Abstract

The production of verbal operants not previously taught is an important aspect of language productivity. For Skinner, new mands, tacts, and autoclitics result from the recombination of verbal operants. The relation between these mands, tacts, and autoclitics is what linguists call analogy, a grammatical pattern that serves as a foundation on which a speaker might emit new linguistic forms. Analogy appears in linguistics as a regularity principle that characterizes language and has been related to how languages change and also to creativity. The approaches of neogrammarians like Hermann Paul, as well as those of Jespersen and Bloomfield, appear to have influenced Skinner's understanding of verbal creativity. Generalization and stimulus equivalence are behavioral processes related to the generative grammatical behavior described in the analogy model. Linguistic forms and grammatical patterns described in analogy are part of the contingencies of reinforcement that produce generalization and stimulus equivalence. The analysis of verbal behavior needs linguistic analyses of the constituents of linguistic forms and their combination patterns.

Keywords: analogy, autoclitic, creativity, generalization, mand, neogrammarians, stimulus equivalence, tact, verbal behavior

Behavior analysts (Malott, 2003; Michael & Malott, 2003; Sundberg & Michael, 1983) and linguists (Anttila, 1989, p. 104; Coseriu, 1985, 2001, p. 21; Paul, 1886/1889, pp. xliii–xliv, 98–101) have considered the understanding of creative verbal behavior (or productivity) to be one of the most important areas of language study. This creativity is manifested in two ways: (a) as a speaker's behavior, in the production of verbal operants not previously taught, and (b) as a listener's behavior, as when acting adequately in the presence of verbal stimuli produced by a speaker, without a prior history to establish such verbalizations as discriminative stimuli that control the listener's behavior.

Although the analysis presented by Skinner in Verbal Behavior (1957) is frequently accused of being incapable of explaining creativity in general (Chomsky, 1959; Marr, 2003), it does address linguistic creativity (Place, 1985; Sundberg & Michael, 1983), mainly for the speaker, who is the primary focus throughout Skinner's analysis (Skinner, p. 2).

Skinner describes the emission of new mands, tacts, and autoclitics as the result of recombination of previously acquired verbal operants that share elements. In the mand, verbal responses of a given form, emitted under deprivation or aversive stimulation, are followed by a certain specific reinforcing consequence (Skinner, 1957, p. 35). A mand is called magical when it specifies a reinforcer that was never previously experienced by the speaker via a mand. Skinner assumes the existence of a kind of generic mand in the speaker's repertoire, which is independent of any particular instance of events that are “being manded.” In other words, it exists irrespective of any specific reinforcement. Or, in his own words,

The speaker appears to create new mands on the analogy [italics added] of old ones. Having effectively manded bread and butter, he goes on to mand the jam, even though he has never obtained jam before in this way. … The special relation between response and consequence exemplified by the mand establishes a general pattern of control over the environment. In moments of sufficient stress, the speaker simply describes the reinforcement appropriate to a given state of deprivation or aversive stimulation. The response must, of course, already be part of his verbal repertoire as some other type of verbal operant. … This sort of extended operant may be called a magical mand. (1957, p. 48)

The emission of a magical mand has as prerequisite the existence of: (a) a behavioral unit such as Please, pass the —, smaller than that directly reinforced, which emerged when such units as Please pass the bread and the butter were reinforced, and (b) a response with the appropriate form to specify the reinforcer (e.g., jam) acquired as another operant (Skinner, 1957, p. 48).

Skinner (1957) assumes also the existence of tacts that were created through analogy with tacts already present in the speaker's repertoire. The tact is a verbal operant under the control of non-verbal discriminative stimuli (pp. 81–82). Among the tacts of various sizes that constitute this repertoire, we find words, phrases, and sentences (pp. 119–120).

According to Skinner (1957), through the conditioning of bigger tact units (corresponding to the phrase or sentence), smaller tact units (corresponding to the word) will emerge: “Small functional units … also appear to emerge as by-products of the acquisition of larger responses containing identical elements” (p. 120). This is another example of the mechanism that would allow the emission of previously unreinforced verbal behavior, offering an account for part of what is usually called creativity in language. As it happens in the case of the mand, there is an emergence of units of verbal behavior, not reinforced directly, from the reinforcement of bigger units of verbal behavior that contain identical elements. The smaller units, after that, can be combined with other units that are already part of the speaker's repertoire.

The autoclitic frame also explains the emergence of creative verbal behavior. The autoclitic is a verbal operant under the control of discriminative stimuli provided by the speaker's own verbal behavior and its controlling variables (Skinner, 1957, pp. 311–343). Subjects studied by linguists, such as grammar and syntax (formal elements such as connectives, flexions, prepositions, the grouping and the ordering of verbal responses) have autoclitic functions (pp. 331–333). The autoclitic frame has empty spaces that are filled by verbal operants, which in turn are controlled by specific variables originating from a given situation. The model used by Skinner to propose the existence of these frames in the speaker's repertoire is the same that we already saw being adopted by him for the mand and the tact:

If he [the speaker] has acquired a series of responses such as the boy's gun, the boy's shoe, and the boy's hat, we may suppose that the partial frame the boy's … is available for recombination with other responses. The first time the boy acquires a bicycle, the speaker can compose a new unit the boy's bicycle. This is not simply the emission of two responses separately acquired. … The relational aspects of the situation strengthen a frame, and specific features of the situation strengthen the responses fitted into it. (p. 336)

The model for the emergence of mands, tacts, and autoclitic frames, proposed by Skinner, is what linguists call analogy.

ANALOGY IN THE TRADITION OF LINGUISTIC STUDIES

Analogy in Antiquity

Ever since classical antiquity, analogy has had an important role in linguistic explanations and descriptions of the practices of verbal communities. The postulation of analogy as a fundamental principle in linguistic studies began in Greek antiquity. Analogy is the same as Greek analogía, which meant mathematical proportion of four terms (e.g., a∶b = c∶d). This original usage in mathematics was extended to allow the study of linguistic issues, meaning “regularity” in this new field. Analogía was translated into Latin as proportio, ratio (Anttila, 1977, p. 25; Bynon, 1994; Elvira, 1998, pp. 7–8).

Thus, analogy appears as a basic principle of regularity in language. In ancient Greece, two different perspectives on language arose, which opposed anomalists and analogists. The anomalists, who were stoic philosophers, emphasized the role of irregularities in language. The analogists, best represented by Alexandrian grammarians, stressed the role of regularities in it. These regularities are mainly related to the same morphological termination found on words with the same grammatical function (e.g., in English, adverbs ending in –ly, such as happily, quickly, etc.), and to the relation between form and meaning, by which words with comparable morphological shape should also have comparable meanings (e.g., as in worked and danced, etc.; Robins, 1997, p. 26). The search for regularities in Greek was followed by Roman grammarians in their analysis of Latin, and continued to be applied to recent languages by grammarians who generally took the Greek and Latin grammatical analyses as their models (Malmkjær, 2002; Robins, pp. 60, 67).

