Abstract

The marked sexual dimorphism that exists in human cardiovascular diseases has led to the dogmatic concept that testosterone (Tes) has deleterious effects and exacerbates the development of cardiovascular disease in males. While some animal studies suggest that Tes does exert deleterious effects by enhancing vascular tone through acute or chronic mechanisms, accumulating evidence suggests that Tes and other androgens exert beneficial effects by inducing rapid vasorelaxation of vascular smooth muscle through nongenomic mechanisms. While this effect frequently has been observed in large arteries at micromolar concentrations, more recent studies have reported vasorelaxation of smaller resistance arteries at nanomolar (physiological) concentrations. The key mechanism underlying Tes-induced vasorelaxation appears to be the modulation of vascular smooth muscle ion channel function, particularly the inactivation of L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels and/or the activation of voltage-operated and Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Studies employing Tes analogs and metabolites reveal that androgen-induced vasodilation is a structurally specific nongenomic effect that is fundamentally different than the genomic effects on reproductive targets. For example, 5α-dihydrotestosterone exhibits potent genomic-androgenic effects but only moderate vasorelaxing activity, whereas its isomer 5β-dihydrotestosterone is devoid of androgenic effects but is a highly efficacious vasodilator. These findings suggest that the dihydro-metabolites of Tes or other androgen analogs devoid of androgenic or estrogenic effects could have useful therapeutic roles in hypertension, erectile dysfunction, prostatic ischemia, or other vascular dysfunctions.

Keywords: 5α-dihydrotestosterone, 5β-dihydrotestosterone, hypertension, vascular relaxation, vasodilation

numerous clinical and epidemiological studies have established that marked sexual dimorphism exists in a variety of human cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). The well-established clinical observations that hypertension (HT) and coronary artery disease occur more frequently in men than in premenopausal women (26–28, 30, 31, 38, 69) have led to the dogmatic concept that testosterone (Tes) has deleterious effects on the heart and vasculature and exacerbates the development of CVD in males (18, 37, 54). However, clinical and epidemiological studies on the role of Tes in CVD are at best controversial, and recent in-depth reviews and analyses of the role of androgens in CVD reveal that there is little sound evidence from either animal or human studies that androgens shorten men's lives and recent human studies reveal both acute and chronic beneficial effects of Tes on coronary artery disease (31, 69). While some animal studies suggest that Tes may exert deleterious effects on the vascular wall by enhancing vascular tone through acute (63) or chronic mechanisms (18, 36, 57), accumulating evidence now suggests that Tes and other androgens exert protective effects on both cardiovascular and metabolic functions and may play important roles in the acute regulation of vascular function (44, 66). Indeed, numerous studies have now demonstrated that Tes exerts beneficial effects on cardiovascular function, among other effects, by inducing rapid vasorelaxation of vascular smooth muscle (VSM), as reviewed recently (44, 66). This acute effect of Tes and other androgens has been observed at micromolar concentrations in a variety of large arteries (aorta, coronary and umbilical arteries) as well as small resistance arteries (mesenteric, prostatic, pulmonary, and subcutaneous) from several animal species (rat, mouse, rabbit, pig, and dog) and humans (2, 8, 10, 32, 48, 60, 71). Interestingly, in studies employing small vessel wire myography, it has been reported that micromolar concentrations of Tes induce vasodilation of rat pulmonary arteries (23), human subcutaneous resistance arterioles (32), and porcine small prostatic arteries (43).

It is important to clarify that circulating plasma Tes concentrations in adult men range 11–36 nmol/l, whereas its 5α-reduced metabolite [5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT)] is present in plasma at levels about 10% that of Tes, ranging in most men between 1.0 and 2.9 nmol/l. However, it has been agreed that physiological concentrations of Tes are in the range of 100 pM–100 nM, whereas supraphysiological and pharmacological concentrations exceed 100 nM. In this respect, a significant vasodilation has also been observed at physiological (low nanomolar) concentrations of Tes in rat mesenteric arterioles (64, 68) and human pulmonary resistance arteries (55) in vitro. Furthermore, there is also the evidence that Tes produces coronary or systemic vasodilation in vivo at physiological concentrations (100 pM to 100 nM) in humans (67) and in canine and porcine animal models (3, 39). Moreover, in electrophysiological (patch clamp) experiments measuring ion currents in single VSM cells, Tes acts at nanomolar concentrations (8, 17, 41, 58, 59) and even at circulating (36 nmol/l) concentrations (17, 58, 59) to inhibit Ca2+ channels.

