC expression was normal in NCX1SM−/− myocytes. Bay K 8644 did not, however, eliminate the difference in myogenic constriction between WT and NCX1SM−/− arteries. We conclude that, under physiological conditions, NCX1-mediated Ca2+ entry contributes significantly to the maintenance of MT. In NCX1SM−/− mouse artery myocytes, the reduced Ca2+ entry via NCX1 may lower cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and thereby reduce MT and BP. The reduced LVGC activity may be the consequence of a low cytosolic Ca2+ concentration.

Keywords: mesenteric arteries, myogenic tone, patch clamp, calcium sparklets, Bay K 8644

the sodium/calcium exchanger (NCX), which can mediate both Ca2+ exit and Ca2+ entry in cells (5), has been postulated to play a central role in arterial smooth muscle (SM) cell (ASMC) Ca2+ handling and in the maintenance of arterial tone and blood pressure (BP) (4). The block of NCX by the specific inhibitor, SEA0400 (25), in small arteries preconstricted with a low-dose ouabain lowers the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]Cyt) and induces vasodilation (21, 48). Moreover, the SM-specific overexpression of NCX elevates BP and induces salt-dependent hypertension, and SEA0400 lowers BP in several salt-dependent animal models (21). Indeed, NCX type-1 (NCX1) is upregulated in mesenteric arteries from rats with ouabain-induced hypertension (33) and pulmonary arteries from humans with primary pulmonary hypertension (49). Whether NCX is involved in maintaining normal BP, however, has not been resolved. Here we employ a SM-specific knockout approach to examine the role of NCX in arterial contractility and the maintenance of vascular tone and BP.

Three isoforms of NCX have been identified: NCX1 is abundant in the heart and is ubiquitously expressed, whereas NCX2 and NCX3 are both restricted to brain and skeletal muscle (34). NCX1 is the only isoform present in ASMCs, where two splice variants, NCX1.3 and NCX1.7, are expressed (27, 35). In cardiac myocytes, NCX1 makes a major contribution to Ca2+ extrusion during diastole (3, 11). Nevertheless, cardiac-specific NCX1 knockout mice thrive: the loss of NCX1 is compensated by a reduced L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (LVGC) current and a shortened action potential because of accelerated Ca2+-dependent LVGC inactivation and augmented transient outward K+ current (18, 31, 32). Importantly, cardiac NCX1-mediated Ca2+ flux must be inward during depolarization and systole (5). The situation is complicated, however, because exchanger-mediated fluxes depend on the relative activation of the exchanger, governed by cytosolic Na+ and Ca2+ (26), as well as on the net driving force, governed by the membrane potential (Vm) and the Na+ and Ca2+ electrochemical gradients (5).

ASMC NCX1, too, can play an important role in Ca2+ extrusion when [Ca2+]Cyt is suddenly elevated (23, 40, 41). Nevertheless, under near steady-state conditions, when ASMC activation and the Vm are both relatively constant, NCX1 should tend to operate close to its reversal potential (ENa/Ca). This is determined by the Na+ and Ca2+ electrochemical potentials, ENa and ECa, respectively, and the 3 Na+:1 Ca2+-coupling ratio: i.e., ENa/Ca = 3ENa − 2ECa (5). The driving force on Ca2+ (Vm − ENa/Ca) is governed by changes in Vm and cytosolic Na+ and Ca2+. The exchanger can move (net) Ca+ either outward when (Vm − ENa/Ca) is negative or inward when (Vm − ENa/Ca) is positive.

The inhibitory effects of SEA0400 on [Ca2+]Cyt and myogenic tone (MT) suggested that NCX1 mediates (net) Ca2+ entry in ASMCs within pressurized, tonically constricted small arteries (21, 36, 48). The present report shows that MT is also reduced, as is BP, in SM-specific knockout of NCX1 (NCX1SM−/−) mice. This is consistent with the view (21) that NCX1 normally mediates Ca2+ entry in tonically constricted small arteries. Reduced ASMC NCX1 expression is, however, as in heart (32), accompanied by a functional reduction in Ca2+ entry via LVGCs. The latter is normally a major contributor to MT (8, 20, 47). But, in contrast to cardiac muscle where elevated [Ca2+]Cyt in cardiac muscle-specific NCX1 knockout mice accelerates LVGC inactivation, the reduced MT and low BP suggest that [Ca2+]Cyt may be low in NCX1SM−/− mice. This could explain the reduced protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of LVGCs and, thus, reduced LVGC activation in ASMCs (37).

METHODS

Experimental Animals

Ethical approval.

All mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Generation of NCXSM−/− mice.

NCXSM−/− mice were generated by crossing homozygous NCX1 LoxP [floxed (Fx)] mice (NCX1Fx/Fx) (18) with hemizygous SM-specific Cre recombinase mice (CreSM+) (46). These genetically altered mice are on a C57BL/6J background [denoted as wild-type (WT)] and are congenic with their littermates. The NCX1 exon 11 in NCX1Fx/Fx mice is flanked by two LoxP sites (Fig. 1A) (18). CreSM+ mice were generated by inserting the Cre gene, under the control of the SM myosin heavy chain (MHC) promoter, randomly into the mouse genome. This construct also contained an internal ribosomal entry site and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) downstream from the Cre recombinase (Fig. 1A) to enable simultaneous transcription, but independent translation, of these genes. When the SM-MHC promoter is activated in SM cells, both Cre and eGFP are expressed; the GFP can be visualized by its fluorescence. In these myocytes, Cre excises the genomic exon 11 DNA between the LoxP sites, leaving one intact LoxP site and the gene for a truncated, nonfunctional NCX1.

Fig. 1.

Generation and detection of smooth muscle (SM)-specific Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 (NCX1) knockout (NCX1SM−/−) mice. A: The SM-specific Cre recombinase gene (SM-Cre) contains an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the SM-myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) promoter (top). This gene is randomly inserted into the genome of mice in which exon 11 of the NCX1 genomic sequence is replaced with a floxed exon 11 (middle). When Cre is expressed, the sequence between the LoxP sites, exon 11, is removed leaving 1 innocuous LoxP site (bottom). When the gene is activated, a nonfunctional, truncated NCX1 protein is synthesized and degraded. B: amplification of the wild-type (WT, +), floxed (Fx), and deleted (Del) alleles. PCR primers were designed to anneal to the genomic sequence flanking the LoxP sites indicated in A. These primers amplify all possible combinations of alleles as indicated by the genotypes at the tops of the lanes. C: myocytes are visualized by the GFP fluorescence in the myocytes of a cannulated, pressurized mesenteric small artery; some myocytes do not exhibit GFP fluorescence (white asterisk). D: NCX1 protein expression detected by immunoblot in aorta, heart, mesenteric artery, and urinary bladder from WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice; glutaraldehyde-3-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or β-actin was used as a housekeeping protein, as indicated.

When Cre is expressed in a tissue-specific manner in mice that are homozygous for a floxed gene, both copies of the gene should, theoretically, be excised from the genome only in the target cells to generate a tissue-specific knockout mouse. Although the SM-MHC promoter restricts the adult expression to SM (46), it is also active transiently during male gametogenesis (9, 10, 16), resulting in the recombination of NCX1 exon 11 in meiotic cells. Thus crosses of female NCX1Fx/Fx mice with male NCX1Fx/+-CreSM+ mice (i.e., floxed heterozygotes with a SM-specific Cre gene) produced either NCX1Fx/− (-Cre−) or NCX1Fx/−-CreSM+ (=NCX1SM−/−) mice. The latter contain one globally deleted allele and one SM-specific-deleted allele; i.e., they were SM-specific NCX1 knockout mice. Controls for NCX1SM−/− mice were NCX1Fx/− littermates as well as C57BL/6J WT mice. Genomic DNA, obtained from tail biopsies, was used for genotyping by PCR. Primers for the floxed exon 11 were designed to distinguish the WT, floxed, and deleted alleles (Fig. 1B).