Analogy was also used in ancient Greece in the critical editing of manuscripts (Taylor, 1995), especially in the emendation of Homeric texts. Scholars needed to establish criteria for choosing between different forms that appeared in different manuscripts, and analogy was an important one. Regular patterns (the ones followed by several forms) would be chosen instead of the irregular ones. Moreover, analogy was used to prescribe correct standards for linguistic forms. The ones related to a more regular paradigm were considered to be the most correct (Esper, 1973, p. 6; Robins, 1997, pp. 26, 37). However, the ancient grammarians also accepted that usage could bring irregularities to language (Esper, 1973, p. 5).

Already in antiquity, Varro (Rome, 116–27 BC) understood analogy as a mechanism that allows productivity in language, freeing speakers from the necessity of learning too many words: After learning how to inflect one name, the speaker will be able also to inflect other names (Esper, 1973, p. 9; Hovdhaugen, 1982, pp. 77–80).

Analogy in 19th Century Linguistics

Especially since Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), linguists understood analogy as a creative mechanism in language (Bynon, 1994). Humboldt conceived of language as a system of regularities for creation (Coseriu, 1992, p. 267; Paul, 1886/1889, p. 97). According to Coseriu (p. 22), in this context, “creador” [“creative”] means “que va más allá de lo aprendido” [“which goes beyond which was learned”].

Analogy was used by scientific linguistics as a mechanism that describes both a speaker's and a listener's creativity and provides an account of part of the changes that could be observed in a language over time. Scientific linguistics was born as an independent science, with its own methods of research, at the beginning of the 19th century. It was an historical and comparative linguistics, based on a comparative grammar of the Indo-European languages (Bloomfield, 1945/1970; Coseriu, 1980, p. 2; Davies, 1986). This historical and comparative trend did not prevent 19th century linguistics from making important statements on general linguistics. In the last quarter of the 19th century, a group of linguists who came to be called neogrammarians were at the center of the linguistic scene. Mostly located in Leipzig (B. I. Wheeler, 1889), they taught linguists whose works would come to mold structural linguistics, such as Courtenay, de Saussure, Sapir, and Bloomfield (Percival, 1973; Robins, 1997, pp. 210, 271). Contrary to the understanding of older linguists, they stated that linguistic sound change, the change in phonemes observed through the history of languages, is regular, with no place for exceptions (Davies, 1978; Robins, 1978).

Even though they have been accused of having an atomistic view of language and not paying attention to the need of synchronic description, quite a few historians of linguistics have denied these charges in more recent times (Bynon, 1978; Davies, 1986; Koerner, 1972) and have advocated a more positive view of their linguistics. In fact, the main lines of their teaching are still part of current linguistics (Bloomfield, 1932/1970; Coseriu, 1992, p. 25; Davies, 1978; Hoenigswald, 1978; Percival, 1973; Robins, 1978).

The neogrammarians anticipated important stands of structural linguistics, such us the prominence of the study of dialects (Esper, 1973, p. 26; Hoenigswald, 1978; Robins, 1978) as well as the use of living languages instead of examining written records only (Esper, p. 26; Percival, 1973; Robins, 1978); the distinction between speech and writing (Paul, 1886/1889, pp. 433–455; Robins, 1997, p. 210); the abstract character of the language as a reconstruction made by the linguist (Hoenigswald; Robins, 1978) as contrasted with the concrete production of individual speakers (Davies, 1978, 1986; Esper, p. 45; Jespersen, 1921, pp. 94–95; Percival; Robins, 1978); and analogy as responsible for the creative aspect of language (Anttila, 1977, p. 16; Davies, 1978; Vincent, 1974). They used analogy to furnish a mechanism that explains and links linguistic creativity and changes that a language presents over time.

Hermann Paul (1846–1921), one of the most important neogrammarians (Percival, 1973), published the influential Prinzipien der Sprachgeschichte in 1880. The second edition was greatly revised and translated into English as Principles of the History of Language in 1888 (Percival) and adapted to English in 1891 (Strong, Logeman, & Wheeler, 1891/1973). The book was seen by its contemporaries as the first clearly organized statement of the principles and methods of linguistic science, and as a successful effort to define it (Koerner, 1994; B. I. Wheeler, 1889). Percival stresses that the general view of language expressed in Paul's Principles is still important today. Since its publication and throughout the 20th century, this work was celebrated as “the fundamental handbook of the [linguistic] science” (B. I. Wheeler, p. vi), “a masterly book” (Jespersen, 1921, p. 95), “the standard work on the methods of historical linguistics” (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, p. 16), “magnífico” (Coseriu, 1992, p. 236), and the “bible” of the neogrammarians (Koerner, 1994). Paul was cited among five others scholars by de Saussure (1891/1954, p. 66) as someone who would advance knowledge about language and was considered to be “the only secure foundation” (Bolling, 1935/1970) until Bloomfield's Language appeared in 1933.

Koerner (1972, 1994) explored some aspects of Paul's (1886/1889) work that show his influence on de Saussure, anticipating focal trends of structural linguistics, such as the importance of the observation of speech (as opposed to written records), the core distinction between what would be later called synchronic and diachronic approaches to language, and the emphasis on descriptive work as a prerequisite to historical analysis. According to Esper (1973, p. 38), the experimental investigation of analogy started in 1901 inspired mostly by Paul's work on analogy.

As a linguist molded in the 19th century, Paul (1886/1889) focused on language change—how the current forms of the language could be understood as the result of modifications of older forms of that language. He understood that part of them, the sound changes, were due to what was called mechanical factors, to physiological changes that alter the way speakers pronounced the sounds. The other changes were mostly due to what was called a psychological mechanism (analogy) that he said was the creative aspect of language.

Paul (1886/1889) was aware of the abstract nature of the languages described by linguists. According to him, (a) languages are artifacts built by the methods of linguistic description, (b) the real and concrete fact on which this abstraction is based is the speech of the individual, and (c) it is this concrete production that we must look at if we want to understand the real activity of language (pp. 20–21). In spite of asserting the importance of abstractions in science, he warned against the possibility that abstractions could work as a veil that hides the real subject matter, which is the activity of the individual (pp. xxxiv–xxxv).