Mechanisms of Androgen-Induced Vasodilation

A variety of studies has clearly established that androgen-induced vasorelaxation is a rapid, nongenomic effect on the vascular wall (5, 11, 22, 46). Furthermore, it should be noted that numerous studies have shown that high pharmacological concentrations of Tes (10–100 μM) induce vasodilation in endothelium-denuded vessels, suggesting an endothelium-independent mechanism (8, 10, 12, 24, 47, 48, 60, 63, 73). In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that Tes-induced vasorelaxation from physiological to pharmacological concentrations (100 pM–10 μM) is inhibited significantly by the removal of the endothelium or treatment with NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, both in the rat mesenteric arterial bed (64) and in the human pulmonary artery (55). In this latter study, sensitivity to Tes-induced vasodilation was much higher in endothelium-intact than in endothelium-denuded vessels (1 nM vs. 30 μM; Ref. 55). Clearly, these data suggest the presence of an endothelium-dependent mechanism at physiological concentrations of Tes (11–36 nmol/l). This possibility is supported by previous in vivo studies that demonstrated that Tes-induced vasodilation of both canine coronary and porcine systemic arteries was nitric oxide (NO) dependent (3, 39). The simplest explanation of this discrepancy is that the vasorelaxation induced by lower physiological concentrations of Tes appears to be, at least in part, endothelium dependent, whereas vasorelaxation induced by higher pharmacological concentrations of Tes (>10 μM) in many in vitro studies appears to be endothelium independent. An alternate explanation is that Tes-induced vasorelaxation, while NO dependent, may rely on the activation of neuronal NOS in VSM cells. This possibility is supported by studies that employed nonselective NOS inhibitors such as NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester and by more recent studies which clearly established that lower physiological concentrations of Tes activate the formation of NO in VSM cells isolated from porcine coronary and rat mesenteric arterioles (8, 68).

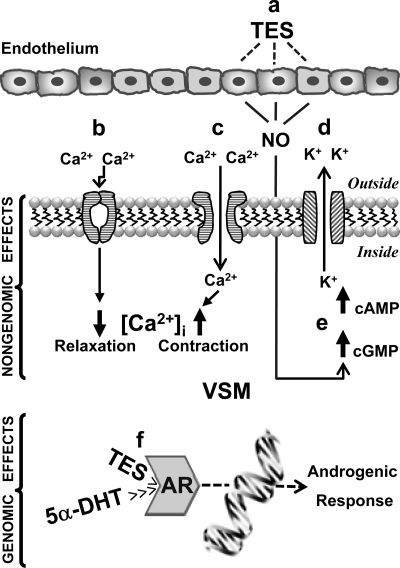

Structure-function studies employing a variety of Tes analogs and metabolites have revealed that Tes-induced vasodilation is a structurally specific nongenomic effect that is fundamentally different than the genomic effects of Tes on reproductive targets (10, 51, 73). Figure 1 summarizes the possible nongenomic mechanisms of androgen action on the vascular wall. A variety of studies has demonstrated that the key mechanism underlying the vasorelaxing action of Tes is associated with the modulation of VSM cell membrane ion channel function, particularly 1) inactivation of L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCCs) (6, 13, 17, 23, 24, 41–43, 48, 50, 59) or 2) activation of K+ channels (2, 3, 8, 10, 19, 60, 64, 68, 71, 73), particularly the voltage-operated K+ channel (Kv) and/or the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (BKCa).

Fig. 1.

Genomic and nongenomic mechanisms of action of androgens in the vascular smooth muscle (VSM) cell. a: Endothelium-dependent mechanisms, presumably involving endothelium-derived relaxing factors, particularly nitric oxide (NO), would seem to be responsible for the relaxing effect of testosterone (Tes) at physiological (<100 nM) but not at supraphysiological or pharmacological (>100 nM) concentrations. The incremental increase in cGMP reflects NO production, which induces vasorelaxation. Likewise, Tes and its metabolite 5β-dihydrotestosterone (5β-DHT) at pharmacological concentrations (>10 μM) induce endothelium-independent relaxation. b: Tes shares the same molecular target as the dihydropyridines [the α1C-subunit of L-type Ca2+ channels; voltage-operated Ca2+ channel (VOCC)] to elicit a powerful and direct channel blockade at physiological concentrations (36 nM) (17, 58, 59), restricting extracellular Ca2+ entry and diminishing intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in the VSM cell to induce vasodilation (relaxation). 5β-DHT, a much weaker androgen than Tes, is a pure VOCC blocker at a broad range of concentrations (from nanomolar to micromolar) (41). c: Tes but not 5β-DHT, at pharmacological concentrations (above 1 μM), activates VOCCs, increasing extracellular Ca2+ entry and increasing [Ca2+]i to induce vasoconstriction (contraction) (41). d: Tes at supraphysiological concentrations (>100 nM) activates voltage-operated K+ channels or large-conductance Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels, increasing K+ efflux to induce VSM hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation (8). e: Tes but not 5β-DHT at pharmacological concentrations (>30 μM) is capable of increasing cGMP and cAMP production (8, 41). f: Genomic actions of Tes and 5α-DHT are mediated by the cytosolic androgen receptor (AR). 5α-DHT has the highest affinity for the AR and mediates many androgenic effects, whereas 5β-DHT has little affinity and is without biological effects (14).