BP Measurements

Telemetric BP measurement.

WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice (∼16 wk old) were anesthetized with isoflurane supplemented with 100% O2. The right common carotid artery was exposed and ligated via an anterior neck midline incision. Telemetric BP sensors (DSI TA11PA-C10, Data Science International, Minneapolis, MN) were used. The catheter of the BP sensor was inserted into a small hole proximal to the ligature, the tip was passed to the origin of the carotid at the aortic arch, and the catheter was fixed in place with a suture and the hole sealed with adhesive (Vetbond, 3M, St. Paul, MN). The body of the sensor was passed through a subcutaneous tunnel to a subcutaneous pocket in the abdominal wall. Following 7–10 days of recovery from surgery, 24-h BPs were recorded with DSI receivers and software.

Intrafemoral BP measurement.

WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice (∼18 wk old) were anesthetized with isoflurane supplemented with 100% O2; the core temperature was maintained at 37.5–38°C. The right femoral artery was surgically isolated and cannulated with a 1.4-Fr Mikro-tip pressure catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX). BP was measured under 1.5% isoflurane anesthesia (22); data were calculated off-line (BioPac System, Santa Barbara, CA). After the experiment, the animal was deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation.

The data collection for both BP methods was performed double blinded: the individual measuring the BP did not know the genotype. Animal code numbers were matched with genotype and BP after the data on all the mice had been collected.

Arterial Diameter and [Ca2+]Cyt and GFP Measurements

Arterial diameter, myogenic reactivity and tone, and evoked vasoconstriction.

WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice (12–16 wk of age) were euthanized with a CO2 overdose followed by cervical dislocation. Small arteries from the superior mesenteric artery arcade were isolated and cannulated at both ends. Arterial diameter, myogenic reactivity, MT, and evoked vasoconstriction were measured in the isolated, pressurized arteries as described (48). MT at 70 mmHg pressure was expressed as a percentage of the passive external diameter (PD ≈ 135 μm at 70 mmHg), measured in Ca2+-free physiological salt solution (Ca2+-free PSS) at the end of each experiment. Myogenic reactivity is shown as the steady-state arterial diameter in PSS, as a function of intralumenal pressure, compared with the PD (in Ca2+-free PSS) at the same pressure.

[Ca2+]Cyt and GFP fluorescence measurements.

For simultaneous [Ca2+]Cyt and diameter measurements, pressurized arteries from WT mice were loaded with fluo-4. Details of the dye-loading procedure and imaging methods are published (48). Similar methods were used for GFP fluorescence measurements in NCX1SM−/− arteries. Briefly, the pressurized arteries were imaged with a Nipkow-Yokogawa spinning disc confocal imaging system (CSU-10; Solamere Technology, Salt Lake City, UT) mounted on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope (×60; numerical aperture, 1.2; water immersion objective). Fluorescence was excited at 488 nm (argon ion laser). Optical sections of the arterial wall (106 μm × 70 μm, and containing 20–35 cells) were imaged with a Stanford XR-Mega 10 camera (Stanford Photonics, Palo Alto, CA) at 1–30 frames/s using a video-capture board (PCI 1407, National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Immunoblot Analysis

Aorta, main mesenteric artery, urinary bladder, heart, and brain were dissected, minced, and homogenized in homogenization medium, and the membrane fractions were prepared to assay NCX protein expression. Tissue extracts were analyzed (48) with specific monoclonal NCX1 antibody (R3F1, from K. D. Philipson, University of California, Los Angeles, CA). Band intensities were quantified with ID image analysis software (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) (17) and normalized with β-actin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase to control for protein loading.

Arterial Myocyte Isolation

Male WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice (12–16 wk of age) were euthanized with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. The main mesenteric artery was removed, cleaned, and used for myocyte isolation. The artery was digested for 35 min at 37°C in low-Ca2+ PSS containing (in mg/ml) 1.5 collagenase type XI, 0.16 elastase type IV, and 1 bovine serum albumin, and individual myocytes were dissociated by trituration (2, 47). Only cells with elongated morphology (i.e., relaxed cells) were studied.

Patch-Clamp Recording

Whole cell, patch-clamp configuration was applied to record membrane currents using an Axopatch 200 patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), as described (47). Fire-polished micropipettes (1–3 MΩ resistance) were manufactured from borosilicate capillary tubing (Garner Glass, Claremont, CA) using a micropipette puller (model P-97, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). An Ag-AgCl reference electrode was connected to the bath using an agar salt bridge containing 1 M KCl. Before the pipette approached the cell, the chamber was perfused with Ca2+-free PSS containing 1.4 mM extracellular Mg2+ concentration to prevent cell contraction caused by ATP diffusing from the pipette. After seal formation, the cells were superfused with normal PSS. The holding potential was −70 mV in all experiments. The leak and capacity transients were subtracted using a P/4 protocol. The series resistance was compensated to give the fastest possible capacity transient without producing oscillations. The membrane currents were recorded with 12-bit analog-to-digital converters (Digidata 1322A, Axon Instruments). Data were sampled at 500 kHz (unless otherwise stated), filtered at 5 kHz with a 902LPF low-pass Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA), and stored for subsequent analysis. All records were obtained at room temperature (25–26°C).

Macroscopic currents were recorded using 15-ms voltage clamp steps to a range of potentials from −50 to +90 mV. Preliminary experiments showed that LVGC currents carried by Ca2+ were small and difficult to measure accurately; therefore, we used Ba2+ as the current carrier. To construct current-voltage curves, the current during the pulse (IBa) is plotted as a function of pulse voltage. Because the amplitude of the tail current following the pulse (−Itail) is a measure of the conductance activated during the pulse, conductance-voltage (G–V) curves are obtained by plotting −Itail as a function of pulse voltage.

Recording of Ca2+ Sparklets

Detailed methods for recording Ca2+ sparklets are published (28, 29). Briefly, Ca2+ sparklets were recorded using a total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (Olympus, South Windsor, CT). Cells were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-5F. Images were acquired at 30–90 Hz. Background-subtracted fluorescence signals were converted to concentration units using the Fmax equation (28, 47). Ca2+ sparklets were detected and defined for analysis using an automated algorithm written in Interactive Data Language software (IDL, Research Systems, Boulder, CO). Ca2+ sparklets had an amplitude equal to or larger than the mean basal [Ca2+]Cyt plus three times its standard deviation. For a [Ca2+]Cyt elevation to be considered a sparklet, a grid of 3 × 3 contiguous pixels had to have a [Ca2+]Cyt value at or above the amplitude threshold.

Reagents and Solutions

The artery dissection solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 2 MOPS, 0.02 EDTA, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2·2H2O, 5 glucose, and 2.0 pyruvate and 1% albumin (pH 7.4 at 5°C). The PSS perfusion solution contained (in mM) 112 NaCl, 25.7 NaHCO3, 4.9 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4·7H2O, 1.2 KH2PO4, 11.5 glucose, and 10 HEPES (adjusted pH to 7.3–7.4 with NaOH). High (10–75 mM) extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) solution was made by replacing NaCl with an equimolar KCl of normal PSS. Ca2+-free solution was made by omitting Ca2+ and adding 0.5 mM EGTA. Low (25.7 mM) extracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]o) solution was made by replacing 112 mM NaCl with equimolar LiCl; 25.7 mM NaHCO3 was retained to minimize the perturbation of the acid-base balance. Solutions were gassed with 5% O2-5% CO2-90% N2 (48).

The tissue homogenization medium contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 10 NaH2PO4, 2 EDTA, and 10 NaN3 and 2.5× concentrated Roche (Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ) complete protease inhibitor cocktail.