According to Paul (1886/1889), the speaker learns the language from others (pp. 22–23). While learning the native language, Paul contends that one does not learn rules, but just a series of examples. In this activity, he says, the speaker does not memorize everything; spoken language is not simply reproduced as heard. What one says is a composite of words and constructions previously heard and words and constructions freshly created in the moment. Instead of being chaotic, the mechanism of creation has the regularity of the functioning of the speaker's mind: It is analogy, based on the psychological activity of the speaker. Words and groups of words are created by means of a combinatory activity based on the existence of groups of ratios (or proportions) (pp. 97–105).

Grounded on Herbartian psychology, Paul (1886/1889) stated that heard and spoken words associate themselves in the speaker's mind, according to various kinds of links (pp. 4–6). The most important are the material and the formal groupings. Material groups are composed of words related through meaning, such as singular and plural forms of a noun, different tenses and modes of the same verb, and so on. In material groups, words in general share not just some content (the meaning) but also part of their sounds, because they are etymologically related. However, words within a material group may also be related by opposite meanings (e.g., boy∶girl; pp. 5–6, 92–110).

For Paul (1886/1889), formal groups involve relations among words and expressions that have similar functions in the sentence, such as same persons, same tenses, same modes of different verbs; strong past tenses of verbs; different substantives, adjectives, verbs, and so on (pp. 5–6, 92–93). There are also groups formed by words related by means of proportions. Paul calls them the material-formal proportion-groups, because a comparison is made based both on the signification of the material element and on the formal element. For instance, these words could form a proportion-group: lead∶leader∶leading = ride∶rider∶riding (pp. 93–109).

The phrases and sentences one hears that are framed in the same way are grouped together. The element they share is strengthened through repetition, and that is how one deduces “unconsciously” the rule from the examples (pp. 5–6, 95–99). The groups intersect each other, forming smaller subgroups inside the bigger ones. For example, there is a big formal group of the past tense of different verbs composed by verbs like took, walked, came, went, talked, brushed, and so on. There are also smaller subgroups inside this big one, such as the one composed of verbs that have regular past tense (walked, talked, brushed) and another composed of verbs with irregular past tense (took, came, went).

These associations, constituted and operating without consciousness in the speaker's production of speech, should not be confused with categories abstracted through the linguists' grammatical reflection (Paul, 1886/1889, pp. 5, 11–18, 41, 99). The groups so formed are the basis for the working of analogy. According to Paul,

Another hardly less important factor [in addition to reproduction by memory] is the combinatory activity based upon the existence of the proportion-groups. The combination consists to some extent in the solution of an equation between proportions, by the process of freely creating, for a word already familiar, on the model of proportions likewise familiar, a second proportional member. This process we call formation by analogy. (p. 97)

Creativity based on analogy can be clearly seen in word formation, inflection (pp. 101–102), and syntax (pp. 98–99).

Although in Paul's (1886/1889) writing we find many mentalist expressions among his explanations of linguistic behavior, they are only additions alongside other explanatory factors that he always presents and which are the ones which are interesting to the behavior analyst: linguistic forms and the positions they occupy in relation to each other in the sequence of speech. The factors that influence the formation and solidity of the groups are also objective, such as correspondence in meaning, the shape of the sounds, the frequency of occurrence of single words, and the number of possible analogous proportions (pp. 96–97, 101).

Among several linguists whose work on analogy and other issues were affected by Paul, we will be particularly interested in Jespersen and Bloomfield because of their influence on current linguistics and the apparent influence they had on Skinner's use of analogy.

Analogy in Otto Jespersen

The Danish linguist Otto Jespersen (1860–1943) contributed to many fields of linguistic inquiry, from the teaching of foreign languages to the study of several ancient and living languages; his study of the history and structure of the English language, for example, has been considered to be monumental (Bloomfield, 1922/1970; Falk, 1992). According to Falk, he was an independent linguist whose work cannot be situated in any specific trend or school into which historians are used to organizing the field of linguistics; his perspective showed both the historical approach characteristic of 19th century linguistics and the structural and descriptive one predominant in 20th century linguistics.

In his influential Language (1921), referred to twice by Skinner in Verbal Behavior (1957, pp. 13, 44), Jespersen stressed the concreteness of the individual speaker in contrast to the abstract and artificial character of the representation of the language as it appears in grammars and dictionaries. He pointed to the role of analogy for the understanding of language changes over time and a speaker's creativity (pp. 93–99). He attributed to the neogrammarians in general and to Paul in particular the growth of knowledge about these issues. It is worth reproducing part of his long quotation of Paul in connection with this matter, because we will encounter in this quote key positions adopted by Skinner in Verbal Behavior (1957).

While speaking, everyone is incessantly producing analogical forms. Reproduction by memory and new-formation by means of association are its two indispensable factors. It is a mistake to assume a language as given in grammar and dictionary, that is, the whole body of possible words and forms, as something concrete, and to forget that it is nothing but an abstraction devoid of reality, and that the actual language exists only in the individual, from whom it cannot be separated even in scientific investigation. … To comprehend the existence of each separate spoken form, … [we must ask] “Has he who has just employed it previously had it in his memory, or has he formed it himself for the first time, and, if so, according to what analogy?” (Paul, quoted in Jespersen, 1921, pp. 94–95)

Although Skinner, in his explanation of the emergence of new units of verbal behavior, does not mention Jespersen's treatment of analogy, we can posit that this could possibly have contributed to the shaping of Skinner's understanding of it. The approaches are compatible with respect to linguistic issues, and the example that Skinner offered (1957, p. 336) is reminiscent of one of Jespersen's (1921, p. 128): “by analogy with ‘Jack's hat’ and ‘father's hat’ the child invents such as ‘uncle's hat’ and ‘Charlie's hat.’”

Bloomfield's Description of Analogy

In Language (1933/1961), known by Skinner at least since 1934 (Skinner, 1979, p. 150; Epstein, Lanza, & Skinner, 1980), Bloomfield offers a clear description of analogy. In his account, Bloomfield specifies only elements that interest us behavior analysts, by virtue of the physicalism of his explicitly behavioristic position (Bloomfield, 1926/1970, 1930/1970, 1936/1970). According to Bloomfield (1933/1961, p. 275), an analogy is a grammatical pattern, a specific combination of forms, through which the speaker can emit linguistic forms not previously heard, provided that he or she knows the constituents of these forms and the grammatical pattern. A regular analogy relates a great number of forms in a language and therefore allows the speaker to emit many forms not heard by him before. According to Bloomfield, analogies are habits: “The regular analogies of a language are habits of substitution” (p. 276).