The direct vasorelaxing effect of Tes on VSM cells has also been examined in electrophysiological experiments using the patch-clamp technique, which have confirmed the findings from vascular function studies, i.e., that Tes inactivates VOCCs and/or activates Kv and BKCa. At physiological concentrations (11–36 nmol/l), Tes inhibits VOCC currents in rat A7r5 VSM cells and human embryonic kidney-293 cells (17, 58, 59); these studies also demonstrated that Tes and nifedipine share common molecular requirements for the inhibition of VOCCs (same site of action as dihydropyridines). Although VOCC function may differ in cultured cell lines, the results in primary cultured and freshly dissociated rat aortic myocytes (41) are consistent with the findings of these reports. At physiological to supraphysiological concentrations (10 nM-1 μM), Tes exhibits a greater potency than nifedipine to inhibit VOCCs, whereas at pharmacological concentrations (above 1 μM), the antagonist action of Tes on VOCCs is reversed to an agonist effect, increasing inward Ca2+ currents carried by VOCCs (41); this evidence may explain the vasoconstrictor effect of Tes observed by other investigators (18, 36, 57, 63). Furthermore, the authors (41) presented data revealing that the vasodilatory action of the 5β-reduced metabolite of Tes, 5β-DHT, involves the inhibition of VOCCs from nanomolar to micromolar concentrations (100 nM–32 μM). In addition, the agonist action of Tes to activate K+ channels at nanomolar concentrations has also been reported in patch-clamp studies. In porcine coronary myocytes, 200 nM Tes very dramatically activated BKCa channels, increasing the open probability by more than 10-fold (8). Similarly, in rat mesenteric myocytes, 100 nM Tes markedly activated Kv channels (68). In both studies, the selective blockade of BKCa or Kv channels markedly inhibited Tes-induced increases in K+ channel function.

Several additional mechanisms may also contribute to the Tes-induced relaxation of VSM at pharmacological (micromolar) concentrations in isolated blood vessels. Thus Tes can inhibit T-type Ca2+ currents (17, 59), as well as non-L-type VOCCs such as receptor-operated Ca2+ channels (6, 42, 50) and store-operated Ca2+ channels (24). Moreover, Tes may also cause vasorelaxation by modulating intracellular signal transduction pathways such as increasing the levels of cGMP (8) and cAMP (41), which may indeed evoke vasorelaxation. First, in VSM cells, Tes stimulates NO production (via neuronal NOS), which in turn evokes the formation of cGMP (via guanylyl cyclase) to induce vasorelaxation (8, 68). It has been reported that Tes increases cGMP accumulation and stimulates BKCa channel activity at micromolar concentrations (10–50 μM) in porcine coronary artery and at nanomolar concentrations (100 nM) in rat mesenteric myocytes to induce vasorelaxation (8, 68). Second, the modulation of intracellular cAMP by Tes may occur via the sex hormone-binding globulin-Tes complex and may be biologically active via its binding to cell-surface sex hormone-binding globulin receptors that evoke an increase in intracellular cAMP. Thus Tes (120 μM) stimulates cAMP production in single rat aortic myocytes (41); then, the activation of cAMP induces the phosphorylation of protein kinase A and subsequently protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of either phospholamban (a protein that inhibits the sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPase Ca2+ pump), phospholipase C (enzyme responsible for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production), or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, all of which are putative mechanisms of cAMP action.

An unequivocal determination whether androgens inactivate VOCCs or activate K+ channels is not possible at the present time, since most of the available studies have only explored one but not both of these possible mechanisms. Indeed, androgens may both inactivate inward Ca2+ currents carried by VOCCs (at physiological concentrations, 11–36 nM) and/or activate outward K+ currents carried by K+ channels (at physiological concentrations, 1–100 nM) in the VSM cell at different concentrations; however, a definitive answer will require more comprehensive studies that examine the roles of both mechanisms simultaneously. In the meantime, the reader is referred to a review that has examined this controversy in detail (25).

Structure-Function Relationship of Androgen-Induced Vasodilation

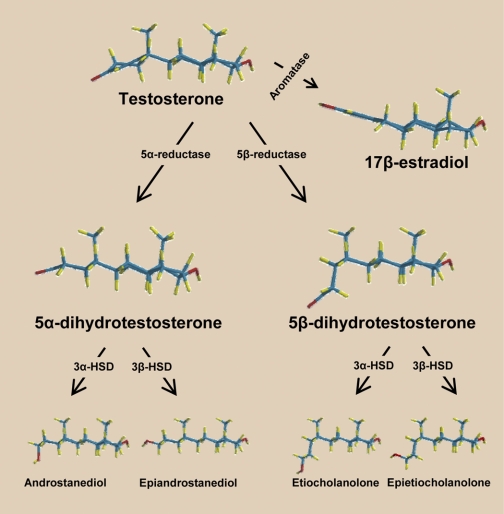

Since 17β-estradiol causes acute and long-term vasodilation and Tes and estrogens share the same biosynthetic pathway, it has been suggested that Tes-induced vasorelaxation might be an indirect effect mediated by the local conversion of Tes to 17β-estradiol by vascular P-450 aromatase (see Fig. 2). However, this possibility has been excluded for several reasons, 1) inhibition of P-450 aromatase does not prevent Tes-induced vasorelaxation (8, 63, 64, 73), 2) estrogen receptor antagonism does not alter Tes-induced vasodilation (3, 22, 48), and 3) nonaromatizable metabolites of Tes (e.g., DHT) cause vasorelaxation (8, 10, 47, 48).

Fig. 2.