To isolate Ba2+ currents (IBa) in electrophysiological experiments, the pipette was filled with high Cs+ solution of the following composition: (in mM) 130 CsCl, 2.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, and 2 Na2ATP (pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). The bath solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 10 BaCl2, and 10 HEPES (pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). All experiments were performed in the presence of 200 nM tetrodotoxin (TTX) to block the Na+ currents previously described in these cells (2). The osmolarity of all internal and external solutions was maintained at 271 and 296 ± 1 mosmol/l, respectively. Osmolarity was measured with a model 5500 vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor, Logan, UT).

Reagents and sources were as follows: ouabain, phenylepherine, nifedipine, collagenase, elastase, and bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); SEA0400 (Taisho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan); and TTX and Bay K 8644 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Other reagents were reagent grade or the highest grade available. TTX was dissolved in deionized water; nifedipine was dissolved in DMSO.

Data Analysis and Statistics

The data are expressed as means ± SE; n denotes the number of animals, the number of arteries studied (1 artery per animal), or the number of cells studied in electrophysiological experiments. Comparisons of data were made using Student's paired or unpaired t-test, as appropriate; one-way or two-way ANOVA was used where indicated. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Electrophysiological data analysis was performed using pClamp software (version 9.0; Axon Instruments). IBa amplitudes were measured relative to the current level before the pulse.

To characterize the voltage dependence of LVGC activation, we fit G–V curves with a Boltzman equation of the following form:

where −Itail(Vm) is the magnitude of Itail following a step to Vm, −Itail,max is the maximum tail current, V0.5 is the voltage at which the conductance (i.e., the −Itail magnitude) is half-maximal, and k is the slope factor.

RESULTS

NCX1 Protein Expression Is Reduced in NCX1SM−/− Mouse Arteries

The expression of Cre recombinase, and thus the excision of NCX1 exon 11 in arterial myocytes of NCX1SM−/− mice, was verified by the simultaneous expression of eGFP. GFP fluorescence was observed in about 75–90% of the myocytes in the NCX1SM−/− mouse mesenteric small arteries employed in physiological experiments (Fig. 1C). There was, however, substantial variability not only from artery to artery but also from region to region in a single artery. The absence of a GFP signal in some myocytes (Fig. 1C) may indicate that Cre was not expressed in these cells or that it was only transiently expressed, in which case, NCX1 exon 11 should already have been excised.

The downregulation of normal NCX1 expression in these arteries was confirmed by immunoblot. In cardiac muscle, NCX1 appears as two bands, at 160 and 120 kDa. The relative expression of these bands varies, however, depending on the redox conditions used for membrane preparation (14); the 120-kDa band predominates under our conditions (Fig. 1D). In cardiac-specific knockout of NCX1, the intensities of both bands are reduced and a new, truncated NCX1 band appears at ∼110 kDa (18). As illustrated in Fig. 1D, comparable results are obtained in the arteries of WT and NCX1SM−/− mice, although some bands appear slightly smaller (∼140, ∼120, and ∼90 kDa, respectively). Only the two larger bands are observed in arteries from WT mice. The intensity of the 120-kDa band, which predominates in WT arteries, is reduced by about half in NCX1Fx/− mouse arteries and by ∼80–90% in NCX1SM−/− arteries; a new, truncated, ∼90-kDa band is then observed. The NCX1 expression is similarly reduced in urinary bladders from NCX1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− mice (Fig. 1D). Quantification is difficult, however, because of the change in band size and the apparent degradation of the truncated, nonfunctional protein. In contrast, both hearts (Fig. 1D) and brains (not shown) from NCX1SM−/− as well as NCX1Fx/− mice express about half the normal (WT) level of NCX1, because both genotypes have one global, null-mutant NCX1 allele, but the SM-specific Cre recombinase is not activated in these tissues. In sum, these data demonstrate that the marked knockdown of NCX1 expression in NCX1SM−/− mice is SM specific; moreover, homozygous global knockout is embryonic lethal (39).

BP is Modestly Reduced in NCX1SM−/− Mice

NCX1SM−/− mice appear normal and grow to adulthood, and there are no obvious behavioral or gross anatomical differences between these mice and either the WT or NCX1Fx/− controls. Nevertheless, the fact that mice which overexpress NCX1 in SM have elevated BP (21) indicates that NCX1 plays a role in BP regulation and suggests that NXC1SM−/− mice might also have a vascular phenotype. To test this, we compared BP in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice with two invasive methods (Fig. 2). First, the mean arterial BP (MBP) was measured with an intrafemoral catheter in mice under light isoflurane anesthesia. The results revealed that MBP in NCX1Fx/− mice was comparable with WT controls and was significantly reduced in NCX1SM−/− mice (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with telemetric BP measurements on awake, free-moving mice: MBP was lower in NCX1SM−/− mice than in NCX1Fx/− or WT mice (Fig. 2B,a). Interestingly, the heart rate was significantly slower in both NCX1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 2B,b). The similarity of the heart rate in NCX1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− mice, despite the difference in BP, implies that the slow heart rate does not account for the low BP in the NCX1SM−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

Blood pressure (BP) and heart rate in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice. A: mean BP (MBP) measured by intrafemoral catheter under light isoflurane anesthesia in 20 WT, 16 NCX1Fx/−, and 23 NCX1SM−/− mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. B: MBP (a) and heart rate (HR; b), measured by telemetry during the light-on (low activity) 12 h on the indicated days over a 16-day period. bpm, Beats/min. Two-way ANOVA for the indicated pairs: *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; n = 11 WT, 5 NCX1Fx/−, and 7 NCX1SM−/− mice.

MT and Reactivity Are Attenuated by Reduced NCX1 Activity

To determine the contractile properties of the arteries from NCX1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− mice, the diameter changes in isolated, pressurized mesenteric small arteries were measured. These arteries constrict spontaneously (=myogenic reactivity) when intralumenal pressure is increased to more than 40 or 50 mmHg during superfusion with PSS at 35–37°C (48). Arteries from NCX1SM−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced myogenic reactivity (Fig. 3A) and MT (Fig. 3B) than did WT or NCX1Fx/− arteries.

Fig. 3.

Effect of reduced NCX1 activity on myogenic reactivity (MR) and tone (MT) in pressurized mouse mesenteric small arteries. A: MR in WT (n = 7) and NCX1SM−/− (n = 5) mouse arteries. The data are shown as the mean steady-state arterial diameter of arteries superfused with PSS and the passive diameter (PD; in Ca2+-free PSS) at each pressure indicated on the abscissa. ***P < 0.001 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA). B: MT in WT (n = 9), NCX1Fx/− (n = 5), and NCX1SM−/− (n = 11) mouse arteries treated with 1 μM SEA0400. The data are normalized to the WT control (Ctrl) myogenic tone (MTCtrl). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. C,a: fluorescent images of a longitudinal cross-section through the left-hand wall of an artery loaded with fluo-4 before (i), during (ii), and after (iii) treatment with 1 μM SEA0400 (see C,b). Bright areas (see left-hand image) are individual myocytes in cross-section. C,b: time course of changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]Cyt; i.e., fluo-4 fluorescence, in arbitrary units, AU) for the entire wall (blue line) and for the two bright cells in the small boxes in the left-hand image (green and red lines). Simultaneous diameter changes are indicated by the black line. The times when images C,a, i–iii, were captured are shown on the graph. Results are representative of data from 5 arteries.

Figure 3B illustrates the effects of the specific NCX inhibitor, SEA0400 (25), on MT in these arteries. SEA0400 (1 μM) reduced MT in WT mouse arteries to about the level of MT observed in NCX1SM−/− arteries in the absence of SEA0400 but had no effect on MT in NCX1SM−/− arteries. Thus the effect of SEA0400 on WT arteries is comparable with the effect of genetic NCX1 ablation. This lack of effect on arteries with markedly reduced NCX1 expression and the attenuated effect on MT in NCX1Fx/− arteries (Fig. 3B) are evidence for the specificity of 1 μM SEA0400.