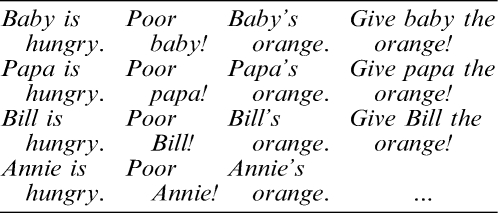

Bloomfield (1933/1961, pp. 275–276) shows how this habit works. He assumes a speaker who knows the following forms:

This speaker will have the habit of uttering the form Annie in the same positions as baby, papa, and Bill. When the appropriate occasion appears, the speaker will emit Give Annie the orange! Forms with similar functions (i.e., those that occupy the same positions in more inclusive forms like phrases and sentences; Bloomfield, 1943/1970) become associated as we also saw above in Skinner's examples.

Following the linguistic tradition outlined above, Bloomfield considers the emission of one form by means of analogy with other forms as equivalent to solving an equation by way of proportional ratios, in which there are a large number of known elements on several similar ratios (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, p. 276):

Baby is hungry : Annie is hungry

poor baby : poor Annie = Give baby the orange : x

baby's orange : Annie's orange

and

dog : dogs

pickle : pickles = radio : x

potato : potatoes

piano : pianos

Bloomfield (1933/1961) advises us that this is a model by which the linguist describes the speaker's behavior, which does not imply at all that the speaker him- or herself gives the same description of his or her behavior:

Psychologists sometimes object to this formula, on the ground that the speaker is not capable of the reasoning, which the proportional pattern implies. If this objection held good, linguists would be debarred from making almost any grammatical statement, since the normal speaker, who is not a linguist, does not describe his speech-habits, and, if we are foolish enough to ask him, fails utterly to make a correct formulation. …. The speaker, short of a highly specialized training, is incapable of describing his speech-habits. Our proportional formula of analogy …, like all other statements in linguistics, describes the action of the speaker and does not imply that the speaker himself could give a similar description. (p. 406)

ANALOGY AT PRESENT

According to Anttila (1977, pp. 2–5), in spite of the decline in the prestige of analogy as a concept in linguistics due to objections raised by generative grammar around 1960, in the 1970s the concept of analogy was rehabilitated back into the field. Analogy is still offered as a way to understand the creative doings that language allows humankind (Anttila, 1989, pp. 104–106; Bynon, 1994; Davies, 1978; Elvira, 1998, pp. 152–155; Esper, 1973, p. 201; Peabody, 1975, pp. 361, 364, 374–375, 384). The role of analogy as a mechanism for injecting regularity into language and thus making it easier to learn has also been stressed (Esper, p. 169).

The linguistic model of analogy has been widely employed, although sometimes without awareness of it, especially in the tradition of behavior analysis. Skinner's explicit criticism of linguistic analyses (1957, pp. 3–10; 1969, pp. 11–12; 1987, p. 92) endorsed the belief that they were not appropriate (Vargas, 1992, p. xiii), because they were fundamentally “prebehavioral” (Lee, 1984). Yet a different understanding could emerge from Skinner's work. He expressly acknowledged that his analysis of verbal behavior did not substitute for the work of linguistics, which cannot be avoided (Skinner, 1957, p. 44), and did not encompass an analysis of languages (Skinner, 1957, p. 461), the verbal environment from which verbal behavior develops. Even more important, according to Matos and Passos (2006), linguistic analyses were valuable tools for him to define verbal operants, which are a composite result of knowledge coming from two different fields. Skinner's model of the three-term contingency furnished the nature of the elements and their contingent relations, and linguistic presentations of the forms of the language, their meaning and function, indicated the forms that could be part of verbal operants and their possible controlling variables (Matos & Passos).

We are used to considering our language by means of the theoretical framework (categories like subject, predicate, verbs, adjectives) provided mainly by the traditional grammar that we learned in grammar school (Bloomfield, 1933/1961, pp. 3–8). We are unaware of the theoretical nature of this framework, and confuse it with the language itself. Skinner's criticisms of linguistic analyses and the lack of awareness of the analytical framework implied in grammatical analyses combined to turn invisible and unnoticed the pervasive presence of linguistic analyses in the studies of verbal behavior guided by behavior analysts. This happened to a considerable extent to the model of analogy.

Several behaviorists who worked on verbal behavior around the period of 1940 to 1960 employed and were aware of employing linguistic analyses in their work, and deliberately tried to find explanations for the verbal behavior of the individual implied in linguistic descriptions of languages. Jenkins and others considered (see Jenkins, 1965), as general linguists do (Auroux, 1994, pp. 111–112; Palmer, 1984, pp. 128–129), the rules of traditional grammar and linguistics, including the analogy model, as reporting observed regularities in the linguistic behavior found in a verbal community, and that the acquisition of these regularities required explanation by psychology.

According to Saporta (1959), linguistics (a) indicates how the particular system of a particular language may be one of the factors that control verbal responses and (b) suggests a framework for the analysis and classification of verbal responses. As stated by Jenkins (1965), the kinds of classes and organization found in the system of the language will be particularly useful for the analysis and description of verbal behavior. For Rosenberg and Koplin (1965), linguistics contributes through the “specification of manipulable dimensions of verbal materials and in the form of hypotheses about the functional units of language behavior” (p. 7).” As noted above, this interaction between linguistic and behavioral analyses can be found in Skinner's (1957) analysis of verbal behavior.

Even without being explicitly mentioned, and perhaps without awareness of its use as an analytical and classificatory tool, the analogy model may have inspired not just Skinner but also other authors who work in the analysis of verbal behavior. One important influence can be seen in the model of stimulus equivalence, which has flourished in behavior analysis since Sidman's fundamental work in the field (Sidman, 1994; see Urcuioli, 1996). Equivalence relations were first studied in research on verbal behavior outside the field of behavior analysis (Donahoe & Palmer, 2004, pp. 145, 151; Fields, Verhave, & Fath, 1984; Hayes, Blackledge, & Barnes-Holmes, 2001; Urcuioli), with Jenkins having a prominent role in these early efforts. The basic logic of Jenkins's and Sidman's work in equivalence is the same (Lazar, 1977), and how much the former inspired the latter can be gleaned from Sidman's frequent comments on the theoretical and methodological lines chosen by Jenkins.