Metabolic pathways of androgens. Tes can be bioconverted into 17β-estradiol via the enzyme P-450-aromatase or into its immediate 5-reduced dihydro-metabolites: 5α-DHT (via the enzyme 5α-reductase) and 5β-DHT (via the enzyme 5-β-reductase). Subsequently, these dihydro-androgens undergo a 3α- or 3β-hydroxylation via the enzymes 3α- or 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) to produce the tetrahydro-androgens (3α,5α-; 3β,5α-; 3α,5β-; and 3β,5β-reduced metabolites). Note the 3-dimensional conformation of the androgen molecules: Δ4,3-keto structure (Tes), 5α/trans-conformation (5α-reduced metabolites), and 5β/cis-conformation (5β-reduced metabolites). These molecular conformations reveal that minor changes in the orientation of C5 in the A-ring can result in major changes in the efficacy and potency of nongenomic vascular effects of the androgen molecule (e.g., 5α-DHT vs. 5β-DHT; see text for details).

Interestingly, it has been observed that Tes (>10 μM) acts as a pulmonary vasodilator with much greater efficacy than 17β-estradiol (12). Moreover, the Tes metabolite 5β-DHT is also more potent than 17β-estradiol in producing relaxation of the rat aorta (50), and both Tes and 5β-DHT are more effective than 17β-estradiol in blocking inward Ca2+ currents in rat aortic myocytes (41). These findings raise the possibility that androgens are more efficacious than estrogens in inducing vascular relaxation.

The metabolism of Tes in various target tissues yields a number of interesting compounds with potential biological relevance (Fig. 2). Apart from its irreversible bioconversion to 17β-estradiol via the enzyme aromatase (CYP19), Tes can also be converted to the 5-reduced dihydro-metabolites (5α and 5β reductions; Ref. 65), which include 5α-DHT via the enzyme 5α-reductase type 1 and 2 (56) and 5β-DHT via the enzyme 5β-reductase, a member of AKR superfamily (9). In this important metabolic pathway, it is emphasized that different tissues appear to have different relative activities of 5α- or 5β-reductase, resulting in different patterns of Tes metabolism, although it has been hypothesized that the 5α-reductase pathway has greater importance overall. These dihydro-metabolites subsequently undergo a 3α- or 3β-hydroxylation (via the enzymes 3α- or 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, respectively) to produce the tetrahydro-metabolites: 3α,5α-; 3β,5α-; 3α,5β-; and 3β,5β-reduced metabolites (androstanediol, epiandrostanediol, etiocholanolone, and epietiocholanolone, respectively). Androstanediol (a 3α,5α-androgen) via 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase is then converted into androsterone, a major excretory metabolite of Tes, and both androstanediol and androsterone are genomically inactive in reproductive targets.

It is important to emphasize that the dihydro- and tetrahydro-androgens are nonaromatizable; thus, they cannot be bioconverted into estrogens (Fig. 2). Since several recent studies have revealed that these nonaromatizable metabolites are fully capable of causing vascular relaxation (8, 10, 47, 48, 50, 73), the established concept that Tes is metabolized to inactive excretory metabolites must then be discarded when considering the effects of androgens on cardiovascular function. As a nonaromatizable dihydro-androgen metabolite of Tes, 5α-DHT has been frequently used as a tool to verify that the aromatization of Tes to estrogen is not required for this androgen to produce vasorelaxation (3, 8, 10, 64, 73). It has been reported that 5α-DHT exhibits a lower efficacy and/or potency than Tes to produce vasorelaxation in the rat aorta (10), pig coronary artery (8), and human umbilical artery (48). In marked contrast, the isomer of 5α-DHT, 5β-DHT, is notably more potent than Tes in the rat aorta and human umbilical artery (41, 47, 48). Whereas the circulating plasma concentration of Tes in adult men ranges 11–36 nmol/l, its 5α-reduced metabolite (5α-DHT) is present in the plasma at levels of only about 10% that of Tes (1.0–2.9 nmol/l). It is reasonable to suppose that the plasma levels of the 5β-reduced metabolite (5β-DHT) might be as low as its 5α-isomer. However, to our knowledge, there is no information available on the plasma concentrations of 5β-DHT; consequently, further research is urgently needed to determine the range of normal plasma concentrations of 5β-DHT. It is also important to recognize that the levels of 5α- and 5β-DHT in androgen target tissues that express 5α- and 5β-reductase are likely to be much higher than circulating plasma concentrations, which suggests that these metabolites act mainly as intracrine mediators in the androgen target tissues in which they are formed. For example, in the prostate gland, tissue 5α-DHT concentrations are 10-fold higher than in plasma. Thus the same may be true in the vascular wall.

With regard to the tetrahydro-androgens, the limited number of studies on their vascular effects has resulted in conflicting findings. Thus, depending on the vascular bed and species, these androgens are reported to be less efficacious and less potent or equipotent than Tes (10, 48, 73), whereas the Tes precursor dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and the Tes excretory metabolite androsterone may be more potent than Tes (48). Although most studies have established that DHEA does produce vasorelaxation, a contradictory vasoconstrictor response has been observed in prepuberal anesthetized pigs (40), which may be due to the different experimental conditions such as in vitro versus in vivo models, the use of adult versus prepubertal animals, the vascular effects produced by anesthetic agents, or the reflex responses activated by a systemic infusion of DHEA.