Data on the mechanism by which SEA0400 reduces MT were obtained by simultaneous measurements of [Ca2+]Cyt and diameter in WT arteries (Fig. 3C). Previously, we demonstrated that the generation of MT is associated with a sustained rise in [Ca2+]Cyt in myocytes within the walls of pressurized small arteries (48). The confocal images of a fluo-4-loaded WT artery wall in Fig. 3C,a show that [Ca2+]Cyt (i.e., fluo-4 fluorescence) declines and the artery dilates when 1 μM SEA0400 is applied (Fig. 3, C,a, i to ii, and C,b). [Ca2+]Cyt rises and the artery constricts when the SEA0400 is washed out (Fig. 3, C,a, ii to iii, and C,b). The incomplete recovery of both fluo-4 fluorescence and MT were likely primarily due to the slow and incomplete washout of SEA0400, which is very hydrophobic. A modest bleaching of fluo-4, however, probably also contributed to the incomplete recovery of the initial fluorescent signal.

A supplemental video clip of the fluo-4 fluorescence data shown in Fig. 3C is available (note: supplemental material may be found posted with the online version of this article). These data imply that Ca2+ entry via NCX1 contributes to the maintenance of the elevated [Ca2+]Cyt and MT in pressurized small arteries.

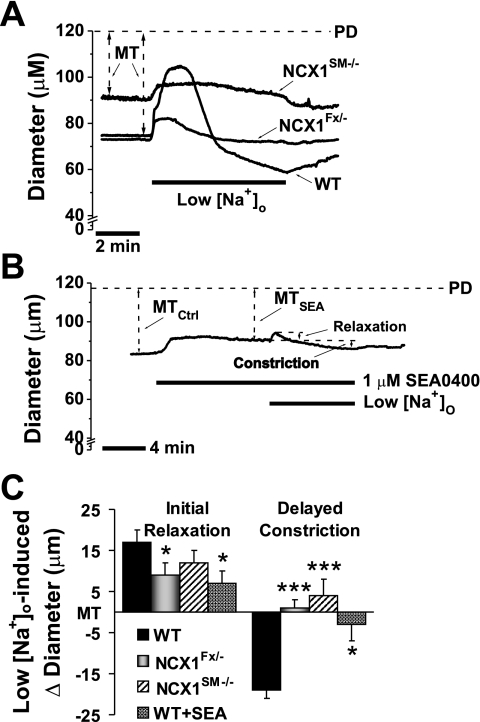

NCX1 Function Is Markedly Reduced in NCX1SM−/− Arteries

Additional evidence that arterial myocyte NCX1 activity is markedly reduced in NCX1SM−/− mice was obtained by exposing arteries to low (25.7 mM) [Na+]o solution for 7–10 min before restoring normal (137.7 mM) [Na+]o. In this common test of NCX function (1), the exposure of WT arteries to a sudden reduction in ENa induces an initial, transient vasodilation, followed by a sustained vasoconstriction (Fig. 4A). A preincubation of WT arteries with 1 μM SEA0400 for 10 min to block NCX reduces the dilation by about 50% and the constriction by about 90% (Fig. 4B). Importantly, the magnitudes of both the transient vasodilation and the sustained vasoconstriction are similarly reduced in NCX1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− arteries (Fig. 4, A and C).

Fig. 4.

Effect of reducing extracellular Na+ concentration ([Na+]o) on MT in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries and in WT arteries treated with SEA0400 (SEA). A: representative experiments show the effects of acute inhibition of NCX1 by lowering [Na+]o from 137.7 to 25.7 mM on MT in a WT, a NCX1Fx/−, and a NCX1SM−/− mouse artery. B: representative experiment shows the effect of 1 μM SEA0400 on low [Na+]o-induced vasodilation and vasoconstriction in a WT artery. C: summary of effects of lowering [Na+]o on the initial relaxation and delayed vasoconstriction in WT (n = 7), NCX1Fx/− (n = 9), and NCX1SM−/− (n = 16) arteries and WT arteries treated with 1 μM SEA0400 (n = 4). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 vs. WT.

We have reported that nanomolar ouabain raises [Ca2+]Cyt and augments MT in WT arteries; these effects are markedly inhibited by 1 μM SEA0400, suggesting that they result from increased NCX-mediated Ca2+ entry (21, 48). To explore this role of NCX further, we compared the effects of ouabain on MT in arteries from WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice. As illustrated in Fig. 5, A and B, the ability of 100 nM ouabain to augment MT is significantly impaired in NCX1Fx/− and, to a greater extent, in NCX1SM−/− arteries.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ouabain (Ouab) on MT in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries. A: effect of 100 nM Ouab on MT in 8 WT, 3 NCX1Fx/−, and 12 NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 for the indicated pairs. B: Ouab-induced increase in MT. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. WT.

Agonist-Induced Vasoconstriction Is Impaired in NCX1SM−/− Arteries

The effect of reduced NCX1 expression on high [K+]o- and phenylephrine (PE)-evoked vasoconstriction in small arteries are illustrated in Fig. 6. The maximal vasoconstriction induced by elevating [K+]o from 5 to 75 mM in NCX1Fx/− arteries, ∼60% of PD (which nearly obliterated the lumen), is similar to that in WT arteries (Fig. 6A,a). In contrast, the 75 mM [K+]o-induced vasoconstriction is significantly reduced in NCX1SM−/− arteries (Fig. 6A, a and b). This may indicate that the maximal Ca2+ entry through LVGCs is reduced in NCX1SM−/− arteries because the 75 mM [K+]o-evoked vasoconstriction is abolished by the LVGC blocker, nifedipine (47).

Fig. 6.

High extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o)- and phenylephrine (PE)-induced vasoconstriction in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries. A,a: vasoconstriction (as a percentage of PD) induced by elevating [K+]o from 5 to 75 mM in 8 WT, 11 NCX1Fx/−, and 7 NCX1SM−/− arteries; *P < 0.05. A,b: [K+]o concentration-vasoconstriction curves for 7 NCX1Fx/− and 5 NCX1SM−/− arteries; P < 0.01 (2-way ANOVA). B,a: PE (100 μM)-induced vasoconstriction in 5 WT, 5 NCX1Fx/−, and 5 NCX1SM−/− arteries; *P < 0.05. B,b: PE dose-response curves for 5 NCX1Fx/− and 5 NCX1SM−/− arteries; P < 0.001 (2-way ANOVA).

The maximal constriction to high-dose (3–100 μM) PE also is significantly smaller in NCX1SM−/− than in WT arteries; the constriction to 100 μM PE is slightly, but not significantly, reduced in NCX1Fx/− arteries (Fig. 6B, a and b). Furthermore, both the high [K+]o (Fig. 6A,b) and PE (Fig. 6B,b) dose-response curves are significantly depressed in NCX1SM−/− compared with in NCX1Fx/− arteries. Thus, for example, the PE constriction is reduced at all PE concentrations, but the concentration required for half-maximal constriction, ∼0.35 μM, is not significantly different in the NCX1SM−/− and WT mouse arteries (Fig. 6B,b). The differences between the NCX1SM−/− and NCX1Fx/− arteries at the low-dose ends of the respective curves can be attributed, at least in part, to the lower MT in the NCX1SM−/− arteries (i.e., at 5 mM [K+]o and at 0 mM PE). Some possible mechanisms for the reduced constriction to high [K+]o and high concentrations of PE are described in discussion.