By 1959, Jenkins had designed basic paradigms that were explored in his and in later experiments on equivalence relations. Several theoretical and methodological elements of his work were not employed in behavior-analytic research on equivalence relations, such as the S-R framework, mediated associations explaining the emergence of equivalence relations not directly taught, the pairing association techniques, and the experimental group design. However, several of them (Jenkins, 1959, 1963) remain influential, such as (a) the basic logic of the paradigms and the investigation of diverse possibilities of training and testing within them; (b) the several roles that the elements can play in each paradigm (stimulus or response in Jenkins's work, or the functions of model and comparison in Sidman's studies); (c) the acknowledgment of reverse chaining or backward association (symmetry in Sidman's studies) that results from the procedure; (d) the recognition that the method resulted in the learning of relations (through reverse chaining and transitivity) beyond the ones that were taught.

The analogy model inspired much of Jenkins's work. As early as 1954 Jenkins and Newmark (1954) already mentioned “use by analogy” as an assumption frequently made when describing language processes and suggested an investigation of it through an experimental analogue of language that allowed control of units and processes. In this direction, they thought it would be worth investigating whether the reinforcement of the use of two verbal units in a number of the same contexts and of the use of one of these units in a new context would lead to the use of the second unit in this new context. Jenkins explicitly mentions the link between analogy and his research on equivalence:

The writer's [himself] concern with the problem [mediated association] arises out of his concern with and research in psycholinguistics. In language learning it is customary for linguists and psychologists alike to appeal to “learning by analogy” to account for the development of form classes, sentence frames, morphemes indicating plurals, past tense, etc., etc. But one looks in vain for an explication of “learning by analogy,” or experimental evidence bearing on the process. Even such a confirmed stimulus–response “no-nonsense” investigator as Skinner (1957) appeals to this “principle” of explanation. Verbal behavior obviously demands some such process to explain similarity in form, pattern, and, especially, meaning. (1959, p. 2)

Evidently Jenkins did not consider analogy to be an explanation of behavior, but instead was something that required explanation. He was interested in the investigation of behavioral models that accounted for the regularities described in grammars, and sought how mediation models of equivalence could be part of a behavioral explanation of them. This includes analogy, which enables the emission and understanding of utterances not heard before (Jenkins, 1964, 1965). Analogy implies equivalence and a system of relations:

At the heart of analogy is equivalence of some sort. In the simplest form of analogy, two items are presented, bearing some relation or set of relations to each other. A third item is given and a fourth item must be generated (e.g., Fuzz is to peach as — is to fish). (Jenkins, 1965, p. 73)

According to Jenkins (1965), some errors made by children, like taked instead of took, inform the systematic nature of language and show that the form was created by analogy with other forms that belong to a same class. This kind of datum, as well as data gathered in research using paired associate techniques (Jenkins, 1954), convinced him of the behavioral validity of grammatical classes and the need to search for the processes that could explain their acquisition. The paradigms (Jenkins, 1963, 1964) through which equivalence among stimuli could develop were also the source of some hypotheses about the development of functional classes in verbal behavior that corresponded to grammatical classes. For example, Jenkins (1964) suggested that the pairing of elements (e.g., A-B, C-B, A-D, and C-D), would produce (a) the learning of more relations than the ones directly involved in the pairings, (b) a tendency for one to occasion the other (i.e., a sequence relation), and (c) two classes, one with the elements A and C and the other with B and D.

In a historical language, we would find a similar situation constituted by the sentences:

Baby cry

Johnny cry

Baby eat

Johnny eat

Baby and Johnny will be in one class and cry and eat in another one. If we have a new context in which one element of the latter class appears (e.g., Mary cry), we can expect the emergence of Mary eat (Jenkins, 1964).

From the learning of these sequences of words, Jenkins (1964) supposes the formation of two classes (one integrated by the words in the first position, the other one by the words in the second position) and the possibility of emission of new sequences that were not previously learned. Thus, in the acquisition of syntax, “class and sequence structure are learned simultaneously and interdependently” (Jenkins & Palermo, 1964, p. 164). Classes of words will be formed as soon as utterances with more than one word appear, with words in the same position in utterances constituting a class. The elements in a same class can substitute for one another in specific structural frames (Jenkins & Palermo). Jenkins (1965) was aware of the fragility of his explanation and mentioned the paucity of the demonstration of equivalence at that time, but even so he thought it was worth trying to use this model to understand linguistic behavior.

Jenkins's suggestion that the relative position of verbal stimuli in a sentence could build class membership was investigated by other researchers who worked on word association. Glucksberg and Cohen (1965) explored the acquisition of form class membership due to the forms having appeared in a same syntactic position. After being taught to utter nonsense syllables in noun or verb positions in a sentence, when these syllables appeared as stimuli in a free-association task, subjects responded with words that fell in the same grammatical class. Because previous research had shown the high probability that adults in a free-association task would answer with a word that belongs to the same grammatical class as the stimulus word (Jenkins, 1959, pp. 3–4, 1965), Glucksberg and Cohen concluded that the exposure to the nonsense syllables in a specific syntactic position (noun or verb) resulted in their classification by the subjects into the correspondent grammatical class.

In the field of behavior analysis, the model of analogy can be found in investigations of the productivity of language at the morphological and syntactic levels. Guess, Sailor, Rutherford, and Baer (1968) investigated the productive emission of the plural morpheme, and Schumaker and Sherman (1970) investigated the productive emission of verb inflection (present and past tense). From the training of a few exemplars, the subjects emitted new plural forms and present and past tense forms not directly taught. Guess et al. interpreted the results in terms of the training having built a generalized productive response class in the subjects' repertoires. A. J. Wheeler and Sulzer (1970) applied the same rationale to productive syntactic behavior, and interpreted their results in a similar way. When they taught a child to describe pictures with sentences having the form subject phrase + verb phrase + object phrase (e.g., “The man is smoking the pipe”), the child extended this form of sentence to describe pictures to which this sentence form had not been taught. In these three studies, only Schumaker and Sherman (p. 273) mentioned analogy (“analogic extension” and “building by analogy”), but they do not discuss the model itself or its linguistic origins.

Some recent research is a direct offspring of Skinner's (1957) analysis of productivity of mands, tacts, and autoclitics. In Hernandez, Hanley, Ingvarsson, and Tiger (2007), teaching of framed mands (e.g., “I want the cars, please”) led to generalization to untrained framed mands (e.g., “I want the books, please”). Hernandez et al. also interpreted their results in terms of generalized response classes.