Nevertheless, the dramatic difference in vasorelaxing potency between Tes and its dihydro-metabolites deserves further consideration, based on their different structural conformations. We have observed that the A-ring of the steroid nucleus is planar in the structure of Tes and in the α/trans configuration at C5 of reduced metabolites such as 5α-DHT. In contrast, the A-ring bends 90° relative to the steroid nucleus when the C5 hydrogen is β/cis oriented, as in the case of 5β-reduced androgens such as 5β-DHT (see structural conformations in Fig. 2). Clearly, the structural change of the 5β configuration is critical for enhanced vasorelaxation efficacy as previously reported (41, 46–48). To avoid confusion, it must be recognized that Tes and its metabolites are clearly distinguishable by their fundamentally different configurations (Fig. 2). Isomerization may play an important role in this respect: molecules with the same chemical composition but with different spatial orientation of their substituents at critical points (e.g., at C5) may have totally different binding properties and biological effects. Thus 5α-DHT is a potent androgen with a strong affinity for the intracellular androgen receptor (AR), whereas its 5β-isomer (5β-DHT), which does not bind to the AR, is totally devoid of androgenic properties but is highly efficacious in producing vasorelaxation. Isomerization can therefore lead either to an inactivation or to a change in the specific biological properties of the original molecule.

Based on the aforementioned data, it is important to emphasize the high vasodilatory efficacy and potency of 5β-DHT, which are notably greater than those of Tes and its 5α-isomer (5α-DHT) in VSM as well as uterine smooth muscle (46, 48–50). Since 5β-DHT has little or no affinity for the intracellular AR and is totally devoid of androgenic properties (14), then the acute vasorelaxing effect of 5β-DHT is most likely mediated by an AR-independent, nongenomic mechanism. This line of evidence unequivocally establishes that the marked vasorelaxing effect of 5β-DHT is mediated through a nongenomic mechanism. In contrast, 5α-DHT possesses a high affinity for the AR and, hence, high androgenic activity (14). This metabolite is a powerful androgen at the genomic level, with higher potency than even Tes, but its nongenomic vasorelaxing efficacy and potency are notably less than those of Tes (8, 10, 48). On this basis, it is tempting to suggest that the two dihydro-metabolites of Tes elicit different biological responses: 5α-DHT with high genomic-androgenic action and 5β-DHT with high nongenomic-vasorelaxing action. For this reason, the 5β-reduced C19 steroids and/or functional 5β-DHT analogs, which do not exert estrogenic or androgenic effects, could have useful roles in vascular therapeutics.

Physiological Relevance

Because of the methodological limitations inherent to in vitro approaches, the ability of androgens to induce vasorelaxation of isolated blood vessels in most studies appears to be a pharmacological effect that occurs at high (micromolar) concentrations; hence, it is critical to consider whether this rapid, nongenomic effect of androgens has physiological relevance. While previous studies identified the potential of androgens to elicit vasorelaxation at pharmacological concentrations, more recent studies on the mechanism(s) of action at near physiological (11–36 nmol/l) concentrations strongly suggest that Tes-induced vasorelaxation is a physiologically relevant phenomenon (55, 64, 68). This suggestion is supported by clinical observations that Tes replacement in hypogonadal men reduces diastolic blood pressure (4, 33, 62, 70) and that serum Tes levels are reduced in both hypertensive men and women (20, 28, 52, 61).

If androgen-induced vasorelaxation reflects the ability of male sex hormones to modulate blood pressure, then physiological Tes replacement therapy in hypogonadal men may be beneficial in the regulation of blood pressure. In this regard, it is reported that serum concentrations of all Tes components decline as adult men age; likewise, plasma Tes levels are consistently lower in men with CVD (reviewed by Liu et al.; Ref. 31). However, little is known about age-dependent changes in Tes metabolites. It has been documented that serum 5α-DHT levels decline in men at the age of 50–70 years, whereas in women this hormone exhibits a progressive decline between the age ranges of 20–30 and 70–80 years (29); however, it is unclear whether possible reductions in 5β-DHT levels are related to pathophysiological changes with CVD. Notably, the endogenous Tes metabolite 5β-DHT is an efficacious and potent vasorelaxant that acts at nanomolar to micromolar concentrations without estrogenic and androgenic side effects, thus increasing its potential for use in the treatment of HT. In support of this view, 5β-DHT produces vasodepressor responses in pithed rats in vivo (51) and the activity of 5β-reductase, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of Tes to 5β-DHT, is significantly lower in essential hypertensive patients compared with their normotensive controls (21). In this context, it is suggested that 5β-reduced androgens (such as 5β-DHT) may play an important role in blood pressure regulation by reducing vascular tone; thus, reduced levels of 5β-reduced steroids may result in increases in vascular tone, contributing to the development of HT. This suggestion is supported by numerous clinical observations that androgen deficiency appears to exacerbate many risk factors and pathologies associated with CVD (66); however, the use of exogenous androgen therapy with Tes potentially may be linked to an increased risk of prostatic carcinoma (15, 45). Pharmacological blockade of the AR is a well-recognized treatment option for prostatic carcinoma, and this approach would still allow for the potential use of 5β-DHT as a safe, nongenomic treatment for patients with CVD.