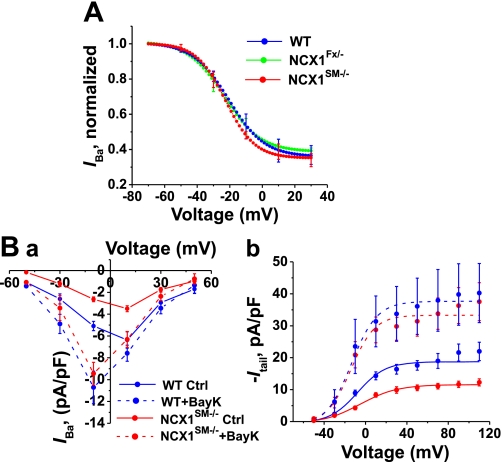

LVGC Current Is Reduced in NCX1SM−/− Myocytes

The aforementioned studies on high [K+]o-induced vasoconstriction raise the possibility that LVGC activity might be reduced in NCX1SM−/− myocytes. Therefore, LVGC currents were measured in isolated mesenteric artery myocytes, using Ba2+ as the current carrier (47). Indeed, the data reveal that LVGC currents in NCX1SM−/− mouse myocytes are smaller than the currents in myocytes from WT and NCX1Fx/− mice (Fig. 7A, a–c). This was confirmed by measuring both the current-voltage and G-V curves in myocytes from WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− mice. The amplitude of the LVGC, −Itail, was used as a measure of the conductance activated during the preceding depolarizing pulse (Fig. 7A,d). Both the LVGC current and conductance are significantly smaller in NCX1SM−/− myocytes compared with WT myocytes (Fig. 7B, a and b). LVGC currents and conductances are, however, nearly identical in WT and NCX1Fx/− myocytes (Fig. 7B, a and b).

Fig. 7.

Effects of genetic and pharmacological reduction of NCX activity on L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (LVGC) current and conductance in WT, NCK1Fx/−, and NCK1SM−/− mouse mesenteric artery myocytes. A: representative of LVGC current records. A, a–c: families of macroscopic LVGC-mediated Ba2+ currents (IBa) recorded in response to voltage-clamp steps to −50, −30, −10, +10, and +30 mV in a myocyte from a WT (a), a NCX1Fx/− (b), or a NCX1SM−/− (c) mouse, respectively. A,d: illustration of current measurements used to construct current-voltage (I–V) and conductance-voltage (G–V) curves. The maximum current during the voltage-clamp step, IBa, is plotted as a function of the voltage during the step to construct I–V curves; the amplitude of the tail current (Itail) is a measure of the conductance (G) activated during the preceding step. G–V curves are constructed by plotting −Itail as a function of the Vm during the preceding step. Scale bars (in A, b and d) represent 100 pA, 5 ms. B: whole cell LVGC currents were measured during voltage-clamp steps to −50 to +50 mV. B,a: I–V curves. The currents from WT (38 cells from 24 mice) and NCX1Fx/− (35 cells from 11 mice) are similar, whereas the currents from NCX1SM−/− (40 cells from 8 mice) are significantly smaller: P < 0.01 at +10 mV. B,b: G–V curves from the same myocytes as in B,a. The amplitude of Itail is plotted vs. Vm. The maximum LVGC conductance is significantly smaller in NCX1SM−/− myocytes than in either WT or NCX1Fx/− myocytes (P < 0.001; 2-way ANOVA). C: effect of SEA0400 on IBa in dialyzed WT myocytes. IBa at +10 mV is plotted as a function of time. Addition of 0.01% DMSO or 1 μM SEA0400 in 0.01% DMSO at the times indicated had no significant effect on the amplitude of IBa. Similar results were obtained in 12 cells from 5 WT mice.

Block of NCX1 with SEA0400 Does Not Affect LVGC Current

Because the LVGC current is reduced in NCX1SM−/− mice, we examined the effect of acute block of NCX1 with SEA0400 on LVGC current in dialyzed, patch-clamped WT myocytes. In the experiment illustrated in Fig. 7C, IBa at +10 mV is plotted as a function of time to control for the rundown of the current. The addition of 0.01% DMSO or 1 μM SEA0400 in 0.01% DMSO had no detectable effect on IBa. In another type of control experiment performed in a similar manner, ∼85–90% of IBa was blocked by 10 μM nifedipine within 30 s (data not shown) (47). These experiments demonstrate that an acute block of NCX1 by SEA0400 in WT myocytes does not reduce the nifedipine-sensitive LVGC current.

Voltage-Dependent Inactivation of LVGC Channels Is Unchanged in NCX1SM−/− Myocytes

In cardiac-specific NCX1 knockout mice, too, LVGC current is decreased. In those myocytes, the current declines as a result of an increase in the rate of Ca2+-induced inactivation and increased Ca2+-dependent tonic inactivation of LVGCs, presumably because of the elevation of subsarcolemmal [Ca2+] (32). Such a mechanism cannot explain our results because Ba2+ was used as the current carrier in the arterial myocytes and because Ba2+ does not support Ca2+-dependent inactivation (15). Because LVGCs also exhibit voltage-dependent inactivation, however, we tested whether a shift in voltage dependence or an increase in inactivation could explain the reduction of LVGC current in NCX1SM−/− mice. The results reveal that voltage-dependent inactivation is nearly identical in WT, NCX1Fx/−, and NCX1SM−/− myocytes (Fig. 8A). Thus a change in inactivation cannot explain the reduction of LVGC current in NCX1SM−/− myocytes.

Fig. 8.

Voltage-dependent inactivation of IBa and effects of Bay K 8644 (BayK) on IBa in WT and NCX1 mutant arterial myocytes. A: voltage-dependent inactivation of LVGCs. IBa at +10 mV was measured following 10-s inactivating prepulses to voltages from −70 to +30 mV. IBa, normalized relative to its maximum value, is plotted vs. prepulse voltage. As prepulse voltage becomes more positive, IBa decreases because of voltage-dependent inactivation. These inactivation curves are nearly identical in WT (24 cells from 12 mice), NCX1Fx/− (15 cells from 5 mice), and NCX1SM−/− (22 cells from 7 mice) myocytes. B,a: I–V curves from WT (13 cells from 9 mice) and NCX1SM−/− (11 cells from 6 mice) myocytes with and without 1 μM Bay K 8644, the LVGC activator. B,b: G–V curves from the same cells as in B,a. In the absence of Bay K 8644, the LVGC current and conductance are smaller in NCX1SM−/− compared with WT myocytes (also see Fig. 7B). Bay K 8644 increases the current and conductance more in NCX1SM−/− than in WT myocytes and thereby eliminates the difference in current and conductance amplitude between WT and NCX1SM−/− myocytes.

Bay K 8644 Eliminates the Difference in LVGC Current Between Control and NCX1SM−/− Myocytes

Another possible explanation for the reduced LVGC current in NCX1SM−/− myocytes is that the expression of the channels is reduced. To get an indication of LVGC expression, we applied Bay K 8644, a potent activator of LVGCs (19). In both WT and NCX1SM−/− myocytes, 1 μM Bay K 8644 increased LVGC current and maximum conductance and shifted the G–V curve to more negative potentials (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, the current and conductance increases were greater in NCX1SM−/− myocytes than in WT myocytes. In fact, Bay K 8644 eliminated the difference between the current, as well as the conductance, in WT and NCX1SM−/− myocytes (Fig. 8B). This implies that LVGC channel expression is comparable in WT and NCX1SM−/− myocytes.

Bay K 8644 Eliminates the Difference in Ca2+ Sparklet Activity Between Control and NCX1SM−/− Myocytes

Ca2+ sparklets are local Ca2+ signals produced by the opening of single or small clusters of LVGCs in arterial myocytes (28, 29). Accordingly, Ca2+ sparklets are the elementary events underlying dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ influx in these cells. Therefore, in view of the smaller LVGC currents in NCX1SM−/− than in WT or NXC1Fx/− myocytes, we examined Ca2+ sparklet activity in NCX1SM−/− and sibling NXC1Fx/− mouse myocytes to test the hypothesis that sparklet activity is reduced in the NCX1SM−/− myocytes.