Lazar (1977) represents a convergence of the studies on equivalence with those on analogy and grammar (syntax, in this case). Working with behavioral analogues of syntactic relations, he established (a) relations of order (first and second position) between pairs of stimuli, and (b) conditional relations between these stimuli and new stimuli through a matching-to-sample (MTS) procedure in which one new stimulus was the reinforced comparison in the presence of a “first” stimulus and another new stimulus was the reinforced choice in the presence of a “second” stimulus. Nontrained sequences emerged, with the new stimuli (that had not been trained for order) appearing in sequences that corresponded to the order trained for the stimuli trained for order. The emergence of the new sequences was interpreted as if the ordered relations trained for the pairs of stimuli transferred to all the stimuli of their respective classes established through MTS. Lazar and Kotlarchyk (1986) first established two equivalence classes through MTS, and then used one stimulus of each class in a sequence procedure relating the two stimuli in a first and second position. The position designated as correct for these two stimuli was conditional to a tone. When tested in the presence of each one of the tones, the subjects appropriately ordered the other members of the equivalence classes without having been trained to do so. The model of analogy is not mentioned in these two studies, but it is implied in the discussion of the extension of the experimental results to understand grammar. Lazar and Kotlarchyk explicitly reported that their motivation in unraveling aspects of equivalence classes was to make possible the understanding of linguistic performances. The conditional discrimination of the ordered stimulus was established to explore the fact described by linguists that the meaning of words is dependent on their context. Subsequent studies followed the path opened by Lazar and investigated additional variables involved in establishing equivalence and sequence classes of stimuli that are relevant for generative syntactic repertoires (e.g. Green, Sigurdardottir, & Saunders, 1991; Sigurdardottir, Green, & Saunders, 1990; Wulfert & Hayes, 1988).

The phenomena and processes investigated in relational frame theory (RFT) as analogical language, classical analogy, or analogical reasoning (Carpentier, Smeets, & Barnes-Holmes, 2002; Stewart, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2004; Stewart, Barnes-Holmes, Roche, & Smeets, 2001) are not the same as what linguists call analogy. The discussion by RFT authors of (a) Skinner's interpretation of analogy as metaphorical extension (Stewart et al., 2004); (b) analogical reasoning as referred to by philosophers, psychologists, and physicists (Carpentier, Smeets, Barnes-Holmes, & Stewart, 2004); and (c) their studies on analogical language as an example of research on higher cognition (Stewart & Barnes-Holmes, 2004) indicates that they are targeting behavior that presupposes a verbal repertoire of considerable extension and sophistication rather than basic features of an early repertoire. When explaining emergent verbal behavior involving the grammatical patterns called analogy by linguists, RFT authors (see, e.g., D. Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Cullinan, 2000; Y. Barnes-Holmes et al., 2001) refer to Wulfert and Hayes (1988), an extension of Lazar (1977) and Lazar and Kotlarchyk (1986).

Research on stimulus equivalence investigates behavioral processes that could explain what linguists call analogy. The contribution of the linguistic model of analogy to these studies on equivalence has been (a) to state the problem (the emergence of new linguistic behavior); (b) to analyze the linguistic forms (words, phrases and sentences); (c) to point to linguistic classes formed according to the relative position of linguistic forms in words, phrases, and sentences; and (d) to describe the grammatical patterns (the sequences) in which the linguistic forms can be arranged.

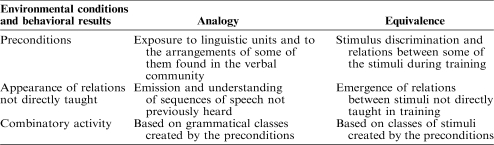

The linguistic model of analogy and the behavioral contingencies that generate equivalence are complementary descriptions of some aspects of language. It is not by chance that they share so many characteristics (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Analogy and stimulus equivalence

CONCLUSION

Skinner's (1957) description of the emergence of new mands, tacts, and autoclitics appears to be deeply rooted in the linguistic model of analogy. Although Jespersen's Language (1921) was one of his sources, it seems that Bloomfield's (1933/1961) description of analogy may have been his most direct model. If this is correct, then we can add the issue of analogy to the other influences of Bloomfield's work on important elements of Skinner's approach to verbal behavior (Joseph, Love, & Taylor, 2001, p. 110; Matos & Passos, 2006; Passos, 2007; Passos & Matos, 1998, 2007).

Through Jespersen (1921) and Bloomfield (1933/1961), we can also posit at least an indirect influence of Paul's (1886/1889) work on Skinner's (1957) Verbal Behavior. Both Bloomfield's Language and, particularly, Jespersen's Language referred to Paul with approval and offered a detailed description of important parts of his work. However, the possibility of a direct influence by Paul on Skinner's ideas would be worth investigating. First, during the period (1922 to 1926) in which Skinner (1976) received his major in English literature (Hamilton College, New York), Paul's Prinzipien was perhaps the most influential book in the field of linguistics. Its translation and adaptation to English, as well as the public commendations it received, indicate its impact on Anglo-American scholarship. Second, key aspects, as well as a few specific formulations, of Paul's and Skinner's approaches follow each other closely, as is outlined below.

The language described by linguists and grammarians is conceived as an abstraction, while the actual language is described as existing in the individual (Paul [quoted in Jespersen, 1921], pp. 94–95; Paul, 1886/1889, pp. xxxv, xliii, 2, 21; Skinner, 1957, pp. 4, 7, 13, 18).

The appearance of something new in the speaker's activity is viewed as the result of new combinations of old elements. According to Paul, in the linguistic activity of the individual, “the occasion for something new to arise is perpetually occurring, at least in the form of new variations of old elements” (1886/1889, p. 6). Similarly, for Skinner, “new forms of [verbal] behavior emerge from the recombination of old fragments” (Skinner, 1957, p. 10).

The metaphor of the “living language” is used to refer to the language as it is spoken by each individual rather than the language as analyzed by the grammarian or linguist. According to Paul (1886/1889), “The self-deception under which grammarians labour depends on their having regarded the word not as a portion of the living language—audible for a moment, and then passing away—but as something independent to be analyzed at leisure” (p. 37). For Skinner (1957), “The verbal operant is a lively unit, in contrast with the sign or symbol of the logician or the word or sentence of the linguist” (p. 312).

The spoken, and not the written, language was selected as the preferred reference in the study of verbal behavior (Paul, 1886/1889, pp. 37, 433–455; Skinner, pp. 14–19).

The speaker's linguistic activity is viewed as mainly automatic, involuntary, and unconscious (Paul, 1886/1889, pp. xliv, 4–6, 9, 37, 41, 98–99; Skinner, pp. 92, 186).

Language is considered to be learned (Paul, 1886/1889, pp. 15, 98–101; Skinner, 1957, pp. 203–219).

Analogy is taken to be a model that specifies linguistic forms and grammatical patterns involved in psychological or behavioral processes that describe creativity of language.