Androgen-induced vasorelaxation of the human umbilical artery (48) is another potential physiological role for the vascular effects of androgens, which could contribute to the regulation of fetoplacental blood flow, one of the most important rate-limiting factors for normal fetal growth. Indeed, the vasorelaxing capability of Tes and its 5-reduced metabolites, particularly 5β-DHT (48), which are produced in the materno-fetoplacental unit (1), may be physiologically relevant in maintaining a sustained vasodilation in the fetoplacental circulation. This suggestion is consistent with previous findings showing markedly increased plasma levels of DHEA, androstenedione, and Tes throughout pregnancy (16, 35). Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that 1) an insufficiency of androgens during pregnancy, particularly 5β-DHT, could contribute, at least in part, to the development of preeclampsia/eclampsia and 2) exogenously administered 5β-DHT may be therapeutically relevant for the treatment of gestational HT. Not only does Tes induce similar vasorelaxation in isolated vessels from women (2, 48, 55, 71), but the female vasculature is also acutely sensitive to AR-independent vasodilation induced by 5β-DHT (48), which also increases its potential for use as a safe antihypertensive in women.

Finally, it is well known that the serum levels of Tes fall markedly with increasing age in otherwise normal men, and there is increasing evidence that Tes replacement therapy significantly improves cardiovascular and metabolic functions in hypogonadal aging men (28, 33, 34, 53, 62). Thus androgen replacement therapy with vasoselective androgens such as 5β-DHT, which exert little or no action on the AR receptor, may be an emerging therapeutic option for aging men to prevent vascular dysfunction such as HT, erectile dysfunction, and prostatic ischemia. Although these nongenomic actions may be subject to tachyphylaxis, there are insufficient data at present to unequivocally address this speculation. Indeed, the recent development of selective AR modulators (SARMs) may permit the selective treatment of CVD and the avoidance of androgenic side effects (7, 72) in fulfillment of the proposed clinical applications of androgen therapy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-080402 (to J. N. Stallone) and Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Inovación Tecnológica/Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico Grant IN202507-3 (to M. Perusquía) and a grant from the Programa de Apoyos para la Superación del Personal Académico de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to M. Perusquía while on sabbatical leave in the Department of Veterinary Physiology and Pharmacology at the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Benagiano G, Mancuso S, Mancuso FP, Wiqvist N, Diczfalusy E. Studies on the metabolism of C-19 steroids in the human foeto-placental unit. 3. Dehydrogenation and reduction products formed by previable foetuses with androstenedione and testosterone. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 57: 187–207, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairraö E, Alvarez E, Santos-Silva AJ, Verde I. Potassium channels are involved in testosterone-induced vasorelaxation of human umbilical artery. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 376: 375–383, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou TM, Sudhir K, Hutchison SJ, Ko E, Amidon TM, Collins P, Chatterjee K. Testosterone induces dilation of canine coronary conductance and resistance arteries in vivo. Circulation 94: 2614–2619, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corona G, Mannucci E, Lotti F, Fisher AD, Bandini E, Balercia G, Forti G, Maggi M. Pulse pressure, an index of arterial stiffness, is associated with androgen deficiency and impaired penile blood flow in men with ED. J Sex Med 6: 285–293, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costarella CE, Stallone JN, Rutecki GW, Whittier FC. Testosterone causes direct relaxation of rat thoracic aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277: 34–39, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crews JK, Khalil RA. Antagonistic effects of 17 beta-estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone on Ca2+ entry mechanisms of coronary vasoconstriction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 1034–1040, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton JT, Mukherjee A, Zhu Z, Kirkovsky L, Miller DD. Discovery of nonsteroidal androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 244: 1–4, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deenadayalu VP, White RE, Stallone JN, Gao X, Garcia AJ. Testosterone relaxes coronary arteries by opening the large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1720–H1727, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Costanzo L, Drury JE, Christianson DW, Penning TM. Structure and catalytic mechanism of human steroid 5beta-reductase (AKR1D1). Mol Cell Endocrinol 301: 191–198, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding AQ, Stallone JN. Testosterone-induced relaxation of rat aorta is androgen structure specific and involves K+ channel activation. J Appl Physiol 91: 2742–2750, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English KM, Jones RD, Channer KS, Jones TH. The coronary vasodilatory effect of testosterone is mediated at the cell membrane, not by an intracellular receptor (Abstract). J Endocrinol 164: 296, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 12.English KM, Jones RD, Jones TH, Morice AH, Channer KS. Gender differences in the vasomotor effects of different steroid hormones in rat pulmonary and coronary arteries. Horm Metab Res 33: 645–652, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.English KM, Jones RD, Jones TH, Morice AH, Channer KS. Testosterone acts as a coronary vasodilator by a calcium antagonistic action. J Endocrinol Invest 25: 455–458, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang H, Tong W, Branham WS, Moland CL, Dial SL, Hong H, Xie Q, Perkins R, Owens W, Sheehan DM. Study of 202 natural, synthetic, and environmental chemicals for binding to the androgen receptor. Chem Res Toxicol 16: 1338–1358, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 88: 1118–1126, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gant NF, Hutchinson HT, Siiteri PK, MacDonald PC. Study of the metabolic clearance rate of dehydroisoandrosterone sulfate in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 111: 555–563, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall J, Jones RD, Jones