The images in Fig. 9A show a representative Ca2+ sparklet recorded from an NCX1SM−/− myocyte and one from an NXC1Fx/− myocyte. Summarized data indicate that the mean peak amplitude of the sparklets, as well as the width at 50% of peak amplitude, is comparable in NXC1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− myocytes: 41 ± 1 vs. 40 ± 1 nM, and 0.73 ± 0.03 vs. 0.82 ± 0.05 μm (n = 7 and 9 cells, respectively; P > 0.05 for both comparisons). These results suggest that NCX1-mediated Ca2+ transport does not significantly alter the amplitude or spatial spread of quantal Ca2+ sparklets.

Fig. 9.

Ca2+ sparklets in NCK1Fx/− and NCK1SM−/− mouse artery myocytes. A: selected images show Ca2+ sparklets (circled) recorded under control conditions. The traces of changes in [Ca2+]Cyt (Δ[Ca2+]Cyt) as a function of time suggest that sparklet activity is greater in NXC1Fx/− than in NCX1SM−/− myocytes. Bay K 8644 (500 nM) increases sparklet activity in both types of myocytes; control (Ctrl) and Bay K 8644 traces were recorded from the same myocytes. Vertical scale bars are 50 nM in all traces. B: number of sparklet sites/μm2 in 8 NXC1Fx/− and in 7 NCX1SM−/− myocytes in the absence (Ctrl) and presence of 500 nM Bay K 8644; *P < 0.05. C: the sparklet activity (nPs; n = number of quantal levels; Ps = probability that a sparklet site is active) is plotted for 8 NXC1Fx/− and 7 NCX1SM−/− myocytes in the absence (Ctrl) and presence of 500 nM Bay K 8644; *P < 0.05. Note that Bay K 8644 abolished the differences between NXC1Fx/− and NCX1SM−/− myocytes in B and C.

Despite these similarities in the quantal events, Ca2+ sparklet density (in sites/mm2) and the overall level of sparklet activity (in nPs, where n is the number of quantal levels and Ps is the probability that a sparklet site is active) (29) are significantly reduced in NCX1SM−/− myocytes compared with NXC1Fx/− myocytes (Fig. 9, A and B). Bay K 8644 (500 nM), however, abolishes this difference (Fig. 9, B and C). These results are consistent with the effect of Bay K 8644 on LVGC currents in NCX1SM−/− and control (WT) myocytes (Fig. 8B).

Bay K 8644 Does Not Eliminate the Difference in Myogenic Reactivity Between WT and NCX1SM−/− Arteries

Because LVGCs play a major role in myogenic constriction (8, 20), one possibility is that the reduced myogenic reactivity observed in NCX1SM−/− arteries (Fig. 3A) might be the result of the reduced LVGC activity in these arteries. Bay K 8644 normalizes LVGC current (Fig. 8) and Ca2+ sparklet activity (Fig. 9) in NCX1SM−/− arteries. Therefore, we reexamined the myogenic reactivity curves in WT and NCX1SM−/− arteries in the presence of 1 μM Bay K 8644. Figure 10 shows that Bay K 8644 constricts WT and NCX1SM−/− arteries at 20 mmHg. The WT arteries then exhibit slight additional constriction when the intralumenal pressure is increased to 40 mmHg or more. In contrast, raising intralumenal pressure from 20 to 40 mmHg dilates the Bay K 8644-treated NCX1SM−/− arteries, albeit, not as much as in the absence of Bay K 8644, increasing intralumental pressure further, and then causes only slight constriction. Importantly, Bay K 8644 did not affect the PD in either WT or NCX1SM−/− arteries (not shown). Clearly, the NCX1SM−/− arteries exhibit significantly less myogenic constriction than WT arteries at intralumenal pressures of 40–120 mmHg, even in the presence of Bay K 8644. This difference apparently cannot be attributed to the reduced LVGC activity in NCX1SM−/− arterial myocytes.

Fig. 10.

Effect of Bay K 8644 on MR in pressurized mouse mesenteric small arteries. MR in untreated WT (n = 7) and NCX1SM−/− (n = 5) mouse arteries (solid lines; data from Fig. 3A) and 1 μM Bay K 8644-treated arteries (dashed lines; n = 3 each). The data are the normalized (to PD at 120 mmHg) mean steady-state diameters of arteries superfused with PSS ± 1 μM Bay K 8644 and the PD (in Ca2+-free PSS) at each pressure indicated on the abscissa. The WT artery MR curve differed significantly (2-way ANOVA) from the NCX1SM−/− artery MR curve both in the absence of Bay K 8644 (black lines and symbols; P < 0.001) and in its presence (gray lines and symbols; P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

This study on the functional consequences of SM-specific knockout of NCX1 complements our earlier report that SM-specific overexpression of NCX1 elevates BP in mice (21). The results we describe here strengthen the view that NCX1 plays an important role in vascular function.

NCX1Fx/− Mice vs. WT Mice

A complication encountered in this study was the discovery that the Cre recombinase gene, under the control of the SM-MHC promoter, is activated during gametogenesis. Thus both the CreSM+ and Cre− mice used in this study all carried one floxed NCX1 allele and one null-mutant allele, in which NCX1 exon 11 was permanently deleted in all cells (methods). In other words, both Cre− and CreSM+ mice are, effectively, NCX1 heterozygotes; then, upon activation of the Cre gene in the SM cells of CreSM+ mice, exon 11 in the remaining floxed NCX1 allele is excised in these cells. Therefore, in many experiments, we employed two controls for the NCX1SM−/− mice: WT mice and NCX1Fx/− mice. It is noteworthy that the homozygous global null mutation of NCX1 is embryonic lethal (39).

Relative to WT controls, the NCX1Fx/− mice have a reduced expression of full-length NCX1 in all tissues tested (see Fig. 1D). As a result, the NCX1Fx/− arteries exhibit a reduced vasodilator response to SEA0400 (Fig. 3B), a reduced low [Na+]o-induced vasodilation and vasoconstriction (Fig. 4B), and a reduced vasoconstrictor response to low-dose ouabain (Fig. 5). In many other respects, however, the function of NCX1Fx/− arteries is comparable with that of WT controls. For example, MT, vasoconstrictor responses to high [K+]o, and the function of LVGCs are all normal; moreover, the NCX1Fx/− mice have normal BP. The implication is that approximately half of the normal level of NCX1 in ASMC is sufficient to maintain normal arterial function.

Similarity of Effects of Genetic and Pharmacological Knockout of NCX1 on Arterial Function

In contrast to the situation in NCX1Fx/− mice, vascular function is substantially impaired in NCX1SM−/− mice. This is exemplified by the reduced myogenic reactivity and MT (Fig. 3), attenuated vasoconstrictor responses to PE and high [K+]o (Fig. 6), and reduced LVGC activity (Fig. 7). Moreover, SM-specific knockout of NCX1 and an acute SEA0400 application to WT mouse arteries, i.e., a genetic and pharmacological reduction of NCX activity, respectively, have comparable effects on MT (Fig. 3) and on the responses to low [Na+]o (Fig. 4) and low-dose ouabain (Fig. 5 and Ref. 48). In rat small arteries, too, pharmacological blockade or antisense oligonucleotide knockdown of NCX1 reduces myogenic reactivity and tone (36). As expected for a NCX-specific blocker [albeit somewhat controversial (38)], SEA0400 has no effect on MT in NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries (Fig. 3) or on LVGC current in WT artery myocytes (Fig. 7C). These findings emphasize the importance of NCX1-mediated Ca2+ entry in arterial function. Clearly, this mode of NCX operation is a normal mode and, perhaps, the dominant mode in ASMCs in arteries with tone.