Progress in science is cumulative (Skinner, 1953, p. 11). The neogrammarians and their successors highlighted the linguistic activity of the individual speaker, but they did not create a unit of analysis of his or her behavior while they investigated the linguistic practices of the verbal community. Skinner likely benefited from their contributions. He used linguistic descriptions of these practices to understand part of the contingencies that give rise to the behavior of the individual speaker (Matos & Passos, 2006). At this point, we reach his unique and remarkable contribution to the field of language: to establish the verbal behavior of the individual speaker as the legitimate object of study of his science, and to provide the operant contingency as the model for its analysis. The operant contingency, together with the units furnished by linguistic analysis, enables us to build a repertoire of verbal behavior.

After Skinner, the model of analogy is still found in research in the field of behavior analysis, especially in research related to new verbal repertoires and the field of stimulus equivalence.

Acknowledgments

This paper is an enlarged version of one presented at the 30th annual convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis, Boston, 2004. The additional work required for its publication was postponed due to the illness of Maria Amelia Matos, who unfortunately died in 2005. The reader can find in McIlvane (2006) and Tomanari (2006) two sensitive descriptions of her life and work. I am grateful for having had her as a wonderful adviser and friend.

I thank William Dube for encouraging me to finish and submit this work even in Maria Amelia's absence. I also thank David Eckerman and Fátima Pires who, being very close to Maria Amelia both professionally and personally, agreed to read and comment on the final draft of the manuscript, which improved very much after their suggestions.

REFERENCES

- Anttila R. Analogy. The Hague: Mouton; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila R. Historical and comparative linguistics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Auroux S. La révolution technologique de la grammatisation: Introduction à l'histoire des sciences du langage [The technological revolution of grammatization: Introduction to the history of the language sciences] Liège: Mardaga; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Cullinan V. Relational frame theory and Skinner's Verbal Behavior: A possible synthesis. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Healy O, Lyddy F, Cullinan V, et al. Psychological development. In: Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. pp. 157–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1961. (Original work published 1933) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language: Its nature, development and origin by Otto Jespersen. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 102–105. (Reprinted from American Journal of Philology, 43, 370–373, 1922) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. A set of postulates for the science of language. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 128–138. (Reprinted from Language, 2, 153–164, 1926) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Linguistics as a science. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 227–230. (Reprinted from Studies in Philology, 27, 553–557, 1930) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Lautgesetz und Analogie by Eduard Hermann. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 240–251. (Reprinted from, Language, 8, 220–232, 1932) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Language or ideas? In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 322–328. (Reprinted from Language, 12, 89–95, 1936) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. Meaning. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 400–405. (Reprinted from Monatshefte für Deutschen Unterricht, 35, 101–106, 1943) [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield L. About foreign language teaching. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 426–438. (Reprinted from The Yale Review, 34, 625–641, 1945) [Google Scholar]

- Bolling G.M. Language by L. Bloomfield. [Review]. In: Hockett C.F, editor. A Leonard Bloomfield anthology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1970. pp. 277–278. (Reprinted from Language, 11, 251–252, 1935) [Google Scholar]

- Bynon T. The neogrammarians and their successors. Transactions of the Philological Society. 1978:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bynon T. Analogy. In: Asher R.E, Simpson J.M.Y, editors. The encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford, UK: Pergamon; 1994. (Vol. 1, pp. 110–111). [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier F, Smeets P.M, Barnes-Holmes D. Matching functionally same relations: Implications for equivalence-equivalence as a model for analogical reasoning. The Psychological Record. 2002;52:351–370. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier F, Smeets P.M, Barnes-Holmes D, Stewart I. Matching derived functionally-same stimulus relations: Equivalence-equivalence and classical analogies. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:255–273. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Verbal behavior by B. F. Skinner. [Review]. Language. 1959;35:26–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu E. Lições de lingüística geral. Rio de Janeiro: Ao Livro Técnico; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu E. Linguistic competence: What is it really? The Modern Language Review. 1985;80((4)):xxv–xxxv. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu E. Competencia lingüística. Madrid: Gredos; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu E. L'homme et son langage. Sterling, VA: Peeters; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal D. A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (5th ed.) Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davies A.M. Analogy, segmentation and the early neogrammarians. Transactions of the Philological Society. 1978:36–60. [Google Scholar]

- Davies A.M. Karl Brugmann and late nineteenth-century linguistics. In: Bynon T, Palmer F.R, editors. Studies in the history of western linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1986. pp. 150–171. [Google Scholar]

- De Saussure F. Notes inédites de F. de Saussure. Cahiers Ferdinand de Saussure. 1954;12:49–71. (Original work published 1891) [Google Scholar]

- Donahoe J.W, Palmer D.C. Learning and complex behavior. Richmond, MA: Ledgetop; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira J. El cambio analógico. Madrid: Gredos; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Lanza R.P, Skinner B.F. Symbolic communication between two pigeons (Columba livia domestica). Science. 1980;207:543–545. doi: 10.1126/science.207.4430.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esper E.A. Analogy and association in linguistics and psychology. Athens: University of Georgia Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Falk J.S. Otto Jespersen, Leonard Bloomfield, and American structural linguistics. Language. 1992;68:465–491. [Google Scholar]

- Fields L, Verhave T, Fath S. Stimulus equivalence and transitive associations: A methodological analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1984;42:143–157. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksberg S, Cohen J.A. Acquisition of form-class membership by syntactic position: Paradigmatic associations to nonsense syllables. Psychonomic Science. 1965;2:313–314. [Google Scholar]