TH, Channer KS, Peers C. Selective inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels in A7r5 cells by physiological levels of testosterone. Endocrinology 147: 2675–2680, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman SM, Robinson JT, McCredie RJ, Adams MR, Boyer MJ, Celermajer DS. Androgen deprivation is associated with enhanced endothelium-dependent dilatation in adult men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 2004–2009, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honda H, Unemoto T, Kogo H. Different mechanisms for testosterone-induced relaxation of aorta between normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 34: 1232–1236, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes GS, Mathur RS, Margolius HS. Sex steroid hormones are altered in essential hypertension. J Hypertens 7: 181–187, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iki K, Miyamori I, Hatakeyama H, Yoneda T, Takeda Y, Takeda R, Dai QL. The activities of 5 beta-reductase and 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in essential hypertension. Steroids 59: 656–660, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones RD, English KM, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone-induced coronary vasodilatation occurs via a non-genomic mechanism: evidence of a direct calcium antagonism action. Clin Sci (Lond) 107: 149–158, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones RD, English KM, Pugh PJ, Morice AH, Jones TH, Channer KS. Pulmonary vasodilatory action of testosterone: evidence of a calcium antagonistic action. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 39: 814–823, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones RD, Pugh PJ, Hall J, Channer KS, Jones TH. Altered circulating hormone levels, endothelial function and vascular reactivity in the testicular feminised mouse. Eur J Endocrinol 148: 111–120, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RD, Pugh PJ, Jones TH, Channer KS. The vasodilatory action of testosterone: a potassium-channel opening or a calcium antagonistic action? Br J Pharmacol 138: 733–744, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalin MF, Zumoff B. Sex hormones and coronary disease: a review of the clinical studies. Steroids 55: 330–352, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kannel WB, Thom TJ. Incidence, prevalence and mortality and cardiovascular disease. In: The Heart, edited by Schlant RC, Alexander RW. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khaw KT, Barrett-Connor E. Blood pressure and endogenous testosterone in men: an inverse relationship. J Hypertens 6: 329–332, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labrie F, Bélanger A, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Candas B. Marked decline in serum concentrations of adrenal C19 sex steroid precursors and conjugated androgen metabolites during aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82: 2396–2402, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy D, Kannel WB. Cardiovascular risks: new insights from Framingham. Am Heart J 116: 266–272, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu PY, Death AK, Handelsman DJ. Androgens and cardiovascular disease. Endocr Rev 24: 313–340, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malkin CJ, Jones RD, Jones TH, Channer KS. Effect of testosterone on ex vivo vascular reactivity in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 111: 265–274, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mårin P, Holmäng S, Jönsson L, Sjöström L, Kvist H, Holm G, Lindstedt G, Bjorntoröp P. The effects of testosterone treatment on body composition and metabolism in middle-aged obese men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 16: 991–997, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mårin P, Lönn L, Andersson B, Odén B, Olbe L, Bengtsson BA, Björntorp P. Assimilation of triglycerides in subcutaneous and intraabdominal adipose tissues in vivo in men: effects of testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 1018–1022, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClamrock HD, Adashi EY. Gestational hyperandrogenism. Fertil Steril 57: 257–274, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCredie RJ, McCrohon JA, Turner L, Griffiths KA, Handelsman DJ, Celermajer DS. Vascular reactivity is impaired in genetic females taking high-dose androgens. J Am Coll Cardiol 32: 1331–1335, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendoza SG, Zerpa A, Carrasco H, Colmenares O, Rangel A, Gartside PS, Kashyap ML. Estradiol, testosterone, apolipoproteins, lipoprotein cholesterol, and lipolytic enzymes in men with premature myocardial infarction and angiographically assessed coronary occlusion. Artery 12: 1–23, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messerli FH, Garavaglia GE, Schmieder RE, Sundgaard-Riise K, Nunez BD, Amodeo C. Disparate cardiovascular findings in men and women with essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med 107: 158–161, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molinari C, Battaglia A, Grossini E, Mary DA, Vassanelli C, Vacca G. The effect of testosterone on regional blood flow in prepubertal anaesthetized pigs. J Physiol 543: 365–372, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molinari C, Battaglia A, Grossini E, Mary DA, Vassanelli C, Vacca G. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on regional blood flow in prepubertal anaesthetized pigs. J Physiol 557: 307–319, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montaño LM, Calixto E, Figueroa A, Flores-Soto E, Carbajal V, Perusquía M. Relaxation of androgens on rat thoracic aorta: testosterone concentration dependent agonist/antagonist L-type Ca2+ channel activity, and 5beta-dihydrotestosterone restricted to L-type Ca2+ channel blockade. Endocrinology 149: 2517–2526, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy JG, Khalil RA. Decreased [Ca2+]i during inhibition of coronary smooth muscle contraction by 17β-estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 291: 44–52, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Navarro-Dorado J, Orensanz LM, Recio P, Bustamante S, Benedito S, Martinez AC, Garcia-Sacristan A, Prieto D, Hernandez M. Mechanisms involved in testosterone-induced vasodilatation in pig prostatic small arteries. Life Sci 83: 569–573, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nettleship JE, Jones RD, Channer KS, Jones TH. Testosterone and coronary artery disease. Front Horm Res 37: 91–107, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parsons JK, Carter HB, Platz EA, Wright EJ, Landis P, Metter EJ. Serum testosterone and the risk of prostate cancer: potential implications for testosterone therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 2257–2260, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perusquía M. Androgen-induced vasorelaxation: a potential vascular protective effect. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 111: 55–59, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perusquía M, Hernández R, Morales MA, Campos MG, Villalón CM. Role of endothelium in the vasodilating effect of progestins and androgens on the rat thoracic aorta. Gen Pharmacol 27: 181–185, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perusquía M, Navarrete E, Gonzalez L, Villalón CM. The modulatory role of androgens and progestins in the induction of vasorelaxation in human umbilical artery. Life Sci 81: 993–1002, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perusquía M, Navarrete E, Jasso-Kamel J, Montaño LM. Androgens induce relaxation of contractile activity in pregnant human myometrium at term: a nongenomic action on L-type calcium channels. Biol Reprod 73: 214–221, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perusquía M, Villalón CM. Possible role of Ca2+ channels in the vasodilating effect of 5β-dihydrotestosterone in rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol 371: 169–178, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perusquía M, Villalón CM. The vasodepressor effect of androgens in pithed rats: potential role of calcium channels. Steroids 67: 1021–1028, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phillips GB, Jing TY, Resnick LM, Barbagallo M, Laragh JH, Sealey JE. Sex hormones and hemostatic risk factors for coronary heart disease in men with hypertension. J Hypertens 11: 699–702, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phillips GB, Pinkernell BH, Jing TY. The association of hypotestosteronemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 701–706, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reckelhoff JF, Zhang H, Granger JP. Testosterone exacerbates hypertension and reduces pressure-natriuresis in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 31: 435–439, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowell KO, Hall J, Pugh PJ, Jones TH, Channer KS, Jones RD. Testosterone acts as an efficacious vasodilator in isolated human pulmonary arteries and veins: evidence for a biphasic effect at physiological and supra-physiological concentrations. J Endocrinol Invest 32: 718–723, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russell DW, Wilson JD. Steroid 5α-reductase: two genes/two enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem 63: 25–61, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schrör K, Morinelli TA, Masuda A, Matsuda K, Mathur RS, Halushka PV. Testosterone treatment enhances thromboxane A2 mimetic induced coronary artery vasoconstriction in guinea pigs. Eur J Clin Invest 24, Suppl 1: 50–52, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scragg JL, Dallas ML, Peers C. Molecular requirements for L-type Ca2+ channel blockade by testosterone. Cell Calcium 42: 11–15, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scragg JL, Jones RD, Channer KS, Jones TH, Peers C. Testosterone is a potent inhibitor of L-type Ca2+ channels. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 318: 503–506, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seyrek M, Yildiz O, Ulusoy HB, Yildirim V. Testosterone relaxes isolated human radial artery by potassium channel opening action. J Pharm Sci 103: 309–316, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Svartberg J, von Muhlen D, Schirmer H, Barrett-Connor E, Sundfjord J, Jorde R. Association of endogenous testosterone with blood pressure and left ventricular mass in men. The Tromso Study. Eur J Endocrinol 150: 65–71, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tenover JS. Effects of testosterone supplementation in the aging male. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75: 1092–1098, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teoh H, Quan A, Leung SW, Man RY. Differential effects of 17β-estradiol and testosterone on the contractile responses of porcine coronary arteries. Br J Pharmacol 129: 1301–1308, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tep-areenan P, Kendall DA, Randall MD. Testosterone-induced vasorelaxation in the rat mesenteric arterial bed is mediated predominantly via potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol 135: 735–740, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomkins GM. Enzymatic mechanisms of hormone metabolism. I. Oxidation-reduction of the steroid nucleus. Recent Prog Horm Res 12: 125–133, 1956 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Traish AM, Guay A, Feeley R, Saad F. The dark side of testosterone deficiency: I. Metabolic syndrome and erectile dysfunction. J Androl 30: 10–22, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webb CM, McNeill JG, Hayward CS, de Zeigler D, Collins P. Effects of testosterone on coronary vasomotor regulation in men with coronary heart disease. Circulation 100: 1690–1696, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White RE, Owen MP, Stallone JN. Testosterone-induced vasorelaxation of rat mesenteric microvasculature is K+ channel- and nitric oxide-dependent but estrogen-independent (Abstract). FASEB J 21: 972.–10., 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu FCW, von Eckardstein A. Androgens and coronary artery disease. Endocr Rev 24: 183–217, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yaron M, Greenman Y, Rosenfeld JB, Izkhakov E, Limor R, Osher E, Shenkerman G, Tordjman K, Stern N. Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on arterial stiffness in older hypogonadal men. Eur J Endocrinol 160: 839–846, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yildiz O, Seyrek M, Gul H, Un I, Yildirim V, Ozal E, Uzun M, Bolu E. Testosterone relaxes human internal mammary artery in vitro. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 45: 580–585, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yin D, Gao W, Kearbey JD, Xu H, Chung K, He Y, Marhefka CA, Veverka KA, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Pharmacodynamics of selective androgen receptor modulators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304: 1334–1340, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yue P, Chatterjee K, Beale C, Poole-Wilson PA, Collins P. Testosterone relaxes rabbit coronary arteries and aorta. Circulation 91: 1154–1160, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]