The NCX1-mediated, low [Na+]o-induced initial vasodilation and, later, sustained vasoconstriction (Fig. 4A) raise the interesting question of mechanism(s). The vasoconstriction appears to be explicable by the decline in the inwardly directed ENa; this is expected to promote net Ca2+ gain via NCX1 (Introduction) and direct activation of myosin light chain kinase and, therefore, ASMC contraction. The explanation for the early vasodilation is less clear. About half of the dilation is blocked by bath-applied SEA0400 or by SM-specific NCX1 knockout and therefore appears to be attributable to SM NCX1 (Fig. 4C). Two possible mechanisms that could also be triggered by NCX-mediated Ca2+ entry and a rise in [Ca2+]Cyt are 1) the rapid activation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in ASMCs (7) and 2) the Ca2+-induced activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells (43). The latter possibility is consistent with the view that NCX1 activity in ASMCs and endothelial cells may have opposing effects on arterial constriction.

Reduced LVGC Activation: Cause of Reduced MT or Consequence of Reduced NCX1 Activity?

An unexpected observation was that LVGC activity is reduced in arterial myocytes from NCX1SM−/− mice (Fig. 7). Three possible explanations are 1) a reduction in the number of expressed LVGCs in NCX1SM−/− myocytes or 2) a decrease in the magnitude of the LVGC-mediated elementary Ca2+ influx events (Ca2+ sparklets) in NCX1SM−/− myocytes (i.e., a decrease in quantal size), or 3) a reduction in the number of open channels under the physiological conditions that prevail in NCX1SM−/− myocytes. The maximal activation of LVGCs (both whole cell currents and Ca2+ sparklets) by Bay K 8644 reveals that the reduced channel activity is functional and is not due to reduced LVGC expression.

To distinguish between the second and third possibilities, we employed sparklet analysis. The evidence that the magnitude and spatial spread of individual sparklets do not differ in NCX1SM−/− and NCX1Fx/− myocytes indicates that the individual quanta are similar; this also implies that the single-channel conductance of the LVGCs is not altered. Thus the reduced LVGC current must be due to a decreased open-channel probability. This fits with the observed reduction in sparklet activity (number of active sites and probability of activation) in NCX1SM−/− myocytes (Fig. 9).

LVGC activity plays a critical role in the maintenance of MT (8, 20, 47), and the reduced LVGC activity might be the cause of the reduced MT and low BP in NCX1SM−/− mice. Figure 10 shows, however, that myogenic constriction is reduced in NCX1SM−/− arteries, compared with WT arteries, even in the presence of 1 μM Bay K 8644, which abolishes the difference between LVGC activity in these arteries (Fig. 8). Furthermore, evidence presented in the accompanying article (37) implies that the depressed LVGC activity is a consequence of the low [Ca2+]Cyt and reduced Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C activity that likely results from a marked knockdown of NCX1 expression. Indeed, an acute inhibition of NCX by SEA0400, which does not block LVGCs (Fig. 7C), lowers [Ca2+]Cyt and reduces MT in WT arteries (Fig. 3, B and C). The fact that NCX1SM−/− mouse arteries have significantly reduced MT therefore implies that [Ca2+]Cyt may also be low in these ASMCs. Thus the attenuation of MT (Fig. 3A), LVGC activity (Fig. 7), and high [K+]o-induced vasoconstriction (Fig. 6A) in NCX1SM−/− arteries may all be the consequence of a low [Ca2+]Cyt as a result of reduced NCX1-mediated Ca2+ entry.

The mechanism(s) responsible for the attenuated high-dose PE-induced vasoconstriction (Fig. 6B) is (are) uncertain. Preliminary data imply that the mobilization of stored Ca2+ (42) is not impaired in arteries from NCX1SM−/− mice because high PE-induced vasoconstriction in Ca2+-free media is not attenuated (data not shown). A likely possibility is that receptor-operated channels (ROCs), which are an important source of Ca2+ during receptor activation (44), especially at high catecholamine concentrations (30), may be downregulated in NCX1SM−/− arteries. In primary cultured arterial myocytes, a knockout of NCX1 markedly decreases the expression of transient receptor potential canonical 6 channel protein (a component of ROCs) and reduces ROC activity (33).

Correlation Between BP and In Vitro MT

Davis and Hill (8) observed that the level of tone in isolated arteries “is often comparable to that observed in the same vessels in vivo.” This implies that MT in isolated arteries predicts not only in vivo vascular tone but BP as well, as exemplified by the increased MT and elevated BP in α2 Na+-pump heterozygous null mutant mice (48). The present report extends this concept by showing that, at the other end of the spectrum, SM-specific knockout of NCX1 not only reduces MT but lowers BP as well. Conversely, SM-specific overexpression of NCX1 is associated with elevated BP (21); an increase in MT is anticipated, but this has not yet been tested in arteries from these mice.

Most important, the present report adds to the growing body of evidence that α2 Na+ pumps and adjacent NCX1 are critical mechanisms that link Na+ metabolism to BP regulation (6). Recently, Wirth and colleagues (45) suggested that salt-dependent hypertension is specifically mediated by a G12-G13 protein-coupled receptor-mediated pathway, but our findings do not support their conclusion. On the contrary, our results suggest that the modulation of NCX1 activity directly affects Ca2+ metabolism and the level of [Ca2+]Cyt and thus likely acts via myosin light chain kinase to modulate vasoconstriction. In conjunction with earlier reports (12, 13, 21, 48), the present study is consistent with the view that retained salt can act via the endogenous ouabain-α2 Na+ pump-NCX1 pathway to elevate BP without directly involving G protein-coupled receptor pathways (6). Of course, the downstream effects are likely to be modulated by the G protein-coupled receptor pathways that regulate the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus (24).

We conclude that the arterial SM NCX1 is needed to maintain the normal [Ca2+]Cyt, MT, and BP. This direct link to NaCl metabolism is often overlooked in studies of the mechanisms that influence the BP in salt-dependent hypertension.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a National Scientist Development grant from the American Heart Association (to J. Zhang); an International Society of Hypertension-Pfizer award (to J. Zhang); an National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases training grant (to L. K. Antos); and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute research grants (to M. P. Blaustein, K. D. Philipson, M. I. Kotlikoff, L. F. Santana, and W. G. Wier).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michelle Izuka for technical support and transgenic mouse genotyping and Katherine Frankel for assistance with the manuscript. We also thank Taisho Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan) for a gift of SEA0400.