- Green G, Sigurdardottir Z.G, Saunders R.R. The role of instructions in the transfer of ordinal functions through equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;55:287–304. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess D, Sailor W, Rutherford G, Baer D.M. An experimental analysis of linguistic development: The productive use of the plural morpheme. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:297–306. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C, Blackledge J.T, Barnes-Holmes D. Language and cognition: Constructing an alternative approach within the behavioral tradition. In: Hayes S.C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. pp. 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez E, Hanley G.P, Ingvarsson E.T, Tiger J.H. A preliminary evaluation of the emergence of novel mand forms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:137–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.96-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigswald H.M. The annus mirabilis 1876 and posterity. Transactions of the Philological Society. 1978;1978:17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hovdhaugen E. Foundations of western linguistics: From the beginning to the end of the first millennium A.D. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J. Transitional organization: Association techniques. In: Osgood C.E, Sebeok T.A, editors. Psycholinguistics. Baltimore: Waverly; 1954. pp. 112–118. Indiana University Publications in Anthropology and Linguistics. Memoir 10 of the International Journal of American Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J. A study of mediated association. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J. Mediated associations: Paradigms and situations. In: Cofer C.N, Musgrave B.S, editors. Verbal behavior and learning: Problems and processes. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1963. pp. 210–245. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J. A mediational account of grammatical phenomena. Journal of Communication. 1964;14:86–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1964.tb02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J. Mediation theory and grammatical behavior. In: Rosenberg S, editor. Directions in psycholinguistics. New York: Macmillan; 1965. pp. 66–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J, Newmark L.D. An experimental analogue for studying language learning. In: Osgood C.E, Sebeok T.A, editors. Psycholinguistics. Baltimore: Waverly; 1954. pp. 135–139. Indiana University Publications in Anthropology and Linguistics. Memoir 10 of the International Journal of American Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J.J, Palermo D.S. Mediation processes and the acquisition of linguistic structure. In: Bellugi U, Brown R, editors. The acquisition of language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1964. pp. 141–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen O. Language. New York: Holt; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J.E, Love N, Taylor T.J. Landmarks in linguistic thought: Vol. 2. The western tradition in the twentieth century. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner E.F.K. Hermann Paul and synchronic linguistics. Lingua. 1972;29:274–307. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner E.F.K. Paul, Hermann (1846–1921). In: Asher R.E, Simpson J.M.Y, editors. The encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford, UK: Pergamon; 1994. (Vol. 6, pp. 2992–2993). [Google Scholar]

- Lazar R. Extending sequence-class membership with matching to sample. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1977;27:381–392. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar R.M, Kotlarchyk B.J. Second-order control of sequence-class equivalences in children. Behavioural Processes. 1986;13:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(86)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V.L. Some notes on the subject matter of Skinner's Verbal Behavior. Behaviorism. 1984;12:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Malmkjær K. History of grammar. In: Malmkjær K, editor. The linguistics encyclopedia. New York: Routledge; 2002. (2nd ed., pp. 247–263). [Google Scholar]

- Malott R.W. Behavior analysis and linguistic productivity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:11–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03392978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr M.J. The stitching and the unstitching: What can behavior analysis have to say about creativity? The Behavior Analyst. 2003;26:15–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03392065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M.A, Passos M.L.R.F. Linguistic sources of Skinner's Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:89–107. doi: 10.1007/BF03392119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlvane W.J, Matos M.A, Avanzi A.L, McIlvane W.J. Maria Amelia Matos: A remembrance and appreciation. Rudimentary reading repertoires via stimulus equivalence and recombination of minimal verbal units. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22:3–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03393023. In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J, Malott R.W. Michael and Malott's dialogue on linguistic productivity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2003;19:115–118. doi: 10.1007/BF03392985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer F. Grammar (2nd ed.) Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F. Bloomfield and Skinner: Speech-community, functions of language, and scientific activity. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;1/2:76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F, Matos M.A. The influence of Bloomfield's “Language” (1933) on B. F. Skinner's “Verbal Behavior” (1957) 1998. Nov, Paper presented at the fourth International Congress on Behaviorism and the Sciences of Behavior, Seville, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Passos M.L.R.F, Matos M.A. The influence of Bloomfield's linguistics on Skinner. The Behavior Analyst. 2007;30:133–151. doi: 10.1007/BF03392151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul H. Principles of the history of language (H. A. Strong, Trans.) New York: Macmillan; 1889. (Original work published 1886) [Google Scholar]

- Peabody B. The winged word. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Percival W.K. Introduction. In: Strong H.A, Logeman W.S, Wheeler B.I, editors. Introduction to the study of the history of language. New York: AMS; 1973. (Original work published 1891) [Google Scholar]

- Place U.T. A response to Sundberg and Michael. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1985;3:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF03392808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins R.H. The neogrammarians and their nineteenth-century predecessors. Transactions of the Philological Society. 1978;76:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Robins R.H. A short history of linguistics (4th ed.) London: Longman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Koplin J.H. Introduction to psycholinguistics. In: Rosenberg S, editor. Directions in psycholinguistics. New York: Macmillan; 1965. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Saporta S. Linguistic structure as a factor and as a measure in word association. In: Jenkins J.J, editor. Associative processes in verbal behavior: A report of the Minnesota conference. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 1959. pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker J, Sherman J.A. Training generative verb usage by imitation and reinforcement procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1970;3:273–287. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1970.3-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Equivalence relations and behavior: A research story. Boston: Authors Cooperative; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir Z.G, Green G, Saunders R.R. Equivalence classes generated by sequence training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1990;53:47–63. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1990.53-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Science and human behavior. New York: Macmillan; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Contingencies of reinforcement: A theoretical analysis. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Particulars of my life. New York: Knopf; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. The shaping of a behaviorist. New York: Knopf; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Upon further reflection. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D. Relational frame theory and analogical reasoning: Empirical investigations. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2004;4:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. A functional-analytic model of analogy using the relational evaluation procedure. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart I, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, Smeets P.M. Generating derived relational networks via the abstraction of common physical properties: A possible model of analogical reasoning. The Psychological Record. 2001;51:381–408. [Google Scholar]

- Strong H.A, Logeman W.S, Wheeler B.I. Introduction to the study of the history of language. New York: AMS; 1973. (Original work published 1891) [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M.L, Michael J. A response to U. T. Place. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1983;2:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.J. Classical linguistics: An overview. In: Koerner E.F.K, Asher R.E, editors. Concise history of the language sciences: From the Sumerians to the cognitivists. New York: Pergamon; 1995. pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tomanari G.Y. We lost a leader: Maria Amelia Matos (1939–2005). The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Urcuioli P.J. Equivalence relations and behavior: A research story by Murray Sidman [Review]. Contemporary Psychology. 1996;41:280–282. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas E.A, Skinner B.F. Verbal behavior. Cambridge, MA: Prentice Hall; 1992. Introduction II. pp. xiii–xxv. (Original work published 1957) [Google Scholar]

- Vincent N. Analogy reconsidered. In: Anderson J.M, Jones C, editors. Historical linguistics II. Amsterdam: North Holland; New York: American Elsevier; 1974. pp. 427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler A.J, Sulzer B. Operant training and generalization of a verbal response form in a speech-deficient child. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1970;3:139–147. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1970.3-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler B.I, Paul H. Principles of the history of language. New York: Macmillan; 1889. Preface. pp. iii–vii. (H. A. Strong, Trans.). (Original work published 1886) [Google Scholar]

- Wulfert E, Hayes S.C. Transfer of a conditional ordering response through conditional equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1988;50:125–144. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]