Present address of C. Ren: Neuroscience program, Otolaryngology/Department of Surgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashida T, Blaustein MP. Regulation of cell calcium and contractility in mammalian arterial smooth muscle: the role of sodium-calcium exchange. J Physiol 392: 617–635, 1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berra-Romani R, Blaustein MP, Matteson DR. TTX-sensitive voltage-gated Na+ channels are expressed in mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H137–H145, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaustein MP. Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation, and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 232: C165–C173, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaustein MP, Lederer WJ. Sodium/calcium exchange: its physiological implications. Physiol Rev 79: 763–854, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaustein MP, Zhang J, Chen L, Song H, Raina H, Kinsey SP, Izuka M, Iwamoto T, Kotlikoff MI, Lingrel JB, Philipson KD, Wier WG, Hamlyn JM. The pump, the exchanger, and endogenous ouabain: signaling mechanisms that link salt retention to hypertension. Hypertension 53: 291–298, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner R, Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Eckman DM, Kosek JC, Wiler SW, Patterson AJ, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407: 870–876, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MJ, Hill MA. Signaling mechanisms underlying the vascular myogenic response. Physiol Rev 79: 387–423, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lange W, Halabi C, Beyer A, Sigmund C. Germ line activation of the Tie2 and SMMHC promoters causes noncell-specific deletion of floxed alleles. Physiol Genomics 35: 1–4, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Martino C, Capanna E, Nicotra MR, Natali PG. Immunochemical localization of contractile proteins in mammalian meiotic chromosomes. Cell Tissue Res 213: 159–178, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dibb KM, Graham HK, Venetucci LA, Eisner DA, Trafford AW. Analysis of cellular calcium fluxes in cardiac muscle to understand calcium homeostasis in the heart. Cell Calcium 42: 503–512, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dostanic-Larson I, Van Huysse JW, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The highly conserved cardiac glycoside binding site of Na,K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 15845–15850, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dostanic I, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Theriault S, Van Huysse JW, Lingrel JB. The α2-isoform of Na-K-ATPase mediates ouabain-induced hypertension in mice and increased vascular contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H477–H485, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durkin JT, Ahrens DC, Pan YC, Reeves JP. Purification and amino-terminal sequence of the bovine cardiac sodium-calcium exchanger: evidence for the presence of a signal sequence. Arch Biochem Biophys 290: 369–375, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert R, Tillotson DL. Calcium-mediated inactivation of the calcium conductance in caesium-loaded giant neurones of Aplysia californica. J Physiol 314: 265–280, 1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frutkin AD, Shi H, Otsuka G, Leveen P, Karlsson S, Dichek DA. A critical developmental role for tgfbr2 in myogenic cell lineages is revealed in mice expressing SM22-Cre, not SMMHC-Cre. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 724–731, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golovina VA, Song H, James PF, Lingrel JB, Blaustein MP. Na+ pump α2-subunit expression modulates Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C475–C486, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson SA, Goldhaber JI, So JM, Han T, Motter C, Ngo A, Chantawansri C, Ritter MR, Friedlander M, Nicoll DA, Frank JS, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Ross RS, Philipson KD. Functional adult myocardium in the absence of Na+-Ca2+ exchange: cardiac-specific knockout of NCX1. Circ Res 95: 604–611, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW. Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature 311: 538–544, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill MA, Zou J, Potocnik SJ, Meininger GA, Davis MJ. Arteriolar smooth muscle mechanotransduction: Ca2+ signaling pathways underlying myogenic reactivity. J Appl Physiol 91: 973–983, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamoto T, Kita S, Zhang J, Blaustein MP, Arai Y, Yoshida S, Wakimoto K, Komuro I, Katsuragi T. Salt-sensitive hypertension is triggered by Ca2+ entry via Na+/Ca2+ exchanger type-1 in vascular smooth muscle. Nat Med 10: 1193–1199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen BJ, De Celle T, Debets JJ, Brouns AE, Callahan MF, Smith TL. Effects of anesthetics on systemic hemodynamics in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1618–H1624, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynch RM, Weber CS, Nullmeyer KD, Moore ED, Paul RJ. Clearance of store-released Ca2+ by the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is diminished in aortic smooth muscle from Na+-K+-ATPase α2-isoform gene-ablated mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1407–H1416, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maguire JJ, Davenport AP. Regulation of vascular reactivity by established and emerging GPCRs. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 448–454, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda T, Arakawa N, Takuma K, Kishida Y, Kawasaki Y, Sakaue M, Takahashi K, Takahashi T, Suzuki T, Ota T, Hamano-Takahashi A, Onishi M, Tanaka Y, Kameo K, Baba A. SEA0400, a novel and selective inhibitor of the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, attenuates reperfusion injury in the in vitro and in vivo cerebral ischemic models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298: 249–256, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuoka S, Hilgemann DW. Steady-state and dynamic properties of cardiac sodium-calcium exchange. Ion and voltage dependencies of the transport cycle. J Gen Physiol 100: 963–1001, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakasaki U, Iwamoto T, Hanada H, Imagawa T, Shigekawa M. Cloning of the rat aortic smooth muscle Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and tissue-specific expression of isoforms. J Biochem (Tokyo) 114: 528–534, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Mechanisms underlying heterogeneous Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol 127: 611–622, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Votaw VS, Santana LF. Constitutively active L-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11112–11117, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pacaud P, Loirand G, Bolton TB, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Intracellular cations modulate noradrenaline-stimulated calcium entry into smooth muscle cells of rat portal vein. J Physiol 456: 541–556, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pott C, Ren X, Tran DX, Yang MJ, Henderson S, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Garfinkel A, Philipson KD, Goldhaber JI. Mechanism of shortened action potential duration in Na+-Ca2+ exchanger knockout mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C968–C973, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pott C, Yip M, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. Regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ current in Na+-Ca2+ exchanger knockout mice: functional coupling of the Ca2+ channel and the Na+-Ca2+ exchanger. Biophys J 92: 1431–1437, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulina MV, Zulian A, Berra-Romani R, Beskina O, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Baryshnikov SG, Papparella I, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Golovina VA. Upregulation of Na+ and Ca2+ transporters in arterial smooth muscle from ouabain hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H263–H274, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quednau BD, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. The sodium/calcium exchanger family-SLC8. Pflügers Arch 447: 543–548, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quednau BD, Nicoll DA, Philipson KD. Tissue specificity and alternative splicing of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger isoforms NCX1, NCX2, and NCX3 in rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C1250–C1261, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raina H, Ella SR, Hill MA. Decreased activity of the smooth muscle Na+/Ca2+ exchanger impairs arteriolar myogenic reactivity. J Physiol 586: 1669–1681, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren C, Zhang J, Philipson KD, Kotlikoff MI, Blaustein MP, Matteson DR. Activation of L-type Ca2+ channels by protein kinase C in smooth muscle-specific Na+/Ca2+ knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol ( January15, 2010). doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00965.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reuter H, Henderson SA, Han T, Matsuda T, Baba A, Ross RS, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. Knockout mice for pharmacological screening: testing the specificity of Na+-Ca2+ exchange inhibitors. Circ Res 91: 90–92, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reuter H, Henderson SA, Han T, Ross RS, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is essential for the action of cardiac glycosides. Circ Res 90: 305–308, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu H, Borin ML, Blaustein MP. Use of La3+ to distinguish activity of the plasmalemmal Ca2+ pump from Na+/Ca2+ exchange in arterial myocytes. Cell Calcium 21: 31–41, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slodzinski MK, Blaustein MP. Physiological effects of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger knockdown by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides in arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C251–C259, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Somlyo AV, Bond M, Somlyo AP, Scarpa A. Inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release and contraction in vascular smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 5231–5235, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teubl M, Groschner K, Kohlwein SD, Mayer B, Schmidt K. Na+/Ca2+ exchange facilitates Ca2+-dependent activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem 274: 29529–29535, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villalba N, Stankevicius E, Garcia-Sacristan A, Simonsen U, Prieto D. Contribution of both Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ sensitization to the alpha1-adrenergic vasoconstriction of rat penile small arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1157–H1169, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wirth A, Benyo Z, Lukasova M, Leutgeb B, Wettschureck N, Gorbey S, Orsy P, Horvath B, Maser-Gluth C, Greiner E, Lemmer B, Schutz G, Gutkind S, Offermanns S. G(12)-G(13)-LARG-mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat Med 14: 64–68, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin HB, Deng KY, Rishniw M, Ji G, Kotlikoff MI. Smooth muscle expression of Cre recombinase and eGFP in transgenic mice. Physiol Genomics 10: 211–215, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Berra-Romani R, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Striessnig J, Blaustein MP, Matteson DR. Role of Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels in vascular tone: effects of nifedipine and Mg2+. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H415–H425, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Lee MY, Cavalli M, Chen L, Berra-Romani R, Balke CW, Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Hamlyn JM, Iwamoto T, Lingrel JB, Matteson DR, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Sodium pump alpha2 subunits control myogenic tone and blood pressure in mice. J Physiol 569: 243–256, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang S, Dong H, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Upregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger contributes to the enhanced Ca2+ entry in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C2297–C2305, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.